1. Overview

Vojislav Šešelj, born on October 11, 1954, is a prominent Serbian politician and a convicted war criminal. He is the founder and president of the far-right Serbian Radical Party (SRS). His political career saw him serve as the Deputy Prime Minister of Serbia between 1998 and 2000. Šešelj is widely known for his extreme nationalist ideology, particularly his advocacy for a "Greater Serbia" and his controversial stances on ethnic minorities. His involvement in the Yugoslav Wars led to his indictment by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for crimes against humanity and war crimes. After a lengthy and contentious trial process, which included his self-representation and periods of hunger strike, he was provisionally released due to health issues. While initially acquitted on all counts by the ICTY, the verdict was later partially reversed by the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), convicting him of crimes against humanity related to the instigation of deportation and persecution of Croats in Hrtkovci. His life and political actions have left a significant and controversial impact on Serbian politics, nationalism, and regional human rights.

2. Early life and Education

Vojislav Šešelj's early life and academic pursuits laid the groundwork for his later political and ideological development.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Vojislav Šešelj was born on October 11, 1954, in Sarajevo, which was then part of the People's Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. His parents, Nikola Šešelj (1925-1978) and Danica Šešelj (née Misita; 1924-2007), were Serbs who had moved to Sarajevo from the Popovo Valley region of eastern Herzegovina after their marriage in 1953. The family lived modestly, with his father employed by the state-run ŽTP railway company and his mother caring for Vojislav and his younger sister, Dragica. A notable relative on his mother's side was Chetnik commander Lt. Col. Veselin Misita.

2.2. Education

Šešelj began his elementary education in September 1961 at Vladimir Nazor Primary School before transferring to the newly constructed Bratstvo i Jedinstvo primary school. Although initially a successful student, he gradually became disinterested in the curriculum, realizing he could achieve adequate grades with minimal effort. History was his favorite subject, and he generally preferred social sciences over natural sciences.

For his secondary education, Šešelj enrolled at First Sarajevo Gymnasium, where he earned good grades. He actively participated in student organizations, serving as the president of the gymnasium's student union and later as the president of its youth committee. During summer holidays while at the gymnasium, he continued to participate in youth work actions, working as a laborer building embankments along the Morava River in 1972 and 1973.

After completing his secondary education, Šešelj enrolled in the University of Sarajevo's faculty of law in autumn 1973. He became involved in student bodies, serving as a vice-dean counterpart in the student organization for fifteen months. He openly criticized Fuad Muhić, a candidate for dean, publicly proclaiming him unfit for the position, though Muhić was still elected. Šešelj also worked as a course demonstrator, holding weekly tutorials and assisting professors with oral exams and conference papers. In 1975, as part of a university delegation, the 21-year-old Šešelj visited the University of Mannheim in West Germany for two weeks, marking his first trip abroad. He completed his four-year undergraduate studies in an exceptionally short period of two years and eight months.

Immediately after graduating in 1976, Šešelj sought an assistant lecturer position at the University of Sarajevo's faculty of law, but no such positions were available for the following academic year, a situation he attributed to personal revenge by Muhić for his earlier criticism. He then considered applying to the faculty of law in Mostar and the Faculty of Political Science in Sarajevo for a "Political Parties and Organizations" course taught by Atif Purivatra, a friend of Muhić. Fearing rejection, he withdrew his application and learned through a friend's mother, who was the faculty's dean, that a new department for people's defense would require many assistants.

In November 1976, Šešelj began postgraduate studies at the University of Belgrade's faculty of law. Due to his employment obligations in Sarajevo, he traveled to Belgrade two to three times a month for lectures and literature. He earned a master's degree in June 1977 with a thesis titled The Marxist Concept of an Armed People. In 1978, he spent two and a half months in the United States at the Grand Valley State Colleges as part of an exchange program with the University of Sarajevo.

Also in 1978, after returning from the U.S., Šešelj pursued a doctorate at the Belgrade University's faculty of law. After submitting his dissertation in late autumn 1979, he specialized at the University of Greifswald in East Germany. He earned his doctorate on November 26, 1979, after successfully defending his dissertation titled The Political Essence of Militarism and Fascism, making him the youngest PhD holder in Yugoslavia at 25 years of age. In December 1979, Šešelj joined the Yugoslav People's Army for his mandatory military service, stationed in Belgrade, completing it in November 1980. During this period, he lost his position at the University of Sarajevo's faculty of political sciences.

