1. Overview

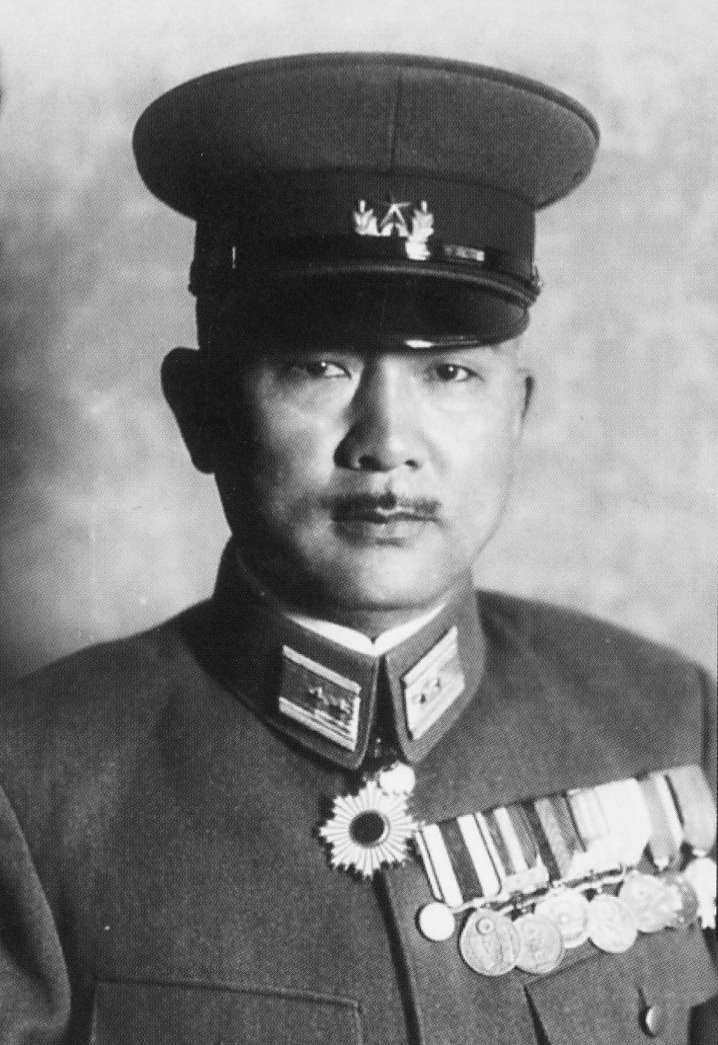

Tadamichi Kuribayashi was a highly skilled general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, best known for his command of the Japanese garrison during the Battle of Iwo Jima. Born into a traditional samurai family in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, Kuribayashi pursued a military career after initially considering journalism. His early diplomatic assignments in Canada and the United States provided him with a unique understanding of American industrial power, leading him to express caution about war with the United States.

Appointed to defend Iwo Jima in 1944, Kuribayashi recognized the island's strategic importance and the overwhelming numerical and material superiority of the United States Armed Forces. He devised an innovative defense strategy that departed significantly from conventional Japanese tactics, emphasizing a prolonged attrition warfare from extensive underground fortifications rather than suicidal banzai charges or water's edge defenses. His meticulous planning and leadership enabled his forces to hold out for 36 days against a much larger American invasion, inflicting severe casualties and earning the grudging respect of his adversaries.

Kuribayashi's command at Iwo Jima is noted for his dedication to his soldiers' lives, his strict discipline, and his personal commitment to sharing their hardships. His leadership during the brutal battle, characterized by dwindling resources and a desperate final stand, highlighted the immense human cost of the conflict. He was posthumously promoted to General and is believed to have been killed in action while leading a final assault, though his body was never identified. Post-war assessments, particularly from American military leaders, have lauded his strategic genius and tenacity, cementing his legacy as one of the most formidable commanders of the Pacific War. His personal life, revealed through his letters to his family, also portrays him as a devoted husband and father with a talent for writing and poetry.

2. Early Life and Background

Tadamichi Kuribayashi was born on July 7, 1891, in Matsushiro, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. His family was an established samurai lineage tracing back to the Sengoku period, having served as land-owning nobles under the Sanada clan and later as members of the Matsushiro Domain during the Edo period. In the Meiji period, the family attempted ventures in silk and banking, both of which failed due to their aristocratic status. By the time of Kuribayashi's birth, his family was working to rebuild their estate after fires destroyed their property in 1868 and 1881. His father, Tsurujiro, worked in lumber and civil engineering, while his mother, Moto, maintained the family farm.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Kuribayashi attended Matsushiro Higher Elementary School and then Nagano Middle School (now Nagano High School), where he excelled academically, particularly in the English language. He initially harbored aspirations of becoming a foreign correspondent, a desire he later mentioned to a reporter while stationed on Iwo Jima during World War II. Vice Admiral Shigeji Kaneko, a classmate from Nagano, recalled Kuribayashi's early literary talents, noting that he was "already good in poetry-writing, composition and speech-making" and was "a young literary enthusiast." Kaneko also recounted an incident where Kuribayashi "once organized a strike against the school authorities" and "just escaped expulsion by a hair."

