1. Life

René Descartes's life was marked by a quest for knowledge and certainty, leading him through various educational institutions, military service, and periods of intense intellectual work, primarily in the Dutch Republic, before his final years in Sweden.

1.1. Early Life and Education

René Descartes was born on March 31, 1596, in La Haye en Touraine, a small town in the Touraine province of France, which is now named Descartes in his honor. He was the third child of his family, which belonged to the legal nobility; his father, Joachim Descartes, was a councilor in the Parlement of Rennes in Brittany. His mother, Jeanne Brochard, died less than 14 months after his birth, following the delivery of a stillborn child. He was subsequently raised by his maternal grandmother and a wet nurse. Descartes was known for his strong curiosity about objects around him and a habit of deep thought in quiet places. His father, recognizing his philosophical inclination, nicknamed him "the little philosopher." Despite growing up in a Catholic household, his birthplace in the Poitou region was a stronghold of Huguenot influence.

Due to his fragile health, Descartes began his formal education somewhat late, entering the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche in 1607, where he studied for eight years until 1614. The Collège, founded by King Henry IV of France and managed by Jesuits, was known for its rigorous curriculum, which included Latin, rhetoric, classical authors, dialectics, natural philosophy, metaphysics, and ethics. It was here that Descartes was introduced to mathematics and physics, including the works of Galileo Galilei. The College celebrated Galileo's discovery of Jupiter's moons in 1610, indicating an openness to new scientific ideas despite its scholastic framework. However, philosophy was primarily seen as a preparatory study for theology, with uncertain philosophical truths being completed by theology. Descartes was a diligent and gifted student, particularly excelling in mathematics, where he often used mathematical methods in philosophical debates. He read widely, including texts on astrology and magic. During this period, he developed skepticism towards the non-rigorous and probabilistic nature of theology and scholasticism compared to the certainty of mathematics. Nevertheless, he remained grateful to the College and its teachers throughout his life.

After graduating in 1614, Descartes pursued legal and medical studies at the University of Poitiers for two years, earning a Baccalauréat and a Licence in canon and civil law in 1616, in accordance with his father's wishes for him to become a lawyer. During this period, he studied mathematics, natural science, and scholastic philosophy. He then moved to Paris, where he reconnected with his former schoolmate, Marin Mersenne, and met other notable mathematicians like Claude Mydorge. Despite his legal education, Descartes chose not to practice law, finding Parisian social life unfulfilling. He decided to abandon the study of letters and seek knowledge directly from "the great book of the world," embarking on a period of travel and self-discovery. An anecdote from this period describes him encountering an advertisement for a geometry problem in Dutch and solving it in a few hours, confirming his mathematical talent.

1.2. Military Service and Travels

In 1617, seeking practical knowledge and a change of pace from Parisian life, Descartes joined the Protestant Dutch States Army as a mercenary in Breda under the command of Maurice of Nassau. Although the Eighty Years' War was in a truce, the Dutch army was modernized and engaged in new weapon development, attracting mathematicians and engineers like Simon Stevin. This environment provided Descartes with opportunities to deepen his mathematical knowledge. In November 1618, in Breda, he met Isaac Beeckman, a physician, natural philosopher, and mathematician who held advanced views on atoms, vacuum, and the conservation of motion, and was a supporter of Nicolaus Copernicus. Beeckman's corpuscularian approach to mechanical theory significantly influenced Descartes, convincing him to dedicate his studies to a mathematical approach to nature. They collaborated on problems related to free fall, catenaries, conic sections, and fluid statics, both believing in the necessity of a method that thoroughly linked mathematics and physics. Descartes's first work, the *Compendium of Music*, was dedicated to Beeckman.

In 1619, hearing of the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War, Descartes left the Dutch army, seeking more active military experience. He traveled to Germany, attending the coronation of Emperor Ferdinand II in Frankfurt am Main before joining the army of the Catholic Duke Maximilian of Bavaria. While stationed in Neuburg an der Donau in October 1619, Descartes had a profound intellectual experience. On the night of November 10-11, 1619 (St. Martin's Day), he secluded himself in a room with an "oven" to escape the cold. There, he experienced three vivid dreams, which he interpreted as a divine revelation of a new philosophy. He believed that a divine spirit had inspired him to pursue true wisdom through science and to apply the mathematical method to philosophy. This vision led him to formulate analytic geometry and the idea that all truths are interconnected, meaning that discovering a fundamental truth would open the way to all science. This foundational truth, which he soon arrived at, was his famous "I think, therefore I am." Some modern interpretations suggest his second dream might have been an episode of exploding head syndrome.

After leaving the army in 1620, Descartes traveled through various countries, including a visit to the Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, before returning to France in 1623. He spent several years in Paris, associating with scholars like Mersenne, Thomas Hobbes, and Pierre Gassendi. In 1627, he observed the siege of La Rochelle led by Cardinal Richelieu, studying the physical properties of the great dike being built. He also met French mathematician Girard Desargues. During a gathering at the residence of papal nuncio Giovanni Francesco Guidi di Bagno, where he presented his philosophical ideas, Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle strongly encouraged him to articulate his new philosophy in writing, away from the influence of the Inquisition. This spurred his decision to move to the Netherlands.

1.3. Life in the Netherlands

Descartes returned to the Dutch Republic in 1628, seeking an environment conducive to solitary study and undisturbed intellectual work. He found the Dutch Republic, with its established disciplines and relative freedom, ideal for his "solitary and hidden life." In April 1629, he briefly joined the University of Franeker, studying under Adriaan Metius, and later enrolled at Leiden University in 1630 under the name "Poitevin," studying mathematics with Jacobus Golius and astronomy with Martin van den Hove. His intellectual engagements during this period included a falling out with Isaac Beeckman in October 1630, whom he accused of plagiarizing his ideas.

During his residence in the Netherlands, Descartes had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine, born in 1635 in Deventer. Francine was baptized a Protestant and tragically died of scarlet fever at the age of five in 1640. Descartes was deeply affected by her death, reportedly weeping, and stating that one need not refrain from tears to prove oneself a man. Some scholars, like Russell Shorto, speculate that the experience of fatherhood and loss may have shifted Descartes's focus from medicine to a broader quest for universal answers.

