1. Overview

Shigenori Tōgō (東郷 茂徳Tōgō ShigenoriJapanese, 10 December 1882 - 23 July 1950) was a prominent Japanese diplomat and politician who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Empire of Japan at both the outset and conclusion of the Pacific War during World War II. He also held ministerial positions such as Minister of Colonial Affairs in 1941 and Minister for Greater East Asia in 1945. Tōgō's career was marked by his consistent, albeit often unsuccessful, advocacy for diplomatic solutions to avert war, particularly with the United States and other Western powers. Despite signing the declaration of war, he worked tirelessly towards an early peace and ultimately played a crucial role in negotiating Japan's surrender. His life was further shaped by his unique background, being a descendant of Koreans who settled in Kyushu, which brought both personal and professional challenges. Following the war, Tōgō was arrested and convicted as an A-class war criminal by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, serving a prison sentence until his death.

2. Early Life and Background

Shigenori Tōgō's early life was deeply influenced by his unique ancestral background and the societal context of his upbringing in Japan.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Tōgō was born on 10 December 1882, in Hioki District, Kagoshima, specifically in Naeshirogawa village (now part of Higashiichiki-cho Miyama, Hioki, Kagoshima). His family was descended from Korean potters who were brought to Japan by Shimazu Yoshihiro after Toyotomi Hideyoshi's campaigns against Korea in the late 16th century. These Korean descendants were settled in Naeshirogawa by the Satsuma Domain, where they were instructed to maintain their Korean customs, forbidden from using Japanese names, and restricted from marrying outside their community, while also being protected from abuse by outsiders. Many of these villagers were given a status lower than that of local samurai, but still received preferential treatment.

With the Meiji Restoration, the traditional status system changed, and Tōgō's family was designated as "commoners," leading to increased discrimination. In 1880, Tōgō's grandfather, Park Igoma, along with 363 other men from Naeshirogawa, petitioned the Kagoshima Prefectural Office to be re-registered as "samurai," but their requests were repeatedly denied until the last petition in 1885. The following year, in 1886, Tōgō's father, Park Suseung (박수승Park SuseungKorean, 1855-1936), purchased the family register of a low-ranking samurai family named "Tōgō," officially changing their surname from "Park" to "Tōgō" and integrating them into the samurai class. This was done when Shigenori was just four years old. Despite the name change, the Tōgō surname was common in Kagoshima and held no relation to Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō. Although his father was not a potter, he built wealth by selling pottery made by employed potters to foreign buyers in Yokohama.

Tōgō attended Shimo-Ijuin Elementary School, where he was known as an avid reader. He received private tutoring in classical texts, including Confucius's Analects. His niece, Yamaguchi Toshi, later recalled that he was a "study worm" who would sit at his desk until his clothes wore out, constantly flipping through books. He was a quiet child who spoke only when necessary and rarely made jokes. Due to his Korean heritage, Tōgō often faced ostracism from his Japanese classmates, and his only close friend was Sakimoto Yoshio, the son of a farmer, who shared a similar sense of alienation. Sakimoto later recounted that they would often study in quiet places like the Terukuni Shrine grounds to avoid harassment from other children. Tōgō reportedly carried a pocket English dictionary everywhere, memorizing pages and even tearing and swallowing them once mastered.

In 1896, he entered Kagoshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kagoshima Prefectural Tsurumaru High School). In September 1901, he advanced to the newly established Seventh Higher School Zoshikan (now Kagoshima University), where he pursued an interest in German literature, influenced by his teacher, Masao Katayama. Despite his father's desire for him to study law and pursue a career in the Ministry of Home Affairs as a prefectural governor, Tōgō chose literature. In September 1904, he enrolled in the German Literature Department of Tokyo Imperial University. There, Katayama introduced him to the German literary scholar Shinichiro Tobari, and the three formed a literary group called "Sankai." During his time at Tokyo Imperial University, Tōgō's academic performance was poor due to illness and a mismatch with his professors' teaching style, often resulting in him secluding himself in the library. He graduated a year later than his peers, ranking last in his class. He also suffered a fire at his lodging, losing all his books. These setbacks led him to abandon his dream of becoming a German literary scholar or literary critic.

2.2. Entry into Diplomatic Service

After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University in July 1908, Tōgō briefly worked as a German language instructor at Meiji University. Despite his earlier academic struggles, he aspired to a diplomatic career. He took the High Civil Service Examination for diplomats and consuls multiple times, finally passing on his third attempt in 1912. His father, Park Suseung, was immensely proud of his son's achievement, seeing it as a significant step that changed their family's social standing. He celebrated Tōgō's success by hosting a week-long feast for the villagers. Following this, Park Suseung moved their registered domicile to Kagoshima City, formally severing ties with Naeshirogawa village and its association with their Korean ancestry that had been maintained for nearly 300 years. Tōgō entered the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in 1912. His early colleagues noted his strong command of classical Chinese and other languages, his sharp analytical skills, and his reserved demeanor, which senior officials found easy to work with.

