1. Overview

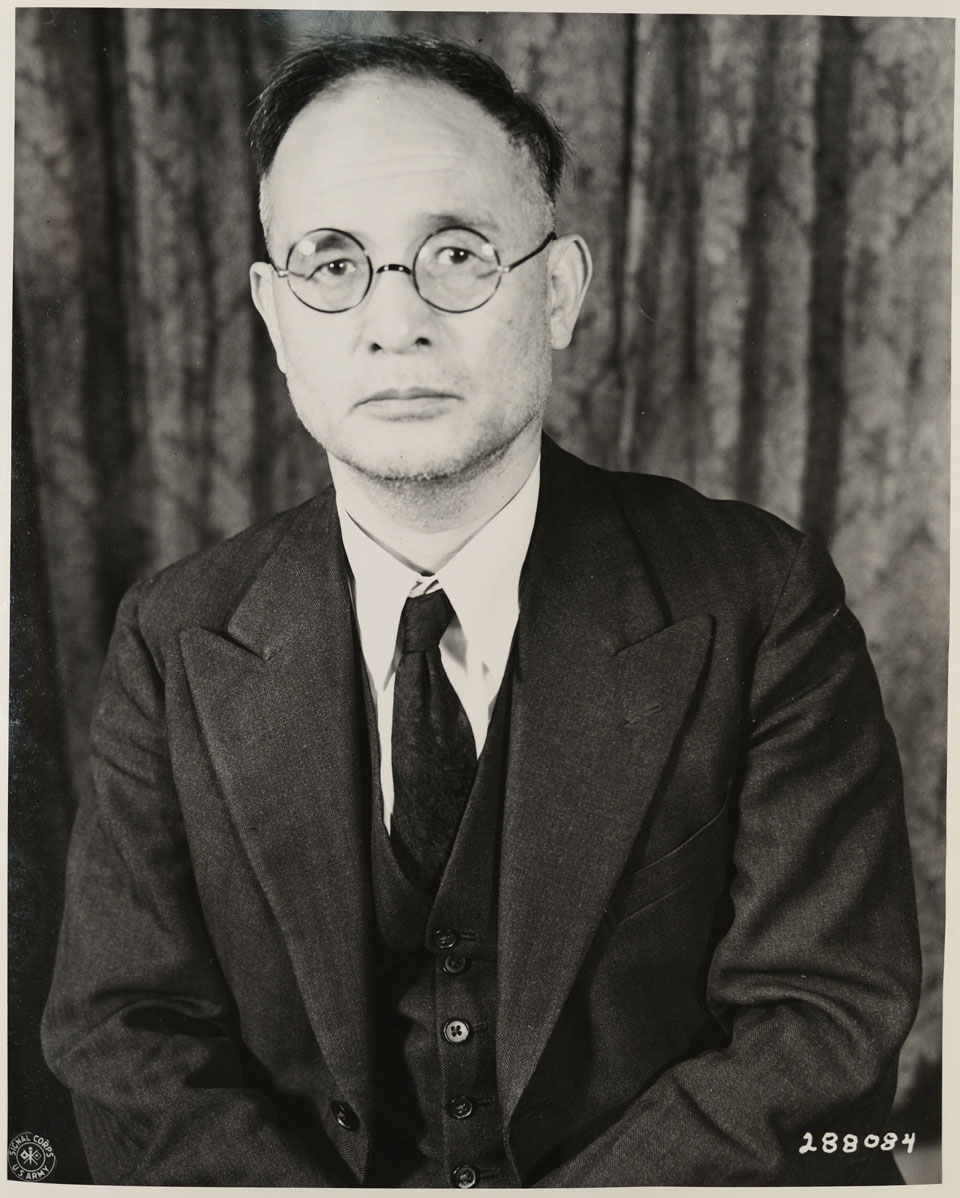

Mamoru Shigemitsu (重光 葵Shigemitsu MamoruJapanese, July 29, 1887 - January 26, 1957) was a prominent Japanese diplomat and politician who played a crucial role in Japan's foreign policy during and after World War II. His career spanned multiple ambassadorships, three tenures as Foreign Minister, and a period as Deputy Prime Minister of Japan. Despite a significant personal injury sustained in a bombing incident in 1932, Shigemitsu remained a steadfast advocate for diplomatic solutions and peace, often clashing with the prevailing militarist factions within Japan.

