1. Overview

Hishida Shunso (菱田 春草Hishida ShunsōJapanese, September 21, 1874 - September 16, 1911) was a prominent Japanese painter during the Meiji period, recognized for his pivotal role in the innovation and modernization of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting). A disciple of Okakura Tenshin, alongside contemporaries like Yokoyama Taikan and Shimomura Kanzan, Hishida challenged traditional artistic conventions. He is particularly known for developing the "moro-tai" (vague style), an experimental technique that eliminated traditional outlines in favor of color gradation to achieve atmospheric effects. Although initially met with criticism, this innovative approach, later integrated with traditional line drawing, significantly influenced the evolution of modern Nihonga. His artistic journey included extensive travels to India, the United States, and Europe, where he exhibited his works and engaged in cultural exchange. His contributions, though cut short by his early death, left a lasting impact on Japanese art, pushing the boundaries of expression and contributing to a dynamic period of cultural evolution. His real name was Hishida Miyoji (三男治MiyojiJapanese).

2. Biography

2.1. Early Life and Family Background

Hishida Shunso was born on September 21, 1874, in what is now part of Iida city in Nagano Prefecture. He was the third son of Hishida Enji, a former samurai of the Shinano Iida Domain. His early education took place at Iida School, which is now the Otemachi Elementary School.

2.2. Education and Artistic Training

In 1889, Shunso moved to Tokyo to pursue his artistic studies, initially learning under Kanō school artist Yuki Masaaki (1834-1904) at his private art juku. The following year, in 1890, he enrolled in the Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō (東京美術学校Tōkyō Bijutsu GakkōJapanese, the predecessor to the Tokyo University of the Arts). At the school, Shunso was one year junior to his notable colleagues Yokoyama Taikan and Shimomura Kanzan. His primary teacher at the school was Hashimoto Gahō, a descendant of the Kano school. During their time at Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō, Shunso, Taikan, and Kanzan were profoundly influenced by the school's director, Okakura Tenshin (Kakuzo), and Ernest Fenollosa. The curriculum also included lectures by Fenollosa on aesthetics, Okakura Tenshin on Japanese art history, and Kurokawa Mayori, a teacher of both Fenollosa and Okakura, on historical court practices (yusoku kojitsu), Japanese literature, metalwork, and lacquer history.

2.3. Career Development and Nihon Bijutsuin

Upon graduating in 1895 at the age of 21, Shunso was commissioned by the Imperial Household Museum (now the Tokyo National Museum) to undertake a significant project copying ancient religious paintings at Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Nara from the autumn of that year through the following year. He also served as a teacher at the Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō.

In 1898, a controversy led to Okakura Tenshin's resignation as director of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, reportedly due to opposition from conservative factions. In solidarity, Shunso, Taikan, and Kanzan, who were then teachers at the school, also left. They joined Okakura Tenshin in establishing the Nihon Bijutsuin (日本美術院Nihon BijutsuinJapanese), an independent art organization. In 1906, Shunso relocated to Izura (五浦IzuraJapanese) in Kitaibaraki City, Ibaraki Prefecture, where the Nihon Bijutsuin had moved its institute. There, he dedicated himself to his artistic endeavors alongside Taikan and Kanzan.

2.4. Overseas Travels

Hishida Shunso undertook significant international travels that broadened his artistic perspective. In 1903, he traveled to India with Yokoyama Taikan. The following year, in 1904, he journeyed to the United States with Okakura Tenshin and Taikan, continuing on to Europe before returning to Japan in 1905. During these travels, he held exhibitions of his works, contributing to cultural exchange and exposing his art to international audiences.

3. Artistic Career and Style

3.1. Influences and Artistic Environment

Hishida Shunso's artistic development was deeply shaped by his mentors and the dynamic artistic environment of the Meiji era. His primary influences included Okakura Tenshin, the visionary director of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and Ernest Fenollosa, an American philosopher and art historian who championed traditional Japanese art while advocating for its modernization. These figures encouraged artists to move beyond rigid traditional styles and explore new forms of expression. Shunso also studied under Hashimoto Gahō, a master of the Kano school, who provided him with a strong foundation in classical Japanese painting techniques. The broader artistic milieu of the Meiji period, characterized by a blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and influences from Western art, provided a fertile ground for his experimental approaches.

