1. Life

Hugh's life was marked by a strong monastic calling from a young age, leading him to become the revered Abbot of Cluny and a pivotal figure in 11th-century ecclesiastical and political landscapes.

1.1. Early Life and Monastic Vocation

Hugh was born on 13 May 1024. He was descended from one of the noblest families in Burgundy, being the eldest son of Dalmas I of Semur, Seigneur of Semur, and Aremberge of Vergy, who was the daughter of Henry I, Duke of Burgundy. While his father had wished for him to become a knight, Hugh displayed a clear aversion to this path. Recognizing his inclination towards scholarly pursuits, his father entrusted him to his grand-uncle, Hugh, Bishop of Auxerre, for preparation for the priesthood. Under his relative's protection, Hugh received his early education at the monastery school attached to the Priory of St. Marcellus near Chalon.

At the age of fourteen, Hugh entered the novitiate at Cluny Abbey. Demonstrating profound commitment, he took his monastic vows at the age of fifteen. He later rose to the position of prior within the abbey.

1.2. Appointment as Abbot and Early Activities

In 1048, as Prior, Hugh accompanied the Bishop of Toul, Bruno von Egisheim-Dagsburg, who was the pope-elect, to Rome. There, he witnessed Bruno's consecration as Pope Leo IX. The following year, in 1049, Prior Hugh was elected as the Abbot of Cluny, succeeding Odilo of Cluny. He would hold this esteemed position for over 60 years.

During his early years as abbot, Hugh actively participated in important ecclesiastical gatherings. He attended the Council of Reims in 1049 and the Council of Tours in 1054. He also participated in local councils in Rome in 1050, 1059, and 1063. In 1072, he was present at the Reichstag in Worms. In March 1058, Hugh was in Florence, where he attended Pope Stephen IX on his deathbed.

2. Major Achievements and Contributions

Abbot Hugh's leadership marked a period of immense growth and influence for Cluny Abbey, leading to its greatest architectural triumph and the widespread expansion of its monastic order.

