1. Overview

Setsuko, Princess Chichibu, born Setsuko Matsudaira on September 9, 1909, in Walton-on-Thames, England, was a prominent member of the Japanese Imperial Family and the wife of Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu, the second son of Emperor Taishō and Empress Teimei. Her life spanned a period of immense change in Japan, from the pre-war imperial era to the post-war democratic society. Despite her birth into the distinguished Matsudaira and Nabeshima families, she was technically a commoner before her marriage, a detail that underscores the evolving nature of the Imperial Household.

Known for her international upbringing, including education in the United States, Princess Setsuko became a fluent English speaker and a cultural bridge. Throughout her public life, she embraced significant social roles, notably serving as president of the Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis for 55 years, a tenure that profoundly impacted public health awareness in Japan. Her extensive overseas visits, particularly to the United Kingdom and Sweden, fostered international goodwill and showcased her dedication to diplomatic relations. After the death of Prince Chichibu in 1953, she continued to serve as a tireless advocate for various social welfare organizations. Her autobiography, The Silver Drum: A Japanese Imperial Memoir, offers insights into her unique position within the Imperial Family and her personal reflections on a life dedicated to public service. Her legacy is marked by her unwavering commitment to social contributions and her role in subtly influencing the Imperial Household's modernization.

2. Early Life and Background

Setsuko Matsudaira's early life was marked by a privileged upbringing that blended traditional Japanese aristocratic heritage with a significant international exposure, shaping her perspective and preparing her for a unique role within the Imperial Family.

2.1. Birth and Family

Setsuko Matsudaira was born on September 9, 1909, in Walton-on-Thames, England. Her father, Tsuneo Matsudaira, was a distinguished diplomat and politician who served as the Japanese ambassador to the United States (1924) and later to the United Kingdom (1928), eventually becoming the Imperial Household Minister (1936-1945, 1946-1947). Her mother was Lady Nobuko Nabeshima, a member of the prominent Nabeshima clan.

Her family lineage was deeply rooted in Japanese aristocracy. Her paternal grandfather, Matsudaira Katamori, was the last *大名daimyōJapanese* of the Aizu Domain and head of the Aizu-Matsudaira cadet branch of the Tokugawa clan. Her maternal grandfather, Marquis Naohiro Nabeshima, was the former *大名daimyōJapanese* of the Saga Domain. Her mother's elder sister, Itsuko (1882-1976), married Prince Nashimoto Morimasa, an uncle of Empress Kōjun, connecting Setsuko to even broader imperial circles. Despite this prestigious heritage, Setsuko was technically born a commoner, although both sides of her family maintained close kinship with distinguished *華族kazokuJapanese* aristocratic families connected to the Imperial Family.

2.2. Education and Pre-marriage Life

Setsuko's early years included residences in Beijing, Tianjin, and Washington, D.C., where her father served as a diplomat. From 1925 to 1928, while her father was ambassador to the United States, she was educated at the Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C.. This international exposure contributed significantly to her proficiency in English; she was considered a *帰国子女KikokushijoJapanese* (a term for Japanese children educated abroad) and was known for her ability to deliver speeches in English before foreign audiences.

Her childhood education also included studies at Gakushūin Girls' Primary School, where she became classmates and lifelong friends with Masako Shirasu, the second daughter of Count Aiske Kabayama. Shirasu later described Setsuko as tolerant and diligent in her studies. The close relationship between their families played a crucial role when Aiske Kabayama facilitated the marriage between Prince Yasuhito and Setsuko at the informal request of Empress Teimei. Empress Teimei was particularly keen on selecting a suitable bride for her second son, especially after the controversies surrounding Empress Kōjun's marriage. Setsuko's perceived good health, which raised expectations for children (though ultimately none were born to the couple), further solidified Empress Teimei's choice. While contemporary reports often romanticized a prior meeting between Setsuko and Prince Yasuhito, Setsuko herself later denied these narratives in her writings.

3. Life as Princess Chichibu

Princess Setsuko's life as Princess Chichibu was marked by her marriage into the Imperial Family, her active engagement in imperial duties, and her experiences during a tumultuous period in Japanese history.

