1. Overview

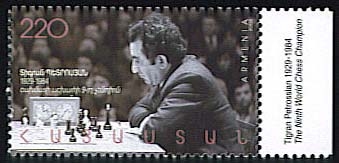

Tigran Vardani Petrosian, born on June 17, 1929, and passing away on August 13, 1984, was a prominent Soviet-Armenian chess grandmaster and the ninth World Chess Champion, holding the title from 1963 to 1969. He earned the nickname "Iron Tigran" due to his almost impenetrable defensive playing style, which prioritized safety above all else. Petrosian is widely credited with significantly popularizing chess in Armenia. He was a candidate for the World Chess Championship on eight occasions, demonstrating remarkable consistency at the highest levels of the sport. He secured the World Championship title in 1963 by defeating Mikhail Botvinnik, successfully defended it in 1966 against Boris Spassky, and eventually lost it to Spassky in 1969. This made him either the defending World Champion or a World Championship Candidate in ten consecutive three-year cycles. Petrosian also achieved success in domestic competitions, winning the USSR Chess Championship four times in 1959, 1961, 1969, and 1975. He held a degree of Master of Philosophical Science, with his 1968 thesis titled "Chess Logic, Some Problems of the Logic of Chess Thought." Authors of a 2004 book recognized him as the most difficult player to defeat in the history of chess.

2. Early Life

Tigran Petrosian's formative years were marked by both personal hardship and the early development of his profound connection to chess, shaped by influential theorists and dedicated mentorship.

2.1. Birth and Childhood

Petrosian was born to Armenian parents on June 17, 1929, in Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, which is present-day Georgia. As a young boy, Petrosian was an excellent student and enjoyed studying, a trait he shared with his brother Hmayak and sister Vartoosh. He began learning to play chess at the age of eight. Despite his early interest, his illiterate father, Vartan, encouraged him to continue his academic studies, believing that chess was unlikely to provide a successful career path.

During World War II, Petrosian was orphaned and faced severe hardships, including being forced to sweep streets to earn a living. He later recalled this period in a 1969 interview: "I started sweeping streets in the middle of the winter and it was horrible. Of course there were no machines then, so we had to do everything by hand. Some of the older men helped me out. I was a weak boy. And I was ashamed of being a street sweeper-that's natural, I suppose. It wasn't so bad in the early morning when the streets were empty, but when it got light and the crowds came out I really hated it. I got sick and missed a year in school. We had a babushka, a sister of my father, and she really saved me. She gave me bread to eat when I was sick and hungry. That's when this trouble with my hearing started. I don't remember how it all happened. Things aren't very clear from that time." It was around this difficult time that his hearing began to deteriorate, a condition that would affect him throughout his life.

2.2. Education and Early Influences

Despite the poverty, Petrosian used his rations to purchase Chess Praxis by Danish grandmaster Aron Nimzowitsch, a book he later cited as having the greatest influence on his development as a chess player. He also acquired The Art of Sacrifice in Chess by Rudolf Spielmann. Another significant early influence on Petrosian's chess was José Raúl Capablanca.

At the age of 12, Petrosian began formal training at the Tiflis Palace of Pioneers under the tutelage of Archil Ebralidze. Ebralidze, an admirer of Nimzowitsch and Capablanca, advocated a scientific approach to chess that discouraged risky tactics and dubious combinations. This mentorship helped Petrosian develop a repertoire of solid positional openings, such as the Caro-Kann Defence. After just one year of training at the Palace of Pioneers, he notably defeated visiting Soviet grandmaster Salo Flohr in a simultaneous exhibition.

By 1946, Petrosian had earned the title of Candidate Master. That same year, he achieved a draw against Grandmaster Paul Keres at the Georgian Chess Championship. He then relocated to Yerevan, where he won both the Armenian Chess Championship and the USSR Junior Chess Championship. Petrosian attained the title of Master during the 1947 USSR Chess Championship, though he did not qualify for the finals. To further improve his game, he intensively studied Nimzowitsch's My System and made the pivotal decision to move to Moscow in 1949, seeking stronger competition and greater opportunities.

3. Chess Career Development

Petrosian's move to Moscow marked a turning point, leading to a rapid ascent through the ranks of Soviet and international chess, culminating in his consistent qualification for top-level competitions and the establishment of his professional career.

