1. Early Life and Background

Zita's early life was shaped by her noble lineage, her family's unique circumstances, and a strict, multilingual, and religiously focused upbringing that instilled in her a strong sense of duty and compassion.

1.1. Birth and Family

Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma was born on May 9, 1892, at the Villa Pianore in the Italian Province of Lucca. She was named Zita after a popular 13th-century Italian saint from Tuscany, an unusual name even at the time. She was the third daughter and fifth child of the deposed Robert I, Duke of Parma, and his second wife, Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal, a daughter of King Miguel I of Portugal and his wife Adelaide of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg. Zita's father had lost his throne as a result of the Italian unification movement in 1859 when he was still a child.

Duke Robert had a remarkably large family, fathering twelve children during his first marriage to Princess Maria Pia of the Two Sicilies, six of whom were mentally disabled, and three died young. He became a widower in 1882, and two years later married Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal. This second marriage produced a further twelve children, making Zita the 17th among Duke Robert's 24 children. The family frequently moved between Villa Pianore, a large property located between Pietrasanta and Viareggio, and his Schwarzau Castle in Lower Austria. Zita spent most of her formative years in these two residences, with the family spending most of the year in Austria, moving to Pianore in the winter and returning in the summer. To accommodate their large family and belongings, they used a special train with sixteen coaches for these journeys.

1.2. Education

Zita and her numerous siblings were raised to be multilingual, speaking Italian, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, and English. Zita recalled her upbringing as international, with her father considering himself primarily French and spending weeks each year with the elder children at Château de Chambord, his main property on the Loire River. When asked about their identity, her father replied, "We are French princes who reigned in Italy." In fact, only three of his twenty-four children, including Zita, were actually born in Italy.

At the age of ten, Zita was sent to a boarding school at Zanberg in Upper Bavaria, which maintained a strict regime of study and religious instruction. She was summoned home in the autumn of 1907 following the death of her father. Her maternal grandmother then sent Zita and her sister Francesca to a convent on the Isle of Wight to complete their education. Raised as devout Catholics, the Parma children regularly engaged in charitable work for the poor. In Schwarzau, the family converted surplus cloth into clothes, while Zita and Francesca personally distributed food, clothing, and medicines to the needy in Pianore. Three of Zita's sisters became nuns, and for a time, Zita considered following the same path. After a period of poor health, she was sent for a traditional cure at a European spa for two years, which helped her regain her health.

2. Marriage and Imperial Life

Zita's journey from a princess of a dispossessed ducal house to the Empress consort of Austria and Queen of Hungary was swift and dramatic, coinciding with the final, tumultuous years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

