1. Overview

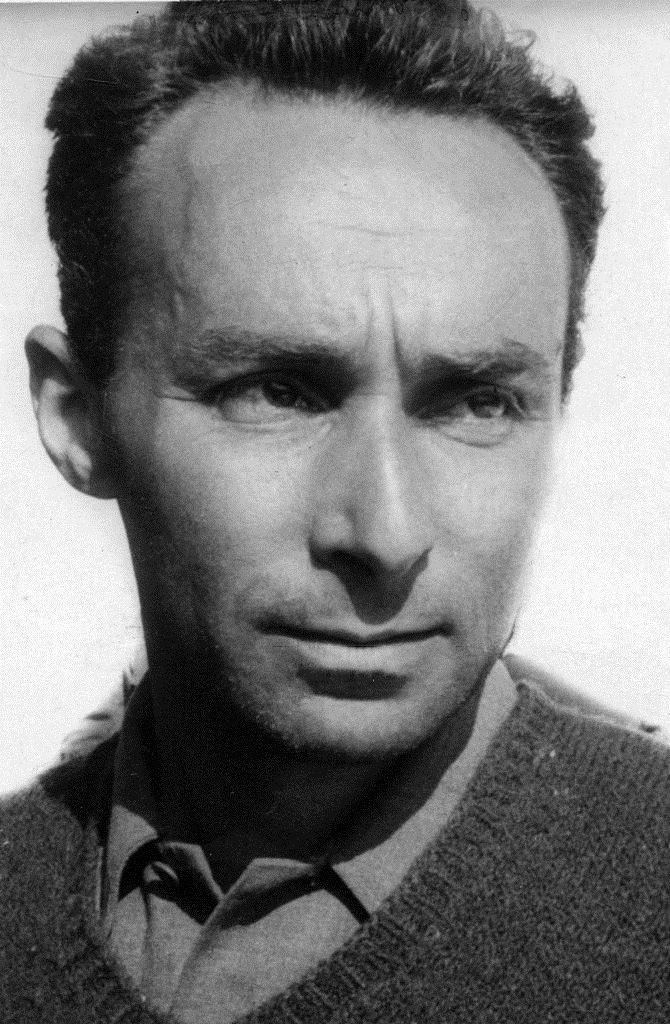

Primo Levi (ˈpriːmo ˈlɛːviItalian; 1919-1987) was a prominent Jewish-Italian chemist, partisan, Holocaust survivor, and writer. His multifaceted identity profoundly shaped his literary work, which extensively explored themes of humanity, memory, and survival in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Levi's writings, particularly his memoirs of the Auschwitz concentration camp experience, are considered seminal contributions to Holocaust literature and global discussions on human rights and historical responsibility. His work is recognized for its clear, unpretentious prose and its deep ethical and philosophical insights into the human condition under extreme duress.

2. Biography

Primo Levi's life unfolded against the backdrop of significant historical upheaval, from his early years under Italian Fascism to his harrowing experiences in Auschwitz and his subsequent dedication to bearing witness through literature.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Primo Michele Levi was born on July 31, 1919, in Turin, Italy, at Corso Re Umberto 75, into a liberal Jewish family. His father, Cesare Levi (1875-1942), was an electrical engineer who worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz, often abroad in Hungary. Cesare was an avid reader and autodidact. Levi's mother, Esterina (Ester Luzzati Levi, 1895-1991), known as Rina, was well-educated, having attended the Istituto Maria LetiziaItalian. She was also a keen reader, played the piano, and spoke fluent French. Their marriage was arranged by Rina's father, Cesare Luzzati, who gifted them the apartment at Corso Re Umberto, where Primo Levi lived for most of his life.

In 1921, his sister, Anna Maria, was born, and Levi remained close to her throughout his life. In 1925, he began attending the Felice RignonItalian primary school in Turin. A delicate and shy child, he excelled academically despite frequent absences due to illness, during which he was tutored at home. Summers were spent with his mother in the Waldensian valleys southwest of Turin. In September 1930, Levi entered the Massimo d'AzeglioItalian Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of schedule. As the youngest, shortest, and only Jewish student, he experienced bullying, which he found traumatic. In August 1932, he had his Bar Mitzvah at the local synagogue after two years at the Talmud Torah school. In 1933, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists, avoiding rifle drill by joining the ski division.

In July 1934, at age 15, he was admitted to the Liceo Classico D'Azeglio, a lyceum known for its anti-Fascist teachers, including philosopher Norberto Bobbio and novelist Cesare Pavese. Reading Concerning the Nature of Things by Sir William Bragg inspired Levi to become a chemist. In 1937, he faced a draft accusation from the Italian Royal Navy, which he avoided by enrolling in the Fascist militia. However, the passage of the Italian Racial Laws in 1938 led to his expulsion from the militia and barred new Jewish students from university. Levi, having matriculated a year early, was able to continue his studies. He graduated from the University of Turin with a degree in chemistry in mid-1941, with full marks and merit, though his certificate bore the remark: "of Jewish race."

The Manifesto of Race in July 1938 and the subsequent Italian Racial Laws of October 1938 stripped Italian Jews of their civil rights, public positions, and assets, prohibiting their books and barring them from publishing in Aryan-owned magazines. These laws radically altered the situation for Jews in Italy, particularly after Italy allied with Nazi Germany in 1939.

In 1939, Levi developed a passion for mountain hiking with his friend Sandro Delmastro, an experience he later described in The Periodic Table as a "new communion with earth and sky" that reconciled him with the world and converged with his "hunger to understand things that had driven [him] to chemistry." Sandro Delmastro, indifferent to Levi's Jewish origins, later became the first resistance fighter of the anti-Fascist Partito d'Azione's Piemont Military Command to die in action in April 1944.

Due to the racial laws and the escalating Fascist regime, Levi struggled to find an advisor for his Ph.D. dissertation on the Walden inversion. After graduating, he had difficulty securing a suitable permanent job. In December 1941, he informally accepted a job offer to work as a chemist at an asbestos mine in San Vittore, extracting nickel from mine spoil. He worked under a false name, aiding the German war effort, which faced nickel shortages for armaments. In March 1942, his father died, and in June, Levi left the mine to work in Milan for the Swiss pharmaceutical manufacturer Wander AG, researching an anti-diabetic from vegetable matter. He took this job with a Swiss company to evade Italian race laws.

2.2. World War II and Resistance

In July 1943, King Victor Emmanuel III deposed Benito Mussolini and appointed a new government, which prepared to sign the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies. When the armistice was announced on September 8, the Germans occupied northern and central Italy, liberated Mussolini, and established the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state. Levi returned to Turin to find his mother and sister in refuge at their holiday home in Chieri. As Jews, they were pursued by authorities and moved to Saint-Vincent in the Aosta Valley, then further up to Amay in the Col de Joux (Colle di JouxItalian), an area suitable for guerrilla warfare.

The Italian resistance movement intensified in German-occupied Italy. Levi and comrades formed a partisan group in the foothills of the Alps in October, hoping to affiliate with the liberal Giustizia e Libertà. Untrained, they were arrested by the Fascist militia on December 13, 1943. Believing he would be shot as an Italian partisan, Levi confessed to being Jewish, which led to his transfer to the internment camp at Fossoli near Modena.

Levi later recounted the conditions at Fossoli:

"We were given, on a regular basis, a food ration destined for the soldiers and at the end of January 1944, we were taken to Fossoli on a passenger train. Our conditions in the camp were quite good. There was no talk of executions and the atmosphere was quite calm. We were allowed to keep the money we had brought with us and to receive money from the outside. We worked in the kitchen in turn and performed other services in the camp. We even prepared a dining room, a rather sparse one, I must admit."

2.3. Auschwitz Experience

Fossoli was subsequently taken over by the Germans, who began organizing deportations of Jews to concentration and death camps in the east. On February 21, 1944, Levi and other inmates were transported in twelve cramped cattle trucks to Monowitz concentration camp, one of the three main camps within the Auschwitz concentration camp complex. Levi, assigned record number 174517, endured eleven months there before the camp was liberated by the Red Army on January 27, 1945. Before the Russian arrival, inmates were categorized as fit or unfit for work; an acquaintance of Levi's who declared himself unable to work was immediately killed. Of the 650 Italian Jews in his transport, Levi was one of only twenty who survived the camps. The average life expectancy for new arrivals was a mere three to four months.

Levi's basic knowledge of German, acquired from reading chemical publications, helped him adapt quickly to camp life without drawing undue attention. He traded bread for German lessons from a more experienced Italian prisoner, learning vital coping strategies. Crucially, Lorenzo Perrone, an Italian civilian bricklayer forced to work at Auschwitz, risked his life for six months to provide Levi with a smuggled soup ration and a piece of bread daily, a gesture that saved Levi's life.

Levi's chemical qualifications proved valuable to the Germans. In mid-November 1944, he secured a position as an assistant in IG Farben's Buna Werke laboratory, which aimed to produce synthetic rubber. This assignment spared him from the brutal hard labor in freezing outdoor temperatures. He also managed to steal materials from the laboratory and trade them for additional food, further aiding his survival.

Shortly before the camp's liberation by the Red Army, Levi contracted scarlet fever and was admitted to the camp's sanatorium (hospital). On January 18, 1945, as the Red Army approached, the SS hastily evacuated the camp, forcing all but the gravely ill on a long death march away from the front lines. This march resulted in the deaths of the vast majority of the remaining prisoners, but Levi's illness spared him this fate.

2.4. Return and Post-War Life

Although liberated on January 27, 1945, Levi did not reach Turin until October 19, 1945. After a period in a Soviet camp for former concentration camp inmates, he embarked on an arduous journey home. He traveled with former Italian prisoners of war who had been part of the Italian Army in Russia. This long railway journey, vividly described in his 1963 work The Truce, took him on a circuitous route through Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Hungary, Austria, and Germany, highlighting the millions of displaced people across Europe during that period.

Upon his return to Turin, Levi was almost unrecognizable due to malnutrition edema and a scrawny beard, wearing an old Red Army uniform. The following months were spent recovering physically, reconnecting with surviving friends and family, and seeking employment. Levi, however, suffered from the profound psychological trauma of his experiences. Unable to find work in Turin, he began looking in Milan, and during his train commutes, he started recounting his Auschwitz stories to fellow passengers.

At a Jewish New Year party in 1946, he met Lucia Morpurgo, who offered to teach him to dance; Levi fell in love with her. Around this time, he also began writing poetry about his time in Auschwitz. On January 21, 1946, he started working at DUCO, a Du Pont Company paint factory near Turin. He stayed in the factory dormitory during the week due to limited train service, which provided him with undisturbed time to write. He began the first draft of If This Is a Man, diligently scribbling notes on train tickets and scraps of paper as memories surfaced. By the end of February, he had ten pages detailing the last ten days between the German evacuation and the Red Army's arrival. Over the next ten months, the book took shape as he typed his recollections each night.

On December 22, 1946, the manuscript was complete. Lucia, who had reciprocated his love, helped him edit it for a more natural narrative flow. In January 1947, Levi began submitting the manuscript to publishers. It was rejected by Einaudi and, in the United States, by Little, Brown and Company, contributing to the neglect of his work in the US for four decades. The social wounds of the war were still too fresh, and Levi lacked a literary reputation. Eventually, he found a publisher, Franco Antonicelli, an amateur publisher and active anti-Fascist who supported the book's substance.

In June 1947, Levi left DUCO and partnered with his old friend Alberto Salmoni to open a chemical consultancy. Many of his experiences from this period later appeared in his writings. They primarily earned money by making and supplying stannous chloride for mirror makers, delivering the unstable chemical by bicycle. Attempts to create lipsticks from reptile excreta and colored enamel were transformed into short stories. Their laboratory accidents often filled the Salmoni house with unpleasant smells and corrosive gases.

In September 1947, Levi married Lucia. A month later, on October 11, If This Is a Man was published in a print run of 2,000 copies. In April 1948, with Lucia pregnant, Levi decided the independent chemist's life was too precarious and joined Accatti's family paint business, SIVA. Their daughter, Lisa, was born in October 1948.

During this time, his friend Lorenzo Perrone's health declined. Lorenzo, a civilian forced laborer in Auschwitz, had saved Levi's life by sharing his rations. Levi contrasted Lorenzo with everyone else in the camp, as someone who preserved his humanity. After the war, Lorenzo struggled with his memories and succumbed to alcoholism. Levi made several attempts to help him, but Lorenzo died in 1952. In gratitude, Levi named both his children, Lisa Lorenza and Renzo, after him.

In 1950, Levi was promoted to Technical Director at SIVA, where he served as principal chemist and troubleshooter, traveling internationally. During his trips to Germany, he deliberately wore short-sleeved shirts to ensure German businessmen and scientists saw his concentration camp number tattooed on his arm. He also became involved in organizations dedicated to remembering the Holocaust, visiting Buchenwald in 1954 for the ninth anniversary of its liberation and regularly recounting his experiences at such events. His son, Renzo, was born in July 1957.

2.5. Beginnings of Literary Work

Primo Levi's literary career was born out of an urgent need to bear witness to the horrors he experienced in Auschwitz. Despite a positive review by Italo Calvino in L'Unità (L'UnitàItalian), If This Is a Man initially sold only 1,500 copies. However, in 1958, Einaudi, a major publisher, republished a revised version and promoted it, leading to wider recognition.

In 1958, Stuart Woolf, in close collaboration with Levi, translated If This Is a Man into English, published in the UK by Orion Press in 1959. In 1959, Heinz Riedt, under Levi's supervision, translated the book into German. This translation was particularly significant to Levi, as one of his primary motivations for writing the book was to make the German people confront what had been done in their name and accept at least partial responsibility.

2.6. Major Works

Levi began writing The Truce in early 1961. Published in 1963, almost 16 years after his first book, it won the first annual Premio Campiello (Premio CampielloItalian) literary award that year. It is often published in one volume with If This Is a Man because it chronicles his long and circuitous return journey through Eastern Europe from Auschwitz. As Levi's reputation grew, he regularly contributed articles to La Stampa (La StampaItalian), the Turin newspaper, striving to establish himself as a writer on subjects beyond his Auschwitz survival.

From 1963, Levi experienced significant bouts of depression, a condition now better understood in its link to trauma. He collaborated with the state broadcaster RAI on a radio play based on If This Is a Man in 1964, followed by a theatre production in 1966.

Under the pseudonym Damiano Malabaila, Levi published two volumes of science fiction short stories: Storie naturaliItalian (Natural Histories, 1966) and Vizio di formaItalian (Structural Defect, 1971). These works explored ethical and philosophical questions, imagining the societal implications of inventions that, while seemingly beneficial, could have serious consequences. Many of these stories were later collected and published in English as The Sixth Day and Other Tales.

In 1974, Levi transitioned into semi-retirement from SIVA to dedicate more time to writing and to escape the managerial responsibilities of the paint plant. In 1975, a collection of his poetry, L'osteria di BremaItalian (The Bremen Beer Hall), was published, later appearing in English as Shema: Collected Poems.

He wrote two other highly acclaimed memoirs: Lilìt e altri raccontiItalian (Moments of Reprieve, 1978) and Il sistema periodicoItalian (The Periodic Table, 1975). Moments of Reprieve focuses on characters he encountered during his imprisonment. The Periodic Table is a collection of mostly autobiographical short stories, including two fictional ones he wrote in 1941 while working at the asbestos mine. Each story is named after a chemical element, and its subject matter relates to that element. On October 19, 2006, the Royal Institution in London declared The Periodic Table the best science book ever written.

In 1977, at 58, Levi fully retired from SIVA to become a full-time writer. His book, La chiave a stella (1978), published in the US as The Monkey Wrench and in the UK as The Wrench, defies easy categorization. It is a collection of stories about work and workers, narrated by a character resembling Levi, or a novel formed by linked stories. Set in the Fiat-run Russian company town of Togliattigrad, it portrays the engineer as a heroic figure. The stories, many drawn from Levi's personal experience, involve solving industrial problems through troubleshooting, underpinned by the philosophy that pride in one's work is essential for fulfillment. The Wrench won the Strega Prize in 1979, broadening Levi's audience in Italy, though some left-wing critics regretted its lack of focus on harsh working conditions at Fiat.

In 1984, Levi published his only novel, If Not Now, When?, which recounts the journey of a group of Jewish partisans behind German lines during World War II. Their goal is to survive, continue fighting, and ultimately reach Palestine to contribute to the development of a Jewish national home. The partisan band travels through Poland and into German territory, where surviving members are officially received as displaced persons by the Western Allies. Eventually, they reach Italy on their way to Palestine. The novel won both the Premio Campiello (Premio CampielloItalian) and the Premio Viareggio (Premio ViareggioItalian). This book was inspired by events during Levi's train journey home after liberation, as narrated in The Truce, particularly his encounter with a group of Zionists whose strength, resolve, organization, and sense of purpose deeply impressed him.

Levi became a major literary figure in Italy, and his books were translated into many languages. The Truce became a standard text in Italian schools. In 1985, he undertook a demanding 20-day speaking tour in the United States, accompanied by Lucia. In the Soviet Union, his early works were censored because he depicted Soviet soldiers as slovenly rather than heroic. In Israel, many of his works were not translated and published until after his death.

In March 1985, Levi wrote the introduction to the re-publication of the autobiography of Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz from 1940 to 1943. Levi described reading it as "agony," stating it was "filled with evil." Also in 1985, a volume of his essays, previously published in La Stampa (La StampaItalian), was released under the title L'altrui mestiereItalian (Other People's Trades). These essays, which Levi would write and release to La Stampa weekly, covered diverse topics from book reviews and natural phenomena to fictional short stories.

In 1986, his book I sommersi e i salvatiItalian (The Drowned and the Saved) was published. In this work, Levi analytically explored why people behaved as they did in Auschwitz and why some survived while others perished. He presented evidence and posed questions without making judgments. For instance, one essay examines what he termed "the grey zone": those Jews who performed "dirty work" for the Germans and maintained order among prisoners. He questioned what could transform a concert violinist into a callous taskmaster. Also in 1986, a collection of short stories, previously published in La Stampa (La StampaItalian), was compiled and published as Racconti e SaggiItalian, some of which appeared in the English volume The Mirror Maker.

At the time of his death in April 1987, Levi was working on another selection of essays titled The Double Bond, structured as letters to "La Signorina"Italian. These highly personal essays, of which approximately five or six chapters exist, were partially tracked down by biographer Carole Angier, who also noted that some might have been destroyed by Levi's close friends to whom he had given them.

2.7. Literary Recognition and Awards

Primo Levi's literary contributions earned him significant acclaim and numerous awards throughout his career. His works were widely translated, with the German translation of If This Is a Man being particularly meaningful to him. He was awarded the Premio Campiello in 1963 for The Truce and again in 1982 for If Not Now, When?. He received the Strega Prize in 1979 for The Wrench and the Premio Viareggio in 1982 for If Not Now, When?. His work, especially The Periodic Table, gained international recognition when the Royal Institution in London named it the best science book ever written in 2006. Despite being frequently referred to as a "Holocaust writer," a label he disliked, his writings are considered among the most important on the subject, profoundly contributing to the memory and understanding of the disaster.

