1. Overview

Edith Newbold Wharton (born Edith Newbold Jones; January 24, 1862 - August 11, 1937) was a distinguished American novelist, short story writer, and designer. Drawing on her intimate knowledge of the elite New York society of the Gilded Age, Wharton's works realistically portray the lives, morals, and social constraints of the upper class. Her literary contributions earned her significant acclaim, including the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921 for her novel The Age of Innocence, making her the first woman to receive this honor. She was also nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature multiple times and was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1996. Beyond her fiction, Wharton was a prolific writer of non-fiction, including travelogues, essays on design, and an autobiography. She was also a notable landscape and interior designer, with her estate, The Mount, serving as a prime example of her design principles. During World War I, Wharton dedicated extensive efforts to humanitarian work in France, for which she was awarded the Legion of Honour. Her enduring legacy lies in her sharp social commentary, psychological depth, and mastery of prose, which continue to influence American literature.

2. Biography

Edith Wharton's life journey spanned from her privileged upbringing in New York's elite society to her later years as an acclaimed author and humanitarian in France.

2.1. Early Life and Background

Edith Wharton's formative years were shaped by her affluent family background and the strict social conventions of 19th-century New York.

2.1.1. Birth and Family

Edith Newbold Jones was born on January 24, 1862, in New York City, at her family's brownstone located at 14 West Twenty-third Street. Her parents were George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander. Within her close circle of friends and family, she was affectionately known as "Pussy Jones". She had two older brothers, Frederic Rhinelander and Henry Edward. Frederic married Mary Cadwalader Rawle, and their daughter, Beatrix Farrand, later became a notable landscape architect. Edith was baptized on April 20, 1862, which was Easter Sunday, at Grace Church.

The Jones family, Wharton's paternal lineage, was exceedingly wealthy and held a prominent social standing, having amassed their fortune through real estate investments. It is said that the popular saying "keeping up with the Joneses" originated in reference to her father's family. She was also related to the prestigious Rensselaers family, one of the oldest patroon families who had received land grants from the former Dutch government of New York and New Jersey. Her father's first cousin was Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, a prominent socialite. On her maternal side, her great-grandfather was Ebenezer Stevens, a hero and general of the American Revolutionary War, after whom Fort Stevens in New York was named.

Wharton was born during the American Civil War. However, in her descriptions of family life, she rarely mentioned the war, except to note that their subsequent travels to Europe were influenced by the depreciation of American currency.

2.1.2. Education

From 1866 to 1872, when Edith was a child, the Jones family embarked on extensive travels across Europe, visiting countries such as France, Italy, Germany, and Spain. During these travels, she received her education from private tutors and governesses, becoming fluent in French, German, and Italian. At the age of nine, while the family was at a spa in the Black Forest, she contracted typhoid fever and nearly died. After returning to the United States in 1872, the family divided their time between winters in New York City and summers in Newport, Rhode Island.

Edith often expressed dissatisfaction with the limited education provided to young girls of her era, which typically focused on preparing them for advantageous marriages and social display at balls and parties. She viewed these societal expectations as superficial and oppressive. To supplement her formal education, she voraciously read from her father's extensive library, which included works of classics, philosophy, history, and poetry. Among the authors she read were Daniel Defoe, John Milton, Thomas Carlyle, Alphonse de Lamartine, Victor Hugo, Jean Racine, Thomas Moore, Lord Byron, William Wordsworth, John Ruskin, and Washington Irving. Her mother, however, strictly forbade her from reading novels until she was married, a command Edith dutifully observed.

Wharton's intellectual development was also significantly influenced by contemporary thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, Charles Darwin, Friedrich Nietzsche, T. H. Huxley, George Romanes, James Frazer, and Thorstein Veblen, whose ideas contributed to her ethnographic style of novelization. Despite her mother's restrictions, she developed a deep passion for the poetry of Walt Whitman. Interestingly, American children's stories containing slang, by popular authors like Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Joel Chandler Harris, were prohibited in her childhood home. While she was permitted to read Louisa May Alcott, Wharton preferred the imaginative tales of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby.

2.2. Early Writing and Career Beginnings

Edith Wharton's early life saw her first attempts at writing, her formal entry into society, and her significant early marriage.

2.2.1. Early Literary Attempts

Wharton began writing and telling stories at a very young age. From the age of four or five, when her family moved to Europe, she started what she called "making up" stories. She would invent narratives for her family, often walking with an open book and turning its pages as if reading, while improvising a story aloud. She attempted to write her first novel at the age of 11, but her mother's criticism discouraged her, leading her to focus on poetry instead.

