1. Early Life and Background

Abbas Kiarostami was born in Tehran, Iran. His initial artistic pursuit was painting, which he continued throughout his teenage years. At the age of 18, he won a painting competition shortly before enrolling at the University of Tehran's Faculty of Fine Arts. There, he specialized in painting and graphic design, funding his studies by working as a traffic policeman.

1.1. Early Artistic Activities

During the 1960s, Kiarostami honed his skills as a painter, designer, and illustrator, contributing to the advertising industry. He designed posters and created approximately 150 commercials for Iranian television between 1962 and 1966. In the latter half of the decade, he diversified his artistic endeavors, beginning to design credit titles for films, including Gheysar by Masoud Kimiai, and illustrating children's books. These formative experiences in various visual and applied arts significantly shaped his multidisciplinary artistic development before he embarked on his filmmaking career.

2. Film Career

Kiarostami's film career spanned over four decades, during which he continuously evolved his unique cinematic style, gaining increasing international recognition for his innovative storytelling and profound thematic explorations.

2.1. 1970s

Kiarostami entered the film industry in 1970, a period that marked the rise of the Iranian New Wave movement, notably with Dariush Mehrjui's film Gāv. That same year, Kiarostami played a pivotal role in establishing the filmmaking department at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) in Tehran. He subsequently led this department for five years, laying the groundwork for his cinematic journey. Kanun quickly became one of Iran's most distinguished film studios, producing not only Kiarostami's early works but also acclaimed Persian films such as The Runner and Bashu, the Little Stranger.

Kiarostami's directorial debut, produced by Kanun, was the 12-minute neo-realistic short film The Bread and Alley (1970), which depicted a schoolboy's tense encounter with an aggressive dog. He later described its production as a very challenging experience due to working with a young child, a dog, and an unprofessional crew, particularly clashing with the cinematographer over his unconventional preference for capturing entire scenes in single, unbroken shots to maintain rhythm and content. This individualistic approach to filmmaking became a hallmark of his style.

Following Breaktime (1972), Kiarostami directed The Experience (1973) and then released The Traveler (مسافرMossaferPersian) in 1974. The Traveler centers on Qassem Julayi, a troubled boy from a small Iranian city who schemes to raise money to attend a football match in Tehran, only to face an ironic twist of fate. The film explored human behavior, the balance of right and wrong, and solidified Kiarostami's reputation for realism, diegetic simplicity, and stylistic complexity, along with his growing fascination with physical and spiritual journeys.

In 1975, Kiarostami directed two short films, So Can I and Two Solutions for One Problem. He followed these with Colors in early 1976, and then the 54-minute film A Wedding Suit later that year, which told the story of three teenagers embroiled in conflict over a suit for a wedding. Kiarostami's next significant work was Report (1977), a considerably longer film at 112 minutes, focusing on a tax collector accused of bribery and exploring themes including suicide. He concluded the decade by producing and directing First Case, Second Case in 1979.

2.2. 1980s

The early 1980s saw Kiarostami directing several short films, including Toothache (1980), Orderly or Disorderly (1981), and The Chorus (1982). In 1983, he directed Fellow Citizen, a documentary film, followed by another documentary, First Graders in 1984.

It was with the release of Where Is the Friend's Home? (1987) that Kiarostami began to gain significant recognition outside Iran. This film, the first of what critics would later call the Koker trilogy, presents the simple yet profound account of a conscientious eight-year-old schoolboy determined to return his friend's notebook to a neighboring village to prevent his friend's expulsion. The film is noted for its poetic portrayal of the Iranian rural landscape and its realism, elements that became central to Kiarostami's signature style. He notably depicted the narrative from a child's perspective, emphasizing traditional Iranian rural beliefs.

The Koker trilogy consists of Where Is the Friend's Home? (1987), And Life Goes On (1992, also known as Life and Nothing More), and Through the Olive Trees (1994). These films are linked by their setting in the village of Koker in northern Iran and their thematic connection to the devastating 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake, which claimed 40,000 lives. Kiarostami masterfully uses the themes of life, death, change, and continuity to weave the films together, often representing the power of human resilience in the face of destruction. The trilogy achieved success in France and other Western European countries like the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, and Finland. However, Kiarostami himself did not originally conceive them as a trilogy, suggesting that the latter two films, along with Taste of Cherry (1997), formed a different trilogy based on their shared theme of the preciousness of life.

In 1987, Kiarostami was involved in the screenwriting and editing of The Key, though he did not direct it. He concluded the decade with the release of the documentary film Homework in 1989.