2.8. Posthumous Publications

In March 2007, Harper's Magazine published an English translation of Levi's story "Knall"Italian, originally from his 1971 book Vizio di formaItalian, which describes a fictitious weapon lethal at close range but harmless beyond a meter. A Tranquil Star, a collection of seventeen stories translated by Ann Goldstein and Alessandra Bastagli, was published in April 2007. In 2015, Penguin published The Complete Works of Primo Levi, edited by Ann Goldstein, marking the first time Levi's entire oeuvre was translated into English.

3. Views and Philosophy

Primo Levi's experiences deeply informed his intellectual contributions, leading to profound reflections on historical events, human nature, and societal ethics.

3.1. Holocaust and Historical Responsibility

Levi vigorously rejected historical revisionism that sought to draw parallels between Nazism and Stalinism, such as the arguments made during the Historikerstreit by figures like Andreas Hillgruber and Ernst Nolte. He maintained that the Nazi extermination camps (KonzentrationslagerGerman) and the Soviet gulag system were fundamentally incomparable. While acknowledging the "lugubrious comparison between two models of hell," Levi emphasized that the death rate in Stalin's gulags was at worst 30%, whereas in the Nazi extermination camps, he estimated it to be 90-98%.

His view was that the Nazi death camps and the attempted annihilation of the Jews constituted a horror unique in history. The goal was the complete destruction of a race by one that saw itself as superior, a process that was highly organized and mechanized, even degrading Jewish victims to the point of using their ashes as materials for paths. The purpose of the Nazi LagerGerman was the extermination of the Jewish race in Europe, and no one could renounce Judaism, as the Nazis considered Jews a racial group rather than a religious group. Levi, like most of Turin's Jewish intellectuals, had not been religiously observant before World War II, but the Italian racial laws and the Nazi camps indelibly impressed his identity as a Jew upon him. He noted that almost all children deported to the camps were murdered, an atrocity unique among all historical human atrocities.

3.2. Human Nature, Memory, and Survival

Levi's writings are a profound exploration of human behavior under extreme conditions, the intricate role of memory, and the complex challenges of survival. He delved into the concept of "the grey zone," which describes the morally ambiguous space occupied by prisoners who collaborated with their oppressors to survive. He meticulously analyzed the psychological and ethical compromises made by individuals, such as the Sonderkommandos or intermediate functionaries in the camps, without making definitive judgments. Instead, he presented evidence and posed questions, inviting readers to confront the complexities of human agency and complicity in unimaginable circumstances. His work emphasizes the fragility of human dignity and the persistent, often painful, struggle to retain one's humanity and memory in the face of systematic dehumanization.

3.3. Views on the German People

According to biographer Ian Thomson, Levi initially excluded experiences with helpful Germans from If This Is a Man, including "collective condemnations, coloured by the author's rage, of the German people." However, Levi's opinion of Germans evolved through his 17-year friendship with Hety Schmitt-Maas, a German woman whose family had suffered for their anti-Nazi beliefs. They corresponded until Schmitt-Maas's death in 1983, discussing "their shared hatred of Nazism."

Nearly forty years after If This Is a Man was published, Levi stated that he did not hate the German people, considering such collective hatred too similar to Nazism. However, he firmly declared that he did not forgive "the culprits." He believed that while most Germans were aware of the concentration camps, they did not know the full extent of the atrocities, largely because "most Germans didn't know because they didn't want to know. Because, indeed, they wanted not to know."

4. Personal Life

Primo Levi's personal life was intertwined with his public and literary endeavors. He married Lucia Morpurgo in September 1947. They had two children, a daughter named Lisa (born October 1948) and a son named Renzo (born July 1957). In a gesture of profound gratitude, Levi named both his children after Lorenzo Perrone, the Italian bricklayer who risked his life to provide Levi with extra food in Auschwitz, a kindness that saved him. His family, particularly his elderly mother and mother-in-law, with whom he lived in his later years, were a significant part of his daily life, though also a source of considerable responsibility.

5. Death

The circumstances surrounding Primo Levi's death remain a subject of debate, highlighting the enduring impact of his Holocaust experience.

5.1. Circumstances of Death

Primo Levi died on April 11, 1987, after falling from the interior landing of his third-story apartment in Turin to the ground floor below. The coroner officially ruled his death a suicide.

5.2. Controversy Over Cause of Death

Three of Levi's biographers-Carole Angier, Ian Thomson, and Myriam Anissimov-concurred with the official ruling of suicide. In his later life, Levi had indeed indicated that he was suffering from depression. Factors contributing to this likely included the responsibility for his elderly mother and mother-in-law, with whom he was living, and the lingering traumatic memories of his Auschwitz experiences. The chief rabbi of Rome, Elio Toaff, stated that Levi telephoned him ten minutes before the incident, expressing the impossibility of looking at his ill mother without recalling the faces of people stretched out on benches in Auschwitz. Fellow Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel famously remarked at the time, "Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later."

However, several of Levi's friends and associates have disputed the suicide ruling, attributing his death to an accidental fall. The Oxford sociologist Diego Gambetta noted that Levi left no suicide note or any other indication that he was considering suicide. Documents and testimonies suggested that he had plans for both the short and longer term at the time of his death. In the days preceding his death, he had complained to his physician of dizziness, a side effect of an operation he had undergone approximately three weeks earlier. After visiting the apartment complex, Gambetta suggested that Levi might have lost his balance and fallen accidentally. Nobel laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini, a close friend of Levi, agreed, stating, "As a chemical engineer, he might have chosen a better way [of exiting the world] than jumping into a narrow stairwell with the risk of remaining paralyzed."

6. Legacy and Impact

Primo Levi's enduring legacy is marked by his profound contributions to Holocaust memory, literature, and ethical discourse, continuing to influence generations of thinkers and artists.

6.1. A Leading Voice in Holocaust Literature

Levi is widely regarded as one of the most important voices in Holocaust literature, despite his personal dislike for the label "Holocaust writer." His works have significantly contributed to the memory and understanding of that catastrophe. Philip Roth eulogized him as someone who "set out systematically to remember the German hell on earth, steadfastly to think it through, and then to render it comprehensible in lucid, unpretentious prose." Martin Amis credited Levi's work with aiding his own novel, The Zone of Interest, calling Levi "the visionary of the Holocaust, its presiding spirit and the most perceptive of all writers on this subject."

6.2. Posthumous Honors and Institutions

Primo Levi's lasting contributions have been recognized through numerous posthumous honors and the establishment of institutions in his name:

- In 1995, five health and human rights organizations established the Primo Levi Center in Paris to provide services to torture survivors, naming it after Levi because his name is "synonymous with the refusal of inhuman, cruel and degrading treatment."

- The Primo Levi Center, a non-profit organization dedicated to studying the history and culture of Italian Jewry, was established in New York City in 2003.

- In 2008, the City of Turin and other partners established the International Primo Levi Studies Center to preserve and promote Levi's legacy.

- Beginning in 2017, the Primo Levi Prize has been awarded by the German Chemical Society and the Italian Chemical Society to honor chemists for their commitment to human rights.

- In 2019, Levi's 100th birthday was commemorated worldwide, including in the United States, Portugal, and Italy.

- The SIVA factory, where Levi worked as a chemist and technical director, has been transformed into the Museo della Chimica (Chemistry Museum) for children. Levi's former office now houses an exhibit dedicated to his life.

6.3. Cultural and Intellectual Influence

Levi's writings and ideas have had a broad impact on literature, philosophy, and public discourse, particularly concerning ethics, memory, and social justice.

- Till My Tale is Told: Women's Memoirs of the Gulag (1999) uses a part of the quatrain by Coleridge quoted by Levi in The Drowned and the Saved as its title.

- Christopher Hitchens' book The Portable Atheist is dedicated to Levi's memory, quoting Levi from The Drowned and the Saved: "I too entered the Lager as a nonbeliever, and as a nonbeliever I was liberated and have lived to this day."

