1. Overview

Hans Kelsen was an Austrian and later American jurist, legal philosopher, and political philosopher, widely considered one of the preeminent jurists of the 20th century. He is best known for his groundbreaking "Pure Theory of Law" (Reine RechtslehrePure Theory of LawGerman), a systematic effort to describe law as a hierarchy of binding norms, independent of moral or political evaluations. This theory sought to establish legal science as an objective discipline, distinct from other social sciences and free from ideological influence. Kelsen also made significant contributions to constitutional law, notably as the principal architect of the 1920 Austrian Constitution, which introduced the modern European model of constitutional review, setting up specialized courts to resolve constitutional disputes.

Throughout his career, Kelsen was a fervent advocate for democracy, championing its commitment to value relativism, compromise, and the protection of minority rights. He sharply contrasted democratic principles with the absolutist and authoritarian tendencies he identified in totalitarianism, particularly in his critiques of Marxism and Bolshevism. His experiences, including forced migrations due to the rise of Nazism, deepened his commitment to the rule of law and international legal order. His extensive work on international law and international organizations, such as the United Nations, further solidified his legacy as a scholar who sought to establish legal foundations for a peaceful and just world order, including his influential contributions to the legal basis for war crimes trials after World War II.

2. Biography

Hans Kelsen's life spanned a tumultuous period of European and global history, marked by two World Wars, the rise of totalitarian regimes, and the reshaping of international order. His personal and professional journey was deeply intertwined with these events, from his academic rise in Vienna to his forced exile and eventual establishment in the United States.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Hans Kelsen was born in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, on October 11, 1881, into a middle-class, German-speaking Jewish family. His father, Adolf Kelsen, hailed from Galicia, while his mother, Auguste Löwy, was from Bohemia. Hans was their first child, followed by two younger brothers and a sister. In 1884, when Hans was three years old, his family relocated to Vienna.

Kelsen received his secondary education at the Akademisches Gymnasium in Vienna. Following his graduation, he pursued legal studies at the University of Vienna, a period during which he demonstrated exceptional academic prowess. He earned his doctorate in law (Dr. jurisDoctor of LawLatin) on May 18, 1906, and subsequently obtained his habilitation-a qualification allowing him to lecture at a university-on March 9, 1911.

During his early life, Kelsen underwent two religious conversions. On June 10, 1905, while writing his dissertation on Dante Alighieri and Catholicism, he was baptized as a Roman Catholic. Several days before his marriage to Margarete Bondi (1890-1973) on May 25, 1912, both he and Margarete converted to Lutheranism of the Augsburg Confession. They had two daughters.

2.2. Years in Austria (1911-1930)

Kelsen's academic career in Austria flourished following his habilitation in 1911, with his thesis forming the basis of his first major work on legal theory, Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre entwickelt aus der Lehre vom Rechtssatze ("Main Problems in Theory of Public Law, Developed from Theory of the Legal Statement"). His 1905 book, Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri (The Theory of the State of Dante Alighieri), was his first contribution to political theory, rigorously examining the "two swords doctrine" of Pope Gelasius I and Dante's stance in the debates between the Guelphs and Ghibellines. This early work also highlighted the historical importance of Niccolò Machiavelli and Jean Bodin in the evolution of modern legal theory, with Kelsen seeing Machiavelli as a counter-example of exaggerated executive power without legal restraints, which influenced his emphasis on judicial review.

A significant period for Kelsen was his study at the University of Heidelberg in 1908, where he was mentored by the distinguished jurist Georg Jellinek. Kelsen began to solidify his position on the identity of law and state, building upon Jellinek's initial steps. While Jellinek proposed a "self-limitation of the state" theory to reconcile state independence with legal order, Kelsen ultimately rejected this as still dualistic. He argued that the dualism of state and law was a "pseudo-problem" resulting from the personification of abstract systems. This critique was shared by French jurist Léon Duguit, leading Kelsen to firmly endorse the doctrine of the identity of law and state, viewing the state as a legal entity and the legal order itself.

In 1919, Kelsen was appointed full professor of public law and administrative law at the University of Vienna, where he also established and edited the Zeitschrift für öffentliches Recht (Journal of Public Law). During this period, he became a central figure in what became known as the "Vienna School" of legal thought, attracting prominent students and colleagues such as Alfred Verdross, Eric Voegelin, Alf Ross, Adolf Julius MerklGerman, Felix Kaufmann, Fritz Sander, Charles Eisenmann, and Luis Legaz y Lacambra. He also interacted with figures from Austrian Marxism like Otto Bauer and Max Adler, as well as economists like Joseph Schumpeter and Ludwig von Mises.