2.3. 1990s

The 1990s marked Kiarostami's international breakthrough. His first film of the decade, Close-Up (1990), is a seminal work of docufiction. It narrates the real-life trial of Hossein Sabzian, a man who impersonated filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf to con a family into believing they would star in his new film. While the family suspected theft, Sabzian argued his motives were more complex. The film, part-documentary and part-staged, delves into Sabzian's moral justification, questioning his artistic sensibilities. Close-Up garnered widespread praise from acclaimed directors like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Jean-Luc Godard, and Nanni Moretti, and was released across Europe. It was also ranked among the 50 greatest films of all time in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll and No. 42 in the British Film Institute's The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time.

In 1992, Kiarostami directed Life, and Nothing More... (also known as And Life Goes On), which critics regarded as the second film of the Koker trilogy. The film follows a father and his young son as they journey from Tehran to Koker in search of two boys they fear may have died in the 1990 earthquake. As they travel through the devastated landscape, they encounter survivors striving to continue with their lives amidst the disaster. For his direction of this film, Kiarostami received the Prix Roberto Rossellini, his first professional film award.

The final film of the Koker trilogy was Through the Olive Trees (1994), which expands a peripheral scene from Life and Nothing More into its central drama. Critics like Adrian Martin characterized the filmmaking style of the Koker trilogy as "diagrammatical," connecting the zig-zagging patterns in the landscape with the geometry of life's forces. A flashback to the zig-zag path in Life and Nothing More... symbolically links to the post-earthquake reconstruction depicted in Through the Olive Trees. In 1995, Miramax Films distributed Through the Olive Trees in US theaters.

Kiarostami also contributed his screenwriting talents during this decade, writing The Journey and The White Balloon (1995) for his former assistant, Jafar Panahi. Between 1995 and 1996, he participated in Lumière and Company, a collaborative project with 40 other film directors.

A major milestone in his career came in 1997 when Kiarostami won the prestigious Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival for his film Taste of Cherry. This drama depicts a man, Mr. Badii, determined to commit suicide, exploring profound themes such as morality, the legitimacy of suicide, and the meaning of compassion.

Kiarostami concluded the 1990s with The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), which earned the Grand Jury Prize (Silver Lion) at the Venice International Film Festival. The film subtly contrasts rural and urban perspectives on the dignity of labor, and addresses themes of gender equality and the benefits of progress, through the sojourn of a stranger in a remote Kurdish village. A distinctive feature of this movie is that many characters are heard but never seen, with at least thirteen to fourteen speaking characters remaining off-screen.

2.4. 2000s

In 2000, at the San Francisco Film Festival award ceremony, Kiarostami was honored with the Akira Kurosawa Prize for lifetime achievement in directing. In a surprising gesture, he presented the award to veteran Iranian actor Behrooz Vossoughi in recognition of his contributions to Iranian cinema.

In 2001, Kiarostami and his assistant, Seifollah Samadian, traveled to Kampala, Uganda, at the request of the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development. Their initial purpose was research for a documentary on programs assisting Ugandan orphans, but Kiarostami ultimately edited the entire film, ABC Africa, from the video footage shot during their ten-day trip. The film highlighted the high number of orphans in Uganda, largely due to the AIDS epidemic. Geoff Andrew, editor for Time Out, noted that "Like his previous four features, this film is not about death but life-and-death: how they're linked, and what attitude we might adopt with regard to their symbiotic inevitability."

The following year, Kiarostami directed Ten, a film notable for its unusual method of filmmaking, which largely abandoned conventional scriptwriting. Kiarostami was not physically present during the filming, which took place in a moving automobile. He provided suggestions to the actors, and a camera mounted on the dashboard recorded them as they drove through Tehran over several days. The film consists of ten conversations between a woman driving and her various passengers, including her sister, a hitchhiking prostitute, and her demanding young son. This innovative approach, utilizing digital cameras to virtually eliminate the director's physical presence, was praised by many critics. A. O. Scott of The New York Times lauded Kiarostami as a "master of automotive cinema," recognizing his understanding of the automobile as a space for reflection, observation, and conversation.

In 2003, Kiarostami directed Five (also known as Five Dedicated to Ozu in Japanese sources, reflecting Kiarostami's admiration for Ozu Yasujiro), a poetic feature devoid of dialogue or characterization. It comprises five single-take long shots of nature along the shores of the Caspian Sea, filmed with a hand-held DV camera. Despite the absence of a clear narrative, Andrew described the film as "more than just pretty pictures," suggesting it forms an "abstract or emotional narrative arc" moving from separation to community, motion to rest, and silence to sound, ending on a note of rebirth. He highlighted the hidden artistry behind the apparent simplicity of its imagery. Kiarostami also wrote the screenplay for Crimson Gold (2003) and directed the documentary 10 on Ten (2004), which further explored his filmmaking methods, especially those used in Ten.

In 2005, Kiarostami contributed the central segment to Tickets, a portmanteau film set on a train traversing Italy, with other segments directed by Ken Loach and Ermanno Olmi.

