1. Overview

Clovis I (ChlodovechusClovisLatin; reconstructed Frankish: *HlōdowigHLO-doh-wigfrk; c. 466 - 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all Frankish tribes under one ruler, transforming a fragmented leadership of petty kings into a single monarchy passed down to his heirs. He is regarded as the founder of the Merovingian dynasty, which governed the Frankish kingdom for the subsequent two centuries. Clovis holds significant importance in the historiography of France as "the first king of what would become France."

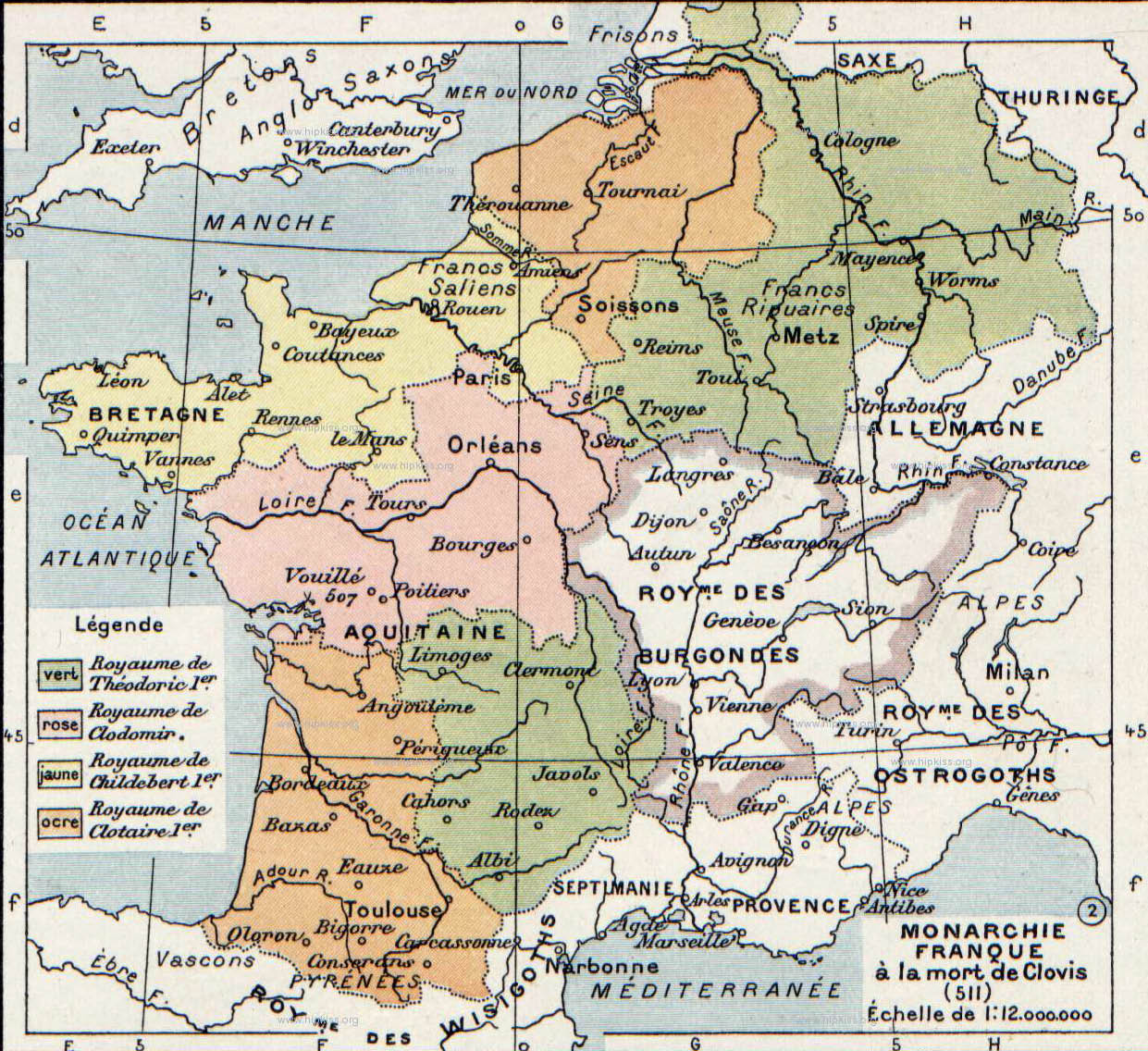

Succeeding his father, Childeric I, as king of the Salian Franks in 481, Clovis expanded his dominion from what is now the southern Netherlands to northern France, encompassing the Roman province of Gallia Belgica. His decisive victory at the Battle of Soissons (486) ended the last vestiges of Roman rule in northern Gaul. By his death in 511, Clovis had conquered numerous smaller Frankish kingdoms, the Alamanni in eastern Gaul, and the Visigothic kingdom of Aquitaine in the southwest. These campaigns significantly enlarged his territories, establishing his dynasty as a dominant political and military force in Western Europe.