3. Diplomatic Career

Tōgō's diplomatic career spanned several critical decades, marked by postings in key international capitals and his involvement in sensitive negotiations.

3.1. Overseas Postings and Assignments

Tōgō's first overseas assignment was to the Japanese consulate in Mukden, Manchuria, in 1913, serving as a consular attaché. In 1916, he was transferred to the newly established Japanese legation in Bern, Switzerland. From 1919 to 1921, Tōgō was part of a Japanese diplomatic mission to Weimar Germany in Berlin, following the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the two nations after Japan's ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. During this period, Germany was experiencing political turmoil, including the Kapp Putsch, but Japanese-German relations remained relatively stable.

Upon his return to Japan in 1921, he was assigned as a secretary to the Bureau of North American Affairs. In 1923, he became the head of the First Section of the European and American Bureau, primarily handling negotiations with the Soviet Union. In 1926, he was appointed as the chief secretary to the Japanese embassy in the United States, moving to Washington D.C.. He returned to Japan in 1929 and, after a brief stay in Manchuria, was dispatched to Germany as a counselor at the German Embassy. In 1932, Tōgō served as the Secretary-General of the Japanese delegation to the largely unsuccessful World Disarmament Conference in Geneva.

In 1933, Tōgō returned to Japan to assume the directorship of the Bureau of North American Affairs but suffered a severe automobile accident that left him hospitalized for over a month. He later became the Director of the European and African Bureau of the Foreign Ministry (1934-1937). In 1935, the North Manchurian Railway was transferred from the Soviet Union to Japan.

3.2. Key Diplomatic Negotiations and Achievements

In 1937, Tōgō was appointed as the Japanese Ambassador to Germany, serving in Berlin until 1938. By this time, Nazism had risen to power, and the political landscape had dramatically shifted. Germany was aggressively expanding, invading Austria and Czechoslovakia, and Jewish persecution was evident, with synagogues in Berlin being burned. Tōgō, a connoisseur of German literature and culture, developed a strong aversion to the Nazi regime. He clashed with Hiroshi Ōshima, the military attaché in Berlin who favored an alliance with Nazi Germany, and with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Nazi Foreign Minister. Tōgō's opposition to the Nazi alliance ultimately led to his dismissal as Ambassador to Germany.

Following his diplomatic stint in Germany, Tōgō was reassigned to Moscow as the Ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1938 to 1940. At this time, Japanese-Soviet relations were strained due to the 1936 Anti-Comintern Pact. Despite this, Tōgō developed a mutually respectful relationship with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov through negotiations on the Soviet-Japanese Fishery Agreement and the ceasefire following the Battles of Khalkhin Gol between Japan and the Soviet Union. He was highly regarded by Molotov as a diplomat who vigorously asserted Japan's national interests.

This improved relationship facilitated negotiations for a Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact. Tōgō's aim was to improve relations with the United States and resolve the protracted Second Sino-Japanese War (known in Japan as the China Incident). The proposed terms included the Soviet Union ceasing aid to Chiang Kai-shek's regime in exchange for Japan abandoning its concessions in Northern Sakhalin. However, when the Second Fumimaro Konoe Cabinet was formed and Yōsuke Matsuoka became Foreign Minister, Matsuoka, influenced by the Army's opposition to abandoning the Sakhalin concessions, ordered Tōgō's recall to Japan. Matsuoka subtly encouraged Tōgō to retire from the Foreign Ministry, but Tōgō refused, instead challenging him to initiate formal disciplinary action. The Neutrality Pact eventually signed by Matsuoka, while seemingly a diplomatic achievement, did not lead to the intended improvement in US-Japan relations, largely due to the existing Tripartite Pact, increased US economic sanctions following Japan's advance into French Indochina, and the worsening relationship between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Moreover, the final pact did not include the abandonment of Northern Sakhalin concessions by Japan, nor the cessation of Soviet aid to the Kuomintang, leaving Tōgō dissatisfied. It primarily served to allow the Soviet Union to focus on Nazi Germany's potential invasion and indirectly supported Japan's southward expansion on the continent. Saionji Kinmochi, a former Foreign Minister and Elder Statesman, was reportedly deeply disheartened upon hearing rumors of Tōgō's impending forced resignation from the Foreign Ministry due to Matsuoka's actions.

4. Political Career and Government Service

Tōgō's transition into political roles placed him at the heart of the Japanese government during its most tumultuous period, where he often found himself at odds with the prevailing militaristic sentiments.