Despite frequent changes of residence within the Netherlands (including Dordrecht, Amsterdam, Leiden, Deventer, Utrecht, Egmond aan den Hoef, Santpoort, Endegeest, and Egmond-Binnen), Descartes produced all of his major philosophical and scientific works during his more than two decades there. In 1633, he abandoned plans to publish his *Treatise on the World* (*Le Monde*), a systematic presentation of his mechanical philosophy, after learning of Galileo's condemnation by the Italian Inquisition for supporting the heliocentric view. Nevertheless, in 1637, he published parts of this work in three essays: "Les Météores" (The Meteors), "La Dioptrique" (Dioptrics), and *La Géométrie* (Geometry), preceded by his famous introduction, *Discours de la méthode* (*Discourse on the Method*). In the *Discourse*, Descartes outlined four rules of thought designed to establish knowledge on a firm foundation, emphasizing clarity and distinctness to avoid prejudice and doubt. *La Géométrie* notably incorporated his discoveries with Pierre de Fermat, laying the groundwork for what became known as Cartesian Geometry.

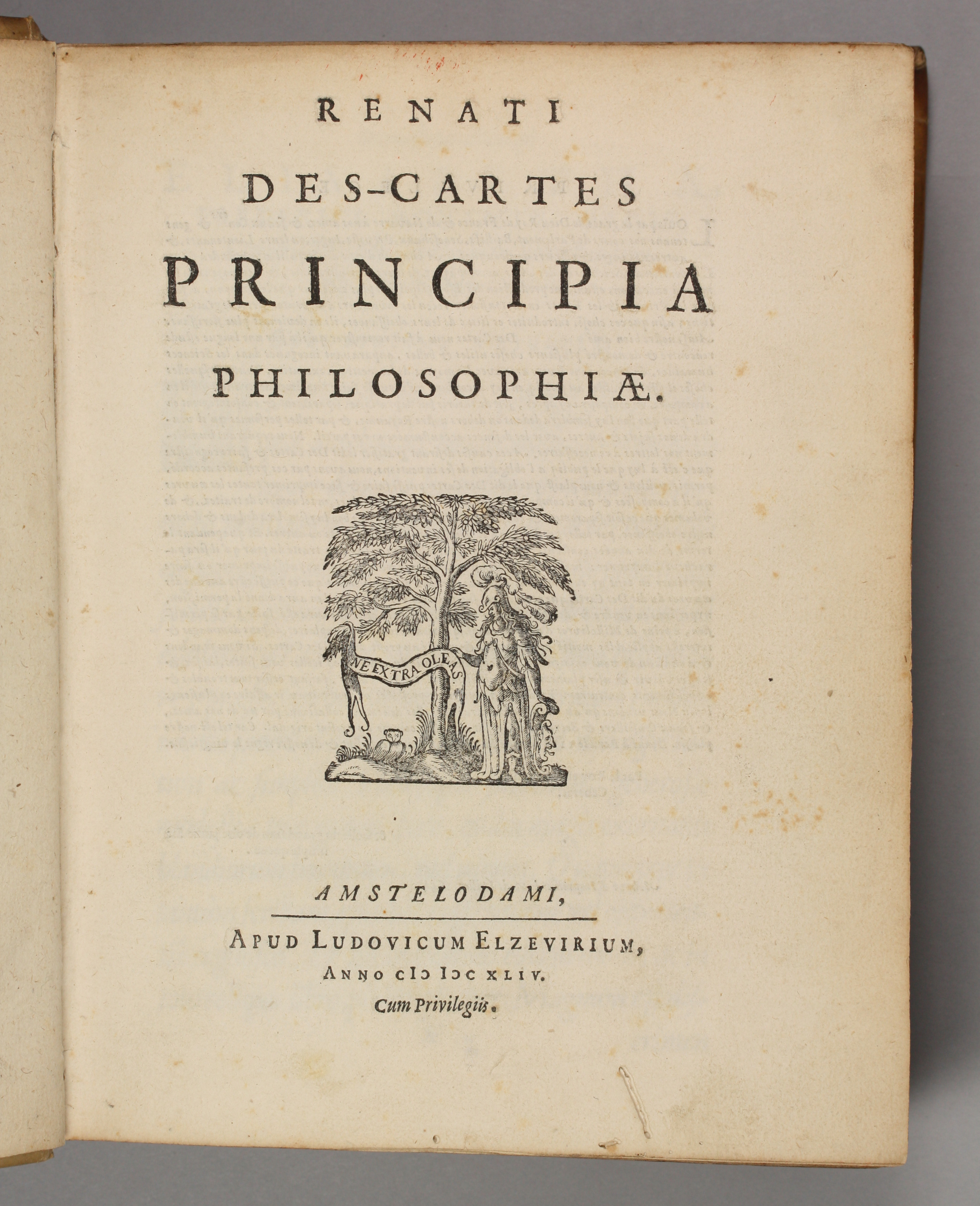

In 1641, Descartes published his metaphysics treatise, *Meditationes de Prima Philosophia* (*Meditations on First Philosophy*), written in Latin for a scholarly audience. This was followed in 1644 by *Principia Philosophiae* (*Principles of Philosophy*), intended as a comprehensive textbook to replace Aristotelian ones in universities. A French translation, *Principes de philosophie*, supervised by Descartes, appeared in 1647 and was dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy faced condemnation at the Utrecht University, forcing Descartes to relocate to The Hague and settle in Egmond-Binnen. Between 1643 and 1649, he resided in an inn in Egmond-Binnen, befriending Anthony Studler van Zurck and contributing to the design of his estate. He also met and was impressed by the mathematician and surveyor Dirck Rembrantsz van Nierop. Descartes engaged in a significant six-year correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, primarily discussing moral and psychological subjects. This correspondence led to his 1649 work, *Les Passions de l'âme* (*The Passions of the Soul*), which was also dedicated to the Princess.

1.4. Later Life and Death in Sweden

By 1649, René Descartes had achieved widespread recognition as one of Europe's foremost philosophers and scientists. In February of that year, Queen Christina of Sweden extended an invitation for him to join her court in Stockholm, with the aim of establishing a new scientific academy and receiving private instruction on his philosophical ideas, including his views on love. Despite the Queen's suggestion to avoid the harsh winter, Descartes departed in September and arrived in Stockholm in October.

He was hosted by Pierre Chanut, the French ambassador, residing on Västerlånggatan, close to Tre Kronor Castle. While there, Descartes and Chanut conducted observations with a Torricellian mercury barometer, taking the first barometric readings in Stockholm to explore the use of atmospheric pressure in weather forecasting, a challenge to Blaise Pascal's work.

Queen Christina arranged for Descartes to give her philosophy lessons three times a week at 5 a.m. in her cold and drafty castle. However, by January 15, 1650, they had met only four or five times. It became apparent that their intellectual interests diverged; Christina found his mechanical philosophy unappealing, and he did not share her enthusiasm for Ancient Greek language and literature. On February 1, 1650, Descartes contracted pneumonia and died on February 11 at Chanut's residence. His last reported words were: "My soul, though has long been held captive. The hour has now come for thee to quit thy prison, to leave the trammels of this body. Then to this separation with joy and courage!"