3.1. Marriage to Prince Chichibu

On September 28, 1928, at the age of 19, Setsuko Matsudaira married Yasuhito, Prince Chichibu, becoming Princess Chichibu. Due to the then-current Imperial House Law, which stipulated that an imperial consort must be of imperial or *華族kazokuJapanese* (peerage) lineage, Setsuko, who was legally a commoner through her father, had to be formally adopted by her uncle, Viscount Morio Matsudaira (a naval rear admiral and her father's brother), to acquire the necessary peerage status before the marriage.

This union carried significant historical weight, particularly for the people of the Aizu Domain. Setsuko's paternal grandfather, Matsudaira Katamori, was the last *大名daimyōJapanese* of Aizu, a domain famously branded as a "rebel" and "imperial enemy" during the Boshin War and the Meiji Restoration. Her entry into the Imperial Family was seen by former Aizu *samurai* as a profound restoration of their honor and a source of immense pride. Interestingly, three of the four imperial consorts of Emperor Taishō's sons (Empress Kōjun, Princess Setsuko, and Princess Kikuko Takamatsu) were granddaughters of prominent *尊皇攘夷Sonnō JōiJapanese* (royalist) or *佐幕SamakuJapanese* (pro-shogunate) figures, a fact they reportedly found amusing amongst themselves.

Upon her marriage, Setsuko's name was officially changed from Setsuko (節子), which shared a character with Empress Teimei's birth name, Sadako (貞子), to Setsuko (勢津子). This new name was chosen by taking one character from Ise Province (伊勢), historically significant to the Imperial Family, and one from Aizu (会津), symbolizing her ancestral roots. Following the wedding, Princess Setsuko attended her first imperial court ceremony on October 17, 1928, for the Kanname-sai harvest ritual. The couple immediately traveled to pay respects at Ise Grand Shrine and Fushimi Momoyama Ryo (Emperor Meiji's tomb) and later attended Emperor Shōwa's coronation ceremony in Kyoto on November 10. Although their only pregnancy ended in a miscarriage, the marriage was by all accounts a loving and happy one.

3.2. Imperial Role and Public Engagements

As Princess Chichibu, Setsuko actively fulfilled her duties as a member of the Imperial Family, engaging in numerous public and diplomatic activities. In 1937, she accompanied Prince Yasuhito on an extensive tour of Western Europe, representing Japan at the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in Westminster Abbey. Following the coronation, they visited Sweden and the Netherlands as guests of King Gustav V and Queen Wilhelmina, respectively. Towards the end of the trip, while Prince Chichibu met with Adolf Hitler in Nuremberg, Princess Setsuko remained in Switzerland.

Princess Setsuko held a deep affection for both the United States and the United Kingdom. As an ardent Anglophile, she was profoundly saddened by Japan's decision to join the Axis powers and enter World War II. Her fluency in English and her international background made her a valuable asset in fostering international relations, particularly with Western nations.

3.3. Imperial Succession and Wartime Experience

When Princess Setsuko married Prince Yasuhito in 1928, Emperor Shōwa and Empress Kōjun had only daughters, with no male heir yet born. This placed Prince Yasuhito first in line to the throne, which created a period of heightened scrutiny and political maneuvering within the Imperial Household. Empress Dowager Teimei, Prince Yasuhito's mother, actively sought to promote Princess Setsuko's role and encourage childbearing. The Empress Dowager sent gifts to Empress Kōjun for a safe delivery and, for the Chichibu couple's first wedding anniversary, sent a silk depiction of a crane playing under a pine tree-symbols of longevity and prosperity, with the crane alluding to Tsuruga Castle (Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle), an ancestral home of Setsuko's family, and the pine referring to Prince Yasuhito's personal emblem (young pine). She also composed *和歌wakaJapanese* poems expressing her hopes for the couple to be blessed with children.

Prince Yasuhito, known as the "Sports Prince" for his athletic interests, enjoyed significant public popularity. Given the lack of a male heir, there was a movement to endorse him as the successor. The succession issue was ultimately resolved with the birth of Akihito (the future Emperor Akihito) in 1933, the fifth child of Emperor Shōwa and Empress Kōjun.

