1. Early Life

Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich's early life was defined by the turbulent aftermath of the Russian Revolution, leading to his birth and upbringing in exile.

### Birth and Childhood ###

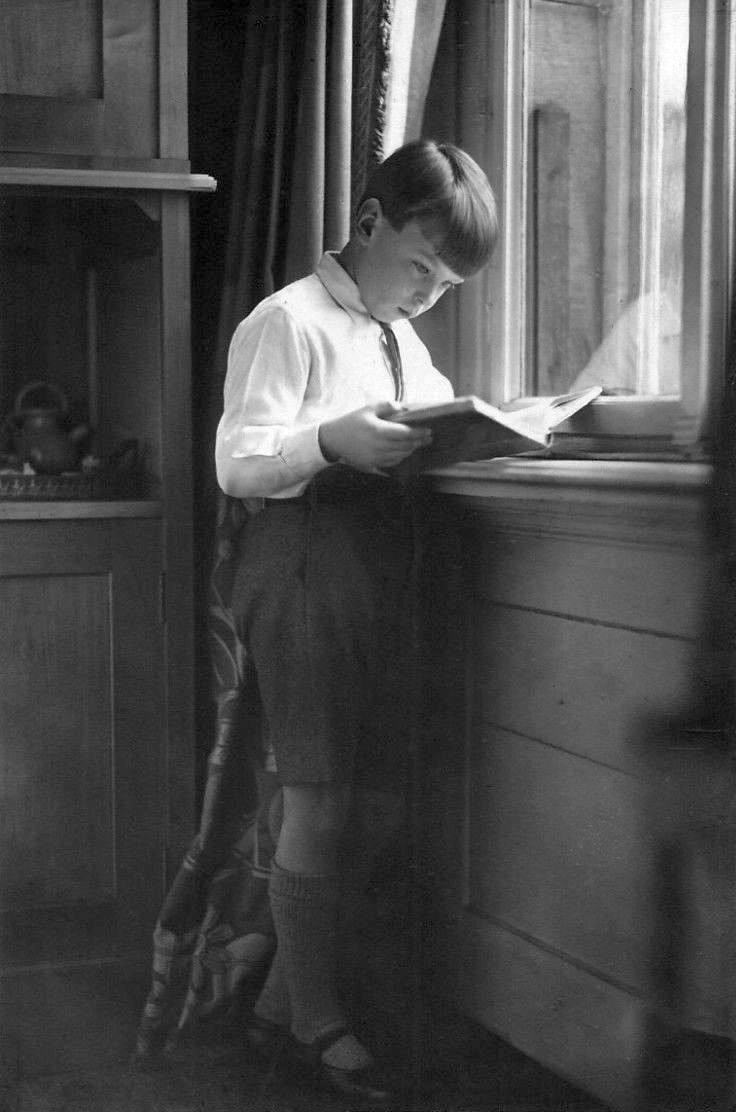

Vladimir was born as Prince Vladimir Kirillovich of Russia on August 30, 1917, in Porvoo, within the then Grand Duchy of Finland. He was the only son of Grand Duke Cyril Vladimirovich and Grand Duchess Viktoria Feodorovna (née Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha). His parents were first cousins, both being grandchildren of Emperor Alexander II. Vladimir's paternal grandparents were Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia and Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, while his maternal grandparents were Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia. He was described as a large and handsome child, noted for his resemblance to his granduncle, Alexander III of Russia.

His family had fled to Finland following the collapse of the Russian Empire and the Russian Revolution. In 1920, his family departed from Finland, relocating to Coburg, Germany. On August 8, 1922, his father, Cyril, declared himself "Curator of the Russian throne." Two years later, on August 31, 1924, Cyril went further by assuming the title of "Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias." Concurrently with his father's assumption of the Imperial title, Vladimir was granted the title of Tsesarevich (heir apparent) and Grand Duke with the style of Imperial Highness (Его Императорское ВысочествоYego Imperatorskoye VysochestvoRussian). In 1930, his family left Germany for Saint-Briac-sur-Mer, France, where his father established his "court-in-exile."