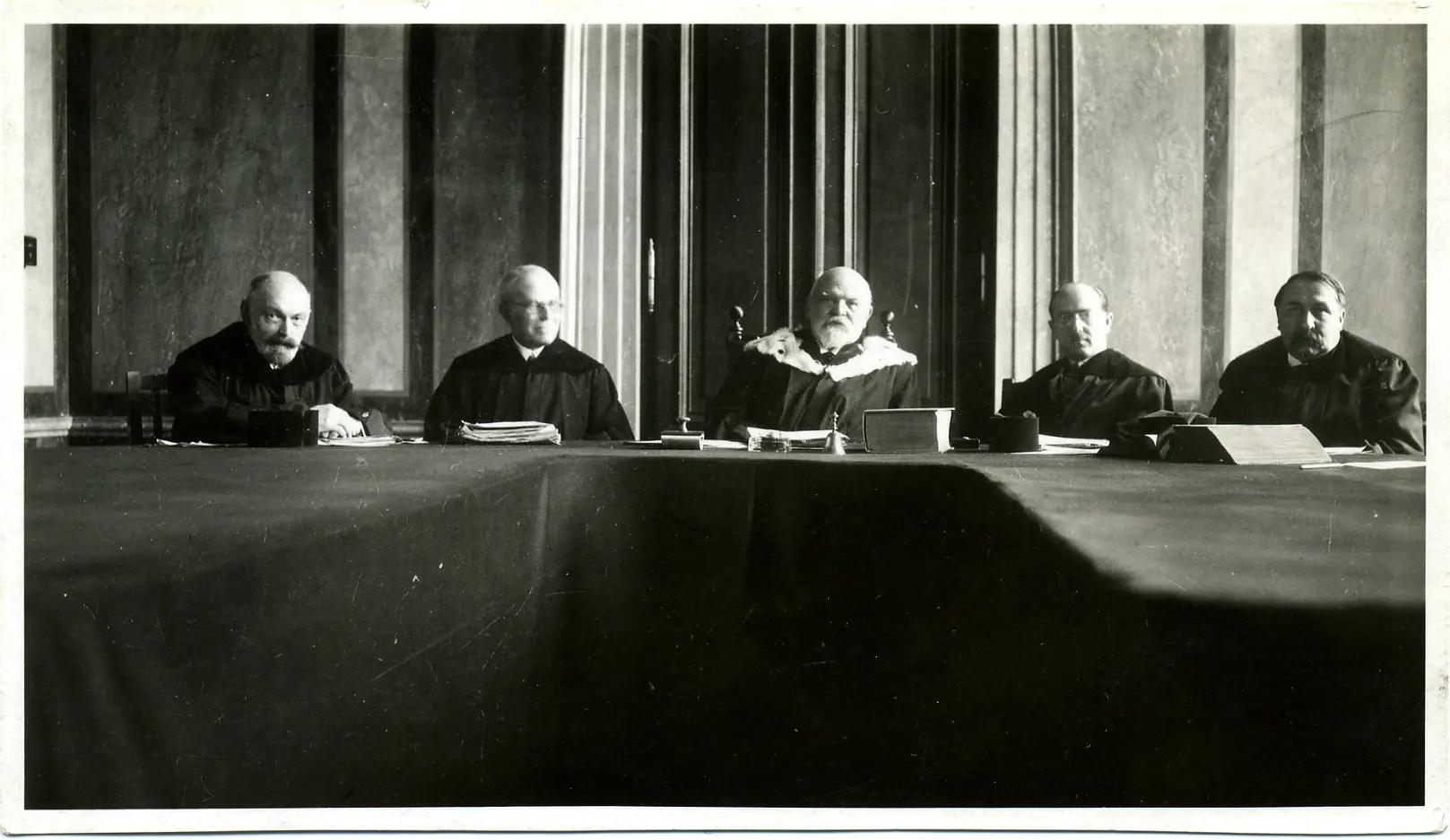

At the behest of Chancellor Karl Renner, Kelsen played a pivotal role in drafting the new Austrian Constitution, which was enacted in 1920. This document, with amendments, continues to form the basis of Austrian constitutional law today. Kelsen was subsequently appointed to the Constitutional Court of Austria for a lifetime tenure. His work during these years, emphasizing a Continental form of legal positivism and law-state monism, was a significant development from earlier dualistic approaches found in scholars like Paul Laband and Carl Friedrich von Gerber.

Between 1920 and 1925, Kelsen published several influential works, including Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (The Problem of Sovereignty and Theory of International Law), Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (On the Essence and Value of Democracy), Der soziologische und der juristische Staatsbegriff (The Sociological and Juristic Concepts of the State), Österreichisches Staatsrecht (Austrian Public Law), and Allgemeine Staatslehre (General Theory of the State). He also published Das Problem des Parlamentarismus (The Problem of Parliamentarianism) and, in the late 1920s, Die philosophischen Grundlagen der Naturrechtslehre und des Rechtspositivismus (The Philosophical Foundations of the Doctrine of Natural Law and Legal Positivism).

Kelsen's prominent role as the inventor of the modern European model of constitutional review saw its first introduction in Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1920. This model established a separate constitutional court with sole responsibility for constitutional disputes, differing from the common-law system where general jurisdiction courts handle such reviews. Kelsen was the primary author of the statutes for this court in the Austrian state constitution. However, political controversies, particularly regarding the court's liberal interpretation of divorce provisions, led to increasing pressure on Kelsen from the predominantly Catholic and conservative administration. Although sympathetic to the Social Democratic Party of Austria, Kelsen was not a member. Amidst this escalating conservative climate, he was removed from the court in 1930.

2.3. European Exile (1930-1940)

Following his removal from the Constitutional Court, Kelsen accepted a professorship at the University of Cologne in 1930. However, with the rise of National Socialism in Germany, he was dismissed from his post in 1933 due to his Jewish heritage. This forced Kelsen to relocate to Geneva, Switzerland, where he taught international law at the Graduate Institute of International Studies from 1934 to 1940.