A key moment in his career was his role as the civilian plenipotentiary who signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Japanese government on board the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945, officially ending World War II. Following the war, he was controversially tried and convicted as a war criminal by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, receiving a relatively lenient sentence due to his documented opposition to militarism and inhumane treatment of prisoners. After his parole, Shigemitsu returned to politics, actively contributing to Japan's post-occupation diplomatic reconstruction. He was instrumental in Japan's re-entry into the international community, notably leading efforts for normalization of relations with the Soviet Union and securing Japan's admission to the United Nations, reflecting a perspective that valued peace, international cooperation, and democratic development.

2. Early Life and Education

Mamoru Shigemitsu was born on July 29, 1887, in what is now part of the city of Bungo-ōno, Ōita Prefecture, Japan. He was the second son of Naonobu Shigemitsu, a local gentry (`士族`) who served as the chief of Ōno District, and Matsuko, the daughter of Kōgyō Shigemitsu. Due to the lack of children in his mother's ancestral home (the main Shigemitsu family), he was adopted and became the 26th head of the Shigemitsu family.

For his early education, Shigemitsu attended the old-system Kitsuki Junior High School and then the Fifth Higher School, where he specialized in German law. He subsequently enrolled in the Law School of Tokyo Imperial University, from which he graduated in 1911. Immediately after his graduation, he embarked on his career by entering the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in September 1911, as part of its 20th class, alongside notable contemporaries such as Hitoshi Ashida, Kensuke Horiuchi, and Kazue Kuwashima.

3. Diplomatic Career (Pre-War)

After joining the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Shigemitsu quickly began his overseas diplomatic assignments following World War I. His early postings included serving as a diplomatic attaché in Germany and as a Third Secretary at the Japanese Embassy in the United Kingdom. He also briefly held the position of consul at the Japanese consulate in Seattle, Washington, in the United States. His career further advanced with roles such as a member of the Japanese delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, Chief of the Treaty Bureau's First Section, First Secretary at the Japanese Legation in China, and Counselor at the Embassy in Germany. He then served as Consul General in Shanghai before being appointed Minister to China in 1930.

3.1. Manchurian Incident and Shanghai Incident

Following the Mukden Incident in September 1931, which saw a portion of the Japanese Army unilaterally seize control of Manchuria and escalate into an international crisis, Shigemitsu was actively engaged in various European capitals. He worked to mitigate international alarm over Japan's military actions. He expressed deep frustration, stating in his work, "Showa no Dōran" (昭和の動乱Turbulence of ShowaJapanese), that "The international standing of Japan, built up since Meiji, was destroyed overnight, and our international credibility rapidly declined, which is unbearable for those in diplomatic service." He tirelessly advocated for a cooperative diplomatic approach to resolve the situation.

In January 1932, when the First Shanghai Incident erupted, Shigemitsu played a crucial role in enlisting the support of Western nations to broker a ceasefire between the Kuomintang Army and the Imperial Japanese Army. His efforts were successful, leading to a ceasefire agreement.

3.2. Hongkew Park Bombing Incident

On April 29, 1932, while attending a celebration for Emperor Hirohito's birthday (Tenchōsetsu) at Hongkew Park in Shanghai, Shigemitsu was severely injured in a bomb attack carried out by Yoon Bong-Gil, a Korean independence activist. The bombing killed General Yoshinori Shirakawa and wounded several others. Shigemitsu lost his right leg in the attack and subsequently used a prosthetic leg, weighing approximately 22 lb (10 kg), and a cane for the remainder of his life.

Despite the intense pain, Shigemitsu remained resolute in his diplomatic mission. He famously declared, "If the ceasefire is not achieved, the nation's future will fall into an irreversible predicament," emphasizing the critical importance of the agreement. Seven days after the incident, on May 5, he signed the Shanghai Ceasefire Agreement just before undergoing surgery for the amputation of his right leg. Among those also injured in the attack was Admiral Kichisaburō Nomura, who lost an eye but later served as Foreign Minister and Ambassador to the United States, playing a key role in US-Japan negotiations. When questioned why he did not flee during the bombing, Shigemitsu reportedly replied that it was "during the national anthem."