### Education and Early Career ###

In the 1930s, Vladimir spent a period living in England, where he pursued studies at the University of London. During this time, he also worked at the Blackstone agricultural equipment factory located in Lincolnshire. Following his time in England, he returned to France, moving to Brittany, where he settled as a landowner and farmer.

2. Headship of the Imperial Family and World War II

This section details Grand Duke Vladimir's assumption of the headship of the Imperial Family of Russia and his complex actions during World War II, including his refusal to explicitly support Nazi Germany and his subsequent internment.

### Succession to Headship ###

Upon the death of his father on October 12, 1938, Vladimir assumed the Headship of the Imperial Family of Russia. In the same year, he was approached with a suggestion to become the regent of Carpatho-Ukraine. However, Vladimir rejected this proposal, stating his unwillingness to contribute to the dissolution of Russia, indicating his continued adherence to the idea of a unified Russian state.

### Activities during World War II ###

During World War II, Vladimir was residing in Saint-Briac-sur-Mer in Brittany, France. On June 26, 1941, shortly after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, he issued a statement expressing his view that "Germany and almost all the nations of Europe have declared a crusade against Communism and Bolshevism." In this statement, he appealed to "all the faithful and loyal sons of our Homeland" to do what they could "to bring down the Bolshevik regime and to liberate our Homeland from the terrible yoke of Communism." This demonstrated his strong anti-communist stance and his hope for the overthrow of the Soviet government.

Despite this early statement, in 1942, Vladimir refused a direct request from Nazi Germany to issue a manifesto calling on Russian émigrés to actively support Germany's war efforts against the Soviet Union. As a consequence of his refusal, Vladimir and his entourage were placed in an internment camp at Compiègne by the Nazis.

In 1944, as the war progressed and Allied forces posed a threat from the coast, the Wehrmacht (German army) relocated Vladimir's family further inland. They were initially moved towards Paris, then rerouted to Vittel. When Vittel also became unsafe, they were transferred to Germany. Vladimir resided in a castle in Amorbach, Bavaria, which belonged to the husband of his elder sister, Maria Kirillovna of Russia, until 1945.

Following Germany's defeat, Vladimir feared capture by the advancing Soviet forces. This prompted his urgent relocation, first to Austria and then to the border of Liechtenstein. He attempted to cross the border with the army of General Boris Smyslovsky, a Russian émigré who had collaborated with the Germans, but both Liechtenstein and Switzerland denied him exit visas. Consequently, he was forced to remain in Austria, settling in the American occupation zone. His maternal aunt, Infanta Beatrice of Orléans-Borbon, played a crucial role in securing a Spanish visa for him, enabling him to subsequently live with her in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain.

3. Post-War Life and Succession Disputes

This section examines Grand Duke Vladimir's life in exile after World War II, focusing on his primary residences and the significant controversies surrounding his marriage and its implications for the succession to the Russian throne.

### Exile and Residences ###

After the conclusion of World War II, Grand Duke Vladimir spent the majority of his time residing in Madrid, Spain. He also maintained frequent stays at his property in Brittany, France, and occasionally visited Paris.

### Marriage and Legitimacy Controversy ###

Vladimir married Princess Leonida Georgievna Bagration-Moukhransky on August 13, 1948, in Lausanne, Switzerland. This marriage became a focal point of controversy regarding the legitimacy of the succession to the Russian throne. Pre-revolutionary Romanov house laws stipulated that only those born of an "equal marriage" between a Romanov dynast and a member of a "royal or sovereign house" were included in the Imperial line of succession to the Russian throne. Children resulting from morganatic marriages were explicitly deemed ineligible to inherit the throne or dynastic status.

