1. Overview

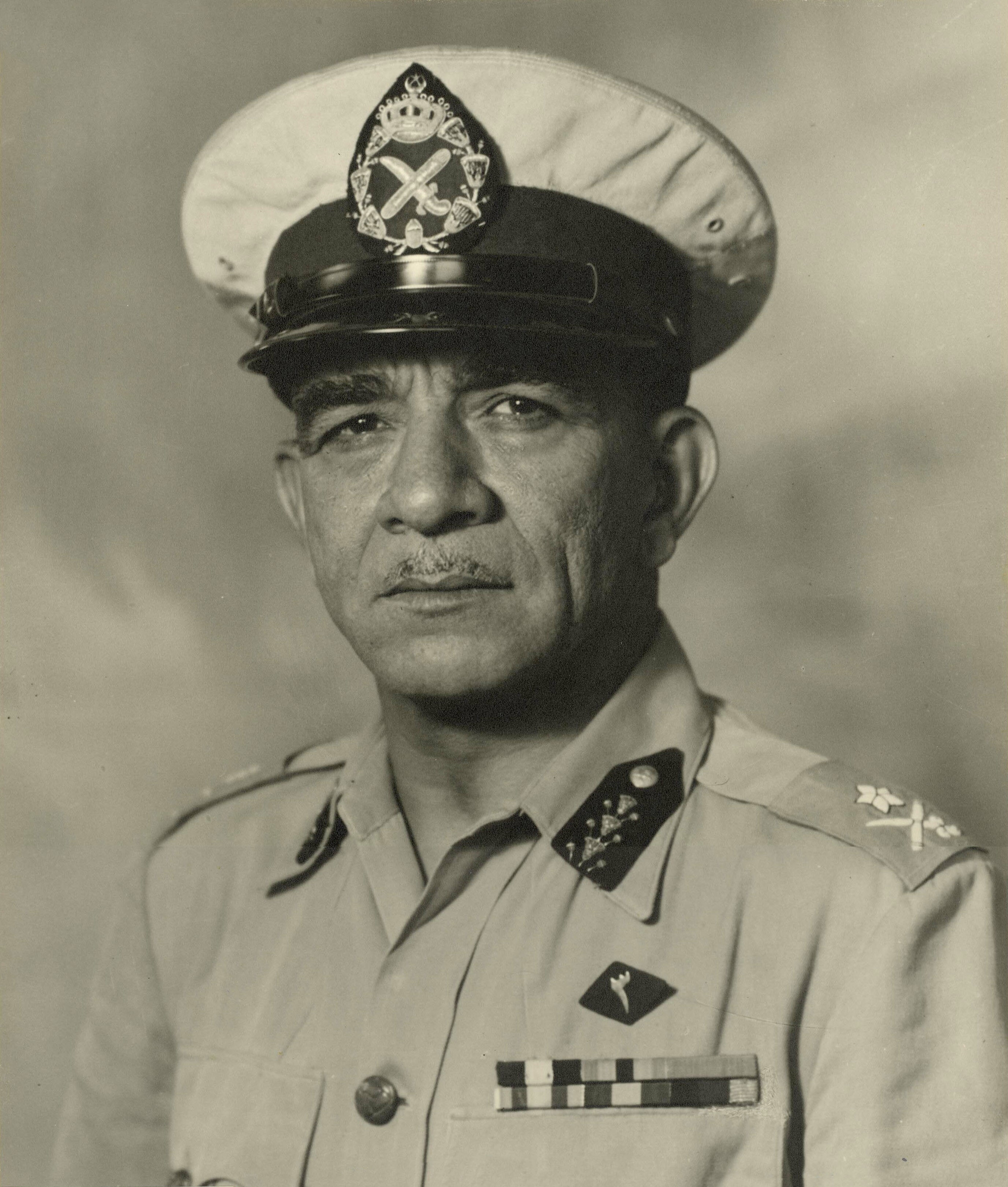

Mohamed Naguib (محمد نجيبmæˈħæmmææd næˈɡiːbArabic), born on 19 February 1901, was a distinguished Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who played a pivotal role in the 1952 Egyptian Revolution. Alongside Gamal Abdel Nasser, he was a principal leader of the Free Officers Movement that ultimately toppled the monarchy of Egypt and Sudan, leading to the establishment of the Republic of Egypt. A highly decorated general wounded multiple times in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Naguib was chosen to lead the Free Officers due to his esteemed military background and national popularity, providing a reassuring figure to the Egyptian public and lending legitimacy to the revolutionary cause. He served as the head of the Revolutionary Command Council, Prime Minister, and subsequently became the first President of Egypt from 1953 to 1954. During his presidency, he successfully negotiated the independence of Sudan and the complete withdrawal of British troops from Egypt. His tenure, however, was marked by an escalating power struggle with Gamal Abdel Nasser and other Free Officers, leading to his forced resignation and subsequent house arrest. Naguib advocated for a more civilian and democratic form of governance, contrasting with the military-dominated path favored by Nasser, a stance that ultimately led to his downfall. He passed away on 28 August 1984 in Cairo.

2. Early Life and Education

Mohamed Naguib was born on 19 February 1901 in Khartoum, then part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. He was the eldest of nine children born to Youssef Naguib and Zohra Ahmed Othman. His father, Youssef Naguib, was a ranking officer in the Egyptian Armed Forces from a prominent Egyptian family of army officers. His mother, Zohra, hailed from the esteemed Shaigiya tribe.

q=Khartoum|position=right

Naguib spent his early childhood in Khartoum, where he developed a critical view of British colonial rule, sometimes receiving corporal punishment from his British tutors for his outspokenness. In his youth, he initially aimed to become a translator and dedicated himself to language studies, mastering Italian, English, French, and German. He later pursued studies in political science and law. Naguib attended secondary and military school at Gordon Memorial College in Khartoum, graduating in 1918. After his father's death in 1916, Naguib moved to Cairo, Egypt.

He formally entered the Egyptian Military Academy in April 1917, though he did not complete a doctoral degree at the time. Parallel to his military career, he continued his legal studies, earning a Bachelor of Law degree in 1923. In 1927, he made history as the first Egyptian military officer to obtain a law license. His academic pursuits continued, leading to a postgraduate degree in political economy in 1929 and another postgraduate degree in civil law in 1931. Notably, in 1929, he attended lectures by then-Prime Minister Mostafa El-Nahas, who advocated that political parties and parliamentary systems should restrain the king's excesses and that the military should not intervene in politics. This early exposure to democratic principles significantly shaped Naguib's future political convictions. Naguib also studied Hebrew, and after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, he mandated Hebrew language learning at the Military Academy, enabling Egyptian military personnel to intercept Israeli communications.

3. Military Career

Mohamed Naguib's military career began officially on 23 January 1918, when he graduated from the Military Academy. On 19 February 1918, he was dispatched to Sudan as an attachment to the 17th Infantry Battalion, coincidentally the same unit his father had served in. In 1923, he joined the Egyptian Royal Guard.

He steadily rose through the ranks of the Egyptian military. In December 1931, Naguib was promoted to the rank of captain. He transferred to the border patrol in Arish in 1934, where he was involved in intercepting smugglers across the Sinai Peninsula. He was part of the military committee tasked with implementing the terms of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936. In 1937, he founded a newspaper for the Egyptian Armed Forces in Khartoum. On 6 May 1938, he was promoted to major. In 1938, he declined an an invitation to participate in a joint military exercise with the British forces in Marsa Matruh.

In 1940, Naguib had an audience with King Farouk I, where despite a positive atmosphere, Naguib refused to kiss the King's hand, opting instead for a handshake, indicating an early assertion of independence. In February 1942, during the Abdeen Palace incident of 1942, in which the British Ambassador Miles Lampson surrounded the palace with British troops to compel King Farouk to dismiss an anti-British government, Naguib was outraged by the King's perceived weakness. He tendered his resignation, stating he was ashamed to wear his uniform for failing to protect the King. His resignation was refused by palace officials who thanked him for his actions. Around the same time, he was mugged by a drunken British soldier, further fueling his anti-British sentiments.

Naguib continued to advance within the military hierarchy. In 1944, he achieved the rank of lieutenant colonel and was appointed regional governor of the Sinai Peninsula. He assumed leadership of the mechanized infantry in the Sinai in 1947 and was promoted to brigadier general in 1948. In the summer of 1949, he was promoted to Major General and became the Commander-in-Chief of the Border Guards. In 1950, he became Lieutenant General and Chief of Staff, a position that brought him reluctantly into close proximity with the King's personal guard.

His performance during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War was particularly outstanding, where he was wounded seven times. For his distinguished service, he was awarded the first military star of Fuad and the honorary title of Bey. His bravery and leadership in the war earned him significant national popularity.

He was subsequently appointed director of the Egyptian Military Academy, a position where he would eventually meet the members of the Free Officers Movement.

4. Free Officers Movement and Revolution

The period leading to the 1952 Revolution was characterized by escalating political instability, British influence, and internal discontent, setting the stage for Mohamed Naguib's involvement with the Free Officers Movement and his crucial role in the revolutionary events that transformed Egypt into a republic.

4.1. Free Officers Movement Activities

Mohamed Naguib was first introduced to the Free Officers Movement by Abdel Hakim Amer during his directorship of the Royal Military Academy in Cairo. The Free Officers were a clandestine group of nationalist army officers, primarily veterans of the unsuccessful nationalist uprisings of 1935-36 and 1945-46, as well as the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. They harbored fierce opposition to the continued presence of British military personnel in Egypt and Sudan, which had persisted since 1882, and the extensive political influence the United Kingdom exerted over Egyptian affairs. Furthermore, they viewed the Egyptian and Sudanese monarchy under King Farouk as weak, corrupt, and utterly incapable of safeguarding Egyptian and Sudanese national interests, particularly against the United Kingdom and the newly proclaimed State of Israel. They held King Farouk directly responsible for the mismanagement of the war in Palestine, which resulted in the loss of 78% of the former Mandate for Palestine and the displacement or exile of approximately three-quarters of Palestine's Muslim and Christian population.

The movement was initially led by Gamal Abdel Nasser and comprised exclusively servicemen under 35 years of age from modest socioeconomic backgrounds. Nasser, also a veteran of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, recognized the movement's need for an older, distinguished officer to gain credibility and be taken seriously by the public and the broader military establishment. The highly respected and nationally popular Naguib emerged as the obvious choice, and he was formally invited to assume leadership of the movement around 1950. Revolutionary committee members of the Free Officers, through Naguib's aide Abdel Hakim Amer, successively contacted him. Naguib, understanding he was being tested, did not resent it and accepted the leadership role.

While Naguib's leadership successfully strengthened the Free Officers Movement, it soon became a source of significant internal friction and ultimately led to a power struggle between the elder Naguib and the younger Nasser. Historians note that Naguib genuinely perceived his position and duty as being the movement's legitimate leader, advocating for a transition to civilian and parliamentary rule. However, the younger Free Officers, including Nasser, viewed him more as a symbolic figurehead who would defer to the collective decision-making of the movement, effectively limiting Naguib's role. This fundamental difference in vision for the future of Egypt's governance would later lead to their dramatic clash. In January 1952, Naguib's election as president of the officers' club, defeating the King's faction, further solidified the Free Officers' influence within the military. This expansion of their power alarmed King Farouk I, who began plotting Naguib's dismissal, but the Free Officers' coup occurred before he could execute his plan.

4.2. The 1952 Egyptian Revolution

The Egyptian Revolution of 1952, a pivotal moment in Egypt's modern history, began on 23 July 1952, when the Free Officers launched a coup d'état to depose King Farouk. At approximately 1:00 AM, the military seized control. Naguib was immediately appointed Commander in Chief of the Army, a crucial move designed to ensure the unwavering loyalty of the armed forces to the Revolution. His celebrated status as a national hero of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, coupled with his affable personality and an demeanor of an elder statesman, made him a reassuring figure to the Egyptian public, who had no prior exposure to Nasser or the other, younger Free Officers. Naguib quickly established the Revolutionary Command Council, of which he became chairman, and began advocating for the legitimacy of the revolution to both domestic and international audiences.

Initially, the Free Officers decided to govern through Aly Maher Pasha, a former prime minister renowned for his strong opposition to the United Kingdom's occupation and interference in Egyptian affairs. The prospect of British intervention on behalf of King Farouk presented the gravest threat to the nascent revolution. However, the situation was defused the following evening, on 24 July, when Naguib met with British diplomat John Hamilton. During this crucial meeting, Hamilton assured Naguib that the British government supported King Farouk's abdication, viewed the coup as an internal Egyptian matter, and would only intervene if British lives and property in Egypt were perceived to be in danger. This message provided the Free Officers with the necessary assurance to proceed with deposing the King.

On the morning of 26 July 1952, Aly Maher Pasha arrived at Ras El Tin Palace, where King Farouk was residing, to deliver an ultimatum from Naguib: Farouk was to abdicate his throne and depart from Egypt by 6:00 PM the following day, or Egyptian troops gathered outside the palace would storm it and arrest him. Farouk acceded to the terms of the ultimatum. The next day, in the presence of Maher and the United States Ambassador Jefferson Caffery, Farouk boarded the Royal yacht Mahrousa and left Egypt. In his memoirs, Naguib recounted that his journey to the dock to meet the deposed Farouk was delayed by throngs of people celebrating the success of the Revolution. Ambassador Caffery confirmed that Naguib was frustrated at missing the former King's initial departure. Upon his arrival at the dock, Naguib immediately boarded a small vessel to meet Farouk on the Mahrousa and formally bid him farewell. During this final encounter, King Farouk reportedly told Naguib, "Your mission is a difficult one. Governing Egypt is not easy." Naguib later expressed that he felt no joy in the King's defeat.

4.3. Establishment of the Republic

Following the deposition of King Farouk, his infant son, Fuad II, nominally succeeded him as the last King of Egypt. This succession was a strategic maneuver designed to deny the United Kingdom any pretext for intervention, as it allowed the revolutionaries to maintain publicly that their opposition was directed solely at the corrupt regime of Farouk, rather than the monarchy itself. However, after effectively consolidating their power, the Free Officers swiftly moved to implement their long-held plans for abolishing the monarchy.

On 7 September 1952, Aly Maher's government resigned, and Mohamed Naguib was appointed Prime Minister. He also played a key role in establishing the Royal Regent Council, with Nasser serving as the Minister of Interior. As Prime Minister, Naguib, alongside Nasser, led the new government. On 18 June 1953, nearly eleven months after the revolution, the revolutionaries formally stripped the infant King Fuad II of his title, officially declared the end of the Kingdom of Egypt, and announced the establishment of the Republic of Egypt. With this declaration, Mohamed Naguib was sworn in as its first President of Egypt, simultaneously retaining his position as Prime Minister and Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council.

5. Presidency

Mohamed Naguib's presidency marked a transformative period for Egypt, as he became the first head of state of the newly established republic. His tenure, however, was also characterized by significant internal power struggles that ultimately led to his downfall.

5.1. Key Activities During Presidency

Upon the declaration of the Republic, Naguib was sworn in as its first President, also holding the positions of Prime Minister and Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. In Western media, Naguib was often referenced as being the first native Egyptian ruler of Egypt since the Roman conquest of Egypt (which occurred in 30 BC), or even tracing back to Pharaoh Nectanebo II, whose reign ended in 342 BC, due to the non-Egyptian ancestry of Muhammad Ali Pasha (the progenitor of the Muhammad Ali dynasty) and earlier dynasties that had governed Egypt. Naguib himself famously objected to this characterization, stating:

"It has been said in the foreign press that I am the first Egyptian to govern Egypt since Cleopatra. Such words flatter but they do not align with our knowledge of our own history. For the sake of glorifying our own Blessed Movement, are we to say that the Fatimids were never Egyptian despite their centuries in Egypt? Do we now deny our kinship with the Ayyubids because of their origin even as we join Saladin's eagle with the Liberation Flag as the symbol of our Revolution? And what of the members of the Mohammed Ali dynasty? Should our grievances against the former King and the flawed and corrupt rulers before him blind us to the nationalism of Abbas Hilmi II, whose devotion to Egypt against the occupiers cost him his throne, or the achievements of Ibrahim Pasha, the very best of the dynasty, who himself declared that the Sun of Egypt and the water of the Nile had made him Egyptian? Are we now to go through the family histories of all Egyptians and invalidate those born to a non-Egyptian parent? If so, I must start with myself. It is fairer and more accurate to say that we are all Egyptians, but I am the first Egyptian to have been raised from the ranks of the people to the highest office to govern Egypt as one of their own. It is an honour and a sacred burden great enough without the embellishments that foreign observers would add to it."

During his time as president, Naguib pursued several crucial policy objectives. A major achievement was the successful negotiation for Sudan's independence. Previously a condominium of Egypt and the United Kingdom, Sudan gained full independence due to his efforts. Another significant accomplishment was the negotiation for the complete withdrawal of all British military personnel from Egypt, ending decades of British occupation and interference in Egyptian sovereignty. These negotiations were central to fulfilling the revolutionary movement's nationalist goals.

5.2. Power Struggle and Forced Resignation

Despite his public image and initial leadership role, the true power within the new government increasingly lay with Gamal Abdel Nasser and the younger members of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). Naguib, who had always maintained a skepticism about military-led governance and advocated for a swift return to civilian, parliamentary politics, began to show signs of political independence. He notably distanced himself from the RCC's more radical land reform decrees and sought closer ties with Egypt's established political forces, particularly the Wafd Party and the Muslim Brotherhood. This divergence from the RCC's agenda and his attempts to broaden political participation clashed fundamentally with Nasser's vision for a more centralized, military-controlled government.

The inherent conflict between Naguib's belief in civilian rule and Nasser's preference for military authority became increasingly pronounced. The RCC, which made decisions by majority vote, gradually limited Naguib's powers, even though he was its chairman. In late 1953, Nasser escalated the conflict by publicly accusing Naguib of supporting the recently outlawed Muslim Brotherhood and harboring dictatorial ambitions. A brief but intense power struggle ensued between Naguib and Nasser for control over the military and the direction of Egypt.

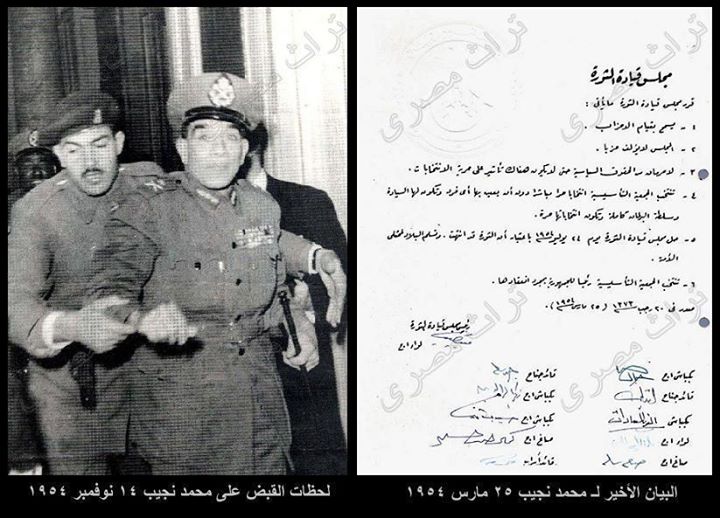

Nasser ultimately emerged victorious from this struggle. On 25 February 1954, the Revolutionary Command Council removed Naguib from his position as Prime Minister, accusing him of "seeking unacceptable absolute power." Nasser then assumed the premiership himself. This move sparked significant public backlash, forcing Nasser to reinstate Naguib as Prime Minister in March 1954. However, Naguib resigned again in April, once more yielding the premiership to Nasser. The final blow came on 14 November 1954, when Naguib was accused of conspiring with the Muslim Brotherhood to assassinate Nasser. He was consequently removed from the presidency and forced to resign. Nasser succeeded him as president, consolidating his power over Egypt.

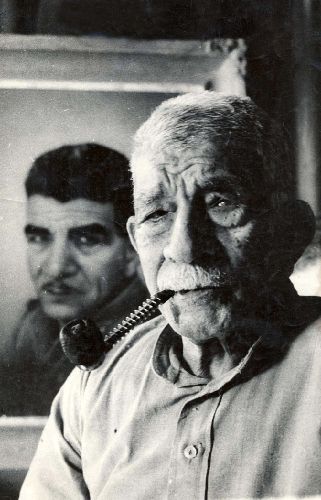

6. Post-Presidency Life and Death

After his forced resignation, Mohamed Naguib's public life effectively ended, as he was placed under strict surveillance and isolation by the new regime.

6.1. House Arrest and Release

Following his forced resignation from the presidency in November 1954, Mohamed Naguib was placed under informal house arrest. He was confined to a suburban villa in Cairo, owned by Zeinab Al-Wakil, the wife of former Prime Minister Mostafa El-Nahas. During this period, he was largely cut off from public life and remained under constant surveillance by Nasser's regime.

His period of house arrest lasted until 1971. It was President Anwar Sadat, who succeeded Nasser, who eventually ordered Naguib's release.

6.2. Personal Life

Mohamed Naguib was married and had four children: three sons named Farouk, Yusuf, and Ali, and one daughter. Tragically, his daughter passed away in 1951. In August 1952, shortly after the revolution, Life magazine reported that his eldest son, Farouk, who was 14 years old at the time, was planning to change his name, possibly to distance himself from the deposed King Farouk.

6.3. Death and Funeral

Mohamed Naguib passed away on 28 August 1984, in Cairo, Egypt, at the age of 83. The cause of his death was liver cirrhosis.

q=Cairo|position=left

His passing was marked by a military funeral, a significant event given his previous isolation and the circumstances of his removal from power. The funeral was attended by then-President Hosni Mubarak, a gesture seen by many as a posthumous recognition of Naguib's historical role. Naguib's coffin, draped in the Egyptian flag, was carried on a gun carriage drawn by six horses, while brass bands played solemn funeral music. Hundreds of mourners, including government officials, foreign dignitaries, and family members, marched behind the carriage, reflecting a public acknowledgment of his contributions to Egypt's revolution and early republican history.

7. Legacy and Assessment

Mohamed Naguib's legacy is complex, shaped by his initial leadership in the Egyptian Revolution, his brief but impactful presidency, and his subsequent marginalization. His contributions and the controversies surrounding his downfall continue to be assessed by historians.

7.1. Memoirs and Commemoration

Shortly before his death in 1984, Naguib published his memoirs under the title I Was a President of Egypt (كنت رئيسا لمصرArabic). The book gained wide circulation and was subsequently translated into English as Egypt's Destiny. The memoirs offered his personal account of the revolution, his time in office, and the power struggle that led to his ouster, providing valuable insight into a crucial period of Egyptian history from his perspective. The book was reissued several times.

In recognition of his historical importance, several places and honors have been named after him. A station of the Cairo Metro is named in his honor. A major road in the Al Amarat District of Khartoum, Sudan, also bears his name, acknowledging his birth in the city and his role in Sudanese independence. In December 2013, interim Egyptian President Adly Mansour posthumously awarded Naguib the Order of the Nile, Egypt's highest state honor. The prestigious award was received by his son, Mohamed Yusuf.

7.2. Historical Assessment and Controversy

Historical assessments of Mohamed Naguib present a nuanced view of his achievements and controversies, particularly concerning his relationship and power struggle with Gamal Abdel Nasser. He is widely recognized for his distinguished military career, especially his heroic performance during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, which earned him immense national popularity and respect. This public image was crucial in legitimizing the Free Officers' coup in 1952, as he provided a reassuring and familiar figure at the helm of a radical change.

However, Naguib's historical standing is inevitably intertwined with the events of his forced resignation. He is often seen as a figure who genuinely sought to transition Egypt from military rule to a more democratic, civilian-led government. His efforts to engage with established political parties like the Wafd and the Muslim Brotherhood, and his skepticism towards prolonged military control, distinguished him from Nasser and the more authoritarian elements within the Free Officers. This perspective highlights Naguib as a proponent of parliamentary politics, a stance that ultimately alienated him from Nasser, who favored a centralized, military-dominated regime. The accusations leveled against him by Nasser, including supporting the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood and harboring dictatorial ambitions, are often viewed critically as pretexts for Nasser to consolidate his own power. Naguib's subsequent house arrest further underscores the autocratic nature of the regime that followed. His re-evaluation in recent decades, including posthumous honors, signifies a shift towards acknowledging his foundational role in the republic and recognizing the complexities of the early revolutionary period.