- A quotation from Levi's poem "Song of Those Who Died in Vain" appears on the sleeve of the second album by the Welsh rock band Manic Street Preachers, titled Gold Against the Soul.

- Magician David Blaine has Primo Levi's Auschwitz camp number, 174517, tattooed on his left forearm.

- In Lavie Tidhar's novel A Man Lies Dreaming, the protagonist encounters Levi and Ka-Tzetnik in Auschwitz, where they discuss how to write about the Holocaust, with Levi advocating for an "accurate and dispassionate" approach.

- In the pilot episode of Black Earth Rising, Rwandan genocide survivor Kate Ashby references Levi's book when discussing her own struggles with survivor's guilt and suicide attempts.

- The last track on The Noise by Peter Hammill is entitled "Primo on the Parapet."

7. Works

| Title | Year | Type | English language translations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Se questo è un uomoItalian | 1947 and 1958 | Memoir | If This Is a Man (US: Survival in Auschwitz) |

| La treguaItalian | 1963 | Memoir | The Truce (US: The Reawakening) |

| Storie naturaliItalian (as Damiano Malabaila) | 1966 | Short stories | The Sixth Day and Other Tales |

| Vizio di formaItalian | 1971 | Short stories | Mainly in The Sixth Day and Other Tales. Some stories are in A Tranquil Star |

| Il sistema periodicoItalian | 1975 | Short stories | The Periodic Table |

| L'osteria di BremaItalian | 1975 | Poems | In Collected Poems |

| La chiave a stellaItalian | 1978 | Novel | The Wrench (US: The Monkey's Wrench) |

| Lilìt e altri raccontiItalian | 1981 | Short stories | Part 1: Moments of Reprieve. Some stories from Parts 2 and 3 are in A Tranquil Star |

| La ricerca delle radiciItalian | 1981 | Personal anthology | The Search for Roots: A Personal Anthology |

| Se non ora, quando?Italian | 1982 | Novel | If Not Now, When? |

| Ad ora incertaItalian | 1984 | Poems | In Collected Poems |

| L'altrui mestiereItalian | 1985 | Essays | Other People's Trades |

| I sommersi e i salvatiItalian | 1986 | Essays | The Drowned and the Saved |

| Racconti e SaggiItalian | 1986 | Essays | The Mirror Maker |

| Conversazioni e interviste 1963-1987Italian | 1997 | Various (posthumous) | Conversations with Primo Levi and The Voice of Memory: Interviews, 1961-1987 |

| The Black Hole of Auschwitz | 2005 | Essays (posthumous) | The Black Hole of Auschwitz |

| Auschwitz Report | 2006 | Factual (posthumous) | Auschwitz Report |

| A Tranquil Star | 2007 | Short stories (posthumous) | A Tranquil Star |

| The Magic Paint | 2011 | Short stories | The Magic Paint (Selection from A Tranquil Star) |

8. Adaptations

Primo Levi's powerful narratives have been adapted into various artistic mediums, extending their reach and impact.

- Five of Levi's poems (Shema, 25 Febbraio 1944, Il canto del corvo, Cantare, and Congedo) were set to music by Simon Sargon in the song cycle Shema: 5 Poems of Primo Levi in 1987. In 2021, this work was performed by Megan Marie Hart during the opening event of the festival year "1700 Years of Jewish Life in Germany" (1700 Jahre jüdisches Leben in DeutschlandGerman), commemorating the first documented mention of Jewish communities in present-day Germany.

- The 1997 film La TreguaItalian (The Truce), starring John Turturro, was adapted from Levi's 1963 memoir of the same title. It recounts Levi's long journey home with other displaced people after his liberation from Auschwitz.

- If This Is a Man was adapted by Antony Sher into a one-man stage production titled Primo in 2004. A version of this production was broadcast on BBC Four in the UK on September 20, 2007.

- The 2001 film The Grey Zone is based on the second chapter of The Drowned and the Saved.