Princess Leonida belonged to the House of Bagration-Mukhrani, a branch of the family that had ruled as kings in Georgia from the medieval era until the early 19th century. However, no male-line ancestor of hers had reigned as a king in Georgia since 1505, and her specific branch of the Bagrations had been naturalized among the non-ruling Russian nobility after Georgia's annexation by the Russian Empire in 1801. Despite this, the royal status of the broader House of Bagration had been recognized by Russia in the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk. Vladimir Kirillovich, asserting his position as the claimed head of the Russian Imperial House, formally confirmed this recognition on December 5, 1946. However, the last reigning emperor, Nicholas II, had previously considered a marriage involving Princess Tatiana Constantinova to this family in 1911 as morganatic. This conflicting precedent sparked a debate over whether Vladimir's marriage to Leonida was an "equal" or a "morganatic" union. The resolution of this debate was crucial, as it would determine whether his claim to the Imperial throne could validly pass to his only daughter, Maria, or if it would devolve to another dynast, or cease altogether upon his death.

#### Views of Other Romanov Branches ####

The controversy surrounding Vladimir's marriage intensified due to the opposition from other branches of the Romanov family. In 1969, the heads of three other prominent branches-Prince Vsevolod Ioannovich (representing the Konstantinovichi line), Prince Roman Petrovich (of the Nikolaevichi line), and Prince Andrei Alexandrovich (from the Mihailovichi line)-addressed a letter to Vladimir. In their communication, they explicitly asserted that the dynastic status of his daughter, Maria, was no different from that of their own children. They argued that his wife, Leonida, was of no higher status than the wives of the other Romanov princes, thereby implicitly rejecting the equality of Vladimir's marriage and, by extension, the dynastic claims of his daughter. For example, Roman Petrovich had two sons born to Countess Prascovia Sheremetyev, and Andrei Alexandrovich had two sons with Donna Elisabeth Ruffo of a Russian branch of the Princes di San Sant' Antimo, marriages that were widely regarded by many as morganatic.

### Later Activities and Visit to Russia ###

In 1952, Grand Duke Vladimir publicly urged the Western powers to initiate a war against the Soviet Union, a testament to his unwavering anti-communist convictions and his hopes for the restoration of a monarchical Russia.

On December 23, 1969, Vladimir issued a highly controversial decree. This declaration stated that in the event he predeceased the living male Romanovs whom he recognized as dynasts, his daughter, Maria, would then assume the title of "Curatrix of the Imperial Throne." This move was widely interpreted as an attempt by Vladimir to ensure that the succession to the imperial headship remained within his direct line, even in the absence of a male heir. Predictably, the heads of the other Romanov branches vehemently opposed this decree, declaring Vladimir's actions to be illegal and contrary to established Romanov house laws.

A significant moment in his later life occurred in November 1991, when Vladimir made a historic visit to St. Petersburg, Russia. He was invited by its then-Mayor, Anatoly Sobchak, marking the first time he had set foot in his ancestral homeland. During this visit, while he stated he was not actively seeking the throne, he also did not explicitly deny his claim to it, maintaining a nuanced public stance.

4. Death and Legacy

This section details the circumstances of Grand Duke Vladimir's death, the complex succession disputes that immediately followed, and provides a broader historical assessment of his role and the criticisms leveled against him.

### Death and Funeral ###

Grand Duke Vladimir died on April 21, 1992, in Miami, United States. He suffered a heart attack while addressing a gathering of Spanish-speaking bankers and investors at Northern Trust Bank. Following his death, his body was returned to Russia, a significant event as he was the first Romanov to be honored with a burial there, specifically in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, since before the Russian Revolution.

The funeral itself was a grand affair, but news reports were careful to interpret its symbolism. The press noted that the funeral "was regarded by civic and Russian authorities as an obligation to the Romanov family rather than a step toward restoration of the monarchy." A government spokesperson reportedly described it as "part of our atonement." Furthermore, a specific issue arose concerning the inscription on his tombstone. As he was only a great-grandson of a recognized Russian emperor, his self-proclaimed title of "Grand Duke of Russia" presented a dilemma regarding what formal title to engrave on his grave.

