1. Early Life and Amateur Career

Eddy Merckx's journey to becoming a cycling icon began in his early childhood, marked by an energetic nature and a natural inclination towards sports before he found his true calling in cycling.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Édouard Louis Joseph Merckx was born on 17 June 1945 in Meensel-Kiezegem, Brabant, Belgium, to Jules Merckx and Jenny Pittomvils. He was the firstborn of the family. In September 1946, his family relocated to Woluwe-Saint-Pierre (Sint-Pieters-Woluwe) in Brussels, Belgium, to take over a grocery store. In May 1948, his mother gave birth to twins, Michel and Micheline.

1.2. Childhood and Early Sports

As a child, Eddy was hyperactive and spent much of his time playing outdoors. He was highly competitive and participated in various sports, including basketball, football, table tennis, and boxing, even winning some local boxing tournaments. He also played lawn tennis for his local junior team. However, Merckx claimed that he knew he wanted to be a cyclist from the age of four, recalling his first memory as a bicycle crash at the same age. He began riding a bike at three or four and cycled to school daily starting at age eight. Merckx would often imitate his cycling idol, Stan Ockers, when riding bikes with his friends.

1.3. Amateur Cycling Career

Merckx bought his first racing license in the summer of 1961 and competed in his first official race a month after turning sixteen, finishing sixth. He participated in twelve more races before securing his first victory in Petit-Enghien on 1 October 1961. During the following winter, he trained at a local velodrome with former racer Félicien Vervaecke. Merckx achieved his second victory on 11 March 1962 in a kermis race. He competed in 55 races in 1962, and as he dedicated more time to cycling, his school grades declined. After winning the Belgian amateur road race title, Merckx declined an offer to postpone his exams and dropped out of school, finishing the season with 23 victories.

In 1964, Merckx won the amateur road race at the 1964 UCI Road World Championships in Sallanches, France. The following month, he competed in the individual road race at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, finishing twelfth. He was selected as a Belgian road cyclist for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and came to Japan. His official time was 4 hours 39 minutes 51 seconds, which was the same time as the winning record due to the official records being in seconds during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics era. More precisely, it was 4 hours 39 minutes 51.74 seconds, the same time as the third-place finisher. He was placed 12th by photo finish. This race was notably close, with many riders up to around 30th place having the same time down to hundredths of a second. There were rumors that he might have won if he hadn't crashed in the latter half of the race, but the crash itself remains unconfirmed. Merckx remained an amateur until April 1965, concluding his amateur career with a remarkable eighty victories.

2. Professional Career

Eddy Merckx's professional career, spanning from 1965 to 1978, is a testament to his unparalleled talent and relentless drive, marked by numerous victories across all major cycling disciplines.

2.1. 1965-1967: Early Professional Years (Solo-Superia and Peugeot)

Merckx turned professional on 29 April 1965, signing with Rik Van Looy's Belgian team, Solo-Superia. He secured his first professional victory in Vilvoorde, beating Emile Daems. On 1 August, he finished second in the Belgian national championships, qualifying him for the UCI Road World Championships. At this event, Raphaël Géminiani, manager of the Bic cycling team, offered Merckx 2.50 K FRF a month to join his team for the next season. Merckx initially agreed but the contract was invalid as he was a minor.

After finishing 29th in the World Championships road race, Merckx returned to Belgium and discussed his plans with his manager, Jean Van Buggenhout. Van Buggenhout helped arrange a move to the French-based Peugeot-BP-Michelin team for 20.00 K FRF a month. Merckx chose to leave Solo-Superia due to the way he was treated by his teammates, particularly Van Looy, who mocked his habits and called him names. Merckx later stated that he learned nothing during his time with Van Looy's team. While with Solo-Superia, he won nine of the nearly 70 races he entered.

In March 1966, Merckx entered his first major professional stage race, the Paris-Nice. He held the race lead for one stage before losing it to Jacques Anquetil and ultimately finishing fourth overall. The Milan-San Remo, his first participation in one of cycling's Monuments, was his next event. He stayed with the main field as the race approached the final climb of the Poggio. He attacked on the climb, reducing the field to eleven riders. Following his manager's advice to delay his full sprint, Merckx out-sprinted three other riders to win the race. In the following weeks, he raced the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix; he crashed in the former and suffered a punctured tire in the latter. At the 1966 UCI Road World Championships, he finished twelfth in the road race after suffering a cramp in the closing kilometers. He concluded the 1966 season with 20 victories, including his first stage race win at the Tour of Morbihan. In March 1966, Merckx, accompanied by fellow countryman Herman Van Springel (who, though from another team, would later be touted by the media as Merckx's "lifelong rival" but was actually a friend), first visited the Masi workshop in Milan, Italy. Van Springel, who was two years younger and in his first full professional season with no significant achievements, thought highly of Merckx. He reportedly told Alberto Masi, the craftsman at the workshop, "This rookie (Merckx) will probably finish in the top 3 in Milan-San Remo (held a few days later)." With the frame made at that time, Merckx won his first major professional title, Milan-San Remo. Van Springel also achieved his personal best, finishing 3rd.

Merckx opened the 1967 campaign with two stage victories at the Giro di Sardegna. He then entered Paris-Nice, winning the second stage and taking the race lead. Two stages later, his teammate, Tom Simpson, attacked with several other riders, gaining nearly 20 minutes on Merckx. Two days later, Merckx attacked on a climb 43 mile (70 km) into the stage, establishing a strong lead, but obeyed orders to wait for the chasing Simpson. Merckx won the stage, while Simpson secured the overall victory.

On 18 March, Merckx started the Milan-San Remo as a 120-1 favorite. He attacked on the Capo Berta and again on the Poggio, leaving only Gianni Motta with him. The two slowed, and two more riders joined them. Merckx won the four-man sprint. His next victory came in La Flèche Wallonne after he missed an early break, caught up, and attacked to win. On 20 May, he started the Giro d'Italia, his first Grand Tour. He won the twelfth and fourteenth stages, finishing ninth in the general classification.

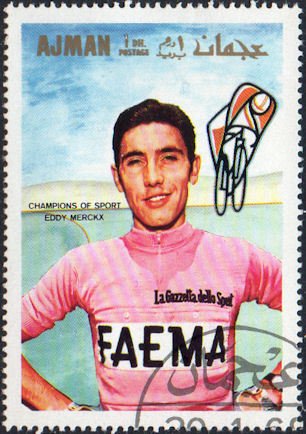

He signed with Faema on 2 September for a ten-year contract worth 400.00 K BEF. He chose to switch teams to gain complete control over his racing environment and avoid personal expenses for equipment like wheels and tires. The next day, Merckx started the men's road race at the 1967 UCI Road World Championships in Heerlen, Netherlands. The course involved ten laps of a circuit. Motta attacked on the first lap, joined by Merckx and five others. The group thinned to five by the finish, where Merckx out-sprinted Jan Janssen for first place. This made him the third rider to win both the amateur and professional world road race titles, earning him the rainbow jersey.

2.2. 1968-1970: Faema Era

Merckx's first victory with Faema came in a stage win at the Giro di Sardegna. At Paris-Nice, he withdrew due to a knee injury. He failed to win his third consecutive Milan-San Remo and missed out at the Tour of Flanders. His next victory was at Paris-Roubaix, where he defeated Herman Van Springel in a race marred by poor weather and multiple punctures.

At his team's request, Merckx raced the Giro d'Italia instead of the Tour de France. He won the second stage with a 0.6 mile (1 km) attack. The twelfth stage was plagued by rain and featured the climbs of Tre Cime di Lavaredo. By the penultimate climb, a six-man group had a nine-minute lead. Merckx attacked, gained a significant lead, but stopped to change his wheel due to team orders. He then caught and passed the leaders, winning the stage and taking the overall lead. Merckx went on to win the race, along with the points classification and mountains classification. In the Volta a Catalunya, Merckx took the lead from Felice Gimondi in the time trial stage and won the event. He finished the 1968 season with 32 wins from 129 races.