3.2. Development of 'Moro-tai' Style

Around 1900, Shunso, along with Yokoyama Taikan, began experimenting with a revolutionary painting method that challenged the fundamental principles of traditional Japanese painting. This new technique abandoned the use of outlines, which had been indispensable in Japanese art, in favor of a gradation of colors to define forms and create atmospheric effects. This experimental style was derisively named moro-tai (朦朧体mōrōtaiJapanese, meaning "vague style") by contemporary critics, who severely criticized its departure from established norms. Works such as Chrysanthemum Boy and Autumn Landscape (Keizan Koyo) are considered typical examples of this "moro-tai" style.

Shunso eventually recognized that while moro-tai was effective in depicting scenes with atmospheric qualities, such as morning mist or evening glow, its color gradation technique proved limited to specific motifs. To overcome this disadvantage, he began integrating his original moro-tai approach with traditional line drawing techniques after his return to Japan in 1905, also incorporating elements reminiscent of the Rinpa school. His later works exhibit a refined style that came to typify the Nihonga genre, distinguishing it from the more restrictive styles of traditional Japanese painting and achieving a rational spatial expression within the world of Japanese painting through techniques like aerial perspective.

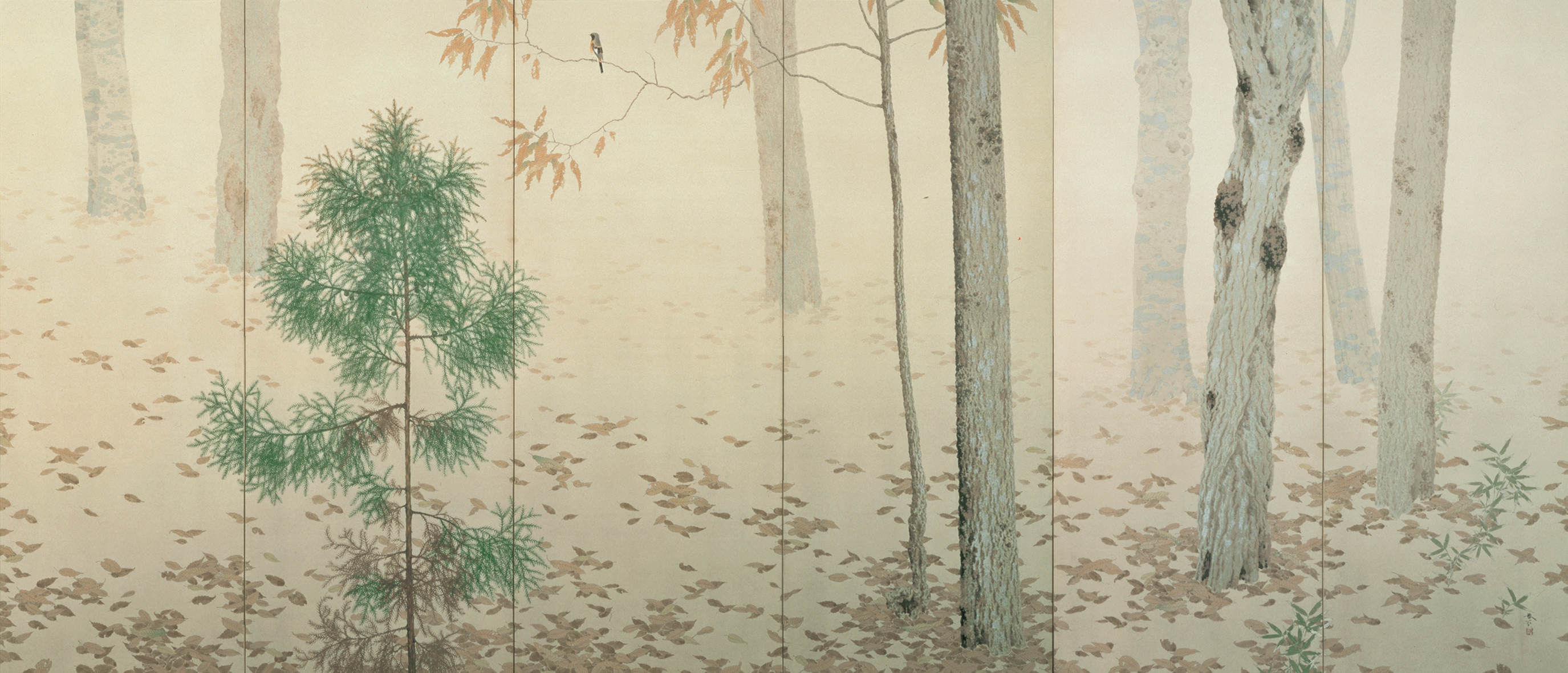