His 2008 feature, Shirin, features close-up shots of many notable Iranian actresses and the French actress Juliette Binoche as they watch a film based on the partly mythological Persian romance tale of Khosrow and Shirin. The film explores themes of female self-sacrifice and has been described as a compelling examination of the relationship between image, sound, and female spectatorship.

That summer, Kiarostami directed Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera Così fan tutte, conducted by Christophe Rousset, at the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence with William Shimell in the cast. However, he was unable to direct the following year's performances at the English National Opera due to a refusal of permission to travel abroad.

2.5. 2010s

The 2010s saw Kiarostami venture beyond Iran for his film productions. His 2010 film, Certified Copy, starring Juliette Binoche, was shot in Tuscany, Italy, marking his first film made outside his home country. The story, focusing on an encounter between a British man and a French woman, was entered in competition for the Palme d'Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. Critics offered mixed reviews: while Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian found it an "intriguing oddity" that was "baffling, contrived, and often simply bizarre," Roger Ebert praised Kiarostami's "brilliant" ability to create offscreen spaces. Binoche won the Best Actress Award at Cannes for her performance.

Kiarostami's penultimate film, Like Someone in Love (2012), was set and filmed in Japan and received largely positive critical reviews.

His final film, the experimental 24 Frames, based on 24 of Kiarostami's still photographs, was released posthumously in 2017. It enjoyed a highly positive critical reception, achieving a 92% score on Rotten Tomatoes.

2.6. Film Festival Work

Kiarostami was a frequent and respected presence at international film festivals, serving as a jury member on numerous occasions. He was notably a jury member at the Cannes Film Festival in 1993, 2002, and 2005. In 2005, he presided over the Caméra d'Or Jury at Cannes, and in 2014, he was announced as the president of the Cinéfondation and short film sections of the festival.

His other jury commitments included the Venice Film Festival in 1985, the Locarno International Film Festival in 1990, the San Sebastian International Film Festival in 1996, the São Paulo International Film Festival in 2004, and the Capalbio Cinema Festival in 2007, where he served as jury president. In 2011, he was a jury member at the Küstendorf Film and Music Festival. Additionally, Kiarostami made regular appearances at many other film festivals across Europe, such as the Estoril Film Festival in Portugal. In 2005, he headed the jury for the 10th Busan International Film Festival.

3. Cinematic Style and Themes

Abbas Kiarostami's filmmaking is defined by a unique and highly individualistic style, characterized by unconventional techniques, a profound engagement with philosophical questions, and a deep connection to poetry and imagery.

3.1. Unique Cinematic Techniques

Despite comparisons to directors like Satyajit Ray, Vittorio De Sica, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Tati, Kiarostami's films exhibit a singular style, often employing techniques of his own invention. His early work already showed this inclination; during the filming of The Bread and Alley in 1970, he insisted on capturing entire scenes in single, flowing shots, rather than breaking them into separate takes, believing this approach would create a more profound tension and maintain the film's inherent rhythm.

Unlike many directors, Kiarostami had little interest in staging extravagant combat or complicated chase scenes in large-scale productions. Instead, he sought to mold the medium of film to his unique specifications. His signature style became more apparent with the Koker trilogy, which included numerous self-references to his own film material, connecting common themes and subject matter across the films. Film critic Stephen Bransford noted that Kiarostami's films do not typically reference the works of other directors but are instead self-referential, often engaging in an ongoing dialectic where one film reflects on and partially demystifies an earlier one.

Kiarostami continuously experimented with new modes of filming, employing diverse directorial methods and techniques. A notable example is Ten (2002), which was filmed entirely within a moving automobile, with Kiarostami himself not physically present. He provided general suggestions to the actors, and a camera positioned on the dashboard captured their faces in a series of extreme close-ups as they drove around Tehran. This digital micro-cinema approach, characterized by micro-budget filmmaking and digital production, virtually eliminated the director's direct physical presence during shooting.

According to film professors like Jamsheed Akrami, Kiarostami consistently aimed to redefine film by increasing audience involvement. In his later years, he also progressively trimmed the timespan within his films, reducing filmmaking from a collective endeavor to a purer, more basic form of artistic expression. His films often feature docufiction, child protagonists, narratives set in rural villages, and conversations unfolding inside cars using stationary cameras. His camera placement often defied standard audience expectations; in the closing sequences of Life and Nothing More and Through the Olive Trees, the audience is compelled to imagine the dialogue and circumstances of important scenes. In Homework and Close-Up, parts of the soundtrack are intentionally masked or silenced. This subtlety often makes Kiarostami's cinematic expression resistant to conventional critical analysis.