During his time in Geneva, Kelsen published the first edition of his magnum opus, Reine Rechtslehre (Pure Theory of Law), in 1934, at the age of 52. His interest in international law deepened significantly during this period, particularly in response to what he perceived as the excessive idealism and lack of sanctions in the 1929 Kellogg-Briand Pact. Kelsen became a strong proponent of the sanction-delict theory of law, arguing for the necessity of consequences for illicit actions by states.

It was in Geneva that Kelsen became an advisor for the habilitation dissertation of Hans Morgenthau, who had also fled Germany. Kelsen and Morgenthau shared a strong opposition to Carl Schmitt's views, which prioritized the political concerns of the state over adherence to the rule of law. Their shared commitment to the rule of law and rejection of the National Socialist school of political interpretation forged a lifelong collegial relationship. Kelsen's vigorous defense helped Morgenthau secure his habilitation, which was initially met with resistance from the Geneva faculty.

From 1936 to 1938, Kelsen briefly held a professorship at the German University in Prague before returning to Geneva, where he remained until 1940. His focus on international law continued to intensify, particularly on the topic of international war crimes, a subject he would pursue extensively after his departure for the United States.

2.4. American Years (1940-1973)

In 1940, at the age of 58, Hans Kelsen and his family were forced to flee Europe on the last voyage of the SS Washington, departing from Lisbon on June 1. He settled in the United States, delivering the prestigious Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures at Harvard Law School in 1942. Although supported by Roscoe Pound for a faculty position at Harvard, Kelsen faced opposition from scholars like Lon Fuller, who disagreed with Kelsen's separation of the philosophical definition of justice from the application of positive law. Fuller argued that Kelsen's exclusion of justice as an "irrational ideal" fundamentally shaped his theory and limited its understanding.

In 1945, Kelsen became a full professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, where he remained until his official retirement in 1952. During these years, Kelsen increasingly dedicated his work to issues of international law and international institutions, particularly the United Nations. From 1953 to 1954, he served as the Charles H. Stockton Professor of International Law at the United States Naval War College.

A significant practical legacy of Kelsen's work was his influence on the prosecution of political and military leaders at the end of World War II at the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals. His extensive research on international war crimes, spanning from the 1930s into the early 1940s, culminated in the conviction of over a thousand war criminals. Kelsen's essays, such as "Collective and Individual Responsibility in International Law with Particular Regard to Punishment of War Criminals" (1943), "The Rule Against Ex Post Facto and the Prosecution of the Axis War Criminals" (1944), and "Will the Judgment In the Nuremberg Trial Constitute a Precedent In International Law?" (1947), provided crucial legal arguments for these trials. In his 1948 essay, "Collective and Individual Responsibility for Acts of State in International Law," Kelsen further articulated his views on the distinction between respondeat superior and the acts of state doctrine in the context of war crimes prosecution.

Shortly after the drafting of the UN Charter began in San Francisco on April 25, 1945, Kelsen commenced writing his comprehensive 700-page treatise, The Law of the United Nations (New York, 1950), which, along with a 200-page supplement in 1951, became a standard textbook on the UN for over a decade. In 1952, he also published Principles of International Law, reprinting it in 1966.

Kelsen also engaged in the ideological debates of the Cold War. In 1955, he published a 100-page essay, "Foundations of Democracy," in the journal Ethics, expressing a passionate commitment to the Western model of democracy over Soviet and National Socialist forms of government. This essay also critiqued the 1954 book on politics by his former student, Eric Voegelin. In his 1956 book, A New Science of Politics, Kelsen provided a point-by-point criticism of the excessive idealism and ideology he perceived in Voegelin's work. This was followed by a collection of essays on justice, law, and politics, What is Justice?, published in 1957.

A posthumously published work, Secular Religion (2012), written in the 1950s and expanded in the early 1960s, serves as a vigorous defense of modern science against those who, including Voegelin, sought to overturn the accomplishments of the Enlightenment by demanding that science be guided by religion. Kelsen aimed to expose contradictions in the claim that modern science constitutes a "new religion."

After his official retirement in 1952, Kelsen substantially rewrote his 1934 book, Reine Rechtslehre, resulting in a much enlarged "second edition" published in 1960. This revised edition was translated into English in 1967 as Pure Theory of Law.

2.5. Personal Life

Hans Kelsen was married to Margarete Bondi (1890-1973). They had two daughters. His wife's nephew by marriage was the renowned management consultant and author Peter Drucker.

2.6. Death

Hans Kelsen passed away on April 19, 1973, in Orinda, California, at the age of 91.

3. Legal Philosophy

Hans Kelsen's legal philosophy fundamentally reshaped modern legal thought, particularly through his development of a rigorous legal positivism and a structural understanding of legal systems. His objective was to create a pure science of law, distinct from politics, morality, and sociology.

