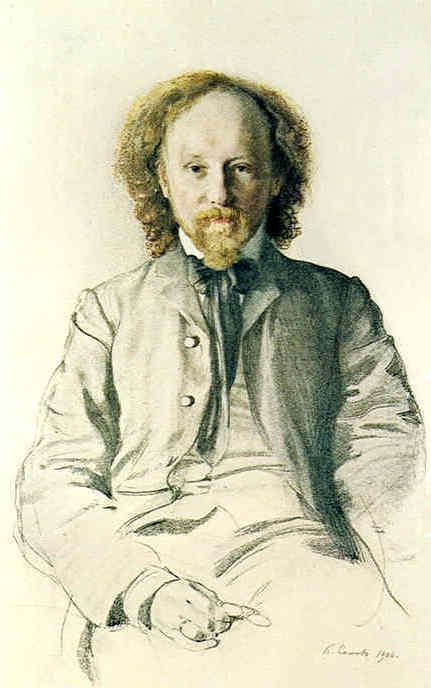

1. Early Life and Education

Vyacheslav Ivanov's early life was shaped by his family background and a rigorous academic pursuit that laid the foundation for his later intellectual and artistic endeavors.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Born in Moscow on 28 February 1866, Vyacheslav Ivanov came from the lower Russian nobility. He lost his father, a minor civil servant, at the young age of five. Consequently, he was raised by his deeply religious mother within the traditions of the Russian Orthodox Church, who believed her son was destined to become a poet.

1.2. Education and Early Influences

Ivanov graduated from the First Moscow Gymnasium with a gold medal, demonstrating early academic prowess. He then enrolled at Moscow University, where he pursued studies in history and philosophy under the tutelage of scholars like Paul Vinogradoff. In 1886, he moved to Berlin University to further his education, focusing on Classics, Roman law, and economics under the renowned Theodor Mommsen, a Nobel laureate in Literature. During his time in Imperial Germany, Ivanov was deeply influenced by the poetry and philosophy of German Romanticism, notably the works of Novalis, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. His most passionate interest, however, lay in researching the intricate connection between the ancient Greek religious cult of Dionysus and its worship during the Bacchanalia with the emergence of theatre of ancient Greece. From 1892, he continued his studies in Rome, focusing on archaeology and successfully completing his doctoral dissertation there.

2. Personal Life and Relationships

Ivanov's personal life was complex and deeply intertwined with his intellectual and spiritual development, marked by significant relationships and emotional experiences.

2.1. First Marriage and Relationship with Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal

In 1886, Ivanov married Darya Mikhailovna Dmitrievskaya, the sister of his close childhood friend, Aleksei Dmitrievsky. He initially aspired to a conventional family life. However, in 1893, while studying in Rome, he met Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal, a well-to-do amateur singer, poet, and translator who had recently separated from her husband. Lydia was also a distant relative of Russia's national poet Alexander Pushkin, sharing a common ancestor in the 17th-century Afro-Russian military officer and aristocrat Abram Petrovich Gannibal.

Influenced by his recent discovery and enthusiasm for the philosophical writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Ivanov and Zinovieva-Annibal succumbed to their mutual attraction during a "tempestuous night at the Colosseum, which he described in verse as a ritualistic breaking of taboos and regeneration of ancient religious fervor." This event led to a significant shift in his personal life. In 1895, Ivanov's wife and daughter separated from him. On 15 April 1896, Lydia gave birth to Ivanov's second daughter, also named Lydia. Both Ivanov and Zinovieva-Annibal were granted Orthodox ecclesiastical divorces, under the terms of which they were ruled the guilty parties and consequently forbidden a Russian Orthodox wedding. To circumvent this, they adopted a common practice of the time: in 1899, they dressed in costumes deliberately reminiscent of the ancient Greek cult of Dionysus and were married in a Greek Orthodox ceremony in Livorno, Italy. Despite the rejection of traditional Christian morality implied by the adulterous beginning of their relationship and their decision to have an open marriage, Ivanov paradoxically reflected, "Through each other we discovered ourselves - and more than ourselves: I would say that we found God."