3. Academic Career and Early Political Activities

Vojislav Šešelj's academic career was marked by increasing political activism and significant clashes with the communist regime, which ultimately propelled him into the forefront of Serbian nationalist politics.

3.1. Academic Career and Political Persecution

In the early 1980s, Šešelj began to associate with dissident intellectuals in Belgrade, many of whom held Serbian nationalist views. He openly blamed Muslim professors at the faculty of political sciences, including his former friend Atif Purivatra, Hasan Sušić, and Omer Ibrahimagić, for hindering his career, denouncing them as Pan-Islamists.

In September 1981, Šešelj rejoined the faculty of political sciences, where he was assigned to teach international relations. Given the faculty's role in shaping future politicians, it was under strict control by the Communist Party. Šešelj quickly attracted the attention of party officials due to his outspoken nature. He publicly supported Nenad Kecmanović, another intellectual facing criticism from parts of the Bosnian communist nomenklatura for his writings in NIN magazine.

The most significant controversy arose when Šešelj confronted his faculty colleague, Brano Miljuš, a protégé of Hamdija Pozderac and Branko Mikulić, who were then the highest political figures in the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Šešelj meticulously analyzed Miljuš's master's thesis and accused him of plagiarizing over 40 pages from published works by Karl Marx and Edvard Kardelj. Šešelj extended his criticism to the highest political echelons, particularly Pozderac, who had reviewed Miljuš's thesis. This power struggle escalated beyond the faculty, spilling into political institutions. Despite support from some intellectuals like Boro Gojković, Džemal Sokolović, Hidajet Repovac, Momir Zeković, and Ina Ovadija-Musafija, the Pozderac faction proved stronger. Šešelj was expelled from the Communist League of Bosnia and Herzegovina on December 4, 1981.

By spring 1982, only six months after his re-hiring, Šešelj's position at the faculty of political sciences became precarious. He was demoted to the Institute for Social Research, an affiliated institution. Intellectuals in Belgrade rallied to his defense, sending letters of protest to the government of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Faculty of Political Science in Sarajevo.

Šešelj became increasingly critical of Yugoslavia's approach to the national question. He advocated for the use of force against Kosovo Albanians and denounced the Serbian political leadership's passivity in handling the Kosovo crisis. He also argued that the Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina were not a nation but a religious group, expressing concern that Bosnia and Herzegovina would become a Muslim-dominated republic.

He came under surveillance by UDBA (secret police) agents. His first arrest occurred on February 8, 1984, during the Sarajevo Olympics. He was on a train to Belgrade when secret police boarded near Podlugovi station, seizing his writings. Among the arresting agents was Dragan Kijac, who later became the state security chief of Republika Srpska. Šešelj was taken off the train in Doboj, transported to Belgrade, questioned for 27 hours, and then released. Upon returning to Sarajevo, UDBA questioned him twice more, with agents Rašid Musić and Milan Krnjajić. Šešelj claimed they had transcripts of his conversations with friends, trying to make him implicate them for a "group trial for ethnic balance purposes, [...] a Serbian group to persecute since they just convicted Izetbegović's Muslim one." On April 20, 1984, he was arrested in a private apartment in Belgrade among 28 individuals attending a lecture by Milovan Đilas as part of the Free University, a semi-clandestine organization of intellectuals critical of the communist regime. He spent four days in prison before being released.

However, his freedom was short-lived. In mid-May 1984, Stane Dolanc, a Slovene representative in the Presidency of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and a long-time state security chief, gave a TV Belgrade interview about Šešelj's unpublished manuscript, Odgovori na anketu-intervju: Šta da se radi?. In this manuscript, Šešelj called for "reorganization of the Yugoslav federalism, SFR Yugoslavia with only four constituent republics (Serbia, Macedonia, Croatia and Slovenia), abolishing of the single-party system, and the abolishing of artificial nationalities."

Two days later, on May 15, 1984, Šešelj was arrested again in Sarajevo. After being jailed at Sarajevo's Central Prison, he began a 28-day hunger strike, drawing international press attention. Despite being told of his son Nikola's birth (named after his father), he refused to end the strike until the last day of his trial, lasting 48 days. Weakened and frail, he finally relented. On July 9, 1984, he was sentenced to eight years in prison by presiding judge Milorad Potparić, who concluded that Šešelj "acted from the anarcho-liberal and nationalist platform thereby committing the criminal act of counterrevolutionary endangerment of the social order." The primary evidence was his unpublished manuscript. On appeal, the Supreme Court of SFR Yugoslavia reduced his sentence progressively to two years.