3.3. Participation in National Exhibitions

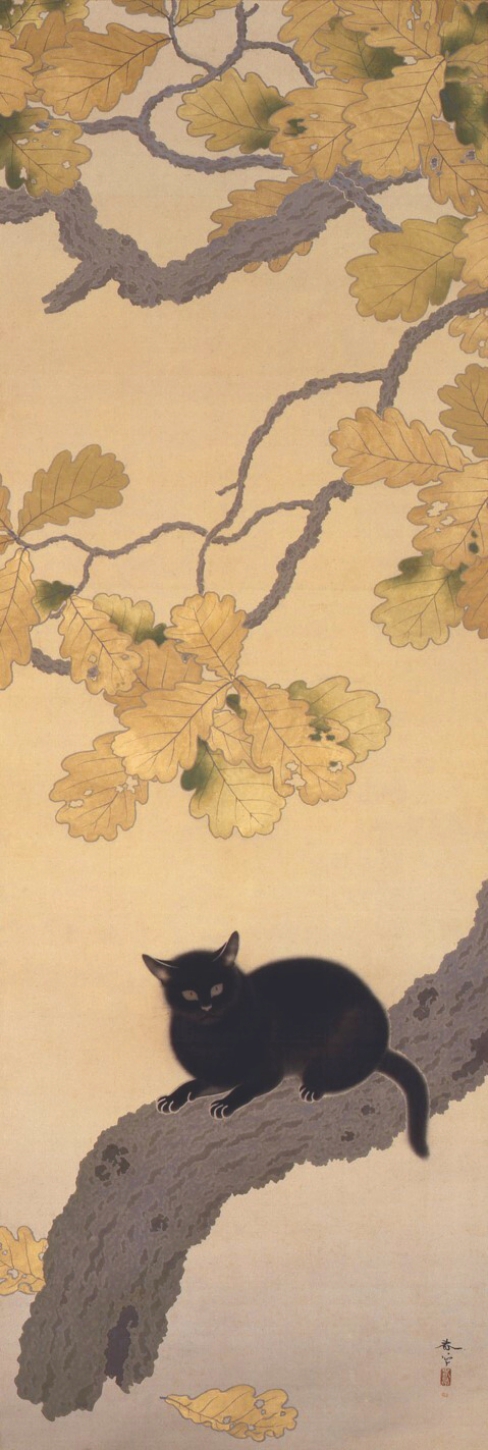

After his return to Japan, Shunso became a prominent participant in various national art exhibitions, notably the government-sponsored Bunten (文展BuntenJapanese, Ministry of Education Art Exhibition). In 1907, he exhibited Bodhisattva Kenshu at the first Bunten exhibition, where it received favorable reviews, marking his emergence as a leading artist on this new official platform. He continued to be a significant presence at the Bunten exhibitions. In 1909, his work Ochiba (落葉Fallen LeavesJapanese) received the highest award at the third Bunten Exhibition. This painting, which depicts a thicket of trees around Yoyogi, Tokyo (then a suburb), is now designated an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government's Agency for Cultural Affairs and is part of the collection of the Eisei Bunko Museum in Tokyo. His 1910 work Black Cat (黒き猫) has also been designated an Important Cultural Property.

4. Major Works

Hishida Shunso created a significant body of work throughout his career, many of which are designated as Important Cultural Properties. His works often explored themes of nature, classical literature, and Buddhist figures, while showcasing his innovative techniques.

- Widow and Orphan (寡婦と孤児, 1895, Tokyo University of the Arts) - His graduation work, highly rated. It is likely based on the "Rebellion of Kitayama-dono" from Volume 13 of Taiheiki.