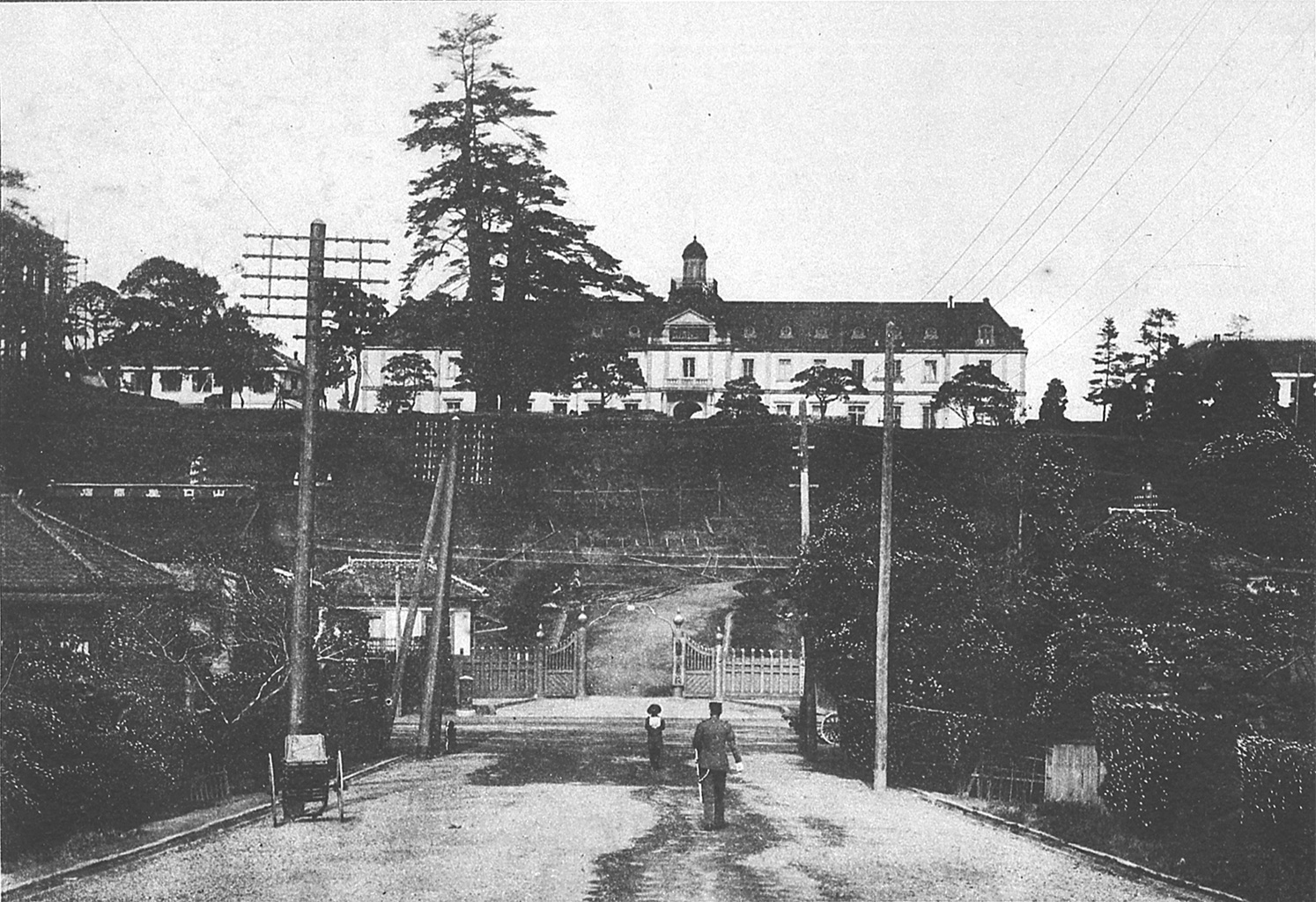

As a student, Kuribayashi passed entrance examinations for both Tōa Dōbun Shoin, a prestigious Japanese college in Shanghai, and the Imperial Japanese Army Academy, ultimately choosing the latter. He matriculated into the Army Academy as a member of its 26th class in December 1912, specializing in cavalry. After being commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in December 1911 and promoted to First Lieutenant in July 1918, he attended the Army War College in Minato, Tokyo, for advanced command training from December 1920. He graduated second in his class in November 1923, as part of the 35th class. As a recognition of his high academic achievement, he was presented with a guntō (military sword) by the Emperor Taishō and earned the unique privilege to study abroad.

Kuribayashi chose to study alone in the United States as a military attaché with the 1st Cavalry Division, a choice that contrasted with most students who opted for places like Germany or France. He departed Japan in March 1928 as a 36-year-old cavalry captain and resided with a local family in Buffalo, New York. His experience in the United States would significantly distinguish him from other generals in the Imperial Japanese Army. He enrolled in Harvard University, completing courses in English, American history, and American politics, and also audited similar courses at the University of Michigan. During his time in the country, Kuribayashi traveled extensively, living in Washington, D.C., Boston, Fort Bliss, Texas, and Fort Riley, Kansas, and visiting New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. He purchased a Chevrolet automobile and learned to drive from an American officer, using the car to journey across the country. While training with the U.S. Army at Fort Riley, Kuribayashi befriended Brigadier General George Van Horn Moseley. He later recalled his observations from this period: "I was in the United States for three years when I was a captain. I was taught how to drive by some American officers, and I bought a car. I went around the States, and I knew the close connections between the military and industry. I saw the plant area of Detroit, too. By one button push, all the industries will be mobilized for military business."

2.2. Family Life

Kuribayashi married Yoshii Kuribayashi (1904-2003) on December 8, 1923. Although Yoshii's maiden name was also Kuribayashi, there was no direct blood relation between them. She was the daughter of a landlord from the Kawakanajima area, now Hinoki, Nagano. Together, they had a son, Taro, and two daughters, Yoko and Takako. His grandson, through his daughter Takako, is Yoshitaka Shindō, a member of the House of Representatives. Kuribayashi was known as a devoted family man, always striving to spend as much time as possible with his family and maintaining regular communication with them, even from afar during his military assignments.