2.2. Second Marriage

After Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal's death in 1907, Ivanov experienced a period of profound grief, during which he reportedly slipped into theosophy and spiritualism, becoming emotionally and financially vulnerable to a fraudulent medium. This medium claimed to be able to summon Lydia from the afterlife. However, the medium eventually departed after Ivanov had a dream in which his late wife instructed him to marry Vera Shvarsalon, Lydia's daughter from her first marriage. He married 23-year-old Vera in the summer of 1913, following the birth of their son, Dmitry, in 1912. Vera's death in 1920, at the age of 30, was another devastating blow to Ivanov.

2.3. Children

Vyacheslav Ivanov had at least two daughters. His first daughter was from his marriage to Darya Mikhailovna Dmitrievskaya. His second daughter, also named Lydia, was born on 15 April 1896, to Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal. He also had a son, Dmitry, born in 1912, with Vera Shvarsalon.

3. Intellectual and Artistic Development

Vyacheslav Ivanov's intellectual and artistic development was a dynamic process, shaped by profound philosophical and religious influences, extensive classical studies, and a pioneering role in the Russian Symbolist movement.

3.1. Philosophical and Religious Influences

Ivanov's philosophical framework was deeply influenced by a diverse array of thinkers. Friedrich Nietzsche was a particularly significant figure; Ivanov, like his hero Vladimir Solovyov, interpreted Nietzsche as a "Christian thinker in spite of himself," applying New Testament concepts to Nietzsche's anti-Christian worldview. This unique interpretation allowed Ivanov to reconcile seemingly disparate ideas. The German idealist tradition, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and German Romanticism, also played a crucial role in shaping his thought. Furthermore, Slavicism and the philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov significantly contributed to his intellectual development, particularly in his later spiritual journey towards Christian unity.

3.2. Classical Studies and Dionysian Cult

Ivanov's academic research into classical antiquity was central to his intellectual identity. He was considered one of Russia's foremost Greek scholars. His main passionate interest was in exploring the connection between the ancient Greek religious cult of Dionysus and its worship during the Bacchanalia with the creation of theatre of ancient Greece. He summarized his Dionysian ideas in the treatise The Hellenic Religion of the Suffering God (1904), which, following Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy, traced the roots of literature in general and the art of tragedy in particular to ancient Dionysian mysteries. He interpreted Dionysus not merely as a pagan deity but as an avatar for Jesus Christ, a concept that allowed him to synthesize classical and Christian thought.

3.3. Russian Symbolism and Theatre Theory

Ivanov was a senior literary and dramatic theorist of the Russian Symbolist movement, particularly influential in its second phase. He spearheaded a significant shift in Russian Symbolism, moving it away from the intentions of Valery Bryusov to emulate French Symbolism and the concept of art for art's sake. Instead, Ivanov guided the movement towards Philhellenism, Neoclassicism, Germanophilia, and, crucially, towards the recent German philosophy and dramatic theories of both Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Ivanov's most radical contributions were his theories for social and spiritual renewal through theatre. He sought to blur and even erase the fourth wall in theatre, aiming to transform the audience into active participants in the dramas they attended. He proposed the creation of a new type of mass theatre, which he called a "collective action," modeled on ancient religious rituals, Athenian tragedy, and the medieval mystery play. In his 1904 essay "Poèt i Čern" (Poet and the Mob), he argued for a revival of the ancient relationship between the poet and the masses. Inspired by The Birth of Tragedy and Wagner's theory of Gesamtkunstwerk, Ivanov sought to provide a philosophical foundation for his proposals by linking Nietzsche's analysis with Leo Tolstoy's Christian religious movement and ancient Dionysian dramas with later Christian mystery plays. Through the use of the mask, he argued, the tragic hero would appear not as an individual character but as the embodiment of a fundamental Dionysian reality, "the one all-human I." This staged myth would grant the people access to a sense of the "total unity of suffering."