- Reflection in the Water (水鏡, 1897, Tokyo University of the Arts)

- Six Immortal Poets (六歌仙, 1899, Eisei Bunko, entrusted to Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art)

- Autumn Landscape (秋景 渓山紅葉, 1899, Shimane Art Museum)

- Chrysanthemum Boy (菊慈童, 1900, Iida City Museum)

- Moon after The Snow (雪後の月, 1902, Shiga Museum of Art)

- Wong Zhaojun (王昭君, 1902, Zenpo-ji Temple, entrusted to National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Important Cultural Property)

- Cat and Plum Blossoms (猫梅, 1906, Adachi Museum of Art)

- Bodhisattva Kenshu (賢首菩薩, 1907, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Important Cultural Property)

- Fallen Leaves (落葉, 1909, Eisei Bunko, entrusted to Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art, Important Cultural Property) - A masterpiece that achieved rational spatial expression in Japanese painting using aerial perspective, while employing traditional screen format.

- Black Cat (黒き猫, 1910, Eisei Bunko, entrusted to Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art, Important Cultural Property) - His last work exhibited at the Bunten. It was completed in just five days after an initial attempt at a different subject was abandoned. The model cat was borrowed from a local baked sweet potato vendor.

The following table provides a more detailed list of his works:

| Work Name | Technique | Owner | Date | Cultural Property Designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn Landscape (秋景山水) | Color on paper | Tokyo University of the Arts Museum | 1893 | |

| Kamukura Period Bullfighting Scene (鎌倉時代闘牛の図) | Color on silk | Private | 1894 | |

| Widow and Orphan (寡婦と孤児) | Color on silk | Tokyo University of the Arts Museum | 1895 | |

| Koyasan Landscape (高野山風景) | Color on silk | Kinoshita Museum | 1895 | |

| Four Seasons Landscape (四季山水) | Color on paper | Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art | 1896 | |

| Nengetsu Bishō (拈華微笑) | Color on silk | Tokyo National Museum | 1897 | |

| Reflection in the Water (水鏡) | Color on silk | Tokyo University of the Arts Museum | 1897 | |

| Musashino (武蔵野) | Color on silk | Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art | 1898 | |

| Cold Forest (寒林) | Ink on paper | Reiyukai Myoichi Memorial Hall | 1898 | |

| Fox under the Moon (月下狐) | Color on paper | Mizuno Museum of Art | 1899 | |

| Six Immortal Poets (六歌仙) | Color on gold paper | Eisei Bunko (entrusted to Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art) | 1899 | |

| Autumn Landscape (Keizan Koyo) (秋景(渓山紅葉)) | Color on silk | Shimane Art Museum | 1899 | |

| Autumn Field (秋野) | Color on silk | Toyama Memorial Museum | 1899 | |

| Inada Hime (稲田姫) | Color on silk | Mizuno Museum of Art | 1899 | |

| Chrysanthemum Boy (菊慈童) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1900 | |

| Fushihime (Tokiwazu) (伏姫(常磐津)) | Color on silk | Nagano Prefectural Shinano Art Museum | 1900 | |

| Fishing Boat on the Lake (湖上釣舟) | Ink and light color on paper | Saitama Prefectural Museum of Modern Art | 1900 | |

| Return from Fishing (釣帰) | Color on silk | Yamatane Museum of Art | 1901 | |

| Su Li Farewell (蘇李訣別) | Color on silk | Private | 1901 | |

| Dusk (暮色) | Color on silk | Kyoto National Museum | 1901 | |

| Azalea and Doves (Onrei) (躑躅双鳩(温麗)) | Color on silk | Fukui Prefectural Museum of Art | 1901 | |

| Waterfall (Ryūdō) (瀑布(流動)) | Color on silk | Hikari Museum | 1901 | |

| Rafusen (羅浮仙) | Color on silk | Nagano Prefectural Shinano Art Museum | 1901 | |

| Moonlit Night Flying Heron (Rikuri) (月夜飛鷺(陸離)) | Color on silk | Hayashibara Museum of Art | 1901 | |

| Noble Man Gazing at Mountains (Sōchō) (高士望岳(荘重)) | Ink on silk | Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum | 1902 | |

| Coastline Rough Waves (Yūkai) (海岸怒涛(雄快)) | Color on silk | Nagano Prefectural Shinano Art Museum | 1902 | |

| Wang Zhaojun (王昭君) | Color on silk | Zenpo-ji Temple (entrusted to Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art) | 1902 | Important Cultural Property |

| Reishōjo (霊昭女) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1902 | Iida City Tangible Cultural Property |

| Autumn Grasses (秋草) | Color on paper | Mizuno Museum of Art | 1902 | |

| Moon After Snow (雪後の月) | Color on silk | Shiga Prefectural Museum of Modern Art | 1902 | |

