1. Early Life and Education

Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne's formative years were shaped by his family's legal background and a unique educational experience that fostered his early intellectual and political views, laying the groundwork for his later revolutionary engagement.

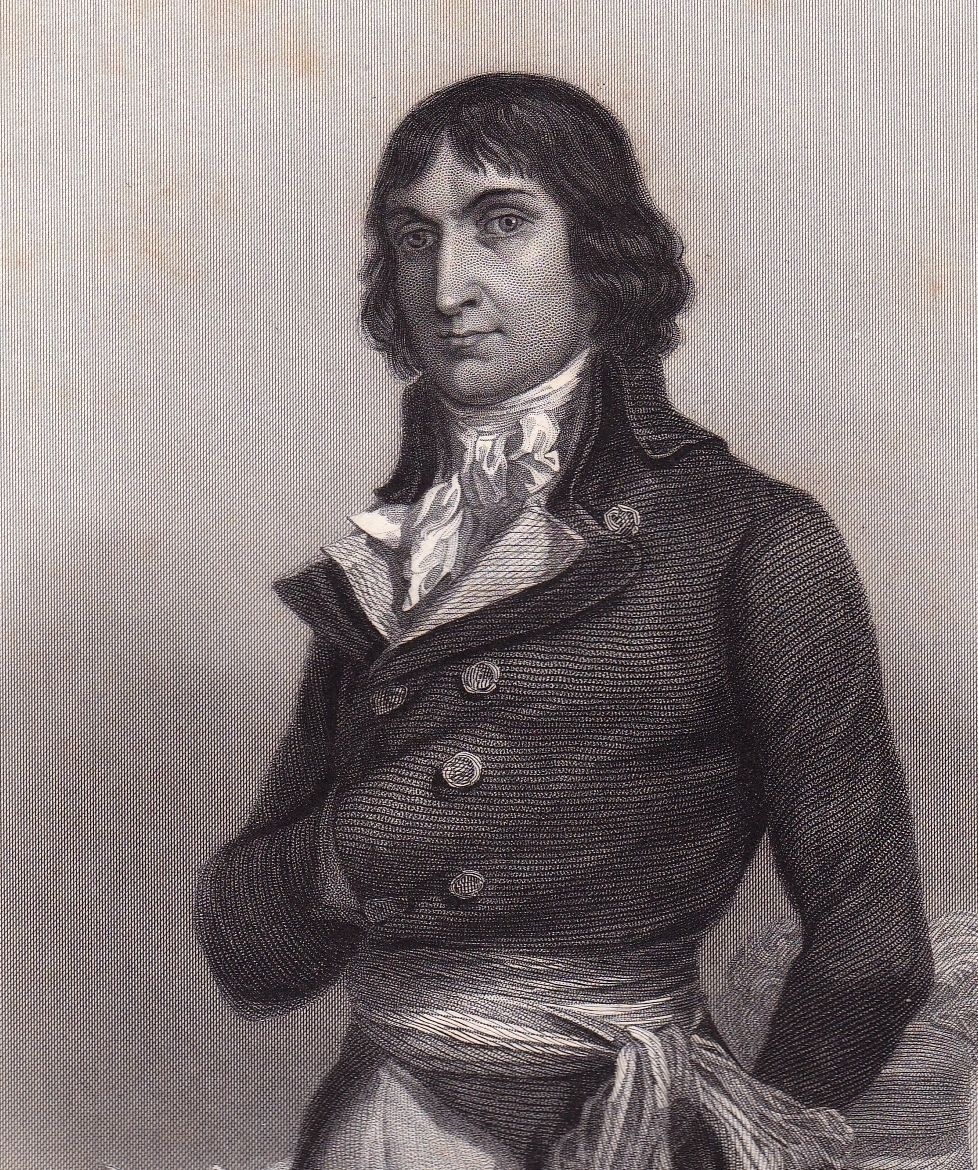

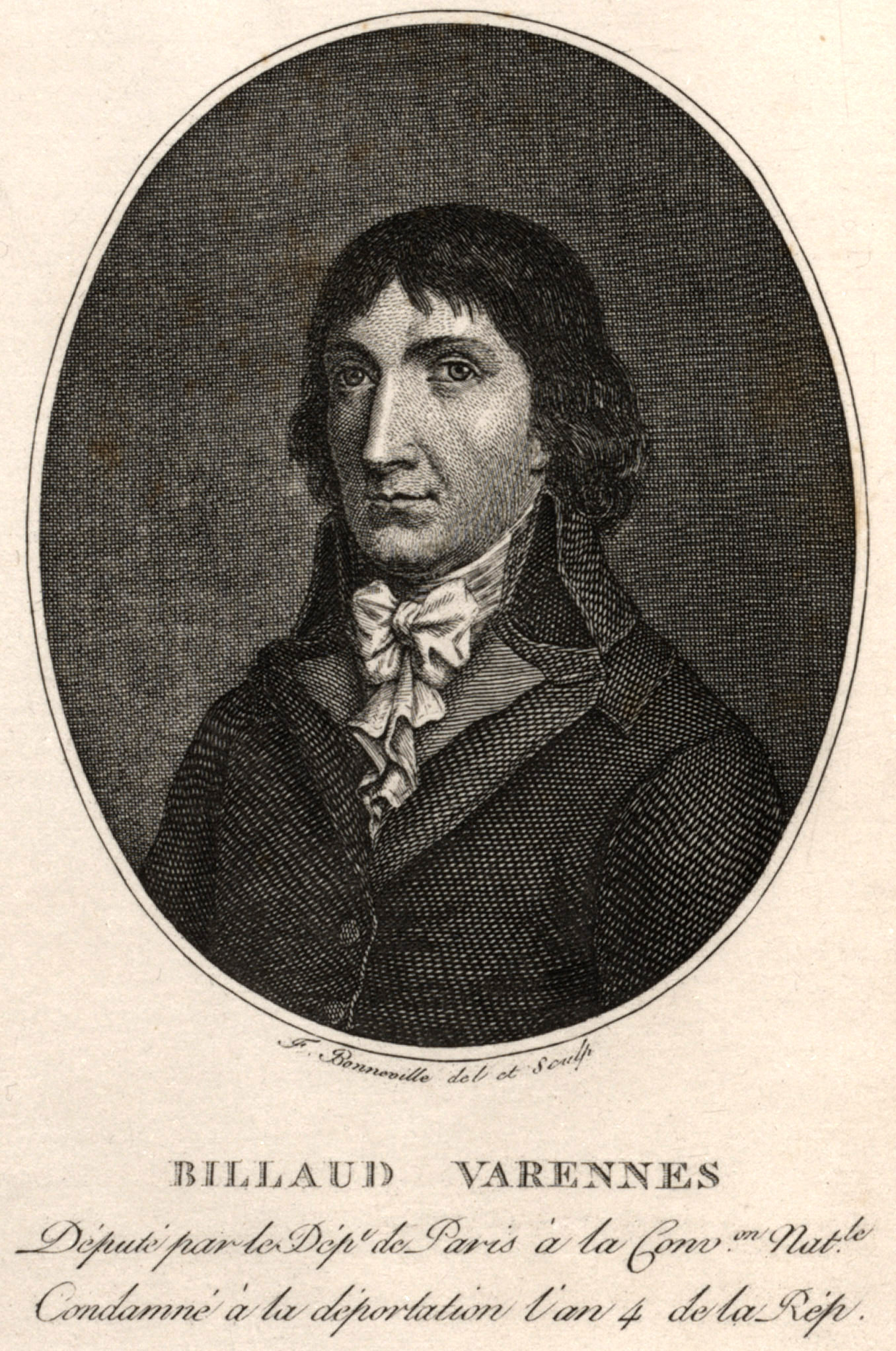

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Billaud-Varenne was born in La Rochelle, France, on 23 April 1756. He came from a family deeply rooted in the legal profession; both his grandfather and father were lawyers to the Parlement of Paris. As the first son in his direct family line, Billaud-Varenne was assured a solid education and the opportunity to pursue the same esteemed profession.

1.2. Education

His academic journey began at the college in Niort, which was run by the French Oratorians. He continued his studies, taking philosophy at La Rochelle. His education at Niort was particularly influential in shaping his character, as the teaching methods there were unconventional for the revolutionary era, emphasizing modernity and tolerance. Billaud-Varenne also attended another Oratory of Jesus school, the Collège de Juilly, where he served as a prefect of studies. He later became a professor at Juilly, a position he took up when he grew dissatisfied with the practice of law. He remained there for a short period until the publication of a comédiecomedyFrench strained his relationship with the school's administration, compelling him to leave in 1785.