Šešelj served the first eight months in Sarajevo before being transferred to Zenica prison in January 1985. There, he was quarantined and isolated for three weeks for medical and psychological observation to devise a rehabilitation plan. He immediately informed prison officials of his refusal to perform any labor, arguing that "since jailed communists didn't have to do prison labor in the pre-World War II capitalist Yugoslavia, I too, as someone espousing anti-communist ideology, refuse to do labour in a communist prison." His defiance resulted in multiple stays in solitary confinement, initially two weeks, later extended to a month. During his first solitary confinement, he began another hunger strike, enduring 16 days without food despite being beaten by guards. Out of his fourteen months in Zenica, six and a half were spent in solitary confinement. He was released in March 1986, two months early, due to continuous pressure, protests, and petitions from intellectuals across Yugoslavia and abroad, many of whom later became his political opponents. Upon release, Šešelj permanently moved to Belgrade. According to John Mueller, Šešelj "later seems to have become mentally unbalanced as the result of the torture and beatings he endured while in prison."

3.2. Founding of Parties and Early Activities

Upon moving to Belgrade, Šešelj rapidly became involved in the burgeoning political landscape. In late 1989, alongside Vuk Drašković and Mirko Jović, he co-founded the anti-communist Chetnik party, Serbian National Renewal (SNO).

In March 1990, he and Drašković formed the monarchist party Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO), which he soon left to establish the more radical Serbian Chetnik Movement (SČP). Due to its name, the SČP was denied official registration. In March 1991, it merged with the National Radical Party (NRS) to form the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), with Šešelj as its president. He notoriously described himself and his supporters as "not fascists, just chauvinists who hate Croats."

3.3. Chetnik Vojvoda Title

In 1989, Šešelj traveled to the United States, where Momčilo Đujić, a Chetnik leader from World War II in Yugoslavia living in exile, bestowed upon him the title of Chetnik vojvoda (Vojvoda of the Chetniks). This was the first such title granted since World War II, given with the stated aim of creating a "unitary Serbian state where all Serbs would live, occupying all the Serb lands." However, by 1997, Đujić expressed regret for awarding the title to Šešelj due to his later cooperation with Slobodan Milošević's Socialist Party of Serbia.

4. Ideology and Political Stances

Vojislav Šešelj's political thought is deeply rooted in extreme nationalism, with a particular focus on the concept of a "Greater Serbia" and a highly critical, often discriminatory, view of ethnic minorities.

4.1. Greater Serbia and Nationalism

Šešelj is a staunch advocate for a "Greater Serbia," a nationalist ideology aiming to unite all Serbs into a single state, often at the expense of other ethnic groups and existing national borders. He propagated a vision of "Greater Serbia" defined by the Virovitica-Karlovac-Karlobag line, which would encompass significant portions of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as parts of Vojvodina in Serbia. This expansionist ideology underpinned his entire political platform and was central to the Serbian Radical Party's program. In 1995, he authored a memorandum in the publication Velika Srbija (Greater Serbia) that outlined the "Serbianization" of Kosovo, demonstrating his commitment to this nationalist objective.

4.2. Stances on Minorities and Human Rights

Šešelj's views and rhetoric concerning ethnic minorities and human rights have been widely condemned for their exclusionary and inflammatory nature. He publicly advocated for the ethnic cleansing of all Croats and Bosniaks from territories he envisioned as part of "Greater Serbia." In late 1991, during the Battle of Vukovar, he visited Borovo Selo and publicly described Croats as a "genocidal and perverted people." He also called for the forcible deportation of 360,000 Albanians from Kosovo, advocating violence and expulsion against them and their leadership with the aim of discrediting them in Western public opinion.

His disregard for human rights extended to freedom of the press and the work of human rights organizations. In September 1998, while serving as Deputy Prime Minister, he openly objected to foreign media and human rights organizations operating in Yugoslavia. He threatened that if they were found to be "participated in the service of foreign propaganda" (naming organizations like Voice of America, Deutsche Welle, Radio Free Europe, Radio France International, and BBC radio), they "shouldn't expect anything good" during times of aggression. He specifically mentioned "various Helsinki committees and Quisling groups" as targets if NATO planes could not be reached. These statements were strongly condemned by Human Rights Watch.