Rejecting theatrical illusion (mimesis), Ivanov's modern liturgical theatre would offer action itself (praxis). This would be achieved by overcoming the separation between stage and auditorium, adopting an open space similar to the classical Greek orchêstra, and abolishing the division between actors and audience, so that all became co-creating participants in a sacred rite. He envisioned performances where furniture was distributed "by whim and inspiration," and actors mingled with the audience, handing out masks and costumes, before collective improvisation would merge all participants into a communal unity through singing and dancing as a chorus. Ivanov believed that theatre could facilitate a genuine spiritual revolution in culture and society, arguing in Po zvezdam (1908) that "theatres of the chorus tragedies, the comedies and the mysteries must become the breeding-ground for the creative, or prophetic, self-determination of the people." He even suggested that "only... when the choral voice of such communities becomes a genuine referendum of the true will of the people will political freedom become a reality."

While some, like the director Vsevolod Meyerhold, enthusiastically embraced Ivanov's ideas, others remained skeptical. The poet Andrei Bely criticized the impracticality of abolishing class divisions through masks and costumes, stating, "While the class struggle still exists, these appeals for an aesthetic democratization are strange."

3.4. Religious Conversion and Theology

A significant turning point in Ivanov's life was his conversion in 1926 to the Russian Greek Catholic Church, one of the smallest of the Eastern Catholic Churches. This conversion followed a life that he later described as so hedonistic that he compared it to that of St. Augustine. On 17 March 1926, he formally joined the Church, pronouncing a prayer for reunification composed by his hero Vladimir Solovyov and making a standard abjuration under oath of all theological principles upon which Russian Orthodoxy differs from Catholicism.

In a 1930 open letter explaining his conversion to Charles Du Bos, Ivanov recalled feeling "Orthodox in the full sense of the word for the first time in my life" upon pronouncing the Creed and formula of adherence. He described his previous state as like a "consumptive" breathing with "only one lung," emphasizing his belief in the necessity of unity between the Eastern and Western Christian traditions. In a 1937 interview for the Russicum's newspaper, Ivanov argued that prior to the Great Schism, Latin and Byzantine Christianity were "two principles that mutually complement each other." He criticized the Russian Orthodox Church for its perceived failure to effectively challenge the regressive secularization of pre-1917 Russian culture, attributing it partly to the lack of an indigenous tradition of active monasticism, similar to the views of Fyodor Dostoevsky in The Brothers Karamazov. Ivanov concluded that "The Church must permeate all branches of life: social issues, art, culture, and just everything. The Roman Church corresponds to such criteria and by joining this Church I become truly Orthodox." Literary scholar Robert Bird confirms that Ivanov, deeply influenced by Vladimir Solovyov and Fyodor Dostoevsky, viewed his conversion "as an extension rather than a rejection of Russian Orthodoxy," seeing it as preordained by Solovyov's philosophy.

4. Literary Career and Works

Vyacheslav Ivanov's literary career spanned poetry, plays, essays, and translations, showcasing his profound erudition and innovative approaches to art and thought.