| Benzaiten (弁財天) | Color on silk | Private | 1903 | From his period in India |

| Deer (鹿) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1903 | Iida City Tangible Cultural Property |

| Setting Sun (夕陽) | Color on silk | Private | 1903 | |

| Rain (Mountain Path) (雨(山路)) | Color on silk | Hasegawa Machiko Art Museum | 1903 | Originally part of a pair "Wind and Rain" |

| White Drawing under Plum Blossoms (梅下白描) | Color on silk | Fukuda Art Museum | c. 1903 | |

| Spring Garden (春庭) | Color on silk | Fukuda Art Museum | c. 1897-1906 | |

| Night Cherry Blossoms (夜桜) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1904 | Iida City Tangible Cultural Property |

| Evening Forest (夕の森) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1904 | Iida City Tangible Cultural Property |

| Returning Woodcutter (帰樵) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1906 | Iida City Tangible Cultural Property |

| Bodhisattva Kenshu (賢首菩薩) | Color on silk | National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo | 1907 | Important Cultural Property |

| Mount Horai (蓬莱山) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | Early 20th century | |

| Thistle and Dove (薊に鳩) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | Early 20th century | |

| Jellyfish (海月) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | c. 1907 | |

| Brilliant Morning Light (旭光耀々) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | c. 1907 | |

| Moon Between Pines (松間の月) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | Early 20th century | |

| Waterfall (瀑布の図) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | Early 20th century | |

| Lin Hejing (林和靖) | Color on silk | Ibaraki Museum of Modern Art | 1908 | |

| Small Birds on Paulownia (桐に小禽) | Color on silk | Mizuno Museum of Art | 1908 | |

| Autumn Leaves Landscape (紅葉山水) | Color on silk | Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art | 1908 | Formerly owned by patron Akimoto Shatei |

| Autumn Trees (秋木立) | Color on silk | National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo | 1909 | |

| Fallen Leaves (落葉) | Color on silk | Shiga Prefectural Museum of Modern Art | 1909 | Considered the first in a series of "Fallen Leaves" works |

| Fallen Leaves (Unfinished) (落葉(未完)) | Color on paper | Private | 1909 | |

| Fallen Leaves (落葉) | Color on paper | Eisei Bunko (entrusted to Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art) | 1909 | Important Cultural Property |

| Fallen Leaves (落葉) | Color on silk | Ibaraki Museum of Modern Art | 1909 | |

| Fallen Leaves (落葉) | Color on paper | Fukui Prefectural Museum of Art | 1909 | |

| Ascetic Practice (苦行) | Color on silk | Himeji City Museum of Art | 1909 | |

| Deer in Snow (雪中の鹿) | Color on silk | Yoshino Gypsum Co., Ltd. | c. 1909 | |

| Dawn Sea (暁の海) | Color on silk | Yoshino Gypsum Co., Ltd. | Undated | |

| Four Seasons Landscape (四季山水) | Color on silk | National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo | 1910 | |

| Sparrows and Crows (雀に鴉) | Color on paper | National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo | 1910 | |

| Immortal Maiden (Reishōjo) (仙女(霊昭女)) | Color on silk | Private | 1910 | Commissioned by Uemura Shōen |

| Black Cat (黒き猫) | Color on paper | Reiyukai Myoichi Memorial Hall | 1910 | |

| Black Cat (黒き猫) | Color on silk | Eisei Bunko (entrusted to Kumamoto Prefectural Museum of Art) | 1910 | Important Cultural Property |

| Spring and Autumn (春秋) | Color on silk | Iida City Museum | 1910 | Iida City Tangible Cultural Property |

| Cat and Crow (猫に烏) | Color on gold paper | Ibaraki Museum of Modern Art | 1910 | |

| Small Birds on Autumn Leaves (紅葉に小禽) | Color on silk | Okada Museum of Art | c. 1910 | |

| Pine, Bamboo, Plum (松竹梅図) | Color on silver paper | Private | c. 1910 | |

| Pine and Bamboo (松と竹) | Ink and light color on silver paper | Private | Undated | |

| Early Spring (早春) | Color on silk | Private | 1911 | |

| Sparrow on Plum Blossoms (梅に雀) | Color on silk | National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo | 1911 | His last scroll painting, completed despite illness |

5. Personal Life

Hishida Shunso's wife, Chiyo, was the daughter of Nogami Muneo, a former Chōshū Domain samurai and a Second Lieutenant in the Army Transport Corps. After her father's early death in 1889, Chiyo was taken in by her mother's family, the Ishida family of the Iida Domain, which led to her meeting Shunso.

