1. Early Life and Education

Okakura's early life was marked by exposure to both traditional Japanese and Western influences, laying the groundwork for his future role as a cultural mediator. His education under significant mentors, particularly Ernest Fenollosa, profoundly shaped his artistic and philosophical views.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Okakura Kakuzō was born on February 14, 1863, in Honmachi 5-chome, Yokohama (near the present-day Yokohama Port Opening Memorial Hall). He was the second son of Okakura Kan'emon, a former low-ranking samurai of the Fukui Domain who transitioned into a silk merchant. His father, recognizing the burgeoning overseas trade in Yokohama, had opened a trading house called "Ishikawaya" in 1860, where Kakuzō was born. He was initially named "Kakuzō" (角蔵), meaning "corner warehouse," after the location of his birth, but later changed the spelling of his name to different Kanji meaning "awakened boy" (覚三).

His mother, Kono (née Nobata, 1834-1870), also from Fukui, was the second wife of Kan'emon. She was notably tall, standing at 65 in (165 cm). She gave birth to five children with Kan'emon: an elder son, Kōichirō (1861-1875), Kakuzō (Tenshin), a third son Genzo (who died young), a fourth son Yuzaburo (1868-1936), and a fifth daughter Chōko (1870-1943). Kono passed away from puerperal fever at the age of 37, shortly after Chōko's birth. Due to Kōichirō's care needs (he suffered from spinal caries), Kakuzō was raised by a wet nurse who was a distant relative of Hashimoto Sanai. After Kono's death, Kan'emon married a third wife, Shizu Ōno, but they had no children.

1.2. Education and Mentors

Okakura's education began with exposure to English at a school operated by the Christian missionary Dr. James Curtis Hepburn, known for the Hepburn romanization system. Here, he became proficient in English but initially struggled with Kanji. To balance this, his father arranged for him to concurrently study traditional Japanese culture at a Buddhist temple, Chōenji, where he learned Han (Chinese classics). He also attended a Western-style school opened by Takashima Kaemon.

In 1871, following the abolition of the feudal system and the closure of Ishikawaya, his family moved to Tokyo. In 1873, Okakura entered the Tokyo Institute of Foreign Languages (now Tokyo University of Foreign Studies). In 1875, he enrolled in the Tokyo Kaisei School (which later became Tokyo Imperial University in 1877), where he studied political science and economics. His proficiency in English led him to become an assistant to Ernest Fenollosa, a Harvard-educated art historian who taught at the university. This intellectual relationship with Fenollosa was pivotal, as Okakura assisted him in collecting Japanese art and was deeply influenced by Fenollosa's insights into Japanese aesthetics. At the age of 16, Okakura married Kiko, a descendant of Ōoka Tadasuke, whom he met at a tea house. In 1882, he became an instructor at Senshu School, contributing significantly to its early success and inspiring students, including Keiichi Ura, who was profoundly influenced by Okakura's guidance.

2. Career and Activities

Okakura's career was marked by his profound impact on art education, his pioneering role in establishing key art institutions, and his extensive international cultural diplomacy. He dedicated his life to fostering cross-cultural understanding and preserving Japanese artistic heritage.

2.1. Art Education and Institutional Founding

In 1886, Okakura was appointed secretary to the Minister of Education and was put in charge of musical affairs. Later that year, he was named to the Imperial Art Commission and dispatched abroad to study fine arts in the Western world. Upon his return from Europe and the United States in 1887, he played a crucial role in the founding of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (東京美術学校, Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō), becoming its director a year later. Although Hamao Arata served as acting principal, Okakura was the de facto first principal, with Fenollosa as vice-principal. The school, established in 1889, aimed to counteract both the "lifeless conservatism" of traditionalists and the "equally uninspired imitation of Western art" prevalent in early Meiji Japan.

