1. Life

Thomas Hobbes's life spanned a period of significant political and intellectual upheaval in England, from his birth amidst the threat of the Spanish Armada to his later years under the restored monarchy. His experiences and interactions with prominent figures and intellectual circles profoundly shaped his philosophical development.

1.1. Early Life and Family

Thomas Hobbes was born prematurely on April 5, 1588, in Westport, which is now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England. His mother reportedly went into labor upon hearing news of the approaching Spanish Armada, leading Hobbes to famously quip, "my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear." He had an older brother, Edmund, and a sister, Anne; his mother's name is not known.

His father, Thomas Sr., served as the vicar of both Charlton and Westport. According to Hobbes's biographer, John Aubrey, Thomas Sr. was uneducated and "disesteemed learning." A fight with local clergy outside his church forced Thomas Sr. to leave London, abandoning his family. Consequently, Hobbes and his siblings were placed under the care of his wealthy uncle, Francis Hobbes, a glove manufacturer who had no children of his own. Francis provided the financial support that enabled Hobbes to pursue his education.

1.2. Education

Hobbes began his education at Westport church at the age of four. He then attended the Malmesbury school before enrolling in a private school run by Robert Latimer, an Oxford graduate. Hobbes proved to be a diligent and capable student, known for his excellent aptitude in languages. Between 1601 and 1602, he entered Magdalen Hall, the precursor to Hertford College, Oxford, where he was taught scholastic logic and mathematics. The principal, John Wilkinson, a Puritan, had some influence on Hobbes. Before attending Oxford, Hobbes had already translated Euripides' Medea from Greek into Latin verse.

At university, Hobbes showed little interest in the traditional scholastic curriculum, preferring to follow his own course of study. He completed his B.A. degree by incorporation at St John's College, Cambridge, in 1608. Following his graduation, Sir James Hussey, his master at Magdalen, recommended Hobbes as a tutor to William Cavendish, the son of William Cavendish, the 1st Earl of Devonshire. This marked the beginning of Hobbes's lifelong and significant association with the influential Cavendish family.

1.3. Early Career and Travels

Hobbes became a companion, secretary, friend, and treasurer to the younger William Cavendish, and together they embarked on a Grand Tour of Europe between 1610 and 1615. During this period, William Cavendish also served as a Member of Parliament in 1614 and 1621, exposing Hobbes to the practicalities of politics. This journey exposed Hobbes to European scientific and critical methods, which stood in stark contrast to the scholastic philosophy he had encountered at Oxford. During this tour, in Venice, Hobbes made the acquaintance of Fulgenzio Micanzio, an associate of Paolo Sarpi, a Venetian scholar and statesman known for his writings against the papacy's claims to temporal power.

Hobbes's scholarly efforts during this period were primarily focused on a careful study of classical Greek and Latin authors. The culmination of these studies was his 1628 edition of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, which was the first English translation of the work directly from a Greek manuscript. Hobbes held a deep admiration for Thucydides, praising him as "the most politic historiographer that ever writ." In his autobiography, Hobbes reportedly stated that Thucydides' work demonstrated "how incompetent democracy is," a sentiment that confirmed or crystallized many aspects of Hobbes's own political thought, including his pro-monarchy stance and his skepticism towards democracy. This work also notably included maps of ancient Greece, which Hobbes himself had compiled and drawn from various sources. Additionally, three discourses published in 1620, known as Horae Subsecivae: Observations and Discourses, are believed to be early works by Hobbes from this period.

Although Hobbes associated with literary figures such as Ben Jonson and briefly served as Francis Bacon's amanuensis, translating some of Bacon's Essays into Latin, he did not fully dedicate himself to philosophy until after 1629. In June 1628, his employer, William Cavendish, the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague, and his widow, Countess Christian, subsequently dismissed Hobbes.

Soon after, in 1629, Hobbes found new employment as a tutor to Gervase Clifton, the son of Sir Gervase Clifton, 1st Baronet. He remained in this role until November 1630, spending most of this time in Paris. During this period, from 1629 to 1630, Hobbes also traveled to France and Switzerland with his pupil. In Geneva, between April and June 1630, he began reading Euclid's Elements and became deeply impressed by Euclid's deductive method, which he later adopted as a primary method for his own academic pursuits.