1.3. Legal and Literary Career

After his departure from Juilly, Billaud-Varenne moved to Paris, where he married and acquired a position as a lawyer in the parlement. In 1786, he married the daughter of a tax collector and subsequently added "Varenne" to his name. In early 1789, prior to the outbreak of the French Revolution, he published a three-volume work in Amsterdam titled Despotisme des ministres de la FranceDespotism of the ministers of FranceFrench, which combatted ministerial despotism by asserting the rights of the nation, fundamental laws, and ordinances. Around the same time, he also released a well-received anti-clerical text called "The Last Blow Against Prejudice and Superstition." These early writings foreshadowed his deep engagement with revolutionary principles. Regarding the Church, he famously stated in this text: "However painful an amputation may be, when a member is gangrened it must be sacrificed if we wish to save the body."

2. Revolutionary Activities

Billaud-Varenne's active participation and leadership were central to the French Revolution, from his radical activism in its early stages to his crucial role in the most critical periods of revolutionary government, including the Reign of Terror.

2.1. Early Activism and Jacobin Club

As events in France moved closer to Bastille Day, Billaud-Varenne enthusiastically adopted the principles of the French Revolution. He joined the Jacobin Club in 1790, quickly becoming one of its most outspoken and violent anti-Royalist orators. He forged a close alliance with Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois. Following the Flight to Varennes by Louis XVI, Billaud-Varenne published a pamphlet titled L'Acéphocratiemeaning 'power without head'French, in which he explicitly called for the establishment of a federal republic.

On 1 July, during another speech at the Jacobin Club, he once again advocated for a republic, a proposition initially met with derision from supporters of the constitutional monarchy. However, when he reiterated his demand for a republic two weeks later, the speech was printed and widely distributed to Jacobin branch societies across France, spreading his radical ideas. On the night of 10 August 1792, during the attack on the Tuileries Palace, he met with other key figures like Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins, as members of the Insurrectionary Commune, in the critical hours leading up to the overthrow of the monarchy. Later that day, he was elected as one of the deputy-commissioners of the sections, who soon formed the general council of the Paris Commune. He was subsequently accused of complicity in the September Massacres at the Prison de l'Abbaye.

2.2. Role in the National Convention

Like Robespierre, Danton, and Collot d'Herbois, Billaud-Varenne was elected as a deputy of Paris to the National Convention. Upon entering the Convention, he immediately spoke in favor of the complete abolition of the Bourbon monarchy. The very next day, he demanded that all official acts be dated from the "Year I of the French Republic", a measure that was adopted a little over a year later with the establishment of the French Revolutionary Calendar.

During the trial of Louis XVI, Billaud-Varenne added new charges to the existing accusations against the King. He controversially proposed denying the King legal counsel and ultimately voted for his death "within 24 hours." On 2 June 1793, amidst Jean-Paul Marat's anti-Girondist instigations, Billaud-Varenne proposed a decree of accusation specifically targeting the Girondin faction. A week later, at the Jacobin Club, he outlined an ambitious program that the Convention would soon implement. This program included the expulsion of all foreigners deemed hostile to the Revolution, the establishment of a tax on the wealthy to fund revolutionary efforts, the deprivation of citizenship rights for all "anti-social" individuals, the creation of a dedicated French Revolutionary Army, the close monitoring of all officers and former nobles (those from aristocratic families who had lost their status after the abolition of feudalism), and the imposition of the death penalty for generals who failed in the French Revolutionary Wars. These proposals underscored his commitment to radical measures for securing the Revolution's gains.

2.3. The Reign of Terror and Committee of Public Safety

Billaud-Varenne held a critical position within the Committee of Public Safety and was a fervent advocate for the Reign of Terror, which he viewed as an indispensable instrument for the Revolution's survival and its social transformation.

2.3.1. Advocacy for the Terror

On 15 July, Billaud-Varenne delivered a forceful speech in the Convention, directly accusing the Girondins. In August, he was dispatched as a representative on mission to the départements of Nord and Pas-de-Calais, where he demonstrated an unyielding approach towards all suspected enemies of the Revolution.

