1. Early Life and Education

Konstantinos Karamanlis was born on March 8, 1907, in the village of Proti, near the city of Serres in Macedonia. At the time of his birth, Macedonia was part of the Ottoman Empire, but it was annexed by Greece in 1913 following the First and Second Balkan War, at which point Karamanlis became a Greek citizen. His father, Georgios Karamanlis, was a teacher who had participated in the Greek Struggle for Macedonia between 1904 and 1908.

After spending his childhood in Macedonia, Karamanlis moved to Athens to pursue higher education. He earned a degree in law from the University of Athens. Upon completing his studies, he returned to Serres, where he began his career as a practicing lawyer. Due to health issues, Karamanlis did not participate in the Greco-Italian War. During the Axis occupation of Greece, he divided his time between Athens and Serres. In July 1944, he departed for the Middle East to join the Greek government in exile.

2. Early Political Career

Karamanlis entered politics with the conservative People's Party and was first elected as a Member of Parliament for Serres in the 1936 election at the age of 28. After World War II, he quickly rose through the ranks of Greek politics, significantly supported by his close friend and fellow party member, Lambros Eftaxias, who served as Minister for Agriculture.

Karamanlis's first cabinet position was as Minister for Labour in 1947. In 1951, he joined the Greek Rally party, led by Alexandros Papagos, along with many other prominent members of the People's Party. When the Greek Rally won the legislative election on September 9, 1951, Karamanlis was appointed Minister of Public Works in the Papagos administration. During this tenure, he earned admiration from the US Embassy for his efficient construction of road infrastructure and his effective administration of American aid programs.

3. First Premiership (1955-1963)

Karamanlis's initial period as Prime Minister was marked by significant efforts to modernize Greece's economy and infrastructure, alongside a proactive foreign policy aimed at European integration. However, it was also a time of political challenges and controversies that ultimately led to his resignation.

3.1. Economic and Social Policies

Following the death of Prime Minister Alexandros Papagos in October 1955, King Paul of Greece unexpectedly appointed the 48-year-old Karamanlis as prime minister, bypassing more senior politicians like Stephanos Stephanopoulos and Panagiotis Kanellopoulos. Upon assuming office, Karamanlis reorganized the Greek Rally party into the National Radical Union.

His government implemented a program of rapid industrialization, heavy investment in infrastructure, and improvements in agricultural production. These initiatives laid the groundwork for the post-war Greek economic miracle, with a notable five-year plan announced in 1959 (for 1960-1964) that emphasized industrial growth, agricultural improvement, and the promotion of tourism. A significant social reform during this period was the extension of full voting rights to women, which had been nominally approved in 1952 but remained dormant until Karamanlis's premiership. Karamanlis successfully won three successive elections in February 1956, May 1958, and October 1961, maintaining a parliamentary majority. However, this period was also criticized for its strong-arm tactics and suppression of left-wing and labor movements.

3.2. Foreign Policy and European Integration

In foreign affairs, Karamanlis shifted Greece's stance on the Cyprus problem. He abandoned the previous strategic goal of enosis (the unification of Greece and Cyprus) in favor of independence for Cyprus. In 1958, his government engaged in negotiations with the United Kingdom and Turkey, which culminated in the Zurich Agreement as a basis for Cyprus's independence. This plan was subsequently ratified in London by the Cypriot leader Makarios III in February 1959.

Karamanlis was a strong advocate for Greece's membership in the European Economic Community (EEC), pursuing an aggressive policy toward this goal as early as 1958. He viewed Greece's entry into the EEC as a personal dream and the fulfillment of what he termed "Greece's European Destiny," believing it would ensure political stability for a nation prone to military dictatorships. He personally lobbied European leaders, including Germany's Konrad Adenauer and France's Charles de Gaulle, leading to two years of intense negotiations with Brussels.

