1. Biography

Kensaku Segoe's life was a testament to his enduring commitment to Go, from his early passion for the game to his central role in shaping its modern professional landscape and promoting it globally.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Kensaku Segoe was born on May 22, 1889, as the second son in Nomi Village, Saeki District, Hiroshima Prefecture, an area now part of Etajima City, Hiroshima Prefecture. His family was prominent, with his father serving as a prefectural assembly member. Nomi Island, where he grew up, had a long-standing tradition of strong Go players. His grandfather, a devoted Go enthusiast who had achieved 1-dan from Honinbo Shugen, introduced Segoe to the game at the tender age of five, after Segoe suffered from an eye ailment and ear problems. By the time he entered junior high school, Segoe was already playing at a level comparable to 2-dan or 3-dan players. He attended Hiroshima First Middle School, currently known as Hiroshima Prefectural Kōtaiji High School, where he was a classmate of Kaya Okinori. During the summer of 1905, while visiting his mother's hometown in Kobe, he received instruction from notable players such as Nakane Hōjirō, Abe Kamejirō, Kōhara Yoshitarō, and Hashimoto Tōzaburō, playing with handicaps ranging from three to two stones.

1.2. Early Go Career

In 1909, at the age of 20, Kensaku Segoe moved to Tokyo, accompanied by Mochizuki Keisuke, a prefectural assembly member close to his father, and joined the Hoensha. At the time, the Go world was deeply divided between the traditional Honinbo faction and the Hoensha. Mochizuki, a man of strong will, challenged Segoe, "How about you join Hoensha and defeat Honinbo?" This remark ignited Segoe's ambition. His promising performance soon gained attention. In the same year, despite being an unranked player, he participated in a youth Go tournament sponsored by the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, where he defeated Takabe Dōhei 4-dan by four points playing as Black. This game was widely publicized as "The Battle of 4-dan and No-dan." Before returning home for military service, he took a promotional test game against Suzuki Tamejirō 3-dan, winning four out of six games with a first-move handicap (sen-aitsugi). This achievement allowed him to be directly promoted to 3-dan, marking him as a "genius youth" and creating a sensation in the Go world. He also actively collaborated in the Six-Flower Society (Rokka-kai), a study group for young professional players from both the Honinbo and Hoensha factions. In 1921, Segoe advanced to 6-dan. That same year, he co-founded the Hiseikai (裨聖会) with Gankaku Junichi, Suzuki Tamejirō, and Takabe Dōhei. This new organization sought to modernize the conservative Go world by introducing progressive rules, such as the adoption of the general handicap system and time limits in games.

1.3. Founding of Nihon Ki-in

Following the devastating Great Kantō earthquake in 1923, which left the Go world even more fractured, Kensaku Segoe dedicated himself to unifying the rival factions. He actively worked to bring together the Honinbo school and the Hoensha, seeking the patronage of the prominent industrialist Okura Kihachiro. Through Segoe's tireless efforts, these factions were successfully reconciled, leading to the establishment of the Nihon Ki-in (Japan Go Association) in 1924. This achievement was pivotal, as it created a single, centralized organization for professional Go in Japan, laying the foundation for its modern development.

1.4. Pre-War Activities

In 1926, Kensaku Segoe was promoted to 7-dan by recommendation. From 1927, he took on a crucial role as the captain of the East team in the East-West Rivalry Match, a series of professional ranking tournaments (Ōteai), where he notably competed against Suzuki Tamejirō, captain of the West team. However, his career faced a significant challenge in the 1928 autumn Ōteai. In a game against Takahashi Shigeyuki, a rare and complex "thousand-year ko" (mannen-gō) arose, leading to a major dispute and a temporary suspension of the game. This controversy ultimately prevented his immediate promotion to 8-dan, as he subsequently lost to Miyasaka Keiji. The East-West Rivalry Match system was abolished that same year. Despite this setback, Segoe continued to excel, achieving second place in the fourth round of the final tournament during the inaugural Honinbo Tournament, which began in 1939. In 1942, he was officially promoted to 8-dan alongside Suzuki Tamejirō and Kato Shin. By 1944, he was also competing in the Jun-Meijin (quasi-Meijin) tournament, further solidifying his position as one of Japan's top Go players.