Upon his return, the widespread calamities of the summer of 1793 prompted the Paris Commune to organize an insurrection. This uprising ultimately propelled Billaud-Varenne to a position within the most powerful body in France. When the popular uprising occurred on 5 September, with the Commune marching on the National Convention, Billaud-Varenne was one of the principal speakers agitating for a change in leadership. He demanded a new war plan from the Ministry of War and called for the creation of a new committee to oversee the entire government, effectively superseding the existing Committee of Public Safety. To appease the insurrectionists, Billaud-Varenne was appointed President of the National Convention for a special two-week session that very night. The following day, he was officially named to the Committee of Public Safety, along with Collot d'Herbois. Their inclusion was seen as a strategic move to co-opt the radical elements of the Paris Commune.

Once on the Committee of Public Safety, Billaud-Varenne became a vocal defender of its authority, advocating for unity rather than further changes to its structure. Based in Paris for much of this period, Billaud-Varenne, in collaboration with Bertrand Barère, focused on developing the administrative apparatus and consolidating the Committee's power. To achieve this, in early December, he proposed a radical centralization of authority, which became known as the Law of 14 Frimaire. This law placed surveillance, economic requisition, the dissemination of legislative news, the control of local administrators, and the activities of representatives on mission directly under the Committee's purview. He was also instrumental in defending the Terror itself. When a measure was passed in mid-November 1793 granting the accused the right of defense, Billaud-Varenne delivered his famous words in defense of the Terror: "No, we will not step backward, our zeal will only be smothered in the tomb; either the revolution will triumph or we will all die." The law allowing the right of defense was swiftly overturned the next day. Billaud-Varenne was deeply involved in the Reign of Terror's Committee of Public Safety, which decreed the mass arrest of all suspects, established a revolutionary army, officially named the extraordinary criminal tribunal the "Revolutionary Tribunal" (on 29 October 1793), demanded the execution of Marie Antoinette, and subsequently targeted figures like Jacques René Hébert and Danton. During this period, he also published Les Éléments du républicanisme, in which he advocated for a division of property among citizens, reflecting his commitment to social equity.

2.3.2. Relationship with Robespierre

As 1794 progressed, the political relationship between Billaud-Varenne and Maximilien Robespierre began to deteriorate, transitioning from an initial alliance to growing ideological conflict. Robespierre became increasingly critical of what he termed "overzealous" factions, believing that both extreme pro-Terror and overly indulgent positions posed dangers to the Revolution's stability. He viewed figures like Billaud-Varenne, Collot d'Herbois, and Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier as problematic due to their aggressive attacks on Church property or their excessive vigor in pursuing revolutionary justice, such as Collot's actions in Lyon. The dechristianization program, in particular, was seen as divisive and unnecessary by some within the Convention.

Furthermore, the Law of 22 Prairial, passed on 10 June 1794, severely curtailed the power of the Committee of General Security, the Convention's police wing, which was strongly anti-clerical. This law, which drastically reduced the right of defense to merely an appearance before court while significantly expanding the list of capital crimes, directly led to the "Great Terror," a period of seven weeks during which the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris executed more individuals than in the preceding fourteen months. Although Billaud-Varenne publicly defended this law in the Convention, it became a primary catalyst for the eventual backlash against the Committee.

Serious disagreements began to fracture the Committee of Public Safety, with Billaud-Varenne and Collot d'Herbois increasingly pitted against Robespierre and his protégé, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just. On 26 June, they clashed over the appointment of a new prosecutor to the Revolutionary Tribunal. Another argument erupted on 29 June, which, though its precise cause (possibly the Catherine Théot affair or the Law of 22 Prairial) is debated, culminated in Billaud-Varenne denouncing Robespierre as a dictator. Robespierre, infuriated, stormed out of the Committee headquarters and ceased attending meetings. With tensions mounting and the daily rate of executions in Paris escalating from five per day in Germinal to twenty-six per day in Messidor, Billaud-Varenne and Collot d'Herbois grew fearful for their own safety.

2.4. Thermidorian Reaction

Billaud-Varenne played a crucial and active role in the Thermidorian coup, which led to the downfall of Robespierre and his faction. During the early days of Thermidor, Bertrand Barère attempted to mediate a compromise within the splintering Committee. However, Robespierre remained convinced that the Convention required further purging. On 8 Thermidor, he delivered a speech to the Convention that would ignite the Thermidorian Reaction. In his address, he spoke vaguely of "monsters" and a conspiracy threatening the Republic, alarming many within the body. When pressed to name the individuals involved in this alleged conspiracy, Robespierre refused, leading to accusations that he intended to indict members of the Convention en masse without a hearing.

That evening, Robespierre repeated his speech to an enthusiastic audience at the Jacobin Club. Collot d'Herbois and Billaud-Varenne, sensing they might be targets of Robespierre's accusations, attempted to defend themselves but were shouted down and expelled from the club amidst cries for "la guillotine." They then returned to the Committee of Public Safety, where they found Saint-Just preparing a speech he intended to deliver the following day. Believing Saint-Just was drafting their denunciation, Collot and Billaud-Varenne, joined by Barère, engaged in a final heated argument within the Committee, accusing Saint-Just of "dividing the nation." Following this confrontation, they left the Committee and began organizing the final elements of the Thermidorian Reaction.

On 9 Thermidor, Billaud-Varenne was instrumental in the decisive move against Robespierre and his allies. As Saint-Just began his speech in the Convention, he was deliberately interrupted by another conspirator, Jean-Lambert Tallien. Billaud-Varenne then took the floor, with Collot d'Herbois presiding over the debates. In a carefully planned and eloquent denunciation, Billaud-Varenne directly accused Robespierre of conspiring against the Republic. This speech, along with others, was well-received by the Convention. After continued debate, arrest warrants were issued for Robespierre, Saint-Just, and their allies. Following a brief armed standoff, the conspirators prevailed, and Robespierre and his supporters were executed the next day.

3. Post-Revolution and Exile

Following the Thermidorian Reaction, Billaud-Varenne experienced a significant decline in political influence, leading to his arrest, deportation, and an enduring life in exile that underscored the severe consequences of his revolutionary actions.

3.1. Arrest and Deportation

Despite his role in Robespierre's downfall, Billaud-Varenne was soon to find himself a target. Having been too closely associated with the excesses of the Reign of Terror, he was swiftly attacked within the Convention for his perceived ruthlessness. He was part of the Crêtois, the last group of deputies from The Mountain. A commission was appointed to investigate his conduct and that of other former members of the Committee of Public Safety. Billaud-Varenne was arrested on 2 March 1795. As a direct consequence of the Jacobin-led insurrection of 12 Germinal of the Year III (1 April 1795), the Convention decreed his immediate deportation to French Guiana. He was exiled alongside Collot d'Herbois and Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac. He also presided over the persecution of Louis Marie Turreau and Jean-Baptiste Carrier for their massacres during the War in the Vendée, which ended with their execution.

3.2. Life in Exile and Final Years

In French Guiana, Billaud-Varenne adapted to his new circumstances, engaging in farming. He also formed a relationship with a black slave girl named Brigitte, who became his concubine and later his wife. Following Napoleon Bonaparte's 18 Brumaire coup, the French Consulate offered Billaud-Varenne a pardon in 1814, but he steadfastly refused it, unwilling to legitimize the new government he considered a betrayal of revolutionary ideals. He did not return to France.

In 1816, he left Guiana and traveled to New York City, where he resided for a few months. He then relocated to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, where he served as an advisor and counsellor to the high court. Alexandre Pétion, the President of Haiti, granted him a pension, which he continued to receive until his death. Reflecting on the French attempts to recolonize Haiti and Louis XVIII's diplomatic efforts to regain control of the island, Billaud-Varenne famously declared to Pétion: "The biggest fault you committed, in the course of the revolution of this country, is not having sacrificed all the settlers, down to the last one. In France we made the same mistake, by not causing the last of the Bourbons to perish."

Billaud-Varenne died in Port-au-Prince on 3 June 1819. Among his last recorded words, he stated: "My bones, at least, will rest on a land that wants Liberty; but I hear the voice of posterity accusing me of having spared the blood of the tyrants of Europe too much." In his will, he bequeathed all his possessions to his wife, Brigitte, writing: "I give this surplus, whatever its value may be, to this honest girl; as much to repay her for the immense services she has rendered me for over eighteen years as to acknowledge the new and most complete proof of her unwavering attachment, by consenting to follow me wherever I go."

4. Political Thought and Ideology

Billaud-Varenne's political thought was rooted in a fervent commitment to radical republicanism and a belief in the necessity of profound social transformation. He advocated for a society founded on principles of equality and social equity, demanding a division of property among citizens as articulated in his work Les Éléments du républicanism. He viewed the French Revolution as a struggle to dismantle the vestiges of the old order and establish a truly republican system.

His justification for the Reign of Terror stemmed from a conviction that such extreme measures were vital to consolidate revolutionary gains and purge society of its enemies, whom he saw as threats to the very existence of the Republic. For Billaud-Varenne, the use of terror was not merely punitive but a necessary tool for survival, to enforce social change and prevent counter-revolution. This perspective is encapsulated in his statement defending the Terror: "No, we will not step backward, our zeal will only be smothered in the tomb; either the revolution will triumph or we will all die."

Despite his radicalism, his later conflicts with Robespierre, particularly over the centralization of power, suggest a potential concern for the dangers of individual dictatorship, even if his own methods were seen as dictatorial. His unwavering stance against pardons from Napoleon and his final declaration in Haiti, where he lamented not having been more ruthless with "tyrants," underscore his consistent and uncompromising dedication to the ideals of liberty and the complete eradication of monarchical power, reflecting an enduring commitment to the revolutionary principles he espoused throughout his life.

5. Works

Billaud-Varenne's published writings offer significant insight into his intellectual contributions, political theories, and personal reflections on the French Revolution. His notable works include:

- Despotisme des ministres de France, combattu par les droits de la Nation, par les loix fondamentales, par les ordonnances... (Despotism of the ministers of France, combatted by the rights of the Nation, by the fundamental laws, by the ordinances...), published in Paris in 1789. This three-volume work, initially published in Amsterdam, was an early articulation of his anti-authoritarian views.

- Mémoires écrits au Port-au-Prince en 1818, contenant la relation de ses voyages et aventures dans le Mexique, depuis 1815 jusqu'en 1817 ("Memoirs written in Port-au-Prince in 1818, containing the relation of his voyages and adventures in Mexico, from 1815 to 1817"), published posthumously in Paris in 1821. These memoirs are generally considered to be forgeries.

- Billaud Varenne membre du comité de salut public : Mémoires inédits et Correspondance. Accompagnés de notices biographiques sur Billaud Varenne et Collot d'HerboisFrench ("Billaud Varenne, member of the Committee of Public Safety: Unpublished memoirs and correspondence. Accompanied by biographical notes on Billaud Varenne and Collot d'Herbois"), published in Paris by Librairie de la Nouvelle Revue in 1893, edited by Alfred Begis.

6. Historical Assessment

Billaud-Varenne occupies a complex and often controversial place in the history of the French Revolution. His historical assessment reflects both his significant impact and the criticisms leveled against his uncompromising approach.

6.1. Evaluation

Billaud-Varenne was a central figure during the first part of the French Revolution, particularly during its most radical phase. As a key architect of the Reign of Terror, his actions had profound consequences for the trajectory of the Revolution and the lives of countless individuals. He played a vital role in centralizing the power of the Committee of Public Safety through legislation like the Law of 14 Frimaire, aiming to consolidate revolutionary authority. Despite his critical involvement in such a pivotal period, he remains a figure who is relatively little studied or understood by historians, leading to varied interpretations of his true influence and motivations. His actions in orchestrating the downfall of Robespierre, whom he accused of dictatorship, highlight his capacity for shifting allegiances and his commitment to what he perceived as the purity of revolutionary ideals, even if those ideals justified extreme violence.

6.2. Criticism and Controversy

Billaud-Varenne has faced significant criticism, particularly concerning his perceived ruthlessness and uncompromising political stance during the Reign of Terror. He was attacked for his severity, especially after the Thermidorian Reaction, when his conduct as a member of the Committee of Public Safety was formally investigated. His advocacy for the Terror, including his role in overturning the right of defense for the accused, demonstrates a disregard for due process and individual liberties. While he opposed what he saw as Robespierre's emerging dictatorship, his own methods and policies contributed to the dictatorial nature of the revolutionary government. He was frequently denounced as an "extreme terrorist" by his opponents, a label that accurately reflects his willingness to employ violent means to achieve revolutionary ends. His final words in exile, expressing regret for "having spared the blood of the tyrants of Europe too much," further illustrate his unyielding and extreme ideology, which prioritized revolutionary purity over human cost, thus having a deeply negative impact on human rights during the Revolution.