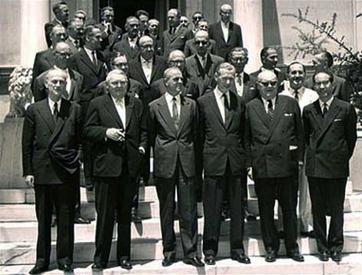

His persistent efforts bore fruit on July 9, 1961, when his government and European representatives signed the protocols of Greece's Treaty of Association with the European Economic Community in Athens. The signing ceremony was attended by high-level government delegations from the six-member bloc of Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Among the European delegates were German Vice-Chancellor Ludwig Erhard and Belgian Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak, a pioneer of the European Union and a recipient of the Karlspreis like Karamanlis.

This treaty significantly impacted Greece by ending its economic isolation and reducing its political and economic dependence on US economic and military aid, primarily channeled through NATO. Greece became the first European country outside the original six-nation EEC group to achieve associate member status. The association treaty came into effect in November 1962, envisioning Greece's full membership in the EEC by 1984, following the gradual elimination of all Greek tariffs on EEC imports. A financial protocol included in the treaty provided for community-subsidized loans to Greece of about 300.00 M USD between 1962 and 1972, aimed at increasing the competitiveness of the Greek economy in anticipation of full membership. However, this financial aid package and the accession protocol were suspended during the 1967-1974 military junta years, and Greece was temporarily expelled from the EEC. During the dictatorship, Greece also resigned its membership in the Council of Europe to avoid embarrassing investigations following allegations of torture.

3.3. Political Crises and Controversies

Karamanlis's first premiership was marked by several political crises and controversies that ultimately led to his resignation. The 1961 Greek legislative election saw his National Radical Union win 50.8 percent of the popular vote. However, both main opposition parties, the EDA and the Centre Union, denounced the results, alleging widespread voter intimidation and irregularities, including sudden massive increases in support for the National Radical Union against historical patterns and votes cast by deceased persons. The Centre Union, led by George Papandreou, claimed the election was rigged by shadowy "para-state" (παρακράτοςGreek, Modern) agents, including the army leadership, the Greek Central Intelligence Service, and the right-wing National Guard Defence Battalions, under a prepared emergency plan code-named Pericles. While irregularities certainly occurred, the existence of Pericles was never definitively proven, nor is it certain that the interference radically influenced the outcome. Nevertheless, Papandreou initiated an "unrelenting struggle" (ανένδοτος αγώνGreek, Modern) demanding new and fair elections.

Karamanlis's position was further undermined by the assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis, a leftist Member of Parliament, by right-wing extremists during a pro-peace demonstration in Thessaloniki in May 1963. These extremists were later found to have close links to the local gendarmerie. Karamanlis was reportedly shocked by the assassination and critically stated, "Who governs this country?" The opposition, particularly George Papandreou, heavily criticized him as a moral accomplice to the assassination.

The final blow to Karamanlis's government was his escalating conflict with the Palace in the summer of 1963. He opposed a projected visit by the royal couple to Britain, fearing it would provoke demonstrations against political prisoners still held in Greece since the Greek Civil War. Karamanlis's relations with the Palace had been deteriorating for some time, especially with Queen Frederika and the Crown Prince. He also clashed with King Paul over the King's opposition to proposed constitutional amendments that would empower the government, the royal family's extravagant lifestyle, and the King's near-monopoly over control of the armed forces. When the King rejected his advice to postpone the trip to London, Karamanlis resigned from the premiership and left the country.

Another significant controversy during his first premiership was the Merten affair. Max Merten, a Kriegsverwaltungsrat (military administration counselor) for the Nazi German occupation forces in Thessaloniki, was convicted in Greece as a war criminal and sentenced to 25 years in 1959. On November 3, 1959, Merten was granted amnesty and extradited to West Germany under political and economic pressure from West Germany, which hosted thousands of Greek migrant workers at the time. Merten's arrest also angered Queen Frederica, who had German ties and questioned the district attorney's understanding of German-Greek relations.