3.1. Move to Moscow and Career Advancement

After moving to Moscow in 1949, Petrosian's chess career advanced rapidly, and his results in Soviet events steadily improved. He secured second place in the 1951 Soviet Championship, which earned him the title of International Master. It was during this tournament that Petrosian first encountered the reigning World Champion, Mikhail Botvinnik. Playing with the white pieces, Petrosian found himself in a slightly inferior position after the opening but defended tenaciously through two adjournments and a total of eleven hours of play to achieve a draw.

Petrosian's strong performance in this event qualified him for the Interzonal held the following year in Stockholm. He further distinguished himself by finishing second in the Stockholm tournament, thereby earning the prestigious title of Grandmaster. This achievement also qualified him for the 1953 Candidates Tournament.

3.2. Gaining Grandmaster Title and Early Tournaments

Petrosian placed fifth in the 1953 Candidates Tournament. This result, while respectable, marked the beginning of a period of stagnation in his career. He appeared content with drawing against weaker players and maintaining his Grandmaster title rather than actively striving to improve his game or challenge for the World Championship. This cautious approach was notably illustrated by his performance in the 1955 USSR Championship: out of 19 games played, Petrosian remained undefeated, but he won only four games and drew the remaining fifteen, with many of these draws concluding in twenty moves or fewer.

Although his consistent playing style ensured decent tournament results, it was often criticized by the public and by Soviet chess media and authorities, who viewed it as overly passive. Near the end of the 1955 event, journalist Vasily Panov wrote about the tournament contenders: "Real chances of victory, besides Botvinnik and Smyslov, up to round 15, are held by Geller, Spassky and Taimanov. I deliberately exclude Petrosian from the group, since from the very first rounds the latter has made it clear that he is playing for an easier, but also honourable conquest-a place in the interzonal quartet."

3.3. Soviet Championships and Championship Challenges

The period of complacency in Petrosian's career concluded with the 1957 USSR Championship. In this event, out of 21 games played, Petrosian secured seven wins, suffered four losses, and drew the remaining ten. Although this performance was only sufficient for seventh place in a field of 22 competitors, his more ambitious and dynamic approach to tournament play was met with significant appreciation from the Soviet chess community.

He went on to win his first USSR Championship in 1959. Later that year, in the Candidates Tournament, he defeated Paul Keres, showcasing tactical abilities that were often overlooked given his defensive reputation. Petrosian was awarded the title of Master of Sport of the USSR in 1960 and secured a second Soviet title in 1961. His excellent form continued through 1962, when he qualified for the Candidates Tournament that would lead to his first World Championship match.

4. World Chess Championship

Petrosian's journey to the pinnacle of chess involved a challenging Candidates Tournament, a decisive victory against the reigning champion, a successful title defense, and an eventual loss in a rematch.

4.1. 1963 World Championship

After his strong performance in the 1962 Interzonal in Stockholm, Petrosian qualified for the Candidates Tournament held in Curaçao. The tournament featured a formidable lineup of players including Pal Benko, Miroslav Filip, Bobby Fischer, Efim Geller, Paul Keres, Viktor Korchnoi, and Mikhail Tal. Representing the Soviet Union, Petrosian won the tournament with a final score of 17½ points, closely followed by his Soviet compatriots Geller and Keres, each with 17 points, and the American Fischer with 14 points.

Following the tournament, Fischer publicly accused the Soviet players of arranging draws and conspiring to prevent him from winning. As evidence, he pointed out that all 12 games played between Petrosian, Geller, and Keres resulted in draws. Statisticians further noted that when playing against each other, these Soviet competitors averaged only 19 moves per game, significantly fewer than their average of 39.5 moves when playing against other competitors. While responses to Fischer's allegations were mixed, the FIDE (International Chess Federation) later adjusted its rules and tournament format in an effort to prevent future collusion in the Candidates tournaments.

Having won the Candidates Tournament, Petrosian earned the right to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik for the title of World Chess Champion in a 24-game match. In addition to rigorous chess practice, Petrosian prepared for the match by skiing for several hours each day. He believed that in such a long match, physical fitness and endurance could become a crucial factor in the later games, an advantage amplified by Botvinnik being considerably older than Petrosian. Unlike tournament play where numerous draws could hinder a player from securing first place, draws did not negatively impact the outcome of a one-on-one match. In this regard, Petrosian's cautious playing style was exceptionally well-suited for match play, as it allowed him to patiently await his opponent's mistakes and then capitalize on them. Petrosian won the match against Botvinnik with a final score of 5 wins to 2 losses, with 15 draws, thereby securing the coveted title of World Champion.