By 1631, Hobbes had returned to England and resumed his work with the Cavendish family, this time tutoring William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, the eldest son of his former pupil. During these next seven years, alongside his tutoring duties, Hobbes significantly expanded his own philosophical knowledge, developing a keen interest in key philosophical debates. This period, the 1630s, was crucial for Hobbes's intellectual development, marking the growth of his interest in science, particularly optics, and the emergence of his political philosophy, as evidenced by his work Elements of Law. In 1634, he again traveled to Continental Europe, visiting France and Italy with his student, where he became acquainted with French scientists and mathematicians and studied the principles of natural science.

Upon his return to England in October 1636, Hobbes dedicated more time to philosophical works, as his pupil had matured, granting him more leisure. One of his earliest scientific-philosophical works was a manuscript on optics titled Latin Optical MS, completed by 1640. He also wrote other manuscripts on metaphysics and epistemology. Hobbes's work in science and metaphysics was interrupted in the late 1630s by the escalating political tensions in England. In 1637, the absolute power of King Charles I faced increasing challenges. Hobbes openly supported the king, dedicating his book Elements of Law to addressing the issue of absolute power.

1.4. Exile in Paris and Intellectual Activities

In 1640, anticipating political unrest in England, Hobbes decided to move to Paris, France, for his safety and intellectual stimulation. His departure was directly prompted by a parliamentary debate on November 7, 1640, where anti-monarchists began openly opposing those who supported absolute rule. Fearing repercussions for his work Elements of Law, Hobbes fled to Paris, where he would remain for 11 years.

In Paris, Hobbes quickly integrated into the intellectual scene, aided by his colleague Marin Mersenne. In 1642, Mersenne facilitated the publication of Hobbes's work De Cive. This book established Hobbes as a political writer of considerable reputation across Europe. Mersenne also helped publish some of Hobbes's works in physics and optics in two compilation volumes in 1644, titled Cogitata physico-mathematica and Universae. Through Mersenne, Hobbes also became acquainted with other French philosophers and scientists in the early 1640s.

During the 1640s, Hobbes largely focused on physics, metaphysics, and theology, rather than political philosophy. Between 1642 and 1643, he wrote a work challenging the views of the Catholic Aristotelian philosopher Thomas White. In 1645, he engaged in a prolonged polemic with John Bramhall, an Anglican theologian, concerning the nature of free will.

In 1646, Hobbes was appointed as a mathematical instructor to the young Charles, Prince of Wales, who had arrived in Paris from Jersey around July. This engagement lasted until 1648, when Charles moved to Holland. This role brought Hobbes into closer contact with exiled royalist politicians, court officials, and ecclesiastical figures, drawing him back into political discourse.

The English Civil War began in 1642, and as the royalist cause weakened in mid-1644, many royalists sought refuge in Paris, where Hobbes became acquainted with them. This renewed his political interests, leading to the republication and wider distribution of De Cive. The printing, managed by Samuel de Sorbiere through the Elsevier press in Amsterdam, began in 1646 and included a new preface and notes in response to objections.

The company of the exiled royalists spurred Hobbes to produce Leviathan, which articulated his theory of civil government in response to the political crisis of the war. In this work, Hobbes famously compared the State to a monster (leviathan) composed of men, arguing that it is created out of human needs and can be dissolved by civil strife stemming from human passions. The book concluded with a "Review and Conclusion" that addressed the critical question of whether a subject had the right to change allegiance if a former sovereign's power to protect was irrevocably lost.

During the years he spent composing Leviathan, Hobbes remained in or near Paris. In 1647, he suffered a severe illness that incapacitated him for six months. Upon recovery, he resumed his writing and completed Leviathan by 1650. Meanwhile, a translation of De Cive was underway, though scholars debate whether Hobbes himself was the translator.

In 1650, a pirated edition of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic was published. It was divided into two smaller volumes: Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie; and De corpore politico, or the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick. The following year, in 1651, the translation of De Cive appeared under the title Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society. The printing of his magnum opus, Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil, was also completed and appeared in mid-1651. Its iconic title-page engraving depicted a crowned giant, composed of tiny human figures, towering over a landscape, holding a sword and a crozier. The work had an immediate and profound impact, making Hobbes both widely lauded and fiercely criticized.

The publication of Leviathan severed Hobbes's ties with the exiled royalists, who, angered by its secularist spirit, might have sought to harm him. The book's views also greatly displeased both Anglicans and French Catholics. While its initial readers were surprised by its religious content, widespread denunciation did not immediately follow. Hobbes had begun planning his return to England in 1648, a decision influenced by the changing political landscape, including the execution of King Charles I in 1649, and the departure of close intellectual companions like Marin Mersenne (who had died) and Pierre Gassendi (who moved to southern France). Seeking protection, Hobbes appealed to the revolutionary English government and returned to London in the winter of 1651. After submitting to the Council of State, he was allowed to live a private life in Fetter Lane.