3.2. Poetry and Imagery

Kiarostami's cinematic style is deeply intertwined with Persian literature, particularly poetry. Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak observed that a key aspect of Kiarostami's art was his ability to capture the essence of Persian poetry and translate it into poetic imagery within his filmic landscapes. Several of his movies, such as Where Is the Friend's Home? and The Wind Will Carry Us, directly quote classical Persian poetry, underscoring the intimate artistic link and connection between literature and cinema. This interweaving of poetry also reflects on the connection between the past and present, and between continuity and change.

Characters in his films often recite poems from classical Persian poets like Omar Khayyám or modern Persian poets such as Sohrab Sepehri and Forough Farrokhzad. For instance, a scene in The Wind Will Carry Us features a long shot of a wheat field with rippling golden crops, through which a doctor and a filmmaker ride a scooter on a winding road. In response to a comment about the other world being better, the doctor recites a poem by Khayyam:

:They promise of houries in heaven

:But I would say wine is better

:Take the present to the promises

:A drum sounds melodious from distance

Sima Daad argued that Kiarostami's adaptation of poems by Sohrab Sepehri and Forough Farrokhzad extends the domain of textual transformation, moving beyond inter-textual potential to a trans-generic potential in the realm of adaptation theory. Kiarostami's own poetry is reminiscent of Sohrab Sepehri's later nature poems, characterized by succinct allusions to philosophical truths, a non-judgmental tone, and a structure that often omits personal pronouns, adverbs, or excessive adjectives, often possessing a haiku-esque quality with the inclusion of a kigo (season word).

3.3. Themes of Life and Death

The concepts of change and continuity, alongside the fundamental themes of life and death, play a major and recurring role throughout Kiarostami's works. These themes are central to the Koker trilogy, particularly in the aftermath of the 1990 Manjil-Rudbar earthquake disaster, where they highlight the power of human resilience to overcome and defy destruction, and the human instinct for survival.

In contrast to the survival instinct conveyed in the Koker films, Taste of Cherry (1997) delves into the fragility and preciousness of life, focusing on the meaning and legitimacy of suicide. Some film critics suggest that the interplay of light and dark scenes in Kiarostami's cinematic grammar, as seen in films like Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us, implies the mutual existence of life with its endless possibilities and death as an undeniable aspect of human existence.

3.4. Spirituality

Kiarostami's complex sound-images and philosophical approach have often led to comparisons with "mystical" filmmakers such as Andrei Tarkovsky and Robert Bresson. Many Western critics interpret his films as spiritual, positioning him as the Iranian equivalent of these contemplative directors due to a similarly austere, "spiritual" poetics and moral commitment. Some scholars even draw parallels between certain imageries in Kiarostami's films and concepts found in Sufi mysticism.

However, there is critical debate on the extent of spirituality in his works. While figures like David Sterritt and Alberto Elena emphasize the spiritual interpretations, other critics, including David Walsh and Hamish Ford, have rated the influence of spirituality in his films as lower.

The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, in discussing Kiarostami's work (especially Life and Nothing More...), argued that his films are neither purely fiction nor purely documentary, but rather "evidence." Nancy asserted that Kiarostami's cinema goes beyond mere representation or reportage, instead inventing and constructing images that serve as "evidence" of existence itself. For Nancy, this concept of cinema as "evidence" is intrinsically linked to Kiarostami's exploration of life-and-death, not as opposing forces, but as inextricably connected elements. He suggests that Kiarostami's films illustrate how "existence" extends beyond simple biological life, incorporating an irreducibly fictive element, and thus becoming "contaminated by mortality." This philosophical viewpoint provides a key to understanding Kiarostami's enigmatic statement that "We can never get close to the truth except through lying."

4. Artistic Versatility

Kiarostami was a truly multifaceted artist whose creative expression extended far beyond filmmaking, encompassing a wide range of artistic disciplines. He belonged to a rare group of filmmakers, alongside figures such as Jean Cocteau, Satyajit Ray, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Derek Jarman, and Alejandro Jodorowsky, who also excelled in other genres to express their interpretation of the world and human identity.

4.1. Photography and Poetry

Kiarostami was highly regarded as both a photographer and a poet. His photographic work includes Untitled Photographs, a collection of over thirty images, primarily snow landscapes taken in his hometown of Tehran between 1978 and 2003, which were also exhibited internationally.

As a poet, he published a collection of his poems in 1999. A bilingual collection of more than 200 of his poems, titled Walking with the Wind, was published by Harvard University Press. Riccardo Zipoli studied the interconnections between Kiarostami's poems and films, finding similarities in their treatment of "uncertain reality." His poetry is often compared to the later nature poems of the Persian painter-poet Sohrab Sepehri, characterized by its succinct allusions to philosophical truths, a non-judgmental poetic voice, and a structure that frequently lacks personal pronouns, adverbs, or an over-reliance on adjectives, often taking on a haiku-esque quality with the inclusion of a kigo (season word). In 2015, three volumes of his original verse, along with his selections from classical and contemporary Persian poets including Nima, Hafez, Rumi, and Saadi, were translated into English and published in bilingual (Persian/English) editions by Sticking Place Books in New York.

4.2. Other Artistic Pursuits

Beyond cinema, photography, and poetry, Kiarostami explored other artistic domains. In 2003, he directed Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera Così fan tutte, which premiered at the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence and was later performed at the English National Opera in London in 2004. He also engaged with installation art, demonstrating the breadth of his creative expression across various visual and performing arts.

5. Personal Life

In 1969, Abbas Kiarostami married Parvin Amir-Gholi, with whom he had two sons, Ahmad and Bahman. The couple divorced in 1982.

Kiarostami notably chose to remain in Iran after the 1979 revolution, a period when many of his peers emigrated from the country. He regarded this decision as one of the most crucial in his career, believing that his continued presence in Iran and his strong national identity were fundamental to his development as a filmmaker. He famously articulated this belief using a natural metaphor: "When you take a tree that is rooted in the ground and transfer it from one place to another, the tree will no longer bear fruit. And if it does, the fruit will not be as good as it was in its original place. This is a rule of nature. I think if I had left my country, I would be the same as the tree."

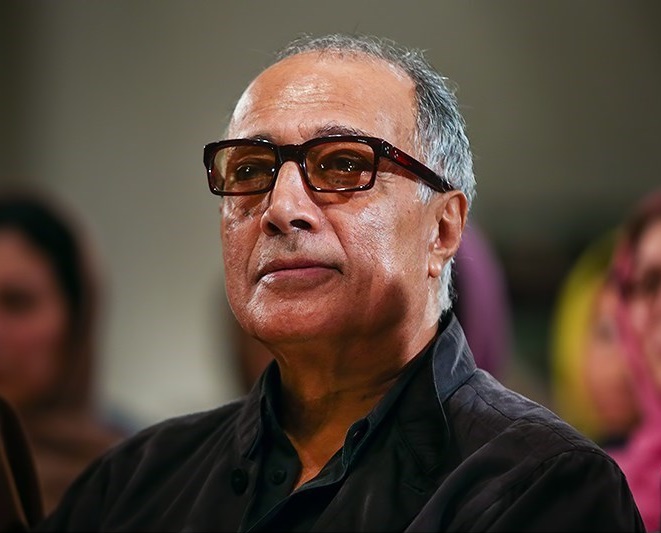

Throughout his life, Kiarostami was frequently seen wearing dark spectacles or sunglasses, which he needed due to a sensitivity to light.

6. Illness and Death

The final period of Kiarostami's life was marked by health struggles that ultimately led to his passing, prompting widespread mourning and reflections on his legacy.

6.1. Circumstances of Death

In March 2016, Abbas Kiarostami was hospitalized for intestinal bleeding and reportedly fell into a coma after undergoing two operations. Initial reports from sources, including a spokesman for the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education, indicated he was suffering from gastrointestinal cancer. However, on April 3, 2016, Reza Paydar, the director of Kiarostami's medical team, issued a statement denying that the filmmaker had cancer. Despite this, in late June, Kiarostami traveled from Iran to Paris for further medical treatment, where he died on July 4, 2016, at the age of 76. The week before his death, he had been invited to join the Academy Awards in Hollywood as part of efforts to diversify its Oscar judges.

Following his death, Iran's ambassador to France, Ali Ahani, initially stated that Kiarostami's body would be transferred to Iran for burial at Behesht-e Zahra cemetery. However, it was later announced that, according to his will, his body would be buried in Lavasan, a resort town approximately 25 mile (40 km) northeast of Tehran. His body was repatriated to Tehran's Imam Khomeini International Airport on July 8, 2016, where a crowd of Iranian film directors, actors, actresses, and other artists gathered to pay their respects.

Controversy arose regarding the medical care he received. On June 8, 2016, fellow filmmaker and close friend Mohammad Shirvani quoted Kiarostami on his Facebook page, stating, "I do not believe I could stand and direct any more films. They [the medical team] destroyed it [his digestive system]." This comment sparked a campaign among Iranians on social media platforms to investigate the possibility of medical error. However, Kiarostami's eldest son, Ahmad Kiarostami, initially denied any medical error and stated that his father's health was not a cause for alarm. Following Kiarostami's death, Dr. Alireza Zali, Head of the Iranian Medical Council, sent a letter to his French counterpart, Patrick Bouet, requesting Kiarostami's medical file for further investigation. Nine days after his death, on July 13, 2016, his family formally filed a complaint of medical maltreatment through Kiarostami's personal doctor. Dariush Mehrjui, another renowned Iranian cinema director, also criticized the medical team and demanded legal action.