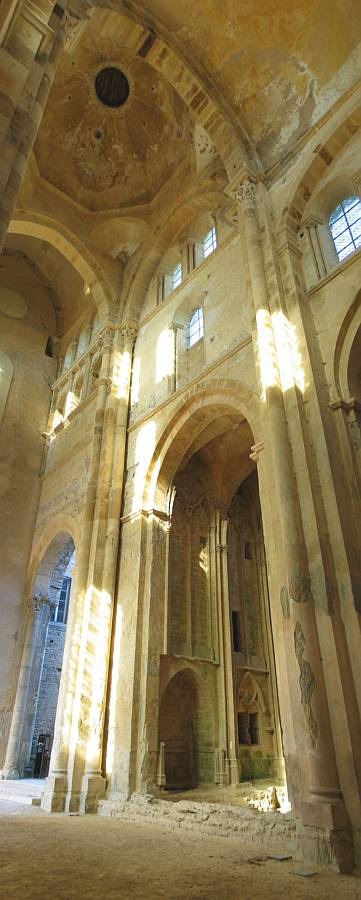

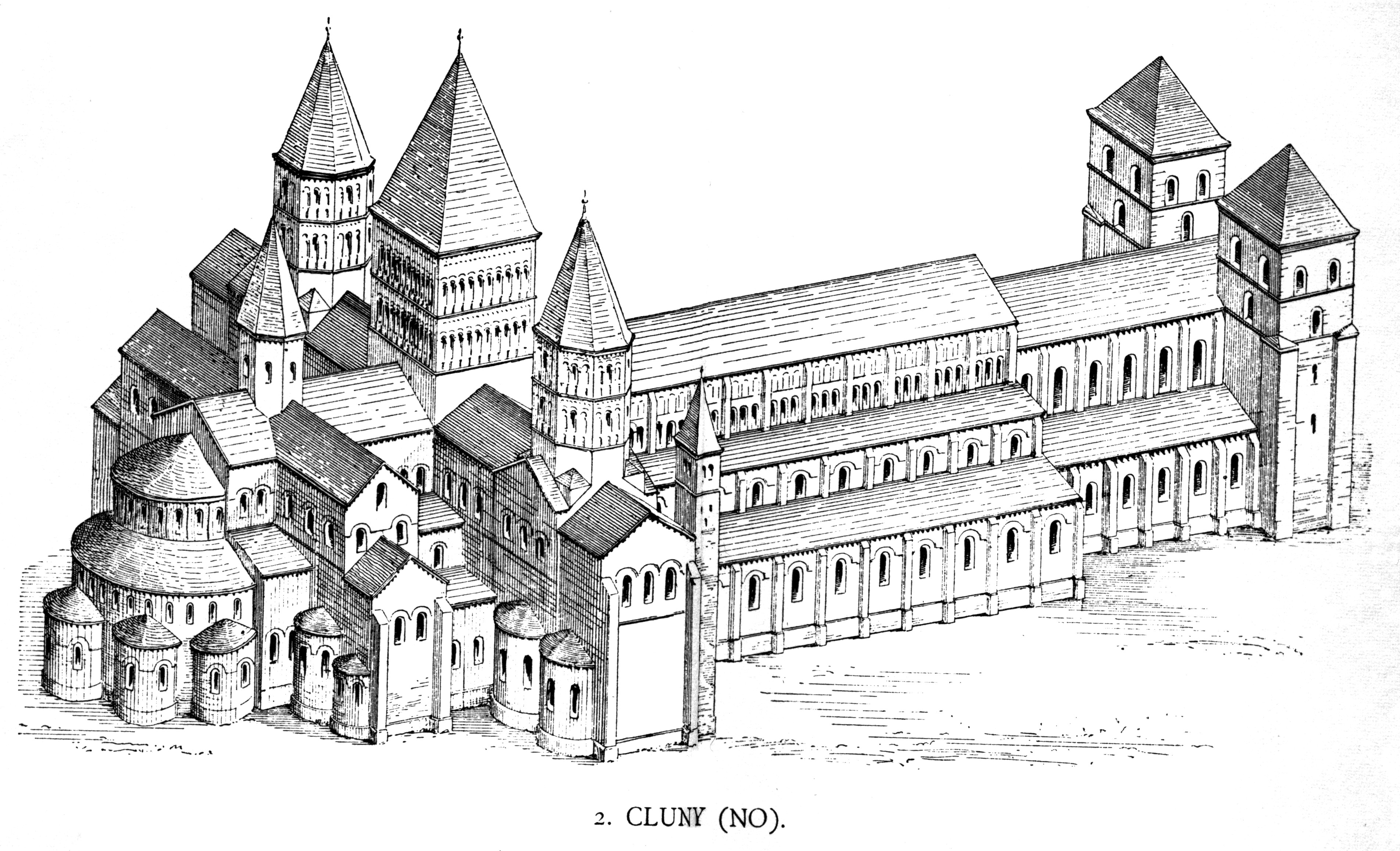

2.1. Construction of Cluny III Abbey Church

Under Hugh's abbacy, Cluny Abbey reached the zenith of its glory. Hugh was personally responsible for initiating and overseeing the construction of the third and most impressive abbey church at Cluny, often referred to as Cluny III.

The financing for this monumental undertaking was largely secured through a substantial annual census established by Ferdinand I of León, who served as regent of the Castile and León between 1053 and 1065. This initial annual payment amounted to 1,000 aurei, a gold coin of the era. This amount was later reconfirmed by Alfonso VI of León and Castile in 1077 and then doubled by him in 1090. This financial support represented the largest annual pension Cluny Abbey ever received from any monarch or commoner.

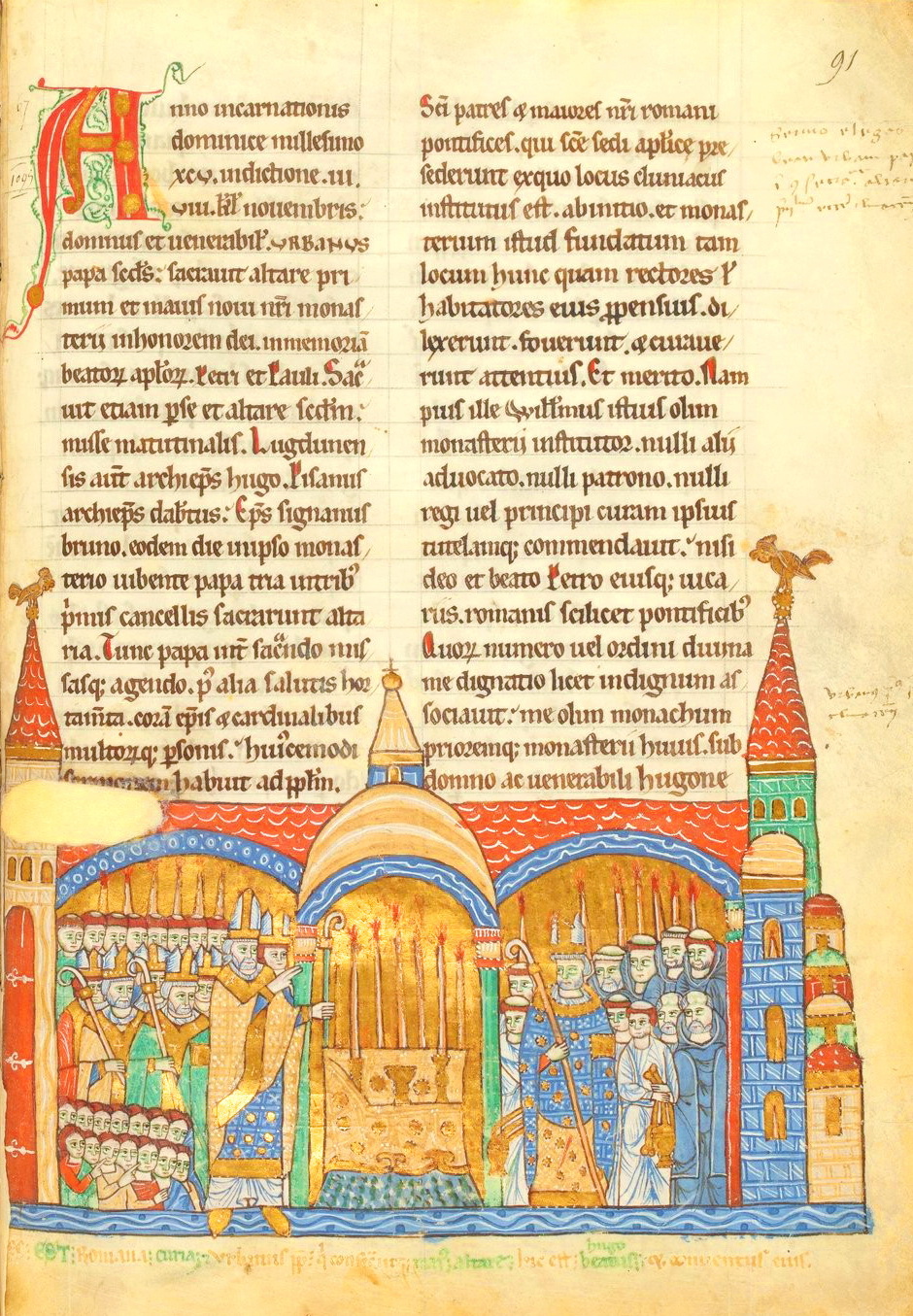

With these funds, Hugh began construction of the impressive abbey church in 1088. The completed structure measured 614 ft (187 m) in length, making it an architectural marvel of its time. It featured a narthex, five naves, an elongated choir with waiting rooms and radiating chapels, a double transept, and five towers. For many centuries, Cluny III stood as the largest religious building in Europe, a distinction it held until the reconstruction of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City in the 16th century. In October 1085, Pope Urban II, who had previously served as a prior at Cluny under Hugh, consecrated the high altar of the new church.

2.2. Expansion of the Cluniac Order

Hugh was instrumental in expanding the influence of the Cluniac reform movement across Europe. In 1079, Philip I of France transferred the Saint-Martin-des-Champs monastery in Paris to the control of Cluny Abbey, further extending its reach within France.