4.2. 1966 World Championship

In 1966, three years after he had become World Chess Champion, Petrosian was challenged by Boris Spassky. Petrosian successfully defended his title by winning the match outright, a significant feat that had not been accomplished since Alexander Alekhine defeated Efim Bogoljubov in the 1934 World Championship. This marked a rare instance where a defending champion secured victory without relying on drawing the match to retain the title.

4.3. 1969 World Championship

Despite his loss in 1966, Spassky went on to defeat Efim Geller, Bent Larsen, and Viktor Korchnoi in the subsequent Candidates cycle, earning him a rematch with Petrosian in 1969. The rematch was a hard-fought contest, but Spassky ultimately prevailed with a score of 12½-10½, reclaiming the World Championship title from Petrosian.

5. Later Career and Tournament Participation

After his reign as World Champion, Petrosian continued to be a formidable presence in elite chess, achieving significant tournament results and contributing extensively to the Soviet Union's success in team events.

5.1. Major Tournament Results

Upon becoming World Champion, Petrosian actively campaigned for the publication of a chess newspaper for the entire Soviet Union, rather than one limited to Moscow. This initiative led to the creation of the widely recognized chess magazine 64, of which he later became editor.

In 1976, Petrosian, along with a number of other Soviet chess champions, signed a petition condemning the actions of the defector Viktor Korchnoi. This was a continuation of a bitter feud between the two, which dated back at least to their 1974 Candidates semifinal match. In that match, Petrosian withdrew after five games while trailing 1½-3½ (one win, three losses, one draw). Their subsequent match in 1977 was marked by intense animosity, with both former colleagues refusing to shake hands or speak to each other, and even demanding separate eating and toilet facilities. Petrosian ultimately lost the match to Korchnoi, and as a result, he was fired from his position as editor of 64. His detractors often condemned his reluctance to attack, with some attributing it to a perceived lack of courage. However, Mikhail Botvinnik spoke in his defense, stating that Petrosian only attacked when he felt completely secure, and that his greatest strength lay in his defensive capabilities.

Some of Petrosian's notable successes in his later career included victories at the Lone Pine tournament in 1976 and in the 1979 Paul Keres Memorial tournament in Tallinn, where he scored an impressive 12/16 without a single loss, finishing ahead of strong players like Mikhail Tal and David Bronstein. He shared first place (with Lajos Portisch and Robert Hübner) in the Rio de Janeiro Interzonal in the same year. In 1981, he secured second place in the Tilburg tournament, finishing just half a point behind the winner, Alexander Beliavsky. It was at Tilburg that he played his last famous victory, achieving a miraculous escape against the young and rising star, Garry Kasparov.

5.2. Olympiads and Team Championships

Petrosian was not selected for the Soviet Olympiad team until 1958, despite having already been a World Championship Candidate twice by that time. From 1958 onwards, however, he became a consistent presence, making ten straight Soviet Olympiad teams from 1958 to 1978. During this period, he won an impressive nine team gold medals, one team silver medal, and six individual gold medals. His overall performance in Olympiad play is remarkable: he recorded 78 wins, only 1 loss (to Robert Hübner), and 50 draws out of 129 games played, achieving a winning percentage of 79.8 percent. This places him as the all-time third-best performer in Olympiad history, after Anatoly Karpov (80.1 percent) and Mikhail Tal (81.2 percent).

His Olympiad results are as follows:

| Year | Event | Board | Score | Result | Medals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Munich | 2nd reserve | 10½/13 (+8-0=5) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1960 | Leipzig | 2nd reserve | 12/13 (+11-0=2) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1962 | Varna | 2 | 10/12 (+8-0=4) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1964 | Tel Aviv | 1 | 9½/13 (+6-0=7) | Team Gold | |

| 1966 | Havana | 1 | 11½/13 (+10-0=3) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1968 | Lugano | 1 | 10½/12 (+9-0=3) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1970 | Siegen | 2 | 10/14 (+6-0=8) | Team Gold | |

| 1972 | Skopje | 1 | 10½/16 (+6-1=9) | Team Gold | |

| 1974 | Nice | 4 | 12½/14 (+11-0=3) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1978 | Buenos Aires | 2 | 6/9 (+3-0=6) | Team Silver |

Petrosian also consistently represented the Soviet Union in the first eight European Team Championships, participating from 1957 to 1983. In these events, he secured eight team gold medals and four individual board gold medals. His total record in European Team Championship play stands at 15 wins, 0 losses, and 37 draws, resulting in a 64.4 percent score.