4.1. Minister of Foreign Affairs during World War II

In October 1941, Tōgō was appointed as Foreign Minister in the Hideki Tōjō Cabinet. It is believed that Prime Minister Tōjō, despite his hawkish stance towards the United States, changed his attitude after a direct instruction from Emperor Shōwa to prioritize avoiding war with the US. Tōjō subsequently appointed Tōgō, a known proponent of diplomacy with the US. Tōgō, although a seasoned professional diplomat, was not part of the Foreign Ministry's mainstream and had limited internal connections due to his reserved nature. Upon taking office, he restructured the American Bureau, appointing Haruhiko Nishi as Vice-Minister, Kumakazu Yamamoto as Director of the American Bureau (concurrently Director of the East Asian Bureau), and Toshikazu Kase as Chief of the American Section. To reassert control within the ministry, he also requested the resignation of one pro-Axis ambassador and put two section chiefs and one administrative official on leave.

Tōgō, following the Emperor's and Tōjō's directives, immediately initiated negotiations to avoid war with the United States. He proposed a compromise plan, known as "Plan A," which stipulated the withdrawal of Japanese troops from North China, Manchuria, and Hainan Island within five years, and from other regions within two years. However, this proposal faced strong opposition from the Imperial Japanese Army and met with a rigid stance from the American side, making a settlement unlikely.

Consequently, "Plan B," drafted by Kijūrō Shidehara and revised by Shigeru Yoshida and Tōgō, was submitted. This plan aimed to revert the situation to before the freezing of Japanese assets in the US, on the conditions of Japan's withdrawal from Southern French Indochina and an American commitment to supply oil to Japan. The military leadership added a condition that the US government should work towards peace between Japan and China and refrain from interfering in Chinese affairs. This revised plan was presented to US Secretary of State Cordell Hull via Special Envoy Saburō Kurusu and Ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura.

Upon reading the Hull Note, Tōgō reportedly felt "eyes dimmed with despair." He believed that the terms of the Hull Note left Japan with no choice but to commit national suicide or go to war. He presented the Hull Note to the Emperor as an "ultimatum," leading to the decision to commence the Pacific War during an Imperial Conference. Although the Hull Note itself did not contain any ultimatum and explicitly stated it was a tentative proposal, Tōgō later argued during the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) that the conditions presented by the Hull Note were unacceptable, forcing Japan into war.

Despite Yoshida Shigeru urging him to resign, Tōgō refused, stating that as the head of diplomacy responsible for the negotiations, he felt it was his duty to sign the declaration of war himself rather than foisting the responsibility onto others. He also believed that his resignation would only lead to the appointment of a pro-military foreign minister, making an early peace even more difficult.

At the Imperial Conference on 1 December 1941, Emperor Hirohito reportedly cautioned Prime Minister Tōjō to ensure that the attack did not commence before the diplomatic notification was delivered. Ambassador Nomura also cabled Tokyo on 27 November, advising against an unannounced attack, citing concerns about international trust and potential negative propaganda. Tōgō then negotiated with high-ranking Navy officials, including Admiral Osami Nagano and Vice-Chief of Staff Seiichi Itō, who initially preferred a surprise attack. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto of the Combined Fleet also traveled to Tokyo to express strong opposition to an unannounced attack. An agreement was reached to deliver the notification at 1:00 PM Washington time (3:00 AM Japan time) on 7 December, with the attack commencing at 1:20 PM. However, due to administrative delays at the Japanese embassy in Washington D.C., the notification was delivered at 2:20 PM, 1 hour and 20 minutes after the attack on Pearl Harbor had begun. Crucially, the "Memorandum of the Imperial Government's Notification to the United States" delivered at this time was not a declaration of war or a final ultimatum. Tōgō later argued at the IMTFE that he considered this notification equivalent to a declaration of war, asserting that Japan had intended to issue a declaration before the attack, and the delay was an error. This became the basis for the Japanese defense argument that the delay was an accident.

The delay in delivering the diplomatic note before the attack led the Allies to accuse Japan of a "treacherous sneak attack," which became one of the key charges against Tōgō at the IMTFE. Tōgō initially testified to the IMTFE that the Navy had pushed for an unannounced attack. However, under cross-examination by John Brannan, Nagano Osami's defense lawyer, Tōgō revealed that Shimada and Nagano had threatened him, telling him it would be "unwise" to disclose the Navy's actions. Shimada acknowledged making the statement but claimed it was out of concern for Tōgō.

Tōgō remained Foreign Minister after the war's outbreak, seeking opportunities for an early peace. However, he resigned on 1 September 1942, due to strong opposition to Prime Minister Tōjō's plan to establish a separate Ministry of Greater East Asia for occupied territories, which Tōgō viewed as an unnecessary duplication of the Foreign Ministry's functions and a move that would lead other nations to believe Japan was treating other Asian countries as colonies. He also saw it as an attempt to undermine the Tōjō Cabinet, which he felt was lukewarm about achieving an early peace. Though appointed to the Upper House of the Diet of Japan, he largely remained in retirement for most of the war.