Under his leadership, the Tokyo School of Fine Arts became a nurturing ground for many future masters of Japanese art, including Yokoyama Taikan, Shimomura Kanzan, Hishida Shunsō, Fukuda Bisen, and Saigō Kogetsu. Okakura's lectures on Japanese art history from 1890 to 1893 at the school are considered the first comprehensive historical narrative of Japanese art by a Japanese scholar.

In 1897, when it became apparent that European methods were to be given increasing prominence in the school's curriculum, Okakura resigned his directorship. Six months later, he renewed his efforts to integrate Western artistic principles without compromising national inspiration by co-founding the Nihon Bijutsuin (日本美術院, lit. "Japan Visual Arts Academy") in Yanaka, Shitaya-ku, with Hashimoto Gahō, Yokoyama Taikan, and thirty-seven other leading artists.

2.2. Preservation and Promotion of Japanese Art

Okakura was a staunch advocate for the revival and promotion of traditional Japanese arts. He actively sought to rehabilitate ancient and native art forms, honoring their ideals and exploring their contemporary possibilities, particularly through the new periodical Kokka. He stood against the uncritical adoption of Western styles, viewing them as a threat to Japan's unique cultural identity. His efforts were instrumental in establishing Nihonga, or painting done with traditional Japanese techniques, as a vital cultural heritage in the face of the emerging Western-style painting, Yōga.

He also opposed the Haibutsu kishaku movement, a Shintoist movement that sought to expel Buddhism from Japan in the wake of the Meiji Restoration. Working alongside Ernest Fenollosa, Okakura dedicated himself to repairing damaged Buddhist temples, images, and texts, further cementing his commitment to preserving Japan's diverse cultural and artistic legacy.

2.3. International Activities and Exchange

Okakura was a cosmopolitan figure who maintained an international outlook. He notably wrote all of his major works in English, aiming to communicate Japanese and Asian cultural values to a global audience. He traveled extensively, researching Japan's traditional art and visiting Europe, the United States, and China. He lived for two years in India (1901-1902), where he engaged in significant dialogues with prominent figures such as Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore.

Through these interactions and his writings, Okakura emphasized the importance of Asian culture to the modern world, striving to introduce its influence into realms of art and literature that were largely dominated by Western culture at the time. His travels and intellectual exchanges were central to his mission of fostering cross-cultural understanding and challenging Western cultural hegemony.

2.4. Role at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In 1904, Okakura was invited by William Sturgis Bigelow, an American collector of Japanese art, to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). He began working with the museum, traveling frequently between Japan and Boston to acquire and organize its collections. In 1910, with the support of Edward Jackson "Ned" Holmes, the MFA's director and a Japanese art enthusiast whose wife was Japanese, Okakura was appointed Curator of its Department of Japanese and Chinese Art. Prior to this appointment, he also undertook a survey of Asian art departments in European museums.

In this role, he played a crucial part in organizing and expanding the museum's significant collection of Asian art, as well as introducing Asian art and aesthetics to the Western public. His presence at the MFA contributed significantly to the understanding and appreciation of East Asian art in the Western world. Among his American students at the museum was Langdon Warner.

3. Thought and Writings

Okakura's philosophical ideas were deeply rooted in his critical analysis of East-West relations and his profound appreciation for Asian cultural values. His major literary works served as powerful expressions of his thought, advocating for a re-evaluation of Eastern traditions in a rapidly Westernizing world.

3.1. Major Works

Okakura's significant books contributed substantially to art criticism and cultural philosophy, articulating his vision for Asian identity and its interaction with the West.

3.1.1. The Ideals of the East

Published in London in 1903, on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War, The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japan is renowned for its opening paragraph, which asserts a spiritual unity across Asia, distinguishing it from the West. Okakura wrote:

:Asia is one. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilisations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas. But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love for the Ultimate and Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the great religions of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of the Mediterranean and the Baltic, who love to dwell on the Particular, and to search out the means, not the end, of life.