4.1. Poetry

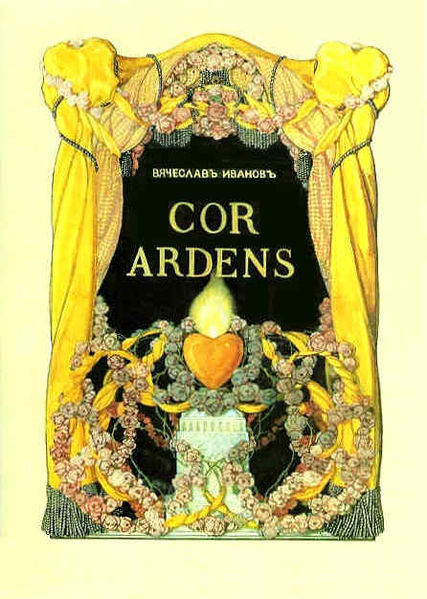

Ivanov's poetic achievements began with his first collection, Lodestars (Кормчие звёздыKormchie zvyozdyRussian, 1903), which included many pieces written a decade earlier. This collection was highly praised by leading critics as a new chapter in Russian Symbolism. Other poetry collections include Transparency (ПрозрачностьProzrachnost'Russian, 1904), Eros (ЭросErosRussian, 1907), Cor Ardens (Cor ardensCor ardensRussian, 1911-1912), a two-volume work containing poems written about his late wife, Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal, and Tender Secret (Нежная тайнаNezhnaya taynaRussian, 1912). His poems were often compared to those of John Milton and Vasily Trediakovsky due to their detached, calculated archaism. According to literary scholar Robert Bird, Ivanov, much like his contemporary T.S. Eliot, heavily utilized "epigraphs from a host of languages... and in a variety of alphabets." He also experimented with "grafting Classical Greek metres and syntax onto Russian verse" and reveled in "obscure archaisms and recondite allusions to antiquity."

His later years in Rome inspired Roman Sonnets (Римские сонетыRimskie sonetyRussian, 1925) and his Roman Diary (1944), which reflected on the traditional feast days of both Russian and Roman Rites, Christian theology, and the chaos of World War II in Rome. His 1918 poem Infancy (МладенчествоMladenchestvoRussian) and 1939 collection Man (ЧеловекChelovekRussian) are also notable. His final volume of Russian poetry, Svet vechernii (The Evening Light), was published posthumously in 1962. His posthumous mystical allegory, Povest' o Svetomire tsareviche: Skazanie starce-inoke (The Tale of Tsarevich Svetomir, as Told by a Holy Monk), is considered by some to hold the key to his entire artistic and spiritual quest, showing a muting of the Neoplatonic and Nietzschean tones of his earlier, more pagan-philosophical works in the light of his rediscovered Christian faith.

4.2. Plays and Dramatic Theory

Ivanov wrote two plays during his career: Tantalus (1905) and Prometheus (1919). Both works imitated the dramatic structure and mythological subject-matter of Aeschylean tragedy and were written in obscure and archaic language. His musical tragicomedy Love - Mirage (Любовь - МиражLyubov' - MirazhRussian) was published in 1923. However, it was his unrealized, utopian ideas about theatre, rather than the plays themselves, that proved far more influential. His theoretical concepts for theatre, emphasizing collective action and the dissolution of the boundary between actors and audience, were a significant contribution to avant-garde dramatic thought, influencing figures like Vsevolod Meyerhold.

4.3. Essays and Criticism

Ivanov's critical writings and philosophical essays were integral to his intellectual output. His treatise The Hellenic Religion of the Suffering God (1904) laid out his Dionysian theories. Other significant collections of essays include Po zvezdam (Following the Stars, По звёздамPo zvyozdamRussian, 1909) and Borozdy i mezhi (Furrows and Boundaries, Борозды и межиBorozdy i mezhiRussian, 1916). His monograph Dostoevsky: Tragedy - Myth - Mysticism (in German) was published in 1932. Many of his Symbolist theories were elaborated in a series of articles, which were later revised and reissued as Simbolismo in 1936. His Dostoevsky scholarship was published posthumously as Freedom and the Tragic Life in 1952. He also wrote a Russian language commentary on the Christian Bible after his conversion to the Russian Greek Catholic Church.

4.4. Translations

Ivanov was a prolific translator, focusing on ancient and Renaissance authors. He translated works by Sappho, Alcaeus, Aeschylus, and Petrarch into the Russian language. Beyond literary works, his "golden pen" was sought after by the Jesuits of the Russian Apostolate and the Vatican for transforming elegant Latin into equally refined Old Church Slavonic. His translations included Biblical texts, litanies to the Sacred Heart and Immaculate Heart, the Salve Regina, the texts of the Jesuit vows, and invocations to the Little Flower.

5. "The Tower" Salon

"The Tower" was an influential literary salon hosted by Vyacheslav Ivanov and Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal in St. Petersburg, becoming a pivotal gathering point for the Russian Symbolist movement.

5.1. Establishment and Significance

After capturing the attention of Russian Symbolist poet Valery Bryusov with his lectures on the cult of Dionysus in Paris in 1903, Vyacheslav and Lydia Ivanov made a triumphant return to St. Petersburg in 1905. They were widely celebrated as foreign curiosities and established a literary salon known as "Среды ИвановаSredy IvanovaRussian" (Ivanov Wednesdays), more famously referred to as "On the Tower" due to its location. This salon was situated in their seventh-floor apartment, which overlooked the gardens of the Tauride Palace in St. Petersburg. To accommodate the increasing number of talented and often disputatious individuals who flocked to the Wednesday soirees, walls and partitions within the apartment were reportedly torn down. These gatherings typically did not reach their full swing until after supper, which was served around 2 A.M.

"The Tower" quickly became the most fashionable literary salon of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, even amidst the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the meetings of the First Duma across the road. The Ivanovs exerted an enormous influence upon the Russian Symbolist movement, with many of its main tenets being formulated within their turreted house. The intellectual cross-fertilization that occurred at "The Tower" was a social manifestation of Symbolist principles, which viewed divisions between various fields of knowledge and artistic disciplines as artificial, linking poetry intimately not only to painting, music, and drama, but also to philosophy, psychology, religion, and myth.

5.2. Key Figures and Discussions

"The Tower" attracted a wide array of prominent writers, philosophers, and artists who engaged in diverse and stimulating discussions. Among the frequent attendees were poets like Alexander Blok and Anna Akhmatova, philosophers such as Nikolai Berdyaev, artists like Konstantin Somov, and dramatists including Vsevolod Meyerhold.

Nikolai Berdyaev, a close friend and former student of Ivanov, often presided over these gatherings. He described Ivanov as a man who "succeeded in combining an intense poetical imagination with an amazing knowledge of Classical philology and Greek religion. He was a philosopher and a theologian; a theosophist and a political publicist. There was no object upon which he could not throw some new and unexpected light." Nicholas Zernov further noted that Ivanov brought together people of the most diverse views and convictions, including "Christians and sceptics, monarchists and republicans, Symbolists and Classicists, occultists and mystical anarchists," all welcomed as long as they were original, daring, and ready for hours of discussion. The salon was a forum for debates on religion, philosophy, literature, and politics, often accompanied by music and poetry recitations.

Among the notable interactions at the salon, Ivanov helped discover the poet Anna Akhmatova. She recalled meeting him in 1910, when her then-husband Nikolai Gumilev first brought her to "The Tower." Akhmatova read some of her verse aloud, to which Ivanov ironically quipped, "What truly heavy romanticism." She later expressed indignation that Ivanov would often weep during her recitations but then "vehemently criticize" the same poems at other literary salons, a slight she never forgave. Ivanov also tried to persuade Akhmatova to leave her husband, suggesting, "You'll make him a man if you do." However, Akhmatova, along with Gumilev and Osip Mandelstam, went on to found the Acmeist movement, which explicitly rejected Ivanov and Symbolism. Akhmatova's ultimate assessment of Ivanov was that he was "neither grand nor magnificent (he thought this up himself) but a 'catcher of men.'"

Other significant events at "The Tower" included a staging of Calderón's Adoration of the Holy Cross by Vsevolod Meyerhold on 19 April 1910, with many important figures of Russian literature present or performing. In 1912, Ivanov met Fr. Leonid Feodorov, a priest of the then-illegal Russian Greek Catholic Church, and discussed his essay "Thoughts about Symbolism." Feodorov later noted Ivanov's sympathies towards the Catholic Church and the Byzantine Rite, though he found them based on "motives of an aesthetic and mystical character, of quite vague and extremely whimsical fantasies."

The salon also witnessed the growing ideological rifts within Russian Symbolism. By 1910, the movement was splitting into two hostile camps: one, led by Ivanov, represented the theurgist line (rooted in Vladimir Solovyov's philosophy), while the opposing camp, with Valery Bryusov as its spokesman, rejected Symbolism's claims to transcend art and fuse art with life for religious or mystical goals.

Maria Skobtsova, then an acclaimed Symbolist poet and frequent guest, later became a Russian Orthodox nun and martyr. Decades later, living in Paris as an anti-communist White émigré who had returned to her ancestral religious roots, Skobtsova expressed deep shame recalling the hedonistic atmosphere among the intellectuals at "The Tower." She believed that she and her colleagues could have learned much from any rural peasant woman praying in her Orthodox parish church, lamenting their detachment: "We lived in the middle of a vast country as if on an uninhabited island... We played out the last act of the tragedy concerned with the rift between the intelligentsia and the people."

6. Later Life and Emigration

Vyacheslav Ivanov's later life was marked by the tumultuous events of the Russian Revolution, his eventual emigration, and a distinguished academic career in Europe.

6.1. Post-Revolutionary Russia

Following the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War, Ivanov moved to Baku in 1920, where he held the University Chair of Classical Philology. During this period, he concentrated on his scholarly work, completing the treatise Dionysus and Early Dionysianism (published 1923), which earned him a Ph.D. degree in philology.

Despite his academic achievements, the new Marxist-Leninist government initially prevented Ivanov and his family from emigrating from the Soviet Union. However, through the influence of his former protege Anatoly Lunacharsky, who was then the People's Commissar of Education, exit visas were finally granted in 1924.

6.2. Emigration to Italy

From Azerbaijan, Ivanov proceeded to Italy, fulfilling his desire to live and die in Rome. He first settled in Pavia, where he served as Professor of Russian literature between 1926 and 1934. He was subsequently elected professor of Russian literature at the University of Florence, but the government of Fascist Italy refused to allow him to take up the position. In 1934, Ivanov and his family finally arrived in Rome, an event he later commemorated in the sonnet Regina Viarum (1924). Ivanov explained his reasons for becoming a refugee, stating, "I was born free, and the silence there (i.e., in Soviet Russia) leaves an aftertaste of slavery."

6.3. Academic Career in Europe

In Europe, Ivanov proved himself to be a "consummate European," eloquently conversant in all major European languages and possessing erudition of rare breadth and depth. He allied himself with representatives of the religious and cultural revival that occurred in many countries between the wars. While teaching Old Church Slavonic liturgical language, the vernacular Russian language, and Russian literature at the Pontifical Oriental Institute, Ivanov and his children were formally received as Eastern Rite Catholics into the Russian Greek Catholic Church.

Beginning on 11 February 1936, Ivanov also taught as professor of Church Slavonic and eventually many other subjects at the Russicum, a Byzantine Rite Catholic major seminary and Russian-language immersion school in Rome. The Russicum had been established by Pope Pius XI in 1929 to train priests of the Russian Greek Catholic Church for missionary work in the Soviet Union and the Russian diaspora. Ivanov's students at the Russicum included future Greek Catholic Martyr Bishop Theodore Romzha, as well as Gulag survivors and memoirists Frs. Walter Ciszek and Pietro Leoni. His lectures on Russian literature at the Russicum were considered so challenging that only native Russian speakers and the most advanced seminarians attended. Between 1939 and 1940, Ivanov gave a celebrated series of lectures on the novels of Dostoevsky, and during Russian Christmas in 1940, he gave a reading of several of his own works of Christian poetry about the Nativity of Jesus Christ.

6.4. European Intellectual Activity

Despite his lack of a steady income and worries about his son Dmitry's health, Ivanov became a "minor star in the European intellectual firmament" by the early 1930s. His intellectual status was further bolstered in 1931 by a successful public defense of Christianity during a debate against Benedetto Croce, who had traveled with a large entourage from Milan specifically for the occasion.

In the emigration, Ivanov continued to write essays for leading journals in sophisticated German, Italian, and French. Though his reputation never reached the heights it had in Russia, these essays attracted a highly literate, albeit small, coterie of admirers, including Martin Buber, Ernst Robert Curtius, Charles Du Bos, Gabriel Marcel, and Giovanni Papini. His services as a translator were eagerly sought by the Jesuits of the Russian Apostolate and the Vatican, where his "golden pen deftly transformed elegant Latin into an equally refined Church Slavonic." He remained active as a poet and scholar until his very last day, producing Roman Sonnets (1924) and his Roman Diary (1944) during his Roman years. The Roman Diary poems, which pondered the violence and chaos of life in Rome during the Second World War, secretly made their way back to the Soviet Union through Samizdat, where Eugenia Gertsyk embraced them as the fulfillment of her long-standing hopes that Ivanov, like his hero Goethe, "would achieve... clarity and wisdom in old age."