The First Shanghai Incident, which China brought before the League of Nations, led to the adoption of a resolution on February 24, 1933, deeming the Japanese military's actions in Manchuria unjust (based on the Lytton Report). With a vote of 42 nations in favor and only Japan against, Japan declared its withdrawal from the League of Nations, leading to its increasing isolation in the international community. Shigemitsu, reflecting on this period, noted in his writings that "Western nations strived to realize nationalism in Europe. However, their efforts were hardly directed towards Asia. The West colonized most of Africa and Asia and did not recognize the international personality of Asian peoples," expressing his anger at the perceived hypocrisy of white dominance in Asia.

3.3. Ambassadorial Roles

Following the Shanghai Incident, Shigemitsu served as Ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1936 to 1938. During this tenure, he was involved in negotiating settlements for Russo-Japanese border clashes, including the Changkufeng Hill and Kanchatzu Island incidents. Despite his efforts, he faced opposition from the Soviet Foreign Ministry and was criticized by Soviet media as an "incompetent diplomat." Interestingly, Kōki Hirota, then Foreign Minister, had appointed Shigemitsu to Moscow with consideration for his injury, a move that ironically backfired.

Shigemitsu then became Japan's Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1939 to June 1941, a period marked by deteriorating Anglo-Japanese relations, most notably the Tientsin incident of 1939, which brought Japan to the brink of war with Britain. He strove to improve relations and urged the British government to cease aid to the Chiang Kai-shek regime. He also sent numerous accurate reports on the European situation back to Tokyo.

He was highly critical of the foreign policies of Yōsuke Matsuoka, particularly the Tripartite Pact signed on September 27, 1940, by Matsuoka as Foreign Minister under the Second Konoe Cabinet. Shigemitsu warned that this pact would further intensify anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. On his way back from Britain, he spent two weeks in Washington, D.C., conferring with Ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura in an attempt to arrange direct face-to-face negotiations between Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

However, Shigemitsu's persistent attempts to avert World War II angered the militarists in Tokyo. Just two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, on December 19, 1941, he was removed from his post as Ambassador to the UK and sidelined with an appointment as Ambassador to the Japanese-sponsored Reorganized National Government of China (Wang Jingwei regime). In China, Shigemitsu argued that the true success of the proposed Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere depended on Japan treating China and other Asian nations equally. He asserted that "Japan must not oppress or infringe upon the interests of East Asian peoples by using them as a stepping stone. This is because military development cannot gain the understanding of East Asian peoples."

4. Role during World War II

Mamoru Shigemitsu served as Foreign Minister during the Hideki Tōjō and Kuniaki Koiso administrations. He also held the position of Minister of Greater East Asia concurrently for a period.

4.1. Stance on Militarism and the War

Shigemitsu was a vocal critic of Japanese militarism and its foreign policies. He had strongly opposed the Tripartite Pact, warning that it would exacerbate anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. His consistent efforts to advocate for diplomatic solutions and peace, even as Japan moved towards war, often put him at odds with the powerful military factions in Tokyo.

On April 20, 1943, in a move widely seen as an indication that Japan might be preparing for a collapse of the Axis Powers, Prime Minister Tōjō replaced Foreign Minister Masayuki Tani with Shigemitsu, who was known for his steadfast opposition to the militarists. Shigemitsu, therefore, served as Foreign Minister during the Greater East Asia Conference in November 1943. Although he initially opposed the establishment of the Ministry of Greater East Asia, he worked to implement his vision for a cooperative East Asia as a key advisor to Prime Minister Tōjō. The Greater East Asia Conference declared that the nations of Greater East Asia would mutually respect each other's autonomy and independence and cooperate on an equal footing, without discrimination. From July 22, 1944, to April 7, 1945, he concurrently served as Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Greater East Asia in the Koiso administration. He briefly served as Foreign Minister again in August 1945 in the Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko administration, just before Japan's surrender.