This work laid a foundational stone for Pan-Asianist thought, emphasizing a shared spiritual and philosophical heritage that transcended geographical and cultural differences within Asia.

3.1.2. The Awakening of Japan

In his subsequent book, The Awakening of Japan, published in 1904, Okakura reflected on Japan's rapid modernization and its implications for Asia. He famously argued that "the glory of the West is the humiliation of Asia," an early expression of his Pan-Asianist views. He also noted that Japan's swift adoption of Western ways was not universally welcomed by its Asian neighbors, stating, "We have become so eager to identify ourselves with European civilization instead of Asiatic that our continental neighbors regard us as renegades-nay, even as an embodiment of the White Disaster itself." This work highlighted his concerns about the uncritical embrace of Western values and its potential to alienate Japan from its Asian roots.

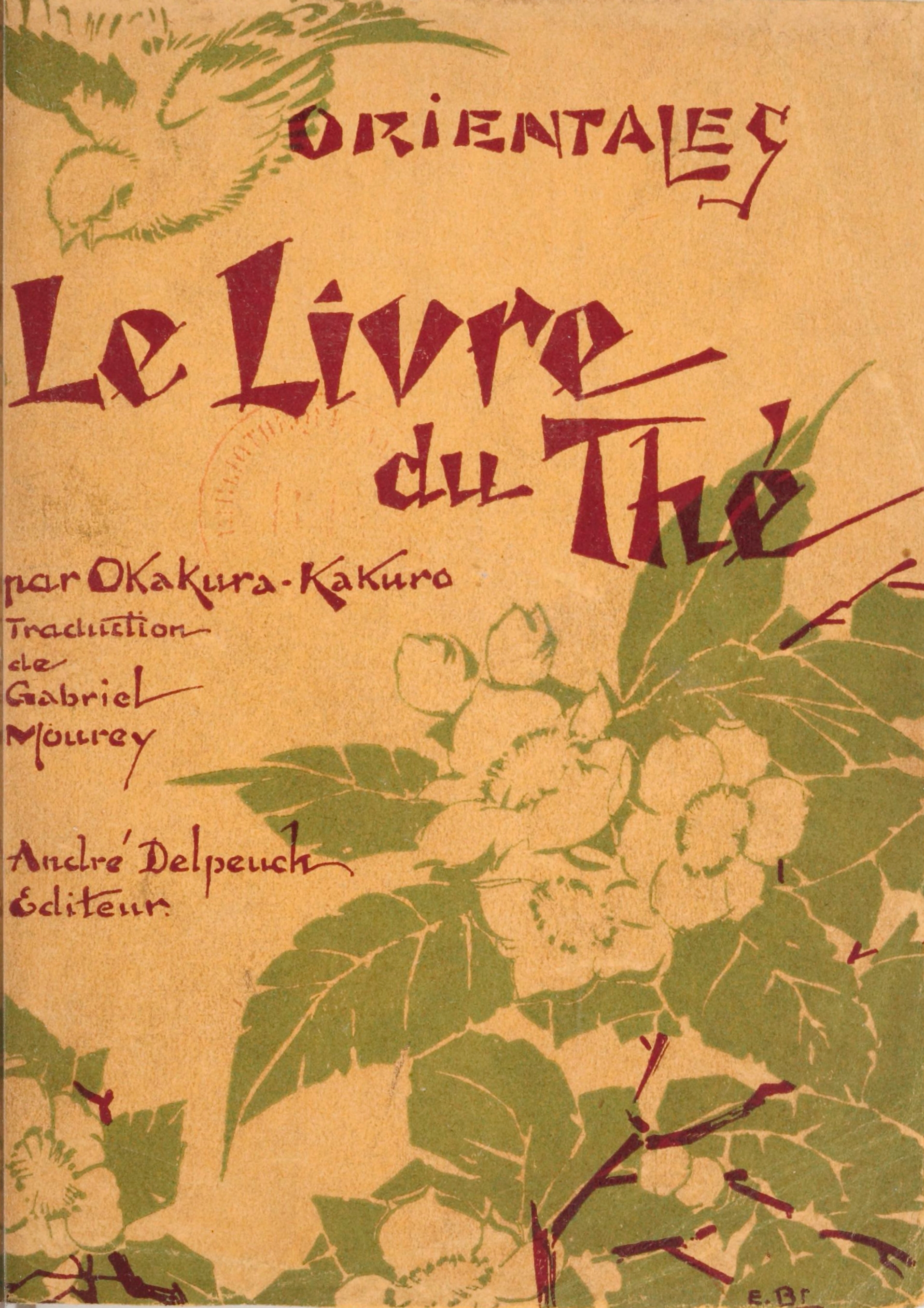

3.1.3. The Book of Tea

The Book of Tea, written and published in 1906, is considered "the earliest lucid English-language account of Zen Buddhism and its relation to the arts." In this work, Okakura argued that "Tea is more than an idealization of the form of drinking; it is a religion of the art of life." He described "Teaism" as a philosophy that

:It insulates purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order. It is essentially a worship of the Imperfect, as it is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.

Okakura used the tea ceremony as a lens through which to critique Western perceptions of the East. He suggested that Westerners, in their "sleek complacency," viewed the tea ceremony as "but another instance of the thousand and one oddities which constitute the quaintness and childishness of the East to him." Writing in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War, he poignantly observed that Westerners regarded Japan as "barbarous while she indulged in the gentle arts of peace," and began to call her civilized only when "she began to commit wholesale slaughter on the Manchurian battlefields." This work served as both an aesthetic treatise and a cultural critique, advocating for a deeper understanding of Eastern spirituality and artistic principles.

The enduring influence of The Book of Tea is evident in its numerous translations into various languages, including French and Esperanto, making Okakura's philosophical insights accessible to a broader international audience.

3.1.4. The White Fox