1.5. Later Life and Patronage

In 1658, Hobbes published De Homine, the final section of his philosophical system, completing a scheme he had conceived more than 19 years earlier. This treatise primarily consisted of an elaborate theory of vision, with the remainder addressing topics more fully explored in Human Nature and Leviathan. In addition to controversial mathematical writings, including those on geometry, Hobbes continued to produce philosophical works.

With the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Hobbes gained new prominence. "Hobbism" became a byword for ideas that respectable society ought to denounce. However, the young king, Charles II, Hobbes's former pupil, remembered him and summoned him to court, granting him a pension of 100 GBP.

The king's protection proved crucial when, in 1666, the House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism and profaneness. On October 17, 1666, the committee handling the bill was "empowered to receive information touching such books as tend to atheism, blasphemy and profaneness... in particular... the book of Mr. Hobbes called the Leviathan." Terrified by the prospect of being labeled a heretic, Hobbes burned some of his compromising papers and began to investigate the legal status of heresy. The results of his inquiry were presented in three short Dialogues, appended to his Latin translation of Leviathan, published in Amsterdam in 1668. In this appendix, Hobbes argued that since the High Court of Commission had been abolished, there was no longer a court of heresy to which he was answerable, and that nothing could be considered heresy except opposing the Nicene Creed, which he maintained Leviathan did not do.

The primary consequence of this bill was that Hobbes could no longer publish anything in England on subjects related to human conduct. The 1668 edition of his works had to be printed in Amsterdam because he could not obtain a censor's license in England. Other writings, including Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640 to the year 1662, were not made public until after his death. For a period, Hobbes was even forbidden from responding to attacks from his critics. Despite these challenges, his reputation abroad remained formidable, particularly in France, where he was regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of his time and Leviathan gained considerable fame.

Hobbes spent the last four or five years of his life with his patron, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire, at the family's Chatsworth House estate. He had been a close friend of the Cavendish family since 1608, when he first tutored an earlier William Cavendish. Many of Hobbes's manuscripts were found at Chatsworth House after his death. His final works included an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672, and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into "rugged" English rhymes in 1673, which led to a complete translation of both the Iliad and Odyssey in 1675. He remained remarkably productive into his old age, continuing to write until his death at 91.

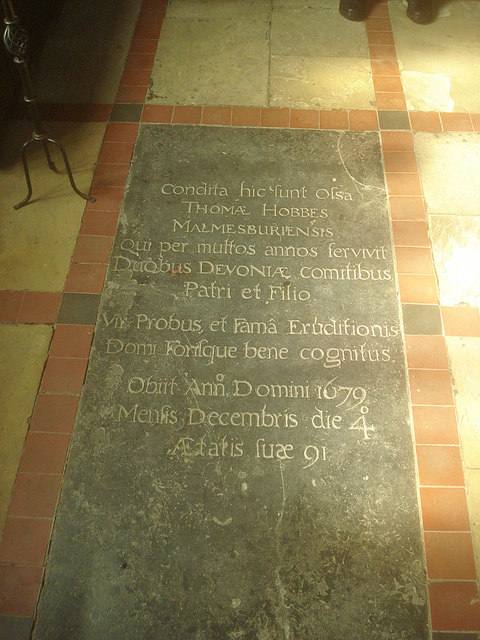

1.6. Death

In October 1679, Hobbes suffered from a bladder disorder, followed by a paralytic stroke. He died on December 4, 1679, at the age of 91, at Hardwick Hall, another estate owned by the Cavendish family. His last words were reportedly, "A great leap in the dark," uttered in his final conscious moments. His body was interred in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire. An epitaph, said to have been written by Hobbes himself, reads: "He was an expert, and because of his reputation in many sciences, he was widely known both domestically and abroad." His long life notably spanned the reigns of twelve different kings of the Ayutthaya Kingdom in Thailand.

2. Major Works

Thomas Hobbes's intellectual output was extensive and diverse, encompassing not only political philosophy but also history, mathematics, and natural science. His most renowned work, Leviathan, stands as a cornerstone of modern political thought, while his other writings further elaborate on his comprehensive philosophical system.

2.1. Leviathan

Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil, published in mid-1651, is Thomas Hobbes's most influential work and a seminal text in Western political philosophy. In this treatise, Hobbes systematically laid out his doctrine for the foundation of states and legitimate governments, aiming to establish an objective science of morality. A significant portion of the book is dedicated to demonstrating the absolute necessity of a strong central authority to prevent the evils of discord and civil war, a conviction heavily influenced by the recent English Civil War.