7. Death

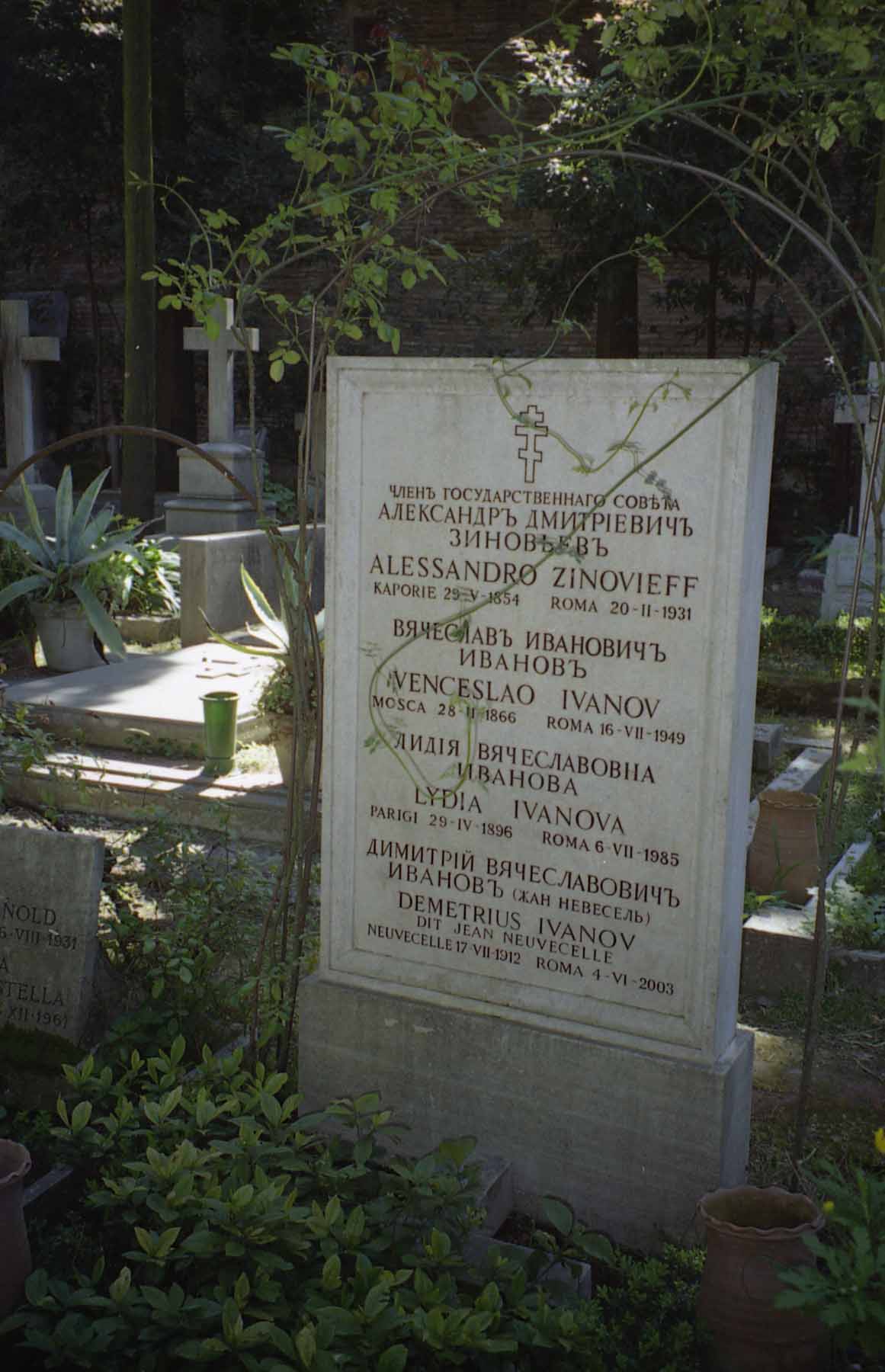

Vyacheslav Ivanov died in Rome, after a short illness, in his apartment at three o'clock in the afternoon on 16 July 1949. Although he died a believing Catholic, he had arranged to be buried with two of his poetic heroes, John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, at the Cimitero Acattolico (Protestant Cemetery). Ivanov's grave is located not far from those of fellow Russian exiles Karl Briullov and Alexander Ivanov.