Shunso had notable siblings. His elder brother, Hishida Tamekichi (菱田為吉Hishida TamekichiJapanese), was a professor at the Tokyo Butsuri Gakko (now Tokyo University of Science), and polyhedral models he created are preserved at the Tokyo University of Science Museum of Modern Science. His younger brother, Hishida Yuizo (菱田唯蔵Hishida YuizoJapanese), became a professor at both Kyushu Imperial University and Tokyo Imperial University. Shunso's eldest son, Hishida Haruo (菱田春夫Hishida HaruoJapanese), later became a distinguished art appraiser.

6. Death

In his final years, Hishida Shunso suffered from severe kidney disease, specifically nephritis, which also affected his eyesight, leading to retinitis. Driven by a fear of blindness, he painted frantically during periods when his illness was in remission. Despite his deteriorating health, he continued to produce significant works, including Ochiba (Fallen Leaves), which won the highest award at the third Bunten Exhibition in 1909. Hishida Shunso died of kidney disease on September 16, 1911, just five days before his 37th birthday. His early death was deeply mourned by his mentors and peers, including Okakura Tenshin and Yokoyama Taikan.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

7.1. Impact on Modern Nihonga

Hishida Shunso's artistic innovations had a profound and lasting impact on the development and modernization of Japanese-style painting, or Nihonga. His experimental approach, particularly the development of the moro-tai (vague style) which eliminated traditional outlines, pushed the boundaries of artistic expression. Although initially controversial and criticized, this technique, when later integrated with traditional line drawing, evolved into a sophisticated method for depicting atmospheric effects and rational spatial representation. Shunso introduced various novel techniques into the traditional world of Japanese painting, contributing significantly to its evolution. His mentor, Okakura Tenshin, and his peer, Yokoyama Taikan, deeply lamented his premature death. Taikan, even in his later years, would often remark, "Shunso was the true genius. If he had lived, he would have been far superior to me." This highlights the immense respect and recognition for Shunso's talent among his contemporaries. His meticulous attention to detail extended even to his signatures and seals (rakkan and inshō), which are said to reflect his transparent and calm personality, and whose changes align with the evolution of his painting style.

7.2. Contemporary and Later Assessments

During his lifetime, Shunso's moro-tai style faced strong criticism, being derided as "vague" and lacking the precision of traditional Japanese painting. However, his persistence and subsequent integration of traditional techniques with his innovations gradually earned him recognition. His success at national exhibitions like the Bunten, particularly the highest award for Ochiba in 1909, marked a turning point in his contemporary assessment. In later periods, his contributions have been widely acknowledged as foundational to modern Nihonga. A large retrospective exhibition of his work was held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo's Art Museum Special Gallery in 2014, further solidifying his legacy and demonstrating the enduring relevance of his artistic vision.

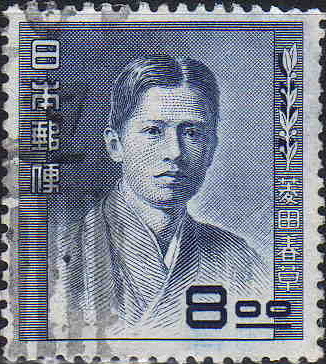

8. Philately

Hishida Shunso and his artworks have been honored on Japanese commemorative postage stamps. In 1951, Hishida Shunso himself was featured as the subject of a commemorative postage stamp as part of the Cultural Leaders Series issued by Japan Post. Later, in 1979, one of his most famous works, Black Cat, was selected as the subject of a commemorative postage stamp as part of the Modern Art Series.

9. Memorials and Homages

To honor Hishida Shunso's legacy, his birthplace in Nakanomachi, Iida City, was developed into the Hishida Shunso Birthplace Park (菱田春草生誕地公園Hishida Shunso Seitan-chi KōenJapanese), which opened on March 29, 2015. The park features a roofed bench that recreates the veranda of his childhood home, along with a garden planted with the flowers he favored in his paintings. The park's maintenance is overseen by a local residents' organization called the "Shunso Park Lovers' Association." The Iida City Museum also has a permanent exhibition room dedicated to Hishida Shunso, showcasing his works and preserving his connection to his hometown.