4.2. Signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender

As the civilian plenipotentiary representing the Japanese government, Mamoru Shigemitsu undertook the monumental task of signing the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on September 2, 1945. The historic ceremony took place on the deck of the American battleship USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. He co-signed the document alongside General Yoshijirō Umezu, who represented the Imperial General Headquarters.

The day before the signing, Emperor Hirohito reportedly told Shigemitsu, "Let us make this day of mourning the day of Japan's new birth. Only then can we attend the ceremony with our heads held high!" Shigemitsu himself viewed this moment not as "a disgraceful endpoint, but a starting point for rebirth." He expressed his sentiments in a poem: "I wish that as my nation prospers in the future, there will be many who scorn my name."

Upon the arrival of the GHQ forces at Atsugi Airfield, Shigemitsu, then Foreign Minister and Minister of Greater East Asia in the Higashikuni Naruhiko cabinet, issued strict orders to the city of Yokohama. He demanded that British and American troops not be allowed directly into the capital, that direct military rule be prevented, and that military scrip not be used. He vehemently protested to Douglas MacArthur against the initial Allied plan for direct military rule, arguing that it deviated from the Potsdam Declaration, which recognized Japan's sovereignty, and that Japan, unlike Germany, still possessed a functioning government. He demanded the immediate withdrawal of any such proclamation, and his strong protest ultimately contributed to the Allied occupation policy being implemented as indirect rule through the existing Japanese government.

During the signing ceremony on the USS Missouri, American sailors reportedly struggled to hoist Shigemitsu onto the battleship's deck due to his prosthetic leg. Despite this, Shigemitsu remained composed and maintained a dignified posture. While some anecdotes suggest he fumbled the signing, which was interpreted by William Halsey Jr. as an "ugly delay" prompting a reprimand, Shigemitsu's overall demeanor reflected his resolve in this pivotal moment of history.

5. Post-War and War Crimes Trial

Despite his well-known opposition to the war and militarism, Mamoru Shigemitsu was taken into custody by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and held in Sugamo Prison as an accused war criminal. This was largely at the insistence of the Soviet Union.

5.1. War Crimes Charges and Imprisonment

Shigemitsu was accused of waging an aggressive war and for failing to do enough to protect prisoners-of-war from inhumane treatment. His indictment was strongly opposed by Joseph Grew, the former United States Ambassador to Japan, who provided a signed deposition in Shigemitsu's favor, and by Joseph B. Keenan, the chief prosecutor for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Despite these protests, and the initial lack of intent by GHQ to prosecute him, the Soviet representative prosecutor, Sergei A. Golunsky, who arrived in Japan on April 13, 1946, adamantly demanded Shigemitsu's indictment due to his service as Foreign Minister in the Tōjō and Koiso cabinets during World War II. The American Democratic administration at the time ultimately yielded to the Soviet pressure, as the Soviets threatened to withdraw from the trial if their demands were not met. Consequently, Shigemitsu was arrested and indicted on April 29, the very day the indictments were issued.

5.2. International Military Tribunal for the Far East

Shigemitsu's case proceeded to trial before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial. His defense was diligently handled by lawyers such as Kenzo Takayanagi and George A. Furness. On November 12, 1948, he was found guilty of waging an aggressive war and for not adequately protecting prisoners-of-war. He was sentenced to seven years in prison, which was the lightest punishment handed down to any individual convicted at the trial.

The tribunal was notably lenient towards Shigemitsu, acknowledging his consistent opposition to Japanese militarism and his protests against the inhumane treatment of POWs. The verdict, however, was met with surprise and criticism from many, including Japanese and Western media, who had widely anticipated his acquittal. Many viewed the guilty verdict as a political compromise by GHQ to appease the Soviet Union. Even those within Sugamo Prison expressed astonishment; Captain Bloom, a military police officer, stated, "I was surprised. No one doubted your innocence." Lieutenant Colonel Kenworthy, the military police commander, reportedly said, "The verdict will surely be overturned." Chief Prosecutor Keenan himself criticized the verdict, calling it "absurd" and stating that Shigemitsu was a "pacifist" who should have been acquitted.