3.1. Pure Theory of Law

Kelsen's most renowned contribution is the "Pure Theory of Law" (Reine RechtslehrePure Theory of LawGerman). This theory aims to describe law as a hierarchy of binding norms, intentionally refraining from evaluating these norms based on moral, ethical, or political considerations. For Kelsen, legal science should be strictly separated from legal politics. The central tenet of the Pure Theory is the notion of the Grundnorm (basic norm). This is a hypothetical, presupposed norm from which all lower norms in a legal system-from constitutional law downwards-derive their validity and binding authority. Legal validity, in Kelsen's view, means that a norm is valid if and only if the organ creating it has been empowered by a higher norm. This concept extends to public international law, which Kelsen also understood as hierarchical. Through this framework, Kelsen argued that the validity of legal norms could be understood without recourse to suprahuman sources such as God, personified Nature, or a personified State or Nation. The Pure Theory is thus a rigorous form of legal positivism, explicitly excluding any idea of natural law.

Kelsen's main exposition of this theory, his book Reine Rechtslehre, was published in two distinct editions. The first appeared in 1934 while he was in exile in Geneva, titled Einleitung in die rechtswissenschaftliche Problematik (Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory). The second, significantly expanded edition was published in 1960, after his formal retirement from the University of California, Berkeley. This second edition was translated into English in 1967 as Pure Theory of Law.

3.2. Judicial Review

Hans Kelsen is widely recognized as the architect of the modern European model of constitutional review, a system distinct from the common-law approach prevalent in countries like the United States. Kelsen advocated for the establishment of a specialized, separate constitutional court with the sole responsibility for adjudicating constitutional disputes within a legal system. This contrasts with the American model, introduced by John Marshall, where courts of general jurisdiction at all levels exercise powers of constitutional review.

Kelsen played a pivotal role in drafting the provisions for judicial review in the constitutions of both Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1920. He carefully delineated and limited the scope of judicial review in these statutes, ensuring its focus remained narrower than the broader powers exercised in the American system. His lifetime appointment to the Constitutional Court of Austria in 1920 allowed him to directly engage with the practical application of his theoretical framework for nearly a decade. His efforts effectively codified Marshall's common law version of judicial review into a legislated form of constitutional law, a model subsequently adopted by many countries in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

3.3. Hierarchical and Dynamic Theory of Law

Central to Kelsen's understanding of legal systems was his concept of hierarchical law, a model he adopted directly from his colleague Adolf Julius MerklGerman at the University of Vienna. This hierarchical description of law served a threefold purpose for Kelsen. First, it was fundamental to his celebrated static theory of law, which comprehensively describes law as a system of norms. This component, spanning nearly a hundred pages in the second edition of his Pure Theory of Law, represented an exhaustive study capable of standing as an independent subject of legal scholarship.

Second, the hierarchy served as a measure of relative centralization or decentralization within a legal order. Third, a fully centralized system of law, in Kelsen's view, would correspond to a unique Grundnorm or basic norm, positioned at the ultimate foundation of the hierarchy and thus not inferior to any other norm.

Complementing the static theory, Kelsen also developed a dynamic theory of law, which he considered of paramount importance. This theory describes the explicit and acutely defined mechanism by which new law is created and existing laws are revised through legislative action, often as a result of political debate in the sociological and cultural domains. Kelsen dedicated one of his longest chapters in the revised edition of Pure Theory of Law to elaborating on the central importance of the dynamic theory of law, emphasizing its role as the driving force behind the continuous evolution and adaptation of the legal system in response to societal needs.

3.4. De-ideologization of Positive Law

Kelsen rigorously insisted on the separation of positive law from ambiguous and ideologically laden concepts, particularly natural law. Having been trained during a period in Europe where natural law was often presented with varied metaphysical, theological, philosophical, political, religious, or ideological components, Kelsen found its definition to be too ambiguous and impractical for a modern scientific understanding of law.

His efforts were directed at establishing legal science as an objective discipline, free from external influences that could distort its descriptive and analytical purity. He explicitly defined positive law to counteract the ambiguities and negative influences he associated with the prevalent uses of natural law. Kelsen dedicated extensive studies to differentiating the methodology of the natural sciences, which rely on causal reasoning, from the methodology of legal sciences, which he argued are more appropriately governed by normative reasoning. This clear delineation of the science of law and legal science was a key methodological distinction for Kelsen, central to his overall project of removing ideological elements from unduly influencing the development of modern 20th-century law. In his later years, Kelsen consolidated these ideas in his unfinished manuscript, posthumously published as Allgemeine Theorie der Normen (General Theory of Norms).

4. Political Philosophy

Hans Kelsen's political philosophy is deeply rooted in his legal theories and was profoundly shaped by his experiences with the rise of totalitarianism in 20th-century Europe. While his legal philosophy focused on the objective description of law, his political thought explored the structure of the state, the values of democracy, and critical analyses of ideologies that threatened individual liberty and the rule of law.

4.1. Concept of State and Sovereignty

Kelsen's theory of the identity of law and state is a cornerstone of his political philosophy. He argued vehemently against dualistic views that conceptualized the state as a separate entity existing prior to or above the legal order. For Kelsen, the state is simply the personification of the legal order itself; there is no state without law, and no law without a state. This functional reading of the state was, for him, the most compatible way to allow for the responsible development of positive law in the face of 20th-century geopolitical demands. He found the traditional concept of a "self-limiting" sovereign state, as proposed by Georg Jellinek, to be a "pseudo-problem" that mistakenly hypostatized an abstraction. Kelsen believed that such dualism impeded the progress of legal science and the effective operation of a legal order.