6.2. Funeral and Mourning

The death of Abbas Kiarostami elicited a powerful wave of tributes and mourning from the international film community, public figures, and the Iranian populace. Martin Scorsese expressed that he was "deeply shocked and saddened" by the news, describing Kiarostami as "one of our great artists." Oscar-winning Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi, who had planned to visit Kiarostami in Paris, conveyed his profound sadness and shock. Mohsen Makhmalbaf acknowledged Kiarostami's immense contribution, stating that Iran's cinema owed its global reputation to him, adding that Kiarostami "changed the world's cinema; he freshened it and humanized it in contrast with Hollywood's rough version." Esin Celebi, the 22nd niece of Persian mystic and poet Jalal al-Din Rumi, also extended her condolences. UNESCO's Iranian representative office opened a memorial book for signatures to honor Kiarostami.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani remarked on Twitter that the director's "different and profound attitude towards life and his invitation to peace and friendship" would stand as a "lasting achievement." Foreign Minister Mohammad-Javad Zarif also noted that Kiarostami's death was a significant loss for international cinema. French President François Hollande praised Kiarostami for fostering "close artistic ties and deep friendships" with France. Major international media outlets, including The New York Times, CNN, The Guardian, The Huffington Post, The Independent, Associated Press, Euronews, and Le Monde, all reported on his passing and paid tribute to his legacy. The New York Times headlined: "Abbas Kiarostami, Acclaimed Iranian Filmmaker, Dies at 76," and Peter Bradshaw lauded him as "a sophisticated, self-possessed master of cinematic poetry." In Paris, a vigil was held by the River Seine, where mourners allowed photos of Kiarostami to float away on the water, a symbolic farewell.

On July 10, six days after his death, a large and emotional funeral ceremony took place in Tehran. Artists, cultural authorities, government officials, and the general public gathered at the Center for the Intellectual Education of Children, the very place where Kiarostami had begun his filmmaking journey four decades prior. Attendees held banners adorned with film titles and posters, praising his contributions to Iranian culture and cinema. The ceremony was hosted by renowned Iranian actor Parviz Parastooie and featured speeches by painter Aidin Aghdashlou and prize-winning film director Asghar Farhadi, both emphasizing Kiarostami's professional abilities and impact. Following the public ceremony, Kiarostami was laid to rest in a private ceremony in the northern Tehran town of Lavasan, according to his personal will.

7. Reception and Criticism

Abbas Kiarostami's work garnered extensive worldwide acclaim from audiences and critics alike, establishing him as a master filmmaker, though his unconventional style also sparked critical discussion and occasional controversies.

7.1. Critical Acclaim and Recognition

Kiarostami received widespread praise and recognition, and in 1999, he was voted the most important Iranian film director of the 1990s in two international critics' polls. Four of his films were ranked among the top six in Cinematheque Ontario's "Best of the '90s" poll. He earned recognition from prominent film theorists, critics, and peers, including Jean-Luc Godard, Nanni Moretti, and Chris Marker.

Akira Kurosawa famously stated about Kiarostami's films: "Words cannot describe my feelings about them... When Satyajit Ray passed on, I was very depressed. But after seeing Kiarostami's films, I thanked God for giving us just the right person to take his place." Martin Scorsese lauded Kiarostami, commenting that he "represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema." Austrian director Michael Haneke regarded Kiarostami's work as among the best of any living director. In 2006, a panel of critics for The Guardian ranked Kiarostami as the best contemporary non-American film director.

The London Film School organized a workshop and festival of his work in 2005, titled "Abbas Kiarostami: Visions of the Artist," with the director of the school, Ben Gibson, noting Kiarostami's unique clarity to "invent cinema from its most basic elements." He was later made an Honorary Associate of the school. In 2007, the Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1 in New York co-organized a festival of Kiarostami's work titled Abbas Kiarostami: Image Maker.

Kiarostami's unique cinematic style and influence have been the subject of several books and three films: Opening Day of Close-Up (1996), directed by Nanni Moretti; Abbas Kiarostami: The Art of Living (2003), directed by Pat Collins and Fergus Daly; and Abbas Kiarostami: A Report (2014), directed by Bahman Maghsoudlou. He also served as a member of the advisory board of the World Cinema Foundation, founded by Martin Scorsese, which aims to find and reconstruct neglected world cinema films. Kiarostami openly expressed his admiration for Ozu Yasujiro, even dedicating his 2003 film Five to the Japanese master.