Okakura's final work, The White Fox, was an English-language libretto written in 1912 under the patronage of Isabella Stewart Gardner for the Boston Opera House. The libretto draws elements from both Kabuki plays and Richard Wagner's epic opera Tannhäuser. This blend of Eastern and Western artistic forms can be interpreted metaphorically as an expression of Okakura's hope for reconciliation and harmony between Eastern and Western cultural ideals. Although Charles Martin Loeffler agreed to set the poetic drama to music, the project was never fully completed or staged, leading to a strained relationship between Okakura and Loeffler.

3.2. Philosophy and Thought

Okakura's broader philosophical stance centered on the assertion and preservation of Asian cultural values, which he believed offered a vital counterpoint to the perceived excesses of Western civilization. He was a vocal critic of Western materialism and militarism, arguing that the West's focus on the "particular" and the "means, not the end, of life" led to a spiritual emptiness and destructive tendencies.

His concept of "Teaism," as articulated in The Book of Tea, was not merely about the tea ceremony itself but represented a profound philosophy of life rooted in harmony, purity, respect, and tranquility. He saw the tea ceremony as an embodiment of the "religion of the art of life," a path to appreciating beauty in imperfection and finding spiritual solace amidst the complexities of existence. Through his writings, Okakura sought to elevate Eastern aesthetics and spirituality, presenting them as universal values capable of enriching global culture and fostering a more balanced understanding between East and West.

4. Personal Life

Okakura's personal life, though less publicly documented than his professional achievements, provides insight into his family relationships and the challenges he faced.

4.1. Family Relations

Okakura Kakuzō married Kiko (also spelled Moto or Shige) in 1879. Kiko, born in 1865, was the daughter of Ōoka Sadao. Their marital life experienced difficulties, including a period of separation when Okakura became involved with Hatsuko Kuki, the wife of his patron, Baron Kuki Ryūichi. Hatsuko later separated from Ryūichi and gave birth to Shūzō Kuki, a philosopher who, as a child, sometimes believed Okakura to be his father. Kiko, along with wives of other prominent figures like Kenzō Takahashi, established a women's group called "Seiyūkai," dedicated to studying Japanese traditional womanhood, adopting an Ōoku-style appearance for their outings.