In Germany, Merten was eventually acquitted of all charges due to "lack of evidence." On September 28, 1960, German newspapers Hamburger Echo and Der Spiegel published excerpts of Merten's deposition to German authorities. Merten claimed that Karamanlis (then Minister for the Interior), Takos Makris, Makris's wife Doxoula (described as Karamanlis's niece), and Deputy Minister of Defense Georgios Themelis were informers in Thessaloniki during the Nazi occupation. Merten alleged that Karamanlis and Makris were rewarded for their services with a business in Thessaloniki that belonged to a Greek Jew sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. He also claimed he had pressured Karamanlis and Makris to grant him amnesty and release him from prison. Karamanlis vehemently rejected these claims as unsubstantiated and absurd, accusing Merten of attempting to extort money from him before making the statements. The West German government also denounced the accusations as calumniatory and libelous. Karamanlis accused the opposition party of instigating a smear campaign against him. Although Karamanlis never pressed charges against Merten, charges were filed in Greece against Der Spiegel by Takos and Doxoula Makris and Themelis, and the magazine was found guilty of slander in 1963. Merten did not appear to testify during the Greek court proceedings. The Merten Affair remained a central political discussion until early 1961. Historian Giannis Katris, a critic of Karamanlis, argued in 1971 that Karamanlis should have resigned and pressed charges against Merten as a private individual in German courts to fully clear his name. Nevertheless, Katris himself rejected the accusations as "unsubstantiated" and "obviously fallacious."

In 2001, former agents of the East German secret police, the Stasi, claimed to Greek investigative reporters that during the Cold War, they had orchestrated an operation of evidence falsification to damage Karamanlis's reputation by presenting him as having planned a coup. This apparent disinformation campaign allegedly centered on a falsified conversation between Karamanlis and a Bavarian officer of the King named Strauss. They also claimed that a photograph of former New Democracy leader Konstantinos Mitsotakis standing next to a uniformed Nazi officer, repeatedly published by the PASOK-leaning Greek daily Avriani, was a photomontage fabricated in Bulgaria. These disclosures have not been challenged.

4. Exile and Political Return (1963-1974)

After his resignation in June 1963, Karamanlis's National Radical Union was defeated by the Centre Union under George Papandreou in the 1963 Greek legislative election. Disappointed with the outcome, Karamanlis left Greece under the pseudonym Triantafyllides and spent the next 11 years in self-imposed exile in Paris, France. Panagiotis Kanellopoulos succeeded him as the leader of the National Radical Union.

In 1966, Constantine II of Greece sent his envoy, Demetrios Bitsios, to Paris to persuade Karamanlis to return to Greece and resume a role in politics. According to uncorroborated claims made by the former monarch in 2006 (after both Karamanlis and Bitsios had died), Karamanlis replied that he would return only if the King were to impose martial law, which was within his constitutional prerogative. Separately, US journalist Cyrus L. Sulzberger claimed that Karamanlis traveled to New York to seek US support for a coup d'état in Greece that would establish a strong conservative regime under his leadership, though Sulzberger alleged that Lauris Norstad declined to involve himself in such affairs. When the former King reiterated Sulzberger's allegations in 1997, Karamanlis stated that he "will not deal with the former king's statements because both their content and attitude are unworthy of comment." Left-leaning media, typically critical of Karamanlis, castigated the deposed King's adoption of Sulzberger's claims as "shameless" and "brazen." It is noteworthy that at the time, the former King referred exclusively to Sulzberger's account to support the theory of a planned coup by Karamanlis, making no mention of the alleged 1966 meeting with Bitsios until after both participants had died.

On April 21, 1967, constitutional order in Greece was overthrown by a military coup d'état led by officers, most notably Colonel Georgios Papadopoulos. King Constantine initially swore in the military-appointed government as the legitimate government of Greece but launched an abortive counter-coup eight months later. Following the failure of his counter-coup, Constantine and his family fled the country. Throughout his exile in France, Karamanlis remained a vocal opponent of the Regime of the Colonels, the military dictatorship that seized power.