The official cause of death was pneumonia, or peripneumonia according to Christina's physician Johann van Wullen, whom Descartes had refused treatment from. While the winter was generally mild, the latter half of January was severe, as Descartes himself noted, possibly reflecting both the weather and the intellectual climate. However, some scholars, notably German philosopher Theodor Ebert in a 2009 book, have put forth a theory that Descartes was poisoned by Jacques Viogué, a Catholic missionary who opposed his religious views. Ebert cites a veiled reference to poisoning in Catherine Descartes's (René's niece) 1693 "Report on the Death of M. Descartes, the Philosopher," where she mentions her uncle being administered "communion" two days before his death.

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, Descartes was initially interred in a churchyard in Stockholm, primarily used for orphans. In 1663, the Pope placed Descartes's works on the *Index of Prohibited Books*. In 1666, sixteen years after his death, his remains were transported to France and reburied in Saint-Étienne-du-Mont in Paris. Despite plans by the National Convention in 1792 to transfer his remains to the Panthéon, he was reburied in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1819. However, during these transfers, a finger and the skull were separated from his body. His alleged skull is housed in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, but recent research in 2020 suggests it might be a forgery. The original skull was likely divided into pieces in Sweden and distributed among private collectors, with one piece preserved at the University of Lund since 1691. His epitaph states: "Descartes, the man who first won and secured the right of reason for humanity after the European Renaissance."

2. Philosophical Contributions

Descartes's philosophical contributions are foundational to modern Western thought, characterized by a radical quest for certainty, a distinct separation of mind and body, and a rationalist epistemology that emphasized innate ideas and deductive reasoning. His philosophical work can be understood in the context of the intellectual conflicts of his time, particularly the tension between scholasticism and the emerging Galilean-Copernican science.

2.1. Methodological Doubt and the Cogito

Descartes initiated his philosophical system by employing a method known as Cartesian doubt, also referred to as hyperbolical or metaphysical doubt, or methodological skepticism. This method involved systematically doubting all beliefs that could possibly be doubted, no matter how remote the possibility, to establish a foundation of absolutely certain knowledge. He aimed to discard all preconceived notions and prejudices acquired from childhood without critical examination.

The process of methodological doubt unfolded in stages. First, he rejected knowledge derived from sensory experience, as the senses often deceive (e.g., a straight stick appearing bent in water). Second, he questioned common facts about the world, such as fire being hot or heavy objects falling, by introducing the possibility of dreams; if dreams can be indistinguishable from waking reality, then any sensory experience could be illusory. Finally, he extended his doubt to the very principles of logic and mathematics, proposing the hypothesis of an "evil demon" (*genius malignus*), an all-powerful and cunning deceiver who might be manipulating his thoughts and perceptions, making even seemingly self-evident truths (like 2+3=5) false. This radical doubt was a significant departure from previous philosophers who assumed a direct correspondence between internal representations (*ideas* or *conceptions* as Descartes called them) and external reality.

Through this rigorous process of doubt, Descartes sought to find what, if anything, could not be doubted. He arrived at a single, indubitable truth: the very act of doubting confirms the existence of a doubter. This led to his most famous philosophical statement, "Cogito, ergo sumI think, therefore I amLatin." This phrase, appearing in Latin in *Principles of Philosophy* (1644) and in French ("Je pense, donc je suisFrench") in *Discourse on the Method* (1637), asserts that the act of thinking itself is proof of existence. If he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting, thereby proving his existence. This principle became the bedrock of his philosophy, serving as an absolute and certain starting point. It is worth noting that a similar idea had been proposed by the Spanish philosopher Gómez Pereira a hundred years earlier in the form: "I know that I know something, anyone who knows exists, then I exist" (nosco me aliquid noscere, & quidquid noscit, est, ergo ego sum).

From this foundational truth, Descartes established a general rule for truth: "whatever I perceive clearly and distinctly is true." He concluded that he exists as a "thinking thing" (*res cogitans*), defining "thought" (*cogitatio*) as any activity of which a person is immediately conscious. He argued that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams and that his mind could not be entirely hijacked by an evil demon, as the clear and distinct perception of his own existence and thinking nature was beyond doubt. This marked a shift towards deduction as the primary method for acquiring knowledge, discarding sensory perception as inherently unreliable for foundational truths. Descartes famously stated, "And so something that I thought I was seeing with my eyes is grasped solely by the faculty of judgment which is in my mind."

2.2. Mind-Body Dualism

One of Descartes's most distinctive and influential doctrines is his theory of substance dualism, commonly known as Cartesian dualism or mind-body dualism. This theory posits a fundamental distinction between two radically different kinds of substances that constitute reality: the thinking substance (mind or soul, *res cogitans*) and the extended substance (body or matter, *res extensa*). His conceptualization was influenced by the automatons he observed at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye and by contemporary theological and physical ideas.

According to Descartes, the mind is an un-extended, immaterial, and indivisible substance, whose essential attribute is thought. He argued that "when I consider the mind, or myself in so far as I am merely a thinking thing, I am unable to distinguish any part within myself; I understand myself to be something quite single and complete." In contrast, the body is an extended, material, and divisible substance, whose essential attribute is extension (occupying space with length, breadth, and depth). Sensory qualities like heat, sweetness, or odor are not inherent properties of the body itself but are rather effects produced by the body's interaction with sensory organs.

Descartes maintained that these two substances are "really distinct," meaning each can exist independently of the other. He reasoned that since he could clearly and distinctly conceive of his mind existing without his body, and vice versa, they must be distinct substances. While he gave priority to the mind, arguing it could exist without the body, he also acknowledged that humans are a "composite entity" of mind and body, closely joined. He famously stated that he is "not merely present in my body as a pilot in his ship, but that I am very closely joined and, as it were, intermingled with it, so that I and the body form a unit." He explained this union through the pineal gland in the brain, which he hypothesized as the primary seat of the soul, where mind and body interact. Signals from the senses would travel via "animal spirits" (light, roaming fluids in the nervous system) to the pineal gland, which then influenced the soul's passions and directed bodily movements.

Descartes's dualism provided a philosophical rationale for the emerging modern physics of Kepler and Galileo Galilei, which sought to explain nature through mechanical laws, rejecting the Aristotelian concept of "final causes" or inherent purposes in the physical universe. By confining purpose and consciousness to the mind (*res cogitans*), Descartes effectively "expelled" them from the physical universe (*res extensa*), allowing for a purely mechanistic understanding of the material world. This distinction, while paving the way for modern physics, also left room for religious beliefs, such as the immortality of the soul.

However, this theory also presented a profound challenge: the mind-body problem, specifically how two such fundamentally different substances could causally interact. This question became a central point of debate for subsequent philosophers. Descartes's emphasis on innate ideas-knowledge humans are born with through God's higher power-was later challenged by empiricists like John Locke, who argued that all knowledge is acquired through experience. Descartes further illustrated the limits of sensory perception through his famous wax argument. He considered a piece of wax, noting its sensory qualities (shape, texture, size, color, smell). When brought near fire, these qualities completely change, yet it remains the same wax. Therefore, he concluded, the nature of the wax cannot be understood through the senses but only through the intellect.

2.3. Proofs for the Existence of God

Central to Descartes's project of establishing certainty was his demonstration of God's existence, which served to validate his clear and distinct perceptions and, by extension, the reliability of the external world. He offered two main arguments for God's existence in his *Meditations on First Philosophy*: the trademark argument (or causal argument for God's existence) and the ontological argument.

The **trademark argument** (presented in the Third Meditation) begins with the premise that every effect must have a cause with at least as much reality or perfection as the effect itself (the causal adequacy principle). Descartes identifies within his mind an idea of God, which he defines as a supremely perfect, infinite, omniscient, omnipotent, and benevolent being. He argues that he, a finite and imperfect being, could not have originated such an idea from himself, nor from any other finite source. Therefore, the idea of God must have been "stamped" or "trademarked" upon his mind by a truly infinite and perfect being-God Himself-just as a craftsman leaves a mark on his work. This idea is innate, not derived from sensory experience or imagination.

The **ontological argument** (presented in the Fifth Meditation) is a variation of Anselm's argument. Descartes argues that the very concept of God, as a supremely perfect being, necessarily includes existence as one of His perfections. Just as a triangle's essence necessarily includes having three angles that sum to 180 degrees, God's essence necessarily includes existence. To conceive of a supremely perfect being that lacks existence would be a contradiction in terms, as existence is a perfection. Therefore, if the idea of God is clearly and distinctly perceived, then God must exist.

These proofs were crucial for Descartes because a benevolent, non-deceiving God guarantees the reliability of his clear and distinct perceptions, including those of the external world. If God is perfect and good, He would not allow Descartes to be systematically deceived (as by an evil demon) when he clearly and distinctly perceives something. This divine guarantee allows Descartes to move beyond the radical skepticism of the early meditations and establish the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world through deduction and perception, provided these are based on clear and distinct ideas.

2.4. Epistemology and Rationalism

Descartes is widely considered the "father of modern philosophy" due to his profound impact on Western philosophy, particularly in shifting the focus to epistemology in the 17th century. His epistemological framework is a cornerstone of rationalism, a philosophical school that emphasizes reason as the primary source and ultimate test of knowledge.

Descartes's rationalism is characterized by his reliance on:

- Reason**: He believed that true knowledge is attained through intellectual intuition and deductive reasoning, rather than through unreliable sensory experience. His method of doubt aimed to clear away all uncertain beliefs to arrive at indubitable truths, which could then serve as foundations for further knowledge.

- Innate Ideas**: Descartes argued that certain fundamental ideas, such as the idea of God, the principles of mathematics, and the concept of a thinking self, are not derived from experience but are inherent in the mind from birth. These innate ideas provide the mind with the necessary tools to understand reality.

- Clear and Distinct Perceptions**: For Descartes, a belief is true if and only if it is perceived "clearly and distinctly." A clear perception is one that is present and open to the attending mind, much like seeing an object clearly in bright light. A distinct perception is one that is so precise and different from all other perceptions that it contains nothing but what is clear. The *Cogito, ergo sum* was his prime example of a clear and distinct perception.

He laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, which was later advocated and developed by philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. This school of thought, with its systematic approach to philosophy, significantly influenced modern Western thought, giving the "Age of Reason" its name. While Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz were all well-versed in mathematics and integrated various domains of knowledge into their works, their rationalist approach was later contrasted with the empiricism of thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, George Berkeley, and David Hume, who asserted that all knowledge is derived from sensory experience.

Descartes, however, also recognized the importance of experimentation. While emphasizing deduction from clear and distinct ideas, he acknowledged that empirical verification was necessary to confirm and validate theories about the physical world, especially in fields like physics and medicine.

2.5. Ethics and the Passions of the Soul

For Descartes, ethics was the highest and most perfect of all sciences, deeply rooted in metaphysics. He believed that a complete moral philosophy must include the study of the human body and its interactions with the mind, as the quality of one's reasoning and actions depends on both knowledge and physical condition.

In his *Discourse on the Method*, written during his period of radical doubt, Descartes adopted three "provisional maxims" to guide his actions while he sought to establish certain philosophical foundations:

- To obey the laws and customs of his country, adhering to the most moderate and generally accepted opinions, and maintaining the religion in which he was raised.

- To be firm and resolute in his actions, following even doubtful opinions as if they were certain once a decision was made, to avoid indecision.

- To conquer himself rather than fortune, and to change his desires rather than the order of the world, believing that only his thoughts were entirely within his control.

These maxims were temporary guidelines, allowing him to function morally while his philosophical system was under construction. He later clarified that these provisional rules were not meant to be permanent, as true wisdom would eventually lead to the discovery of correct opinions through one's own judgment.

Descartes's most extensive work on moral philosophy is *The Passions of the Soul*, published in 1649 and dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, with whom he had a significant correspondence on moral and psychological subjects. In this treatise, he analyzed human emotions and their physiological basis. Unlike many moralists of his time who deprecated passions, Descartes defended them as natural and often beneficial. He identified six basic passions: wonder, love, hatred, desire, joy, and sadness. He argued that these passions arise from the interaction between the soul and the body, mediated by the pineal gland and "animal spirits" (fine, fluid particles in the nerves). While passions could distort the soul's commands, he believed that humans could learn to control them through reason and the exercise of free will, striving for a state of "generosity" or "high-mindedness."

His theories on automatic bodily reactions to external events, particularly in *The Passions of the Soul*, significantly influenced 19th-century reflex theory. He described how sensory input could trigger a chain of reactions through the nervous system, leading to automatic bodily responses without conscious thought. This mechanistic view of the body, including its emotional responses, laid a foundation for later physiological theories; Ivan Pavlov, for instance, was a great admirer of Descartes.

Descartes's moral philosophy, with its emphasis on reason and the control of passions, had a lasting impact on subsequent philosophical thought and even influenced ideas about literature and art, particularly concerning how they should evoke emotion. He aligned with Zeno in identifying the sovereign good with virtue, though he acknowledged that external fortunes could contribute to happiness, but emphasized that the mind is fully within one's control.

2.6. Views on Animals

René Descartes held a controversial view on animals, asserting that they were mere mechanical entities, devoid of reason, consciousness, or feeling. He argued that animals did not possess a soul or mind, which he considered necessary for experiencing pain or anxiety. While animals might exhibit behaviors that appear to indicate distress, Descartes explained these as purely mechanistic reactions, similar to a clock or an automaton, rather than genuine expressions of suffering. He believed that any signs of distress were simply automatic bodily responses designed to protect the physical organism from damage, lacking the internal state of suffering present in humans.

This "animal-machine" theory, or animal-automaton theory, became prominent in Europe and North America and had significant implications for the treatment of animals. It effectively sanctioned the maltreatment of animals by removing any moral obligation to consider their welfare, as they were perceived as unfeeling machines. This perspective was embedded in legal and societal norms until the mid-19th century. For example, Descartes is reported to have performed vivisections on conscious animals, such as dogs, and would tell observers not to worry, claiming the animals' cries were merely mechanical responses.

The Cartesian view of animals began to erode with the publications of Charles Darwin in the 19th century. Darwin's theory of evolution emphasized the continuity between humans and other species, suggesting the possibility of animal suffering and challenging the notion of a fundamental, qualitative difference between human and animal minds.

2.7. Religion and Theology

René Descartes considered himself a devout Roman Catholic throughout his life, and one of the stated purposes of his *Meditations on First Philosophy* was to defend the Catholic faith through rational argument. He presented proofs for the existence of a benevolent God in the Third and Fifth Meditations, arguing that God's non-deceiving nature guarantees the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions, thereby establishing the possibility of certain knowledge about the external world.

Despite his personal conviction and efforts to reconcile his philosophy with theology, Descartes's ideas encountered intense opposition from both Protestant and Catholic authorities during his time. Critics, such as Blaise Pascal, accused him of deism, famously remarking, "I cannot forgive Descartes; in all his philosophy, Descartes did his best to dispense with God. But Descartes could not avoid prodding God to set the world in motion with a snap of his lordly fingers; after that, he had no more use for God." Pascal viewed Descartes's God as a mere mechanical first cause, rather than the personal, actively intervening God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Conversely, a powerful contemporary, Martin Schoock, accused Descartes of atheism, despite Descartes providing an explicit critique of atheism in his *Meditations*.

The Catholic Church officially prohibited Descartes's books in 1663, placing them on the *Index Librorum Prohibitorum*. This condemnation reflected the Church's concern that his emphasis on individual reason and his mechanistic explanations of the natural world could undermine traditional religious authority and dogma.

Descartes generally steered clear of direct theological questions that depended on God's free will, focusing instead on demonstrating that his metaphysics was not incompatible with theological orthodoxy. When challenged about not having established the immortality of the soul merely by distinguishing mind and body, he replied that he did not presume to use human reason to settle matters dependent on God's free will.

Regarding skepticism about the external world, Descartes argued that sensory perceptions come to him involuntarily, indicating an external cause. He posited that God, being perfectly good and non-deceiving, would not implant in him a "propensity" to believe in material things if they did not exist. For Descartes, God is the ultimate "substance" that requires no assistance to exist or function, while minds are substances that require only God for their operation. His theories on the soul's scientific investigation were also seen as dangerous by religious authorities, as he challenged the view of the soul as purely divine.

3. Mathematical Contributions

Descartes's contributions to mathematics were revolutionary, fundamentally altering the field and providing essential groundwork for future developments, particularly in the unification of algebra and geometry.

3.1. Analytic Geometry and Cartesian Coordinates

One of René Descartes's most significant and enduring legacies is his invention of analytic geometry, which unified the previously separate fields of algebra and geometry. This groundbreaking work is detailed in his 1637 essay, *La Géométrie*, appended to his *Discourse on the Method*.

Descartes was the first to systematically apply algebraic methods to geometric problems. He introduced the concept of representing points in a plane using pairs of numbers, which are now known as Cartesian coordinates (named in his honor). This system allows geometric shapes and figures to be described by algebraic equations. For example, a curve can be defined by an equation relating the *x* and *y* coordinates of its points. This innovation transformed geometry from a study of figures and constructions into a study of equations, making it possible to solve geometric problems using algebraic manipulations.

Before Descartes, European mathematicians viewed geometry as more fundamental, often providing geometric proofs for algebraic rules. Descartes, however, assigned a foundational place to algebra, using it as a method to automate or mechanize reasoning, especially concerning abstract and unknown quantities. He challenged the traditional view that abstract quantities like *a*2 could only represent an area, arguing that it could also represent a length, thereby freeing algebra from strict geometric interpretations. Although he did not fully develop the concept, Descartes also envisioned a more general science of algebra or "universal mathematics," which foreshadowed symbolic logic and the mechanization of general reasoning, a concept later explored by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

3.2. Notation and Rules

Descartes introduced several important innovations in mathematical notation that are still in use today. He standardized the convention of using the last letters of the alphabet (x, y, and z) to represent unknown quantities in equations, and the first letters (a, b, and c) to represent known quantities or constants.

Furthermore, he pioneered the use of superscripts to denote powers or exponents, writing, for example, x2 for x squared, a3 for a cubed, and so on, extending this notation indefinitely. This replaced earlier, more cumbersome ways of writing powers (e.g., xx for x2).

In addition to these notational advancements, Descartes formulated the Descartes' rule of signs, a method used to determine the number of positive and negative real roots of a polynomial equation. This rule states that the number of positive roots of a polynomial is either equal to the number of sign changes between consecutive non-zero coefficients, or less than it by an even number. Similarly, the number of negative roots can be determined by applying the same rule to the polynomial with *x* replaced by -*x*.

These innovations in notation and rules significantly simplified algebraic expressions and calculations, making mathematics more accessible and paving the way for more complex developments.

3.3. Foundations for Calculus

René Descartes's work in analytic geometry provided crucial foundations for the later development of calculus by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. His method of representing curves and geometric problems using algebraic equations allowed for a new approach to understanding rates of change and areas.

Specifically, Descartes's ability to express curves algebraically enabled mathematicians to conceptualize and solve problems related to tangent lines to curves. Finding the tangent to a curve at a given point is a fundamental problem in differential calculus. While Descartes himself did not develop calculus, his algebraic methods for describing curves laid the groundwork for Newton and Leibniz, who, building on these concepts, developed the infinitesimal calculus to precisely address such problems.

His systematic approach to linking algebra and geometry, as presented in *La Géométrie*, provided the necessary tools and conceptual framework that allowed Newton and Leibniz to formulate the fundamental theorems of calculus, which revolutionized mathematics and physics. Newton, in particular, was significantly influenced by Descartes's work, especially through Frans van Schooten's expanded Latin edition of *La Géométrie*, and continued Descartes's work on cubic equations, further freeing the subject from Greek geometric constraints.

4. Scientific Contributions

Descartes's scientific contributions were deeply intertwined with his mechanical philosophy, which sought to explain natural phenomena through physical mechanisms, influencing fields such as physics, optics, and meteorology.

4.1. Physics and Mechanical Philosophy

Descartes is often credited as one of the first thinkers to emphasize the use of reason and a systematic approach to develop the natural sciences. For him, philosophy was a unified system of knowledge, which he famously likened to a tree: "Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk, which are reduced to three principals, namely, Medicine, Mechanics, and Ethics." This holistic view underscored his belief that all knowledge, including the sciences, was interconnected and derived from fundamental metaphysical principles.

His interest in physics began in 1618, upon meeting Isaac Beeckman, an amateur scientist and mathematician who was a proponent of mechanical philosophy. Beeckman's corpuscularian approach, which explained physical phenomena in terms of the motion and interaction of tiny particles, deeply influenced Descartes. This collaboration led Descartes to formulate many of his theories based on mechanical and geometric physics. They worked together on problems of free fall, catenaries, conic sections, and fluid statics, convinced that mathematics and physics needed to be thoroughly linked. Beeckman also introduced him to many of Galileo's ideas.

Descartes's **mechanical philosophy** posited that the universe operates like a vast machine, composed solely of matter in motion, governed by fixed, divinely ordained laws. He rejected the Aristotelian notion of "final causes" or inherent purposes in nature, explaining all natural phenomena through the size, shape, and motion of particles. This objective, mechanistic worldview contrasted sharply with the animistic or vitalistic views of the Renaissance.

In his *Principles of Philosophy* (1644), Descartes outlined his views on the universe, including his three **laws of motion**, which would later serve as a model for Newton's own laws of motion. He defined "quantity of motion" (quantitas motusLatin) as the product of the size (or mass, though he didn't distinguish it from weight or size) and speed of a body, and crucially, he claimed that the total quantity of motion in the universe is conserved. He stated, "[God] created matter, along with its motion... merely by letting things run their course, he preserves the same amount of motion... as he put there in the beginning." This was an early form of the law of conservation of momentum, though it differed from the modern concept by focusing on speed rather than velocity and not having a clear distinction between mass and weight.

Descartes also proposed the **vortex theory** of planetary motion, suggesting that the universe was filled with a subtle fluid that swirled in vortices, carrying planets around the sun and moons around planets. This theory, though later rejected by Newton in favor of his law of universal gravitation (much of Newton's *Principia* is devoted to refuting it), was a significant attempt to provide a purely mechanical explanation for celestial movements.

While Descartes's physics contained many errors and lacked rigorous mathematical formulation and experimental verification compared to Galileo's or Newton's, his insistence on a mechanistic, mathematical explanation of nature was a crucial step in the Scientific Revolution, laying the conceptual groundwork for modern physics. He also anticipated the concept of work (in physics), writing in 1637 that "Lifting 100 lb (100 lb) 1 ft twice over is the same as lifting 200 lb (200 lb) 1 ft, or 100 lb (100 lb) 2 ft," illustrating the equivalence of different combinations of force and distance in achieving a result.

4.2. Optics and Meteorology

Descartes made significant contributions to the field of optics. In his essay "La Dioptrique" (Dioptrics), published as part of *Discourse on the Method* in 1637, he presented his work on light and vision. He independently discovered the law of reflection, and his essay was the first published mention of this law. More notably, he is credited with discovering the law of refraction, often known as Snell's law (or Descartes's law in France). Using geometric construction and this law, he provided a detailed explanation for the formation of a rainbow, correctly calculating its angular radius to be 42 degrees. His work in optics also included discussions on the anatomy of the eye, the process of vision, and the design of lenses for telescopes and microscopes, emphasizing their utility.

Descartes also delved into meteorology, presenting his theories in "Les Météores" (The Meteors), another appendix to his *Discourse on the Method*. He proposed a particle theory of elements, suggesting that elements were made of small particles that imperfectly joined, leaving small spaces filled with faster, "subtile matter." He believed that particles of water were like "little eels" that could easily separate, while more solid materials were composed of irregularly shaped particles. The size and shape of these particles, along with their interactions, determined various secondary qualities of materials, such as temperature.

While rejecting most of Aristotle's meteorological theories, Descartes retained some terminology like "vapors" and "exhalations." He theorized that these "vapors" were drawn into the sky by the sun from "terrestrial substances" and, along with falling clouds displacing air, generated wind. He also offered explanations for thunder and lightning. He posited that thunder occurred when a top cloud, condensing from hot air, released particles that collided with a bottom cloud. He compared this to avalanches, where heated, heavier snow falling onto snow below creates a booming sound. For lightning, he believed it was caused by "fine and inflammable" exhalations trapped between colliding clouds, igniting upon impact, especially in hot and dry weather.

Regarding precipitation, Descartes theorized that clouds were made of water and ice drops, and rain fell when the air could no longer support them. If the air was not warm enough to melt the raindrops, it would fall as snow. Hail was explained as cloud drops melting and then refreezing due to cold air. It is notable that Descartes's meteorological theories, unlike his work in optics, did not rely on mathematics or instruments (which were largely unavailable at the time) but instead used qualitative reasoning to deduce his hypotheses.

5. Historical Impact and Reception

René Descartes's profound and lasting influence on Western thought is undeniable, marking a pivotal shift in philosophy and science, though his ideas were also met with significant controversy. His five key influential ideas were: (a) his mechanistic view of the universe; (b) his positive attitude towards scientific investigation; (c) his emphasis on the use of mathematics in science; (d) his defense of the initial skeptical stance; and (e) his focus on epistemology.

5.1. Emancipation from Traditional Authority

Descartes is widely recognized as the "father of modern Western philosophy," whose revolutionary approach fundamentally altered its trajectory and established the groundwork for modernity. His first two *Meditations on First Philosophy*, which introduce and apply his famous methodic doubt, are considered the most influential parts of his writings on modern thought.