1.5. World War II and the Atomic Bomb Game

The final stages of World War II brought immense devastation to Japan, profoundly impacting the Go world. In 1945, the Nihon Ki-in headquarters in Tokyo was destroyed during the Tokyo air raids, resulting in the loss of invaluable Go equipment and historical records. Amidst this chaos, the third Honinbo Tournament was still underway. Due to Kensaku Segoe's persistent efforts, the second game of the championship match, between defending Honinbo Utaro Hashimoto and challenger Kaoru Iwamoto, was arranged to be held in Hiroshima in August 1945. The game took place in Yoshimi-en, Itsukaichi Town (now part of Saeki Ward), a suburb of Hiroshima. On August 6, 1945, during the course of this historic match, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima occurred. Segoe, present at the game, narrowly escaped the direct impact but was hit by the powerful blast, making him a Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor). Tragically, his third son and nephew, who had remained in the city, perished, along with all the staff of the Nihon Ki-in's Hiroshima branch. This game became infamously known as the "Atomic Bomb Game" (Genbaku Taikyoku or "Go game under the atomic bomb"). As a lasting memorial, the Go center in Seattle, constructed with funds from the Iwamoto Foundation, features a tiled wall displaying the exact board position at the moment the atomic bomb exploded.

1.6. Post-War Reconstruction and Nihon Ki-in Chairmanship

Following the end of World War II, Kensaku Segoe devoted himself entirely to the monumental task of rebuilding the devastated Japanese Go world. Collaborating closely with Kaoru Iwamoto and other key figures, he led the efforts to reconstruct the Nihon Ki-in. In 1946, a critical year for the organization, Segoe was appointed as the first chairman of the Nihon Ki-in. Under his leadership, the professional ranking tournament (Ōteai) resumed in April 1946, and the official Nihon Ki-in magazine, "Kido", was successfully relaunched. In 1948, a new Nihon Ki-in building was inaugurated in Takanawa, Minato Ward, Tokyo. However, Segoe's tenure as chairman was short-lived; he resigned in 1948 due to "misstatements" made in the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, which stemmed from an internal dispute. This incident, while leading to his resignation, did not diminish the widespread respect he commanded within the Go community, though it somewhat isolated him from direct administrative roles. In 1950, he took on a different role, becoming an auditor for Toyo Pulp, a company chaired by Kishi Nobusuke with Adachi Masashi as a director.

1.7. Later Life and Honors

Even after his resignation from the Nihon Ki-in chairmanship, Kensaku Segoe continued to be a driving force for Go's development and internationalization. He dedicated himself to compiling historical Go records, editing the 10-volume "Oshirogo-fu" (Castle Game Records from the Edo period) and "Meiji Go-fu." He also authored numerous instructional Go books, including his "Segoe Igo Kyohon" (Segoe Go Textbook), contributing significantly to Go literature. In 1952, he competed in the All Honinbo All 8-dan Tournament. In 1955, at the age of 66, he retired from professional play and was concurrently promoted to honorary 9-dan, a distinction he shared with his contemporary, Suzuki Tamejirō. His contributions were recognized with national honors: in 1958, he became the first Go player to receive the Medal with Purple Ribbon, and in 1966, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure (Second Class). In 2009, long after his passing, Kensaku Segoe was posthumously inducted into the Go Hall of Fame, solidifying his esteemed place in Go history.

2. Go Career

Kensaku Segoe's professional Go career was marked by consistent progress through the ranks and participation in significant historical matches, reflecting his dedication and skill.

2.1. Promotion History

Segoe's promotions reflect his steady ascent in the professional Go world:

- 1909: Direct promotion to 3-dan

- 1912: 4-dan

- 1917: 5-dan

- 1921: 6-dan

- 1926: 7-dan

- 1942: 8-dan

- 1955: Honorary 9-dan

2.2. Notable Games

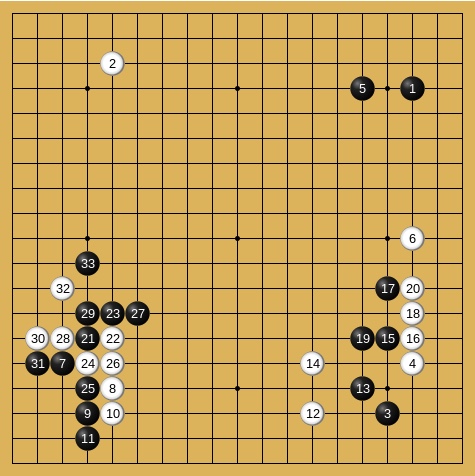

One of Kensaku Segoe's most historically significant games was against Honinbo Shusai, the then-Meijin, played on January 17 and 27, 1920. This "Approaching Shusai" match, as reported by the Yorozu Chōhō newspaper, was part of a series where Segoe and Suzuki Tamejirō from the Hoensha were challenging Shusai for the right to play with the prestigious "sen" (first move) handicap.