4.2. Other Ministerial Roles

Beyond his primary role as Foreign Minister, Tōgō served in other ministerial capacities reflecting the wartime expansion of Japan's sphere of influence. In October 1941, during his first tenure as Foreign Minister, he concurrently held the position of Minister of Colonial Affairs until December 1941. Later, upon the formation of the Kantarō Suzuki cabinet in April 1945, Tōgō was asked to return to his former position as Minister of Foreign Affairs and was concurrently appointed as Minister for Greater East Asia until August 1945. These roles placed him at the intersection of Japan's wartime administrative and foreign policies.

5. Peace Negotiations and End of War

Tōgō's final period in government was consumed by desperate efforts to bring about an end to World War II, a mission he believed was crucial to Japan's survival.

5.1. Efforts to Avoid War

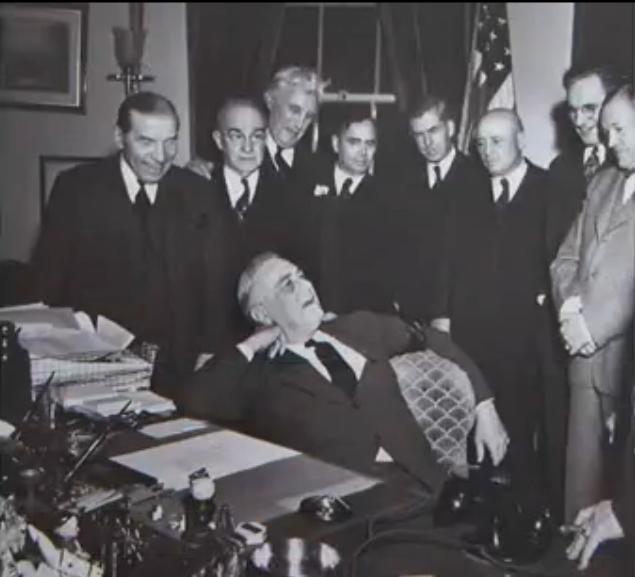

Tōgō consistently opposed war with the United States and other Western powers, believing it was unwinnable for Japan. Alongside Mamoru Shigemitsu, he made unsuccessful, last-ditch attempts to arrange direct, face-to-face negotiations between Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe and US President Franklin Roosevelt in a desperate bid to prevent armed conflict. Despite these efforts, the war escalated, and Tōgō, once the decision to attack was made, signed the declaration of war, stating he disliked placing the responsibility for diplomatic failure on others. He also worked quickly to conclude an alliance between the Japanese Empire and Thailand on 23 December 1941. In an attempt to pursue a more reconciliatory policy towards Western powers, Tōgō announced on 21 January 1942, that the Japanese government would uphold the Geneva Conventions, even though it had not signed them.

5.2. Negotiations for Surrender

By 9 July 1944, with the fall of Saipan, Tōgō recognized that Japan's defeat was inevitable. He began studying histories of national defeat to understand how to preserve Japan's fundamental identity, particularly the Imperial system. In his memoirs, Jidai no Ichimen (The Cause of Japan), he wrote, "Japan's Imperial system must be defended under all circumstances. While punishment for defeat is unavoidable, the degree of that punishment is the issue. It is necessary that fatal conditions are not imposed, and therefore, an end to the war is needed before national power is completely exhausted."

When Admiral Kantarō Suzuki formed his cabinet in April 1945, Tōgō was asked to return as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Despite his initial reluctance, he accepted the post after Suzuki promised him full authority over diplomatic matters, recognizing Tōgō as the only one capable of handling the complex task of ending the war. At this time, Germany's defeat in Europe was imminent, and Japan faced the prospect of increased Allied military pressure in the Pacific and potential Soviet entry into the war, yet the military still advocated for a decisive final battle on Japanese soil.

Tōgō, acting on the Emperor's wishes, sought avenues for peace. He proposed forming a "Big Six" meeting comprising the Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Army and Navy Ministers, and the Chiefs of Staff of the Army and Navy. He sought a forum where these top leaders could discuss sensitive matters candidly without pressure from lower-ranking military staff. This proposal was accepted, with the condition that discussions remain confidential.

After Germany's surrender in May 1945, calls for an unconditional peace settlement through Soviet mediation grew in Japan. During the first "Big Six" meeting in mid-May, Army Chief of Staff Yoshijirō Umezu pointed out the increasing Soviet military presence in the Far East, raising the need for negotiations with the Soviet Union to prevent their entry into the war. Tōgō proposed exploring peace negotiations through Soviet mediation. However, Army Minister Korechika Anami opposed this, arguing that Japan was not defeated and that the primary goal should be to prevent Soviet intervention rather than seek peace. Naval Minister Mitsumasa Yonai mediated, and the consensus was to first aim for Soviet non-intervention and benevolent neutrality, with peace negotiations to follow depending on Soviet responses. The group also agreed to consider concessions such as the return of Sakhalin, transfer of fishing rights, and neutralization of southern Manchuria to prevent Soviet entry.

Following this decision, Tōgō dispatched former Prime Minister Kōki Hirota, an expert on Soviet affairs, to meet with Soviet Ambassador Yakov Malik in Hakone. However, two meetings yielded no concrete results, as both sides cautiously explored the other's intentions without revealing their own. Malik, unaware of the Soviet Union's intention to join the war against Japan, reported to Molotov that he would not make any statements unless specific demands were received. Molotov, with Joseph Stalin's approval, supported this stance, instructing Malik to only meet Hirota upon request and to report general inquiries via diplomatic pouch only, effectively prolonging the talks to serve Soviet interests. Satō Naotake, the Japanese Ambassador in Moscow, advised against relying on Soviet mediation, but Tōgō disregarded his warnings.

This decision to focus on Soviet mediation led to the cessation of all other secret peace negotiations that had been conducted through various channels in Sweden, Switzerland, and the Vatican. Despite Tōgō's prior experience with Soviet diplomatic cunning, he pursued this path. He later justified this by stating that he wanted to guide the situation toward a negotiated peace since direct talks with the US and Britain would likely demand unconditional surrender. He also cited Emperor Hirohito's favorable view of Soviet mediation as an influencing factor.

As time passed with no clear indication from the Soviets, Emperor Hirohito, on 22 June, personally decided to seek peace negotiations through the Soviet Union, beyond mere prevention of their entry. The cabinet resolved to dispatch former Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe as a special envoy to Moscow and sounded out the Soviets in July. However, the Soviets repeatedly delayed their response, citing preparations for the upcoming Potsdam Conference. This stalemate led Japan directly to face the Potsdam Declaration on 26 July.

5.3. Response to the Potsdam Declaration

Upon learning of the Potsdam Declaration, Tōgō concluded that Japan should accept it, but only after clarifying ambiguous points and understanding the Soviet Union's stance, given their non-participation in the declaration. He discussed this with Emperor Hirohito, who, according to Tōgō's notes, felt the declaration could serve as a basis for negotiation, even if not immediately acceptable. Other accounts suggest the Emperor showed no particular interest in the declaration. Emperor Hirohito ultimately agreed with Tōgō's strategy of waiting for Moscow's response.

However, Army Minister Anami strongly opposed Tōgō's view, advocating for a complete rejection of the Potsdam Declaration. Prime Minister Suzuki and Naval Minister Yonai, who were generally inclined towards peace, underestimated the declaration's significance, believing that Soviet negotiations would still secure peace. Consequently, the government decided neither to accept nor reject the declaration, opting for a "wait-and-see" approach. The declaration's content, however, had already been broadcast internationally via shortwave radio. Although the government initially decided to release a censored version as minor news without comment, newspapers on 28 July interpreted the government's stance with headlines like "laughable" (Yomiuri Shimbun) and "ignoring" (Asahi Shimbun), the latter being "Mokusatsu" (黙殺Japanese). This "Mokusatsu" was interpreted by the Allies as a rejection of the declaration, leading to the continuation of bombing campaigns. Tōgō protested Suzuki's public statement, considering it a violation of cabinet decisions.

This diplomatic misstep was soon followed by devastating events: the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on 6 August, and the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria on 8 August.

5.3.1. End of War

The rapid deterioration of the situation prompted a Supreme War Guidance Council meeting on 9 August. Tōgō vehemently argued for accepting the Potsdam Declaration, with the "security of the Imperial House" as the sole condition. Naval Minister Yonai and Privy Council President Kiichirō Hiranuma supported him. However, Army Minister Anami proposed four conditions: maintaining the Imperial House, conducting disarmament by Japan, minimizing occupation, and allowing Japan to punish war criminals. Umezu and Soemu Toyoda, Chief of Naval General Staff, supported Anami, leading to a heated deadlock. Yonai countered Anami's assertion that the war was "fifty-fifty," pointing out complete defeats in Bougainville, Saipan, Philippines, Leyte, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Tōgō argued that even if the first wave of an invasion was repelled, Japan's forces would be exhausted, with no guarantee of victory against subsequent waves.

During this intense debate, the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Late that night, an Imperial Conference was held. Prime Minister Suzuki, unable to resolve the impasse, asked Emperor Hirohito for a "sacred decision." The Emperor, shedding tears, agreed with Tōgō's proposal to accept the Potsdam Declaration, citing the military's unpreparedness for a homeland defense and the risk of Japan's complete annihilation if the war continued. Tōgō's proposed condition for surrender, initially "under the understanding that it does not include a demand to alter the Emperor's legal status," was amended to "under the understanding that it does not include a demand to alter the Emperor's prerogative to rule the state," following Hiranuma's objection, before the Emperor's final decision.