His European Team Championship results are as follows:

| Year | Event | Board | Score | Result | Medals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | Vienna | 6 | 4/5 (+3-0=2) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1961 | Oberhausen | 4 | 6/8 (+4-0=4) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1965 | Hamburg | 1 | 6/10 (+2-0=8) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1970 | Kapfenberg | 1 | 3½/6 (+1-0=5) | Team Gold | |

| 1973 | Bath, Somerset | 2 | 4½/7 (+2-0=5) | Board Gold, Team Gold | |

| 1977 | Moscow | 2 | 3½/6 (+1-0=5) | Team Gold | |

| 1980 | Skara | 3 | 2½/5 (+0-0=5) | Team Gold | |

| 1983 | Plovdiv | 3 | 3½/5 (+2-0=3) | Team Gold |

6. Playing Style and Chess Philosophy

Tigran Petrosian's distinctive approach to chess was characterized by an unparalleled defensive prowess and a deep understanding of positional play, leading to significant contributions to chess theory and strategy.

6.1. Defensive Style and "Iron Tigran"

Petrosian was renowned as a conservative, cautious, and highly defensive chess player, profoundly influenced by Aron Nimzowitsch's concept of prophylaxis. He dedicated more effort to preventing his opponent's offensive capabilities than to initiating his own attacks, and he very rarely went on the offensive unless he felt his position was absolutely secure. His typical strategy involved playing consistently and patiently until an overly aggressive opponent made a mistake, at which point he would capitalize on it without exposing any weaknesses in his own position. This style often resulted in draws, particularly against other players who preferred a counterattacking approach. Nevertheless, his patience and mastery of defense made him exceptionally difficult to defeat. He remained undefeated in the 1952 and 1955 Interzonals, and notably, he did not lose a single tournament game in 1962. Petrosian's consistent ability to avoid defeat earned him the enduring nickname "Iron Tigran." Authors of a 2004 book considered him to be the hardest player to beat in the history of chess, and future World Champion Vladimir Kramnik famously called him "the first defender with a capital D."

Petrosian preferred to play closed openings that did not commit his pieces to any specific plan prematurely. As Black, he favored the Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation and the French Defence. As White, he frequently employed the English Opening. Petrosian would often move the same piece multiple times within a few moves, a tactic that could confuse his opponents in the opening and even threaten draws by threefold repetition in the endgame. In a notable game against Mark Taimanov during the 1955 USSR Chess Championship, Petrosian moved the same rook six times in a 24-move game, with four of those moves occurring on consecutive turns. He also displayed a strong affinity for knights over bishops, a characteristic frequently attributed to the influence of Aron Nimzowitsch.

Numerous illustrative metaphors have been used to describe Petrosian's unique style of play. Harold C. Schonberg famously remarked that "playing him was like trying to put handcuffs on an eel. There was nothing to grip." He has also been described as a centipede lurking in the dark, a tiger patiently awaiting the opportunity to pounce, a python slowly squeezing its victims to death, and as a crocodile that waits for hours to make a decisive strike. Boris Spassky, who succeeded Petrosian as World Chess Champion, aptly described his style: "Petrosian reminds me of a hedgehog. Just when you think you have caught him, he puts out his quills." Bobby Fischer, another World Champion, also noted Petrosian's incredible defensive foresight: "He [Petrosian] has incredible tactical vision, and a great ability to judge danger... No matter how good you think, calculate... He will 'smell' any danger 20 moves ahead!"