### Disputed Succession to the Russian Imperial Headship ###

After Grand Duke Vladimir's death, the question of succession to the headship of the Imperial Family of Russia immediately became a point of contention. His only daughter, Maria Vladimirovna, asserted her claim to the headship based on her branch's interpretation of the Russian house laws, particularly her father's controversial 1969 decree.

However, this claim was strongly disputed by Prince Nicholas Romanov, who belonged to the Nikolaevichi branch of the Romanov family. Prince Nicholas had already been chosen as the president of the self-styled "Romanov Family Association" prior to Grand Duke Vladimir's passing. Consequently, two competing claims to the headship of the Romanov family emerged, with Maria Vladimirovna and Nicholas Romanov representing different interpretations of dynastic succession and family law.

### Holstein-Gottorp Ducal Title Succession ###

In addition to his claims to the Russian imperial headship, Grand Duke Vladimir also held the ducal title of Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, a title that had been associated with the head of the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov since 1773. The succession to the Holstein-Gottorp ducal title is governed by Salic law, which strictly dictates inheritance through the male line. Following Vladimir's death, the succession to this title became a subject of discussion. It was generally considered to have passed to his second cousin once removed, Prince Paul Ilyinsky (Pavel Dmitrievich Romanov-Ilyinsky). Vladimir was notably the last individual to actively use the Holstein-Gottorp ducal title.

### Historical Assessment and Criticisms ###

Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich's historical significance lies primarily in his role as a claimant to the Russian imperial throne in exile during a period when Russia underwent profound political and social transformations. He served as a symbolic figurehead for monarchist movements, embodying the continuity of the Romanov dynasty. His life and actions, however, were not without significant criticism.

One of the most persistent criticisms centered on his interpretation of Romanov house laws, particularly regarding the concept of "equal marriage." His marriage to Princess Leonida Bagration-Moukhransky was widely regarded by other branches of the Romanov family as morganatic, leading to their rejection of his daughter Maria's dynastic claims. His controversial 1969 decree, unilaterally designating Maria as "Curatrix of the Imperial Throne," was viewed by many as an attempt to ensure the succession remained within his direct line, further exacerbating internal family divisions and being deemed illegal by opposing Romanov factions.

His political statements and actions during World War II also drew scrutiny. While he was interned by the Nazis for refusing to endorse their war against the Soviet Union, his earlier statement on June 26, 1941, calling for Russian émigrés to "bring down the Bolshevik regime" suggested a complex and at times opportunistic alignment with forces opposed to the Soviet state. His later call in 1952 for Western powers to wage war against the Soviet Union further highlighted his unwavering, yet controversial, anti-communist stance.

Ultimately, his historic visit to Russia in 1991, while a poignant moment for the exiled family, did not lead to any restoration of the monarchy. This reinforced the perception of his role as primarily a symbolic one for a monarchist movement that, despite its continuity, lacked significant popular support for a return to imperial rule.

5. Honours

Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich received various official honors and decorations during his lifetime, reflecting his royal lineage and position.

- Prussian Imperial and Royal Family: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle.

6. Ancestry

| 1. Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich of Russia | |

|---|---|

| Parents | |

| 2. Grand Duke Cyril Vladimirovich of Russia | 3. Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Paternal Grandparents | |

| 4. Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia | 5. Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

| Maternal Grandparents | |

| 6. Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | 7. Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia |

| Paternal Great-Grandparents (from 4 & 5) | |

| 8. Alexander II of Russia | 9. Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine |

| 10. Frederick Francis II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | 11. Princess Augusta Reuss of Köstritz |

| Maternal Great-Grandparents (from 6 & 7) | |

| 12. Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | 13. Queen Victoria |

| 14. Alexander II of Russia | 15. Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine |