1. Etymology and Nomenclature

The goddess was originally known as Xuannü (玄女Chinese). The name has been translated into English as the "Dark Lady" or "Mysterious Lady," reflecting the profound and enigmatic nature associated with her. The character for xuan (玄) can also denote the color black. During the late Tang dynasty, the esteemed Daoist master Du Guangting (850-933) expanded her title to Jiutian Xuannü (九天玄女Chinese), adding Jiutian (九天), which means "[of the] Nine Heavens."

Jiutian Xuannü is considered a divine sister to Sunü (素女Chinese). Together, their names form the term xuansu zhidao (玄素之道Chinese), which is associated with the Daoist arts of the bedchamber. In various regions and languages, she is also known by names such as Giu Tiang Hiang Nu (Hokkien), Giu Tiang Hiang Neung (Teochew), Jiu Tian Xuan Nü (Mandarin), or colloquially as Jiutian Xuannü Niangniang (九天玄女娘娘Chinese), Jiutian Xuanmu (九天玄姆Chinese), or Jiutian Niangniang (九天娘娘Chinese). In Vietnam, she is referred to as Cửu Thiên Huyền Nữ.

2. Mythological Origins and Early Traditions

Jiutian Xuannü's mythological background and early traditions reveal her as a powerful and mysterious entity, deeply intertwined with both primeval Chinese myths and the developing Daoist cosmology.

2.1. Early Depictions and Divine Status

Early depictions of Jiutian Xuannü portrayed her in a transcendental and enigmatic form, specifically with a human head and a bird body. This avian association links her to the Xuan Niao (玄鳥Chinese, "Black Bird" or "Dark Bird"), a mythical swallow that, according to ancient Chinese texts like the Shijing, was believed to have laid an egg consumed by Jiandi, the mother of Qi, the legendary ancestor of the Shang dynasty. This connection suggests a primordial role in the origins of Chinese civilization and royal lineage. Similarly, the granddaughter of Zhuanxu, Nüxiu, was said to have given birth to Daye after consuming a Xuan Niao egg.

Within the Daoist pantheon, Jiutian Xuannü holds a significant position, often described as being second only to the Xi Wangmu (西王母Chinese) in status, and sometimes even identified with Shangyuan Furen (上元夫人Chinese). She is considered Huangdi's teacher and Xi Wangmu's disciple, acting as a celestial protectress and aide to heroes. As a spirit embodying the essence of heaven and earth and the spiritual manifestation of yin and yang, she is said to possess all knowledge and is regarded as a primary deity in Daoism, holding the esteemed rank of chief among all immortals.

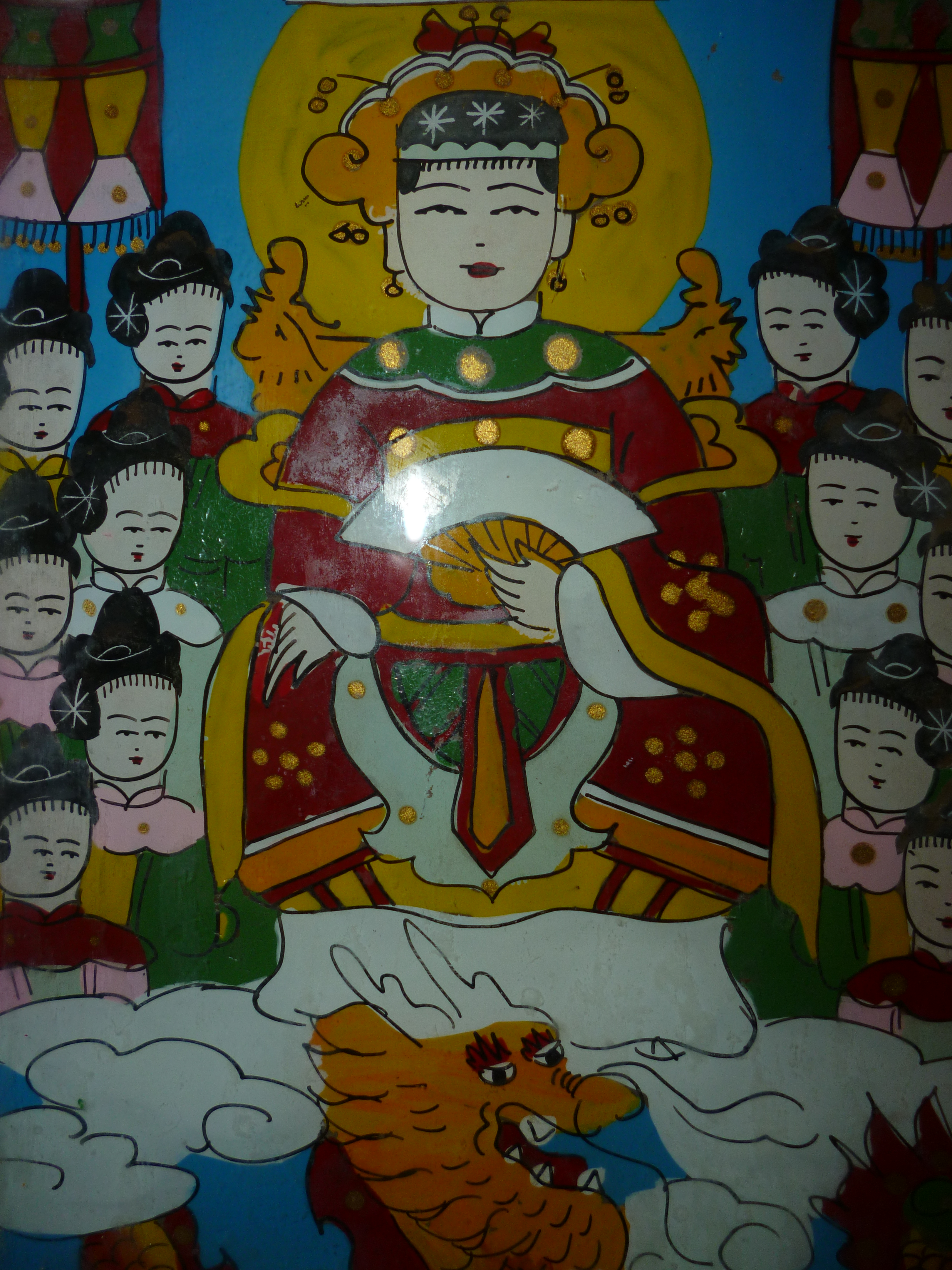

Her appearance is often grand and ethereal: she is depicted riding a cinnabar phoenix, guiding it with phosphors and clouds as reins, and adorned in variegated kingfisher-feather garments of nine colors, sometimes complemented by black fox fur. According to the Taishang Laojun Zhongjing, she is described as wearing the white of Venus and brilliant stars, with a "pearl of Great Brilliance" illuminating her entire body, which is believed to grant longevity. Her birthday is celebrated on the 15th day of the second lunar month.

2.2. Relationship with the Yellow Emperor

A pivotal narrative in Chinese mythology details Jiutian Xuannü's crucial assistance to the Huangdi (黃帝Chinese) during his legendary conflict with Chiyou (蚩尤Chinese). Chiyou, depicted as a formidable adversary with eighty brothers possessing beastly bodies, human speech, and heads of bronze with iron foreheads, wreaked havoc, consuming sand and rocks, and fabricating powerful weapons that terrorized the world. In one critical moment, Chiyou conjured a dense, impenetrable mist that obscured day and night, disorienting Huangdi's forces and leaving him in distress for days.

In response to Huangdi's plight, Jiutian Xuannü appeared, riding a cinnabar phoenix into the mist, her presence luminous and majestic. She declared that her teachings were based on the "Grand Supreme" and offered her wisdom to Huangdi. When Huangdi expressed his desire for strategies to achieve "a myriad victories in a myriad battles" to alleviate the suffering of his people, the goddess bestowed upon him a collection of mystical objects and military treatises. These included:

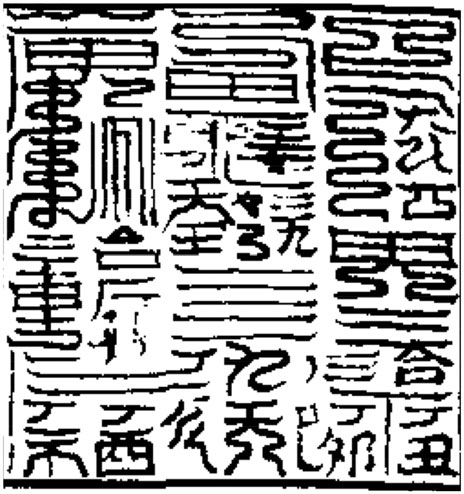

- The Talismans of the Martial Tokens of the Six Jia Cyclicals and the Six Ren Cyclicals (六甲六壬兵信之符Chinese)

- The Book by which the Five Emperors of the Numinous Treasure Force Ghosts and Spirits into Service (靈寶五帝策使鬼神之書Chinese)

- The Seal of the Five Bright-Shiners for Regulating Demons and Communicating with Spirits (制妖通靈五明之印Chinese)

- The Formula of the Five Yin and Five Yang for Concealing the Jia Cyclicals (五陰五陽遁[甲]之式Chinese)

- Charts for Grabbing the Mechanism of Victory and Defeat of the Grand Unity from the Ten Essences and Four Spirits (太一十精四神勝負握機之圖Chinese)

- Charts of the Five Marchmounts and the Four Holy Rivers (五[嶽]河圖Chinese)

- Instructions in the Essentials of Divining Slips (策精之訣Chinese)

- Instructions for creating the South-pointing Chariot (指南車), a device crucial for navigation during the mist.

Equipped with these divine gifts, Huangdi was able to overcome Chiyou and subsequently ascend to heaven. Jiutian Xuannü's assistance extended beyond warfare; she is also credited with aiding Huangdi in peacetime endeavors, such as teaching his concubine how to raise silkworms for silk production, instructing Rongcheng in observing celestial phenomena, and assisting Cangjie in the invention of Chinese characters. She also transmitted knowledge of the Qimen Dunjia (奇門遁甲Chinese) and the 64 hexagrams of the I Ching, vital for divination and strategy.

3. Major Roles and Abilities

Jiutian Xuannü's divine influence spans a wide array of domains, reflecting her multifaceted nature and critical importance in Chinese spiritual traditions.

3.1. Warfare and Military Strategy

Jiutian Xuannü is preeminently known as a goddess of war and military strategy. Her association with warfare is detailed in ancient texts like the Longyu Hetu (龍魚河圖Chinese, "Chart of the River of the Dragon-Fish"), presumed to be from the Xin dynasty, which recounts her manifestation to Huangdi during his conflict with Chiyou to bestow military guidance. Her intervention in warfare is a recurring theme in Daoist texts, particularly those found in the Zhongshu Bu (眾術部Chinese, "The Section of Miscellaneous Magic") of the Daozang (道藏Chinese, "Daoist Canon"). These texts affirm that Heaven dispatched her to deliver "military messages and sacred talismans" to the Yellow Emperor, enabling him to subdue his enemies. Historical figures, such as the Tang dynasty general Li Jing, are also said to have employed her military strategies.

A significant aspect of her martial abilities involves powerful magical capabilities, particularly the skill of invisibility (隱身Chinese) and the method of mobilizing the stars of the Northern Dipper (北斗Chinese) to protect the state. The Lingbao Liuding Mifa (靈寶六丁秘法Chinese, "Secret Lingbao Method Concerning the Spirits of the Six Ding Days") explicitly states the martial origin of Jiutian Xuannü's magic. She exercises her power through her acolytes, the Six Ding Jade Maidens (六丁玉女Chinese), each responsible for concealing a specific aspect of an individual:

- The Jade Maiden of Dingmao (丁卯玉女Chinese) conceals the physical body.

- The Jade Maiden of Dingsi (丁巳玉女Chinese) conceals one's destiny.

- The Jade Maiden of Dinghai (丁亥玉女Chinese) conceals one's fortune.

- The Jade Maiden of Dingyou (丁酉玉女Chinese) conceals one's hun soul.

- The Jade Maiden of Dingwei (丁未玉女Chinese) conceals one's po soul.

- The Jade Maiden of Dingchou (丁丑玉女Chinese) conceals one's spirit.

Achieving invisibility is considered a crucial military strategy for defeating enemies and safeguarding the state, emphasizing the belief that one must first learn self-concealment to expel evil and restore righteousness. The goddess and her six maidens collectively represent the yin force in the universe, which is the conduit for physical concealment, thus intertwining their magic with their femininity.

Further magical associations appear in the Micang Tongxuan Bianhua Liuyin Dongwei Dunjia Zhenjing (秘藏通玄變化六陰洞微遁甲真經Chinese, "Book of the Six Yin of the Sublime Grotto, Veritable Scripture of the Hidden Days"), from the early Northern Song dynasty. This text provides an incantation linked to Jiutian Xuannü, claiming that by reciting it and performing the Paces of Yu (禹步Chinese), one could achieve invisibility. In Ge Hong's Baopuzi (抱朴子Chinese, "Book of the Master Who Embraces Simplicity"), the Paces of Yu are described as components of the divinatory system of dunjia (遁甲Chinese, "Hidden Stem"). This system allowed for calculating the immediate position of the six ding spirits in the space-time continuum. The six ding are the spirits governing the "irregular gate" (奇門Chinese), a perceived rift in the universe. Approaching this gate through the Paces of Yu grants entry to the emptiness of the otherworld, where one can become invisible to harmful influences.

Additionally, the Beidou Zhifa Wuwei Jing (北斗治法武威經Chinese, "The Scripture of Martial Power, of the Method of Government of the Northern Dipper") states that Jiutian Xuannü taught the method to mobilize the stars of the Northern Dipper to Yuan Qing (遠清Chinese), an official during the Sui-Tang transition. This method, known as Beidou Shi'er Xing (北斗十二星Chinese, "Twelve Stars of the Northern Dipper"), is accompanied by an incantation called Tiangang Shenzhou (天罡神咒Chinese, "Incantation of the Heavenly Mainstay"), as detailed in the Shangqing Tianxin Zhengfa (上清天心正法Chinese, "Correct Method of the Heart of Heaven, of the Shangqing Tradition") from the Southern Song period. She is also associated with the divinatory system of Liuren Shenke (六壬神課).

3.2. Longevity and Alchemy

Jiutian Xuannü plays a significant role in Daoist practices aimed at achieving longevity and immortality. She appears in several works of physiological microcosmology, where the human body is viewed as a microcosm of the universe, and deities are believed to reside within. These texts typically position Jiutian Xuannü along the central median of the body and associate her with the circulation of vital breath, which is essential for nourishing the spirit and extending life.

In the Huangting Jing (黃庭經Chinese, "Classic of the Yellow Courtyard"), adepts are instructed to send their breath down to enter the goddess's mouth, a practice believed to promote vital energy. The Taishang Laojun Zhongjing (太上老君中經Chinese, "Central Classic of Lord Lao from the Supreme Realm"), likely dating to the 5th century, describes her as residing "between the kidneys, dressed only in the white of Venus and the brilliant stars." Her "pearl of Great Brilliance" is said to illuminate the adept's entire body internally, thereby enabling them to prolong their life and escape death.

In the Laozi Zhongjing (老子中經Chinese, "Central Classic of Laozi"), Jiutian Xuannü is depicted as one of three deities seated upon divine tortoises. The text proclaims her as "the mother of the Way of the void and nothingness" and provides instructions for adepts to meditate on a white breath between their shoulders, visualizing a white tortoise with the Mysterious Woman atop it. Adepts are also taught to summon two governors beside her, the "Governor of Destiny and Governor of the Registers," to petition for their names to be removed from the death list and inscribed onto the "Life List of the Jade Calendar," thereby promising a long life.

Since the 3rd century AD, Jiutian Xuannü has also been closely associated with Chinese alchemy. Ge Hong's Baopuzi notes her role in assisting other deities in preparing elixirs and mentions that adepts erected altars to her when creating metal elixirs. The text also records her discussions with Huangdi regarding calisthenics and diet, further linking her to practices for physical and spiritual well-being. During the Song dynasty, her connection to neidan (inner alchemy) became particularly prominent.

3.3. Sexuality and Bedchamber Arts

While many texts bearing Jiutian Xuannü's name pertain to warfare, a distinct body of literature focuses on her connection to sexuality and the "bedchamber arts" (Fangzhongshu). The Xuannü Jing (玄女經Chinese, "Mysterious Woman Classic") and the Sunü Jing (素女經Chinese, "Natural Woman Classic"), both originating from the Han dynasty, were influential handbooks presented in a dialogue format, offering guidance on sexual practices. Parts of the Xuannü Jing were later incorporated into the Sui dynasty edition of the Sunü Jing. These handbooks were widely known among the upper classes from the Han dynasty onwards, although figures like Wang Chong criticized the sexual arts as "not only harming the body but infringing upon the nature of man and woman."

During the Tang dynasty and earlier periods, Jiutian Xuannü was frequently associated with these sexual arts, with the Xuannü Jing remaining a familiar work among literati. The Dongxuanzi Fangzhong Shu (洞玄子房中術Chinese, "Bedchamber Arts of the Master of the Grotto Mysteries"), likely authored by the 7th-century poet Liu Zongyuan, contains explicit descriptions of sexual techniques purportedly transmitted by Jiutian Xuannü.

These sexual practices, supposedly taught by Jiutian Xuannü, were often equated with alchemy and physiological procedures for extending life. In Ge Hong's Baopuzi, Jiutian Xuannü is quoted telling Huangdi that sexual techniques are akin to "the intermingling of water and fire-it can kill or bring new life depending upon whether or not one uses the correct methods." This highlights the Daoist view of sexual cultivation as a means to achieve balance and vitality.

3.4. Other Associations

Beyond her primary roles in warfare, longevity, and sexuality, Jiutian Xuannü holds several other significant associations, reflecting her diverse influence in popular belief and regional worship. In contemporary times, she is venerated as a patron of marriage and fertility. Some beliefs even attribute to her the origin of the traditional Chinese custom that prohibits marriage between individuals sharing the same surname.

In Vietnam, particularly in regions such as Hue and Hoi An, Jiutian Xuannü is also revered as a patron deity for various craftsmen, especially carpentry. She is considered a "savior mother goddess" for women and is believed to offer protection and guidance for one's personal destiny. These regional characteristics underscore her varied cultural significance and her role as a benevolent protector in different professional and social contexts. She also has the power to suppress and exorcise evil spirits, with some traditions suggesting that drawing a bow and arrow image on the courtyard on Tet can ward off malevolent forces.

4. Development of Divine Status and Worship

The divine status of Jiutian Xuannü has undergone significant evolution, transitioning from ancient folk reverence to formalized integration into the Daoist pantheon and widespread worship.

4.1. Incorporation into Daoism and Image Transformation

The active worship of Jiutian Xuannü by the ancient Chinese gradually diminished after the Han dynasty, but over subsequent centuries, she was progressively assimilated into Daoist traditions. During the Tang dynasty, various perceptions of Jiutian Xuannü coexisted. However, the burgeoning influence of Daoism facilitated the emergence of a new image for her: that of a high goddess of war who achieved victory through magical and intellectual means, and who also transmitted the arts of immortality. In this transformation, her aspects related to sexuality, military conquest, and eternal life were reinterpreted and refined to align with this new, elevated portrayal.

Notably, the Daoist master Du Guangting played a crucial role in this process. He actively sought to purge "heterodox and crude elements" from Jiutian Xuannü's popular legends, including her erotic and sexually-empowering attributes. His efforts aimed to re-establish her as a martial goddess, suitable for the revered Shangqing School of Daoism, thus solidifying her place within the formalized Daoist religious structure.

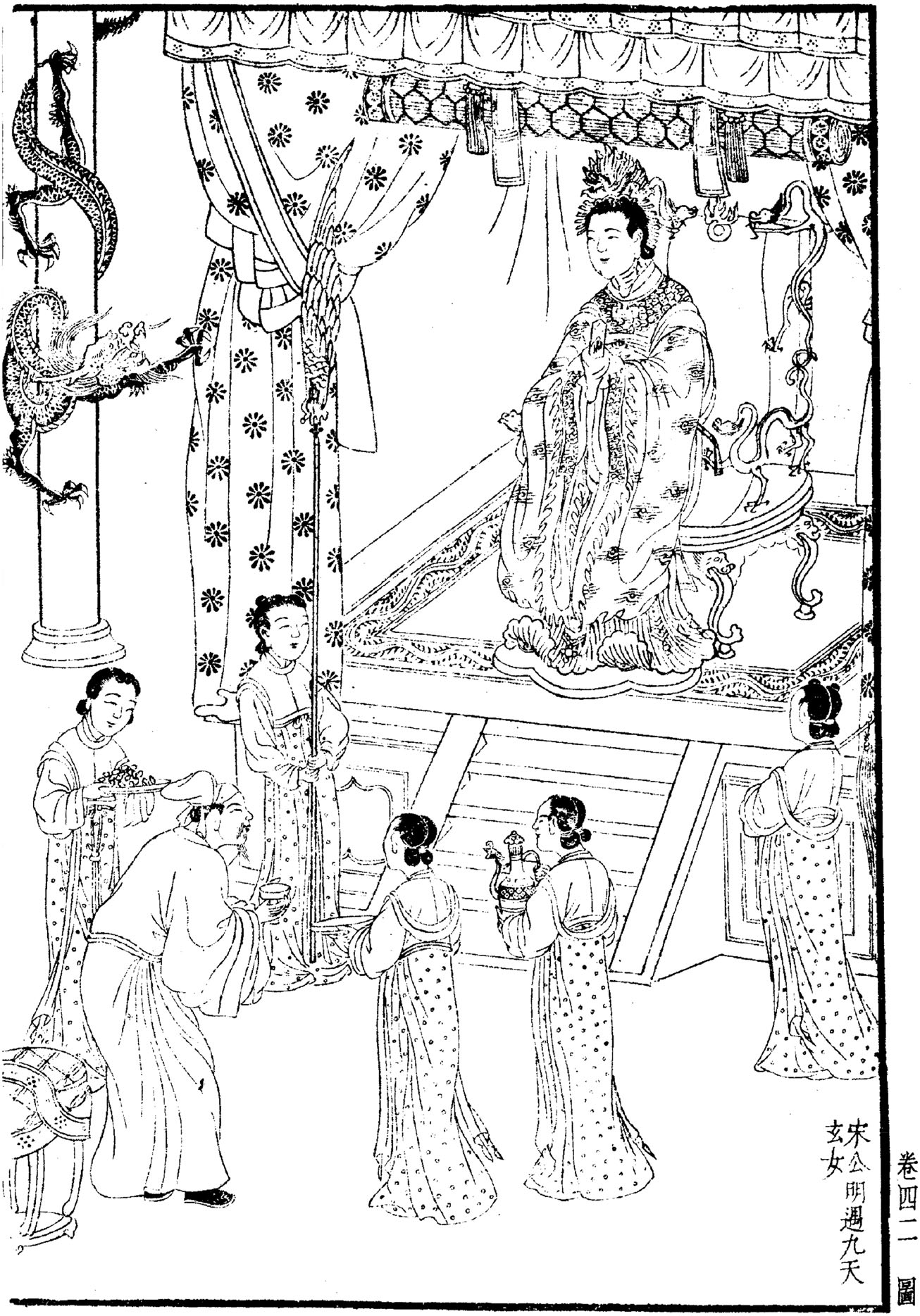

4.2. Official Veneration during the Ming Dynasty

By the Ming dynasty, Jiutian Xuannü had attained official recognition as a celestial protectress and was venerated as a tutelary goddess of the state. This elevation was prominently demonstrated in 1493 when Empress Zhang (1470-1541), wife of the Hongzhi Emperor, underwent an ordination ceremony. Her ordination was certified in a scroll titled The Ordination of Empress Zhang, which, although not depicting Jiutian Xuannü directly, included an inscription by the Daoist master Zhang Xuanqing (張玄慶Chinese, died 1509) of the Zhengyi Dao school. This inscription accorded Jiutian Xuannü a preeminent position above all other celestial warriors, listing her ahead of divine categories such as Generals, Marshals, Heavenly Soldiers, the Six Ding Jade Maidens, and the Six Jia Generals.

Furthermore, she was granted an expanded official title: Jiutian Zhanxie Huzheng Xuannü (九天斬邪護正玄女Chinese, "Dark Lady of the Nine Heavens who Slays Evil and Protects Righteousness"). The Lingbao Liuding Mifa links the phrase "slaying evil and protecting righteousness" (斬邪護正Chinese) directly to the goddess, emphasizing that "in order to slay evil and return to righteousness, one first needs to know how to become invisible" (斬邪歸正,先須知隱形Chinese), tying her expanded title to her unique martial abilities.

The heightened veneration and elevation of Jiutian Xuannü during this period likely had an underlying political rationale. It served to bolster the aristocratic Zhang family's standing over other rival factions, such as the Zhou family (of Empress Dowager Zhou, grandmother of the Hongzhi Emperor), who adhered to Buddhism. The relationship between Empress Zhang and Jiutian Xuannü paralleled the Ming emperors' veneration of Xuanwu, another significant Daoist deity, thereby promoting the empress and her family's position within the imperial court. Her association as a fertility goddess may also have contributed to Empress Zhang's devotion to her.

4.3. Contemporary Worship and Regional Characteristics

Contemporary worship of Jiutian Xuannü continues to flourish in various forms across China and Southeast Asia, characterized by distinct religious practices and regional customs.

4.3.1. Worship in China

In China, Jiutian Xuannü continues to be widely revered. She is considered a patron of marriage and fertility, and some believers attribute to her the traditional Chinese custom of prohibiting marriage between individuals of the same surname. Her temples, known as Dao Guan (Daoist temples), can be found in various locations.

She is also popular among Hokkien-speaking communities, particularly in southern Thailand, and to a lesser extent among Teochew-speaking communities. This widespread veneration highlights her enduring significance in Chinese folk religion and Daoist practices.

4.3.2. Worship in Vietnam

The worship of Jiutian Xuannü in Vietnam dates back to the Lý dynasty. During the Nguyễn dynasty, the imperial court officially recognized her, granting her the title "Dực bảo Trung hưng Huyền nữ." This veneration is widespread in various regions of Vietnam, including Huế, the Northern region, and the Southern region. She is often honored as a leading goddess, frequently worshipped alongside other significant female deities such as Thiên Y A Na, Diễn Ngọc Phi, Đại Càn Tứ Vị thánh nương, and Thánh Mẫu Liễu Hạnh.

In Huế, Jiutian Xuannü is revered by both the imperial court and the common people. She is considered a personal destiny god (bổn mạng) and the patron deity of carpenters, reflecting her association with specific professions. In Hội An, local communities worship Jiutian Xuannü at village communal houses like those in Cẩm Phô and Sơn Phong. Here, she is also recognized as a patron deity of handicrafts and a "savior mother goddess" for women. According to scholar Huynh Ngoc Trang, "Cửu Thiên Huyền Nữ also saves women, and is the ancestor of handicraft trades. Cửu Thiên Huyền Nữ is worshipped in temples outside the communal house or in the main hall of the communal house."

In Hưng Yên, the Den Cuu Thien Huyen Nu temple, established around the late 17th century, is dedicated to her. She is honored as a Thành hoàng (village guardian deity) for her perceived role in assisting people during times of hardship and danger. Annually, on the 9th day of the 9th lunar month, the temple hosts a traditional festival in her honor, featuring various cultural activities such as rituals, incense offerings, and artistic performances. The presence of Jiutian Xuannü's worship in Vietnam underscores the intricate cultural exchange and acculturation between China and Vietnam throughout history, enriching the local system of god and goddess worship with unique characteristics.

5. Descriptions and Appearance

Jiutian Xuannü's appearance is described with varying details across different texts, highlighting her celestial and often awe-inspiring nature.

In the Taishang Laojun Zhongjing, she is depicted as being dressed only in the pure white of Venus and surrounded by brilliant stars, with a "pearl of Great Brilliance" that shines to illuminate everything. When she appeared before Huangdi, as narrated in the Yongcheng Jixian Lu, she was adorned in variegated kingfisher-feather garments of nine colors and rode a cinnabar phoenix, guiding it with phosphors and clouds as reins. Earlier traditions also portray her with a human head and a bird body, linking her to the mythical Xuan Niao.

A vivid poetic description of Jiutian Xuannü's physical appearance appears in the Rongyu Tang edition of the Ming dynasty novel Water Margin:

"On her head, she has a nine-dragon and flying phoenix topknot, and on her body she wears a red silken gown decorated with golden thread; blue jade-like strips run down the long gown and a white jade ritual object rises above her colored sleeves. Her face is like a lotus calyx and her eyebrows fit naturally with her hair. Her lips are like cherries, and her snow-white body appears elegant and relaxed. She appears to be the Queen Mother who hosts a saturn peach banquet, but she also looks like Chang'e who resides in the moon palace. Her gorgeous immortal face cannot be depicted, nor can the image of her majestic body."

This description emphasizes her regal attire, ethereal beauty, and divine presence, comparing her to other revered celestial figures.

6. Appearances in Literature and Popular Culture

Jiutian Xuannü's influence extends deeply into Chinese classical literature and continues to resonate in modern popular culture, where she is frequently portrayed as a powerful and mystical figure.

6.1. Classical Novels

Jiutian Xuannü makes notable appearances in several prominent Chinese classical novels, often as a divine benefactor who bestows mystical abilities or critical advice upon protagonists.

In Water Margin, she is a deity whom the protagonist Song Jiang encounters on two separate occasions. During his escape from soldiers, he seeks shelter in a temple and meets the goddess, who presents him with a set of three divine books. These texts are intended to aid him in his mission to "deliver justice on Heaven's behalf." In a later instance, she appears to him in a dream while he is leading the Liangshan forces against Liao invaders, teaching him how to break the enemy's battle formation.

In The Three Sui Quash the Demons' Revolt (also known as Ping Yao Zhuan), Xuannü plays a significant role in the story of Yuan Gong (袁公Chinese), a white interconnected-arm gibbon renowned for his martial arts, Daoist knowledge, and apparent immortality. She escorts Yuan Gong to heaven, where he is entrusted with guarding heavenly books, though forbidden from browsing them. His curiosity leads him to open a secret box, releasing Heaven's Teachings to earth, which subsequently causes a series of disasters culminating in Wang Ze's rebellion in the 1040s. Yuan Gong eventually redeems himself through his role in quelling the revolt and is restored to his former position as Lord of White Cloud Cave. This novel is notable as it is believed that the character of Jiutian Xuannü replaced an earlier figure named Sheng Gugugu in later adaptations.

She also appears in Dongyou Ji (The Eight Immortals Eastward Journey) and Dang Kou Zhi (The Ravaging of the Bandits). In Tongsu Daming Nüxian Zhuan (also known as Nüxian Waishi), the female protagonist Tang Saier gains her formidable illusory powers after studying seven volumes of heavenly books bestowed upon her by Jiutian Xuannü, which she uses to manipulate the Yan army. In this work, Jiutian Xuannü is depicted as the chief of celestial immortals who govern the sword immortals, with Sunü identified as her sister, and she refers to herself using the imperial "zhen" (朕Chinese).

6.2. Modern Popular Culture

Jiutian Xuannü continues to be a recurring figure in contemporary media, reflecting her enduring popularity and adaptable nature. She has been featured in several films and television series, including the 2007 Hong Kong film It's a Wonderful Life, the 1980s Chinese television series Outlaws of the Marsh, and the 1985 Hong Kong television series The Yang's Saga. In the realm of video games, she appears in the mobile game Tower of Saviors and is a character in the popular The Legend of Sword and Fairy 4 and The Legend of Sword and Fairy 7 series.