5. Role in the Yugoslav Wars

Vojislav Šešelj played a significant and controversial role during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, marked by his alleged links to paramilitary groups and direct instigation of ethnic cleansing campaigns.

5.1. Association with Paramilitary Groups

During the Yugoslav Wars, the paramilitary group known as the White Eagles was reportedly associated with Vojislav Šešelj, often referred to as Šešeljevci ("Šešelj's men"). These groups were implicated in numerous atrocities and human rights violations. While various reports and indictments linked him to these organizations, Šešelj consistently denied any direct association, stating, "In previous wars (Bosnia, Croatia) there was a small paramilitary organisation called White Eagles, but the Serb Radical Party had absolutely nothing to do with them."

5.2. Persecution Campaign in Hrtkovci

A particularly egregious example of Šešelj's direct involvement in ethnic cleansing was the campaign in the Vojvodina village of Hrtkovci. In May and July 1992, Šešelj personally visited Hrtkovci and initiated a systematic campaign of persecution and expulsion targeting the local ethnic Croat population. This campaign involved public threats and intimidation, leading to the forced displacement of numerous Croat families from their homes, illustrating his direct role in orchestrating ethnic cleansing.

5.3. Incitement to Violence and Ethnic Cleansing

Šešelj's public speeches and statements were frequently characterized by inflammatory rhetoric that allegedly incited violence, hatred, and ethnic cleansing. The prosecution at his war crimes trial contended that he recruited paramilitary groups and incited them to commit atrocities during the Balkan wars. His calls for a "Greater Serbia" were often accompanied by demands for the removal of non-Serb populations. For instance, he advocated the forcible removal of all Albanians from Kosovo. Such pronouncements contributed significantly to the climate of fear and violence that fueled wartime atrocities and regional instability.

6. Political Career in Serbia

Vojislav Šešelj's political career in Serbia was dynamic and often turbulent, marked by shifting alliances, periods of opposition, and significant government roles, all of which profoundly impacted the country's political landscape.

6.1. Relationship with Slobodan Milošević

Šešelj's relationship with Serbian President Slobodan Milošević was complex and evolved significantly throughout the 1990s. During the initial years of the Yugoslav Wars, Šešelj and his Serbian Radical Party (SRS) maintained an amicable and close alliance with Milošević's Socialist Party of Serbia. This alliance was instrumental in orchestrating the mass layoffs of journalists in 1992, and Šešelj publicly affirmed his support for Milošević as late as August 1993. However, their relationship deteriorated in September 1993 when Šešelj and Milošević clashed over Milošević's withdrawal of support for Republika Srpska in the Bosnian War. Milošević publicly denounced Šešelj as "the personification of violence and primitivism." This led to Šešelj's imprisonment in 1994 and 1995 for his opposition to Milošević. The SRS subsequently became the main opposition party, criticizing Milošević for corruption, ties to organized crime, nepotism, and poor economic conditions. Despite this period of opposition, as violence escalated in the Serbian province of Kosovo in 1998, Šešelj rejoined Milošević's national unity government, briefly aligning with the pro-Milošević administration.

6.2. Deputy Prime Minister and Government Participation

In 1998, following his reconciliation with Milošević, Vojislav Šešelj was appointed Deputy Prime Minister of Serbia. His party, the Serbian Radical Party, participated in the government, influencing governance and social issues during this period. His tenure as Deputy Prime Minister lasted until 2000.

6.3. Stance during the Kosovo War and NATO Bombing

During the Kosovo War and the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999, Šešelj and the Serbian Radical Party remained loyal supporters of Milošević. However, after three months of intense bombardment, they stood as the only party to vote against United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244, which mandated the withdrawal of FR Yugoslav security forces from Kosovo. Šešelj vehemently opposed any withdrawal from Kosovo and continued to advocate for the forcible removal of all Albanians from the region, demonstrating his unwavering hard-line nationalist stance even in the face of international pressure.

7. ICTY/MICT Indictment, Trial, and Verdicts

Vojislav Šešelj's legal battles with the international tribunal for war crimes represent a significant chapter in his life, marked by controversy and shifting judicial outcomes.

7.1. Indictment Details

The initial indictment against Vojislav Šešelj was filed on February 14, 2003. In an interview for NIN on February 4, 2003, Šešelj stated he had inside information about his impending indictment by The Hague and had already booked a flight for February 24.