The military junta eventually collapsed on July 23, 1974, following the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. On that day, President Phaedon Gizikis convened a meeting of veteran politicians, including Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, Spiros Markezinis, Stephanos Stephanopoulos, and Evangelos Averoff, along with the heads of the armed forces. The purpose was to appoint a national unity government that would lead the country to elections. Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, who had been the interim prime minister deposed by the dictatorship in 1967 and a vocal critic of Papadopoulos, was initially suggested to head the new interim government. However, discussions stalled. Evangelos Averoff, remaining in the meeting room after other politicians departed, insisted that Karamanlis was the only political figure capable of leading a successful transitional government, considering the internal and external circumstances and dangers. Gizikis and the military leaders, initially hesitant, were eventually convinced by Averoff's arguments, with Admiral Arapakis being the first military leader to support Karamanlis.

Following Averoff's decisive intervention, Gizikis invited Karamanlis to assume the premiership. Upon news of his impending arrival, cheering Athenian crowds took to the streets chanting, "Έρχεται! Έρχεται!He is coming! He is coming!Greek, Modern" Similar celebrations erupted across Greece, with thousands of Athenians gathering at the airport to greet him. Karamanlis was sworn in as prime minister under President pro tempore Phaedon Gizikis, who remained in power temporarily for legal continuity until a new constitution could be enacted during the Metapolitefsi period and was subsequently replaced by the duly elected President Michail Stasinopoulos.

5. Second Premiership (1974-1980)

Karamanlis's second premiership marked a critical period known as the Metapolitefsi, during which Greece transitioned from military rule to a stable parliamentary democracy.

5.1. Metapolitefsi (Restoration of Democracy)

During the inherently unstable first weeks of the Metapolitefsi, Karamanlis was forced to sleep aboard a yacht, guarded by a destroyer, due to fears of a new coup. He attempted to de-escalate tensions between Greece and Turkey, which were on the brink of war over the Cyprus crisis, through diplomatic channels. However, two successive conferences in Geneva, where the Greek government was represented by George Mavros, failed to prevent a full-scale invasion by Turkey on August 14, 1974, and the subsequent Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus. In protest, Karamanlis led Greece out of the military branch of NATO, where it remained until 1980.

The process of transitioning from military rule to a pluralist democracy proved successful under Karamanlis's leadership. During this period, he legalized the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), which had been banned since the Greek Civil War. This legalization was widely seen as a gesture of political inclusion and rapprochement. He also freed all political prisoners and pardoned all political crimes committed against the junta. Following his theme of national reconciliation, he adopted a measured approach to removing collaborators and appointees of the dictatorship from government bureaucracy. He declared that free elections would be held in November 1974, just four months after the collapse of the Regime of the Colonels.

However, Karamanlis has faced significant criticism regarding his handling of the Cyprus issue. Critics argue that in the late 1950s, he pressured Makarios III to sign the Zurich and London Agreements, threatening to withdraw Greek political support for the Greek Cypriots if he did not. Furthermore, in the summer of 1974, during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the Metapolitefsi, Karamanlis reportedly refused to send military aid to Cyprus when asked by the acting President of Cyprus, Glafcos Clerides, famously stating, "Η Κύπρος κείται μακράνCyprus lies far awayGreek, Modern." The only military aid Cyprus received from Greece during this period was in the last days of the Junta regime, through Greek commandos from A' Raider Squadron under the codename Operation Niki, which demonstrated that Cyprus was not "too far." Karamanlis also did not prosecute the armed forces chiefs who had refused to go to Cyprus's aid when Dimitrios Ioannidis had ordered them to, and he kept them in positions of charge within the armed forces, despite their alleged role in the Cypriot coup d'état against Makarios, including figures like Bonanos, Phaedon Gizikis, and Petros Arapakis. Critics contend that Karamanlis did not want to expose Western allies.

5.2. Founding of New Democracy and Election Victory

Influenced by Gaullist principles, Karamanlis founded the conservative party of New Democracy. In the 1974 elections, his party achieved a record 54.4% victory, the greatest electoral victory in modern Greek history, securing a massive parliamentary majority. He was subsequently elected prime minister.