While highly successful for avoiding defeats, Petrosian's playing style was sometimes criticized for being dull. Chess enthusiasts viewed his "ultraconservative" approach as an unwelcome contrast to the popular image of Soviet chess as "daring" and "indomitable." For instance, his 1971 Candidates Tournament match with Viktor Korchnoi featured so many monotonous draws that the Russian press began to openly complain. However, Svetozar Gligorić praised Petrosian for being "very impressive in his incomparable ability to foresee danger on the board and to avoid any risk of defeat." Petrosian himself responded to his critics by saying: "They say my games should be more 'interesting'. I could be more 'interesting'-and also lose." A consequence of Petrosian's style was that he did not score many outright victories, which meant he seldom won tournaments, even though he frequently finished in second or third place. Nevertheless, his style proved exceptionally effective in match play. Petrosian could also occasionally surprise opponents with an attacking, sacrificial style. In his 1966 match with Spassky, he won Game 7 and Game 10 in this manner. Boris Spassky later commented: "It is to Petrosian's advantage that his opponents never know when he is suddenly going to play like Mikhail Tal." (Tal was widely known as the most aggressive attacker of his era.)

6.2. Major Chess Contributions

Petrosian was particularly known for his innovative use of the "positional exchange sacrifice", a strategic concept where one side sacrifices a rook for the opponent's bishop or knight. Garry Kasparov elaborated on Petrosian's mastery of this motif, stating that "Petrosian introduced the exchange sacrifice for the sake of 'quality of position', where the time factor, which is so important in the play of Alekhine and Tal, plays hardly any role. Even today, very few players can operate confidently at the board with such abstract concepts. Before Petrosian no one had studied this. By sacrificing the exchange 'just like that', for certain long term advantages, in positions with disrupted material balance, he discovered latent resources that few were capable of seeing and properly evaluating."

A famous illustration of Petrosian's positional exchange sacrifice comes from his game against Samuel Reshevsky in Zurich in 1953. In the position after 25.Rfe1, Reshevsky, playing White, appeared to have an advantage due to his strong pawn centre, which could become mobile after Bf3 and d4-d5. Petrosian recognized he was in a difficult position due to the passive placement of his pieces, relegated to defensive roles. He further understood that White might also advance on the kingside with h2-h4-h5, provoking weaknesses that would make defense more difficult later. Faced with these threats, Petrosian devised a plan to maneuver his knight to the square d5, where it would be prominently placed in the center and blockade the advance of White's pawns.

:25... Re6!

With the rook vacated from e7, the black knight is now free to move to d5, where it will attack the pawn on c3 and help support an eventual advance of Black's queenside pawn majority with ...b5-b4.

:26. a4 Ne7 27. Bxe6 fxe6 28. Qf1 Nd5 29. Rf3 Bd3 30. Rxd3 cxd3

The game eventually concluded in a draw on move 41.

Petrosian also made significant contributions to opening theory. He was an expert against the King's Indian Defence, and he frequently played what is now known as the Petrosian System: 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 Bg7 4.e4 d6 5.Nf3 0-0 6.Be2 e5 7.d5. This variation closes the center early in the game. One of the tactical ideas for White is to play Bg5, pinning Black's knight to the queen. Black can respond by either moving the queen (usually ...Qe8) or by playing ...h6, though the latter move weakens Black's kingside pawn structure. Two of Black's common responses to the Petrosian Variation were developed by grandmasters Paul Keres and Leonid Stein. The Keres Variation arises after 7...Nbd7 8.Bg5 h6 9.Bh4 g5 10.Bg3 Nh5 11.h4, while the Stein Variation initiates an immediate queenside offensive with 7...a5.

The Queen's Indian Defence also features a variation developed by Petrosian: 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 b6 4.a3, with the primary idea of preventing Black's ...Bb4+ move. This system gained considerable attention in 1980 when it was successfully employed by the young Garry Kasparov to defeat several grandmasters. Today, the Petrosian Variation in the Queen's Indian Defence is still considered a highly pressing variation, with a strong scoring record in master games.

Other Petrosian variations can be found in the Grünfeld Defence after 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Bg5, and the French Defence after 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 Qd7. Some authorities also refer to a variation of the Caro-Kann Defence by his name, along with former world champion Vasily Smyslov: the Petrosian-Smyslov Variation, which begins with 1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Nd7.

7. Personal Life and Health

Beyond the chess board, Tigran Petrosian led a rich personal life, marked by family connections, enduring health challenges, and a variety of interests that provided balance to his competitive career.

7.1. Marriage and Family

Petrosian resided in Moscow from 1949 onwards, living at 59 Pyatnitskaya Street during the 1960s and 1970s. When asked by Anthony Saidy if he considered himself Russian, Petrosian responded: "Abroad, they call us all Russians. I am a Soviet Armenian."