Okakura and Kiko had two children: their eldest son, Kazuo (1881-1943), who became a journalist and later compiled a biography of his father; and their eldest daughter, Komako (1883-1955). Komako attended Futsu Eiwa Koto Jogakko (now Shirayuri Gakuen Junior High School and High School) and married Tatsuo Yoneyama, who worked for the Ministry of Railways. She accompanied her husband as he was transferred to various locations as a railway bureau chief and eventually passed away in Izura, where she had retired.

Okakura also had an illegitimate son, Saburo (1895-1937), with Yasugi Sada (1869-1915), who was Hatsuko Kuki's half-sister. Sada attempted suicide the year after Saburo's birth. Saburo was initially placed with another family, then adopted by Masayasu Wada at age five. After Wada's death in 1902, Saburo was taken in by his mother, who had married Kōkichi Hayasaki. From middle school onwards, he was entrusted to Chushiro Kenmochi (both Wada, Hayasaki, and Kenmochi were Okakura's subordinates). Saburo went on to study at the Eighth Higher School in Nagoya and then the Tokyo Imperial University Faculty of Medicine, becoming a psychiatrist. He worked at Matsuzawa Hospital in Tokyo and later became an assistant professor at Kumamoto Medical University and director of the Yōshinkan Hospital in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Okakura's descendants include his grandson, Koshirō Okakura (Kazuo's son), an international political scholar involved in the Non-Aligned Movement. His great-grandson, Tetsushi Okakura (Koshirō's eldest son), is a Middle East scholar, and another great-grandson, Takashi Okakura, is a Western/African history scholar. His great-great-grandson, Tadashi Okakura (Tetsushi's eldest son), is a photographer, and his great-great-grandson, Hiroshi Okakura (Tetsushi's second son), is a human resources consultant.

5. Death

Okakura Kakuzō's health began to deteriorate in his later years. In June 1913, he wrote to a friend, stating, "My ailment the doctors say is the usual complaint of the twentieth century-Bright's disease. I have eaten things in various parts of the globe-too varied for the hereditary notions of my stomach and kidneys. However, I am getting well again and I am thinking of going to China in September."

Despite his hopes for recovery, Okakura's condition worsened. In August 1913, he insisted on traveling to his mountain villa in Akakura, Myōkōkōgen, accompanied by his wife, daughter, and sister. For about a week, he felt slightly better and was able to converse. However, on August 25, he suffered a heart attack and endured several days of intense pain. Surrounded by his family, relatives, and disciples, Okakura passed away on September 2, 1913, at the age of 50. His death was attributed to chronic nephritis complicated by uremia. On the same day, he was posthumously awarded the Junior Fourth Rank and the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Fifth Class. His Buddhist posthumous name is Shakutenshin. Okakura's main grave is located in Somei Cemetery in Komagome, Tokyo, and a portion of his ashes were also interred in a grave in Izura, as per his will.

6. Legacy and Influence

Okakura Kakuzō's legacy is complex and far-reaching, encompassing his pivotal role in Japanese art, his international cultural discourse, and the controversies surrounding his nationalist sentiments.

6.1. Role in the Japanese Art Scene

In Japan, Okakura is widely credited, along with Ernest Fenollosa, for "saving" Nihonga, or painting done with traditional Japanese techniques. At the time, Nihonga was perceived to be under threat of replacement by Western-style painting, known as Yōga, which was primarily championed by artists like Seiki Kuroda. While contemporary art scholars debate the extent to which oil painting posed a serious "threat" to traditional Japanese painting, and thus the literal "saving" role of Okakura, there is broad consensus that he was instrumental in modernizing Japanese aesthetics. He recognized the crucial need to preserve Japan's cultural heritage during the rapid modernization of the Meiji Restoration, making him one of the period's major reformers in the arts. His efforts helped shape the course of modern Japanese art history and ensured the continued vitality of traditional artistic forms.