In 1977, New Democracy again won the elections, and Karamanlis continued to serve as prime minister until 1980. The external policy of his governments, for the first time since the war, favored a multi-polar approach balancing relations between the United States, the Soviet Union, and the Third World; a policy that was continued by his successor, Andreas Papandreou.

Under Karamanlis's premiership, his government also undertook numerous nationalizations in several sectors, including banking and transportation. Karamanlis's policies of economic statism, which fostered a large state-run sector, have been described by many as socialmania.

5.3. Establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic

The 1974 elections were soon followed by a plebiscite on the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a Hellenic Republic. The referendum resulted in the formal abolition of the monarchy. This period also saw the televised Greek Junta Trials in 1975, where the former dictators received death sentences for high treason and mutiny, though these were later commuted to life incarceration. These trials sent a clear message to the armed forces that the era of immunity from unconstitutional military interventions in politics was over. The drafting of a new constitution also took place during this time.

5.4. Accession to the European Communities

Soon after his return to Greece during the Metapolitefsi, Karamanlis reactivated his push for the country's full EEC membership in 1975, citing both political and economic reasons. He was convinced that Greece's membership in the EEC would ensure political stability in a nation that had just transitioned from dictatorship to democracy.

In May 1979, he signed the full treaty of accession. Greece officially became the tenth member of the EEC on January 1, 1981, three years earlier than originally envisioned in the 1961 protocol, despite the freezing of the accession treaty during the junta years (1967-1974).

6. Presidency (1980-1985, 1990-1995)

Following his signing of the Accession Treaty with the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1979, Karamanlis relinquished the premiership. He was then elected President of the Republic by the Parliament in 1980. In 1981, he oversaw Greece's formal entry into the European Economic Community as its tenth member, a significant milestone in his vision for Greece's European destiny.

He served as president until 1985, when he resigned and was succeeded by Christos Sartzetakis. His resignation and the subsequent succession were part of what was described as "dubious processes" by Andreas Papandreou, which led to a constitutional crisis. During the 1989 political crisis, at the end of Papandreou's second term, Karamanlis famously characterized the state of affairs by stating, "Hellas has been transformed to an endless bedlam."

In 1990, he was re-elected President by a conservative parliamentary majority, serving under the conservative government of then-Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis. He served his second presidential term until 1995, when he was succeeded by Kostis Stephanopoulos.

7. Later Life and Death

Karamanlis retired from active politics in 1995 at the age of 88. His long and impactful political career included winning five parliamentary elections, serving 14 years as prime minister, and 10 years as President of the Republic, totaling more than sixty years in public service. For his extensive contributions to democracy and his pioneering role in European integration, Karamanlis was awarded the prestigious Karlspreis (Charlemagne Prize) in 1978. He bequeathed his extensive archives to the Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, a conservative think tank that he had founded and endowed.

Karamanlis died after a short illness on April 23, 1998, at the age of 91.

8. Private Life

Konstantinos Karamanlis married Amalia Megapanou Kanellopoulou (1929-2020) in 1951. Amalia was the niece of Panagiotis Kanellopoulos, a prominent politician. The couple divorced in Paris in 1972 and had no children. Karamanlis remained childless throughout his life.

9. Legacy and Assessment

Karamanlis is widely regarded as a towering figure in modern Greek politics, instrumental in shaping the nation's post-war trajectory. His legacy is characterized by significant achievements in economic development, the restoration of democratic governance, and the advancement of European integration. However, his career also faced criticisms and controversies, particularly concerning his handling of certain political events and economic policies.

9.1. Positive Contributions

Karamanlis has been widely praised for presiding over an early period of rapid economic growth in Greece from 1955 to 1963, which contributed significantly to the post-war "Greek economic miracle." He is recognized as the primary architect of Greece's successful bid for membership in the European Union, a strategic move that he believed would secure political stability and prosperity for the country. His supporters lauded him as the charismatic Ethnarches (National Leader), a title reflecting his perceived role as a guiding figure for the nation.