Consequently, Kelsen took a critical stance on the traditional concept of sovereignty, which often implied an absolute and unlimited power of the state. He viewed the notion of unconditional sovereignty as a dangerous concept that could justify states operating without effective legal restraints. This critique was particularly significant in his work on international law, where he argued that the absolute sovereignty of states presented a major barrier to the binding application of international legal principles. For Kelsen, mitigating traditional notions of sovereignty was essential for the progress and effectiveness of international law in geopolitics, promoting a system where international law could genuinely regulate state conduct and ensure the rule of law across borders.

4.2. Democracy and its Value

Hans Kelsen was a robust and passionate defender of representative democracy, seeing it as the political system most appropriate for a complex society and most aligned with a critical, relativistic worldview. He emphasized that democracy, unlike authoritarian systems, embraces value relativism, acknowledging that ultimate truths about justice or the good life are subjective and not empirically verifiable. This philosophical foundation leads democracy to prioritize compromise and peaceful conflict resolution among diverse viewpoints.

Kelsen highlighted democracy's commitment to protecting minority rights, arguing that a democratic system not only presupposes the existence of minorities but politically acknowledges and protects them, allowing for the free competition of ideas. He contrasted this with authoritarian alternatives, which typically suppress dissent and impose a single, absolute truth. For Kelsen, the essence of democracy lies in the value of freedom, asserting that all individuals should participate equally in the formation of the state's will. He criticized the notion that the majority opinion in a democracy guarantees absolute good or justice, instead emphasizing that its strength lies in allowing political beliefs and opinions to compete equally for public acceptance. He believed that the system of parliamentary democracy, despite its imperfections, represented a peaceful and progressive way to manage societal conflicts, in contrast to violent revolutions.

Kelsen's defense of democracy was deeply rooted in his legal philosophy. He argued that democracy is the only political system that consistently adheres to the rule of law by allowing the dynamic process of law creation and revision through legislative action, shaped by public debate. He famously quoted Joseph Schumpeter's conviction to "realize the relative validity of one's convictions and yet stand for them unflinchingly," aligning it with his own defense of democracy.

4.3. Critique of Marxism and Bolshevism

Kelsen developed a comprehensive critique of Marxist political theory and Bolshevism, particularly detailed in his 1920 work Sozialismus und Staat (Socialism and State) and his revised 1929 edition of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (On the Essence and Value of Democracy). While he sympathized with social democratic ideals, he maintained a neutral stance regarding political parties. His critique focused on what he perceived as the inherent authoritarianism and rejection of democratic principles within these ideologies.

Kelsen argued that the Communist Manifesto's assertion that the proletariat would "win the battle of democracy" to establish its class rule was self-contradictory in a multi-party system. In a democracy with universal suffrage, workers, employers, proletarians, and bourgeoisie all possess equal political rights, precluding class domination. He posited that political power is held by political parties, meaning that a proletarian party, not the class itself, would seize power.

Kelsen criticized the Marxist vision of a future society where exploitation and class conflict vanish. He questioned whether human nature would fundamentally change to enable spontaneous labor without coercion, and noted that even in such a society, enforcement would be necessary to maintain social order against inevitable exceptions or non-economic motives like religious zeal, jealousy, or ambition. He argued that the socialist ideal of an egalitarian order simultaneously promising anarchy and freedom was contradictory; a planned, rational social order necessitates increasing coercion as it becomes more complex.

Against Marxist claims that the proletariat would represent the entire society, Kelsen asserted that granting political rights exclusively to the proletariat or its party was a "typical fiction" used by aristocratic and despotic rule, akin to a theocracy. He challenged the notion that a "true community will" would emerge, pointing to the intense divisions among socialist factions themselves.

For Kelsen, the dictatorship of the proletariat was a form of despotism opposed to democracy, predicated on an absolute value of justice, contrasting sharply with the critical and relativistic worldview of democracy. He emphasized that democracy, by entrusting power to the temporary majority, does not guarantee absolute good but rather presupposes and protects minorities, recognizing the relative value of all political beliefs. In democracy, political absolutism is rejected, and every political conviction must be prepared to yield ground to others.

He challenged Vladimir Lenin's call for the abolition of parliamentarism, pointing out that Lenin's arguments were flawed and that even the Soviet and Räte (council) systems were ultimately representative bodies with pyramidal structures. Kelsen argued that making workplaces the electoral unit would politicize economic production and jeopardize the economic system. He stated that direct democracy is impractical in modern developed nations, and attempts to tighten the link between public will and representatives would only lead to larger, not smaller, parliamentary systems.

Kelsen contended that the Marxist rejection of the majority principle, based on the idea that it is unsuitable for resolving class conflicts in a divided society, implies resolving such conflicts through "revolutionary violence" rather than peaceful, democratic adjustment. He argued that denying the majority principle is denying compromise, which is the practical approximation of an ideal consensus rooted in the idea of freedom to create social order.