At 15, her first published work appeared: a translation of the German poem "Was die Steine Erzählen" ("What the Stones Tell") by Heinrich Karl Brugsch, for which she received 50 USD. Her family, however, disapproved of her name appearing in print, as writing was not considered a proper occupation for a woman of her social standing. Consequently, the poem was published under the name of a friend's father, E. A. Washburn, a cousin of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was a supporter of women's education. In 1877, also at the age of 15, she secretly wrote a novella titled Fast and Loose. The following year, in 1878, her father arranged for a private publication of Verses, a collection comprising two dozen original poems and five translations. Wharton also published a poem under a pseudonym in the New York World in 1879, and in 1880, five of her poems were anonymously published in the Atlantic Monthly, a prominent literary magazine. Despite these early successes, she received little encouragement from her family or social circle. She continued to write but did not publish anything further until her poem "The Last Giustiniani" appeared in Scribner's Magazine in October 1889. Her first short story, "Mrs. Manstey's View," was published in 1891, though it achieved little success, and it took her over a year to publish another.

2.2.2. Social Debut and Marriage

Between 1880 and 1890, Wharton temporarily set aside her writing pursuits to immerse herself in the social rituals of the New York upper classes. During this period, she keenly observed the societal changes occurring around her, which later became rich material for her fiction. She officially made her social debut in 1879. A notable event during her debutante season was a December dance hosted by social matron Anna Morton, where Wharton was allowed to bare her shoulders and wear her hair up for the first time.

She began a courtship with Henry Leyden Stevens, the son of Paran Stevens, a wealthy hotelier and real estate investor from rural New Hampshire. Their engagement was announced in August 1882, but it was abruptly called off the month before the wedding, reportedly due to the disapproval of the Jones family. Following this, Wharton's mother, Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander Jones, relocated to Paris in 1883, where she resided until her death in 1901.

On April 29, 1885, at the age of 23, Edith married Edward Robbins (Teddy) Wharton, who was 12 years her senior, at the Trinity Chapel Complex in Manhattan. Teddy, hailing from a well-established Boston family, was a sportsman and a gentleman of her social class who shared her passion for travel. The couple initially established their home at Pencraig Cottage in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1893, they purchased Land's End, another property in Newport, for 80.00 K USD, and moved in. Wharton personally oversaw the decoration of Land's End, collaborating with designer Ogden Codman. In 1897, the Whartons acquired their New York residence at 884 Park Avenue. From the time of her marriage onward, three primary interests came to define Wharton's life: American houses, writing, and Italy.

2.3. Life Abroad and Travel

Edith Wharton's extensive travels and prolonged periods living abroad significantly influenced her perspective and literary output. She crossed the Atlantic Ocean 60 times throughout her life, primarily visiting Italy, France, and England, but also venturing to Morocco. These journeys inspired many of her travel books, including Italian Backgrounds, A Motor-Flight through France, and In Morocco.

Her husband, Edward Wharton, shared her love for travel, and for many years, they spent at least four months annually abroad, mainly in Italy, often accompanied by their friend, Egerton Winthrop. In 1888, when Wharton was 26, she, Edward, and their friend James Van Alen embarked on a four-month cruise through the Aegean islands, which cost the Whartons 10.00 K USD. During this trip, she maintained a travel journal that was later published as The Cruise of the Vanadis, now recognized as her earliest known travel writing.

As her marriage deteriorated, Wharton made the decision to move permanently to France. She initially resided at 53 Rue de Varenne in Paris, in an apartment owned by George Washington Vanderbilt II. After World War I, seeking tranquility away from Paris, she settled at Pavillon Colombe, an 18th-century house situated on seven acres of land 10 mile north of Paris in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt. She spent her summers and autumns there for the remainder of her life, while her winters and springs were spent on the French Riviera at Sainte Claire du Vieux Chateau in Hyères. Following the war, she also traveled to Morocco as the guest of Resident General Hubert Lyautey, a trip that resulted in her book In Morocco, where she praised the French administration, Lyautey, and his wife.

During the post-war years, she divided her time between Hyères and Provence, where she completed The Age of Innocence in 1920. She returned to the United States only once after the war, in 1923, to receive an honorary doctorate from Yale University.

2.4. Domestic Life and Estates

Edith Wharton's personal life was deeply intertwined with her residences, reflecting her keen interest in design and her role as a prominent hostess. After her marriage to Edward Wharton, they established their first home at Pencraig Cottage in Newport. In 1893, they acquired Land's End, another property in Newport, for 80.00 K USD. Wharton found the main house "incurably ugly" upon purchase and invested thousands more to renovate its facade, decorate the interior, and landscape the grounds, with the assistance of designer Ogden Codman. In 1897, they also purchased a New York home at 884 Park Avenue.