In this particular game, Segoe played as Black (5-dan). The opening saw White's strategy aiming to counter Black's Shusaku-style fuseki, with White's moves 8 to 12 forming a common clamping pattern. Black's moves 15 through 19 secured sente, allowing Black to play at 21 and pursue a rapid development of the fuseki. Later in the game, White's move at 24, a hane-komi (forcing move), anticipated Black's connection at 29. However, Black opted for a strong counter-attack at 27, effectively taking the initiative in the battle. Black then managed to seal off White's territory on the left side, building significant thickness in the center. While this allowed White to secure a large territory on the upper side, Black's control over the center proved decisive. The game concluded after 177 moves, with Black winning by resignation, showcasing Segoe's strategic depth and ability to control the flow of the game.

2.3. Other Records

Beyond his promotions and individual games, Segoe recorded several other notable achievements throughout his professional career:

- In the 1926 In-sha Taisen (院社対抗戦Academy vs. Company MatchJapanese), he had a record of 0-1, losing to Ono Chiyotaro.

- He won the Kō-gumi (Group A) in the second half of the 1927 Ōteai.

- In the 1960 Japan-China Go Exchange, he achieved a record of 3 wins, 1 loss, and 1 jigo (draw).

3. Publications

Kensaku Segoe was a prolific author of Go-related literature, contributing significantly to the study and education of the game. His works covered a wide range of topics, from strategic principles to comprehensive dictionaries.

His notable publications include:

- Igo Shugeki Senpō (囲碁襲撃戦法Go Attack StrategyJapanese), published by Shibunkan in 1911.

- Shōzō Kikyaku Kessenroku (少壮碁客決戦録Records of Young Go Players' Decisive BattlesJapanese), published by Hakubunkan in 1917.

- Shinshin Kikyaku Sōhasen (新進碁客争覇戦New Go Players' Championship BattlesJapanese), published by Shibunkan in 1920.

- Tesuji Jiten (手筋辞典Tesuji DictionaryJapanese), co-authored with his renowned pupil Go Seigen, published by Seibundo Shinkosha in 1971.

- Tsume-go Jiten (詰碁辞典Tsume-go DictionaryJapanese).

- Igo no Chikara o Tsuyoku Suru Hon (囲碁の力を強くする本Book to Strengthen Go SkillsJapanese).

- Oshirogo-fu (御城碁譜Castle Game RecordsJapanese), a 10-volume compilation of historical castle games from the Edo period, co-authored with Hachiman Kyōsuke and Watanabe Hideo, and distributed by the Oshirogo-fu Seiri Haifu Iinkai in 1950-51.

- Meiji Go-fu (明治碁譜Meiji Go RecordsJapanese), published by Nihon Keizai Shimbun in 1959.

- Igo Hyakunen 1 Senban Hisshō o Motomete (囲碁百年 1 先番必勝を求めて100 Years of Go 1: Seeking Certain Victory as BlackJapanese), published by Heibonsha in 1968.

- Tesuji Hayawakari (手筋早わかりQuick Understanding of TesujiJapanese).

- Son no Nai Hame-te (損のないハメ手Trick Plays Without LossJapanese).

- Go no Katachi o Oshieru Kingenshū (碁の形を教える金言集Collection of Maxims Teaching Go ShapesJapanese).

- Sakusen Jiten (作戦辞典Strategy DictionaryJapanese).

- Te no Aru Ji, Te no Nai Ji (手のある地・手のない地Territory with Moves, Territory Without MovesJapanese).

- Shōbu no Kime-te (勝負のキメ手Decisive Moves for VictoryJapanese).

His extensive bibliography underscores his commitment not only to playing Go at the highest level but also to systematically documenting and teaching its intricacies, ensuring the knowledge was passed down to future generations.

4. International Exchange and Pupil Development

Kensaku Segoe was a fervent advocate for the internationalization of Go, engaging in various international exchanges that transcended national borders. He also left an indelible mark through his role as a mentor to several of the most influential Go players of the 20th century.

In 1919, Segoe embarked on a journey to Manchuria and China, laying early groundwork for international Go ties. In 1942, he revisited China, this time accompanied by his pupil Go Seigen, at the invitation of Aoki Kazuo. His international endeavors continued post-war; in 1950, he was invited to visit the Hawaii Go Association. He served as the head of a delegation to Taiwan in 1957, further fostering regional Go connections. In 1960, he led the first delegation to China for the landmark Japan-China Go Exchange, playing a crucial role in establishing diplomatic and cultural links through Go.

Beyond his diplomatic efforts, Segoe's legacy is profoundly tied to the extraordinary talent he nurtured. He was instrumental in bringing Go Seigen to Japan in 1928, a move that would reshape the history of modern Go, and immediately took him under his tutelage. Segoe's other notable pupils include:

- Utaro Hashimoto: A formidable player and future Honinbo titleholder.

- Sugiu Masao.

- Iyo Motoichi.

- Kuji Keishi.

- Cho Hun-hyun: Who would later become a dominant force in the Korean Go world and one of the greatest players of all time.