5.3. Parole and Amnesty

After serving 4 years and 7 months of his sentence, Mamoru Shigemitsu was granted parole on November 21, 1950, and released from Sugamo Prison. He was met by his defense lawyers, Takayanagi and Furness, and shook hands with Lieutenant Colonel Davis, the prison's officer in charge, as staff applauded his departure. The parole status was formally ended in 1952, after the Treaty of San Francisco came into effect. In accordance with the treaty's provisions, his sentence was terminated by amnesty, agreed upon by the Japanese government and all nations that participated in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, marking his full reintegration into society.

6. Post-War Political Career and Diplomatic Reconstruction

Following the end of the occupation of Japan and the lifting of the public office purge, Mamoru Shigemitsu made a significant return to public life, playing a pivotal role in rebuilding Japan's foreign policy and international standing.

6.1. Return to Politics and Party Activities

In October 1952, Shigemitsu was elected to a seat in the Lower House of the Diet of Japan, representing the Ōita 2nd district, a position he held for three terms. After his release, he formed a short-lived political party called Kaishintō (Progressive Party), serving as its president from 1952 to 1954. In 1952, as the leader of an opposition party, he contended with Shigeru Yoshida for the position of Prime Minister, coming in second in the Diet's Prime Ministerial designation vote. Following the 1953 general election, when Yoshida's Liberal Party became a minority government, Shigemitsu refused a coalition offer but later accepted external cooperation after failing to secure support from both the left and right-wing Socialist parties for his own bid for Prime Minister.

He subsequently joined forces with Ichirō Hatoyama's faction to establish the Japan Democratic Party, where he served as vice president. In 1955, he participated in the conservative merger that led to the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

6.2. Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister

Shigemitsu concurrently served as Deputy Prime Minister of Japan and Foreign Minister from December 1954 to December 1956, under the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Ichirō Hatoyama cabinets. This marked his fourth tenure as Foreign Minister. During this period, he was responsible for spearheading Japan's efforts to restore its diplomatic relations and regain international credibility. His relationship with Prime Minister Hatoyama, however, was at times strained, partly due to Hatoyama's insensitive remarks about preferring "party politicians" over "bureaucratic politicians" for government administration, and Shigemitsu's more hardline stance on the Soviet Union compared to Hatoyama's priority of normalizing relations.

6.3. Key International Diplomatic Initiatives

In April 1955, Shigemitsu represented Japan at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, an assembly of 29 Asian and African nations. This conference marked Japan's first participation in a major international conference since its withdrawal from the League of Nations. At Bandung, Asian and African nations resolved to cooperate as a "third force," and Japan successfully garnered support for its bid to join the United Nations.

In August of the same year, Shigemitsu led a high-level Japanese delegation to the United States to advocate for a revision of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. However, this initiative was met with a cold reception from Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who was a primary architect of the treaty and reluctant to revisit it. Dulles unequivocally informed Shigemitsu that any discussion of treaty revision was "premature" because Japan lacked "the unity, cohesion, and capacity to operate under a new treaty arrangement." Consequently, Shigemitsu returned to Japan without achieving his objective.

The following year, in July 1956, Shigemitsu traveled to Moscow in an attempt to normalize diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and resolve the Kuril Islands dispute. The negotiations faced significant difficulties, particularly concerning the Northern Territories issue. Shigemitsu reportedly cabled Tokyo, suggesting that to conclude a peace treaty, Japan might have to accept the Soviet proposal of returning only the Habomai Islands and Shikotan Island. However, Prime Minister Hatoyama rejected this proposal, sending Shigemitsu to the Suez Conference and personally visiting Moscow to continue negotiations. Although Hatoyama's visit did not resolve the territorial dispute, it led to the signing of the Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956 on October 19, 1956, which restored diplomatic relations and secured the Soviet Union's non-opposition to Japan's UN membership, effectively shelving the territorial issue.