In 1902, Wharton designed The Mount, her renowned estate in Lenox, Massachusetts, which stands today as a testament to her design principles. It was at The Mount that she penned several of her novels, including The House of Mirth (1905), one of her early chronicles of life in old New York. The estate served as a vibrant hub for American literary society, where she entertained many prominent figures, including her close friend, novelist Henry James, who famously described The Mount as "a delicate French chateau mirrored in a Massachusetts pond." Despite her frequent and lengthy travels in Europe with friends like Egerton Winthrop, The Mount remained her primary residence until 1911. During her time there and while traveling abroad, she was often driven to appointments by her long-time chauffeur and friend, Charles Cook, a native of nearby South Lee, Massachusetts.

Wharton's expertise in design extended beyond her personal residences. She authored several influential books on the subject, including her first major published work, The Decoration of Houses (1897), co-authored with Ogden Codman. Another notable work in this genre is the richly illustrated Italian Villas and Their Gardens (1904), which featured illustrations by Maxfield Parrish.

2.5. Personal Relationships and Divorce

Edith Wharton's personal life was marked by complex relationships, most notably her marriage and subsequent divorce, as well as significant friendships with leading intellectuals of her time.

Her marriage to Edward Robbins (Teddy) Wharton, which lasted 28 years, ended in divorce in 1913. From the late 1880s until 1902, Teddy suffered from chronic depression, which led to a cessation of their extensive travels. His mental condition became more debilitating over time, leading them to reside almost exclusively at their estate, The Mount. During these years, Wharton herself reportedly experienced periods of asthma and depression. In 1908, with Teddy's mental condition deemed incurable, Wharton began an affair with Morton Fullerton, an author and foreign correspondent for The Times of London, with whom she found a significant intellectual connection. The divorce from Edward in 1913 coincided with a period of harsh literary criticism she received from the naturalist school of writers.

Wharton maintained friendships and intellectual exchanges with many prominent figures of her era. Among her guests were renowned writers such as Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Jean Cocteau, and André Gide. She also counted Theodore Roosevelt, Bernard Berenson, and Kenneth Clark as valued friends. A particularly notable, though famously unsuccessful, encounter was her meeting with F. Scott Fitzgerald, described by editors of her letters as "one of the better known failed encounters in the American literary annals." Her long-time friend, Walter Van Rensselaer Berry, who was then president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Paris, was one of the few foreigners allowed to accompany her to the front lines during World War I. Wharton was fluent in French, Italian, and German, and many of her books were published in both French and English, reflecting her deep engagement with European culture.

2.6. World War I Efforts

When World War I erupted, Edith Wharton was preparing for a summer vacation. However, instead of fleeing Paris as many did, she returned to her apartment on the Rue de Varenne and for four years became a tireless and ardent supporter of the French war effort. In August 1914, one of her initial endeavors was to open a workroom for unemployed women, providing them with food and a daily wage of one franc. This initiative, which began with 30 women, quickly expanded to 60, and their sewing business flourished.

When the Germans invaded Belgium in the fall of 1914, leading to a flood of Belgian refugees into Paris, Wharton was instrumental in establishing the American Hostels for Refugees. This organization provided shelter, meals, and clothing to the displaced and eventually created an employment agency to help them find work. She successfully raised over 100.00 K USD on their behalf. In early 1915, she further organized the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee, which offered refuge to nearly 900 Belgian children who had fled their homes due to German bombings.

Aided by her influential connections within the French government, Wharton and her long-time friend, Walter Berry, were among the few foreigners in France granted permission to travel to the front lines during the war. They undertook five journeys between February and August 1915. Wharton documented these experiences in a series of articles initially published in Scribner's Magazine, which were later compiled into the book Fighting France: From Dunkerque to Belfort, becoming an American bestseller. Traveling by car, Wharton and Berry drove through the war zone, witnessing numerous devastated French villages. She visited the trenches and was often within earshot of artillery fire, noting, "We woke to a noise of guns closer and more incessant, and when we went out into the streets, it seemed as if, overnight, a new army had sprung out of the ground."

Throughout the war, Wharton remained deeply involved in charitable efforts, assisting refugees, the injured, the unemployed, and the displaced. She was lauded as a "heroic worker on behalf of her adopted country." In recognition of her dedication to the war effort, Raymond Poincaré, then President of France, appointed her Chevalier of the Legion of Honour on April 18, 1916, the country's highest award. Her relief work also included setting up workrooms for unemployed French women, organizing concerts to provide income for musicians, raising tens of thousands of dollars for the war effort, and establishing tuberculosis hospitals. In 1915, Wharton edited The Book of the Homeless, a charity benefit volume that featured essays, art, poetry, and musical scores by many prominent contemporary European and American artists, including Henry James, Joseph Conrad, William Dean Howells, Anna de Noailles, Jean Cocteau, and Walter Gay. Wharton proposed the book to her publisher, Scribner's, managed the business arrangements, secured contributors, and translated the French entries into English. Theodore Roosevelt contributed a two-page introduction, commending Wharton's efforts and urging Americans to support the war.

Despite her extensive humanitarian work, Wharton continued her own literary pursuits, writing novels, short stories, and poems, while also reporting for The New York Times and maintaining a vast correspondence. She actively urged Americans to support and enter the war. During this period, she wrote the popular romantic novel Summer (1917), the war novella The Marne (1918), and A Son at the Front (written in 1919, published in 1923). When the war concluded, she observed the Victory Parade from a friend's apartment balcony on the Champs Élysées. After four years of intense effort, she decided to leave Paris for the quiet of the countryside.

Wharton was a committed supporter of French imperialism, describing herself as a "rabid imperialist," and the war further solidified her political views. After the war, her travels to Morocco as the guest of Resident General Hubert Lyautey resulted in the book In Morocco, which expressed praise for the French administration, Lyautey, and particularly his wife.

2.7. Later Years and Recognition

Edith Wharton's later years were marked by continued literary productivity, significant critical acclaim, and numerous honors.

2.7.1. Later Life and Honors

Her novel The Age of Innocence, published in 1920, was awarded the 1921 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, making Edith Wharton the first woman to win this prestigious award. Notably, the three fiction judges-literary critic Stuart P. Sherman, literature professor Robert Morss Lovett, and novelist Hamlin Garland-had initially voted to award the prize to Sinclair Lewis for his satirical novel Main Street. However, Columbia University's advisory board, under the leadership of conservative university president Nicholas Murray Butler, overturned their decision and granted the prize to The Age of Innocence.

Wharton received further international recognition through nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1927, 1928, and 1930. In 1923, she received an honorary doctorate from Yale University, and in 1930, she was inducted as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Wharton was a friend and confidante to many prominent intellectuals of her time. Henry James, Sinclair Lewis, Jean Cocteau, and André Gide were among her guests at various times. Theodore Roosevelt, Bernard Berenson, and Kenneth Clark were also highly valued friends. A particularly notable, though famously unsuccessful, encounter was her meeting with F. Scott Fitzgerald, described by the editors of her letters as "one of the better known failed encounters in the American literary annals." Wharton was fluent in French, Italian, and German, and many of her books were published in both French and English.

2.7.2. Autobiography

In 1934, Wharton's autobiography, A Backward Glance, was published. According to Judith E. Funston, writing on Edith Wharton in American National Biography, the autobiography is most notable for what it omits: her criticisms of her mother, Lucretia Jones; the difficulties in her marriage with Teddy; and her affair with Morton Fullerton. These details did not come to light until her papers, deposited in Yale's Beinecke Rare Book Room and Manuscript Library, were opened in 1968.

2.8. Death

On June 1, 1937, Edith Wharton was at her French country home, Le Pavillon Colombe, which she shared with architect and interior decorator Ogden Codman. She was working on a revised edition of The Decoration of Houses when she suffered a heart attack and collapsed.

She died of a stroke on August 11, 1937, at 5:30 p.m., at Le Pavillon Colombe, her 18th-century house on Rue de Montmorency in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt. Her death was not immediately known in Paris. At her bedside was her friend, Mrs. Royall Tyler. Wharton was buried in the American Protestant section of the Cimetière des Gonards in Versailles, France. Her burial was conducted "with all the honors owed a war hero and a chevalier of the Legion of Honor," and a group of approximately one hundred friends sang a verse of the hymn 'O Paradise'.

3. Literary Career

Edith Wharton's literary career was marked by her prolific output, distinctive writing style, and profound thematic explorations that contributed significantly to American literature.

3.1. Writing Style and Themes

Wharton's novels are characterized by her subtle use of dramatic irony and her keen ability to critique the upper-class society of the late 19th century, particularly evident in works like The House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence. Her writing often explored themes such as "social and individual fulfillment, repressed sexuality, and the manners of old families and the new elite." She delved into the "extremes and anxieties of the Gilded Age," examining how social mores and the need for reform impacted individuals.

A key recurring theme in Wharton's fiction is the intricate relationship between a house as a physical space and its connection to the characteristics and emotions of its inhabitants. Maureen Howard, editor of Edith Wharton: Collected Stories, emphasizes that for Wharton, houses were "never mere settings," but rather "extended imagery of shelter and dispossession," highlighting their "confinement and their theatrical possibilities."

Wharton's writings frequently featured characters who were versions of her own mother, Lucretia Jones. Biographer Hermione Lee described these portrayals as "one of the most lethal acts of revenge ever taken by a writing daughter." In her memoir, A Backward Glance, Wharton depicted her mother as indolent, spendthrift, censorious, disapproving, superficial, icy, dry, and ironic. Other recurring themes in her short stories include confinement and attempts at freedom, the morality of the author, critiques of intellectual pretension, and the "unmasking" of truth.

3.2. Influences

Edith Wharton's intellectual and literary development was shaped by a diverse range of influences, from the classics she read in her father's library to contemporary philosophical and scientific thought. While American children's stories containing slang, by popular authors such as Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Joel Chandler Harris, were forbidden in her childhood home, she was permitted to read Louisa May Alcott. However, Wharton preferred the imaginative works of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby.

Her mother's prohibition against reading novels until marriage led Wharton to extensively explore other genres. She famously stated that she "read everything else but novels until the day of my marriage." This included a vast array of classics, philosophy, history, and poetry from her father's library. Among the authors she read were Daniel Defoe, John Milton, Thomas Carlyle, Alphonse de Lamartine, Victor Hugo, Jean Racine, Thomas Moore, Lord Byron, William Wordsworth, John Ruskin, and Washington Irving.

Biographer Hermione Lee noted that Wharton effectively "read herself out of Old New York" through her intellectual pursuits. Her influences extended to prominent thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, Charles Darwin, Friedrich Nietzsche, T. H. Huxley, George Romanes, James Frazer, and Thorstein Veblen, whose ideas contributed to her ethnographic approach to novelization. Additionally, Wharton developed a particular passion for the poetry of Walt Whitman.

3.3. Major Works

Despite not publishing her first novel until she was forty, Edith Wharton became an extraordinarily productive writer. Her extensive bibliography includes 15 novels, seven novellas, and 85 short stories. She also published poetry, books on design, travelogues, literary and cultural criticism, and a memoir.

3.3.1. Novels

Edith Wharton's major novels often explore the complexities of American society, particularly the upper class, and its impact on individual lives. Her notable novels include:

- The Valley of Decision, 1902

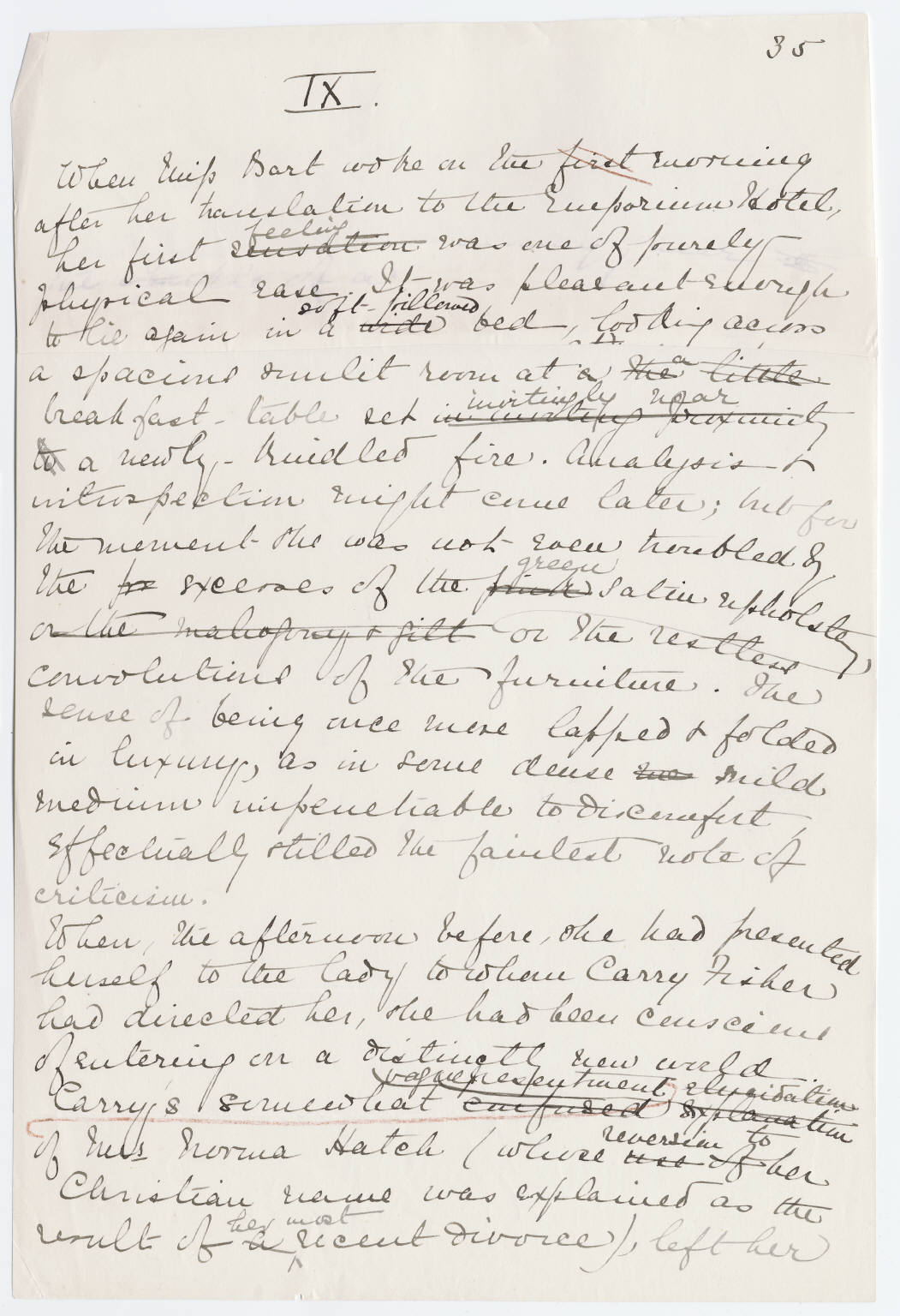

- The House of Mirth, 1905 (became a bestseller)

- The Fruit of the Tree, 1907

- The Reef, 1912

- The Custom of the Country, 1913 (received critical acclaim)

- Summer, 1917

- The Age of Innocence, 1920 (winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)

- The Glimpses of the Moon, 1922

- A Son at the Front, 1923

- The Mother's Recompense, 1925

- Twilight Sleep, 1927

- The Children, 1928

- Hudson River Bracketed, 1929

- The Gods Arrive, 1932

- The Buccaneers, 1938 (unfinished, published posthumously)

3.3.2. Novellas and Novelettes

Wharton's shorter fictional works often delve into concentrated psychological and social themes. Her notable novellas and novelettes include:

- The Touchstone, 1900

- Sanctuary, 1903

- Madame de Treymes, 1907

- Ethan Frome, 1911

- Bunner Sisters, 1916 (written in 1892)

- The Marne, 1918 (a war novella)

- Old New York, 1924 (a collection of four novellas: False Dawn, The Old Maid, The Spark, and New Year's Day)

- Fast and Loose: A Novelette, 1938 (written between 1876 and 1877, published posthumously)

3.3.3. Short Story Collections

Wharton's collections of short stories showcase her thematic range and mastery of the form, often exploring social nuances and human psychology. Her collections include:

- The Greater Inclination, 1899 (includes "Souls Belated")

- Crucial Instances, 1901

- The Descent of Man and Other Stories, 1904

- The Hermit and the Wild Woman and Other Stories, 1908

- Tales of Men and Ghosts, 1910

- Xingu and Other Stories, 1916 (includes "Xingu", "Coming Home", "Autres Temps ...", "Kerfol", "The Long Run", "The Triumph of Night", "The Choice", and "Bunner Sisters")

- Here and Beyond, 1926

- Certain People, 1930

- Human Nature, 1933

- The World Over, 1936

- Ghosts, 1937 (includes "All Souls'", "The Eyes", "Afterward", "The Lady's Maid's Bell", "Kerfol", "The Triumph of Night", "Miss Mary Pask", "Bewitched", "Mr. Jones", "Pomegranate Seed", and "A Bottle of Perrier")

- Roman Fever and Other Stories, 1964 (includes "Roman Fever", "Xingu", "The Other Two", "Souls Belated", "The Angel at the Grave", "The Last Asset", "After Holbein", and "Autres Temps")

- Madame de Treymes and Others: Four Novelettes, 1970 (includes "The Touchstone", "Sanctuary", "Madame de Treymes", and "Bunner Sisters")

- The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton, 1973 (includes "The Lady's Maid's Bell", "The Eyes", "Afterward", "Kerfol", "The Triumph of Night", "Miss Mary Pask", "Bewitched", "Mr Jones", "Pomegranate Seed", "The Looking Glass", and "All Souls")

- The Collected Stories of Edith Wharton, 1998

- The New York Stories of Edith Wharton, 2007

3.3.4. Poetry

Edith Wharton also contributed to poetry throughout her career, from early private publications to later collections. Her published poetry includes:

- Verses, 1878

- Artemis to Actaeon and Other Verse, 1909

- Twelve Poems, 1926

3.3.5. Non-fiction and Editorial Work

Beyond her fiction, Wharton produced a significant body of non-fiction, including works on design, travel, and literary criticism, and also engaged in editorial projects. Her non-fiction works include:

- The Decoration of Houses, 1897 (co-authored with Ogden Codman)

- Italian Villas and Their Gardens, 1904 (illustrated by Maxfield Parrish)

- Italian Backgrounds, 1905

- A Motor-Flight Through France, 1908

- The Cruise of the Vanadis, 1910 (her earliest known travel writing)

- Fighting France: From Dunkerque to Belfort, 1915 (a bestseller detailing her experiences at the front lines during World War I)

- French Ways and Their Meaning, 1919

- In Morocco, 1920 (a travelogue)

- The Writing of Fiction, 1925 (essays on the craft of writing)

- A Backward Glance, 1934 (her autobiography)

- Edith Wharton: The Uncollected Critical Writings, 1996 (edited by Frederick Wegener)

- Edith Wharton Abroad: Selected Travel Writings, 1888-1920, 1995 (edited by Sarah Bird Wright)

As an editor, Wharton notably compiled and edited The Book of the Homeless in 1916, a charity benefit volume that included contributions from many prominent contemporary European and American artists.

3.4. Plays

Edith Wharton also ventured into playwriting, with some of her works being staged or adapted. In 1901, she wrote a two-act play titled Man of Genius, which was rehearsed but ultimately never produced. Another play from 1901, The Shadow of a Doubt, was long thought to be lost until its rediscovery in 2017. It was adapted for BBC Radio 3 in 2018 and had its world stage premiere in 2023 in Canada at the Shaw Festival, directed by Peter Hinton-Davis. Wharton also collaborated with actress Marie Tempest on another play, though they only completed four acts before Tempest lost interest in costume plays. In 1902, Wharton translated the play Es Lebe das Leben ("The Joy of Living") by Hermann Sudermann. This translation was criticized for its title, given that the heroine swallows poison at the end, and had a short-lived run on Broadway, although it was a successful book.

4. Adaptations and Cultural Impact

Edith Wharton's literary works have been adapted into various media, extending her influence into film, television, radio, and theater, and her legacy continues to resonate in popular culture.

4.1. Film Adaptations

Many of Edith Wharton's novels and stories have been adapted into films, some of which are now considered lost.

- The House of Mirth (1918), a silent film directed by French film director Albert Capellani, starring Katherine Harris Barrymore as Lily Bart. This film is considered a lost film.

- The Glimpses Of The Moon (1923), a silent film adaptation directed by Allan Dwan for Paramount Studios, starring Bebe Daniels, David Powell, Nita Naldi, and Maurice Costello. This film is also considered a lost film.

- The Age of Innocence (1924), a silent film adaptation directed by Wesley Ruggles for Warner Brothers, starring Beverly Bayne and Elliott Dexter. This film is considered a lost film.

- The Marriage Playground (1929), a talking film adaptation of her 1928 novel The Children, directed by Lothar Mendes for Paramount Studios. It starred Fredric March, Mary Brian, and Kay Francis.

- The Age of Innocence (1934), a film adaptation directed by Philip Moeller for RKO Studios, starring Irene Dunne and John Boles.

- Strange Wives (1934), a film adaptation of her 1934 short story "Bread Upon the Waters", directed by Richard Thorpe for Universal. It starred Roger Pryor, June Clayworth, and Esther Ralston, and is considered a lost film.

- The Old Maid (1939), a film adaptation of her 1924 short novella, directed by Edmund Goulding and starring Bette Davis.

- A film version of her 1911 novel Ethan Frome starring Joan Crawford was proposed in 1944 but never came to fruition.

- The Children (1990), directed by Tony Palmer, starring Ben Kingsley and Kim Novak.

- Ethan Frome (1993), directed by John Madden, starring Liam Neeson and Patricia Arquette.

- The Age of Innocence (1993), directed by Martin Scorsese, starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Winona Ryder, and Michelle Pfeiffer. This adaptation is particularly well-known in Japan.

- The Reef (1999), directed by Robert Allan Ackerman.

- The House of Mirth (2000), directed by Terence Davies, starring Gillian Anderson as Lily Bart. This film was not released in Japan.

4.2. Television and Radio Adaptations

Edith Wharton's works have also been adapted for television and radio broadcasts.

- The Touchstone (1951), a live broadcast on CBS, marked the first television adaptation of a Wharton work.

- "Grey Reminder" (1951), an episode of NBC's Lights Out, was an adaptation of Wharton's story "The Pomegranate Seed", starring Beatrice Straight, John Newland, Helene Dumas, and Parker McCormick.

- Ethan Frome (1960), a CBS television adaptation directed by Alex Segal, starred Sterling Hayden as Ethan Frome, Julie Harris as Mattie Silver, and Clarice Blackburn as Zenobia Frome.

- Looking Back (1981), a US television production, was a loose adaptation drawing from two biographies of Edith Wharton: her own 1934 autobiography, A Backward Glance, and R.W.B. Lewis's 1975 biography, Edith Wharton.

- The House of Mirth (1981), a US television adaptation directed by Adrian Hall, starring William Atherton, Geraldine Chaplin, and Barbara Blossom.

- The stories "Afterward" and "Bewitched" were both featured in the 1983 Granada Television series Shades of Darkness.

- The Buccaneers (1995), a BBC mini-series, starred Carla Gugino and Greg Wise.

- The Buccaneers (2023), an Apple TV+ streaming series, stars Kristine Frøseth.

- The Age of Innocence had a Theatre Guild on the Air radio adaptation in 1947.

- "Edith Wharton's Journey" was a radio adaptation for the NPR series Radio Tales, based on the short story "A Journey" from Wharton's collection The Greater Inclination.

4.3. Theater Adaptations

Several of Edith Wharton's novels and stories have been adapted for the stage.

- The House of Mirth was adapted as a play in 1906 by Edith Wharton herself, in collaboration with Clyde Fitch.

- The Age of Innocence was adapted as a play in 1928, with Katharine Cornell playing the role of Ellen Olenska.

- The Old Maid was adapted for the stage by Zoë Akins in 1934. It was staged by Guthrie McClintic and starred Judith Anderson and Helen Menken. This play was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in May 1935. When published, the play's copyright included both Akins' and Wharton's names.

- Shadow of a Doubt had its world stage premiere in 2023, produced by the Shaw Festival and directed by Peter Hinton-Davis. The production featured design by Gillian Gallow (Set & Costume), Bonnie Beecher (Lighting), and HAUI (Live Video), and starred Katherine Gautier as Kate Derwent.

4.4. In Popular Culture

Edith Wharton and her works have been referenced in various forms of popular culture, demonstrating her lasting cultural footprint.

- Edith Wharton was honored on a U.S. postage stamp issued on September 5, 1980.

- In The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, Edith Wharton (portrayed by Clare Higgins) travels across North Africa with Indiana Jones in Chapter 16, titled Tales of Innocence.

- In the 2007 13th episode of the third season of the HBO television series Entourage, the character Vince is given a screenplay for Wharton's The Glimpses of the Moon for a film to be directed by Sam Mendes. In the same episode, agent Ari Gold lampoons period films based on Wharton's works, humorously stating that all her stories are "about a guy who likes a girl, but he can't have sex with her for five years, because those were the times!" Notably, Carla Gugino, who plays Amanda in the series, had previously starred as the protagonist in the 1995 BBC-PBS adaptation of Wharton's The Buccaneers.

- The television series Gilmore Girls makes various witty references to Wharton throughout its run. In season 1, episode 6, "Rory's Birthday Parties," Lorelai jokingly remarks, "Edith Wharton would be proud," referring to Emily's extravagant birthday party for Rory. This tradition of mentioning Wharton continues in Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life, with Lorelai quip to Emily in the first episode.

- In a 2009 episode of Gossip Girl titled "The Age of Dissonance," characters stage a production of a play version of The Age of Innocence, finding their personal lives mirroring the themes of the play.

- "Edith Wharton's Journey" is a radio adaptation, produced for the NPR series Radio Tales, based on the short story "A Journey" from Edith Wharton's collection The Greater Inclination.

- The American singer and songwriter Suzanne Vega paid homage to Edith Wharton in her song "Edith Wharton's Figurines," featured on her 2007 studio album Beauty & Crime.

- In Dawson's Creek, the character Pacey reads and takes a verbal quiz on Ethan Frome.

- The Magnetic Fields have a song that summarizes the plot of Ethan Frome.

5. Assessment and Legacy

Edith Wharton's enduring legacy is rooted in her profound contributions to American literature, her sharp social commentary, and her pioneering achievements as a female author. She is widely recognized for her satirical and refined style, which modernized naturalism in her depiction of upper-class society. Her novel The House of Mirth is celebrated for its incisive portrayal of social customs and their often tragic consequences, while The Age of Innocence earned her the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, solidifying her place as a literary giant and the first woman to receive the award. The Modern Library recognized the significance of these works by ranking The Age of Innocence 58th and The House of Mirth 69th among the 100 best novels of the 20th century. Her short story "Roman Fever" is particularly acclaimed as a masterpiece of the genre.

Wharton's critical reception has evolved over time, but her importance as a chronicler of the Gilded Age and a master of psychological realism remains undiminished. Her ability to dissect the constraints of society, the complexities of human relationships, and the often-repressed desires of her characters set her apart. Beyond her literary achievements, her humanitarian efforts during World War I earned her the prestigious Legion of Honour from France, showcasing her commitment to social welfare. Her induction into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1996 further cemented her status as a figure of significant historical and cultural impact. Wharton's meticulous prose, thematic depth, and unflinching examination of societal norms continue to be studied and admired, ensuring her lasting influence on the American literary tradition.