Merckx began the 1969 season with victories at the Vuelta a Levante and the Paris-Nice overall, winning stages in both. On 30 March 1969, he secured his first major victory of the year at the Tour of Flanders. On a rainy, windy day, he attacked on the Oude Kwaremont but a puncture nullified his gains. He then attacked on the Kapelmuur, followed by a few riders. As the wind shifted to a headwind with 43 mile (70 km) remaining, Merckx increased his pace and rode solo to victory. In the seventeen days after the Tour of Flanders, Merckx won nine times. He won Milan-San Remo by descending the Poggio at high speed. In mid-April, he won Liège-Bastogne-Liège with an attack 43 mile (70 km) from the finish.

He started the Giro d'Italia on 16 May, intending to ride less aggressively to save energy for the Tour de France. Merckx had won four stages and held the race lead going into the sixteenth day. However, before the start of the stage, race director Vincenzo Torriani, accompanied by a television camera and two writers, informed Merckx in his hotel room that he had failed a doping control and was disqualified from the race, receiving a one-month suspension. Merckx had previously tested negative eight times during the race. He argued that his samples had been mishandled. The majority of the international press believed in his innocence, finding it illogical that he would use banned substances on an easy stage when a doping test was certain for the leader. Several conspiracy theories emerged, including that the urine sample was not Merckx's or that he had been given a water bottle containing the stimulant, ostensibly to give Italian rider Felice Gimondi a better chance at victory. On 14 June, the cycling governing body, the FICP, overturned the suspension, clearing him due to "benefit of the doubt."

Before starting the Tour de France, Merckx spent much time resting and training, racing only five times. He won the Tour's sixth stage by attacking before the final major climb, the Ballon d'Alsace, and outlasting his initial followers. During the seventeenth stage, Merckx was at the front with several general classification contenders on the Col du Tourmalet. He attacked in a large gear, crossing the summit with a 45-second lead. Despite orders to wait, Merckx increased his efforts, riding over the Col du Soulor and Col d'Aubisque, extending his lead to eight minutes. With nearly 31 mile (50 km) to go, Merckx suffered hypoglycemia and rode the rest of the stage in severe pain. After finishing, he famously told journalists, "I hope I have done enough now for you to consider me a worthy winner." Merckx finished the Tour with six stage victories, winning the general, points, mountains, and combination classifications, and the award for most aggressive rider.

His next major race was the two-day Paris-Luxembourg. Merckx was 54 seconds down going into the second day and attacked 5.0 mile (8 km) from the finish on the slopes of Bereldange. He rode solo to catch Jacques Anquetil, dropping him with a kilometer remaining, and gained enough time on race leader Gimondi to win the race.

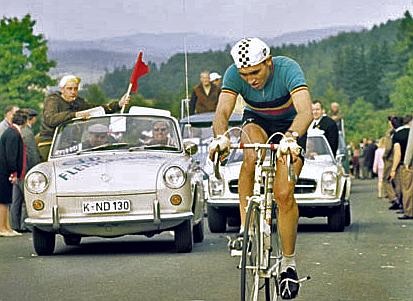

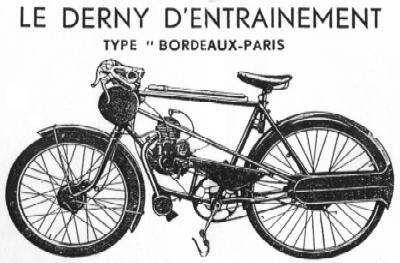

On 9 September, Merckx participated in a three-round omnium event at the concrete velodrome in Blois, where riders were paced by a derny. Fernand Wambst was Merckx's pacer. After winning the first intermediate sprint, Wambst slowed to move to the back, despite Merckx's fear of an accident. Wambst wanted to pass everyone for a show. As they increased pace and passed other contestants, the leading derny lost control and crashed into the wall. Wambst tried to avoid it by going below, but the leader's derny came back down, colliding with Wambst, and Merckx's pedal caught one of the dernies. Both riders landed head-first onto the track. Wambst died of a fractured skull during transport to a hospital. Merckx remained unconscious for 45 minutes, waking in the operating room. He sustained a concussion, whiplash, trapped nerves in his back, a displaced pelvis, and several cuts and bruises. He stayed in the hospital for a week, then spent six weeks in bed before racing again in October. Merckx later stated that he "was never the same again" after the crash, constantly adjusting his seat height during races to ease the pain.

Merckx entered the 1970 campaign with mild tendonitis in his knee. His first major victory was in Paris-Nice, where he won the general classification and three stages. On 1 April, Merckx won the Gent-Wevelgem, followed by the Tour of Belgium (braving a snowy stage and winning the final time trial) and Paris-Roubaix. In Paris-Roubaix, battling a cold in heavy rain, he attacked 19 mile (31 km) from the finish, winning by five minutes and twenty-one seconds, the largest margin of victory in the race's history. The next weekend, Merckx attempted to race for teammate Joseph Bruyère in La Flèche Wallonne, but Bruyère couldn't keep pace, leaving Merckx to take the victory.

After the previous year's Giro d'Italia scandal, Merckx was reluctant to return in 1970. His entry was conditional on all doping controls being sent to a lab in Rome, not tested at the finish. He started the race, winning the second stage, but four days later showed knee weakness, being dropped twice in the mountains. The next day, Merckx attacked on the final climb into Brentonico to win the stage and take the lead. He won the stage nine individual time trial by almost two minutes, significantly expanding his lead. He did not win another stage but slightly increased his lead before the race's conclusion.

Before the Tour de France, Merckx won the men's road race at the Belgian National Road Race Championships. He won the Tour's opening prologue, taking the first yellow jersey. He lost the lead after the second stage but regained it by winning the sixth stage after forming a breakaway with Lucien Van Impe. After expanding his lead in the stage nine individual time trial, Merckx won the race's first true mountain stage, stage 10, extending his lead to five minutes. Merckx won three of the next five stages, including a summit finish to Mont Ventoux, where he needed oxygen upon finishing. He won two more stages, both individual time trials, and won the Tour by over twelve minutes. He finished with eight stage victories, winning the mountains and combination classifications. These eight stage wins equaled the previous record for stage wins in a single Tour de France. Merckx also became the third rider to achieve the feat of winning the Giro and Tour in the same calendar year.

2.3. 1971-1976: Molteni Era

Faema disbanded at the end of the 1970 season, leading Merckx and several teammates to join the Italian team, Molteni. His first major victory with Molteni came in the Giro di Sardegna, which he secured by attacking solo through the rain to win the final stage. He followed this with his third consecutive Paris-Nice victory, a race he led from start to finish. In the Milan-San Remo, Merckx worked with his teammates in a seven-man breakaway to set up a final attack on the Poggio. His attack succeeded, and he won his fourth edition of the race. Six days later, he won the Omloop Het Volk.

After winning the Tour of Belgium again, Merckx entered the major spring classics. During the Tour of Flanders, his rivals actively worked against him to prevent his victory. A week later, he suffered five flat tires during Paris-Roubaix. The Liège-Bastogne-Liège was held in cold and rainy conditions. After attacking 56 mile (90 km) from the finish, Merckx caught and passed the leaders. He rode solo until about 1.9 mile (3 km) to go when Georges Pintens caught him. Merckx and Pintens rode to the finish together, where Merckx won the two-man sprint. Instead of racing the Giro d'Italia, Merckx chose to enter two shorter stage races in France, the Grand Prix du Midi Libre and the Critérium du Dauphiné, winning both.

The Tour de France began with a team time trial that Merckx's team won, giving him the lead. The next day's racing was split into three parts. Merckx lost the lead after stage 1b but regained it after stage 1c due to a time bonus from an intermediate sprint. During the second stage, a major break formed with Merckx and other contenders over 62 mile (100 km) from the finish. The group finished nine minutes ahead of the peloton, with Merckx winning the sprint against Roger De Vlaeminck. After a week of racing, Merckx held about a minute's lead over his main rivals. The eighth stage featured a mountain top finish to Puy-de-Dôme. Bernard Thévenet attacked on the lower slopes, and Merckx could not counter. Joop Zoetemelk and Luis Ocaña went with Thévenet, gaining fifteen seconds on Merckx.

On the descent of the Col du Cucheron during the ninth leg, Merckx's tire punctured, prompting Ocaña to attack with Zoetemelk, Thévenet, and Gösta Pettersson. This group finished a minute and a half ahead of Merckx, giving Zoetemelk the lead. The following day, Merckx lost eight minutes to Ocaña due to stomach pains and indigestion. At the start of the eleventh stage, Merckx, three teammates, and a few others formed a breakaway. Merckx's group finished two minutes ahead of the peloton, led by Ocaña's Bic team. After winning the ensuing time trial, Merckx gained eleven more seconds on Ocaña. The race entered the Pyrenees, with the first stage into Luchon plagued by heavy thunderstorms that severely limited visibility. On the descent of the Col de Menté, Merckx crashed on a left bend. Ocaña, who was trailing, crashed into the same bend, and Zoetemelk collided with him. Merckx fell again on the descent and took the race lead as Ocaña was forced to retire due to injuries. Merckx declined to wear the yellow jersey the following day out of respect for Ocaña. He won two more stages and the general, points, and combination classifications when the race finished in Paris.

Seven weeks following the Tour, Merckx entered the men's road race at the UCI Road World Championships that were held in Mendrisio, Switzerland. The route for the day was rather hilly and consisted of several circuits. Merckx was a part of a five-man breakaway as the race reached five laps to go. After attacking on the second to last stage, Merckx and Gimondi reached the finish, where Merckx won the race by four bike lengths. This earned him his second rainbow jersey. He closed out the 1971 calendar with his first victory in the Giro di Lombardia. This victory meant that Merckx had won all of cycling's Monuments. Merckx made the winning move when he attacked on the descent of the Intelvi Pass. During the off-season, Merckx had his displaced pelvis tended to by a doctor.

Due to his non-participation in track racing over the winter, Merckx entered the 1972 campaign in poorer form than in previous years. In the Paris-Nice, Merckx broke a vertebra in a crash that occurred as the peloton was in the midst of a bunch sprint. Against the advice of a physician, he started the next day being barely able to ride out of the saddle, leading Ocaña to attack him several times throughout the stage. In the race's fifth leg, Merckx sprinted away from Ocaña with 492 ft (150 m) to go to win the day. Merckx lost the race lead in the final stage to Raymond Poulidor and finished in second place overall. Two days removed from Paris-Nice, Merckx was victorious for the fifth time at the Milan-San Remo after he established a gap on the descent of the Poggio.

In Paris-Roubaix, he crashed again, further aggravating the injury he sustained from Paris-Nice. He won Liège-Bastogne-Liège by making a solo move 29 mile (46 km) from the finish. Three days later, in La Flèche Wallonne, Merckx was a part of a six-man leading group as the race neared its conclusion. Merckx won the uphill sprint to the finish despite his derailleur shifting him to the wrong gear, forcing him to ride in a larger gear than anticipated. He became the third rider to win La Flèche Wallonne and Liège-Bastogne-Liège in the same weekend. Despite a monetary offer from race organizers for Merckx to participate in the Vuelta a España, he chose to take part in the Giro d'Italia.

Merckx lost over two and a half minutes to Spanish climber José Manuel Fuente after the Giro's fourth stage that contained a summit finish to Blockhaus. In the seventh stage, Fuente had attacked on the first climb of the day, the Valico di Monte Scuro. However, Fuente cracked near the top of the climb, allowing for Merckx and Pettersson to catch and pass him. Merckx gained over four minutes on Fuente and became the new race leader. He expanded his lead by two minutes through the stage 12a and 12b time trials, winning the former. Fuente got Merckx on his own as the two climbed together during the fourteenth stage. He and teammate Francisco Galdós attacked, leaving Merckx behind. Merckx eventually reconnected with the two on the final climb of the stage. He proceeded to attack and went on to win the stage by forty-seven seconds. He lost two minutes to Fuente due to stomach trouble during the seventeenth leg that finished atop the Stelvio Pass, but went on to win one more stage en route to his third victory at the Giro d'Italia.

Merckx entered the Tour de France in July where a battle between him and Ocaña was expected by many. He took the opening prologue and expanded his advantage over all the other general classification contenders, except Ocaña, by at least three minutes. Going into the Pyrenees, Merckx led Ocaña by fifty-one seconds. The general classification favorites were riding together as the race hit the Col d'Aubisque in the seventh leg. Ocaña punctured on the climb, allowing for the other riders to attack. Ocaña chased after the group but crashed into a wall on the descent and went on to lose almost two minutes to Merckx. Merckx was criticized for attacking while Ocaña had a flat, but Merckx responded that the year before Ocaña had done the same thing while the race was in the Alps. Merckx won the following stage, regaining the lead which he had lost after the fourth leg. During the next two major mountain stages, one to Mont Ventoux and the other to Orcières, he merely followed Ocaña's wheel. He won three more stages before crossing the finish line in Paris as the race's winner, thus completing his second Giro-Tour double in the process.

After initially planning to attempt to break the hour record in August, Merckx decided to make the attempt in October after taking a ten-day hiatus from criterium racing to heal and prepare. The attempt took place on 25 October in Mexico City, Mexico at the outdoor track Agustin Melgar. Mexico was chosen due to the higher altitude as this led to less air resistance. He arrived in Mexico on the 21st to prepare for his attempt, but two days were lost due to rain. His attempt started at 8:46 am local time and saw him finish the first ten kilometers twenty-eight seconds faster than the record pace. However, Merckx started off too fast and began to fade as the attempt wore on. He eventually was able to recover and posted a distance of 31 mile (49.431 km), breaking the world record. After finishing he was carried off and was quoted saying the pain was "very, very, very significant." The Colnago-designed bike used for this attempt weighed just 13 lb (5.75 kg) (compared to the average of 22 lb (10 kg) for road bikes at the time), featuring titanium parts and extensive lightweight modifications, including drilling holes in gears and handlebars. This bike is displayed at the Eddy Merckx metro station in Brussels. When Merckx set the Hour Record (49.431 km) in 1973, it was said that no one could break it. This record stood for many years until it was broken by Italian Francesco Moser in 1984 with a distance of 32 mile (50.808 km), but it was not recognized by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) because Moser used a bicycle made of lightweight materials, with aero bars and disc wheels, specially designed for aerodynamics. Merckx's record was later broken by British Chris Boardman on 27 October 2000, with a distance of 31 mile (49.441 km), using a standard racing bicycle. The record stood for a total of 28 years. Due to a UCI rule change in 2000, the Hour Record was mandated to be set using "standard track racing bicycles," nullifying all those records set with specialized bikes. In 2014, the rules were revised again, allowing the use of aero helmets, disc wheels, and DH bars, as used in track individual and team pursuits, completely changing the conditions. However, the highest record under the 2000 rules, set by Ondřej Sosenka in 2005, 32 years after Merckx's record, was 31 mile (49.7 km), only 0.2 mile (0.3 km) more than Merckx's record. Considering the significant advancements in equipment, such as aerodynamics research and carbon materials, for track racing bicycles, it is evident how overwhelming Merckx's record was.

An illness prevented Merckx from taking part in the Milan-San Remo at the start of the 1973 calendar. During a span of nineteen days, Merckx won four classics including Omloop Het Volk, Liège-Bastogne-Liège, and Paris-Roubaix. He decided to race the Vuelta a España and the Giro d'Italia, instead of racing the Tour de France. He won the opening prologue of the Vuelta to take an early lead. Despite Ocaña's best efforts, Merckx won a total of six stages on his way to his only Vuelta a España title. In addition to the general classification, Merckx won the race's points classification and combination classifications.

Four days after the conclusion of the Vuelta, Merckx lined up to start the Giro d'Italia. He won the opening two-man time trial with Roger Swerts and the next day's leg as well. Merckx's primary competitor, Fuente, lost a significant amount of time during the second stage. He won the eighth stage which featured a summit finish to Monte Carpegna despite Fuente attacking several times on the ascent. Fuente tried attacking throughout the rest of the race, but was only able to make time gains on the race's penultimate stage. Merckx won the race after leading from start to finish, a feat only previously accomplished by Alfredo Binda and Costante Girardengo. He also became the first rider to win the Giro and Vuelta in the same calendar year.

The UCI Road World Championships were held in Barcelona, Spain in 1973 and contested on the Montjuich circuit. During the road race, Merckx attacked with around 62 mile (100 km) left. His move was marked by Freddy Maertens, Gimondi, and Ocaña. Merckx attacked on the final lap, but was reeled in by the three riders. It came down to a sprint between the four, of which Merckx came in last and Gimondi in first. Following the road race, Merckx won his first Paris-Brussels and Grand Prix des Nations. He won both legs of À travers Lausanne, as well as the Giro di Lombardia, but a doping positive disqualified him. He closed the season with over fifty victories to his credit.

The 1974 season saw Merckx fail to win a spring classic for the first time in his career, in part due to him suffering from various illnesses during the early months. Pneumonia forced him to quit racing for a month and forced him to enter the Giro d'Italia in poor form. He lost time early in the race to Fuente, who took the race's first mountainous stage. Merckx gained time on Fuente in the race's only time trial. Merckx attacked from 124 mile (200 km) out two days later in a stage that was plagued by horrendous weather. Fuente lost ten minutes to Merckx, who became the race leader. The twentieth stage had a summit finish to Tre Cime di Lavaredo. Fuente and Gianbattista Baronchelli attacked on the climb, while Merckx was unable to match their accelerations. He finished the stage only to see his lead shrink to twelve seconds over Baronchelli. He held on to that lead until the race's conclusion, winning his fifth Giro d'Italia.

Three days following his victory at the Giro, Merckx started the Tour de Suisse. He won the race's prologue and rode conservatively for the rest of the race. He took the final leg, an individual time trial, to seal his overall victory. After finishing the race, Merckx had a sebaceous cyst removed on 22 June. Five days following the surgery, he was scheduled to begin the Tour de France. The wound was still slightly open when he began the Grand Tour and it bled throughout the race.

At the Tour, Merckx won the race's prologue, giving him the first race leader's yellow jersey (maillot jauneFrench), which he lost the next day to teammate Joseph Bruyère. He won the seventh stage of the race, and regained the lead, through attacking in the closing kilometers and holding off the chasing peloton. He put five minutes into Poulidor, his main rival, after dropping him on the Col du Galibier. The next day, on the slopes of Mont Ventoux, Merckx rode to limit his losses after suffering several attacks from other general classification riders, including Poulidor, Vicente López Carril and Gonzalo Aja. He expanded his lead through several stage victories afterward, including one where he attacked with 6.2 mile (10 km) to go in a flat stage and held off the peloton to reach the finish in Orléans almost a minute and a half before the chasing group. Merckx finished the Tour with eight stage wins and his fifth Tour de France victory, equaling the record of Anquetil.

Going into the men's road race at the UCI Road World Championships, Merckx anchored a squad that included Van Springel, Maertens, and De Vlaeminck. The route featured twenty-one laps of a circuit that contained two climbs. Merckx and Poulidor attacked with around 4.3 mile (7 km) to go, after catching the leading breakaway. The two rode to the finish together where Merckx won the sprint to the line, establishing a two-second gap between himself and Poulidor. By winning the road race, Merckx became the first rider to win the Triple Crown of Cycling, which consists of winning the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia, and men's road race at the World Championships in one calendar year. It was also his third world title, becoming the third rider to ever be world champion three times, after Binda and Rik Van Steenbergen.

With victories at Milan-San Remo and Amstel Gold Race, Merckx opened the 1975 season in good form, also winning the Setmana Catalana de Ciclisme. In the Catalan Week, Merckx lost his super domestique Bruyère, who had helped Merckx to victory in years past many times, to a broken leg. Two days following the Catalan Week, Merckx participated in the Tour of Flanders. He launched an attack with 50 mile (80 km) to go, with only Frans Verbeeck being able to match his acceleration. Verbeeck was dropped as the race reached 3.1 mile (5 km) remaining, allowing Merckx to take his third Tour of Flanders victory. In Paris-Roubaix, Merckx suffered a flat tire with around 50 mile (80 km) left when a part of a leading group of four. After chasing for 1.9 mile (3 km), he caught the three other riders and the group rode into the finish together; De Vlaeminck won the day. Merckx won his fifth Liège-Bastogne-Liège by attacking several times in the closing portions of the race.

Merckx's attitude while racing had changed: riders expected him to chase down attacks, which angered him. Notably, in the Tour de Romandie he was riding with race leader Zoetemelk as an attack occurred. Merckx refused to chase the break down, and the two lost fourteen minutes. Merckx contracted a cold and, later, tonsilitis while racing in the spring campaign. This caused him to be in poor form, forcing him to not participate in the Giro d'Italia. He then rode in the Dauphiné Libéré and was not on par with Thevenet, who won the race. At the Tour de Suisse, De Vlaeminck won the race as a whole, while Merckx finished second.

He placed second in the Tour de France's prologue. The following morning's split stage saw Merckx put time on Thevenet by attacking with Francesco Moser, Van Impe, and Zoetemelk. In day's second leg, Merckx gained time on Zoetemelk. He won the stage six individual time trial and gaining more time on Thevenet and Zoetemelk. He won the next time trial into Auch as well. During the race's eleventh stage, Merckx sent his team to set the pace early on in the stage. Reaching the final climb of the day, Merckx was on his own as his team had been used to set the pace throughout the day. On the day's final climb to Pla d'Adet, he matched an acceleration by Zoetemelk. Thevenet then launched an attack, to which Merckx could not follow and saw him lose over two minutes. After the stage Merckx switched decided to mark Thevenet for the rest of the race and make an attack on the Puy-de-Dôme.

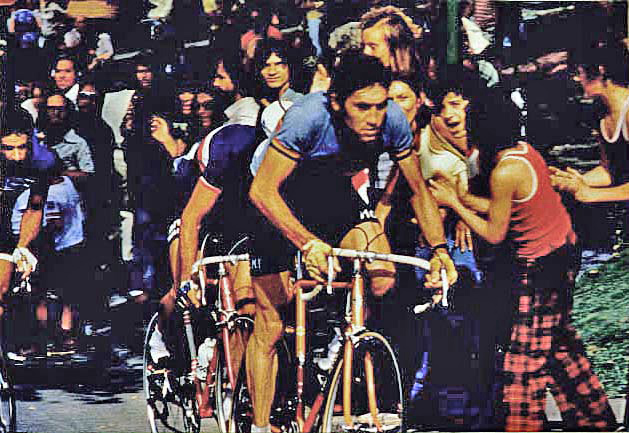

While climbing the Puy-de-Dôme, Thevenet and Van Impe attacked. Merckx followed at his own pace and kept the two riders within 328 ft (100 m). With about 492 ft (150 m) remaining, Merckx was prepared to sprint to the line, but was punched in the back by a spectator, Nello Breton. He crossed the line thirty-four seconds behind Thevenet and proceeded to vomit after catching his breath. The punch left him with a large bruise. During the rest day he was found to have an inflamed liver for which he was prescribed blood thinners.

The stage following the rest day featured five climbs, Merckx felt a pain on the third climb in the area of the punch and had a teammate get him an analgesic. Thevenet attacked several times on the climb of the Col des Champs, all of which Merckx countered. Merckx retaliated by speeding away on the descent. On the start of the next climb, Merckx had his Molteni teammates set the pace and he distanced himself from his competitors before the start of the final climb. However, as Merckx began the final climb he cracked. Thevenet caught and passed him with 2.5 mile (4 km) left. Gimondi, Van Impe, and Zoetemelk passed Merckx, who finished fifth and one minute and twenty-six seconds down. The following day, Merckx caught up with the leading breakaway and wanted to push ahead, but the riders chose not to participate in the pace making, leading Merckx to sit up and get caught. He lost two more minutes to Thevenet, who attacked on the Col d'Izoard. He crashed in the next leg, breaking a cheekbone, and gained some time on Thevenet before the finish in Paris. He finished in second place, the first time he had lost a Tour in his six starts. The excessive effort in the 1975 Tour de France shortened his career, and he later admitted that he "could have ridden a little longer" if not for that incident. Some speculated that if there had been no interference, he could have achieved 8 consecutive victories (or more) from 1968-1975.

He opened his 1976 season with his record seventh victory in Milan-San Remo. He followed with a victory in the Catalan Week, but suffered a crash in the final stage when a spectator's bag caught his handlebars, injuring his elbow. This injury plagued his performance throughout the spring classic season. He entered the Giro d'Italia but failed to win a stage for the first time in his career. He finished the race in eighth overall while battling a saddle boil throughout the race. Following the Giro's conclusion Merckx announced that he and his team Molteni would not take part in the Tour de France. He took part in the men's road race at the UCI Road World Championships and finished in fifth position. He ended his season in October after racing for most of August. He failed to win the Super Prestige Pernod International, a competition where riders were awarded points for their placements in certain professional races, for the first time since 1968. In the first two months of his off-season, Merckx spent the majority of his time lying down. Molteni ended their sponsorship at the end of the season.

2.4. 1977-1978: Final Seasons (Fiat France and C&A)

Fiat France became the new sponsor for Merckx's team and Raphaël Géminiani the new manager. He got his season's first victories in the Grand Prix d'Aix and Tour Méditerranéen. Merckx agreed to ride a light spring season in order to save himself for a chance at a sixth Tour victory. He took one stage at the Paris-Nice but had to withdraw from the race's final stage due to sinusitis. In the spring classics, Merckx did not win any races, with his best finish being a sixth place in the Liège-Bastogne-Liège. Before the Tour, Merckx raced both the Dauphiné Libéré and Tour de Suisse, winning one stage of the latter.

He admitted his poor form and anxiety about aggravating previous injuries going into the Tour de France. He held on to second place overall for two weeks. As the race entered the Alps, Merckx began to lose more time; he lost thirteen minutes on the stage to Alpe d'Huez alone. On the stage into Saint-Étienne, Merckx attacked and gained enough time to move into sixth overall; he finished the Tour in the same position. In the time following the Tour, Merckx raced 22 races in a span of forty days before coming in thirty-third at the UCI Road World Championships men's road race. Merckx earned his final victory on the road on 17 September in a kermis race. In late December, Fiat France chose to end their sponsorship of Merckx in favor of building a more French centered squad.

In January 1978, the department store C&A announced that they would sponsor a new team for Merckx after their owner met Merckx at a football game. His plan for the season was to race one last Tour de France and then ride several smaller races for appearances. He raced a total of five races in the 1978 calendar. His last victory was in a track event, an omnium in Zürich, on 10 February 1978 with Patrick Sercu. His first road race came in the Grand Prix de Montauroux on 19 February. Merckx came to the front of the race and put in a large effort before swinging off and quitting the race. His best finish came in the Tour de Haut, where he managed fifth. He dropped out of Omloop Het Volk due to colitis and completed his final race on 19 March, a kermis in Kemzeke. Following the race, Merckx went on a vacation to go skiing. He returned from travel to train more, but by this point the team sponsor knew he was going to quit. Merckx announced his retirement from the sport on 18 May. He stated that the doctors advised him against racing.

3. Major Achievements and Records

Eddy Merckx's career is distinguished by an extraordinary collection of victories and records that underscore his dominance across all facets of professional cycling.

3.1. Grand Tour Victories

Merckx holds the record for the most Grand Tour wins with 11 victories, including five each in the Tour de France and Giro d'Italia, and one Vuelta a España title. He also holds the record for most stage wins across all three Grand Tours with 64. He completed the Giro-Tour double three times, more than any other rider.

3.1.1. Tour de France Records

Merckx shares the record for most Tour de France wins with five victories (1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1974), a feat shared with Jacques Anquetil, Bernard Hinault, and Miguel Induráin. He also shares the record for most stage wins in a single Tour de France with 8 victories (in 1970), a record he shares with Charles Pélissier and Freddy Maertens. His total of 34 Tour de France stage wins was the highest record for 38 years, from 1975 to 2023. He holds the record for the most days spent in the yellow jersey with 96 days. Merckx was the first rider to win all three specialties (mountain, sprint, and individual time trial) in a single Tour de France in 1974. He is also the only rider to win the general, points, and mountains classifications in the Tour de France, achieving this in 1969. He holds the record for most combativity awards in the Tour de France, with four (1969, 1970, 1974, 1975).

3.1.2. Giro d'Italia Records

Merckx shares the record for most Giro d'Italia wins with five victories (1968, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1974), a record shared with Alfredo Binda and Fausto Coppi. He holds the record for most days in the pink jersey with 78 days. He is the only rider to win the general, points, and mountains classifications in the Giro d'Italia, which he did in 1968. For his career successes in the Giro d'Italia, Merckx became the first rider inducted into the race's Hall of Fame in 2012.

3.2. Monument Victories

Merckx is one of only three riders to have won all five 'Monuments of Cycling' (Milan-San Remo, Tour of Flanders, Paris-Roubaix, Liège-Bastogne-Liège, and the Giro di Lombardia), the others being Rik Van Looy and Roger De Vlaeminck. He finished his career with 19 victories across the Monuments, more than any other rider and eight more than the rider with the second most. He is the only cyclist to win all five Monuments more than once. He won every single-day professional race existing at the time, except for Paris-Tours.

3.2.1. Individual Monument Wins

- Milan-San Remo: 7 wins (1966, 1967, 1969, 1971, 1972, 1975, 1976), a record for a single classic.

- Tour of Flanders: 2 wins (1969, 1975).

- Paris-Roubaix: 3 wins (1968, 1970, 1973).

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège: 5 wins (1969, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975), a record for this race.

- Giro di Lombardia: 2 wins (1971, 1972). (Note: His 1973 victory was disqualified due to doping.)

3.3. World Championship Titles

Merckx won the UCI Road World Championships - Men's road race three times (1967, 1971, 1974), a record he shares with Alfredo Binda, Rik Van Steenbergen, Óscar Freire, and Peter Sagan. Including his amateur world title in 1964, he won four World Championships.

3.4. Hour Record

On 25 October 1972, Merckx set a new hour record at the Agustín Melgar Olympic Velodrome in Mexico City, covering a distance of 31 mile (49.431 km). This record stood for many years and was considered nearly impossible to break. While some later attempts surpassed this distance using specialized aerodynamic bikes, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) later revised its rules to require standard track racing bicycles for the official hour record. Merckx's record, set on a relatively conventional bike for its time, highlights his exceptional physical prowess.

3.5. Triple Crown and Other Unique Feats

Merckx was the first rider to achieve the Triple Crown of Cycling in 1974, by winning the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia, and the UCI Road World Championships in the same calendar year. This feat has only been accomplished two other times, by Stephen Roche in 1987 and Tadej Pogačar in 2024. He is also one of only four riders to have won a Monument, a Grand Tour, and the UCI World Championship in the same year, achieving this in 1971. He holds the record for most Super Prestige Pernod wins with seven victories (1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1975). Other notable records include six wins in the Escalada a Montjuïc, four in the Giro di Sardegna, and two in the Setmana Catalana de Ciclisme. He also excelled in indoor six-day races during winter, winning 17 times.

3.6. Overall Career Statistics

Merckx entered over 1,800 races during his career and won a total of 525, with 445 of those victories as a professional from 1,585 races entered. Between 1967 and 1977, he raced between 111 and 151 races each season. In 1971, he raced 120 times and won 54 events, which remains the most races won by any cyclist in a single season. Due to his overwhelming dominance, some cycling historians refer to the period in which he raced as the "Merckx Era." Merckx himself admitted he was the best of his generation but insisted it is impractical to compare across generations. Given the increasing specialization of cyclists in the modern peloton, it is widely believed that Merckx's total number of road race victories will likely never be surpassed.

4. Racing Style and Philosophy

Eddy Merckx's distinctive approach to racing and his unwavering competitive mindset were central to his unparalleled success and defined his era in cycling.

4.1. "The Cannibal" and Aggressive Racing

Merckx earned the nickname "The Cannibal" (le CannibaleFrench) from the daughter of his teammate, Christian Raymond. Raymond had commented on Merckx's relentless winning, stating that he "wouldn't even leave you the crumbs," to which his daughter replied that Merckx was a cannibal. Raymond liked the nickname and shared it with the press. In Italy, he was also known as il mostro (il mostrothe MonsterItalian). Merckx himself stated that he was never directly called "The Cannibal" by other riders.

Merckx was renowned for his aggressive, attacking style of racing, often described as la course en tête (la course en têtethe race in the leadFrench), a term popularized by a documentary about him. For Merckx, attacking was the best form of defense. He was known for spending an entire day in a breakaway and then launching another significant attack the following day. Despite his constant attacking, he would occasionally adopt a more defensive mindset, particularly when racing the Giro d'Italia against José Manuel Fuente. His relentless pursuit of victory sometimes drew criticism from opposing riders who felt he prevented even lesser-known cyclists from securing a few wins. When asked about winning too much, Merckx famously stated, "The day when I start a race without intending to win it, I won't be able to look at myself in the mirror." He once stated that he aimed to win every stage in the Tour de France. He was merciless not only to others but also to himself. He sometimes attacked first from the peloton despite being advised by the team doctor to stop attacking due to accumulated fatigue. His obsession with victory was tremendous, sometimes even refusing to yield in competitions while playing with his beloved daughter. He often hid the rear sprocket part of his bike from rivals, as its tooth count could reveal his strategy for climbing or sprinting.

4.2. Versatility and Dominance

Merckx's greatness stemmed from his extraordinary versatility, allowing him to excel across all cycling disciplines. He was equally successful in road racing, track cycling, time trials, and climbing. He demonstrated exceptional skill as both a time trialist and a climber. Dutch cyclist Joop Zoetemelk famously remarked, "First there was Merckx, and then another classification began behind him." Cycling journalist and commentator Phil Liggett noted that if Merckx started a race, many riders resigned themselves to competing for second place. Ted Costantino asserted that Merckx was undoubtedly the number one cyclist of all time, unlike other sports where debates about the greatest persist. Gianni Motta recounted how Merckx would ride without a racing cape even in snowy or rainy conditions to gain speed over other riders, showcasing his extreme dedication and competitive edge. He was known as Campionissimo (CampionissimoChampion of ChampionsItalian) by road cycling fans, alongside Fausto Coppi.

4.3. Equipment and Meticulousness

Merckx was known for his meticulousness regarding equipment and position during his career. He would make fine adjustments to his bike right up until the start of a race. There are even legends that he would dismount his bike during a breakaway in a race to call a team mechanic and adjust his saddle height. This attention to detail was partly due to his personality, but also because he suffered from persistent back and waist pain after a severe crash during a track race in 1970, where he also hit his head and was temporarily unconscious.

Early in his career, he disliked the Peugeot frames his team used, so he bought a Masi frame, which he had used to win the amateur World Championships, and painted it in team colors to use at his own expense. When he moved from Peugeot to Faema and then to Molteni, his bikes also changed from Masi to Colnago. Merckx had Ernesto Colnago, the president of Colnago, make an average of 27 frames per year for him. One of these, the bike used in the 1969 Giro, had only 4 gears on the rear sprocket, yet it had two 17-tooth gears, meaning shifting wouldn't change the number of teeth. Furthermore, until the late 1960s, he frequently experimented with bikes where the brake cables were swapped left and right; normally, Merckx used bikes with the front brake on the left and the rear brake on the right, but the bike used in the 1969 Giro had them reversed. From 1974, when Molteni's bikes changed from Colnago to De Rosa, he had Ugo De Rosa, the president of De Rosa, produce 40-50 frames per year for him. In one particular year's Giro, Merckx had a new frame made every day during the last week.

He was also enthusiastic about weight reduction, often drilling holes in parts like gears and handlebars to lighten them. It can be said that the pursuit of lightweight road bikes, which continues to this day, began with Merckx. For his 1972 Hour Record attempt, he used a special Colnago-designed bike weighing just 13 lb (5.75 kg) (compared to the average of 22 lb (10 kg) for road bikes at the time), featuring titanium parts and extensive lightweight modifications.

5. Personal Life

Beyond his professional achievements, Eddy Merckx's personal life has been marked by strong family ties and significant health challenges.

5.1. Family and Marriage

Merckx officially began dating Claudine Acou in April 1965. Acou, a 21-year-old teacher, was the daughter of the national amateur team's trainer. Merckx asked her father for permission to marry her between track races. On 5 December 1967, after four years of courtship, Merckx married Acou. Claudine often handled the press for her shy husband. Their first child, Sabrina, was born on 14 February 1970, with Merckx skipping a team training camp to be with his wife for the birth. Claudine later gave birth to a son, Axel Merckx, who also became a professional cyclist. Eddy Merckx was brought up speaking Flemish but learned French in school. His son Axel's achievements did not match his father's due to his primary role as an assistant, but he had a 15-year career, winning the Belgian Championship and a Giro d'Italia stage in 2000, and a bronze medal at the 2004 Athens Olympics (an Olympic medal being one of the few honors his father could not achieve, as professional cyclists were only allowed to compete in the Olympics from the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, and his father was not eligible except for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics). Axel retired after completing the 2007 Tour de France. When Axel was part of a team, they sometimes used "Eddy Merckx" bikes, or he alone used an "Eddy Merckx" bike even if the team used a different brand.

5.2. Health and Medical Issues

Before the third stage of the 1968 Giro d'Italia, Merckx was found to have a heart condition. A cardiologist, Giancarlo Lavezzaro, diagnosed him with non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition that has been fatal for several young athletes. In 2013, Merckx received a pacemaker to help correct a heart rhythm issue. The surgery, performed in Genk on 21 March 2013, was a preventative measure. Merckx stated that he never experienced heart issues while racing, despite several men in his family dying young from heart-related problems. In May 2004, he underwent an esophagus operation to treat stomachaches that had plagued him since childhood. In August of that year, he reported losing nearly 66 lb (30 kg) after the procedure. On 13 October 2019, Merckx was hospitalized after a cycling accident, suffering a hemorrhage and falling unconscious for a while. He was released a week later. In December 2024, Merckx crashed during a group bike ride and fractured his hip, requiring a full hip replacement. He humorously remarked, "Next time I will ride with training wheels." He was a heavy smoker since his playing days, even having a puff after his Hour Record attempt. This continued after retirement, with him occasionally seen smoking in support cars or official vehicles.

6. Retirement and Post-Career Activities

Following his retirement from professional cycling, Eddy Merckx remained deeply involved in the sport, transitioning into business, coaching, and race organization.

6.1. Eddy Merckx Cycles

After retiring from racing, Merckx founded Eddy Merckx Cycles on 28 March 1980 in Brussels. He sought guidance from Ugo De Rosa, a renowned bike maker, who trained the initial factory workers. Despite facing financial problems, including a near-bankruptcy and a tax repayment controversy, the company gained high regard and success. Its bicycles were used by several top-level cycling teams throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Merckx actively contributed input on the models being produced. He stepped down as CEO in 2008 and sold most of his shares but continued to test the bikes and provide input. As of January 2015, the business remains based in Belgium and distributes to over 25 countries. In the 1970s, Miyata Industrial in Japan also used the Eddy Merckx brand to produce junior sports bikes, road racers, and randonneurs, which, while not a commercial success, laid the groundwork for Miyata's future sports bicycle production.

6.2. Coaching and Race Organization

Merckx managed the Belgian national team for World Championships for eleven years, from 1986 to 1996. He also briefly served as the race director for the Tour of Flanders. He temporarily sponsored a youth developmental team with CGER Bank, where his son Axel raced. He helped organize the Grand Prix Eddy Merckx, which began as an invitation-only individual time trial event before becoming a two-man time trial. The event ceased after 2004 due to a lack of rider interest.

Merckx played a pivotal role in establishing the Tour of Qatar in 2002. In 2001, Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the former Emir of Qatar, expressed interest in starting a bicycle race to showcase his country. Merckx then contacted then-Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) president Hein Verbruggen, who inspected Qatar's roads. Following a successful inspection, Merckx collaborated with the Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO) to plan the race, with an agreement reached in 2001. Merckx officially co-owned the race with Dirk De Pauw and helped organize it until its cancellation before the 2017 edition due to financial reasons. Additionally, Merckx assisted Qatar in securing the right to host the 2016 UCI Road World Championships and designed the race route. Merckx also briefly co-owned and helped launch the Tour of Oman in 2010. However, in November 2017, it was announced that Merckx and Dirk De Pauw had split with ASO, the Tour of Oman organizer, following an undisclosed dispute.

6.3. Ambassadorships

Merckx has served as an ambassador for various charitable organizations, including the Damien The Leper Society, a foundation dedicated to combating leprosy and other diseases in developing countries. He was blessed by Pope John Paul II in Brussels in the 1990s. Merckx is also an art lover, stating that his favorite artist is René Magritte, a surrealist, with Salvador Dalí also among his favorites. In 2015, Merckx remarked that even though he was no longer racing, he would remain involved with the sport "as a bike builder, first in the factory and now as an ambassador."

7. Legacy and Recognition

Eddy Merckx's enduring legacy is rooted in his unparalleled achievements, which have cemented his status as the greatest cyclist of all time and earned him numerous accolades and honors.

7.1. "Greatest Cyclist" Status and Impact

Merckx is widely considered the greatest and most successful cyclist of all time. His ability to excel in both Grand Tours and one-day classics, combined with his exceptional skills as a time trialist, climber, and track cyclist, set him apart. His aggressive racing style, known as la course en tête, contributed to his formidable reputation. During his professional career, he won 445 of the 1585 races he entered, including 54 victories in 1971 alone, a record for most wins in a single season. His dominance was so profound that cycling historians often refer to his era as the "Merckx Era." While Merckx acknowledged his generational superiority, he maintained that cross-generational comparisons are impractical. Given the increasing specialization in modern cycling, it is highly unlikely that his record number of road race victories will ever be surpassed. The French sports newspaper L'Équipe, as expected, chose him as the greatest champion of the Tour on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Tour de France in 2003.

Bernard Hinault, when asked to describe the "ideal cyclist," famously said, "One takes Merckx's legs, Merckx's head, Merckx's muscles, Merckx's heart and Merckx's zeal for victory." Even after his retirement, many subsequent stars have felt overshadowed by his fame and race results. Joop Zoetemelk stated, "First there was Merckx, and then another classification began behind him."

7.2. Awards, Honors, and Titles

Merckx has received numerous honors and awards throughout his career and in recognition of his lasting legacy:

- Titles of Honor:**

- Knight of the French Legion of Honour: 1975

- Officer in the Belgian Order of Leopold II: 1996

- Commander of the French Legion of Honour: 2014

- Knight in the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- Silver Olympic Order: 1995

- Created Baron Merckx by Royal Decree, with the motto Post Proelia Praemia (Post Proelia PraemiaAfter Battles, RewardsLatin): 1996

- Honorary doctorate of the VUB: 2011

- Belgian Olympic and Interfederal Committee Order of Merit: 2013

- Honorary citizen of Meise, Tielt-Winge, and Tervuren

- Bronze Zinneke: 2006

- Sport Awards and Honors:**

- Belgian National Sports Merit Award: 1967

- Belgian Sportsman of the Year: 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974

- Tour de France Overall Combativity award: 1969, 1970, 1974, 1975

- PAP European Sportsperson of the Year: 1969, 1970

- Worldwide Sportsman of the Year: 1969, 1971, 1974

- Grand Prix de l'Académie des Sport: 1969

- Mendrisio d'or: 1972, 2011

- Gan Challenge: 1973, 1974, 1975

- Swiss AIOCC Trophy: 1980, 2021

- Procyclingstats.com - All Time Wins Ranking (1st place, 276 wins)

- Belgian Sportsman of the 20th Century: 1999

- Reuters Worldwide Sports Personality of the Century (7th place): 1999

- Reuters General Sportsman of the Century (2nd place): 1999

- UCI Cyclist of the 20th Century: 2000

- Marca Legend: 2000

- Vincenzo Torriani Award: 2001

- Introduced into the UCI Hall of Fame: 2002

- UCI Top 100 of All Time (1st place, 24,510 points)

- Memoire du Cyclisme - Ranking of the Greatest Cyclists (1st place): 2002

- Bleacher Report - The 30 Most Dominant Athletes of All Time (20th): 2010

- Bleacher Report - Tour de France All-Time Top 25 Riders (1st place): 2011

- Italian Sport and Civilization Award: 2011

- First Member Giro Hall of Fame: 2012

- Topito - Top 15 Greatest Cyclists Ever (1st place): 2012

- L'Équipe Trophée Champion des Champions de Légende: 2014

- Rouleur Hall of Fame: 2018

- Velonews The Greatest Cyclists of All Time (1st place): 2019

- Wiggle The Best Cyclists Ever Rank (1st place): 2020

- Eurosport Greatest General Classification Cyclist of all Time: 2020

- CyclingRanking - Overall Ranking (1st place): 2022

- Vélo d'Or honorary award: 2023

7.3. Places and Monuments

Several public spaces and structures have been named in Merckx's honor:

- Monument in Stavelot: 1993

- Vélodrome Eddy Merckx, Mourenx: 1999

- Eddy Merckx metro station, Brussels: 2003. This station was inaugurated on 15 September 2003 and also displays the Colnago track bike Merckx used to set his Hour Record in 1972.

- Sports complex, Vlaams Wielercentrum Eddy Merckx, Gent: 2006

- Monument in Meise: 2015

- Statue in Meensel-Kiezegem: 2015

- Square Eddy Merckx in Sint-Pieters-Woluwe: 2019

7.4. Events and Awards

- Golden Bike Eddy Merckx: a cycle race for novices from 1983 to 2008.

- Grand Prix Eddy Merckx: a professional cycle race from 1980 to 2004.

- Chiba Alpencup Eddy Merckx Classics.

- The Grand Départ for the 2019 Tour de France was held in Brussels, Belgium, to honor Merckx's first Tour de France win in 1969.

- From 2023, the Vélo d'Or "Eddy Merckx trophy" is awarded for the best classics cyclist.

8. Criticism and Controversies

Despite his celebrated career, Eddy Merckx faced several doping allegations and criticisms regarding his intense competitive nature.

8.1. Doping Allegations and Incidents

Merckx was involved in three separate doping incidents during his career. He strongly criticized doping by athletes, but when Lance Armstrong was suspected of drug use, he was among the first to defend him.

In 1969, Merckx was leading the Giro d'Italia after the sixteenth stage in Savona. After the stage, he underwent a drug test, which was standard for the top two in the general classification and two randomly chosen cyclists. His first test was positive for fencamfamine, an amphetamine, and a second test also confirmed the positive result. The test results were announced to the press before Merckx and his team were informed. The positive test meant Merckx was to be suspended for a month. Race director Vincenzo Torriani delayed the start of the seventeenth stage, attempting to persuade the president of the Italian Cycling Federation to allow Merckx to continue. However, the president was unavailable, and Torriani was forced to start the stage, disqualifying Merckx. Merckx consistently claimed his innocence, stating, "I am a clean rider, I do not need to take anything to win." He had previously tested negative eight times during the race. He argued that his samples had been mishandled. The majority of the international press believed in his innocence, finding it illogical that he would use banned substances on an easy stage when a doping test was certain for the leader. Several conspiracy theories emerged, including that the urine sample was not Merckx's or that he had been given a water bottle containing the stimulant, ostensibly to give Italian rider Felice Gimondi a better chance at victory. In the following days, the UCI removed the suspension.

On 8 November 1973, it was announced that Merckx had tested positive for norephedrine after winning the Giro di Lombardia a month earlier. Upon learning of the first positive test in late October, he had a counter-analysis performed, which also came back positive. The drug was present in a cough medicine prescribed by the Molteni team doctor, Dr. Cavalli. Merckx was disqualified from the race, and the victory was awarded to second-place finisher Gimondi. Additionally, Merckx received a one-month suspension and was fined 150.00 K ITL. He admitted his fault in taking the medicine but stated that the name norephedrine was not on the bottle of cough syrup he used. Norephedrine was later removed from the WADA-list of banned substances.

On 8 May 1977, Merckx, along with several other riders, tested positive for the stimulant pemoline at La Flèche Wallonne. The group was charged by the Belgian cycling federation, and each rider received a 24.00 K ESP fine and a one-month suspension. Merckx initially announced his intention to appeal the penalty, asserting he only took substances not on the banned list. His eighth-place finish in the race was voided. Years later, Merckx admitted he did take a banned substance, citing that he was wrong to have trusted a doctor.

Due to Merckx's positive tests during his career, he was among several riders asked by organizers to stay away from the 2007 UCI Road World Championships in Stuttgart, Germany. The organizers stated they "had to be role models," while Merckx dismissed their actions as "crazy."

9. Popular Culture

Eddy Merckx's widespread fame and achievements have led to his presence and influence in various forms of popular culture, including music, films, comics, and books.

9.1. Music, Films, and Comics

- Music:**

- The single Vas-Y Eddy (1967) by Jean Saint-Paul is notable for being the first recorded song about Merckx.

- Eddy Prend Le Maillot Jaune, a song by Pierre-André Gil, was released after his first Tour de France victory.

- The single Bravo Eddy! by Jean Narcy was released in 1970.

- Eddy Est Imbattable! by Pierre-André Gil was released in 1971.

- Merckx is mentioned in the 1974 song Paris-New York, New York-Paris by Jacques Higelin.

- Eddy Merckx is a song by the Belgian band Sttellla on their 1998 album Il faut tourner l'Apache.

- Films and Series:**

- A 1973 Danish short film, Eddy Merckx in the Vicinity of a Cup of Coffee, starred Merckx and Walter Godefroot.

- In the 1973 comedy film The Mad Adventures of Rabbi Jacob, Merckx was humorously cited by Louis de Funès as the author of Che Guevara's famous quote: "The revolution is like a bicycle: when it doesn't move forward, it falls."

- The 1974 documentary film La Course en Tête by Joël Santoni explored Merckx's racing and private life.

- The 1976 Danish documentary film A Sunday in Hell focused on contenders Merckx, Roger De Vlaeminck, Freddy Maertens, and Francesco Moser in the Paris-Roubaix race of that year.

- Merckx had a cameo in the 1985 sports drama film American Flyers, starring Kevin Costner.

- Merckx is portrayed as a rival to Benoît Poelvoorde in the 2001 film Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert by Philippe Harel.

- In 2005, he appeared in episode 39b of the second season of Space Goofs, where his character provides Earth's core with energy by pedaling a stationary bike.

- Merckx had a cameo in the 2012 French-Belgian comedy film Torpedo by Matthieu Donck.

- The Flemish movie, set in the 1970s, Allez, Eddy was released in 2012.

- Eddy Merckx is the subject of an autobiographical fiction written by Christophe Van Staen, entitled Eddy Merckx, Nobel Prize? (Lamiroy, 2019).

- Comic Books:**

- Les Fabuleux Exploits d'Eddy Merckx, a celebrity comic, was released in 1973 and translated into different languages.

- Eddy Merckx appeared in the comic strip San-Antonio Fait un Tour published by Fleuve Noir in 1973.

- He appeared as a speedy messenger in the comic book Asterix in Belgium of the Asterix series by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, published in 1979.

- A tribute to Eddy Merckx was paid in the 1987 Boule et Bill album no. 24, Billets de Bill.

- Merckx also appeared in album 79 (1988) of the Robert en Bertrand series and album 247 (1996) of the Spike and Suzy series.

- Another tribute was paid in an adventure of Donald Duck, where he competes against his uncle's rival's champion: "Dydy Berkxz." When Lance Armstrong debuted, he didn't know Merckx and, seeing the "Eddy Merckx" logo on the frames used by his Motorola team, reportedly asked, "Who's Eddy Marks (Merckx's English pronunciation)?" surprising those around him with his ignorance of "Campionissimo" Eddy Merckx.

9.2. Books About Merckx

Numerous biographies and books have been written about Eddy Merckx's life and career:

- In English:**

- The Champion Eddy Merckx by Claude le Boul (1987)

- Eddy Merckx: The Greatest Cyclist of the 20th Century by Rik Vanwalleghem and Steven Hawkins (1996)

- Person-Centred Therapy: A European Perspective by Brian Thorne and Elke Lambers (1998)

- Tour de France For Dummies by Phil Liggett, James Raia, and Sammarye Lewis (2005)

- Pedalare! Pedalare! by John Foot (2011)

- Historical Dictionary of Cycling by Jeroen Heijmans and Bill Mallon (2011)

- Eddy Merckx: The Cannibal by Daniel Friebe (2012)

- Eddy Merckx 525 by Frederik Backelandt & Karl Vannieuwkerke (2012)

- Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice by John Nauright and Charles Parrish (2012)

- Merckx: Half Man, Half Bike by William Fotheringham (2012)

- Half Man, Half Bike: The Life of Eddy Merckx, Cycling's Greatest Champion by William Fotheringham (2013)

- The racing bicycle : design, function, speed by Richard Moore and Daniel Benson (2013)

- Merckx 69: Celebrating the World's Greatest Cyclist in his Finest Year by Tonny Strouken and Jan Maes (2015)

- The Dream of Eddy Merckx by Freddy Merckx (2019)

- De Rivals of Merckx by Filip Osselaer (2019)

- 1969 - The Year of Eddy Merckx by Johny Vansevenant (2019)

- In Other Languages:**

- Dutch:** Eddy Merckx (1967), Mijn Wegjournaal (1971), Eddy Merckx Story (1978), Eddy Merckx - Mijn Levensverhaal (1989), Eddy Merckx - De Mens achter de Kannibaal (1993), Spraakmakende biografie van Eddy Merckx (2005), De Mannen achter Merckx : het Verhaal van Faema en Molteni (2006), Fietspassie/La Passion du Vélo (2008), De Zomer van '69, hoe Merckx won van Armstrong (2009), Merckxissimo (2009), Eddy Merckx en Ik - Herinneringen aan de Kannibaal (2010), Eddy Merckx - Getuigenissen van Jan Wauters (2010), Mannen tegen Merckx - van Van Looy tot Maertens (2012), Eddy Merckx - Een leven (2013), Eddy Merckx - De biografie (2015), Eddy! Eddy! Eddy! De Tour in België (2019), 50 jaar Merckx - Jubileum van een Tourlegende (2020).

- French:** L'Irrésistible Ascension d'un Jeune Champion (1968), Merckx ou la Rage de Vaincre (1969), Qui êtes-vous Eddy Merckx? (1969), Du Maillot Arc en Ciel au Maillot Jaune (1970), Le Phénomène Eddy Merckx et ses Rivaux (1971), Face à Face avec Eddy Merckx (1971), Mes Carnets de Route en 1971 (1971), Plus d'un Tour dans Mon Sac: Mes Carnets de Route 1972 (1972), Eddy Merckx cet Inconnu (1972), Les Exploits Fabuleux d'Eddy Merckx (1973, comic book), Mes 50 Victoires en 1973: Mes carnets de route 1973 (1973), Merckx / Ocana : Duel au Sommet (1974), Coureur Cycliste: Un Homme et son Métier (1974), Ma Chasse aux Maillots Rose, Jaune, Arc-en-Ciel: Mes Carnets de route 1974 (1974), Le Livre d'Or de Eddy Merckx (1976), Eddy Merckx l'Homme du Défi (1977), La Roue de la Fortune, du Champion à l'Homme d'Affaires (1989), Eddy Merckx, l'Épopée (1999), Merckx Intime (2002), Eddy Merckx, Ma Véritable Histoire (2006), Eddy Merckx, les Tours de France d'un Champion Unique (2008), Tour 75 : Le Rêve du Cannibale (2010), Dans l'Ombre d'Eddy Merckx - Les Hommes qui ont Couru contre le Cannibale (2012), La fabuleuse histoire du Tour de France (2011), Coup de Foudre dans l'Aubisque: Eddy Merckx dans la Légende (2015), Eddy : Ma Saison des Classiques en Version 1973 (2015), Eddy Merckx, c'est Beaucoup plus qu'Eddy Merckx (2015), Sur les Traces d'Eddy Merckx (2016), La Fabuleuse Carrière d'Eddy Merckx en un Survol (2016), Eddy Été 69 (2019), On m'Appelait le Cannibale (2019), Eddy Merckx : Analyse d'une Légende (2019), Merckx-Ocana: Le Bel Ete 1971 (2021).

- Italian:** E non Chiamatemi (più) Cannibale. Vita e Imprese di Eddy Merckx (2003), Il Sessantotto a Pedali. Al Giro con Eddy Merckx (2008), Fausto Coppi Eddy Merckx. Due campionissimi a confronto (2011), Chiedimi chi Era Merckx. Le Stagioni di Eddy dall'Esordio al Congedo (2013), [https://books.google.com/books?id=bZmfjwEACAAJ Merckx, il Figlio del Tuono] (2016), Gimondi & Merckx. La Sfida (2019).

- German:** Eddy Merckx (1973), Die Nacht, in der Ich Eddy Merckx Bezwang (2019).