The indictment charged Šešelj, both individually and as part of a "joint criminal enterprise," with committing crimes in violation of Articles 3 and 5 of the Tribunal's Statute. These alleged crimes included the "permanent forcible removal" of the majority Croat, Muslim, and other non-Serb populations from approximately one-third of Croatia, large parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and from parts of Vojvodina in Serbia. The ultimate goal of this enterprise was "to make these areas part of a new Serb-dominated state." Specifically, Šešelj was charged with 15 counts, including eight counts of crimes against humanity and six counts of war crimes. These charges encompassed persecution of Croats, Muslims, and other non-Serbs in Vukovar, Šamac, Zvornik, and Vojvodina, as well as murder, forced deportation, illegal imprisonment, torture, and property destruction during the Yugoslav Wars.

7.2. Custody and Trial Proceedings

On February 23, 2003, following a "farewell meeting" held at Republic Square in Belgrade, Vojislav Šešelj surrendered to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). He was transferred to the ICTY the following day, facing charges for his alleged participation in a joint criminal enterprise.

His trial, which officially began on November 7, 2007, was marred by significant controversy. Šešelj insisted on representing himself, a right he secured after a 28-day hunger strike in December 2006. During proceedings, he regularly insulted the judges and court prosecutors. In 2005, he gained notoriety for reading a letter he had sent to the ICTY, which contained insults and expletives aimed at top ICTY officials and judges, including referring to Carla Del Ponte as "the prostitute." While in custody, he authored Kriminalac i ratni zločinac Havijer Solana (Felon and War Criminal Javier Solana), criticizing the then Secretary General of NATO for his role in the 1999 Kosovo War.

In December 2006, approximately 40,000 people marched in Belgrade in support of Šešelj during his hunger strike. Aleksandar Vučić, then secretary of the Serbian Radical Party, declared at the rally, "He's not fighting just for his life. But he's fighting for all of us who are gathered here. Vojislav Šešelj is fighting for Serbia!" Šešelj ended his hunger strike on December 8 after being granted the right to present his own defense. While still in custody, he led his party's list of contenders for the January 2007 general election in Serbia.

The trial faced multiple interruptions. On February 11, 2009, after 71 witnesses had been heard, the presiding judges suspended Šešelj's trial indefinitely at the prosecution's request, citing witness intimidation. Šešelj countered that the prosecutors were losing their case and had presented false witnesses to avoid acquitting him, demanding damages for his "suffering and six years spent in detention." One of the three judges voted against the suspension, deeming it "unfair to interrupt the trial of someone who has spent almost six years in detention."

Šešelj was also charged with and convicted of contempt of court on multiple occasions. On July 24, 2009, he was sentenced to 15 months in detention for revealing the identities of three protected witnesses in a book he had written, whose names had been ordered suppressed by the tribunal. He was charged a second time for contempt on March 10, 2010, for allegedly disclosing court-restricted information on 11 protected witnesses. His trial resumed on January 12, 2010, and continued until March 17, 2010, when it was again adjourned pending checks on the health status of remaining witnesses.

In September 2011, the ICTY rejected Šešelj's bid to have his trial discontinued, despite his argument that his right to be tried within a reasonable time had been violated. The court ruled that "there is no predetermined threshold with regard to the time period beyond which a trial may be considered unfair on account of undue delay" and stated that Šešelj "failed to provide concrete proof of abuse of process." In closing remarks at his war crimes trial on March 14, 2012, Šešelj asserted that the ICTY was a creation of Western intelligence agencies and lacked jurisdiction in his case, vowing "to make a mockery of his trial." Prosecutors had demanded a 28-year sentence for his alleged role in recruiting paramilitary groups and inciting them to commit atrocities.