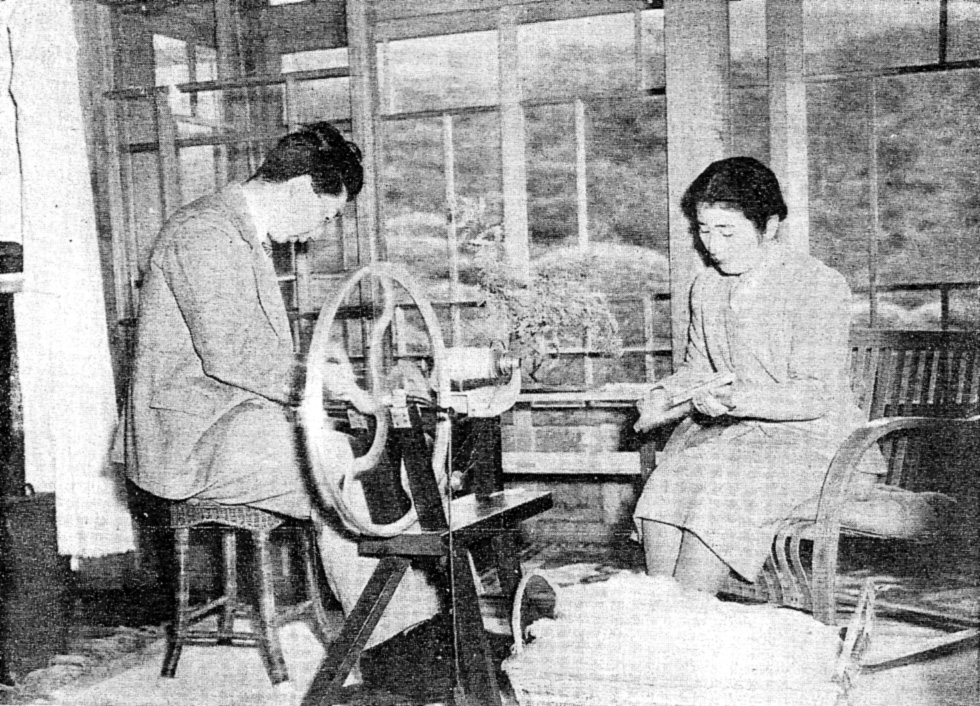

In 1939, at the behest of Empress Kōjun, Princess Setsuko became the president of the Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis. Ironically, the following year, Prince Yasuhito was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Princess Setsuko, having educated herself on the disease due to her new role, recognized early symptoms in her husband, though a definitive diagnosis by doctors was delayed. From 1941, the couple relocated to Gotemba for Prince Yasuhito's recuperation, where they remained through the end of World War II. Despite Princess Setsuko's diligent care and active engagement in public duties on her husband's behalf, Prince Yasuhito succumbed to pulmonary tuberculosis on January 4, 1953, at the age of 50.

4. Widowhood and Later Life

Following the death of Prince Chichibu, Princess Setsuko dedicated her life to extensive public service, leaving a lasting legacy through her unwavering commitment to social welfare and international relations.

4.1. Public Service and Advocacy

After her husband's passing in 1953, Princess Chichibu devoted herself to a life of public service. She continued her role as president of the Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, a position she held for an remarkable 55 years until she passed it to Princess Kiko in 1994. Under her leadership, the society established the Chichibunomiya Memorial Clinic for Tuberculosis Prevention in 1957.

Princess Setsuko also held honorary presidencies for the Britain-Japan Society and the Sweden-Japan Society, reflecting her strong connections and affection for these nations. She served as an honorary vice president of the Japanese Red Cross. Her fluency in English proved invaluable in her numerous semi-official visits abroad, which included multiple trips to the United Kingdom (1962, 1967, 1974, 1979, 1981) and Sweden (1962). She also visited France and Denmark in 1962 and traveled to South Korea in 1970 to attend the funeral of Yi Un, the last Crown Prince of Korea. In 1985, she visited Nepal. Even after suffering a myocardial infarction in 1986, which confined her to a wheelchair, she continued to perform her public duties with determination.

4.2. Death and Legacy

Princess Setsuko died from heart failure in Tokyo on August 25, 1995, just shy of her 86th birthday. She was interred in the same burial plot as Prince Yasuhito at Toshimagaoka Cemetery in Tokyo.

With Princess Setsuko's death, the Chichibu princely house (宮家miyakeJapanese) became extinct, as she and Prince Yasuhito had no children. In accordance with her will, her Gotemba villa was bequeathed to Gotemba City in 1996. The villa was subsequently developed and opened to the public as the Chichibunomiya Memorial Park in 2003, serving as a tranquil public space and a reminder of her life. Additionally, many of the Chichibu princely house's cherished belongings and artifacts were donated to the Museum of the Imperial Collections within the Imperial Palace, ensuring their preservation and public access as part of her enduring legacy.

5. Assessment and Impact

Princess Setsuko's life had a multifaceted impact on both Japanese society and international relations, marked by significant contributions and some notable controversies that reflect the socio-political climate of her era.

5.1. Contributions and Positive Impact

Princess Setsuko is remembered for her significant social contributions and positive influence, particularly in public health and international diplomacy. Her nearly lifelong dedication to the Society for the Prevention of Tuberculosis as its president brought crucial attention and resources to combat the disease, which was a major public health concern in post-war Japan. Her active engagement went beyond ceremonial duties; she established clinics and advocated for improved prevention and treatment methods. This consistent public service positioned her as a compassionate figure dedicated to the well-being of the Japanese people.

Furthermore, her international upbringing and fluency in English made her an exceptional ambassador for Japan. Her numerous visits to the United Kingdom and Sweden, often on semi-official diplomatic missions, played a vital role in enhancing bilateral relations and fostering goodwill. She was particularly admired by the British Royal Family, with King Charles III reportedly referring to her as his "Japanese grandmother." Her ability to bridge cultural divides and her genuine affection for other nations contributed to a more positive image of Japan on the global stage, especially during the post-war period. Her personal qualities, such as her tolerance and diligence, also made her a respected figure within the Imperial Family and among the public.

5.2. Criticisms and Controversies

While generally admired, Princess Setsuko was involved in certain social debates, most notably her strong opposition to the marriage of Crown Prince Akihito (the future Emperor) and Shōda Michiko in 1959. This opposition was shared by Empress Kōjun, Princess Kikuko Takamatsu (wife of Emperor Shōwa's third brother), and Setsuko's own mother, Nobuko Matsudaira. Nobuko, who was also the head of the Tokiwakai, an association of former Imperial and peerage families, reportedly mobilized right-wing groups to pressure the Shōda family into declining the proposal.

The opposition stemmed from several factors. There was a personal disliking of Michiko among some imperial family members, but more significantly, the marriage was viewed as a symbol of the "decline of upper-class society" following the post-war reforms that saw the demotion of collateral imperial branches to commoner status and the abolition of the *華族kazokuJapanese* peerage system. For some, Michiko's commoner background threatened the traditional exclusivity of the Imperial Household. However, despite her personal reservations and those of her allies, Princess Setsuko ultimately voted in favor of the marriage during the Imperial House Council meeting, demonstrating her understanding of the constitutional process and her commitment to the stability of the Imperial Family, even when it conflicted with her private opinions.

6. Personal Life and Anecdotes

Princess Setsuko's personal life offered glimpses into her character, revealing her hobbies, relationships, and unique experiences.

A specific variety of orange-pink rose, presented by J. Harkness of England in 1971, was named 'Princess Chichibu' in her honor. Her husband, Prince Yasuhito, had a fondness for the Japanese Alps and frequently went climbing there before falling ill with tuberculosis. His customary guide was Tsunejiro Uchino, known as "Tsune-san of Kamikochi." Uchino, a seasoned mountain man, would informally refer to Princess Setsuko as おかみさんOkamisanJapanese (meaning "madam" or "wife"), a term that reportedly made others around them nervous. However, Prince Chichibu would reassuringly tell Uchino, "Tsune-san, 'Okamisan' is fine," highlighting the relaxed and affectionate dynamic between the imperial couple and their trusted companions.

Princess Setsuko maintained a strong sense of her identity as an Aizu native throughout her life. When Ryōtarō Shiba's novel *王城の護衛者Ōjō no GoeishaJapanese* (The Imperial Castle Guardsman), which depicted her grandfather Matsudaira Katamori, was serialized in a magazine, she immediately read it. She conveyed her appreciation to Shiba through the head of the Aizu-Matsudaira family, Matsudaira Yasusada, expressing that the novel was the first to "fairly write about her grandfather's position."

For many years, the renowned beautician Aguri Yoshiyuki served as Princess Setsuko's trusted hairdresser. Their professional relationship evolved into a warm personal friendship that continued until the Princess's death.

The couple had no surviving children. Towards the end of 1935, while Prince Yasuhito was stationed with the Imperial Japanese Army's 8th Division in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Princess Setsuko showed signs of pregnancy. However, shortly after the February 26 Incident in February 1936, the harsh winter train journey from Hirosaki to Tokyo, undertaken immediately after the coup attempt, reportedly caused her to miscarry.

A poetry monument with her *和歌wakaJapanese* is located in front of Isogo Station on the Negishi Line in Yokohama, erected in May 1970.

7. Works

Princess Setsuko authored and co-authored several significant literary works, primarily her memoirs, which offered a unique insight into her life within the Imperial Family and her personal experiences during a pivotal period in Japanese history.

Her most notable work is her autobiography, The Silver Drum: A Japanese Imperial Memoir. Originally published in Japanese as 銀のボンボニエールGin no BonboniereJapanese (The Silver Bonbonnière) by Shufu no Tomo-sha in 1991, it was later reissued as 銀のボンボニエール-親王の妃としてGin no Bonboniere - Shin'nō no Hi to ShiteJapanese (The Silver Bonbonnière - As a Prince's Consort) by Kodansha +α Bunko in 1994. The English translation, The Silver Drum: A Japanese Imperial Memoir, was published posthumously in May 1996, translated by Dorothy Britton. This memoir provides valuable perspectives on her personal life, her duties as an imperial princess, and her observations of major historical events.

Princess Setsuko also co-authored 思い出の昭和天皇 おそばで拝見した素顔の陛下Omoide no Showa Tenno: Osoba de Haijken Shita Sugao no HeikaJapanese (Emperor Shōwa in My Memories: The Emperor's True Face I Saw Up Close) published by Kobunsha Kappa Books in December 1989. This work offers her recollections of Emperor Shōwa, providing a personal perspective on the monarch she served alongside for many decades.

Additionally, some of her essays and discussions are included in collected works. For instance, her essay "アメリカの思い出America no OmoideJapanese" ("Memories of America") is featured in 秩父宮談話集 皇族に生まれてⅡChichibunomiya Danwashu Kōzoku ni Umarete IIJapanese ("Collected Discourses of Prince Chichibu: Born into the Imperial Family II"), published by Watanabe Shuppan in 2008. This essay is an excerpt from her earlier work, 御殿場清話Gotemba SeiwaJapanese ("Pure Stories from Gotemba"), which was compiled from interviews by Takeshi Yanagisawa and published in 1948.

8. Honours

Princess Setsuko received numerous national and international decorations and honorary titles throughout her life, reflecting her status and contributions.

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Crown, 1st Class (September 28, 1928)

- 2600th Imperial Era Celebration Commemorative Medal (August 15, 1940)

- Dame Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (United Kingdom)

- Member of the Order of the Seraphim (Sweden, April 8, 1969)

- Honorary Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (United Kingdom, July 23, 1962)

9. Family and Ancestry

Princess Setsuko's family background reveals her deep roots in prominent Japanese aristocratic clans, connecting her to both historical power structures and the Imperial Family itself.

9.1. Ancestry and Family Tree

Princess Setsuko's ancestry highlights her lineage from two of Japan's most distinguished aristocratic families: the Matsudaira and Nabeshima clans.

| Setsuko, Princess Chichibu | ||

|---|---|---|

| Father: Tsuneo Matsudaira | Paternal Grandfather: Matsudaira Katamori, 9th Lord of Aizu | Paternal Great-Grandfather: Matsudaira Yoshitatsu, 10th Lord of Takasu Domain |

| Paternal Great-Grandmother: Chiyoko Komori | ||

| Paternal Grandmother: Nagako Kawamura | Paternal Great-Grandfather: Gembei Kawamura | |

| Paternal Great-Grandmother: Unknown | ||

| Mother: Nobuko Nabeshima | Maternal Grandfather: Marquess Naohiro Nabeshima, 11th Lord of Saga Domain | Maternal Great-Grandfather: Nabeshima Naomasa, 10th Lord of Saga |

| Maternal Great-Grandmother: Tatsuko Tokugawa | ||

| Maternal Grandmother: Nagako Hirohashi | Maternal Great-Grandfather: Taneyasu Hirohashi | |

| Maternal Great-Grandmother: Yone | ||

Her immediate family also maintained close ties to other prominent lines. Her elder sister, Itsuko, married Prince Morimasa Nashimoto, an uncle of Empress Kōjun. Her younger brother, Matsudaira Ichirō, who served as chairman of The Bank of Tokyo, married Toyoko Tokugawa, a daughter of Tokugawa Iemasa, the 17th head of the Tokugawa clan. Through this marriage, Matsudaira Ichirō became the father of Tokugawa Tsunenari, the 18th head of the Tokugawa clan, further cementing Princess Setsuko's family connections to the highest echelons of Japanese society. Princess Setsuko was also a fourth cousin to Princess Kikuko Takamatsu, wife of Prince Takamatsu, as their respective grandfathers, Matsudaira Katamori and Tokugawa Yoshinobu, were second cousins.

9.2. Patrilineal Descent

Princess Setsuko's patrilineal descent traces her lineage back through her father's side, primarily through the Matsudaira clan, a branch of the Tokugawa clan. While the direct link between the Nitta clan and the Tokugawa/Matsudaira clan remains somewhat debated by modern historians, the traditional tracing of her descent is as follows:

- Descent prior to Emperor Keitai is traditionally traced back patrilineally to Emperor Jimmu.

- Emperor Keitai, c. 450-534

- Emperor Kinmei, 509-571

- Emperor Bidatsu, 538-585

- Prince Oshisaka, c. 556-???

- Emperor Jomei, 593-641

- Emperor Tenji, 626-671

- Prince Shiki, ????-716

- Emperor Kōnin, 709-786

- Emperor Kanmu, 737-806

- Emperor Saga, 786-842

- Emperor Ninmyō, 810-850

- Emperor Montoku, 826-858

- Emperor Seiwa, 850-881

- Prince Sadazumi, 873-916

- Minamoto no Tsunemoto, 894-961

- Minamoto no Mitsunaka, 912-997

- Minamoto no Yorinobu, 968-1048

- Minamoto no Yoriyoshi, 988-1075

- Minamoto no Yoshiie, 1039-1106

- Minamoto no Yoshikuni, 1091-1155

- Minamoto no Yoshishige, 1114-1202

- Nitta Yoshikane, 1139-1206

- Nitta Yoshifusa, 1162-1195

- Nitta Masayoshi, 1187-1257

- Nitta Masauji, 1208-1271

- Nitta Motouji, 1253-1324

- Nitta Tomouji, 1274-1318

- Nitta Yoshisada, 1301-1338

- Nitta Yoshimune, 1331?-1368

- Tokugawa Chikasue?, ????-???? (speculated)

- Tokugawa Arichika, ????-????

- Matsudaira Chikauji, d. 1393?

- Matsudaira Yasuchika, ????-14??

- Matsudaira Nobumitsu, c. 1404-1488/89?

- Matsudaira Chikatada, 1430s-1501

- Masudaira Nagachika, 1473-1544

- Matsudaira Nobutada, 1490-1531

- Matsudaira Kiyoyasu, 1511-1536

- Matsudaira Hirotada, 1526-1549

- Tokugawa Ieyasu, 1st Tokugawa Shōgun (1543-1616)

- Tokugawa Yorifusa, 1st Lord of Mito (1603-1661)

- Matsudaira Yorishige, 1st Lord of Takamatsu (1622-1695)

- Matsudaira Yoriyuki, 1661-1687

- Matsudaira Yoritoyo, 3rd Lord of Takamatsu (1680-1735)

- Tokugawa Munetaka, 4th Lord of Mito (1705-1730)

- Tokugawa Munemoto, 5th Lord of Mito (1728-1766)

- Tokugawa Harumori, 6th Lord of Mito (1751-1805)

- Matsudaira Yoshinari, 9th Lord of Takasu (1776-1832)

- Matsudaira Yoshitatsu, 10th Lord of Takasu (1800-1862)

- Matsudaira Katamori, 9th Lord of Aizu (1836-1893)

- Tsuneo Matsudaira, 1877-1949

- Setsuko Matsudaira, 1909-1995