7.2. Awards and Honors

Abbas Kiarostami accumulated at least seventy awards by the year 2000, underscoring his profound impact on global cinema. His notable accolades include:

- Prix Roberto Rossellini (1992)

- Prix Cine Decouvertes (1992)

- François Truffaut Award (1993)

- Pier Paolo Pasolini Award (1995)

- UNESCO Federico Fellini Gold Medal (1997)

- Palme d'Or, Cannes Film Festival for Taste of Cherry (1997)

- Honorary Golden Alexander Prize, Thessaloniki International Film Festival (1999)

- Silver Lion, Venice Film Festival for The Wind Will Carry Us (1999)

- Akira Kurosawa Award (2000)

- Honorary doctorate, École Normale Supérieure (2003)

- Konrad Wolf Prize (2003)

- President of the Jury for Caméra d'Or Award, Cannes Film Festival (2005)

- Fellowship of the British Film Institute (2005)

- Gold Leopard of Honor, Locarno International Film Festival (2005)

- Prix Henri-Langlois Prize (2006)

- Honorary doctorate, University of Toulouse (2007)

- World's Great Masters award, Kolkata International Film Festival (2007)

- Glory to the Filmmaker Award, Venice Film Festival (2008)

- Honorary doctorate, University of Paris (2010)

- Lifetime Achievement Award for Contribution to World Cinematography (BIAFF - Batumi International Art-house Film Festival, 2010)

- Japan's Medal of Honor (2013)

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (2014)

- Honorary Golden Orange Prize, International Antalya Film Festival (2014)

He also received specific film awards such as the Director's Award at the Singapore International Film Festival for Through the Olive Trees (1995), the Un Certain Regard award at Cannes, and Juliette Binoche's Best Actress Award at Cannes for her performance in Certified Copy, which Kiarostami directed.

7.3. Criticisms and Controversies

While Kiarostami earned significant acclaim, his unconventional cinematic style also led to criticism and, at times, controversy. Critics such as Jonathan Rosenbaum observed that Kiarostami's films tended to "divide audiences"-in Iran, in the US, and globally. This division often stemmed from his deliberate omission of what Hollywood cinema typically considers "essential narrative information." For instance, in the concluding sequences of Life and Nothing More and Through the Olive Trees, audiences are compelled to imagine crucial dialogue and circumstances. Similarly, in Homework and Close-Up, portions of the soundtrack are masked or silenced, further challenging conventional viewing expectations. Critics have suggested that the subtlety of Kiarostami's cinematic expression often resists straightforward critical analysis.

Kiarostami faced notable challenges from the Iranian government. He reported that the government had refused to permit the screening of his films for a decade, to which he responded, "I think they don't understand my films and so prevent them being shown just in case there is a message they don't want to get out."

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Kiarostami was denied a visa to attend the New York Film Festival in 2002, despite invitations from the festival, Ohio University, and Harvard University. The festival director, Richard Peña, publicly criticized the decision, stating it sent a "terrible negative signal... to the entire Muslim world." In protest, Finnish film director Aki Kaurismäki boycotted the festival.

More recently, in August 2020, Mania Akbari, an actress who starred in Kiarostami's film Ten, accused him of plagiarism, alleging that he edited private footage shot by her into the film without her permission. Akbari's daughter, Amina Maher, who also appeared in Ten, stated in her 2019 short film Letter to My Mother that her scenes in Ten were filmed without her knowledge. Akbari and Maher have since requested the film's distributor, MK2, to halt its circulation, and in response, the British Film Institute removed Ten from a Kiarostami retrospective. In 2022, Akbari further accused Kiarostami of sexually assaulting her twice: once in Tehran when she was 25 and he was approximately 60, and again in London after Ten had premiered.

8. Influence

Abbas Kiarostami's impact on cinema is profound and far-reaching, significantly shaping both Iranian cinema and the broader landscape of global filmmaking, while serving as a lasting inspiration for new generations of artists and thinkers. As a key figure in the Iranian New Wave, which emerged in the late 1960s, Kiarostami, along with pioneers like Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Shahid Saless, Bahram Beizai, and Parviz Kimiavi, developed a movement characterized by poetic dialogue and allegorical storytelling that delved into political and philosophical issues.

His unique approach, often described as a "singular style" despite comparisons to directors such as Satyajit Ray, Vittorio De Sica, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Tati, redefined what a film could be. As Mohsen Makhmalbaf articulated, Kiarostami "changed the world's cinema; he freshened it and humanized it in contrast with Hollywood's rough version." This humanizing effect, coupled with his innovative techniques and profound thematic explorations, cemented his status as a master of cinematic poetry and ensured his enduring legacy as an inspirational figure for subsequent filmmakers and audiences worldwide.