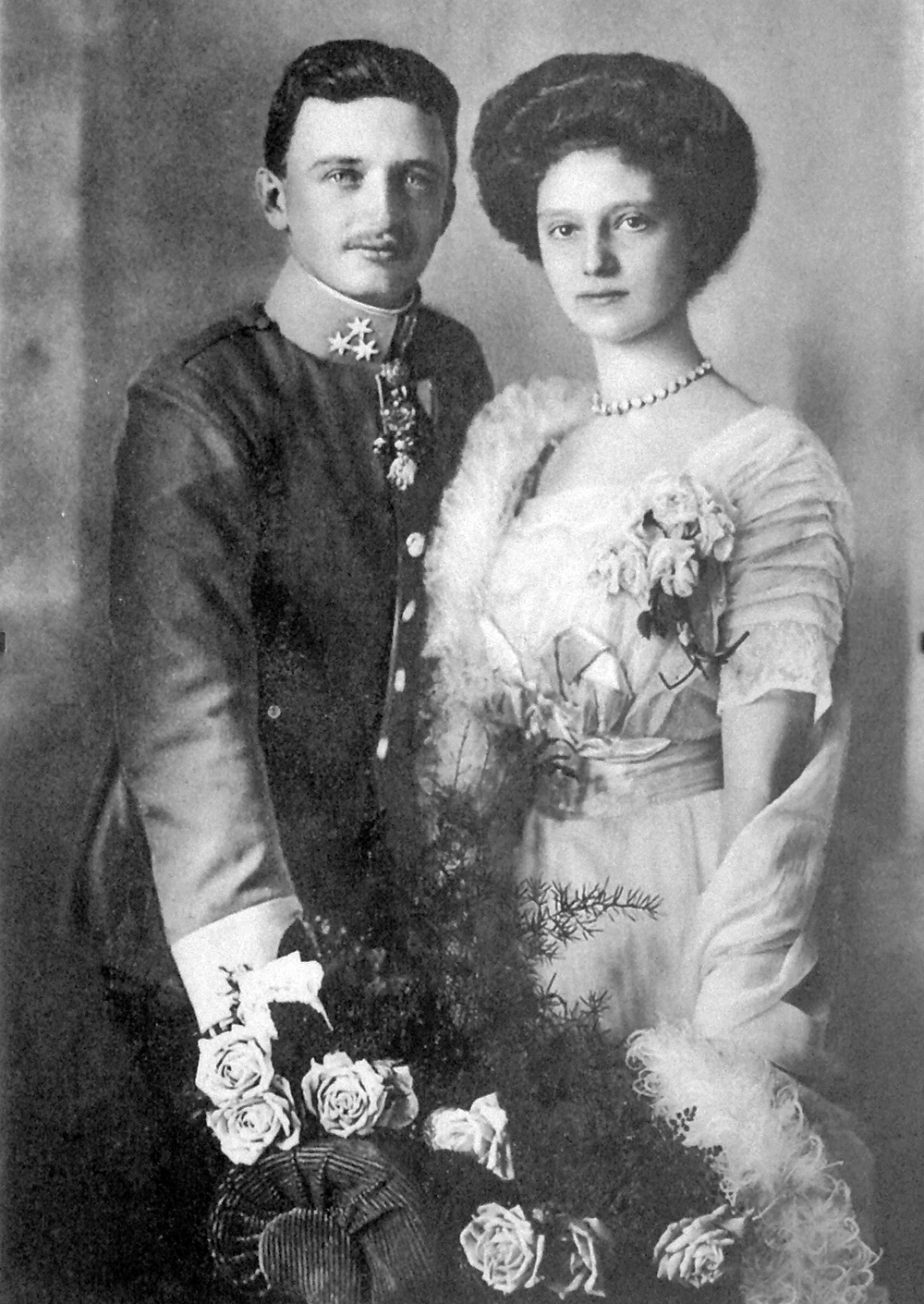

2.1. Engagement and Marriage

The Villa Wartholz, residence of Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria, Zita's maternal aunt, was located in close vicinity to Schwarzau Castle. Maria Theresa was the stepmother of Archduke Otto (who died in 1906) and the step-grandmother of Archduke Charles of Austria-Este, who was, at that time, second-in-line to the Austrian throne. Charles and Zita had met as children but did not see each other for nearly ten years as they pursued their education. In 1909, Charles's Dragoon regiment was stationed at Brandýs nad Labem, from where he visited his aunt at Františkovy Lázně. It was during one of these visits that Charles and Zita became reacquainted.

Charles was under pressure to marry, especially since his uncle and first-in-line, Franz Ferdinand, had married morganatically, excluding his children from the throne. Zita, with her suitably royal genealogy, was a fitting match. Zita later recalled that their feelings developed gradually over two years on her side, while Charles seemed to make up his mind much more quickly. When rumors spread in the autumn of 1910 that Zita was engaged to a distant Spanish relative, Don Jaime, the Duke of Madrid, Charles quickly sought out his grandmother, Archduchess Maria Theresa, to confirm the rumors were false. He then declared, "Well, I had better hurry in any case or she will get engaged to someone else."