8. Legacy and Assessment

Vyacheslav Ivanov's posthumous influence and critical reception have evolved over time, particularly with the changing political landscape in his homeland.

8.1. Posthumous Reception and Revival

Following his death, the reading and study of Ivanov's writings continued to be encouraged by scholars such as C.M. Bowra and Sir Isaiah Berlin, both of whom he had met in 1946. Through their influence, an English translation of Ivanov's significant Dostoevsky scholarship was published as Freedom and the Tragic Life in 1952. His final volume of Russian poetry, Svet vechernii (The Evening Light), was published posthumously in 1962.

However, in the Soviet Union, Ivanov's works were subject to government censorship and were not republished for decades. It became inadvisable, if not impossible, to study them, and his name was largely relegated to a footnote in the history of pre-revolutionary literature. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ivanov became the beneficiary of renewed attention. His books were republished, and he has since been repeatedly the subject of essays, monographs, and conferences, leading to a great revival of interest in his work. In particular, his Russian language commentary on the Christian Bible, written in Rome after his conversion to the Russian Greek Catholic Church, has become one of his most widely circulated published writings since the fall of communism.

8.2. Critical Assessment

Various critical perspectives and historical evaluations have shaped the understanding of Ivanov's works and thought. Sir Isaiah Berlin, in Russian Thinkers, noted that the search for one's place in the moral and social universe, a central tradition in Russian literature, continued until the 1890s revolt of the neo-classical aesthetes and Symbolists under figures like Ivanov and Balmont. However, Berlin observed that these movements, despite their splendid fruits, did not last long as an effective force, as the Soviet revolution later returned to the "crude and distorted utilitarian form" of Vissarion Belinsky and the social criteria of art.

Robert Bird suggests that Ivanov's 1926 conversion to Catholicism and his decision to isolate himself from the main currents of White émigré and Soviet life contributed to an "image of near-sanctity." Bird also highlights that the late reawakening of Ivanov's poetic muse in 1944 serves as an eloquent reminder that, in the final analysis, he remained "first and foremost, a lyric poet held captive by eternity and struggling to define a place in history." His later works show a muting of the Neoplatonic and Nietzschean tones of his earlier, more pagan-philosophical works, in the light of his rediscovered Christian faith.

8.3. Influence on Movements and Thought

Ivanov's influence extended significantly to various fields, including Russian Symbolism, theatre theory, and religious thought. He was instrumental in guiding the second phase of Russian Symbolism away from its French origins towards a more distinct Russian character, incorporating elements of Philhellenism, Neoclassicism, and German philosophy. His radical dramatic theories, particularly his concept of "collective action" and the dissolution of the fourth wall, profoundly influenced avant-garde theatre directors like Vsevolod Meyerhold.

In the realm of religious thought, Ivanov's unique synthesis of Dionysian and Christian themes, and his later conversion to the Russian Greek Catholic Church, left a notable mark. His belief in the mutual complementarity of Latin and Byzantine Christianity and his vision for the Church to permeate all aspects of life resonated with certain intellectual circles. Gustav Wetter, a former Russicum seminarian, recalled Ivanov summarizing the main tenets of Russian Symbolism with two quotations: Goethe's "Alles vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis" ("Everything ephemeral is only a reflection") and the principle of ascent of the human mind, "a realibus ad realiora" ("From what is real to what is more real"). Wetter noted that these principles profoundly influenced his own thought.

9. Related Topics

- Vyacheslav Ivanov's work

- Olga Schor