9. Filmography

9.1. Feature Films

| Year | Film | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | The Experience | Written with Amir Naderi |

| 1974 | The Traveler | |

| 1976 | A Wedding Suit | Written with Parviz Davayi |

| 1977 | The Report | |

| 1979 | First Case, Second Case | |

| 1983 | Fellow Citizen | Documentary film |

| 1984 | First Graders | Documentary film |

| 1987 | Where Is the Friend's Home? | First film of the Koker trilogy |

| 1987 | The Key | Screenwriter and editor only |

| 1989 | Homework | Documentary film |

| 1990 | Close-Up | Docufiction film |

| 1992 | Life, and Nothing More... | Second film of the Koker trilogy; alternatively titled And Life Goes On |

| 1994 | Through the Olive Trees | Third and final film of the Koker trilogy |

| 1994 | Safar | Alternatively titled The Journey |

| 1995 | The White Balloon | Screenwriter only |

| 1997 | Taste of Cherry | |

| 1999 | Willow and Wind | Screenwriter only |

| 1999 | The Wind Will Carry Us | |

| 2001 | ABC Africa | Documentary film |

| 2002 | The Deserted Station | Story concept by Kiarostami; screenplay only |

| 2002 | Ten | Docufiction film |

| 2003 | Crimson Gold | Screenwriter only |

| 2003 | Five Dedicated to Ozu | Documentary film; alternatively titled Five |

| 2004 | 10 on Ten | Documentary film on Kiarostami's own films, especially Ten |

| 2005 | Tickets | Directed with Ermanno Olmi and Ken Loach; written with Ermanno Olmi and Paul Laverty |

| 2006 | Men at Work | Initial story concept by Kiarostami |

| 2006 | Víctor Erice-Abbas Kiarostami: Correspondences | Collaboration with Víctor Erice; also written and directed by Erice |

| 2007 | Persian Carpet | Directed only the Is There a Place to Approach? segment; one of 15 segments by different Iranian directors |

| 2008 | Shirin | |

| 2010 | Certified Copy | |

| 2012 | Like Someone in Love | Japanese film |

| 2012 | Meeting Leila | |

| 2016 | Final Exam | Posthumous; story concept by Kiarostami before his passing; also written by Adel Yaraghi, who directed |

| 2017 | 24 Frames | Posthumous |

9.2. Short Films

| Year | Film | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | The Bread and Alley | |

| 1972 | Recess | |

| 1975 | Two Solutions for One Problem | |

| 1975 | So Can I | |

| 1976 | The Colours | |

| 1977 | Tribute to the Teachers | Documentary |

| 1977 | Jahan-nama Palace | Documentary |

| 1977 | How to Make Use of Leisure Time | |

| 1978 | Solution | Also called Solution No.1 |

| 1980 | Driver | |

| 1980 | Orderly or Disorderly | |

| 1982 | The Chorus | |

| 1983 | Toothache | |

| 1995 | Solution | |

| 1995 | Abbas Kiarostami | Segment from Lumière and Company |

| 1997 | The Birth of Light | |

| 1999 | Volte sempre, Abbas! | |

| 2005 | Roads of Kiarostami | |

| 2007 | Is There a Place to Approach? | One of 15 segments in Persian Carpet |

| 2007 | Where is my Romeo? | Segment from To Each His Own Cinema |

| 2010 | No | Documentary |

| 2013 | The Girl in the Lemon Factory | Also written by Chiara Maranon, who directed |

| 2014 | Seagull Eggs | Documentary |

10. Books by Kiarostami

Abbas Kiarostami's literary contributions include several volumes of his own poetry and selections from classical and contemporary Persian poets, many of which have been translated into multiple languages.

- Abbas Kiarostami: Cahiers du Cinéma Livres (1997).

- La Lettre du Cinema: P.O.L. (1997).

- Walking with the Wind (Voices and Visions in Film): English translation by Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak and Michael C. Beard, Harvard Film Archive; Bilingual edition (2002).

- 10 (ten): Cahiers du Cinéma Livres (2002).

- With Nahal Tajadod and Jean-Claude Carrière Avec le vent: P.O.L. (2002).

- Le vent nous emportera: Cahiers du Cinéma Livres (2002).

- Havres: French translation by Tayebeh Hashemi and Jean-Restom Nasser, ÉRÈS (PO&PSY); Bilingual edition (2010).

- A Wolf on Watch (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2015).

- With the Wind (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2015).

- Wind and Leaf (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2015).

- Wine (poetry by Hafez) (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2015).

- Tears (poetry by Saadi) (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2015).

- Water (poetry by Nima) (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2015).

- Fire (poetry by Rumi) (four volumes) (Persian / English dual language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2016).

- Night: Poetry from the Contemporary Persian Canon (two volumes) (Persian / English Dual Language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2016).

- Night: Poetry from the Classical Persian Canon (two volumes) (Persian / English Dual Language), English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2016).

- In the Shadow of Trees: The Collected Poetry of Abbas Kiarostami, English Translation by Iman Tavassoly and Paul Cronin, Sticking Place Books (2016).

- Lessons with Kiarostami (edited by Paul Cronin), Sticking Place Books (2015).