He further criticized the Marxist contrast between "bourgeois democracy" (formal democracy) and "proletarian democracy" (social democracy promising equality of property). Kelsen asserted that the primary ideal of democracy is freedom, not equality. The historical struggle for democracy has been a struggle for political freedom and popular participation in legislation and administration. He saw the Bolshevik claim of realizing social democracy through a dictatorship as "true democracy" as an abuse of language, an attempt to substitute the concept of freedom with that of justice, and an unjust slur on the achievements of those who brought about modern democracy.

Kelsen observed that despite Marxist predictions, the proletariat did not become the overwhelming majority in developed democracies. Even in countries where socialist parties achieved power, the proletariat remained a minority. This factual disparity, he argued, led Marxist parties to abandon democratic ideals, turning towards absolute political dogmatism and the absolute rule of the party embodying that dogma, leading to dictatorship. He concluded that an absolute authority embodying an "absolute good" demands nothing but obedience, a premise that is antithetical to democracy.

In opposition to the absolutist worldview of Marxism, Kelsen posited that democracy presupposes a critical and relativistic worldview, requiring individuals to always be ready to yield space to others. In a democracy, opponents are politically recognized, their fundamental rights are protected, and conflicts are resolved through adjustments, not unconditional adoption of one side's views. For Kelsen, democracy is an expression of political relativism, standing in direct opposition to political absolutism. He asserted that democracy is the system most suitable for the political advancement of the proletariat, while also condemning German National Socialism (Nazism) as an anti-democratic movement alongside Russian Communism.

4.4. Distinction between State and Society

Kelsen's political philosophy also meticulously clarified the necessary delineation between the legal realm (the state) and the social and cultural sphere (society). While firmly endorsing the identity of law and state-meaning the state is essentially the legal order-Kelsen remained equally sensitive to the crucial need for society to maintain tolerance and actively encourage the discussion and debate of diverse philosophies, sociologies, theologies, metaphysics, and religions.

For Kelsen, culture and society provide the essential context for values, discussions of justice, and the development of varied cultural attributes. He recognized society's extensive province as a space for open discourse on topics such as religion, natural law, metaphysics, and the arts. Crucially, Kelsen believed that while discussions of justice, for example, were highly appropriate to the domain of society and culture, their direct and extensive dissemination within the realm of positive law was highly narrow and dubious.

He argued that for the science of law to progress effectively and respond to the geopolitical and domestic needs of the 20th century, it must maintain its objectivity by focusing solely on positive legal norms. This meant that the study of law must carefully and appropriately delineate its domain, ensuring it is not unduly influenced or conflated with the broader, more subjective discussions of societal values and justice. This clear separation aimed to prevent the law from being manipulated by ideological elements, thereby preserving its integrity as a rational and objective system.

5. Influence and Assessment

Hans Kelsen's profound contributions left an indelible mark on 20th-century legal and political thought, inspiring generations of scholars and sparking enduring intellectual debates. His work continues to be assessed and commemorated by institutions dedicated to preserving his legacy.

5.1. Academic Influence and Legacy

Kelsen's theories garnered widespread academic influence, particularly in Europe and Latin America, though less so in common-law countries. His ideas were further developed by numerous scholars, leading to the formation of distinct schools of thought. In his homelands, the "Vienna School" in Austria and the "Brno School" led by František Weyr in Czechoslovakia advanced his concepts, influencing figures like Adolf Julius Merkl and Alfred Verdross.

In the English-speaking world, Kelsen's influence is notably evident in the work of prominent legal philosophers such as H. L. A. Hart, John Gardner, Leslie Green, and Joseph Raz, often forming the basis for the "Oxford school" of jurisprudence. His ideas also drew "backhanded compliment[s]" through strenuous criticism from scholars like John Finnis. Other significant English-language commentators on Kelsen include Robert S. Summers, Neil MacCormick, and Stanley L. Paulson.

Kelsen's impact extended to Japan, where he significantly influenced the field of law. Scholars like Shiro Seimiya and Asao Otaka studied under Kelsen around 1925 and 1928, respectively, and their learning subsequently shaped legal education and institutions in Japan. Other Japanese jurists who were strongly influenced by Kelsen include Kisaburo Yokota, Toshiyoshi Miyazawa, Nobushige Ukai, Junichi Aomi, and Ryuichi Nagao. In 1934, American jurist Roscoe Pound lauded Kelsen as "unquestionably the leading jurist of the time."

5.2. Major Critiques and Debates

Kelsen's theories generated significant intellectual controversies throughout his lifetime and continue to be debated posthumously. One prominent example is the ongoing discussion surrounding his concept of the Grundnorm. Its closest antecedent is found in the writings of his colleague Adolf Julius Merkl, who developed a structural approach to understanding law based on the hierarchical relationship of norms. Kelsen assimilated Merkl's approach into his Pure Theory of Law, seeing the Grundnorm as indicating the logical regress of superior relationships between norms, ultimately leading to a norm superior to no other. It also represented the importance Kelsen ascribed to a fully centralized legal order.