The Cluniac order also spread significantly north of the Loire River through the transfer of the Flemish monastery of St. Bertin to Hugh's control. This occurred after Clementia of Burgundy married, and she facilitated this significant transfer. This act initiated a broad monastic reform movement throughout Flanders. In 1089, Hugh established the Priory of St Pancras in England, marking the first Cluniac monastic house in that country and establishing a foothold for the order's expansion.

3. Political Influence and Diplomatic Activities

Beyond his monastic responsibilities, Hugh of Cluny wielded considerable influence in the political and diplomatic arenas of the medieval period, engaging with powerful rulers and popes.

3.1. Relationships with Royalty and Papacy

Hugh's connections extended to the highest echelons of secular and ecclesiastical power. His close relationship with Pope Urban II, who had served as a prior under Hugh at Cluny, significantly enhanced Hugh's own power and made him one of the most influential figures of the late 11th century. Urban II's consecration of the high altar of Cluny III further exemplified this bond.

Hugh also maintained important relationships with the royalty of the Iberian Peninsula. His influence over Ferdinand I of León and Alfonso VI of León and Castile was notable, including his role in securing Alfonso's release from his brother Sancho's prison. Alfonso VI's generous financial contributions to the construction of Cluny III underscored the political weight Hugh carried.

Perhaps one of his most prominent political roles involved his relationship with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, to whom Hugh was a godfather. Hugh attempted to mediate the intense conflict between Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV during the Investiture Controversy, particularly during the dramatic events at Canossa. Although his efforts to reconcile the two powerful figures were ultimately unsuccessful in the long term, his involvement highlights his significant standing and the trust placed in him by both sides. This episode remains a famous historical anecdote.

3.2. Diplomatic Contributions

Hugh was not merely an influential advisor but also an active diplomat. He undertook missions on behalf of the Church to various regions, including Germany and Hungary, demonstrating his extensive involvement in the Church's international relations and efforts to resolve disputes and foster alliances.

4. Death

Abbot Hugh of Cluny passed away on the evening of Easter Monday, 28 April 1109. He died in the Lady Chapel at Cluny, at the age of 85.

5. Legacy and Veneration

Hugh's profound impact on the Church and monastic life continued long after his death, cemented by his canonization and the enduring veneration of his memory, despite the tragic fate of his physical remains.

5.1. Canonization and Reverence

Hugh of Cluny was canonized as a saint by the Catholic Church. On 6 January 1120, during a visit to Cluny, Pope Callixtus II officially declared Hugh a saint at the request of the monks. His feast day is celebrated on 29 April. He is revered as a patron against fever.

The Roman Martyrology, the official catalogue of saints and martyrs recognized by the Catholic Church, describes him as follows: "In Cluny, Burgundy, France, Saint Hugh, abbot, who for sixty-one years healthily governed this monastery, always devoted to alms and prayer, a guardian of monastic discipline, an energetic promoter, a zealous administrator of the holy Church, and a missionary." The monk Gilles de Paris, who later became a cardinal of Frascati, penned a biography of Hugh titled Vie de Saint-Hugues (Life of Saint Hugh).

5.2. Historical Impact and Evaluation

Hugh's more than six decades as Abbot of Cluny represented a period of unprecedented growth and spiritual influence for the Cluniac Order. He was a dedicated guardian and energetic promoter of monastic discipline, ensuring the spiritual vitality and organizational strength of the monasteries under his care. His zealous management of the holy Church and his role as a missionary further underscore his comprehensive impact on medieval society and religious institutions. He expanded the Cluniac network across Europe, making it one of the most powerful and respected monastic forces of the era, profoundly shaping the religious and cultural landscape of the Middle Ages.

5.3. Fate of Relics

Tragically, many of Saint Hugh's relics were pillaged and destroyed during the turbulent period of the French Wars of Religion. In 1562, or perhaps as late as 1575 according to some accounts, Huguenots plundered Cluny Abbey, and the bodies of saints, including Hugh, were burned, with their ashes scattered to the wind.