Archduke Charles traveled to Villa Pianore and formally asked for Zita's hand in marriage. Their engagement was announced at the Austrian court on June 13, 1911, chosen to coincide with the feast day of Saint Anthony of Padua, after whom Zita's mother was named. Zita later recalled that after her engagement, she expressed her worries to Charles about the fate of the Austrian Empire and the monarchy's challenges. Before their wedding, Zita traveled to Rome at Charles's request, where on June 24, she received the blessing and consent of Pope Pius X. During this meeting, the Pope reportedly stated that Charles would be the next emperor.

Charles and Zita were married at Schwarzau Castle on October 21, 1911. Charles's great-uncle, the 81-year-old Emperor Franz Joseph I, attended the wedding. He was visibly relieved to see an heir make a suitable marriage and was in good spirits, even leading the toast at the wedding breakfast. The Imperial family and the public celebrated the union with great splendor, including a celebratory flight by the Wiener Neustadt air squadron the day before the wedding.

2.2. Princess of the Heir Apparent

Archduchess Zita soon conceived a son, and Otto was born on November 20, 1912, becoming third in line to the Imperial throne. Seven more children would follow in the next decade. At this time, Archduke Charles was in his twenties and did not expect to become emperor for some time, especially while Franz Ferdinand remained in good health.

This situation dramatically changed on June 28, 1914, when the heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, Sophie, were assassinated in Sarajevo by Bosnian Serb nationalists, an event that triggered World War I. Charles and Zita received the news by telegram that day. Zita remarked of her husband, "Though it was a beautiful day, I saw his face go white in the sun."

In the war that followed, Charles was promoted to General in the Austro-Hungarian army, taking command of the 20th Corps for an offensive in Tyrol. The war was personally difficult for Zita, as several of her brothers fought on opposing sides in the conflict. Prince Felix and Prince René had joined the Austrian army, while Prince Sixtus and Prince Xavier, who lived in France before the war, enlisted in the Belgian army. Furthermore, Zita's country of birth, Italy, joined the war against Austria in 1915, leading to whispers and rumors about the "Italian" Zita. As late as 1917, the German ambassador in Vienna, Count Botho von Wedel-Jarlsberg, wrote to Berlin stating, "The Empress is descended from an Italian princely house... People do not entirely trust the Italian and her brood of relatives."

At Franz Joseph's request, Zita and her children left their residence at Schloss Hetzendorf and moved into a suite of rooms at Schönbrunn Palace. Here, Zita spent many hours with the old Emperor on both formal and informal occasions, where Franz Joseph confided in her his fears for the future. Emperor Franz Joseph died of bronchitis and pneumonia at the age of 86 on November 21, 1916. Zita later recounted, "I remember the dear plump figure of Prince Lobkowitz going up to my husband, and, with tears in his eyes, making the sign of the cross on Charles's forehead. As he did so he said, 'May God bless Your Majesty.' It was the first time we had heard the Imperial title used to us."

2.3. Empress and Queen

Charles and Zita were crowned in Budapest on December 30, 1916. Following the coronation, there was a banquet, but the festivities were quickly concluded, as the emperor and empress believed it was inappropriate to have prolonged celebrations during wartime. At the beginning of their reign, Charles was often away from Vienna, so he had a telephone line installed from Baden, where his military headquarters were located, to the Hofburg, calling Zita several times a day when they were separated.

Zita exerted a discreet but significant influence on her husband. She would attend audiences with the Prime Minister or military briefings, and she developed a special interest in social policy, advocating for the welfare of the populace. While military matters remained Charles's sole domain, Zita, energetic and strong-willed, accompanied her husband to the provinces and to the front lines. She actively engaged in charitable works and made frequent visits to hospitals to comfort war-wounded soldiers, offering a human touch amidst the brutality of war. She also cared for war widows and orphans.

2.3.1. World War I and Political Role

Empress Zita played an active and supportive role during World War I, not only as a consort but also as a humanitarian. She was a constant source of strength and counsel for Emperor Charles, who often relied on her judgment. Her dedication to social policy led her to focus on improving conditions for soldiers and civilians affected by the war. She tirelessly visited hospitals, offering comfort and support to the wounded, and was involved in initiatives to provide aid to families suffering from the conflict. Her efforts aimed to alleviate the human cost of the war, demonstrating her deep compassion and commitment to her people.

2.3.2. The Sixtus Affair

By the spring of 1917, World War I was entering its fourth year, and Zita's brother, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, a serving officer in the Belgian Army, became a key figure in a secret diplomatic initiative. This plan aimed for Austria-Hungary to negotiate a separate peace with France, independent of its German ally. Emperor Charles initiated contact with Sixtus through intermediaries in neutral Switzerland, and Zita personally wrote a letter inviting her brother to Vienna, which her mother, Maria Antonia, delivered in person.

Sixtus arrived with conditions for talks that had been agreed upon with the French: the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine to France (annexed by Germany after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870), the restoration of Belgium's independence, independence for the Kingdom of Serbia, and the handover of Constantinople to Russia. Emperor Charles agreed, in principle, to the first three points and wrote a letter to Sixtus dated March 25, 1917, sending a "secret and unofficial message" to the President of France, stating, "I will use all means and all my personal influence."

This attempt at dynastic diplomacy ultimately failed. Germany vehemently refused to negotiate over Alsace-Lorraine and, seeing a Russian collapse on the horizon, was unwilling to give up the war. Sixtus continued his efforts, even meeting David Lloyd George in London to discuss Italy's territorial demands on Austria as outlined in the 1915 Treaty of London, but the British Prime Minister could not persuade his generals to make peace with Austria. Zita herself achieved a personal success during this period by intervening to stop German plans to bomb the home of the King and Queen of Belgium on their name days.

In April 1918, following the German-Russian Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Austrian Foreign Minister Count Ottokar Czernin delivered a speech attacking incoming French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau as the main obstacle to a peace favoring the Central Powers. Clemenceau was incensed and, upon seeing Emperor Charles's letter of March 24, 1917, had it published. For a while, Sixtus's life appeared to be in danger, and there were fears that Germany might even occupy Austria. Czernin persuaded Charles to send a "Word of Honour" to Austria's allies, asserting that Sixtus had not been authorized to show the letter to the French Government, that Belgium had not been mentioned, and that Clemenceau had lied about the mention of Alsace. Czernin had actually been in contact with the German Embassy throughout the crisis and attempted to persuade the Emperor to step down because of the affair. After failing to do so, Czernin resigned as Foreign Minister.

3. End of Empire and Exile

The final years of Zita's imperial life were marked by the dramatic collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, forcing her and her family into a long and arduous period of exile.

3.1. Collapse of the Empire and Abdication

By this time, the war was closing in on the embattled Emperor. A Union of Czech Deputies had already sworn an oath to a new Czechoslovak state independent of the Habsburg Empire on April 13, 1918. The prestige of the German Army had suffered a severe blow at the Battle of Amiens, and on September 25, 1918, Zita's brother-in-law, King Ferdinand I of Bulgaria, broke away from his allies in the Central Powers and sued for peace independently. Zita was with Charles when he received the telegram announcing Bulgaria's collapse. She remembered it "made it even more urgent to start peace talks with the Western Powers while there was still something to talk about." On October 16, the Emperor issued a "People's Manifesto" proposing that the empire be restructured on federal lines, with each nationality gaining its own state. Instead, each nation broke away, and the empire effectively dissolved.

Leaving their children behind at Gödöllő, Charles and Zita traveled to the Schönbrunn Palace. By this time, ministers had been appointed by the new state of "German-Austria," and by November 11, together with the Emperor's spokesmen, they prepared a manifesto for Charles to sign. Zita, at first glance, mistook it for an abdication and made her famous statement: "A sovereign can never abdicate. He can be deposed... All right. That is force. But abdicate - never, never, never! I would rather fall here at your side. Then there would be Otto. And even if all of us here were killed, there would still be other Habsburgs!" Charles gave his permission for the document to be published, and he, his family, and the remnants of his Court departed for the Royal shooting lodge at Eckartsau, close to the borders with Hungary and Slovakia. The Republic of German-Austria was proclaimed the next day.