A persistent debate has centered on whether Kelsen should be read as a Neo-Kantian, following his early engagement with Hermann Cohen's work in 1911. While Kelsen himself maintained he did not directly use Cohen's material in his 1911 book, he found Cohen's ideas attractive. This has led to an enduring scholarly debate about whether Kelsen became a Neo-Kantian or maintained his distinct non-Neo-Kantian stance. The Neo-Kantians often pressed Kelsen on whether the Grundnorm was strictly symbolic or had a concrete foundation, leading to a further division in interpretation: some viewed it as a hypothetical "as-if" construction in the vein of Hans Vaihinger, while others sought a practical reading, comparing it to a sovereign nation's federal constitution. Kelsen's own indications varied, with some Neo-Kantians asserting that later in life he largely accepted the symbolic reading in a Neo-Kantian context.

Another significant controversy involved Kelsen's prolonged debate with Carl Schmitt on questions of sovereignty and the guardian of the constitution. Kelsen staunchly defended the principle of the state's adherence to the rule of law above political considerations, contrasting sharply with Schmitt's view, which advocated for the priority of political fiat. Kelsen's 1931 essay, "Who Should Be the Guardian of the Constitution?", was a scathing reply to Schmitt, defending judicial review against executive authoritarianism. This debate polarized legal opinion throughout the 1920s and 1930s and extended for decades after Kelsen's death.

Following World War I and the Treaty of Versailles, Kelsen was deeply concerned by the perceived lack of accountability for political and military leaders. He dedicated much of his writing in the 1930s and 1940s to addressing this "historical inadequacy" of international law, ultimately contributing to the international precedent for establishing war crimes trials at Nuremberg and Tokyo after World War II. However, Kelsen's defense of these trials later drew explicit criticism from scholars like Joseph Raz.

During his American years, Kelsen also faced criticism from legal realists like Karl Llewellyn, who found his work "utterly sterile" outside its by-products, and from jurist Harold Laski.

A significant post-World War II criticism, particularly from some German legal scholars like Gustav Radbruch, argued that Kelsen's legal positivism, with its emphasis on the separation of law from morality, could be seen as having inadvertently paved the way for the "legal illegality" of Nazi laws. This critique suggested that strict positivism might hinder resistance to unjust laws. However, many scholars, including Kelsen's defenders, contend that this interpretation misrepresents Kelsen's intent. They argue that Kelsen's Pure Theory of Law was a scientific endeavor to understand law as it is, distinct from moral evaluation, precisely to prevent the arbitrary injection of ideological or political elements into legal discourse. Kelsen's own life and work, marked by his outspoken opposition to totalitarianism and his contributions to establishing international war crimes tribunals, underscore his commitment to the rule of law and justice, making such criticisms of his philosophy enabling Nazism largely misplaced. The debate between Kelsenian and Hartian forms of legal positivism continues to influence legal studies, distinguishing between Anglo-American and Continental approaches.

5.3. Contributions and Commemoration

Hans Kelsen's monumental contributions are preserved and promoted by several dedicated institutions. On the occasion of his 90th birthday, the Austrian federal government established the "Hans Kelsen-Institut" in Vienna on September 14, 1971, which became operational in 1972. Its primary task is to document the Pure Theory of Law and its dissemination both in Austria and internationally, as well as to encourage its continued development. The Institut publishes a book series and manages the rights to Kelsen's works, including editing and publishing several of his previously unpublished papers, such as General Theory of Norms (1979) and Secular Religion (2012). The Institut maintains an online database of his works. Its founding directors were Kurt Ringhofer and Robert Walter; Clemens Jabloner (since 1993) and Thomas Olechowski (since 2011) currently lead it.

In 2006, the Hans-Kelsen-Forschungsstelle (Hans Kelsen Research Center) was founded under Matthias Jestaedt at the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, later transferring to the Albert-Ludwigs-University of Freiburg in 2011. In cooperation with the Hans Kelsen-Institut, this center publishes a historical-critical edition of Kelsen's complete works, planned to exceed 30 volumes.

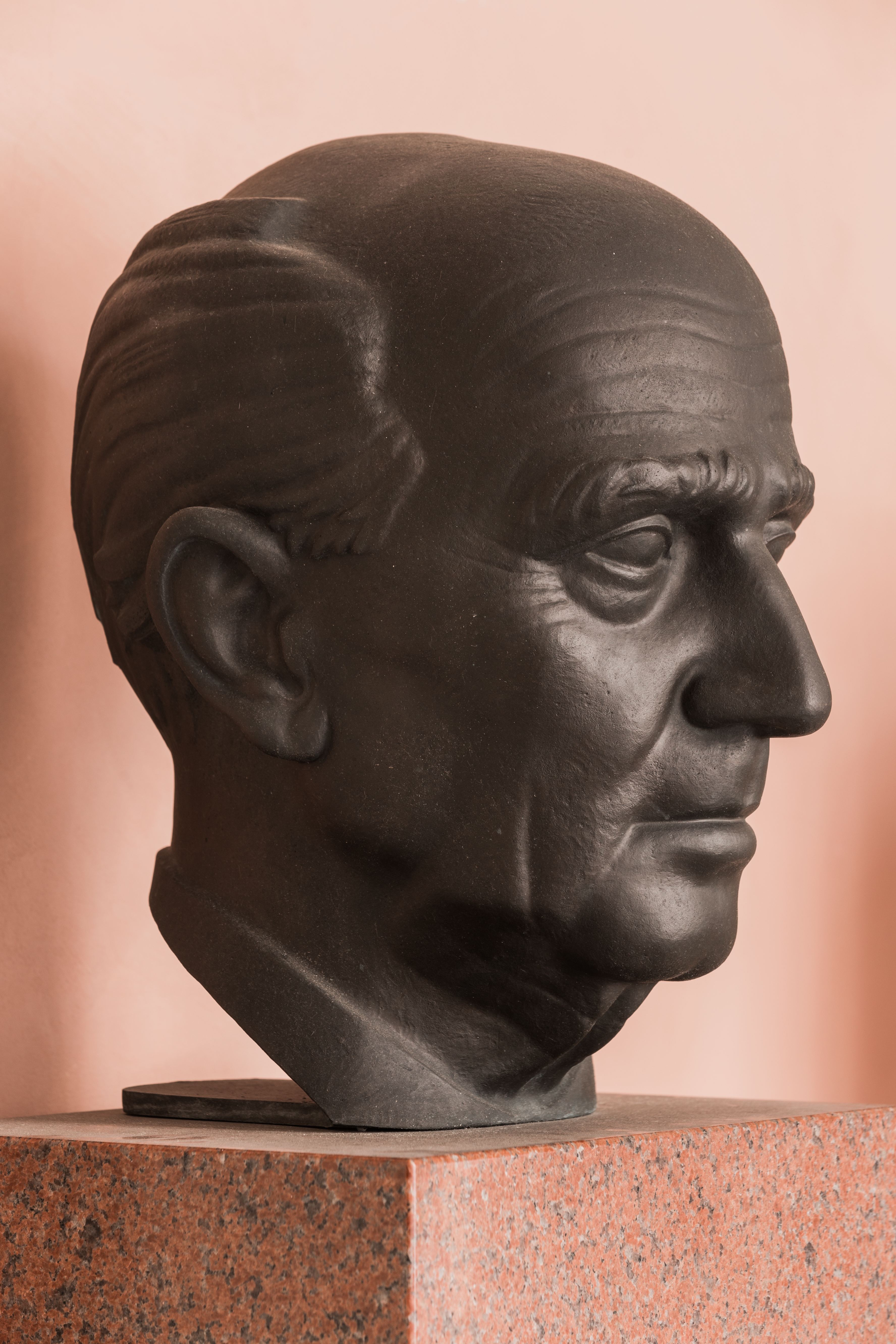

Various honors, awards, and biographical efforts further acknowledge Kelsen's profound academic contributions. A comprehensive biography by Thomas Olechowski, Hans Kelsen: Biographie eines Rechtswissenschaftlers (Hans Kelsen: Biography of a Legal Scientist), was published in 2020. A bust of Hans Kelsen is prominently displayed in the Arkadenhof of the University of Vienna, commemorating his enduring legacy.

6. Honours and Awards

- 1938: Honorary Member of the American Society of International Law

- 1953: Karl Renner Prize

- 1960: Feltrinelli Prize

- 1961: Grand Merit Cross with Star of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1961: Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- 1966: Ring of Honour of the City of Vienna

- 1967: Great Silver Medal with Star for Services to the Republic of Austria

- 1981: Kelsenstrasse in Vienna Landstraße (3rd District) named after him

7. Publications

- Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri (1905)

- Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre, entwickelt aus der Lehre vom Rechtssatze (1911)

- Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (1920)

- Sozialismus und Staat: Eine Untersuchung der politischen Theorie des Marxismus (1920)

- Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (1920, revised and enlarged edition 1929)

- Österreichisches Staatsrecht: Ein Grundriss entwicklungsgeschichtlich dargestellt (1923)

- Marx oder Lasalle : Wandlungen in der politischen Theorie des Marxismus (1924)

- Allgemeine Staatslehre (1925)

- Der soziologische und der juristische Staatsbegriff. Kritische Untersuchung des Verhältnisses von Staat und Recht (1928)

- Die philosophischen Grundlagen der Naturrechtslehre und des Rechtspositivismus (1928)

- Wer soll der Hüter der Verfassung sein? (1931)

- Reine Rechtslehre: Einleitung in die rechtswissenschaftliche Problematik (1934)

- Vergeltung und Kausalität: Eine soziologische Untersuchung (1941)

- Law and Peace in International Relations (1942)

- Society and Nature (1943)

- Peace Through Law (1944)

- General Theory of Law and State (1945; German original unpublished)

- The Political Theory of Bolshevism: A Critical Analysis (1948)

- The Law of the United Nations: a critical analysis of its fundamental problems (1950), with a supplement, Recent Trends in the Law of the United Nations (1951)

- Principles of International Law (1952, 2nd ed. 1966)

- Was ist Gerechtigkeit? (1953)

- "Foundations of Democracy" in Ethics (1955)

- Reine Rechtslehre, 2nd edition (1960; much expanded from 1934 and effectively a different book)

- Pure Theory of Law (1967; English translation of the 1960 edition)

- Essays in Legal and Moral Philosophy (1973; posthumously published)

- Allgemeine Theorie der Normen (1979; posthumously published)

- General Theory of Norms (1990; English translation of the 1979 edition)

- The Essence and Value of Democracy (2013; English translation of the 1929 version of Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie)

- Secular Religion: A Polemic against the Misinterpretation of Modern Social Philosophy, Science, and Politics as "New Religions" (2012, revised edition 2017; posthumously published, written in English)