3. Military and Diplomatic Career

Kuribayashi's military career saw him rise steadily through the ranks of the Imperial Japanese Army, interspersed with important diplomatic postings that shaped his views on international relations and military strategy.

3.1. Early Military Service

After graduating from the Army Academy, Kuribayashi was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the cavalry in December 1911. He specialized in cavalry, attending the Army's Cavalry School from October 1917 to July 1918. He was promoted to First Lieutenant in July 1918 and to Captain in August 1923. His early assignments included serving as a company commander in the 15th Cavalry Regiment and as a member of the Cavalry Inspectorate. He was promoted to Major in March 1930 and to Lieutenant Colonel in August 1933. In August 1936, he took command of the 7th Cavalry Regiment.

3.2. Diplomatic Assignments

Kuribayashi's diplomatic career began in 1927 when he was posted as an assistant military attaché to the Japanese Embassy in the United States. During this period, he also studied at Harvard University. After returning to Japan in March 1930, he was appointed as the first Japanese military attaché to Canada in August 1931, serving at the Japanese Legation in Canada.

His two years in the United States were particularly formative. He traveled extensively across the country, interacting not only with American military personnel but also with ordinary citizens, developing a deep understanding of American society and industry. He found Americans to be "cheerful and friendly people." His observations led him to a cautious view on the prospect of war with the United States. He frequently expressed to his wife, Yoshii, that "America is the last country in the world Japan should fight," emphasizing that "its industrial power is great, and its people are diligent. Japan should avoid fighting this country as much as possible. Never underestimate American strength." These views were controversial among some Japanese military circles at the time, which often underestimated American capabilities.

3.3. Pre-War Service

From 1933 to 1937, Kuribayashi served in the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff in Tokyo. During this period, he showcased his literary talent by writing lyrics for several martial songs, including his contribution to the selection of the popular military song Aiba Shingunka (Cavalry Marching Song) in 1938. In August 1937, he was promoted to Colonel and became the head of the Horse Administration Department in the Army Ministry's Military Affairs Bureau. He was further promoted to Major General in March 1940, taking command of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, and then the 1st Cavalry Brigade in December 1940. Leading up to the Attack on Pearl Harbor, Kuribayashi is known to have repeatedly told his family, "America is the last country in the world Japan should fight."

4. Pacific War Service

Kuribayashi's involvement in the Pacific War began with key roles in major campaigns, leading to his ultimate command at Iwo Jima.

4.1. Chief of Staff, 23rd Army

In December 1941, at the outset of the Pacific War, Kuribayashi was ordered into the field as the Chief of Staff of the Japanese 23rd Army, commanded by Takashi Sakai. The 23rd Army's primary mission in the initial Southern Operation was the invasion of British-held Hong Kong. Following the declaration of war on December 8, the 23rd Army swiftly defeated the British forces in the Battle of Hong Kong within 18 days, securing control of the territory. The subsequent occupation by the 23rd Army led to horrific massacres in Hong Kong. After the war, Takashi Sakai, the 23rd Army's commander, was accused of war crimes by the Chinese War Crimes Military Tribunal, found guilty, and executed by firing squad on September 30, 1946. Despite the grim context of these operations, Kuribayashi was noted for his unusual dedication to his men; a former subordinate recalled that Kuribayashi regularly visited wounded enlisted men in the hospital, a practice virtually unheard of for an officer of the General Staff.

4.2. Commander, 2nd Guards Division

In June 1943, Kuribayashi was promoted to Lieutenant General and reassigned as the commander of the 2nd Imperial Guards Division. This division primarily served as a reserve and training unit within Japan.

4.3. Commander, 109th Division and Ogasawara Defense

On May 27, 1944, Kuribayashi was appointed commander of the newly formed 109th Division, specifically tasked with the defense of the Ogasawara Islands. Just two weeks later, on June 8, 1944, he received direct orders, signed by Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, to defend the strategically vital island of Iwo Jima within the Bonin Islands chain. Upon receiving these orders, his wife, Yoshii Kuribayashi, recalled that her husband remarked it was unlikely even his ashes would return from Iwo Jima.

According to historian Kumiko Kakehashi, it is possible that Kuribayashi was deliberately chosen for what was widely understood to be a suicide mission. General Kuribayashi was known for having expressed the belief that Japan's war against the United States was a no win situation and needed to be concluded through a negotiated peace. In the eyes of the ultra-nationalists within the General Staff and Tojo's cabinet, this perspective allegedly led Kuribayashi to be viewed as a defeatist. Despite this, he was accorded the rare honor of a personal audience with Emperor Hirohito on the eve of his departure. However, in a subsequent letter to Yoshii and their children, the General made no mention of meeting the Emperor. Instead, he expressed regret for failing to fix a draft in their home's kitchen and included a detailed diagram for his son, Taro Kuribayashi, to complete the repair, hoping to prevent the family from catching cold.

5. Battle of Iwo Jima

The Battle of Iwo Jima stands as a testament to Kuribayashi's strategic acumen and the fierce determination of the Japanese defenders under his command.