Tōgō instructed Minister Shunichi Kase in Switzerland to protest the atomic bombings, urging a "massive press campaign to expose and attack America's inhumane barbarism...throwing 300,000 innocent civilians into hell is several times more brutal than the Nazis." He also directly protested to Soviet Ambassador Malik regarding the Soviet Union's violation of the Neutrality Pact.

While Allied leaders recognized the necessity of the Emperor and Imperial House to stabilize post-war Japan, Tōgō's condition caused ripples. US President Harry S. Truman questioned whether the Imperial system could be maintained while eradicating Japanese militarism. Though some, like Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal and Secretary of War Henry Stimson, advocated accepting Japan's offer, Secretary of State James F. Byrnes argued against compromise. Forrestal proposed a compromise in which the Allies would define the surrender terms while accepting Japan's conditional acceptance, leading to the "Byrnes Note" presented to Japan on 12 August. This note stated that the Emperor would be "subject to the authority of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers" and that "the ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people." This cleverly allowed for the maintenance of the Imperial system while asserting Allied authority.

Anami and Umezu fiercely demanded a re-inquiry regarding the ambiguity of the Imperial House's status. Tōgō and Yonai argued that a re-inquiry would lead to a breakdown in negotiations. The situation became chaotic, with even Hiranuma siding with the military. Overwhelmed by despair and exhaustion, Tōgō briefly offered his resignation late on 12 August. Suzuki persuaded him to stay, promising another Imperial Conference to resolve the crisis. On 14 August, Emperor Hirohito once again, with tears, expressed his support for Tōgō's proposal, breaking the deadlock and finally leading to Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration.

After signing the surrender documents, Anami visited Tōgō, thanking him cordially despite their heated debates, to which Tōgō replied, "I'm truly glad it ended peacefully." Tōgō meticulously stressed to the Allied forces that the Japanese Army's disarmament should be conducted with the utmost honor. Anami, expressing gratitude for this, departed and committed suicide early on 15 August. Tōgō, who rarely showed emotion, reportedly wept upon hearing the news, saying, "So, he committed harakiri. Anami was truly a good man."

6. Post-War and War Crimes Trial

Following Japan's surrender, Tōgō faced the consequences of his wartime service, enduring a trial that profoundly shaped his legacy.

6.1. Arrest and Imprisonment

After the end of World War II, Tōgō initially retired to his summer home in Karuizawa, Nagano. However, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) soon ordered his arrest on war crimes charges, along with other former members of the Imperial Japanese government. He was subsequently held at Sugamo Prison in Sumida, Tokyo. His initial arrest warrant was delayed due to illness, but he reported for questioning in late September 1945.

6.2. Trial and Conviction

On 17 April 1946, Tōgō was designated an A-class war criminal, formally indicted on 29 April, and transferred to Sugamo Prison on 1 May. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) commenced on 3 May. Tōgō was accused of participating in a joint conspiracy for aggressive war, aiding in the initiation of war through deceitful diplomacy, and continuing to assist in the war's prosecution even after its outbreak, encompassing general war crimes and negligence in their prevention.

For his defense, Tōgō was represented by Haruhiko Nishi (his former Vice-Minister and later Ambassador to the UK), and George Yamaoka, the only Japanese-American lawyer on the American defense team. His son-in-law, Fumihiko Tōgō, handled administrative matters.

Tōgō's individual testimony at the trial began on 15 December 1947. He faced intense cross-examination from the prosecution and occasionally from other defense lawyers, notably John Brannan, counsel for Osami Nagano. Tōgō claimed that Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō, Navy Minister Shigetarō Shimada, and Planning Board President Teiichi Suzuki were the main proponents of the war. He stated that the Imperial Japanese Navy had advocated for an unannounced attack but that he had fought fiercely to limit their demands to the utmost boundaries of international law. He asserted that he did not evade his responsibilities but would not allow others to push their responsibilities onto him. When Brannan pressed him, implying that other witnesses claimed no knowledge of the Navy's push for a surprise attack, Tōgō retorted, "I do not trust the memories of these people. They forgot about the extremely important Imperial Conference of 5 November (which decided on war if negotiations failed in early December) until I mentioned it." He then revealed that Shimada and Nagano had "threatened" him after the trial began, telling him not to mention that the Navy had wanted a surprise attack. This revelation caused a stir, with media outlets dubbing it the "Squid Ink controversy." Shimada, in his later testimony, admitted to the conversation but insisted it was out of concern for Tōgō.

Tōgō also testified that Kōichi Kido did not convey the Emperor's desire for peace to him and that Umetsu Yoshijirō continued to refuse peace, advocating for a decisive battle on mainland Japan. He had heated exchanges with Umetsu and even with Kido's defense lawyer, William Logan, who at one point interjected, "You don't like Kido, do you?"