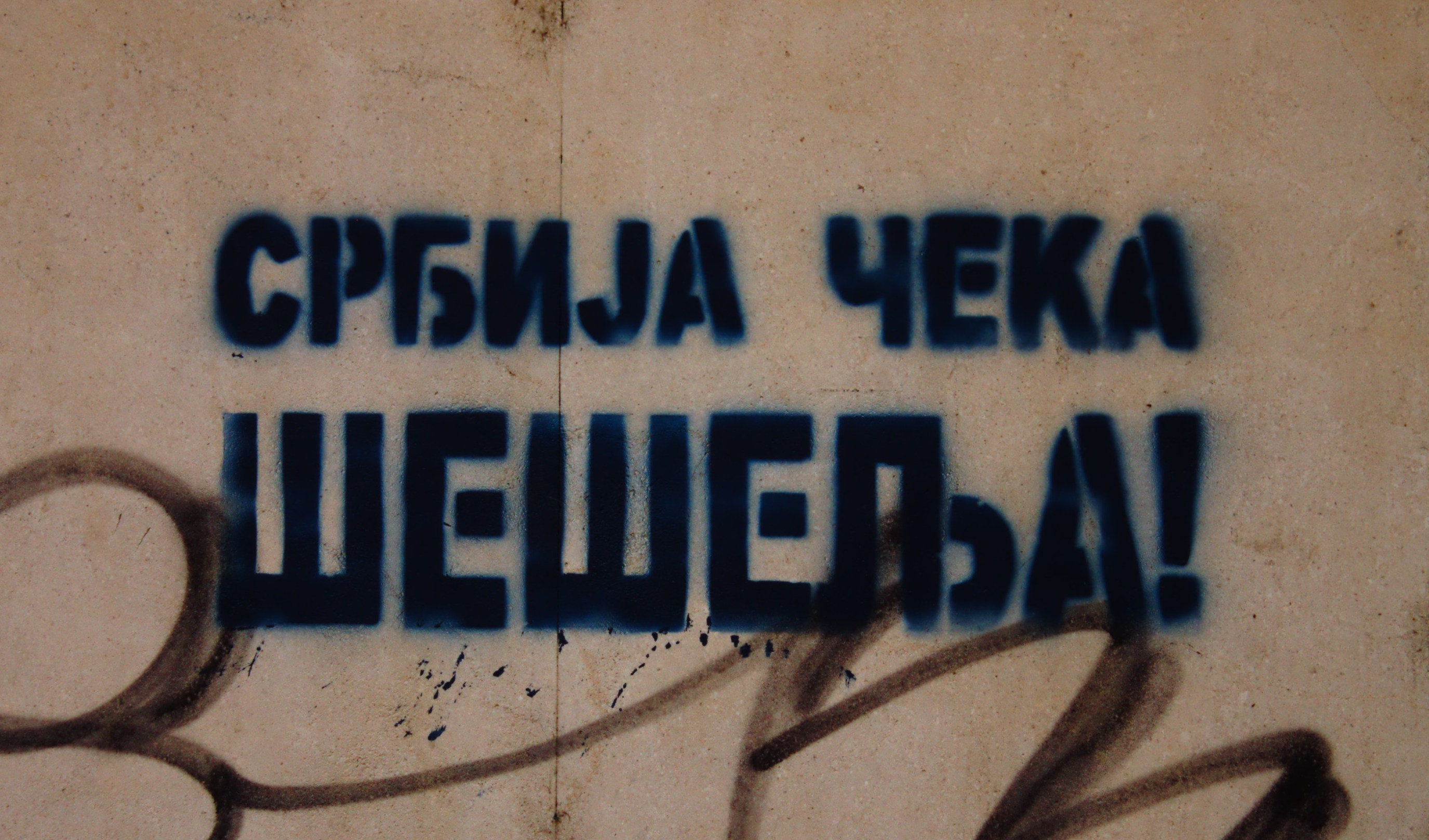

7.3. Provisional Release and Health Issues

On November 6, 2014, the ICTY granted Šešelj provisional release. This decision was made primarily due to his diagnosis of metastatic cancer and his deteriorating health. The ICTY did not publicly disclose the specific conditions of his release, but it was announced that he was not permitted to leave Serbia, was to have no contact with victims and witnesses, and was required to return to ICTY custody if summoned. Šešelj returned to Belgrade to a welcome from thousands of sympathizers, having spent 11 years and 9 months in detention in the United Nations Detention Unit of Scheveningen during his inconclusive trial.

7.4. First Verdict (Acquittal)

On March 31, 2016, one week after the conviction of Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, the ICTY delivered its first-instance verdict in Šešelj's case, finding him not guilty on all charges. The decision was a majority one on eight counts and unanimous on one. The Economist described his acquittal as "a victory for advocates of ethnic cleansing" that would have "broad ramifications for international justice." At the time, Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić commented that the case against Šešelj was inherently flawed and politicized from the beginning.

7.5. Reversal of Acquittal and Conviction

The initial acquittal was subsequently appealed by prosecutors from the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), which functions as an oversight and successor entity to the ICTY. On April 11, 2018, the Appeals Chamber partially reversed the first-instance verdict. Šešelj was found guilty under Counts 1, 10, and 11 for instigating deportation, persecution (forcible displacement), and other inhumane acts (forcible transfer) as crimes against humanity. These convictions stemmed specifically from his speech in Hrtkovci on May 6, 1992, in which he called for the expulsion of Croats from Vojvodina. He was sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment. However, because he had already served more than 11 years in ICTY custody pending trial, the sentence was declared served, meaning he was not obligated to return to prison. He was found not guilty on the remaining counts of his indictment, including all other war crimes and crimes against humanity alleged to have been committed in Croatia and Bosnia. In August 2018, Šešelj submitted a request to the MICT Appeals Chamber to appeal the April 11, 2018, decision, but this request was denied due to an absence of evidence demonstrating errors in the judgment or violations of his procedural rights. Amnesty International welcomed the conviction, stating it delivered "long overdue justice to victims."

8. Personal Life and Health

Beyond his public and political persona, Vojislav Šešelj's personal life has included family and significant health challenges.

8.1. Family Life

Vojislav Šešelj is married to Jadranka Šešelj (Јадранка ШешељSerbian), who was born in Podujevo on April 13, 1960. Jadranka is a member of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS) and participated in the 2012 Serbian presidential election, though she failed to pass the first round, securing 3.78% of the votes. Vojislav and Jadranka have a son named Nikola, who was born while Vojislav was in prison.

8.2. Health Condition

Šešelj was diagnosed with metastatic cancer. He underwent surgery to remove a tumor from his colon on December 19, 2013. Following the surgery, he received chemotherapy treatments. His deteriorating health due to this condition was a primary reason for his provisional release from ICTY custody in November 2014.

9. Writings and Honors

Vojislav Šešelj is a prolific writer, and his public life has also seen him receive certain honors, reflecting aspects of his controversial public persona.

9.1. Books and Publications

Šešelj has authored a vast number of books, totaling 183 publications. These works largely consist of court documents, transcripts from interviews, and records of his public appearances. Many of his book titles are polemical, often formulated as direct insults targeting his political opponents, ICTY judges and prosecutors, and various domestic and foreign political figures. A notable example is Kriminalac i ratni zločinac Havijer Solana (Felon and War Criminal Javier Solana), which criticized the NATO Secretary General for his role in the 1999 Kosovo War.

9.2. Honors Received

On January 29, 2015, Vojislav Šešelj received the White Angel honor at the Mileševa Monastery. This honor was bestowed upon him by the Serbian Orthodox bishop Filaret, sparking controversy due to Šešelj's background as a convicted war criminal.

10. Assessment and Impact

Vojislav Šešelj's career has profoundly influenced Serbian politics and society, leaving a controversial and divisive legacy, particularly concerning nationalism and human rights.

10.1. Historical and Social Evaluation

Vojislav Šešelj's role in Serbian politics, nationalism, and the Yugoslav Wars is widely viewed with significant criticism and controversy. He is considered a central figure in the rise of extreme Serbian nationalism in the late 20th century, advocating for a "Greater Serbia" through means that included ethnic cleansing. His rhetoric and actions during the wars, particularly his instigation of the persecution of Croats in Hrtkovci, have been condemned as contributing to widespread human rights violations and undermining democratic norms. His trial and eventual conviction for crimes against humanity by an international tribunal underscore the severe nature of his alleged offenses and their impact on victims and inter-ethnic relations in the region. Despite his legal battles and the controversies surrounding him, Šešelj has maintained a significant political presence and a loyal following in Serbia, reflecting the enduring appeal of his nationalist ideology among certain segments of the population.

10.2. Impact on Politics and Society

Šešelj's long-term influence on Serbian political discourse is undeniable. He has consistently pushed the boundaries of nationalist rhetoric, shaping public debate and contributing to the polarization of Serbian society. His Serbian Radical Party, even during his detention, remained a notable force in Serbian politics, demonstrating the lasting resonance of his ideas. His actions and speeches during the Yugoslav Wars contributed to regional instability and the suffering of countless victims, leaving deep scars on inter-ethnic relations. The legacy of his involvement in the conflicts continues to hinder efforts towards societal reconciliation and justice in the post-Yugoslav era. His political career exemplifies the challenges of confronting extreme nationalism and ensuring accountability for wartime atrocities, with his impact extending to the present-day political landscape of Serbia.