5.1. Appointment and Strategic Planning

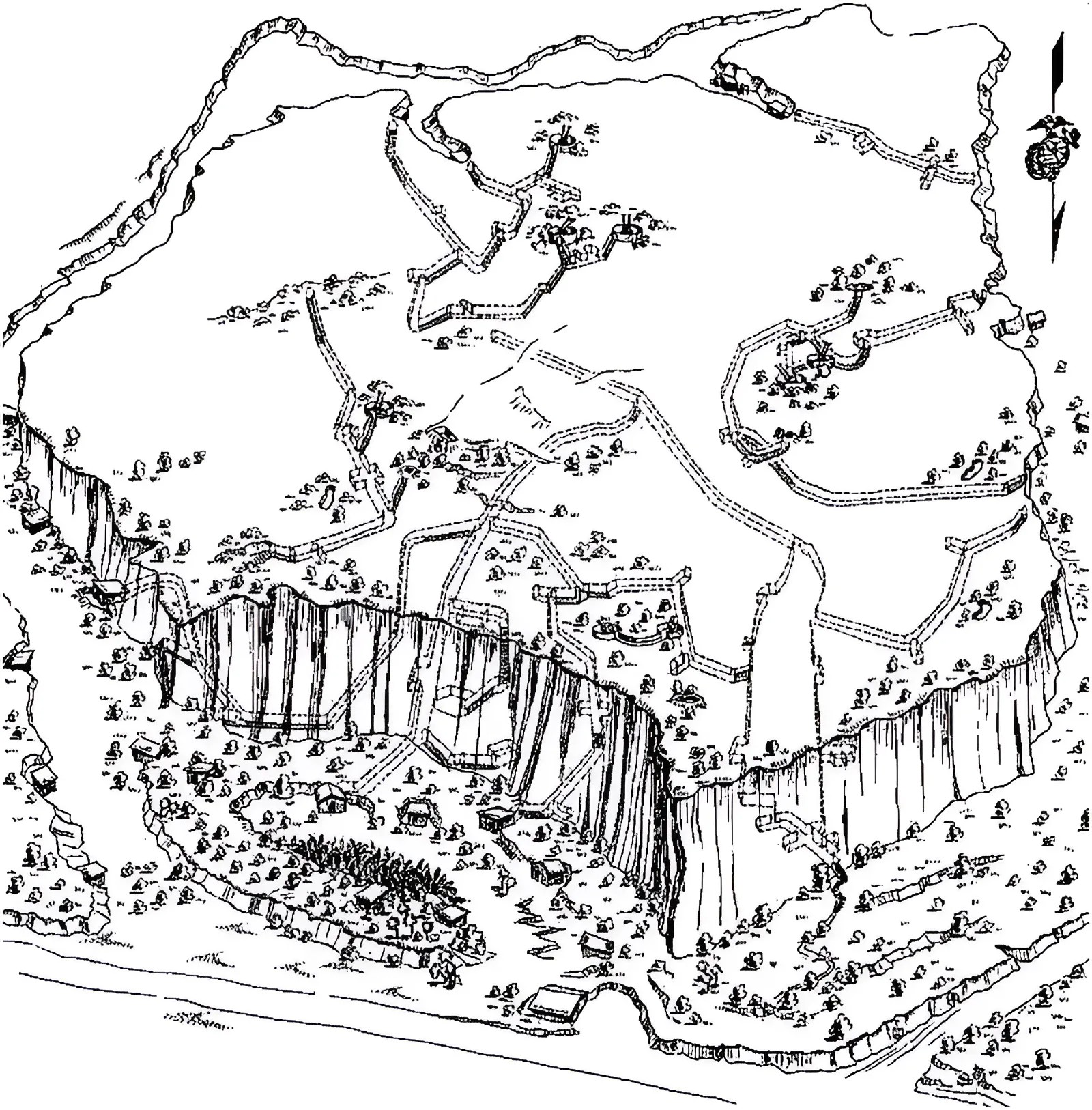

General Kuribayashi arrived on Iwo Jima on June 19, 1944, stepping off a plane at the Chidori airstrip. At the time, the island's garrison was busy digging trenches along the beaches, adhering to the conventional "water's edge defense" strategy. Kuribayashi, however, conducted a thorough survey of the island and immediately issued orders to construct defenses further inland. He made the radical decision not to seriously contest the projected beach landings, decreeing that the defense of Iwo Jima would be fought almost entirely from underground. His men subsequently honeycombed the island with over 11 mile (18 km) of tunnels, 5,000 caves, and pillboxes. His former Chief of Staff recalled Kuribayashi's stark assessment: "America's productive powers are beyond our imagination. Japan has started a war with a formidable enemy and we must brace ourselves accordingly."

Kuribayashi recognized that he would not be able to hold Iwo Jima indefinitely against the overwhelming military forces of the United States. He understood that the loss of Iwo Jima would bring all of Japan within range of American strategic bombers. Therefore, he planned a campaign of attrition, by which he hoped to delay the bombing of Japanese civilians and to force the United States Government to reconsider the possible invasion of the Japanese home islands. Historian James Bradley noted, "Americans have always taken casualties very seriously. When the number of casualties is too high, public opinion will boil up and condemn an operation as a failure, even if we get the upper hand militarily. Kuribayashi had lived in America. He knew our national character. That's why he deliberately chose to fight in a way that would relentlessly drive up the number of casualties. I think he hoped American public opinion would shift toward wanting to bring the war with Japan to a rapid end."

Long before the Americans landed, General Kuribayashi fully expected to die on Iwo Jima. On September 5, 1944, he wrote to his wife, "It must be destiny that we as a family must face this. Please accept this and stand tall with the children at your side. I will be with you always." The harsh conditions on the island were evident in his letters; Private Takeo Abe, a survivor, later recalled, "By the end of 1944, we were forced to spare rations for battle and we foraged around for edible weeds. Suffering from chronic diarrhea, empty stomachs, and lack of water, we dug bunkers in the sand under a merciless sun and constructed underground shelters that were steamy with heat. We used salt water, lukewarm from a well on the beach, for cooking, and saved what little rainwater we could for drinking. But one water-bottle a day was the most we ever had to drink." In a letter dated June 25, 1944, Kuribayashi wrote, "There is no springwater here, so we must do with rainwater. I long for a glass of cold water, but nothing can be done. The number of flies and mosquitoes is appalling. There are no newspapers, no radios, and no shops... It is a living hell and I have never experienced anything remotely like it in my entire life."

5.2. Defensive Tactics and Leadership

To prepare his soldiers for an unconventional style of fighting, Kuribayashi composed six "Courageous Battle Vows" which were widely reproduced and distributed among his men:

- We shall defend this island with all our strength to the end.

- We shall fling ourselves against the enemy tanks clutching explosives to destroy them.

- We shall slaughter the enemy, dashing in among them to kill them.

- Every one of our shots shall be on target and kill the enemy.

- We shall not die until we have killed ten of the enemy.

- We shall continue to harass the enemy with guerrilla tactics even if only one of us remains alive.

Kuribayashi also composed a set of detailed instructions to the soldiers of the "Courage Division," emphasizing strategic defense over reckless charges:

- Preparations for battle.**

- Use every moment you have, whether during air raids or during battle, to build strong positions that enable you to smash the enemy at a ratio of ten to one.

- Build fortifications that enable you to shoot and attack in any direction without pausing even if your comrades should fall.

- Be resolute and make rapid preparations to store food and water in your position so that your supplies will last even through intense barrages.

- Fighting defensively.**

- Destroy the American devils with heavy fire. Improve your aim and try to hit your target the first time.

- As we practiced, refrain from reckless charges, but take advantage of the moment when you've smashed the enemy. Watch out for bullets from others of the enemy.

- When one man dies a hole opens up in your defense. Exploit man-made structures and natural features for your own protection. Take care with camouflage and cover.

- Destroy enemy tanks with explosives, and several enemy soldiers along with the tank. This is your best chance for meritorious deeds.

- Do not be alarmed should tanks come toward you with a thunderous rumble. Shoot at them with anti-tank fire and use tanks.

- Do not be afraid if the enemy penetrates inside your position. Resist stubbornly and shoot them dead.

- Control is difficult to exercise if you are sparsely dispersed over a wide area. Always tell the officers in charge when you move forward.

- Even if your commanding officer falls, continue defending your position, by yourself if necessary. Your most important duty is to perform brave deeds.

- Do not think about eating and drinking, but focus on exterminating the enemy. Be brave, O warriors, even if rest and sleep are impossible.

- The strength of each of you is the cause of our victory. Soldiers of the Courage Division, do not crack at the harshness of the battle and try to hasten your death.

- We will finally prevail if you make the effort to kill just one man more. Die after killing ten men and yours is a glorious death on the battlefield.

- Keep on fighting even if you are wounded in the battle. Do not get taken prisoner. At the end, stab the enemy as he stabs you.

Kuribayashi strictly forbade banzai charges, which he regarded as an unnecessary waste of his men's lives, a significant departure from common Japanese military doctrine. He also resisted the traditional "water's edge defense" strategy, learning from the failures of previous island battles like Saipan and Peleliu. He even ordered the tanks of the 26th Tank Regiment, commanded by Takeichi Nishi, to be buried in holes or concealed in depressions, with only their turrets exposed, to serve as defensive pillboxes. Nishi, a fellow cavalry officer, initially resisted this order, preferring mobile tank warfare, but ultimately complied. While some accounts suggest a close relationship between Kuribayashi and Nishi, others point to a potential friction due to their contrasting personalities-Kuribayashi being diligent and sensitive, while Nishi, a baron from a wealthy family, was more unrestrained.

Lieutenant Colonel Baron Takeichi Nishi, commander of the 26th Tank Regiment on Iwo Jima Kuribayashi paid particular attention to the welfare and morale of his soldiers, especially given the brutal conditions they would face. He conducted daily inspections of the island, not only to check the status of fortifications but also to gauge troop morale and ensure officers treated their men properly. He enforced a strict rule that salutes were unnecessary during work or training and did not hesitate to punish officers if complaints from soldiers were substantiated. Crucially, he strictly forbade officers, including himself, from eating more lavish meals than the enlisted men. He ate the same coarse food and used the same limited amount of water as his soldiers, recognizing that "food resentment" was a significant issue in the military and could severely undermine trust and fighting capability, especially in a resource-scarce environment like Iwo Jima. This personal commitment deeply impressed his troops and fostered strong loyalty. Furthermore, Kuribayashi ensured the early evacuation of Iwo Jima's civilian population, which numbered around 1,000, by July 1944. He also took measures to prevent sexual harassment, requesting women to wear monpe (traditional Japanese work pants) and, where possible, separating military and civilian shelters.

5.3. The Battle

The Battle of Iwo Jima commenced on February 16, 1945, with a fierce pre-landing naval and aerial bombardment by American forces. On February 19, at 9:00 AM, the first wave of Marine Corps troops landed on the southern shore of the island. In a radical departure from expected Japanese tactics, Kuribayashi allowed the American officers and men to land largely unmolested before unleashing devastating fire from his underground bunkers. As night fell, Marine Corps General Holland Smith, aboard the command ship USS Eldorado, was particularly astonished that Kuribayashi's men had not attempted a banzai charge. Addressing war correspondents, he quipped, "I don't know who he is, but the Japanese General running this show is one smart bastard."

Despite Kuribayashi's orders, some Japanese naval coastal artillery and Mt. Suribachi's guns prematurely engaged the landing forces. Kuribayashi quickly re-emphasized his directive to hold fire, but the damage was done; the US forces identified these positions and systematically destroyed them with an 11-hour naval bombardment, an action later described as "Kuribayashi's only tactical error" in the official US Marine Corps history of the battle. However, after 10:00 AM, the Japanese forces, adhering to Kuribayashi's plan, launched a coordinated, devastating attack once the American landing force had advanced sufficiently inland. The 4th Marine Division's battle report praised the Japanese forces' "skillful artillery command" as having "a cleverness that no military genius had ever conceived." The Americans, who initially believed the commander to be Major General Ohsuga, the Ogasawara Fortress Commander, learned from captured Japanese soldiers that "Lieutenant General Kuribayashi" was the supreme commander. This revelation, coupled with reports of a larger-than-expected Japanese force, raised concerns among American commanders who realized they faced a formidable and skilled tactician.

The battle continued with relentless intensity. On March 7, Kuribayashi sent his last battle report, "Tan San Den No. 351," to the Imperial Headquarters and to General Ban Hasunuma, his former instructor and a senior cavalry officer. By March 16, at 4:00 PM, with organized resistance nearing its end, Kuribayashi sent a farewell telegram, signifying gyokusai (honorable death), to the Imperial Headquarters.

5.4. Final Resistance

On March 17, 1945, Kuribayashi was officially declared killed in action and was posthumously promoted to the rank of General by special Imperial decree. This promotion was granted despite him not meeting the typical two-and-a-half-year command requirement for posthumous promotion to General, a testament to his exceptional merit. On the same day, he sent his farewell message to Imperial Headquarters, accompanied by three traditional waka poems. According to historian Kumiko Kakehashi, these poems were "a subtle protest against the military command that so casually sent men out to die."

His final message read: "The battle is entering its final chapter. Since the enemy's landing, the gallant fighting of the men under my command has been such that even the gods would weep. In particular, I humbly rejoice in the fact that they have continued to fight bravely though utterly empty-handed and ill-equipped against a land, sea, and air attack of a material superiority such as surpasses the imagination. One after another they are falling in the ceaseless and ferocious attacks of the enemy. For this reason, the situation has arisen whereby I must disappoint your expectations and yield this important place to the hands of the enemy. With humility and sincerity, I offer my repeated apologies. Our ammunition is gone and our water dried up. Now is the time for us to make the final counterattack and fight gallantly, conscious of the Emperor's favor, not begrudging our efforts though they turn our bones to powder and pulverize our bodies. I believe that until the island is recaptured, the Emperor's domain will be eternally insecure. I therefore swear that even when I have become a ghost I shall look forward to turning the defeat of the Imperial Army to victory. I stand now at the beginning of the end. At the same time as revealing my inmost feelings, I pray earnestly for the unfailing victory and security of the Empire. Farewell for all eternity."

He closed the message with his three waka poems:

:Unable to complete this heavy task for our country

:Arrows and bullets all spent, so sad we fall.

:But unless I smite the enemy,

:My body cannot rot in the field.

:Yea, I shall be born again seven times

:And grasp the sword in my hand.

:When ugly weeds cover this island,

:My sole thought shall be the Imperial Land.

(The first poem's line "so sad we fall" was infamously changed to "so regrettable" by the Imperial Headquarters for public release in newspapers.)

On the evening of March 23, 1945, Kuribayashi radioed a last message to Major Yoshitaka Hori, who commanded the radio station on Chichi-jima: "All officers and men of Chichi Jima - goodbye from Iwo." Major Hori later recalled trying to communicate with them for three days after that, but received no answer. Another message from March 23 stated, "We have not eaten or drunk for five days, but the Yamato spirit, our fighting spirit, is still high; we will fight to the last moment."

Meanwhile, General Kuribayashi had gathered the remnants of the Iwo Jima garrisons into a heavily fortified ravine dubbed "The Gorge" by the Marine Corps. Major Hori recalled that "General Kuribayashi commanded his battle under candle light without a single rest or sleep, day after day." Marine Corps General Graves B. Erskine sent Japanese American Marines and captured Japanese soldiers to try to persuade Kuribayashi and his men to surrender. Kuribayashi radioed to Major Hori, "I have 400 men under my command. The enemy besieged us by firing and flame from their tanks. In particular, they are trying to approach the entrance of our cave with explosives. My men and officers are still fighting. The enemy's front lines are 984 ft (300 m) from us, and they are attacking by tank firing. They advised us to surrender by loudspeaker, but we only laughed at this childish trick, and we did not set ourselves against them."

6. Death

The exact circumstances surrounding General Kuribayashi's death remain a mystery, as his body was never identified by the United States military.

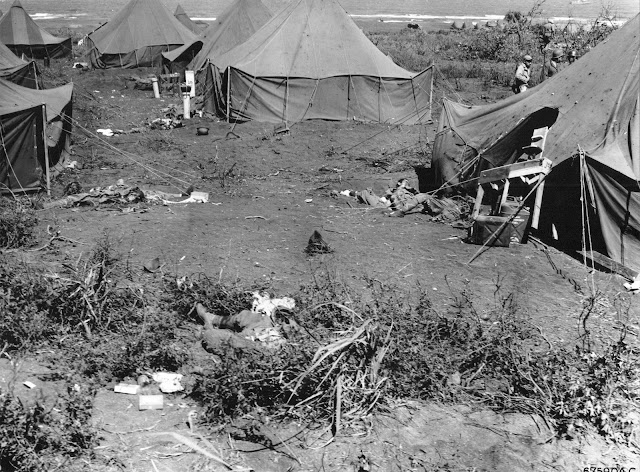

It is most likely that he was killed in action in the early morning of March 26, 1945, while leading his surviving soldiers in a three-pronged assault against sleeping Marines and Air Force ground crews. This attack, which began at 5:15 AM, targeted the bivouac areas of the 7th Fighter Group and the 5th Engineer Battalion near the western coast of the island. Kuribayashi and his men silently slashed tents, bayoneted sleeping personnel, and lobbed hand grenades. According to the official United States Marine Corps History, "The Japanese attack on the early morning of 26 March was not a banzai charge, but an excellent plan aiming to cause maximum confusion and destruction." The assault climaxed in a ferocious hand-to-hand battle. The Japanese attacking force was heavily armed with both Japanese and captured American weapons, including bazookas and automatic rifles. The presence of 40 officers carrying swords indicated a high proportion of senior officers among the attackers. The battle lasted for three hours, resulting in 44 fighter pilots killed and 88 wounded, along with 9 Marines killed and 31 wounded. Kuribayashi's body could not be identified afterwards because he had removed all officer's insignia in order to fight as a regular soldier.

Less credible theories suggest that Kuribayashi committed seppuku at his headquarters in the Gorge. However, these accounts lack direct eyewitness testimony.

His son, Taro Kuribayashi, interviewed several survivors of the Japanese garrison after the war. Based on these accounts, he believes that his father was killed in an artillery barrage during the final assault. According to Taro Kuribayashi, "My father had believed it shameful to have his body discovered by the enemy even after death, so he had previously asked his two soldiers to come along with him, one in front and the other behind, with a shovel in hand. In case of his death, he had wanted them to bury his body there and then. It seems that my father and the soldiers were killed by shells, and he was buried at the foot of a tree in Chidori village, along the beach near Osaka mountain. Afterwards, General Smith spent a whole day looking for his body to pay respect accordingly and to perform a burial, but in vain." Other theories include that he was wounded by enemy fire, bled to death, and was buried by his Chief of Staff, or that his body was completely disintegrated by a direct hit from a 6.1 in (155 mm) artillery shell. After the final assault, 262 Japanese bodies were found, and 18 were taken prisoner. Despite efforts by the Marine Corps to locate his remains out of respect, Kuribayashi's body was never found.

7. Post-War Assessment and Legacy

The United States declared Iwo Jima secure on March 26, 1945. The battle resulted in significant casualties for both sides. The US suffered 26,039 casualties, including 6,821 killed and 19,189 wounded. Of the approximately 22,786 Japanese defenders, only 1,083 survived to be captured, with 20,703 dying in combat or by suicide. A small number of Japanese holdouts continued to resist, emerging from their fortified caves at night to steal food from the American garrison. The last two holdouts, Naval machine gunners Yamakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki, surrendered on January 6, 1949.

7.1. Allied Perspectives

American military leaders and soldiers who fought against Kuribayashi expressed considerable admiration for his skill and tenacity. Lieutenant General Holland Smith, commander of the US forces at Iwo Jima, famously stated, "Of all our adversaries in the Pacific, Kuribayashi was the most redoubtable." He also remarked that Kuribayashi's "ground deployment was far superior to any I saw in World War I France" and "surpassed the German deployments in World War II." Smith noted that Kuribayashi's character was deeply reflected in the island's underground defenses, which allowed for sustained resistance unlike previous island battles where organized resistance collapsed quickly.

The official US Marine Corps history described Kuribayashi as "one of the most formidable enemies Americans faced in the war." It praised his "innovative thinking and iron will," noting that he "learned much from his US service" and "maximized the terrain" of Iwo Jima. The report highlighted his realistic approach, his decision to avoid "water's edge defense" and "banzai charges," and his implementation of an "attrition, psychological, long-term resistance" strategy. Despite being deprived of naval and air support, Kuribayashi "proved to be a resolute and capable field commander." Admiral Chester Nimitz also acknowledged Kuribayashi's efforts, stating that he "undertook to make Iwo Jima the most impregnable 8 square miles of island fortress in the Pacific." Historian Samuel Morison observed that Kuribayashi's "defense combined benefits of old water's edge and new deep defense." The respect for Kuribayashi extended to the rank-and-file, with one US Marine reportedly saying, "I hope there's no one else like Kuribayashi among the Japs." British historian Antony Beevor also praised Kuribayashi as an "excellent cultured man, nuanced cavalry officer" who "prepared thoroughly" for the battle despite having no illusions about its outcome.

7.2. Japanese Re-evaluation

After the war, General Kuribayashi's name gained a place of honor in post-war Japanese history, often mentioned alongside other outstanding commanders like Isoroku Yamamoto. However, his general public recognition in Japan was limited for many years, as he was a commander who died in a localized battle and had few prominent military episodes outside of Iwo Jima.

This changed significantly with the publication of Kumiko Kakehashi's 2005 book, Chiru zo Kanashiki Iwo Jima Soshikikan Kuribayashi Tadamichi (So Sad to Fall in Battle: Iwo Jima Commander-in-Chief Tadamichi Kuribayashi), and the subsequent release of Clint Eastwood's 2006 Hollywood film, Letters from Iwo Jima. These works brought his story to a wider international audience, and as historian Iku Hata noted, Kuribayashi's name "established status as 'the greatest general of the Pacific War'."

Kuribayashi's wife, Yoshii Kuribayashi, who was only 40 years old when her husband died, worked tirelessly to raise their children without a father. Their daughter, Takako Kuribayashi, recalled, "My mother had been brought up as a lady, and even after getting married she had been taken care of by my father. She had never worked in her life before, but she still managed to raise us during the terrible years after the war by doing things like selling cuttlefish out on the street. And more than that, she sent not just my elder brother, but me, a girl, to university." Yoshii Kuribayashi later represented Japanese families of war dead at reunions with American veterans on Iwo Jima, including the 1970, 1985, and 1995 Reunions of Honor, where she expressed gratitude for their friendship.

Recent discoveries of his childhood diary and report cards from his birthplace have revealed previously unknown details about his early life, including a period when he was temporarily adopted into the Kurata family. His grave is located at Meitoku-ji in Matsushiro, Nagano, though it contains no remains. The family altar at his ancestral home in Matsushiro holds a stone from Iwo Jima and a letter from a surviving non-commissioned officer who participated in the final assault, sent to Yoshii in 1946, detailing the events of that night. In 1967, Kuribayashi was posthumously awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun.

8. Personal Life and Literary Pursuits

Beyond his military command, Tadamichi Kuribayashi was a devoted family man with a notable talent for writing and poetry.

8.1. Family Correspondence

Kuribayashi was known for his diligent correspondence with his family, especially during his overseas assignments and his final posting to Iwo Jima. His letters from his time in North America often included his own illustrations, creating "picture letters" for his young son, Taro, who was still learning to read. These letters, filled with humor and observations from his travels in cities like Boston and Buffalo, revealed his personal sentiments and familial bonds.

From Iwo Jima, his letters to his family, particularly to his daughter Takako (whom he affectionately called "Tako-chan"), showcased a deeply paternal side, often devoid of military formality. He meticulously wrote about his concerns for his home and family's well-being, providing detailed advice on daily life. For instance, he expressed regret for not fixing a draft in their kitchen and included a diagram for Taro to complete the repair. These letters, which include mundane details about the lack of spring water, the prevalence of insects, and the absence of modern amenities on Iwo Jima, offer a poignant glimpse into his personal struggles amidst the "living hell" of the island. Many of these letters have since been compiled and published, including Gyokusai Soshireikan no Etegami (Picture Letters from the Commander-in-Chief, 2002) and Kuribayashi Tadamichi Iwo Jima Kara no Tegami (Tadamichi Kuribayashi: Letters from Iwo Jima, 2006). His family, having evacuated to Nagano Prefecture, survived the Tokyo air raids that destroyed their home.

8.2. Literary and Poetic Contributions

Kuribayashi possessed significant literary talent, stemming from his early interest in journalism. He was known as a cultured military officer and contributed to the lyrics of several martial songs during his service in the Army Ministry's Military Affairs Bureau, notably assisting in the selection of Aiba Shingunka in 1938. His poetic skill is most famously demonstrated in the three waka poems he sent to Imperial Headquarters as part of his farewell message from Iwo Jima, which subtly conveyed his sorrow and protest against the sacrifices demanded by the military command.

9. In Popular Culture

Tadamichi Kuribayashi's portrayal in popular culture, particularly in film, has significantly shaped public perception of him. He is best known to an international audience for his depiction in Clint Eastwood's 2006 film Letters from Iwo Jima. In the film, Kuribayashi was portrayed by Japanese actor Ken Watanabe. Screenwriter Iris Yamashita praised Watanabe's performance and Eastwood's direction, stating that "the many nuances of Tadamichi Kuribayashi came to life onscreen... expressing the perfect sense of the balance of the gentleness and warmth of the family man, combined with the strength, practicality and regality of the commanding officer." The film's original working title, Lamps Before the Wind, was inspired by a line Kuribayashi wrote to his son Taro: "Your father's life is like a lamp before the wind."

Kuribayashi was also portrayed by Iemasa Kayumi in episode 23, "Iwo Jima Operation," of the 1972 Japanese animated documentary series Animentary Ketsudan.

10. Ranks and Awards

Tadamichi Kuribayashi received numerous promotions and honors throughout his distinguished military career.

10.1. Promotion History

| Rank | Date |

|---|---|

| Second Lieutenant (少尉Sho-iJapanese) | December 1911 |

| First Lieutenant (中尉Chu-iJapanese) | July 1918 |

| Captain (大尉Tai-iJapanese) | August 1923 |

| Major (少佐Sho-saJapanese) | March 1930 |

| Lieutenant Colonel (中佐Chu-saJapanese) | August 1933 |

| Colonel (大佐Tai-saJapanese) | August 1937 |

| Major General (少将Sho-shoJapanese) | March 1940 |

| Lieutenant General (中将Chu-joJapanese) | June 1943 |

| General (大将Tai-shoJapanese) | March 17, 1945 (posthumous) |

10.2. Awards

Kuribayashi received several significant awards during his service and posthumously:

- Order of the Rising Sun with Gold and Silver Star (2nd class)

- Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon (3rd class)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (posthumous, December 23, 1967)

- Order of the Rising Sun (4th class, April 29, 1934)

- Showa 6-9 Incident Commemorative Medal (April 29, 1934)

- 2600th Imperial Anniversary Commemorative Medal (November 10, 1940)

He was not awarded the Order of the Golden Kite.