His philosophical innovation lay in shifting the authoritative guarantor of truth from external sources, such as God or Church doctrine, to the individual human being. By asking "of what can I be certain?" rather than "what is true?", Descartes redirected the quest for knowledge inward, making certainty reliant on individual judgment and clear and distinct perception. This marked an "anthropocentric revolution," elevating the human being to the status of a subject, an agent, and an emancipated being endowed with autonomous reason. This was a revolutionary step that laid the foundation for modernity, whose repercussions are still felt today. It signified the emancipation of humanity from Christian revelational truth and Church doctrine, allowing humanity to establish its own laws and take its own stand based on reason. In this modern paradigm, the guarantor of truth is no longer God but human beings, each becoming a "self-conscious shaper and guarantor" of their own reality. This transformation from a child obedient to God to a reasoning adult, a subject and agent, characterized the shift from the Christian medieval period to the modern era, a shift that Descartes notably articulated in philosophy.

According to Martin Heidegger, Descartes's perspective, by interpreting man as *subiectum*, also established the metaphysical presupposition for all subsequent anthropology. Thus, Descartes's philosophical revolution is often seen as having sparked modern anthropocentrism and subjectivism.

5.2. Influence on Modern Thought

Descartes's influence on modern thought extends far beyond philosophy, permeating science and the broader intellectual landscape. His *Meditations on First Philosophy* remains a standard text in most university philosophy departments, serving as a foundational work for studying epistemology and metaphysics.

He played a crucial role in shaping rationalism, a philosophical tradition that emphasizes reason as the primary source of knowledge, influencing subsequent thinkers like Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. His work also deeply impacted the concept of the modern subject, highlighting the individual's self-awareness and capacity for autonomous thought.

The enduring relevance of Descartes's ideas is evident in ongoing debates. As noted by Anthony Gottlieb, Descartes and Thomas Hobbes continue to be discussed in the 21st century because their philosophies still offer pertinent insights into fundamental questions, such as the implications of scientific advancement for human self-understanding and religious beliefs, and how governments should navigate religious diversity.

Philosophers continue to engage with Descartes's thought experiments. Agnes Callard, for instance, describes his method of complete, systematic doubting in the *Meditations* as an exercise to "see what you come to." She suggests that Descartes ultimately arrives at a "real truth that he can build upon inside of his own mind," drawing parallels to Hamlet's introspective monologues. The contemporary argument of living in a simulation, where an "evil demon" is replaced by a simulation, can also be traced back to Descartes's skepticism, which he famously refuted by ultimately grounding reality in the "mind of God."

5.3. Reception and Controversy

The reception of Descartes's works during and after his lifetime was mixed. Commercially, the *Discourse on the Method* initially appeared in a limited edition of 500 copies, with 200 reserved for the author, and did not sell out during his lifetime. Similarly, the only French edition of the *Meditations on First Philosophy* did not sell out by the time of his death. However, a Latin edition of the *Meditations* was eagerly sought by Europe's scholarly community and proved to be a commercial success for Descartes.

Despite his growing fame in academic circles towards the end of his life, the teaching of his works in universities was controversial. For instance, Henri de Roy, a Professor of Medicine at the Utrecht University, was condemned by the university's Rector, Gijsbert Voet, for teaching Descartes's physics. This highlights the tension between Descartes's innovative ideas and the entrenched scholastic traditions.

The Catholic Church officially condemned Descartes's books in 1663, placing them on the *Index Librorum Prohibitorum*. In 1671, Louis XIV of France prohibited all lectures in Cartesianism. This condemnation reflected the Church's concern that his emphasis on individual reason and his mechanistic explanations of the natural world could undermine traditional religious authority and dogma.

Nevertheless, Descartes's *Meditations on First Philosophy* is widely considered "one of the key texts of Western philosophy" and the "most widely studied of all Descartes' writings," according to philosophy professor John Cottingham. His ideas sparked significant philosophical debates, particularly with the empiricists, and continue to be interpreted and reinterpreted by scholars across various disciplines.

5.4. Purported Rosicrucianism

The question of René Descartes's involvement with or influence from the Rosicrucian movement has been a subject of historical debate.

Several points fuel this speculation:

- His Latin name, Renatus Cartesius, shares the initials "R.C.," which were widely used as an acronym by Rosicrucians.

- In 1619, Descartes moved to Ulm, a city in Germany that was a renowned international center for the Rosicrucian movement at the time.

- During his travels in Germany, he reportedly met Johannes Faulhaber, a mathematician who had previously expressed a personal commitment to joining the Rosicrucian brotherhood.

Further, Descartes dedicated an unfinished work titled *The Mathematical Treasure Trove of Polybius, Citizen of the World* to "learned men throughout the world and especially to the distinguished B.R.C. (Brothers of the Rosy Cross) in Germany." While the publication of this work remains uncertain, this dedication is often cited as a strong indicator of his potential connection or at least his acknowledgment of the Rosicrucian community. These various connections have led to ongoing discussions among scholars regarding the extent of Rosicrucian influence on Descartes's early intellectual development and his philosophical pursuits.

6. Bibliography

René Descartes's major works span philosophy, mathematics, and science, reflecting his comprehensive intellectual project. His writings were often published in Latin for scholarly audiences and later translated into French, sometimes under his supervision.

6.1. Major Works

- 1618. *Compendium Musicae***: A treatise on music theory and aesthetics, dedicated to Isaac Beeckman. It was published posthumously in 1650.

- 1626-1628. *Regulae ad directionem ingenii***: An incomplete work on his method, first published posthumously in Dutch translation in 1684 and in the original Latin in 1701.

- c. 1630. *De solidorum elementis***: Concerns the classification of Platonic solids and three-dimensional figurate numbers, possibly prefiguring Euler's polyhedral formula. It was unpublished in his lifetime and rediscovered much later.

- 1630-1631. *La recherche de la vérité par la lumière naturelle***: An unfinished dialogue, published posthumously in 1701.

- 1630-1633. *Le Monde* (The World) and *L'Homme* (Man)**: Descartes's first systematic presentation of his natural philosophy, explaining the universe through mechanical principles. *Man* was published posthumously in Latin translation in 1662, and *The World* in 1664, after he withheld its publication due to Galileo's condemnation.

- 1637. *Discours de la méthode***: A foundational text outlining his method of doubt and the *Cogito*. It served as an introduction to three essays: *La Dioptrique* (Dioptrics), *Les Météores* (The Meteors), and *La Géométrie* (Geometry).

- 1637. *La Géométrie* (Geometry)**: Descartes's major work in mathematics, where he introduced analytic geometry and the Cartesian coordinate system.

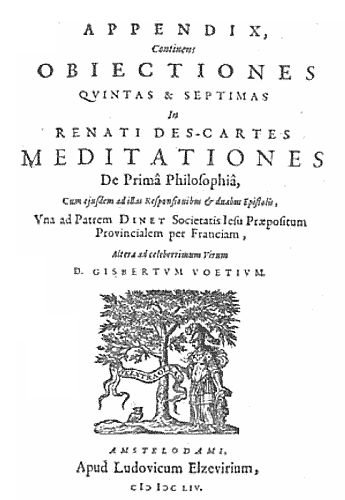

- 1641. *Meditationes de prima philosophia***: Also known as *Metaphysical Meditations*, this Latin treatise presents his proofs for the existence of God, the distinction between mind and body, and the nature of knowledge. A second edition in 1642 included additional objections and replies.

- 1644. *Principia philosophiae***: A comprehensive Latin textbook intended to replace Aristotelian philosophy in universities, synthesizing ideas from his *Discourse* and *Meditations*. A French translation, *Principes de philosophie*, supervised by Descartes, appeared in 1647.

- 1647. *Notae in programma* (Comments on a Certain Broadsheet)**: A reply to his former disciple, Henricus Regius.

- 1648. *La description du corps humain***: Published posthumously in 1667.

- 1648. *Responsiones Renati Des Cartes...* (Conversation with Burman)**: Notes from a Q&A session between Descartes and Frans Burman on April 16, 1648, rediscovered and published in 1896.

- 1649. *Les passions de l'âme***: Dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate, this work analyzes human emotions and their physiological basis.

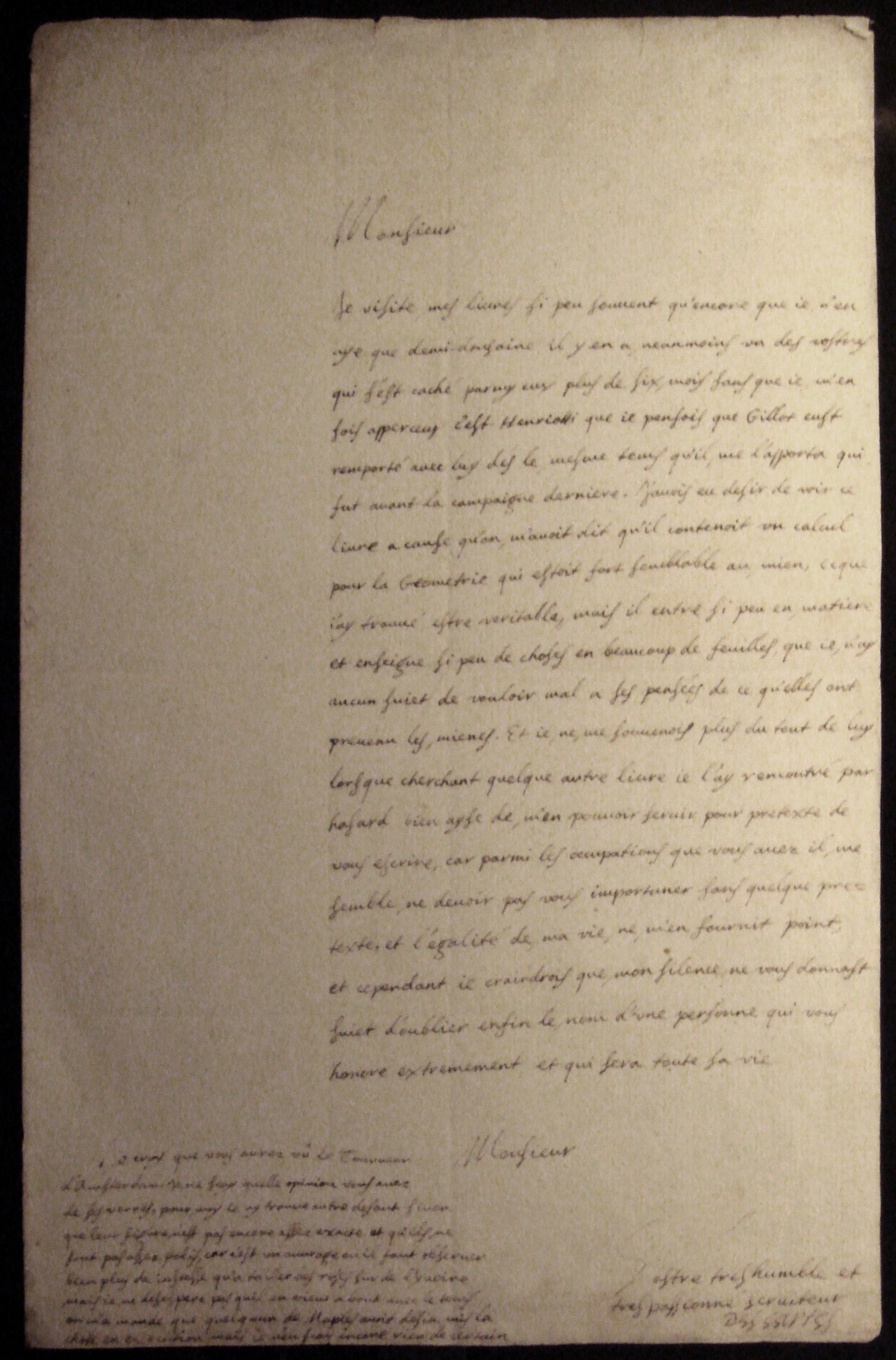

- 1657. *Correspondance***: A collection of his letters, published in three volumes (1657, 1659, 1667) by his literary executor Claude Clerselier.

6.2. Collected Editions and Translations

The study of Descartes's works has been greatly facilitated by several comprehensive collected editions and translations. The most authoritative critical edition of his complete works is *Oeuvres de Descartes*, edited by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery, published in Paris between 1897 and 1913 in 13 volumes, and later revised. This edition is traditionally cited as "AT" followed by a Roman numeral for the volume.

For English readers, the most widely used collection is *The Philosophical Writings of Descartes*, a three-volume set translated by J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, A. Kenny, and D. Murdoch, published by Cambridge University Press starting in 1988. This collection is typically cited as "CSM" (or "CSMK" when Kenny is included) with a Roman numeral for the volume. Another significant English translation is *The Philosophical Works* by E.S. Haldane and G.R.T. Ross, published in 1955 by Dover Publications, cited as "HR."

Beyond these, *René Descartes: The World and Other Writings*, translated and edited by Stephen Gaukroger (1998), is notable for including scientific writings on physics, biology, astronomy, and optics that are often abridged in other philosophical collections. More recent comprehensive editions include *Œuvres complètes*, a new edition by Jean-Marie Beyssade and Denis Kambouchner (Paris: Gallimard), and extensive Italian collected editions published by Bompiani, such as *René Descartes. Opere 1637-1649* and *René Descartes. Tutte le lettere 1619-1650*.

These collected editions and translations are indispensable for scholarship, providing access to Descartes's vast and influential body of work across various disciplines.