Clovis's conversion from paganism to Nicene Christianity (Catholicism) in 508, largely influenced by his wife Clotilde, was a pivotal event. This conversion, in contrast to the Arianism prevalent among most other Germanic tribes, led to widespread religious unification across modern-day France, the Low Countries, and Germany. The enduring alliance between the Franks and the Catholic Church, solidified by Clovis, laid the groundwork for future historical developments, including the crowning of Charlemagne as emperor in 800 and the eventual birth of the early Holy Roman Empire.

2. Name

The name Clovis, deeply rooted in Germanic linguistic history, reflects its bearer's martial prowess and significance.

2.1. Etymology and Variations

The original name is reconstructed in the Frankish language as `*Hlōdowik` or `*Hlōdowig`. This name is traditionally understood to be composed of two Proto-Germanic elements: `*hlūdaz` ("loud, famous") and `*wiganą` ("to battle, to fight"). This etymology leads to the common translation of Clovis's name as "famous warrior" or "renowned in battle."

However, some scholars propose an alternative etymology based on Gregory of Tours' consistent transcription of Merovingian royal names with the first element `chlodo-`. The use of a close-mid back rounded vowel (`o`), rather than the expected close back rounded vowel (`u`) found in other Germanic names recorded by Gregory, suggests that the first element might derive from Proto-Germanic `*hlutą` ("lot, share, portion"). Under this hypothesis, the name would mean "loot bringer" or "plunder (bringing) warrior." This interpretation is supported by the observation that if the first element meant "famous," the name of Clovis's son, Chlodomer, would contain two elements (`*hlūdaz` and `*mērijaz`) both meaning "famous," which is uncommon in typical Germanic name structures.

The name `*Hlodowig` is the origin of the French given name Louis (with the variant Ludovic), famously borne by 18 kings of France, through the Latinized forms `Hludovicus`, `Ludhovicus`, `Lodhuvicus`, or `Chlodovicus`. The English name Lewis derives from the Anglo-French `Louis`.

In Middle Dutch, a language closely related to Frankish, the name was rendered as `Lodewijch` (modern Dutch: `Lodewijk`). Cognates are found in other West Germanic languages, including Old English `Hloðwig`, Old Saxon `Hluduco`, and Old High German `Hludwīg` (variant `Hluotwīg`). The Old High German form evolved into `Ludwig` in Modern German, although Clovis himself is often referred to as `Chlodwig` in German. The Old Norse form `Hlǫðvér` was likely borrowed from a West Germanic language.

3. Background

Clovis I's rise to power occurred within a complex socio-political landscape marked by the decline of Roman authority and the emergence of various Germanic tribes in Gaul.

3.1. Family and Early Life

Clovis was the son of Childeric I, a king of the Salian Franks, and Basina, a Thuringian princess. He was born around 466 in Tournai, which was then a center of Salian Frankish power. The dynasty he founded, the Merovingian dynasty, is named after his supposed ancestor, Merovech. While some sources suggest Chlodio was Clovis's grandfather, Merovech's exact relation to Chlodio remains unclear. According to some accounts, his paternal lineage traces back to the Sicambrian Franks and even to Troy through figures like Polydorus and Helenus. His great-great-grandmother, Protunda, was allegedly a Jewish woman from Septimania.

Details of Clovis's childhood are scarce in primary sources, including the earliest comprehensive account by Gregory of Tours, who wrote about a century after Clovis's death. However, it is believed that Clovis participated in military campaigns against smaller tribes alongside his father from an early age. He succeeded his father as king of the Salian Franks in 481, at the young age of 15. Historians suggest that both Childeric and Clovis served as commanders within the Roman military in the province of Belgica Secunda, subordinate to the magister militum (master of soldiers).

3.2. Frankish Society and Political Climate

The 5th century in Gaul was characterized by numerous small Frankish kingdoms. The Salian Franks were the first known Frankish tribe to settle within the Roman Empire with official permission, initially in Batavia in the Rhine-Maas delta, and then in 375 in Toxandria (modern-day North Brabant in the Netherlands and parts of Antwerp and Limburg in Belgium). This placed them in the northern part of the Roman `civitas Tungrorum`, where the Romanized population remained dominant south of the military highway from Boulogne to Cologne. Later, Chlodio expanded westward to control Roman populations in Tournai, then southward to Artois and Cambrai, eventually extending Frankish influence to the Somme river.