Through these international exchanges and his profound influence on his pupils, Segoe significantly contributed to both the global spread of Go and the re-establishment of the Japanese Go world after the war.

5. Death

Kensaku Segoe passed away on July 27, 1972, at the age of 83. In the years leading up to his death, his health had progressively deteriorated, with his eyesight and hearing weakening, followed by issues with his legs and back. This decline deeply distressed him. Approximately four months after his highly esteemed pupil Cho Hun-hyun returned to South Korea to fulfill his military service, Segoe chose to take his own life.

In his suicide note, he wrote simply, "My body is unwell. There is no other way but to die." The news of his death was met with deep sorrow and a degree of bewilderment among his contemporaries, with some close associates remarking, "At that age, he didn't have to die..." His eldest son offered insight into his father's mindset, stating, "I think he believed that if he could no longer contribute to the Go world, it would be the same as exposing his corpse, so it would be better to die." His most famous pupil, Go Seigen, also reflected on Segoe's state, suggesting, "I think he became depressed because his eyesight worsened to the point where he could only play Go with amateurs." These statements highlight the profound despair Segoe felt regarding his declining physical condition and his inability to continue playing Go at the highest level, a game to which he had dedicated his entire life.

6. Assessment and Legacy

Kensaku Segoe's impact on the world of Go is multifaceted and profound, cementing his place as one of the most significant figures in the game's modern history.

6.1. Positive Contributions

Segoe is widely revered as the "father of the Nihon Ki-in" due to his indispensable role in its establishment and subsequent reconstruction. His leadership in unifying the contentious Honinbo and Hoensha factions in 1924 created a stable and centralized organization, which was foundational for professional Go in Japan. After the devastation of World War II, he tirelessly led the efforts to rebuild the Nihon Ki-in, serving as its first chairman and spearheading the resumption of critical professional activities and publications.

Beyond his administrative acumen, Segoe was a fervent champion of Go's internationalization. His numerous trips to China, Manchuria, Hawaii, and Taiwan, and his leadership in the first Japan-China Go Exchange delegation, were pioneering efforts that broadened Go's reach beyond Japan and fostered crucial cultural exchanges.

Perhaps his most enduring legacy lies in his extraordinary ability to identify and cultivate talent. As a mentor, he guided and shaped the careers of several legendary Go players, most notably Go Seigen, whom he was instrumental in bringing to Japan, and Cho Hun-hyun, a key figure in the rise of Korean Go. His pupils, including Utaro Hashimoto, went on to achieve immense success, profoundly influencing the global landscape of the game. Furthermore, his extensive body of instructional literature played a vital role in formalizing Go study and popularizing the game among new generations of enthusiasts.

6.2. Criticisms and Controversies

While Kensaku Segoe's career was largely marked by positive contributions, it was not without its challenges and controversies. One notable incident occurred during the 1928 autumn Ōteai, where a complex "thousand-year ko" (mannen-gō) in his game against Takahashi Shigeyuki led to a prolonged dispute. This highly unusual situation, which resulted in the game being temporarily suspended, ultimately contributed to his failure to achieve an immediate promotion to 8-dan.

Another significant controversy involved his resignation as the first chairman of the Nihon Ki-in in 1948. This decision was precipitated by "misstatements" made in the Yomiuri Shimbun, which arose from an internal quarrel within the organization. While the exact details of the "internal quarrel" are not fully documented in public records, it led to Segoe stepping down from a leadership position he had worked so hard to establish and rebuild. Although he remained highly respected, this event marked a period of isolation from direct administrative roles within the Nihon Ki-in.

6.3. Impact on the Go World

Kensaku Segoe's impact on the development of modern Go is immeasurable. His foundational role in establishing the unified Nihon Ki-in was critical in transforming Go from a fragmented collection of schools into a structured, professional sport. This unification provided a stable platform for tournaments, professional rankings, and the systematic popularization of the game across Japan.

He significantly contributed to Go's popularization through his accessible instructional books and his tireless efforts in promoting the game at all levels. The educational systems he helped to establish, through his publications and his work within the Nihon Ki-in, laid the groundwork for future generations of Go players to learn and improve. His pioneering work in international exchange also fostered the global growth of Go, paving the way for the game's spread beyond East Asia. Segoe's vision for Go extended beyond national borders, influencing its progression into a globally recognized intellectual sport.

6.4. Memorials

Kensaku Segoe's enduring legacy is commemorated in various ways. In 1983, a bronze statue, created by the renowned sculptor Enomura Katsuzō, was erected in his honor and donated to his hometown of Nomi Island (now Etajima City), where it stands as a tribute to his early life and enduring connection to the region. In 2009, his profound contributions to the game were further recognized when he was posthumously inducted into the Go Hall of Fame, solidifying his status as a titan of the Go world.