3.2. Exile in Switzerland and Madeira

After a difficult few months at Eckartsau, the Imperial Family received aid from an unexpected source. Prince Sixtus had met King George V and appealed to him to help the Habsburgs. George was reportedly moved by the request, it being only months since his imperial relatives in Russia had been executed by revolutionaries, and promised, "We will immediately do what is necessary." Several British Army officers were sent to help Charles, most notably Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Lisle Strutt. On March 19, 1919, orders were received from the War Office to "get the Emperor out of Austria without delay." With some difficulty, Strutt managed to arrange a train to Switzerland, enabling the Emperor to leave the country with dignity without having to abdicate. Charles, Zita, their children, and their household left Eckartsau on March 24, escorted by a detachment of British soldiers from the Honourable Artillery Company under the command of Strutt.

The family's first home in exile was Wartegg Castle in Rorschach, Switzerland, a property owned by the Bourbon-Parmas. However, the Swiss authorities, concerned about the implications of the Habsburgs living near the Austrian border, compelled them to move to the western part of the country. The next month, therefore, found them moving to Villa Prangins, near Lake Geneva, where they resumed a quiet family life. This abruptly ended in March 1920 when, after a period of instability in Hungary, Miklós Horthy was elected regent. Charles was still technically King (as Charles IV), but Horthy sent an emissary to Prangins advising him not to go to Hungary until the situation had calmed. After the Treaty of Trianon, Horthy's ambition soon grew. Charles became concerned and requested the help of Colonel Strutt to get him into Hungary. Charles twice attempted to regain control, once in March 1921 and again in October 1921. Both attempts failed, despite Zita's staunch support; she insisted on traveling with him on the final dramatic train journey to Budapest.

Charles and Zita temporarily resided at Tata Castle, the home of Count Esterházy, until a suitable permanent exile could be found. Malta was mooted as a possibility but was declined by Lord Curzon, and French territory was ruled out given the possibility of Zita's brothers intriguing on Charles's behalf. Eventually, the Portuguese island of Madeira was chosen. On October 31, 1921, the former Imperial couple were taken by rail from Tihany to Baja, where the Royal Navy monitor HMS Glowworm was waiting. They finally arrived at Funchal on November 19. Their children were being looked after at Wartegg Castle in Switzerland by Charles's step-grandmother Maria Theresa, although Zita managed to see them in Zürich when her son Robert needed an operation for appendicitis. The children joined their parents in Madeira in February 1922.

Charles had been in poor health for some time. After going shopping on a chilly day in Funchal to buy toys for Carl Ludwig, he was struck by an attack of bronchitis. This rapidly worsened into pneumonia, not helped by the inadequate medical care available. Several of the children and staff were also ill, and Zita, at the time eight months pregnant, helped nurse them all. Charles weakened and died on April 1, 1922, at the age of 34, his last words to his wife being "I love you so much." After his funeral, a witness said of Zita, "This woman really is to be admired. She did not, for one second, lose her composure... she greeted the people on all sides and then spoke to those who had helped out with the funeral. They were all under her charm." Zita wore mourning black in Charles's memory throughout sixty-seven years of widowhood.

3.3. Exile in Belgium, North America, and Europe

After Charles's death, the former Austrian imperial family soon had to move again. Alfonso XIII of Spain approached the British Foreign Office via his ambassador in London, and they agreed to allow Zita and her seven (soon to be eight) children to relocate to Spain. Alfonso duly sent the warship Infanta Isabel to Funchal, which took them to Cadiz. They were then escorted to the Pardo Palace in Madrid, where shortly after her arrival, Zita gave birth to Archduchess Elisabeth. Alfonso XIII offered his exiled Habsburg relatives the use of Palacio Uribarren at Lekeitio on the Bay of Biscay. This appealed to Zita, who did not want to be a heavy burden to the state that harbored her. For the next six years, Zita settled in Lekeitio, where she dedicated herself to raising and educating her children. They lived with straitened finances, mainly on income from private property in Austria, a vineyard in Johannisberg in the Rhine Valley, and voluntary collections. However, other members of the exiled Habsburg dynasty claimed much of this money, and there were regular petitions for help from former Imperial officials.

By 1929, several of the children were approaching university age, and the family moved to a castle in the Belgian village of Steenokkerzeel near Brussels, where they were closer to several family members. Zita continued her political lobbying on behalf of the Habsburg family, even exploring links with Mussolini's Italy. There was even a possibility of a Habsburg restoration under Austrian Chancellors Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg, with Crown Prince Otto visiting Austria numerous times. These overtures were abruptly ended by the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938. As exiles, the Habsburg family took the lead in resisting the Nazis in Austria, but this foundered due to opposition between monarchists and socialists.

With the Nazi invasion of Belgium on May 10, 1940, Zita and her family became war refugees. They narrowly missed being killed by a direct hit on the castle by German bombers and fled to Prince Xavier's castle at Bostz in France. The Habsburgs then fled to the Spanish border, reaching it on May 18. On June 12, the Portuguese ruler António de Oliveira Salazar issued instructions to the Portuguese consulates in France to provide Infanta Maria Antónia of Portugal Duchess of Parma with Portuguese passports. With these Portuguese passports, the family could obtain visas without creating problems for the neutrality of the Portuguese Government. This way, Zita of Bourbon-Parma and her son Otto von Habsburg received their visas because they were descendants of a Portuguese citizen.

They moved on to Portugal and resided in Cascais. Not long after, Archduke Otto was informed by Salazar that Hitler had demanded his extradition. The demand would be refused, the Portuguese ruler told him, but hinted that his safety was precarious. On July 9, the United States government granted the family visas. After a perilous journey, they arrived in New York City on July 27, having family in Long Island and Newark, New Jersey. At one point, Zita and several of her children lived as long-term house-guests in Tuxedo Park, New York.

The Austrian imperial refugees eventually settled in Quebec, which had the advantage of being French-speaking, as the younger children were not yet fluent in English, and they continued their studies in French at Université Laval (Université LavalFrench). As they were cut off from all European funds, finances were more stretched than ever. At one stage, Zita was reduced to making salad and spinach dishes from dandelion leaves. However, all her sons were active in the war effort. Otto promoted the dynasty's role in a post-war Europe and met regularly with Franklin Roosevelt. Robert was the Habsburg representative in London. Carl Ludwig and Felix joined the United States Army, serving with several American-raised relatives of the Mauerer line. Rudolf smuggled himself into Austria in the final days of the war to help organize the resistance. In 1945, Empress Zita celebrated her birthday on the first day of peace, May 9. She spent the next two years touring the United States and Canada to raise funds for war-ravaged Austria and Hungary.

4. Personal Life and Faith

Throughout her life, Zita was defined by her unwavering Catholic faith, her deep devotion to her family, and her consistent engagement in social and charitable endeavors, especially during times of immense hardship.

4.1. Faith and Family

Zita's profound Catholic faith was a cornerstone of her life. She was known for her deep piety and devotion, which guided her actions and decisions. Her belief in the divine right of kings was so strong that she never accepted her husband Charles's abdication. Even after his death, she continued to refer to her eldest son, Otto, as "Emperor and King," believing that the Habsburg monarchy would one day be restored. This conviction was so deeply held that she was reportedly shocked and speechless when she learned that Otto had sworn loyalty to the Austrian Republic in 1961. Despite the political changes, she maintained hope that the Habsburg family would return to a monarchical role, noting that her descendants held succession rights in the royal houses of Spain, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Her devotion extended equally to her family. As a widowed mother at 29, Zita dedicated herself to raising her eight children with strong moral and religious values, particularly during their challenging years in exile. She ensured they received a good education and instilled in them a sense of duty and resilience, preparing them for their roles as members of a prominent European dynasty, even without a throne.