His most enduring positive contribution is acknowledged to be the successful restoration of democracy during the Metapolitefsi period (1974-1980). He is credited with repairing two major national schisms: first, by legalizing the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), which had been banned since the civil war, thereby fostering political inclusion and reconciliation; and second, by establishing the system of parliamentary democracy in Greece through the abolition of the monarchy and the drafting of a new constitution. His successful prosecution of the junta leaders during the Greek Junta Trials, and the heavy sentences imposed on them, sent a clear message to the armed forces that the era of immunity from unconstitutional military interventions in politics was definitively over. Furthermore, Karamanlis's unwavering policy of European integration is recognized for ending the paternalistic relationship that had existed between Greece and the United States, shifting Greece towards a more multilateral international orientation.

9.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his significant achievements, Karamanlis faced various criticisms throughout his career. Some of his left-wing opponents accused him of condoning rightist "para-statal" groups, whose members allegedly engaged in Via kai Notheia (Violence and Corruption), including fraud during electoral contests between his National Radical Union and George Papandreou's Centre Union party. These groups were also implicated in the assassination of leftist Member of Parliament Grigoris Lambrakis.

From a conservative standpoint, some critics took issue with Karamanlis's economic policies during the 1970s, which included the nationalization of Olympic Airways and Emporiki Bank and the creation of a large public sector. These policies, characterized by economic statism, were sometimes described as socialmania.

Additionally, Karamanlis has been criticized for his handling of the Cyprus problem. Ange S. Vlachos, for instance, criticized his indecisiveness in managing the Cyprus crisis in 1974, even though it is widely acknowledged that Karamanlis skillfully avoided an all-out war with Turkey at that time. More pointedly, he is criticized for having pressured Makarios III to sign the Zurich and London Agreements in the late 1950s by threatening to withdraw Greek political support for the Greek Cypriots. During the 1974 Turkish invasion, Karamanlis famously refused to send military aid to Cyprus when requested by acting President Glafcos Clerides, stating, "Cyprus lies far away." Furthermore, he faced criticism for not prosecuting the armed forces chiefs who had refused to aid Cyprus, and for retaining them in positions of authority despite their alleged roles in the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état against Makarios.

10. Tributes and Commemoration

Konstantinos Karamanlis's significant legacy has been honored through various tributes and commemorations. On June 29, 2005, an audio-visual tribute celebrating his contribution to Greek culture took place at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. The event, titled Cultural Memories, was organized by the Konstantinos G. Karamanlis Foundation, with George Remoundos as stage director and Stavros Xarhakos conducting and selecting the music. In 2007, several events were held to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth. The Konstantinos Karamanlis Foundation, a conservative think tank that he established and to which he bequeathed his archives, continues to preserve and promote his political thought and legacy.

11. See also

- History of Modern Greece

- List of presidents of Greece

- Politics of Greece

- Kostas Karamanlis

- Kostas Karamanlis (politician, born 1974)

12. Further Reading

- Clogg, Richard. Parties and Elections in Greece: The Search for Legitimacy. Duke University Press, 1987.

- Diamandouros, P. Nikiforos. "Transition to, and Consolidation of, Democratic Politics in Greece, 1974-1983: A Tentative Assessment". West European Politics 7#2 (1984): 50-71.

- Michalopoulos, Dimitri. "Konstantinos Karamanlis and the Cyprus Issue, 1955-1959". In Köse, Osman (ed.), Tarihte Kıbrıs, vol. II, pp. 1021-1028.

- Michalopoulos, Dimitri. Philia's Encomion: Greek-Turkish Relations in the 1950s. Istanbul: The Isis Press, 2018.

- Wilsford, David, ed. Political Leaders of Contemporary Western Europe: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood, 1995. pp. 217-223.

- Woodhouse, Christopher Montague. Karamanlis: The Restorer of Greek Democracy. Oxford University Press, 1982.