The work famously compares the State to a monstrous entity, the leviathan, which is composed of individual human beings. Hobbes argued that this "artificial man" is created under the immense pressure of human needs and can be dissolved by civil strife stemming from uncontrolled human passions. The book concludes with a "Review and Conclusion" that directly addresses the political crisis of the war, tackling the crucial question of whether a subject retains the right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to provide protection is irrevocably lost.

Upon its publication, Leviathan had an immediate and profound impact, making Hobbes both widely celebrated and fiercely denounced. Its secularist spirit particularly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics, leading to significant controversy and even threats against Hobbes's life, prompting his return to England. The book's iconic title-page engraving, depicting a crowned giant composed of tiny human figures, towering over a landscape and holding a sword and a crozier, became instantly recognizable. While Hobbes's work was seen by some as a shift towards a more neutral political stance, focusing on the nature of power itself rather than explicitly endorsing monarchy, its views on religion also caused considerable friction with the clergy around Charles II, leading to accusations of heresy.

2.2. Other Major Works

Hobbes's philosophical system was ambitious, aiming to explain the entirety of reality through a mechanistic lens, from the physical world to human nature and the state. This grand scheme was articulated across several key works:

- Early Works and Translations: His earliest known work was a Latin translation of Euripides' Medea (1602), though it is now lost. He also contributed three discourses-"A Discourse of Tacitus," "A Discourse of Rome," and "A Discourse of Laws"-to The Horae Subsecivae: Observation and Discourses (1620). His 1629 translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War was a significant scholarly achievement. Other early writings include the poem De Mirabilis Pecci, Being the Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire (1626, published 1636), and the disputed A Short Tract on First Principles (1630). He also wrote A Briefe of the Art of Rhetorique (1637), also known as The Whole Art of Rhetoric.

- The Elements of Philosophy Trilogy: Hobbes planned a comprehensive philosophical system in three parts:

- De Corpore (Concerning Body, 1655, Latin; English translation 1656): This first part laid out his foundational ideas on physics, mathematics, and logic, arguing that all reality is reducible to matter in motion. It controversially included his erroneous proof of squaring the circle.

- De Homine (Concerning Man, 1658, Latin): The second part focused on human nature, sensation, and the passions, largely presenting an elaborate theory of vision and discussing topics from his earlier Human Nature.

- De Cive (Concerning the Citizen, 1642, Latin; English translation Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society 1651): This was the third part of his planned trilogy, though published first due to the political climate. It detailed his political philosophy, arguing for the necessity of a strong sovereign to prevent civil war.

- Political and Historical Works:

- Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (1640): Initially circulated as a manuscript, this work was a precursor to De Cive and Leviathan, outlining his early political thought. A pirated edition was published in 1650, divided into Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie and De corpore politico, or the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick.

- Behemoth, or The Long Parliament (written 1668, published posthumously 1681): This historical account of the English Civil War provided Hobbes's analysis of the causes and events leading to the conflict, offering a historical complement to his theoretical work in Leviathan. It was initially suppressed by the King.

- Other Philosophical and Scientific Writings: Hobbes engaged in numerous intellectual debates through his writings. These include his Objectiones ad Cartesii Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (1641), written at the request of René Descartes himself. Hobbes's critique, known as the "Third Objections," was met with a cold response from Descartes, who perceived a lack of understanding of his philosophy. Hobbes also conducted a critical analysis of Thomas White's work in De Motu, Loco et Tempore (1643), and various optical treatises like Tractatus Opticus II (1639) and A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques (1646). He also published works on the free will debate, such as Of Liberty and Necessity (1646, published 1654) and The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance (1656). His later works include Decameron Physiologicum: Or, Ten Dialogues of Natural Philosophy (1678) and his Latin autobiography Thomae Hobbessii Malmesburiensis Vita. Authore seipso (1679).

- Classical Translations: In his later years, Hobbes undertook translations of Homer's epics, completing English versions of both the Iliad and the Odyssey in 1673 and 1675, respectively.

3. Political Philosophy

Thomas Hobbes's political philosophy is characterized by its systematic approach, drawing heavily from his mechanistic worldview to explain the origins and necessity of political authority. His theories on the state of nature, the social contract, and absolute sovereignty remain central to the study of modern political thought.