4.2. Social and Charitable Activities

From her youth, Zita was involved in humanitarian efforts. As a princess, she and her sister Francesca personally distributed food, clothing, and medicines to the needy in Pianore. As Empress, she continued these efforts, actively engaging in charitable works and hospital visits to the war-wounded soldiers, providing comfort and support. She also focused on social policy, aiming to alleviate the suffering of war widows and orphans. Even after the war and during her exile, Zita continued her humanitarian work, touring the United States and Canada to raise funds for war-ravaged Austria and Hungary, demonstrating her enduring commitment to helping those in need.

5. Later Life and Death

Zita's later life was characterized by a gradual return to Europe, a renewed connection with her former homeland, and a peaceful end to a life marked by imperial grandeur and profound personal sacrifice.

5.1. Return to Austria and Final Years

After a period of rest and recovery following World War II, Zita began to travel regularly back to Europe for the weddings of her children. In 1952, she decided to move back to the continent full-time, settling in Luxembourg to care for her aging mother, Maria Antonia, who died in 1959 at the age of 96. The bishop of Chur later proposed that Zita move into a residence he administered, formerly a castle of the Counts de Salis, at Zizers, Graubünden in Switzerland. Zita readily accepted this offer, as the castle provided ample space for visits from her large family and had a nearby chapel, a necessity for the devoutly Catholic Zita. She spent approximately 27 years in Zizers, dedicating her final decades to prayer.

Although restrictions on Habsburgs entering Austria had been lifted, this applied only to those born after April 10, 1919. This painful restriction meant that Zita could not attend the funeral of her daughter Adelheid in 1972. She also dedicated herself to the efforts to have her deceased husband, the "Peace Emperor," canonized. In 1982, the restrictions were eased, and she returned to Austria after being absent for six decades. Over the next few years, the Empress made several visits to her former Austrian homeland and even appeared on Austrian television. In a series of interviews with the Viennese tabloid newspaper Kronen Zeitung, Zita expressed her belief that the deaths of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria and his mistress Baroness Mary Vetsera, at Mayerling, in 1889, were not a double suicide but rather murder by French or Austrian agents.

5.2. Death and Funeral

After a memorable 90th birthday, at which she was surrounded by her now vast family, Zita's habitually robust health began to fail. She developed inoperable cataracts in both eyes. Her last major family gathering took place at Zizers in 1987, when her children and grandchildren joined in celebrating her 95th birthday. While visiting her daughter in the summer of 1988, she developed pneumonia and spent most of the autumn and winter bedridden. Finally, she called Otto in early March 1989 and told him she was dying. He and the rest of the family traveled to her bedside and took turns keeping her company until she died in the early hours of March 14, 1989. She was 96 years old and was the last surviving child of Robert, Duke of Parma, from both his marriages.

Her funeral was held in Vienna on April 1. The Austrian government allowed it to take place on Austrian soil, with the cost borne by the Habsburgs themselves. Zita's body was carried to the Imperial Crypt under the Capuchin Church in the same funeral coach she had walked behind during the funeral of Emperor Franz Joseph in 1916. The funeral was attended by over 200 members of the Habsburg and Bourbon-Parma families, and the service had 6,000 attendees, including leading politicians, state officials, and international representatives, including a representative of Pope John Paul II. Following an ancient custom, the Empress had asked that her heart, which was placed in an urn, remain at Muri Abbey in Switzerland, where the Emperor's heart had rested for decades. In doing so, Zita ensured that in death, she and her husband would remain by each other's side. When the procession of mourners arrived at the gates of the Imperial Crypt, the herald who knocked on the door during the traditional "admission ceremony" introduced her as Zita, Her Majesty the Empress and Queen. During the funeral, Mozart's Requiem was performed in its entirety, and the imperial anthem, "God Save Emperor Franz", was sung, marking the first time this former national anthem resonated in St. Stephen's Cathedral since the establishment of the Republic.

6. Cause for Sainthood

Zita's deep piety and unwavering faith led to the formal opening of her cause for beatification and canonization within the Catholic Church. On December 10, 2009, Mgr Yves Le Saux, Bishop of Le Mans, France, officially opened the diocesan process for Zita's beatification. Zita had a habit of spending several months each year in the diocese of Le Mans at St. Cecilia's Abbey, Solesmes, where three of her sisters were nuns.

With the opening of her cause, the late Empress has been named a Servant of God. The process is supported by the French Association pour la Béatification de l'Impératrice Zita, with Alexander Leonhardt serving as the postulator for the cause, Norbert Nagy as the vice postulator for Hungary, Bruno Bonnet as the judge of the tribunal, and François Scrive as the promoter of justice. Her husband, Charles I, has already been beatified, and his feast day is notably celebrated on October 21, their wedding anniversary. This choice suggests a strong possibility that Zita may eventually join him on the Catholic altar, recognizing their shared spiritual journey and devotion.

7. Titles, Styles, Honours, and Arms

7.1. Titles and Styles

- May 9, 1892 - October 21, 1911: Her Royal Highness Zita, Royal Princess of Bourbon, Princess of Parma

- October 21, 1911 - June 28, 1914: Her Imperial and Royal Highness Archduchess Zita, Archduchess Karl of Austria, Princess of Parma

- June 28, 1914 - November 21, 1916: Her Imperial and Royal Highness The Archduchess of Austria-Este

- November 21, 1916 - April 3, 1919: Her Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty The Empress of Austria, Apostolic Queen of Hungary and Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia

7.2. Honours

- Austria-Hungary:

- Grand Mistress Dame of the Order of the Starry Cross

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Elisabeth, 1913

- Knight Grand Officer of the Order of the Red Cross, with War Decoration

- SMOM: Bailiff Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Saint John

8. Children

Charles and Zita had eight children and thirty-three grandchildren:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Prince Otto von Habsburg | November 20, 1912 | July 4, 2011 | Married (1951) Princess Regina of Saxe-Meiningen (January 6, 1925 - February 3, 2010) and had seven children, twenty-two grandchildren and ten great-grandchildren. |

| Archduchess Adelheid | January 3, 1914 | October 2, 1971 | Never married, no issue. |

| Robert, Archduke of Austria-Este | February 8, 1915 | February 7, 1996 | Married (1953) Princess Margherita of Savoy-Aosta (April 7, 1930 - January 10, 2022) and had five children, nineteen grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. |

| Archduke Felix of Austria | May 31, 1916 | September 6, 2011 | Married (1952) Princess Anna Eugenie von Arenberg (July 5, 1925 - June 9, 1997) and had seven children and twenty-two grandchildren. |

| Archduke Carl Ludwig | March 10, 1918 | December 11, 2007 | Married (1950) Princess Yolanda of Ligne (May 6, 1923 - September 13, 2023) and had four children, nineteen grandchildren and ten great-grandchildren. |

| Archduchess Charlotte | March 1, 1921 | July 23, 1989 | Married (1956) Duke Georg of Mecklenburg (October 5, 1899 - July 6, 1963). No children. |

| Archduchess Elisabeth | May 31, 1922 | January 6, 1993 | Married (1949) Prince Heinrich of Liechtenstein (August 5, 1916 - April 17, 1991) and had five children, seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. |

9. Ancestry

Zita of Bourbon-Parma's ancestry traces back through prominent European royal houses, including the Houses of Bourbon-Parma, Portugal, and Habsburg.

- 1. Zita of Bourbon-Parma

- 2. Robert I, Duke of Parma

- 3. Infanta Maria Antonia of Portugal

- 4. Charles III, Duke of Parma

- 5. Princess Louise of Artois

- 6. Miguel I of Portugal

- 7. Princess Adelaide of Löwenstein

- 8. Charles II, Duke of Parma

- 9. Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy

- 10. Prince Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry

- 11. Princess Marie Caroline of Naples and Sicily

- 12. John VI of Portugal and Brazil

- 13. Infanta Carlota Joaquina of Spain

- 14. Constantine, Hereditary Prince of Löwenstein

- 15. Princess Agnes of Hohenlohe-Langenburg