6.4. Pursuit of United Nations Membership

On September 1, Shigemitsu visited the United Nations Headquarters and hosted a reception, emphasizing that a economically recovered Japan could contribute significantly to the international community, thereby advocating for its UN membership. On December 18, 1956, the United Nations General Assembly unanimously approved Japan's admission, with all 76 member states voting in favor. Japan officially became the 80th member of the UN. Shigemitsu delivered Japan's acceptance speech to the General Assembly, declaring that "Japan can be a bridge between East and West," a statement met with applause from the attending delegations. Immediately after, he personally hoisted the Japanese flag high in the front garden of the UN Headquarters, reflecting his emotions in a poem: "The fog clears, the UN tower shines, and the Hinomaru flag is raised high."

Upon his return journey to Japan, Shigemitsu learned that the 3rd Hatoyama Ichirō cabinet had resigned on December 23, 1956, and the Tanzan Ishibashi cabinet had been formed. Consequently, he resigned from his post, and Nobusuke Kishi succeeded him as Foreign Minister. He reportedly told Toshikazu Kase, who accompanied him on the return trip, with a smile, "I have no regrets left." Shigemitsu remains the last Japanese Foreign Minister to have had a career as a professional diplomat.

7. Personal Life and Character

Mamoru Shigemitsu was often described by those who knew him as having "no flaws, which was his flaw." A defining aspect of his personal life was the loss of his right leg in the Hongkew Park bombing incident in 1932. From then on, he wore a prosthetic leg, which weighed approximately 22 lb (10 kg), and relied on a cane for mobility. Despite the significant physical challenge, even traveling long distances, he never showed any sign of being bothered by his condition. This composure was evident during the signing of the Instrument of Surrender on the USS Missouri, where, despite the difficulties American sailors faced in assisting him onto the ship due to his prosthetic leg, he remained calm and poised.

Shigemitsu held strong convictions and was not afraid to voice them. While imprisoned at Sugamo Prison, he heard news of Helen Keller's second visit to Japan. When some former generals in the prison disparaged her, saying she was "selling her blindness," Shigemitsu vehemently criticized them in his "Sugamo Diary" (巣鴨日記Sugamo NikkiJapanese), lamenting, "They are the truly pitiful blind in heart; what outrageous remarks. I grieve for the Japanese people."

He had a close relationship with Fumimaro Konoe, but after Japan's defeat, Shigemitsu was severely critical of Konoe's attempts to evade his own responsibility for the war by shifting all blame onto the Emperor and the military. He wrote, "The attitudes of the war responsibility suspects are all ugly. Especially that of Prince Konoe..."

His relationship with Prime Minister Ichirō Hatoyama, under whom he served as Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, was at times strained. Hatoyama's insensitive public statements about preferring "party politicians" over "bureaucratic politicians" in government administration caused friction with Shigemitsu, who was a career diplomat. Furthermore, Shigemitsu held a hardline stance on the Soviet Union, contrasting with Hatoyama's priority of normalizing relations, which also contributed to their disagreements.

When Allied forces arrived at Atsugi Airfield after the war, Shigemitsu, then serving as Foreign Minister and Minister of Greater East Asia, issued strict instructions to the city of Yokohama. He explicitly ordered that British and American troops should not be allowed directly into the capital, that direct military rule must be prevented, and that military scrip should not be used. While the first point was not fully realized, his firm stance influenced the indirect nature of the Allied occupation.

8. Death

In January 1957, approximately a year after his visit to the Soviet Union for diplomatic negotiations, Mamoru Shigemitsu died at the age of 69. He passed away from a myocardial infarction (heart attack), specifically an angina pectoris attack, at his summer home in Yugawara, Kanagawa Prefecture.

9. Legacy and Evaluation

Mamoru Shigemitsu's life and career left a complex and significant legacy in Japanese history, diplomacy, and politics. He is remembered as a figure who navigated the tumultuous periods of pre-war militarism, World War II, and post-war reconstruction with a consistent, albeit sometimes controversial, commitment to diplomacy and international cooperation.

9.1. Positive Assessments and Contributions

Shigemitsu is widely praised for his exceptional diplomatic skills and his consistent opposition to Japanese militarism throughout his career. He actively advocated for peaceful and diplomatic solutions even when the tide of public opinion and government policy was heavily influenced by military expansionism. His efforts to avert war, such as his warnings against the Tripartite Pact and his attempts to facilitate direct negotiations between Japan and the United States, are often highlighted as evidence of his foresight and dedication to peace.