3.1. State of Nature and Natural Law

Hobbes's political theory aimed to be a quasi-geometrical system, where conclusions logically followed from premises, much like in mathematics. His central practical conclusion was that a state or society cannot be secure unless it is under the control of an absolute sovereign. This implied that individuals could not hold property rights against the sovereign, and that the sovereign may therefore take the goods of its subjects without their consent. This view was particularly significant as it developed in the 1630s, a period when Charles I was attempting to raise revenues without parliamentary consent. Hobbes also extended his mechanistic understanding of nature to the social and political realms, making him a progenitor of the concept of 'social structure'.

Hobbes rejected Aristotle's famous thesis that human beings are naturally suited to life in a polis (political community) and only fully realize their nature as citizens. Instead, Hobbes postulated what life would be like without government, a condition he termed the "state of nature." In this state, each person would possess a right, or license, to everything in the world. Hobbes argued that this condition would inevitably lead to a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnesLatin). He famously described this natural state of humankind, devoid of political community, as one where there is "no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

In such a state, people live in constant fear of death and lack the means for comfortable living, as well as the hope of obtaining them. Hobbes believed that human behavior is fundamentally driven by the instinct for self-preservation and the fear of losing one's life. This leads to a constant state of suspicion and hostility, where "man is wolf to man" (homo homini lupus!). He considered the natural right to use violence for self-preservation as a pre-moral affirmation. The strongest human passions are the desire for power, wealth, knowledge, and honor, coupled with an aversion to misery and death. The inherent competition for these desires inevitably leads to conflict. To avoid this perpetual conflict, human reason leads to "natural laws," which are precepts that guide individuals to restrict their natural rights to escape the contradictions inherent in a state where everyone has a right to everything, ultimately threatening their own existence. However, Hobbes contended that these natural laws are not fully enforceable in the state of nature.

3.2. Social Contract Theory

To escape the perilous "war of all against all" in the state of nature, Hobbes argued that people rationally accede to a social contract and establish a civil society. Hobbes is recognized as the first modern political philosopher to articulate this concept with such clarity and detail. According to his theory, society is formed by a population and a sovereign authority, to whom all individuals in that society cede some of their rights for the sake of protection and order. This transfer of individual rights to a sovereign creates a powerful, centralized authority.

The power exercised by this sovereign authority cannot be legitimately resisted, because the sovereign's power derives from the individuals' voluntary surrender of their own sovereign power for protection. Consequently, the individuals are considered the authors of all decisions made by the sovereign. As Hobbes famously stated, "he that complaineth of injury from his sovereign complaineth that whereof he himself is the author, and therefore ought not to accuse any man but himself, no nor himself of injury because to do injury to one's self is impossible."

Crucially, Hobbes viewed the state, or "Leviathan," as an artificial product of this social contract. The contract is made among the citizens themselves, not between the citizens and the state. This means the state is a result of the agreement, not a party to it, and therefore the state has no obligations or responsibilities to its citizens. Individuals surrender all their rights to the state, and once these rights are given to the ruler, they cannot be reclaimed unless the ruler grants them. This condition, Hobbes believed, ensures order, as citizens are deterred from destructive behavior by the fear of punishment, including capital punishment. The loss of individual freedom in relation to the state is presented as the necessary price for living in tranquility, order, and peace.

Hobbes's social contract theory is considered a pioneering argument in the broader field of contractarianism, representing one of the two main moral arguments for the social contract, the other being that put forth by Immanuel Kant. To prevent potential abuse of the state's absolute power, Hobbes suggested two safeguards: first, the sovereign should be aware of the concept of justice, as their actions will ultimately be accountable before God in a final judgment; and second, if the state were to threaten the lives of its citizens, those citizens, driven by their fundamental fear of death, would inevitably rise to destroy the state before it could destroy them, leading to a return to the state of nature, from which a new, potentially better, state might emerge.

3.3. Sovereignty and the Commonwealth

In Hobbes's political philosophy, the concept of sovereignty is paramount and absolute. He argued against any doctrine of separation of powers, contending that any division of authority would inevitably lead to internal strife and jeopardize the stability provided by an absolute sovereign. For Hobbes, the sovereign must control all aspects of society: civil, military, judicial, and even ecclesiastical powers, extending to the very words used by subjects.

The state, symbolized by the powerful Leviathan, must possess absolute power and be feared by all its people to ensure order and happiness. This absolute power is not merely a means to an end but is essential for the state's function. The sovereign's power is orderly and strong when it is concentrated in a single entity, whether that be a monarch, an oligarchy, or even a democracy, provided that the power remains undivided and absolute. Once the people have granted their rights to this sovereign, they cannot retract them or reclaim them unless the sovereign explicitly permits it. This structure, Hobbes believed, compels citizens to obey the laws out of fear of punishment, thereby suppressing their destructive instincts and ensuring social peace.

Hobbes's view was that the sovereign's authority is primarily "state reason," meaning the state embodies the collective rationality necessary to escape the chaos of the state of nature. The state has the right to determine the fate of its people for the sake of maintaining order and peace. The absolute obedience demanded by the state, enforced by punishments including capital punishment, is the necessary condition for citizens to live in security and harmony.

3.3.1. Theory of Power

In Hobbes's framework, power is defined as the existing means to acquire future apparent satisfaction. He categorized power into two types: natural or original power, and instrumental power. Natural or original power stems from an individual's superior physical or mental attributes compared to others. Instrumental power, conversely, is acquired through the exercise of original power and serves as a means to gain even more power. Hobbes considered both natural and instrumental powers as inherent individual capacities.

He further posited that power is a potential for individuals to achieve their desires, and thus it is inherently relative. Power, in his view, can be reduced to a series of qualities and abilities that share little commonality. The supreme form of human power, according to Hobbes, lies in the collective agreement of the majority to confer their power, whether natural or civil, upon a single individual, allowing that person to exercise all power according to their will. This, he asserted, constitutes the power of the people.

4. Philosophical and Scientific Contributions

Beyond his groundbreaking political philosophy, Thomas Hobbes made significant contributions to broader philosophical and scientific discourse, rooted in his commitment to materialism and empiricism.

4.1. Materialism and Empiricism

The core of Hobbes's thought is deeply rooted in empiricism, derived from the Greek word empeiria, meaning 'experienced in' or 'acquainted with'. For Hobbes, experience is the sole origin of all knowledge. He asserted that philosophy is the scientific knowledge of observable effects or facts, arguing that everything in existence is determined by specific causes, operating according to the immutable laws of mathematics and natural science. He believed that only what can be observed by human senses is real, and that this reality exists independently of human reason, directly opposing the tenets of rationalism.

Hobbes was a staunch materialist, contending that all things, including human thoughts, and even concepts like God, heaven, and hell, are ultimately composed of matter in motion. He actively challenged those who believed in immaterial substances. For Hobbes, sensory observation occurs when external objects stimulate human senses, transmitting these impulses to the brain and then to the heart, which in turn produces specific reactions. He viewed human beings mechanistically, as mere heaps of material operating and moving according to the laws of natural science. He dismissed moral-metaphysical assumptions about humans, such as the idea of an inherent social nature, freedom, or the immortality of the soul, considering the soul and reason as merely parts of the body's mechanical processes.

Hobbes was also a pioneer in advocating for the independence of philosophy from religious dogma. He argued that philosophy had been unduly influenced by religious ideas and insisted that its object should be limited to external, moving objects and their characteristics. He maintained that unchanging substances like God, or empirically intangible entities such as spirits and angels, fall outside the domain of philosophy. Instead, philosophy should focus on understanding and controlling nature. He delineated four primary fields within philosophy, all interconnected:

- Geometry: The reflection on objects in space.

- Physics: The reflection on the reciprocal action of objects and their motion.

- Ethics: Which Hobbes viewed as closely related to psychology, involving the reflection on human desires, feelings, and mental motions.

- Politics: The reflection on social institutions.

Through this framework, Hobbes believed that society and human beings could be understood through the principles of motion and matter, much like physical phenomena.

4.2. Religious Views

Thomas Hobbes's religious opinions were highly controversial during his lifetime and remain a subject of scholarly debate, with interpretations ranging from accusations of atheism to claims of orthodox Christianity. In The Elements of Law, Hobbes presented a cosmological argument for the existence of God, positing God as "the first cause of all causes."

Despite this, he was frequently accused of atheism by contemporaries, including John Bramhall, who claimed Hobbes's teachings could lead to atheism. Hobbes vehemently defended himself against such accusations, stating that "atheism, impiety, and the like are words of the greatest defamation possible." Scholars continue to disagree on the precise significance of his unusual religious views. In the early modern period, the term "atheist" was often applied broadly to those who believed in God but not in divine providence, or whose beliefs were deemed inconsistent with orthodox Christianity. In this extended sense, Hobbes indeed held positions that strongly diverged from the prevailing church teachings.

For instance, Hobbes repeatedly argued that there are no incorporeal substances, asserting that all things-including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell-are corporeal, or matter in motion. He maintained that "though Scripture acknowledge spirits, yet doth it nowhere say, that they are incorporeal, meaning thereby without dimensions and quantity," a view he claimed to derive from Tertullian. Like John Locke, he also stated that true revelation could never contradict human reason and experience. However, he also argued that people should accept revelation and its interpretations for the same reason they should accept the commands of their sovereign: to avoid war and maintain social order.

During his Grand Tour in Venice, Hobbes became acquainted with Fulgenzio Micanzio, a close associate of Paolo Sarpi, who had famously written against the papacy's claims to temporal power. Micanzio and Sarpi argued that God willed human nature, and that human nature itself indicated the autonomy of the state in temporal affairs. Upon his return to England in 1615, William Cavendish maintained correspondence with Micanzio and Sarpi, and Hobbes translated Sarpi's letters from Italian, which circulated within the Duke's intellectual circle.

Hobbes was openly critical of the Catholic Church's suppression of science and reason, citing the cases of Giordano Bruno (burned at the stake) and Galileo Galilei (prosecuted by the Inquisition). He believed that the Bible needed to be reinterpreted to align with the age of science and reason. He argued that if academic opinions, such as the Earth's movement, caused public disorder, it was the state's responsibility, not the church's, to suppress them using political authority. He viewed the church's attempt to act on divine authority in such matters as a usurpation of power. Hobbes famously declared, "Theology is the kingdom of darkness," and likened religions to "pills, which must be swallowed whole without chewing."

4.3. Views on Science and Mathematics

Hobbes's intellectual pursuits extended significantly into the realms of science and mathematics, where his mechanistic philosophy guided his inquiries. His initial area of study was the physical doctrine of motion and physical momentum, though he generally disdained experimental work in physics. He conceived a grand system of thought that would explain the phenomena of Body, Man, and the State in terms of motion and mechanical action.

He published several controversial writings on mathematics, particularly in geometry. In his 1655 work, De Corpore, Hobbes presented an erroneous proof of the squaring the circle, which sparked a lengthy and acrimonious public dispute with the prominent mathematician John Wallis. This controversy, which lasted for nearly a quarter of a century with Hobbes refusing to admit his error until his death, became one of the most infamous feuds in the history of mathematics. Hobbes also openly opposed the existing academic arrangements and criticized the system of the traditional universities in Leviathan.

Hobbes's interest in geometry was profound, stemming from his exposure to Euclid's Elements during his travels in France between 1629 and 1631. He adopted Euclid's deductive method as a primary approach for his own philosophical and scientific inquiries. However, his strong adherence to a mechanistic worldview also led him to criticize the experimentalism of figures like Robert Boyle and to deny the existence of a vacuum, a stance that ultimately prevented him from becoming a member of the Royal Society.

His philosophical contributions also include being recognized as the first modern philosopher in the field of sensationalism, a view that posits all mental states, especially human cognition, derive from the composition or association of mere sensations or feelings. Furthermore, Hobbes's mechanistic understanding of human behavior, often referred to as "social physics," influenced later thinkers like Montesquieu, who sought to apply empirical observation and "purify" the study of law from subjective value judgments.

5. Reception and Legacy

Thomas Hobbes's ideas generated immediate and intense debate, shaping the trajectory of Western philosophy and political thought for centuries. His work, particularly Leviathan, sparked both fervent praise and sharp criticism, establishing him as a pivotal figure in the intellectual history of the modern era.

5.1. Influence on Later Thought

Hobbes's writings, especially Leviathan, profoundly influenced subsequent political and moral philosophy in England and had a strong impact across Continental Europe. One notable philosopher influenced by Hobbes was Baruch Spinoza, particularly in his political views and his approach to interpreting the Bible.

Hobbes is also recognized as one of the earliest and most influential philosophers in the ongoing debate between free will and determinism. Additionally, he is considered a crucial philosopher of language, holding the view that language serves not only to describe the world but also to indicate behaviors and to bind promises and contracts. His work was foundational for the study of contractarianism, a branch of moral and political theory that utilizes the idea of the social contract. Hobbes is regarded as a pioneer of one of the two major moral arguments for the social contract, the other being that developed by Immanuel Kant. He is also considered the first modern philosopher in the field of sensationalism, which posits that all mental states originate from sensations.

His understanding of human beings as masses and motions obeying the same physical laws as other matter remains influential, as does his concept of human nature driven by self-interested cooperation. The idea of a political community founded upon a "social contract" became a central topic in political philosophy. While Hobbes's ultimate conclusion was the necessity of absolute sovereignty, elements of his thought paradoxically laid some groundwork for later European liberalism. These include his emphasis on individual rights, the natural equality of all humans, the artificial (rather than divinely ordained) nature of political order, the view that all legitimate political power must be "representative" and based on the consent of the people, and a relatively liberal interpretation of law that allows individuals the freedom to do anything not explicitly forbidden by law. His "social physics," which sought to apply scientific principles to human behavior, also influenced thinkers like Montesquieu, who attempted to approach the study of law from a more empirical and objective standpoint.

5.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Hobbes's work, particularly Leviathan, was immediately controversial. It was seen by some Royalists as atheistic and by Republicans as advocating for despotism. His life and ideas were marked by several significant disputes:

- Debate with John Bramhall: In 1654, Bishop John Bramhall, a staunch Arminian, published Of Liberty and Necessity, a treatise directed at Hobbes. Hobbes replied, but his response was published without his permission, leading Bramhall to print their entire exchange in 1655. Hobbes countered in 1656 with The Questions Concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, which was significant for its clear exposition of determinism. Bramhall continued the debate in 1658 with Castigations of Mr Hobbes's Animadversions and The Catching of Leviathan the Great Whale.

- Dispute with John Wallis: Hobbes was critical of existing academic institutions and openly attacked the university system in Leviathan. His publication of De Corpore in 1655, which contained controversial mathematical views and an erroneous proof for the squaring of the circle, made him a target for mathematicians, most notably John Wallis. Hobbes and Wallis engaged in a quarter-century-long intellectual feud, characterized by polemics and name-calling, with Hobbes refusing to admit his mathematical error until his death. This became one of the most infamous feuds in mathematical history.

- Accusations of Atheism: Hobbes was frequently accused of atheism by his contemporaries, including Bramhall. He consistently defended himself against these charges, considering such accusations to be the "greatest defamation possible." His religious views, which included arguments against incorporeal substances and the idea that God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, diverged significantly from orthodox church teachings, fueling these controversies.

- Philosophical Criticisms:

- Lord Acton (19th century) critically stated that "power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely," suggesting that Hobbes's emphasis on power echoed the problematic views of Niccolò Machiavelli.

- The Japanese ethicist Tomoeda Takahiko criticized Hobbes's assertion that "man is wolf to man" as purely egoistic, aligning it with Machiavelli's view that international relations are characterized solely by deception and violence.

- The journal Economica dedicated an issue in 1929 to "Contemporary Critics of Thomas Hobbes."

- Carl Joachim Friedrich, a political scientist, noted the limitation in Hobbes's definition of authority as "the right to do any act," despite Hobbes also stating that "no one is bound by a contract to which he is not a party." Friedrich argued that Hobbes overly emphasized power as the foundation of politics.

- Philosopher B.W. Hauptli compiled Selected Criticisms of Hobbes and Ethical Egoism, highlighting ongoing philosophical critiques.

Hobbes's theory of the artificial state, which posited a state of nature similar to Calvinism from which an artificial state model emerged, was pioneering for modern state theory. Unlike earlier social contract theories that merely explained existing states as "domination-submission contracts," Hobbes introduced the novel perspective of state formation through a social contract among equal individuals. His emphasis on human natural reason as a driving force for the social contract also positioned his work as an early form of Enlightenment state theory. While John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau critically built upon Hobbes's social contract theory, a key distinction lies in their differing views on the state of nature: Hobbes believed natural law was incomplete in this state, whereas Locke and Rousseau assumed it was already enforced.

Modern interpretations of Hobbes's political theory generally fall into four main categories:

1. Absolutist Political Theory: This classical view argues that Hobbes's theory supports absolute monarchy, citing his concept of the social contract as an act of submission, the sovereign as a singular entity embodying state reason, and the sovereign's control over all domestic and international policies, including religion.

2. Modern Political Theory: This interpretation posits Hobbes's theory as modern and democratic, emphasizing his atheistic, materialistic, and rationalist worldview, his advocacy for equality, and his scientific method of constructing an artificial state from atomistic individuals.

3. Traditional Political Theory: This perspective suggests that Hobbes's political theory aligns with traditional Christian ethical thought, arguing that his natural law ideas were formed before Descartes's influence and that his religious references were rooted in faith.

4. State of Nature Political Theory: This view asserts that Hobbes's political theory is ultimately a theory of the state of nature and conflict, where natural law merely transforms individual conflict into state-level conflict, without fundamentally altering the state of struggle.

Among these, the first and second interpretations remain the most classical and influential in contemporary scholarship.