6.2. International Influence

Beyond Japan, Okakura Kakuzō exerted a significant influence on a number of important figures, both directly and indirectly. He was a close personal friend of the American art benefactor, collector, and museum founder Isabella Stewart Gardner, who supported his work and intellectual pursuits. His ideas resonated with prominent intellectuals and artists, including the philosopher Martin Heidegger, the poet Ezra Pound, and especially the renowned Indian poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore, with whom he engaged in deep intellectual exchanges during his time in India.

Okakura was also part of a trio of Japanese artists who introduced the wash technique to Abanindranath Tagore, who is considered the father of modern Indian watercolor painting. His efforts to introduce Asian culture and aesthetics to the Western world, particularly through his English writings, contributed to a broader appreciation of Eastern art and philosophy in the early 20th century, influencing various cultural and artistic movements.

6.3. Criticisms and Controversies

Okakura Kakuzō's legacy is not without its criticisms and controversies. While he is celebrated for his contributions to art preservation and cultural exchange, his Pan-Asianist ideas have been subject to scrutiny. His assertion of "Asia is one" in The Ideals of the East and his critique of Western militarism in The Book of Tea were part of a broader argument for Asian solidarity against Western dominance. However, some scholars and critics view his Pan-Asianism as having nationalist undertones that could be interpreted as supportive of Japanese imperial ambitions. For instance, in Korea, he is regarded by some as a "right-wing ideologue" and a proponent of Jeonghanron (정한론), an argument for the conquest of Korea, which aligns with the critical perspective on his political stances.

Furthermore, his personal life was marked by controversy, notably the "Art School Incident" (美術学校騒動, Bijutsu Gakkō Sōdō), which involved his romantic relationship with Hatsuko Kuki, the wife of his superior, Baron Kuki Ryūichi. This affair was rumored to have contributed to his forced resignation from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1898. These aspects present a more complex and balanced view of his legacy, acknowledging both his significant cultural contributions and the contentious elements of his thought and actions.

7. Commemorative Projects

Numerous institutions and initiatives have been established to honor Okakura Kakuzō's life and work, reflecting his lasting impact on Japanese and international culture.

In 1931, a statue of Okakura Tenshin, sculpted by Hirakushi Denchū, was unveiled in the front garden of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now part of Tokyo University of the Arts).

In 1942, the Tenshin Ō Shōzōhi (天心翁肖像碑), a monument featuring a portrait of Okakura and inscribed with "Asia is One," was completed in Izura, on the Goura Coast in Kitaibaraki, Ibaraki Prefecture, where he spent his later years. A dedication ceremony was held on November 8 of that year, attended by artists such as Yokoyama Taikan, Saitō Ryūzō, and Ishii Tsuruzō.

In 1967, the Okakura Tenshin Memorial Park was opened in Taitō Ward, Tokyo, on the former site of his residence and the Nihon Bijutsuin.

In 1997, the Ibaraki Prefectural Tenshin Memorial Izura Art Museum was established in Kitaibaraki City, Izura, to commemorate the achievements of Okakura and other artists who relocated the first section of the Nihon Bijutsuin there.

In 2006, on October 9, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the publication of The Book of Tea in New York, a symposium was held at Eihei-ji Temple in Fukui Prefecture, a place Okakura deeply cherished. In 2013, to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth and 100th anniversary of his death, the Fukui Prefectural Museum of Art hosted a special exhibition titled "The Unprecedented Okakura Tenshin Exhibition."

Rokkakudō, an hexagonal wooden retreat designed by Okakura and built in 1905, overlooking the sea along the Izura coast in Kitaibaraki, Ibaraki Prefecture, is managed by the Izura Institute of Arts & Culture, Ibaraki University. It is registered as a national monument.