In 1952, Petrosian married Rona Yakovlevna (née Avinezer, 1923-2005), a Russian Jew born in Kiev, Ukraine. Rona was a graduate of the Moscow Institute of Foreign Languages and worked as an English teacher and interpreter. She is buried in the Jewish section of the Vostryakovsky cemetery in Moscow. Tigran and Rona had two sons: Vartan and Mikhail. Mikhail was Rona's son from a previous marriage whom Tigran adopted.

7.2. Hearing Impairment

Petrosian was partially deaf and wore a hearing aid during his matches, which occasionally led to unusual situations. On one occasion, he offered a draw to Svetozar Gligorić. Gligorić initially refused in surprise but then changed his mind within a few seconds and re-offered the draw. Petrosian, however, did not respond to the renewed offer and eventually went on to win the game. It was later discovered that he had switched off his hearing aid and simply did not hear Gligorić's second offer. In 1971, he played a Candidates match against Robert Hübner in a noisy area in Seville. While the noise did not disturb Petrosian, it so frustrated Hübner that he ultimately withdrew from the match. Despite his hearing difficulties, Petrosian was a great admirer of classical music and enjoyed attending concerts.

7.3. Hobbies and Interests

Outside of the competitive chess arena, Petrosian engaged in a variety of personal interests and hobbies. These included football, backgammon, cross-country skiing, table tennis, and gardening.

8. Death and Legacy

Tigran Petrosian's passing marked the end of an era for a chess legend, but his influence and memory continue to resonate deeply within the chess world and particularly in his homeland, Armenia.

8.1. Death

Tigran Petrosian died in Moscow of stomach cancer on August 13, 1984, at the age of 55. He is buried in the Moscow Armenian Cemetery.

8.2. Commemoration and Influence

At the time of his death, Petrosian was actively working on a collection of chess-related lectures and articles intended for publication in a book. These works were subsequently edited by his wife, Rona, and published posthumously in Russian under the title Шахматные лекции Петросяна (1989) and in English as Petrosian's Legacy (1990).

In 1987, World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov unveiled a memorial at Petrosian's grave. This memorial features a laurel wreath, symbolizing the award given to Chess World Champions, and an image within a crown depicting the sun shining above the twin peaks of Mount Ararat, the national symbol of Petrosian's Armenian homeland. On July 7, 2006, a monument honoring Petrosian was officially opened in the Davtashen district of Yerevan, located on the street named after him.

Petrosian's image has also been featured on the third banknote series of the Armenian dram, specifically on the 2.00 K AMD banknote, further solidifying his cultural legacy and recognition in Armenia. He is widely credited with popularizing chess in Armenia, where the sport holds a significant cultural status.

9. Criticism and Controversy

Throughout his career, Tigran Petrosian faced various criticisms regarding his playing style, as well as involvement in allegations of collusion during tournaments and a notable personal feud with a fellow grandmaster.

His playing style, while highly effective in preventing losses, was often deemed "dull" or "ultraconservative" by some chess enthusiasts and Soviet media, who contrasted it with the more "daring" image of Soviet chess. This criticism was particularly vocal during his 1971 Candidates match against Viktor Korchnoi, which featured numerous draws. Petrosian famously responded to such critiques by stating, "They say my games should be more 'interesting'. I could be more 'interesting'-and also lose." More details on his playing style and its reception can be found in the "Defensive Style and 'Iron Tigran'" section.

A significant controversy arose during the 1962 Candidates Tournament in Curaçao, where Petrosian emerged victorious. Following the tournament, Bobby Fischer accused the Soviet players, including Petrosian, of colluding by arranging short draws among themselves to prevent him from winning. Statistical analysis showed that games between Petrosian, Efim Geller, and Paul Keres averaged significantly fewer moves than their games against other competitors. While the accusations were met with mixed reactions, the FIDE (International Chess Federation) later adjusted its rules and tournament format to prevent similar situations in the future. This incident is detailed further in the "1963 World Championship" section.

Petrosian was also involved in a bitter and public feud with Viktor Korchnoi, which intensified after Korchnoi's defection from the Soviet Union in 1976. The animosity between them was evident in their 1974 Candidates semifinal match, from which Petrosian withdrew while trailing, and particularly in their 1977 match, where they notably refused to shake hands or speak, even demanding separate facilities. This rivalry and its consequences, including Petrosian's dismissal from his editorial position at 64, are elaborated upon in the "Major Tournament Results" section.