Childeric I, Clovis's father, was a prominent Frankish king in northern Gaul, known for his military prowess. In 463, he collaborated with Aegidius, the magister militum of northern Gaul, to defeat the Visigoths at Orléans. The Franks of Tournai, initially aided by their association with Aegidius, began to dominate their neighbors.

The assassination of Aetius in 454 marked a significant decline in imperial power in Gaul, leading to a power vacuum where the Visigoths and the Burgundians vied for control. The remaining Roman-controlled territory in Gaul coalesced into a rump state under Syagrius, Aegidius's son. Although no direct primary sources detail the language spoken by Clovis, historical linguists widely believe that, given his family's origins and core territories, he likely spoke a form of Old Dutch. This contrasts with later Carolingian rulers like Charlemagne, who probably spoke various forms of Old High German.

4. Early Reign and Consolidation of Power

Clovis's early reign was characterized by strategic alliances and decisive military actions that laid the groundwork for his extensive conquests and the unification of the Frankish tribes.

4.1. Succession and Early Campaigns

Upon the death of his father, Childeric I, in 481, Clovis succeeded to the throne of the Salian Franks at the age of 15. His initial force was modest, likely consisting of no more than five hundred warriors. In 486, Clovis began his efforts to expand his realm by forming alliances with other Frankish `reguli` (petty kings), including his relative Ragnachar, king of Cambrai, and Chalaric. These early campaigns aimed to establish dominance over neighboring Frankish groups and consolidate his position.

4.2. Battle of Soissons (486)

The pivotal moment in Clovis's early reign was the Battle of Soissons (486). Clovis, allied with Ragnachar and Chalaric, marched against Syagrius, the Gallo-Roman commander who ruled the last remnant of Roman authority in northern Gaul, known as the Domain of Soissons. During the battle, Chalaric betrayed his allies by refusing to engage in the fighting. Despite this defection, the Franks achieved a decisive victory, forcing Syagrius to flee to the court of Alaric II, the Visigothic king. This battle is widely considered to mark the definitive end of Roman rule in Gaul outside of Italy.

Following the victory, Clovis invaded Chalaric's territory and imprisoned him and his son. A notable incident after the battle, recounted by Gregory of Tours, involved a valuable ewer taken from the Church of Reims during the Franks' pillaging of Roman territory. When Bishop Remigius of Reims requested its return, Clovis agreed, seeking to establish good relations with the clergy. During the division of spoils at Soissons, Clovis asked for the ewer in addition to his allotted share. A Frankish warrior defied him, smashing the vase with his axe. Clovis, though outwardly calm, later confronted the warrior at a military review, criticizing his unkempt weapons and striking him down with an axe, declaring, "Thus did you treat the vase at Soissons!" This act, approved by the Church, instilled fear and absolute obedience among his subordinates.

4.3. Consolidation in Gaul

After the Battle of Soissons, Clovis focused on integrating the newly acquired Roman territories and populations. Recognizing the necessity of clerical support for effective governance, he sought to establish cordial relationships with the Gallo-Roman clergy. He returned the ewer to Bishop Remigius and later married Clotilde, a Catholic princess, to further appease them.

Despite his growing power, some Roman cities initially resisted Frankish rule. Verdun surrendered after a brief siege, while Paris stubbornly held out for several years, possibly as many as five. Clovis eventually made Paris his capital and established an abbey dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul on the south bank of the Seine, which was later renamed Sainte-Geneviève Abbey. He also integrated many of Syagrius's former military units into his own army, strengthening his forces. By 491, Clovis had likely secured control over the former Roman kingdom, as evidenced by his successful campaign against a small group of Thuringians in eastern Gaul near the Burgundian border that same year.

5. Military Campaigns and Expansion

Clovis's reign was marked by a series of strategic military campaigns and alliances that significantly expanded the Frankish kingdom, transforming it into a dominant power in Gaul.

5.1. Alliance with the Ostrogoths

Around 493, Clovis solidified a crucial alliance with the powerful Ostrogoths through a diplomatic marriage. His sister, Audofleda, was married to their king, Theodoric the Great. This alliance secured the eastern flank of the burgeoning Frankish realm, allowing Clovis to focus on other expansionist endeavors.