His intense focus on justifying his own position during the trial drew criticism from some, including Mamoru Shigemitsu, who penned a poem criticizing those who sought to escape responsibility. On 4 November 1948, the Tribunal found Tōgō guilty, concluding that he had participated in a joint conspiracy for war since his time as Director of the European and Asian Bureau, assisted in the war's initiation through deceptive diplomatic maneuvers, and contributed to its prosecution after it began. He was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment, a relatively light sentence compared to others.

Tōgō strongly criticized the IMTFE as an act of "revenge and a show trial" by the victorious nations against the defeated, denying the specific charges against him while acknowledging his "sin" was the failure to prevent war. He asserted that if war was a crime, then British annexation of India and American annexation of Hawaii should also be judged. Despite his criticism, he expressed hope that the international community would establish legal frameworks to prevent war and saw Article 9 of the new Japanese Constitution as a first step in that direction. This perspective later led to a conflict between his son-in-law, Fumihiko Tōgō (who advocated for treaty revision for Japan's security), and his friends, Haruhiko Nishi and Ishiguro Tadaatsu (who believed peace would not be achieved through military alliances and stressed Article 9's spirit), during the revision of the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1960.

7. Personal Life

Shigenori Tōgō's personal life, particularly his marriage to a German woman and his family's unique background, reflected the complexities of his identity and career.

7.1. Marriage and Family

In 1922, despite strenuous objections from his family, Tōgō married Carla Victoria Editha Albertina Anna de Lalande (née Giesecke, 1887-1967). She was the widow of the notable German architect Georg de Lalande (1872-1914), who designed numerous administrative buildings in Japan and its empire, including the Japanese General Government Building in Seoul. Their wedding took place at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Editha was born to a Jewish woman, Anna Giesecke, and a German nobleman, but her father left, and her mother committed suicide shortly after her birth. She was adopted by her aunt and uncle, taking her adoptive father's surname, Pitschke. She came to Japan at age 15 with her adoptive father, who worked for the Russo-Chinese Bank. After his sudden death, her adoptive mother ran a guesthouse in Kobe to make ends meet. At 17, she married Georg de Lalande, a Jewish architect 16 years her senior, in 1905. It was during this time that her adoptive mother, out of jealousy, revealed Editha's birth secret. She had five children from her first marriage: Ursula, Ottilie, Yuki, Heidi, and Guido de Lalande. After Georg's death nine years later, she returned to Germany. She met Tōgō in Berlin when he was stationed there as a diplomat from 1919 to 1921. They fell in love, reportedly bonded by their shared interest in Goethe's romantic poems. Tōgō's personal struggles with his Korean heritage made it difficult for him to marry a Japanese woman, leading him to marry Editha in his forties.

Together, Tōgō and Editha had one daughter, Ise Tōgō (1923-1997). In 1943, Ise married Fumihiko Honjo, a Japanese diplomat. Out of respect for his wife's family, Fumihiko adopted the surname Tōgō, becoming Fumihiko Tōgō (1915-1985). He later served as the Japanese Ambassador to the United States from 1976 to 1980. Fumihiko Tōgō also played a significant role in managing diplomatic crises in Korea, including handling the Kim Dae-jung kidnapping incident in 1973 and efforts to mitigate anti-Japanese sentiment following the Mun Se-gwang incident in 1974. Their son, Kazuhiko Tōgō (born 1945), is a Japanese diplomat and scholar of international relations. Shigenori Tōgō's twin grandsons are Shigehiko Tōgō, a former Washington Post reporter, and Kazuhiko Tōgō, a former Dutch Ambassador and Director-General of the Foreign Ministry's European and Asian Affairs Bureau.

Shigenori Tōgō harbored a deep internal struggle with his Korean blood. Despite outwardly concealing his Korean ancestry, he longed for the country he had never visited. During his time as Director of the European and American Bureau, he confided in an ethnic Korean diplomat, a native of Gyeongju, who had passed Japan's foreign service examination, encouraging him to dedicate himself to an independent Korea. His father, Park Suseung, continued the family pottery business, which had originated from Korean potters. Tōgō's mother, Park Tome (1859-), also of Korean descent, managed her husband's pottery business's accounting and records, displaying an exceptional memory for financial transactions. She learned to read and write despite being illiterate at the time of her marriage. Tōgō's paternal grandmother was reportedly disappointed that her first grandchild was a girl, as the family highly valued male heirs to continue the "Park" lineage, but she rejoiced upon Shigenori's birth. While Tōgō was imprisoned, Shim Hyegil, the 14th generation successor of the Korean potter Sim Sugwan, who was studying at Waseda University, visited him nine times, bringing local Kagoshima snacks.

8. Writings, Evaluation, and Legacy

Tōgō's career and the decisions he made during a tumultuous period have been subject to significant historical evaluation, reflected in his own writings and the assessments of scholars.

