1. Overview

Samuel de Champlain was a pivotal French explorer, navigator, cartographer, and diplomat, widely recognized as the "Father of New France." He played a crucial role in the establishment of French presence in North America, particularly through the founding of Quebec City in 1608. Over his career, he undertook numerous voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, mapping extensive territories, establishing colonial settlements, and fostering complex relationships with various Indigenous nations. His meticulous records and detailed maps significantly contributed to European understanding of the North American continent. Champlain's enduring legacy is evident in the lasting impact he had on Canadian history, influencing its cultural, political, and geographical development, and shaping the early interactions between European settlers and Native American communities.

2. Early Life and Background

Samuel de Champlain's early life and background were shaped by a family of mariners and a period of military service, providing him with the foundational skills necessary for his future endeavors in exploration and colonization.

2.1. Birth and Youth

Samuel de Champlain was born to Antoine Champlain and Marguerite Le Roy, in either Hiers-Brouage or the port city of La Rochelle, in the French province of Aunis. The exact year of his birth remains a subject of historical debate. While some historians, like Pierre-Damien Rainguet and Abbé Charles-Honoré Cauchon Laverdière, estimated his birth year as 1567 or 1570, based on calculations now considered incorrect, a more recent baptism record suggests he was born on or before August 13, 1574. Despite this, the 1567 date was widely accepted for a long time and is inscribed on many monuments. Historian Jean Liebel's research from 1978 suggests Champlain was born around 1580 in Brouage. Champlain himself claimed to be from Brouage in the title of his 1603 book and "Saintongeois" in his 1613 book, referring to the region of Saintonge, where Brouage is located. His family was Roman Catholic, and Brouage was a royal fortress, with Cardinal Richelieu serving as its governor from 1627 until Champlain's death.

Born into a family of mariners, with both his father and uncle-in-law being sailors or navigators, Champlain acquired practical skills in navigation, drawing, and chart-making, as well as writing reports. Unlike many educated individuals of his time, his schooling did not include Ancient Greek or Latin, meaning he did not engage with ancient literature.

2.2. Military Service in France

Champlain gained practical knowledge and combat experience by serving in the army of King Henry IV of France during the latter stages of France's religious wars. His military career began around 1593 or 1594 in Brittany and lasted until 1598, initially as a quartermaster responsible for the logistics and care of horses. During this period, he claimed to have undertaken a "certain secret voyage" for the king and participated in combat, possibly including the Siege of Fort Crozon at the end of 1594. By 1597, he held the rank of "capitaine d'une compagnie" serving in a garrison near Quimper. This military background provided him with valuable experience in organization and strategy, which would later prove essential in his colonial endeavors.

3. Early Voyages and Explorations

Champlain's early travels broadened his understanding of global affairs and the Americas, laying the groundwork for his significant contributions to the exploration and colonization of New France.

3.1. Voyage to the West Indies (1599-1601)

In 1598, following the end of France's religious wars, Champlain embarked on a journey with his uncle-in-law, a navigator whose ship, the Saint-Julien, was tasked with transporting Spanish troops back to Cádiz under the Treaty of Vervins. After a challenging crossing, Champlain spent time in Cádiz before his uncle's ship was chartered to accompany a large Spanish fleet to the West Indies. Champlain joined this voyage, and his uncle entrusted him with overseeing the ship. This two-year journey, spanning from 1599 to 1601, allowed Champlain to observe and learn about Spanish holdings across the Caribbean to Mexico City. During this period, he kept detailed notes and compiled an illustrated, secret report for King Henry IV, who rewarded him with an annual pension. In this report, he even speculated on the idea of a canal through Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, a vision that would be realized over three centuries later with the construction of the Panama Canal.

This report was first published in 1870 as Brief Discours des Choses plus remarquables que Samuel Champlain de Brouage a reconneues aux Indes Occidentalles au voiage qu'il en a faict en icettes en l'année 1599 et en l'année 1601, comme ensuite, and in English as Narrative of a Voyage to the West Indies and Mexico 1599-1602. While the authenticity of this account as Champlain's own work was debated due to some inaccuracies, recent scholarship generally supports his authorship. Upon his return to Cádiz in August 1600, Champlain took charge of his ailing uncle's business affairs. Following his uncle's death in June 1601, Champlain inherited a substantial estate, including property near La Rochelle, commercial assets in Spain, and a 150-ton merchant ship. This inheritance, combined with the king's pension, granted Champlain considerable financial independence, freeing him from reliance on merchants and investors for his future explorations. From 1601 to 1603, he served as a geographer at King Henry IV's court, traveling to French ports and learning about North America from fishermen who seasonally visited coastal areas from Nantucket to Newfoundland. He also studied the failures of previous French colonization attempts, such as Pierre de Chauvin's at Tadoussac.

3.2. First Expeditions to North America (1603-1607)

Champlain's first voyage to North America occurred in 1603 as an observer on a fur-trading expedition led by François Gravé Du Pont, a seasoned navigator and merchant. Du Pont, who became a lifelong friend and mentor, educated Champlain on North American navigation, particularly along the Saint Lawrence River, and on interactions with Indigenous peoples. The expedition's ship, the Bonne-Renommée, arrived at Tadoussac on March 15, 1603. Champlain was eager to explore and map the regions previously described by Jacques Cartier and to venture even further. He created a detailed map of the Saint Lawrence River during this journey. Upon his return to France on September 20, he published an account titled Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603. This account documented his meetings with Begourat, chief of the Montagnais at Tadoussac, establishing positive relationships between the French and the Montagnais and their Algonquin allies. The Indigenous peoples provided guidance, speaking of a "great sea" to the west, which Champlain initially hoped was the Pacific Ocean or the Northwest Passage, but which later proved to be the Great Lakes.

Promising further discoveries to King Henry IV, Champlain joined a second expedition to New France in the spring of 1604. This multi-year journey, without women or children, focused on areas south of the St. Lawrence River, in what became Acadia. It was led by Pierre Dugua de Mons, a noble and Protestant merchant who held a fur-trading monopoly granted by the king. Dugua tasked Champlain with finding a suitable site for a winter settlement. After exploring sites in the Bay of Fundy, Champlain selected Saint Croix Island in the St. Croix River. Following a harsh winter on the island, the settlement was moved across the bay to establish Port Royal in 1605, which later became the capital of Acadia. Champlain used Port Royal as his base until 1607, during which he explored the Atlantic coast. Dugua de Mons's monopoly was rescinded in July 1607 due to pressure from other merchants, leading to the abandonment of the Port Royal settlement and Champlain's return to France.

In 1605 and 1606, Champlain continued his coastal explorations southward to Cape Cod, seeking locations for permanent settlements. Minor skirmishes with the resident Nausets dissuaded him from establishing a settlement near present-day Chatham, Massachusetts, an area he named Mallebar ("bad bar") or "Port Fortune".

4. Founding of Quebec

The founding of Quebec City in 1608 was a pivotal moment in French colonization, establishing a strategically important settlement for the fur trade and future expansion.

4.1. Establishment of the Habitation

In the spring of 1608, Pierre Dugua de Mons directed Champlain to establish a new French colony and fur-trading center along the shores of the St. Lawrence River. Dugua financed a fleet of three ships, manned by workers, which departed from the French port of Honfleur. Champlain commanded the main ship, the Don-de-Dieu (meaning "Gift of God"), while his friend François Gravé Du Pont commanded another, the Lévrier (meaning "Hunt Dog"). The group of male settlers arrived at Tadoussac in June. Due to the dangerous currents where the Saguenay River meets the St. Lawrence, they disembarked and continued upstream in smaller boats with their men and supplies.

Champlain arrived at the chosen site, known by the Indigenous peoples as "Quebec" (meaning "the narrowing of the waters"), on July 3, 1608. He described it as the most convenient and suitable place, covered with nut-trees. He immediately ordered his men to cut down these trees for the construction of their first settlement, known as the "Habitation." This fortified post, later to become Quebec City, became a central passion for Champlain throughout his life.

The first winter for the colonists was exceptionally harsh. Of the 28 men who remained, only eight survived, with most succumbing to scurvy and others to smallpox and severe cold. Days after his arrival, Champlain faced an internal conspiracy led by Jean du Val, a member of his party, who plotted to kill Champlain and seize the settlement for Basque or Spanish interests, aiming to profit himself. The plot was uncovered when an accomplice confessed to Champlain's pilot. Champlain orchestrated the arrest of Du Val and three co-conspirators by inviting them to a gathering on a boat. Du Val was subsequently strangled and hanged in Quebec, his head displayed prominently as a warning, while the other three were sent back to France for trial.

5. Relations and Conflicts with Indigenous Peoples

Champlain's interactions with various Native American tribes, marked by both alliances and conflicts, profoundly influenced the early development of New France and established enduring patterns of relationships.

5.1. Alliances and Early Battles (1609-1610)

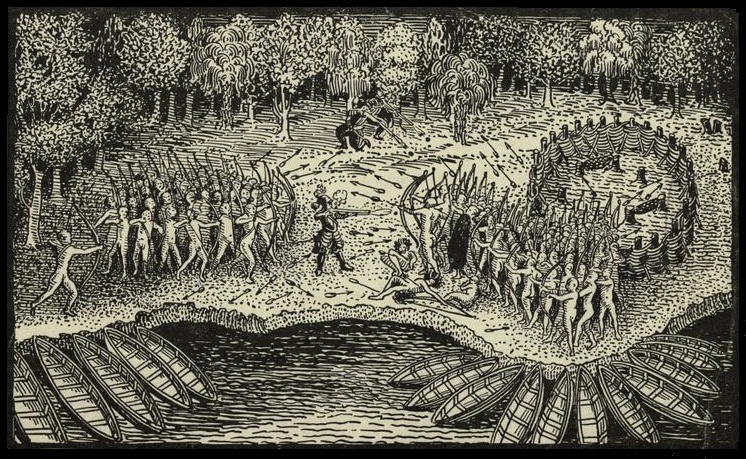

During the summer of 1609, Champlain actively sought to forge stronger relationships with the local First Nations tribes. He established crucial alliances with the Wendat (whom the French called "Huron"), and with the Algonquin, the Montagnais, and the Etchemin, all of whom resided in the St. Lawrence River valley. These tribes sought Champlain's military assistance in their ongoing conflicts against the Iroquois Confederacy, who lived to the south.

Champlain led an expedition with nine French soldiers and 300 Indigenous allies to explore the Rivière des Iroquois (now known as the Richelieu River). During this journey, he became the first European to map Lake Champlain. As they encountered no Iroquois, many of his Indigenous allies turned back, leaving Champlain with only two Frenchmen and 60 Indigenous warriors.

On July 29, 1609, near what is now Ticonderoga or Crown Point, New York, Champlain's party encountered a group of Haudenosaunee. The following day, about 250 Haudenosaunee warriors advanced towards Champlain's position. At a signal from his Indigenous guide, Champlain fired his arquebus, killing two Iroquois chiefs with a single shot, while one of his men killed a third. The Iroquois forces promptly fled. While this initial encounter temporarily deterred the Iroquois, they would later resume hostilities, engaging the French and Algonquin in conflicts that lasted throughout the century, notably the Beaver Wars. A significant peace treaty, the Great Peace of Montreal, was eventually signed in 1701 between the French and most Indigenous nations along the St. Lawrence River.

Another notable engagement, the Battle of Sorel, took place on June 19, 1610, near present-day Sorel-Tracy, Quebec. Champlain, supported by the Kingdom of France and his allies-the Wendat, Algonquin, and Innu peoples-faced the Mohawk people. Champlain's forces, armed with arquebuses, successfully engaged the Mohawks, killing or capturing nearly all of them. This victory significantly reduced hostilities with the Mohawks for the next two decades.

6. Further Explorations of New France

Champlain's extensive inland expeditions greatly expanded European knowledge and mapping of the vast territories of New France beyond its initial coastal settlements.

6.1. Inland Journeys (1613-1615)

On March 29, 1613, upon returning to New France, Champlain first ensured that his new royal commission was formally proclaimed. He then set out on May 27 to continue his exploration of the Huron country, hoping to find a "northern sea" he had heard about, likely referring to Hudson Bay. He traveled along the Ottawa River, providing the first European descriptions of this region. During this journey, he reportedly lost or left behind a collection of silver cups, copper kettles, and a brass astrolabe dated 1603. This astrolabe was later found in 1867 by a farm boy named Edward Lee near Cobden, Ontario. However, modern scholars have since questioned Champlain's ownership of this particular astrolabe.

In June 1613, Champlain met with Tessouat, the Algonquin chief of Allumettes Island. Champlain offered to construct a fort for the Algonquin tribe if they agreed to relocate from their area of poor soil to the locality of the Lachine Rapids. By August 26, Champlain had returned to Saint-Malo, where he wrote an account of his life from 1604 to 1612 and his journey up the Ottawa River, titled Voyages. He also published another map of New France. In 1614, he established the "Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo" and "Compagnie de Champlain," binding merchants from Rouen and Saint-Malo for eleven years in fur trade. He returned to New France in the spring of 1615 with four Recollects to further religious life in the burgeoning colony. The Roman Catholic Church was eventually granted significant land holdings, estimated at nearly 30% of all lands granted by the French Crown in New France, under the seigneurial system.

In 1615, Champlain reunited with Étienne Brûlé, his skilled interpreter, after separate four-year explorations. Brûlé reported on his North American journeys, including an expedition with another French interpreter, Grenolle, along the north shore of la mer douce (the calm sea), now known as Lake Huron, to the great rapids of Sault Ste. Marie, where Lake Superior flows into Lake Huron. Some of these explorations were documented by Champlain. Champlain continued to cultivate relations with Indigenous peoples, promising to assist them against the Iroquois. With his Indigenous guides, he explored further up the Ottawa River and reached Lake Nipissing. He then followed the French River until he arrived at Lake Huron, becoming the first European to formally describe these regions. In 1615, a group of Wendat escorted Champlain through what is now Peterborough, Ontario. He utilized the ancient portage between Chemong Lake and Little Lake (now Chemong Road) and briefly stayed near present-day Bridgenorth, Ontario.

6.2. Military Expedition Against the Iroquois (1615)

On September 1, 1615, at Cahiagué, a Wendat community on what is now Lake Simcoe, Champlain joined an allied military expedition against the Iroquois. The party traversed the eastern tip of Lake Ontario, where they concealed their canoes and continued their journey by land. They followed the Oneida River until they reached the main Onondaga fort on October 10. The precise location of this fort remains debated, though Nichols Pond, about 6.2 mile (10 km) south of Canastota, New York, is a traditional but frequently disproved site. Champlain, accompanied by 10 Frenchmen and 300 Wendat, launched an assault on the stockaded Oneida village. However, pressured by the Wendat to attack prematurely, the assault failed. Champlain was wounded twice in the leg by arrows, one striking his knee. The conflict concluded on October 16 when the French and Wendat forces were compelled to retreat.

Despite his reluctance, the Wendat insisted that Champlain spend the winter with them. During this time, he participated in their extensive deer hunt, during which he became lost for three days, surviving on game and sleeping under trees before fortuitously rejoining a band of First Nations people. He dedicated the remainder of the winter to learning about "their country, their manners, customs, modes of life." On May 22, 1616, he departed the Wendat country, returned to Quebec, and then sailed back to France on July 2.

7. Personal Life

Samuel de Champlain's personal life, including his marriage and the adoption of children, offers a glimpse into the private aspects of a figure otherwise consumed by exploration and colonial administration.

7.1. Marriage to Hélène Boullé

Champlain sought to strengthen his ties to the regent's court by marrying Hélène Boullé, the twelve-year-old daughter of Nicolas Boullé, a court official responsible for executing royal decisions. The marriage contract was signed on December 27, 1610, in the presence of Dugua de Mons, who had negotiated with Hélène's father. The couple was married three days later; Champlain was 43 years old at the time. The contract stipulated that the marriage would be consummated two years later. Although their relationship was initially troubled, with Hélène resisting joining him in August 1613, it later recovered and remained stable for many years, despite apparently lacking a physical connection. Hélène lived in Quebec for several years before returning to Paris and eventually entering a convent. The couple had no biological children.

7.2. Adopted Children

In the winter of 1627-1628, Champlain adopted three young Montagnais girls, whom he named Faith, Hope, and Charity. This act provides a rare insight into his personal connections with the Indigenous communities and his engagement with their people beyond diplomacy and conflict.

8. Administration of New France and Later Years

Champlain's role evolved significantly from explorer to dedicated administrator, as he faced political and military challenges in consolidating and developing the French colony in North America.

8.1. Shift to Administrative Role

In 1620, Louis XIII ordered Champlain to cease further explorations, return to Quebec, and dedicate himself solely to the administration and development of New France. Champlain spent the winter constructing Fort Saint-Louis atop Cape Diamond in Quebec City. In mid-May, he discovered that the fur trading monopoly had been transferred to a rival company led by the Caen brothers. After tense negotiations, the two companies merged under the direction of the Caens. Champlain continued his efforts to improve relations with Indigenous peoples, even managing to appoint a chief of his choosing, and successfully negotiated a peace treaty with the Iroquois.

Champlain persistently worked on fortifying Quebec City, laying the first stone of its expanded defenses on May 6, 1624. On August 15, he once again returned to France, where he was encouraged to continue his work in New France and to persist in searching for a passage to China, which was widely believed to exist at the time. By July 5 of the following year, he was back in Quebec, overseeing the continued expansion of the city.

In 1627, the Caen brothers' company lost its monopoly on the fur trade. Cardinal Richelieu, who had rapidly risen to a dominant position in French politics, formed the Company of One Hundred Associates to manage the fur trade and lead the colonization efforts. Champlain was one of the 100 investors in this new company, and its first fleet, carrying colonists and supplies, set sail in April 1628.

8.2. Capture and Restoration of Quebec (1628-1632)

Champlain had spent the winter in Quebec, where supplies were critically low. In July 1628, English merchants sacked Cap Tourmente. A war had erupted between France and England, and Charles I of England had issued letters of marque authorizing the capture of French shipping and North American colonies. On July 10, Champlain received a summons to surrender from the Kirke brothers, two Scottish brothers in the service of the English government. Champlain, despite having only 50 lb (50 lb) of gunpowder, successfully bluffed the Kirkes into believing Quebec's defenses were stronger than they were, causing them to withdraw temporarily. However, they later intercepted and captured the French supply fleet, cutting off vital provisions for the colony that year.

By the spring of 1629, supplies were dangerously depleted, forcing Champlain to send colonists to Gaspé and into Indigenous communities to conserve rations. On July 19, the Kirke brothers returned to Quebec, having intercepted Champlain's desperate plea for aid. Champlain was compelled to surrender the colony. Many colonists were transported to England and then to France by the Kirkes, but Champlain remained in London to initiate the process of regaining the colony for France. A peace treaty had actually been signed in April 1629, three months before Quebec's surrender. Under the terms of this Treaty of Susa, Quebec and other prizes captured by the Kirkes after the treaty's signing were to be returned. However, it was not until the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye that Quebec was formally returned to France. (David Kirke was later knighted by Charles I and granted a charter for Newfoundland.) Champlain formally reclaimed his role as commander in New France on behalf of Richelieu on March 1, 1633, having served as commander "in the absence of my Lord the Cardinal de Richelieu" from 1629 to 1635. In 1632, Champlain published Voyages de la Nouvelle-France, dedicated to Cardinal Richelieu, and Traitté de la marine et du devoir d'un bon marinier, a treatise on leadership, seamanship, and navigation. Throughout his lifetime, Champlain made more than 25 round-trip crossings of the Atlantic without losing a single ship.

8.3. Final Administrative Period (1633-1635)

Champlain returned to Quebec on May 22, 1633, after a four-year absence. Richelieu appointed him as Lieutenant General of New France, along with other titles and responsibilities, though he was not formally given the title of governor. Despite this lack of formal status, many colonists, French merchants, and Indigenous peoples regarded and treated him as if he held the title, often referring to him in writings as "our governor." On August 18, 1634, he submitted a report to Richelieu, detailing his efforts to rebuild Quebec from its ruins, expand its fortifications, and establish two new habitations: one 15 leagues upstream and another at Trois-Rivières. He also initiated an offensive against the Iroquois, expressing his desire to see them either "wiped out" or "brought to reason," reflecting the ongoing complexities and conflicts in French-Indigenous relations during his final years.

9. Death and Burial

Samuel de Champlain's life came to an end in Quebec, and the circumstances surrounding his death and the mystery of his final resting place have intrigued historians for centuries.

9.1. Death in Quebec

Champlain suffered a severe stroke in October 1635. He died on December 25, 1635, on Christmas Day, in Quebec, leaving no immediate heirs. Jesuit records indicate that he passed away under the care of his friend and confessor, Charles Lallemant. Although his will, drafted on November 17, 1635, bequeathed a significant portion of his French property to his wife, Hélène Boullé, he also made substantial bequests to Catholic missions and individuals within the colony of Quebec. However, his cousin, Marie Camaret, a relative on his mother's side, challenged the will in Paris, leading to its overturning. The precise fate of his estate remains unclear.

9.2. Unlocated Burial Site

Samuel de Champlain was initially interred temporarily in the church while a dedicated, standalone chapel was being constructed to house his remains in the upper part of Quebec City. This small building, along with many others, was tragically destroyed by a large fire in 1640. Although the chapel was rebuilt immediately, no definitive traces of it exist today. Despite extensive research conducted since the mid-19th century, including several archaeological digs within the city, his exact burial site remains unknown. There is a general historical consensus that the former site of Champlain's chapel, and consequently his remains, should be located somewhere near the Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral. The search for Champlain's remains serves as a key plotline in Louise Penny's 2010 crime novel, Bury Your Dead.

10. Legacy and Commemoration

Samuel de Champlain's enduring legacy as the "Father of New France" is marked by his profound impact on North American history, influencing cartography, ethnology, and diplomacy, and inspiring numerous tributes and monuments across the continent.

10.1. Historical Impact

Champlain is widely memorialized as the "Father of New France" and the "Father of Acadia." His historical significance continues to resonate in modern times due to his pivotal role in expanding French influence in North America. He was a master cartographer, producing the first accurate coastal maps of the region and detailed maps of the Saint Lawrence River, the Great Lakes, and surrounding territories. His meticulous written accounts, including Des Sauvages and Voyages de la Nouvelle-France, offered invaluable ethnographic observations on the Indigenous peoples he encountered, detailing their customs, manners, and modes of life. These works provided Europeans with their earliest comprehensive descriptions of North American geography and its diverse Native populations. His diplomatic efforts, while sometimes leading to conflict, forged crucial alliances with various Indigenous nations that were essential for the survival and growth of the early French colony. Champlain's vision and tireless work in establishing settlements like Quebec City laid the permanent foundations for French colonization and profoundly influenced the cultural and political development of what would become Canada. At the time of his death, New France had nearly 300 French settlers; today, Quebec alone has a population exceeding 7 million French-speaking inhabitants, with Quebec City remaining its thriving capital.

q=Quebec City|position=right

10.2. Tributes and Monuments

Many sites and landmarks across North America honor Samuel de Champlain, reflecting his prominence in regions such as Acadia, Ontario, Quebec, New York, and Vermont. Most notably, Lake Champlain, which spans the border between northern New York and Vermont and extends into Canada, was named by him in 1609 when he explored it as part of an expedition along the Richelieu River. He was the first European to map and describe this long, narrow lake situated between the Green Mountains and the Adirondack Mountains.

Geographical features named in his honor include the Champlain Valley, the Champlain Trail Lakes, and the ancient Champlain Sea, a prehistoric inlet of the Atlantic Ocean over the St. Lawrence, Saguenay, and Richelieu rivers that disappeared millennia before his birth. Champlain Mountain in Acadia National Park was first observed by him in 1604. Towns and municipalities bearing his name include Champlain and Champlain village in New York, a township in Ontario, and a municipality in Quebec. Several provincial electoral districts in Quebec have also been named after him, as well as Samuel de Champlain Provincial Park in northern Ontario.

Numerous functional structures and institutions bear his name, including the Champlain Bridge connecting Montreal Island to Brossard, Quebec across the St. Lawrence, and the Champlain Bridge linking Ottawa, Ontario and Gatineau, Quebec. Educational institutions include Champlain College at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, Fort Champlain (a dormitory) at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario, École Champlain in Saint John, New Brunswick and Moncton, New Brunswick (and Brossard), Champlain College in Burlington, Vermont, and Champlain Regional College (a CEGEP) with three campuses in Quebec. The Marriott Château Champlain hotel in Montreal also carries his name.

Streets named Champlain are found in numerous cities, such as Quebec City, Shawinigan, Dieppe, Plattsburgh, and several communities in northwestern Vermont. A garden, Jardin Samuel-de-Champlain, is located in Paris, France.

Various statues and monuments commemorate Champlain. These include:

- A memorial statue on Cumberland Avenue in Plattsburgh, New York, on the shores of Lake Champlain.

- A memorial statue in Saint John, New Brunswick, in Queen Square, commemorating his discovery of the Saint John River.

- A memorial statue in Isle La Motte, Vermont, on the shore of Lake Champlain.

- The lighthouse at Crown Point, New York, which features a statue of Champlain by Carl Augustus Heber.

- A statue in Ticonderoga, New York, unveiled in 2009 for the 400th anniversary of his exploration of Lake Champlain.

- A statue in Orillia, Ontario, at Couchiching Beach Park on Lake Couchiching, which was removed by Parks Canada due to offensive depictions of First Nations peoples and is unlikely to be returned.

- A memorial statue at Kìwekì Point in Ottawa, sculpted by Hamilton MacCarthy. This statue depicts Champlain holding an astrolabe, though it is controversially depicted upside-down. It originally included an "Indian Scout" kneeling at its base, but after lobbying by Indigenous people in the 1990s, this figure was removed and renamed the "Anishinaabe Scout", now located in Major's Hill Park.

Other tributes include a joint commemorative stamp issue by the United States Postal Service and Canada Post in May 2006. Two ships of the Royal Canadian Navy have been named HMCS Champlain: an S class destroyer from 1928 to 1936, and a Naval Reserve division activated in 1985 in Chicoutimi, Quebec. Champlain Place, a shopping center in Dieppe, New Brunswick, and The Champlain Society, a Canadian historical and text publication society chartered in 1927, also bear his name.