1. Early Life and Education

Peter Carl Fabergé's early life and extensive education laid the foundation for his illustrious career, instilling in him a deep appreciation for craftsmanship and artistic innovation.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Peter Carl Fabergé was born on May 30, 1846, in Saint Petersburg, Russia. His father was Gustav Fabergé, a Baltic German jeweller, and his mother was Charlotte Jungstedt, the daughter of Danish painter Karl Jungstedt. The Fabergé family had a rich heritage, with Gustav Fabergé's paternal ancestors being Huguenots who originated from La Bouteille, Picardy, France. They fled France following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, first settling near Berlin, Germany, and then moving to Pernau County (modern-day Pärnu, Estonia) in 1800, which was then part of the Livonia Governorate within the Russian Empire.

1.2. Education and European Travels

In 1860, Gustav Fabergé retired from his jewelry business and relocated with his family to Dresden, the capital of Saxony, entrusting the House of Fabergé in Saint Petersburg to his business partner, Hiskias Pendin. Carl enrolled at the Dresden Handelsschule, a trade school where sons of Saxon merchants studied business administration. His brother, Agathon Fabergé, was born in Dresden two years later in 1862 and also attended school there.

Carl was sent to England to learn English and subsequently embarked on an extensive Grand Tour across Europe, which lasted until 1872. During this period, he received tuition from respected goldsmiths in Germany, France, and England. He attended a course at Schloss's Commercial College in Paris and visited the galleries of Europe's leading museums, studying their collections of decorative arts. He also apprenticed with the jeweler Josef Friedman of Frankfurt-am-Main, whose jewels were highly regarded in the German principalities. This comprehensive training and exposure to European artistic traditions greatly influenced his developing style. Fabergé returned to Saint Petersburg in 1864 and joined his father's firm. Although only 18, he continued his education under the tutelage of Hiskias Pendin. He also cultivated friendships with members of the directorate of the Hermitage Museum and began unpaid work there in 1867, further deepening his knowledge of historical jewelry and design.

2. Career and Business Development

Peter Carl Fabergé's career was marked by a transformative vision that elevated his family's jewelry business from a local firm to an internationally acclaimed house of artistic luxury.

2.1. Taking Over the Family Business

In 1872, Peter Carl Fabergé married Augusta Julia Jacobs. In the same year, he officially took over his father's firm, though the year 1870 is also widely but erroneously quoted for this succession. His first child, Eugène Fabergé, was born in 1874, followed by Agathon Fabergé in 1876, Alexander in 1877, and Nicholas in 1884. Another son, Nikolai, died in infancy between 1881 and 1883.

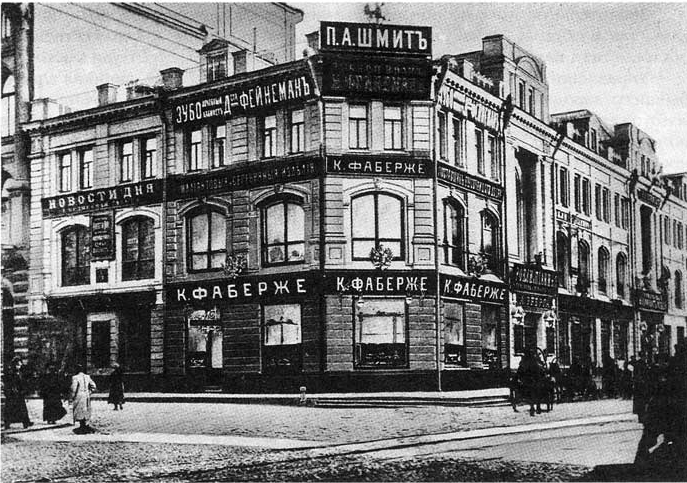

During the 1870s, the company was actively involved in cataloging, repairing, and restoring objects within the Hermitage Museum, which provided Fabergé with invaluable exposure to historical masterpieces. In 1881, the business relocated to a larger, more prominent street-level premises at 16/18 Bolshaya Morskaya. Fabergé immediately began implementing changes to transform the firm from what his son Eugène described as "a dealer in petty jewelry and spectacles." His European travels had inspired him to create pieces that transcended mere monetary value, as he later articulated: "Expensive things interest me little if the value is merely in so many diamonds or pearls."

2.2. Master Goldsmith and Imperial Patronage

By 1881, Carl Fabergé had garnered sufficient recognition among his peers to be appointed "Master of the Second Guild," a designation that marked him as a merchant or retailer rather than solely a craftsman. This prestigious title also exempted him from having to submit his pieces for official testing when using his own hallmark alongside that of the firm. Upon the death of Hiskias Pendin in 1882, Carl Fabergé assumed sole responsibility for managing the company and was formally acknowledged as its head. At this time, the firm employed approximately 20 people.

A pivotal moment for the firm occurred in 1882 when Carl and his brother Agathon Fabergé achieved widespread acclaim at the Pan-Russian Exhibition of Industry and the Arts held in Moscow. Carl was awarded a gold medal and the Order of Saint Stanislas. His prior work at the Hermitage, which included the restoration of 4th-century Greek and Scythian jewelry, had led to his invitation to the exhibition. Fabergé had also received permission to copy and incorporate the designs of these ancient artifacts, which became a central focus of his display. The magazine Niva lauded his contributions, stating: "Mr Fabergé opens a new era in the art of jewellery..." The Empress Maria Feodorovna herself honored Fabergé by purchasing a pair of cufflinks featuring cicadas, believed in Ancient Greek lore to bring luck. Despite this imperial recognition, Fabergé was initially one of many jewelers supplying the Russian court, with his firm receiving a comparatively modest 6.40 K RUB in 1883, the smallest sum paid among at least five firms mentioned in imperial accounts.

2.3. Early Successes and Artistic Innovation

The firm's breakthrough into sustained imperial patronage came in 1885 with the creation of the very first Fabergé egg, known as the Hen Egg. This exquisite piece was a gift from Emperor Alexander III to his wife, Maria Feodorovna, for Orthodox Easter on March 24. The Empress was so delighted that on May 1, the Emperor bestowed upon the firm the prestigious title of "Supplier to the Imperial Court." This appointment granted Fabergé full personal access to the invaluable Hermitage Collection, providing him with a rich source of inspiration to develop his unique artistic style.

Influenced by the jeweled bouquets crafted by 18th-century goldsmiths such as Jean-Jacques Duval and Jérémie Pauzié, Fabergé reinterpreted their ideas, combining them with his meticulous observations and a fascination for Japanese art. This fusion led to a revival of the lost art of enameling and a new emphasis on setting each gemstone to its best visual advantage. It was common for Agathon Fabergé, a highly talented and creative designer who joined the business from Dresden, to create ten or more wax models to explore all design possibilities before finalizing a piece. Shortly after Agathon joined, the House introduced objects deluxe: a range of gold bejeweled items embellished with enamel, from electric bell pushes to cigarette cases, encompassing a broader category of objects de fantaisie. This period marked a significant shift from traditional jewelry to more artistic and imaginative creations, characterized by lightness and elegance in design.

3. Major Works and International Recognition

Fabergé's most celebrated creations, particularly the Imperial Easter Eggs, cemented his reputation as a master jeweler, while his business expansion and participation in international exhibitions brought him global acclaim.

3.1. The Imperial Easter Eggs

Following the Empress Maria Feodorovna's enthusiastic response to the Hen Egg, Emperor Alexander III commissioned the House of Fabergé to create a unique Easter egg as a gift for her every year. From 1887 onwards, the Emperor granted Carl Fabergé complete artistic freedom regarding the egg designs, which consequently became increasingly elaborate. According to Fabergé family tradition, not even the Emperor knew the final form the eggs would take; the only stipulation was that each egg must be unique and contain a surprise. While Fabergé had considerable artistic liberty, Alexander III did collaborate with him to some extent on certain designs.

Upon Alexander III's death in 1894, his son, Emperor Nicholas II, continued this tradition, expanding it by commissioning two eggs annually: one for his mother, Maria Feodorovna (who ultimately received a total of 30 such eggs), and another for his wife, Alexandra (who received 20). These annual Easter gifts are now known as the Imperial Easter Eggs, distinguishing them from other jeweled eggs Fabergé produced. This cherished tradition persisted until the October Revolution of 1917, which led to the execution of the entire Romanov dynasty and the confiscation of the eggs and other imperial treasures by the interim government. The final two eggs commissioned were never delivered or paid for.

The Imperial Easter Eggs are renowned for their intricate craftsmanship, hidden surprises, and historical significance. The following is a list of the Imperial Easter Eggs, including their creation year and current known location:

- 1885 Hen (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1886 Hen with Sapphire Pendant (Lost)

- 1887 Blue Serpent Clock (Prince Rainier III of Monaco Collection, Monaco)

- 1888 Cherub with Chariot (Lost)

- 1889 Necessaire (Lost)

- 1890 Danish Palaces (New Orleans Museum of Art, USA)

- 1891 Memory of Azov (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1892 Diamond Trellis (Private collection)

- 1893 Caucasus (New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA)

- 1894 Renaissance (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1895 Rosebud (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1895 Twelve Monograms (Hillwood Museum, Washington, D.C., USA)

- 1896 Revolving Miniatures (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, USA)

- 1896 Alexander III (Lost)

- 1897 Coronation (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1897 Mauve Enamel (Lost)

- 1898 Lilies of the Valley (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1898 Pelican (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA)

- 1899 Bouquet of Lilies Clock (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1899 Pansy (Private collection)

- 1900 Cockerel (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1901 Basket of Wild Flowers (Royal Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

- 1901 Gatchina Palace (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA)

- 1902 Clover (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1902 Empire Nephrite (Lost)

- 1903 Peter the Great (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA)

- 1903 Danish Jubilee (Lost)

- 1904 Uspensky Cathedral (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1906 Swan (Edouard and Maurice Sandoz Foundation, Switzerland)

- 1907 Rose Trellis (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA)

- 1907 Cradle with Garlands (Private collection)

- 1908 Alexander Palace (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1908 Peacock (Edouard and Maurice Sandoz Foundation, Switzerland)

- 1909 Standart (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1909 Alexander II Commemorative (Lost)

- 1910 Alexander III Equestrian (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1910 Colonnade (Royal Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

- 1911 Bay Tree (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1911 Fifteenth Anniversary (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1912 Tsarevich (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA)

- 1912 Napoleonic (New Orleans Museum of Art, USA)

- 1913 Romanov Tercentenary (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1913 Winter (Private collection)

- 1914 Mosaic (Royal Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

- 1914 Grisaille (Hillwood Museum, Washington, D.C., USA)

- 1915 Red Cross with Imperial Portraits (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, USA)

- 1915 Red Cross with Triptych (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

- 1916 Cross of St. George (Vekselberg Collection, Russia)

- 1916 Steel Military (Kremlin Armoury Museum, Moscow)

- 1917 Constellation Egg (Fersman Mineralogical Institute, Moscow)

- 1917 Karelian Birch Egg (Russian National Museum, Moscow)

3.2. Other Creations and Business Expansion

While the House of Fabergé is most famously associated with the Imperial Easter Eggs, the firm produced a vast array of other objects, ranging from elaborate silver tableware to exquisite fine jewelry. These items were consistently of exceptional quality and beauty, embodying the firm's commitment to artistic excellence. Until its departure from Russia during the revolution, Fabergé's company grew to become the largest jewelry business in the country.

The Saint Petersburg headquarters comprised several workshops, each responsible for overseeing an item from its initial design through all manufacturing stages. The Moscow branch, established in 1887, primarily functioned as a commercial center. The business further expanded with branches in other major cities, including Odessa (1890), London (1903), and Kiev (1905). The firm employed approximately 500 people across its operations. Between 1882 and 1917, Fabergé produced an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 items of jewelry, silver, and other objets de fantaisie. These creations drew inspiration from diverse artistic periods, including Louis XV, Louis XVI, Classical, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, and Art Nouveau, alongside traditional Russian art. Designs frequently featured floral motifs, intricate carvings, and animal figures, often incorporating precious materials like gold, silver, malachite, lapis lazuli, and diamonds. Master craftsmen like Michael Evlampievich Perchin (whose works from 1886 to 1903 bore the "MP" mark) and Henrik Wigström (whose works were marked "HW") were instrumental in the firm's production of these masterpieces.

3.3. International Acclaim

Fabergé's exceptional craftsmanship gained international recognition when his work represented Russia at the 1900 World's Fair in Paris. As Carl Fabergé was a member of the jury, the House of Fabergé exhibited hors concours (without competing). Nevertheless, the House was awarded a gold medal, and the city's jewelers acknowledged Carl Fabergé as a maître (master). Furthermore, France honored Carl Fabergé with one of its most prestigious awards, appointing him a knight of the Legion of Honour. Two of Carl's sons and his head workmaster were also recognized with honors. Commercially, the exposition proved to be a resounding success, leading the firm to acquire a significant number of new orders and clients from around the world.

4. The End of the House of Fabergé and Exile

The tumultuous historical events of the early 20th century, particularly the Russian Revolution, profoundly impacted Fabergé's business and forced him into exile.

4.1. Impact of Revolution

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the House of Fabergé submitted proposals for wartime production. The firm received approval the following year, and production of military orders commenced, continuing until the October Revolution in 1917. In 1916, the House of Fabergé transitioned into a joint-stock company under the name C. Fabergé, with a fixed capital of 3.00 M RUB.

As a direct consequence of the revolution, the business was initially managed by a Committee of Employees. However, in 1918, Fabergé himself closed the workshops after officials of the new government requested him to cease operations. The firm was subsequently nationalized by the Bolsheviks, and its assets, including shares, were confiscated by early October 1918. Fabergé reportedly requested only ten minutes to gather his personal belongings before leaving. The vast majority of the firm's jewels were destroyed or lost in the aftermath of the revolution.

4.2. Exile and Final Years

Peter Carl Fabergé managed to escape Russia in September 1918, traveling under disguise as a courier with the British legation. He initially fled to Riga on the last diplomatic train. As the revolution spread to Latvia by mid-November, he then escaped to Germany, settling first in Bad Homburg and later in Wiesbaden. His eldest son, Eugène Fabergé, traveled with his mother through snow-covered forests by sleigh and on foot, arriving in Finland in December 1918. In June 1920, Eugène joined his father in Wiesbaden, and together they sought refuge in Switzerland, where other family members had gathered at the Hotel Bellevue in Pully, near Lausanne.

Peter Carl Fabergé never fully recovered from the profound shock and heartbreak caused by the Russian Revolution and the loss of his beloved country and business. During his exile, he frequently expressed, "What is there to live for?" He died at the Hotel Bellevue in Lausanne, Switzerland, on September 24, 1920, at the age of 74. His family believed he died of a broken heart. His wife, Augusta, passed away in 1925. In 1929, their son Eugène Fabergé brought his father's remains from Lausanne and reinterred them in his mother's grave at the Cimetière du Grand Jas in Cannes, France, reuniting them in their final resting place.

5. Personal Life and Family

Beyond his professional achievements, Fabergé's personal life was centered around his family, and his character was remembered through the detailed recollections of his associates.

5.1. Marriage and Children

Peter Carl Fabergé married Augusta Julia Jacobs on November 20, 1872. Together, they had five sons, four of whom lived to adulthood. Their children were:

- Eugène (Evgeny) Fabergé (1874-1960)

- Agathon Fabergé (1876-1951)

- Alexander Fabergé (1877-1952)

- Nicholas (Nikolai) Leopold Fabergé (1884-1939)

An earlier son, also named Nikolai, was born in 1881 but died in infancy in 1883.

5.2. Recollections and Character

Personal insights into Peter Carl Fabergé's character and working methods are preserved through the memoirs of those who knew him professionally. Henry Bainbridge who managed the London branch of the House of Fabergé, recorded his recollections of meetings with his employer in his autobiography, Twice Seven: The Autobiography of H C Bainbridge, and in his book dedicated to Fabergé, Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Imperial Court - His Life and Work. Further valuable insights come from François Birbaum, Fabergé's senior master craftsman from 1893 until the firm's demise. Birbaum's detailed account, The History of the House of Fabergé according to the recollections of the senior master craftsman of the firm Franz P. Birbaum, was handwritten in 1919 at the request of Soviet authorities and significantly expanded knowledge of the firm's operations.

Bainbridge described Fabergé as a man who preferred well-tailored tweed suits when he occasionally wore black, possessing the air of a country gentleman with large pockets that evoked a simple gamekeeper. He was a focused individual who disliked idle chatter and wasted actions. Bainbridge recounted an instance at dinner where Fabergé, upon hearing a long-winded story about a deceased lord, sharply retorted, "What is a dead banker to me?"

Fabergé was often in a hurry when taking orders from clients and would quickly forget details, prompting his staff to discreetly ascertain what he had heard. His great-granddaughter, Tatiana Fabergé, remembered him always carrying a handkerchief tied in his breast pocket. He was known for his wit and had little patience for pretense. Birbaum recalled that when Fabergé was displeased with a piece, he would summon the senior master craftsman and deliver a lengthy reprimand. On occasion, when Birbaum realized the design fault was Fabergé's own, he would show Fabergé his original sketch, to which Fabergé would smile guiltily and say, "No one scolds me, so I had to scold myself." He was also famous for his sharp wit, which he used unsparingly on pompous individuals. For example, when a dandy prince boasted about a recent honor from the Emperor, claiming not to know why he received it, Fabergé simply replied, "Indeed, Your Highness, I don't know either."

Fabergé famously traveled light, always arriving at his destination without luggage and purchasing all necessities upon arrival. Once, upon arriving at the Hôtel Negresco in Nice empty-handed, he was initially stopped by the doorman. Fortunately, a Grand Duke staying at the hotel greeted Fabergé loudly, leading to apologies and his admittance. Bainbridge concluded that Fabergé's defining characteristic was his generosity, which he believed was undoubtedly the foundation of his success.

6. Legacy and Lasting Impact

Peter Carl Fabergé's death did not diminish his artistic and cultural impact; instead, his creations have continued to be celebrated, influencing the art world and maintaining their status as symbols of luxury and historical significance.

6.1. Artistic and Cultural Legacy

According to Henry Bainbridge, when Fabergé took over the firm in 1872, it held "no special significance," though it was a sound business. However, over time, Fabergé elevated its artistry to a much higher level, establishing a foundation of lightness and elegance in design as he began creating objects of fantasy in addition to traditional jewelry. Fabergé's craftsmanship left an indelible mark on the art of jewelry making, and his creations continue to be highly sought after and admired globally.

The Imperial Easter Eggs, in particular, hold immense cultural significance, representing the pinnacle of Russian decorative arts and the opulence of the Romanov era. These masterpieces are now held in various prestigious collections worldwide, including the Kremlin Armoury Museum in Moscow, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Walters Art Museum, and the Royal Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

In the United States, Fabergé's work gained significant appreciation, notably through the collection of American businessman Malcolm Stevenson Forbes. In 2004, Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg, through his TNK oil business, acquired nine of these Imperial Easter Eggs from the Forbes collection for approximately 100.00 M USD. These eggs are now housed and displayed at the Fabergé Museum in the Shuvalev Palace in Saint Petersburg, which opened in 2013, bringing a significant portion of the collection back to Russia.

The Fabergé brand has also seen a modern revival. After various transitions, the trademark is now part of Gemfields, a leading supplier of responsibly sourced colored gemstones. This revival has been supported by Peter Carl Fabergé's direct descendants, including his great-granddaughters Tatiana Fabergé and Sarah Fabergé, ensuring that the legacy of exquisite craftsmanship continues into the 21st century with new collections of jewelry and watches.