His contributions to post-war Japan's international reintegration and democratic development are considered particularly significant. He played a pivotal role in restoring Japan's international standing, notably by representing Japan at the Bandung Conference and tirelessly working to secure Japan's admission to the United Nations. His success in achieving UN membership marked Japan's official return to the global community and symbolized its commitment to international cooperation. He believed that "Japan can be a bridge between East and West," a vision he articulated in his UN acceptance speech. His firm stance against direct military rule by the Allied forces after the surrender also contributed to the establishment of indirect rule, preserving a degree of Japanese sovereignty during the occupation.

9.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his efforts, Shigemitsu faced criticisms regarding his wartime role, particularly his service as Foreign Minister in the Tōjō and Koiso cabinets. While he opposed militarism, his continued participation in these governments led to accusations, especially from the Soviet Union, that he was complicit in the aggressive war. His conviction as a war criminal by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, despite the tribunal's leniency and the strong opposition from American prosecutors and his defense team, remains a point of controversy. Many observers at the time, including some Allied personnel, believed his conviction was a political compromise to satisfy Soviet demands, rather than a reflection of his actual culpability.

His political actions in the post-war period also drew criticism, such as his strained relationship with Prime Minister Hatoyama Ichirō and his hardline stance during negotiations with the Soviet Union regarding the Kuril Islands dispute, which ultimately led to the shelving of the territorial issue in favor of immediate diplomatic normalization.

9.3. Writings and Memoirs

Mamoru Shigemitsu was a prolific writer, and his published works provide valuable insights into his thoughts, experiences, and the diplomatic history of Japan. His significant writings include:

- Showa no Dōran (昭和の動乱Turbulence of ShowaJapanese) (1952): A two-volume work that was later translated into English as Japan and Her Destiny: My Struggle for Peace (1958).

- Gaikō Kaisōroku (外交回想録Diplomatic MemoirsJapanese) (1953).

- Sugamo Nikki (巣鴨日記Sugamo NikkiJapanese) (1953): His personal diary kept during his imprisonment in Sugamo Prison, offering a unique perspective on the Tokyo Trials and his reflections from behind bars.

He also authored several collections of diplomatic opinions and speeches, such as Revolutionary Diplomacy: Report by Minister Shigemitsu to China (1931), Collection of Major Speeches by Foreign Minister Shigemitsu (1955), and Collection of Statements by Foreign Minister Shigemitsu on His Visit to the U.S. (1955). Posthumous collections of his notes and records, including Mamoru Shigemitsu's Notes (1986, 1988) and Mamoru Shigemitsu: Supreme War Leadership Council Records and Notes (2004), further illuminate his perspective on critical historical events.

9.4. Honors and Commemorations

Mamoru Shigemitsu received numerous honors throughout his life and posthumously. He was awarded various Japanese orders, including the Order of the Sacred Treasure (6th, 4th, 3rd, and 1st class) and the Order of the Rising Sun (5th and 1st class, including the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun). He also received the Commemorative Medal of the 2600th Anniversary of the Imperial Year in 1940.

Posthumously, on January 26, 1957, he was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers (勲一等旭日桐花大綬章), the highest order in the Japanese honors system, in recognition of his significant contributions.

Shigemitsu also received permission to wear several foreign decorations, including:

- Manchukuo: Order of the Auspicious Clouds, 2nd Class (1934); Emperor's Visit to Japan Commemorative Medal (1935); Order of the Pillar of the State, 1st Class (1938).

- Republic of China (Wang Jingwei regime): Special Class Order of the Grand Cordon of the Auspicious Clouds (1943).

- Nazi Germany: Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle (1943).

Some of his personal belongings and artifacts are preserved and displayed at Musekian, the residence of his birth family in Kitsuki City, Ōita Prefecture. The city of Kitsuki also commemorates his legacy. There is also a Shigemitsu Mamoru Memorial Museum dedicated to his life and contributions.