8.1. Memoirs and Writings

During his imprisonment, Tōgō, who had initially wished to write a history of civilization explaining the causes of war, decided to write his memoirs instead, as his declining health and prison conditions prevented him from pursuing his original ambition. His memoirs, titled Jidai no Ichimen (時代の一面Japanese, A Facet of the Era), were largely completed before his death and posthumously published as The Cause of Japan (改造社, 1952). The English translation was edited by his former defense counsel, Ben Bruce Blakeney. The memoirs offer Tōgō's personal perspective on his diplomatic career and the events leading up to and during World War II.

8.2. Historical and Critical Assessments

Tōgō Shigenori is widely recognized as a pacifist and a proponent of peace. However, his strategy of relying on the Soviet Union as a mediator for peace has been criticized as a "folly" by some historians, including Naotake Satō, who served as Ambassador to the Soviet Union. Satō, in his post-war reflections, lamented the "waste of a valuable month" in negotiations. Critics argue that Tōgō was unaware of the secret agreements made at the Yalta Conference, where the Soviet Union had promised the Allies its entry into the war against Japan. His reliance on Hirota Koki's protracted negotiations with Soviet Ambassador Malik, which yielded no results from 3 June to 14 July, is often cited as a critical misjudgment. The delay in responding to the Potsdam Declaration, waiting for a Soviet reply, was interpreted by the Allies as rejection, leading to the atomic bombings and Soviet entry into the war. However, William Leahy, Chief of Staff to the US President, also criticized Truman for intentionally disregarding the Soviet mediation efforts.

Critics like Tsuyoshi Hasegawa describe the hope placed in Soviet mediation as "opium" for Japanese leaders and suggest that the "greedy hope to extract more favorable conditions for the maintenance of the Imperial system lured them (the peace faction) to the path to Moscow." Conversely, some historians argue that the expectation of a more favorable, non-unconditional surrender through Soviet mediation was a common belief among the "peace faction" within the government, including Suzuki, Yonai, Kido, and Emperor Hirohito himself. Tōgō himself stated in his memoirs that the Soviet mediation had "largely succeeded" in leading to the "conditional peace" of the Potsdam Declaration, based on information he had heard that the US had prepared a conditional peace proposal after learning of Japan's peace overtures through the Soviets. However, the US had already intercepted and deciphered diplomatic cables between Tōgō and Satō, giving them prior knowledge of Japan's intentions.

8.3. Impact and Influence

Tōgō's efforts in diplomacy during the lead-up to and conclusion of World War II, particularly his opposition to the war and his role in the final surrender, continue to be significant subjects of historical debate. His actions and policies had a profound impact on Japanese foreign relations, the conduct of the war, and the subsequent post-war international order. Tōgō was posthumously enshrined in Yasukuni Shrine as a "Shōwa Martyr" on 17 October 1978.

9. Death

Shigenori Tōgō, who suffered from atherosclerosis, died of cholecystitis (acute gallbladder inflammation) in Sugamo Prison in Sumida, Tokyo on 23 July 1950, at the age of 67. He was buried in Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.

10. Honors and Decorations

- 1916: Order of the Sacred Treasure, 6th Class

- 1920: Order of the Rising Sun, Rays with Rosette, 5th Class

- 1926: Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, 4th Class

- 1931: Order of the Sacred Treasure, 3rd Class

- 1934: Order of the Sacred Treasure, 2nd Class

- 1938: Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star

- 1940: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun; Commemorative Medal for the 2600th Anniversary of the Imperial Rule

- 1941: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure

10.1. Foreign Honors

- 1938: Nazi Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle

- 1939: Kingdom of Italy: Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy

- 1942: Kingdom of Thailand: Knight Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant

- 1943: Kingdom of Italy: Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

11. See also

- History of Japan

- Japanese-German relations

- Japan-Russia relations

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- Battles of Khalkhin Gol

- Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact

- Potsdam Declaration

- Surrender of Japan

- International Military Tribunal for the Far East

- A-class war criminal

- Hideki Tōjō

- Kantarō Suzuki

- Mitsumasa Yonai

- Korechika Anami

- Haruhiko Nishi

- George de Lalande

- Georg de Lalande

- Fumihiko Tōgō

- Kazuhiko Tōgō

12. External links

- [https://www.city.hioki.kagoshima.jp/kanko/kankou/kanko-map/osusume/togoshigenorikinenkan.html Former Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo Memorial Museum] (Hioki, Kagoshima Prefecture)

- [https://www.pref.kagoshima.jp/suisuinavi/11192.html Former Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo Memorial Hall] (Kagoshima Prefecture)

- [https://www.ifsa.jp/index.php?togoshigenori Shigenori Togo] - NPO International Student Association

- [http://alsos.wlu.edu/qsearch.aspx?browse=people/Togo,+Shigenori Annotated bibliography for Shigenori Togo from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues]

- "Speech to the Diet 17 November 1941", New York Times 18 November 1941. (From Ibiblio's Chronological Collection of Documents Relating to the U.S. Entry into World War II)

- Excerpts from Togo's [http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/hando/togo.htm The Cause of Japan]