5.2. Conflict with the Alamanni

In 496, the Alamanni invaded Gaul, causing some Salian and Ripuarian Franks `reguli` (kings) to defect to their side. Clovis confronted the Alamanni near the strong fort of Tolbiac. The Franks suffered heavy losses during the initial fighting. It was during this critical juncture that Clovis, along with over three thousand Frankish companions, may have converted to Christianity, seeking divine intervention. With the crucial assistance of the Ripuarian Franks, Clovis narrowly defeated the Alamanni in the Battle of Tolbiac in 496. This victory solidified his control over eastern Gaul and had profound implications for his religious conversion.

5.3. Intervention in Burgundy

Around 500 or 501, civil strife erupted in the neighboring Burgundian kingdom. King Chilperic II was slain by his brother, Gundobad, who then allegedly drowned his sister-in-law and forced his niece, Chrona, into a convent. Another niece, Clotilde, fled to the court of Gundobad's third brother, Godegisel. Godegisel, finding himself in a precarious position, formed an alliance with Clovis by arranging the marriage of his exiled niece, Clotilde, to the Frankish king.

In 500 or 501, Godegisel began plotting against Gundobad, promising Clovis territory and annual tribute in exchange for his brother's defeat. Eager to neutralize a political threat and expand his influence, Clovis crossed into Burgundian territory. Gundobad then moved against Clovis, calling upon his brother Godegisel for reinforcements. The three armies met near Dijon, where the combined forces of the Franks and Godegisel defeated Gundobad, who managed to escape to Avignon. Clovis pursued him and laid siege to the city. After several months, Clovis was persuaded to abandon the siege, settling instead for an annual tribute from Gundobad, thus gaining significant political influence in Burgundy.

5.4. War against the Visigoths

In 501, 502, or 503, Clovis led his troops into Armorica, aiming for its subjugation. Initially, his operations were limited to minor raids, but he soon realized that military means alone would not suffice. He resorted to diplomacy, which proved fruitful as the Armorici shared Clovis's disdain for the Arian Visigoths. Consequently, Armorica and its fighters were integrated into the Frankish realm, providing valuable allies for future campaigns.

In 507, with the consent of his magnates, Clovis launched an invasion against the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse, which posed a significant threat. Although King Alaric II had previously attempted to establish cordial relations with Clovis by delivering the head of the exiled Syagrius in 486 or 487, Clovis could no longer resist the opportunity to move against the Visigoths. Many Catholics living under Visigothic rule were discontent and implored Clovis to intervene. To ensure the loyalty of these Christians, Clovis explicitly ordered his troops to refrain from raiding and plundering, framing the campaign as a liberation rather than a foreign invasion.

The Armorici provided crucial assistance in the decisive Battle of Vouillé in 507, which effectively eliminated Visigothic power in Gaul. The battle resulted in the death of Visigothic King Alaric II and added most of Aquitaine to Clovis's kingdom. According to Gregory of Tours, following this victory, the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I bestowed upon Clovis the honorary titles of patrician and consul. This entirely Roman ceremony, where Clovis donned imperial purple robes and a crown sent by the emperor at the Church of Saint Martin in Tours, and then paraded through the city to the cheers of "Long live the Consul, Long live the Augustus," served to legitimize his rule over Gaul in the eyes of the Roman world. From that day, he was referred to as Consul or Augustus. These events indicate that the Western Roman Empire, though under Germanic rule, continued to exist in legal and popular consciousness. However, the honor granted to Clovis was comparatively minor compared to the title of "Caesar" or "Augustus" given to the Ostrogothic king Theodoric.

6. Unification of the Franks

Following the Battle of Vouillé and the significant expansion of his territory, Clovis systematically eliminated his rivals and consolidated his rule over all Frankish peoples, ensuring the Merovingian dynasty's dominance.

6.1. Subjugation of Petty Kings

Clovis's strategy for unifying the Franks involved not only military conquest but also cunning political maneuvers and ruthless elimination of competing Frankish leaders. He gradually absorbed smaller Frankish kingdoms and leaders, often through a combination of force, deception, and bribery.

6.2. Elimination of Rivals

Clovis was particularly adept at removing political opponents, even those who were his relatives or former allies.

- Chararic**: Sometime after 507, Clovis learned of Chararic's plan to escape from his monastic imprisonment. Clovis had him murdered to prevent any resurgence of his influence.

- Chlodoric**: Clovis orchestrated the murder of Sigobert, the king of the Ripuarian Franks in Cologne, by convincing Sigobert's son, Chlodoric, to commit patricide. Chlodoric earned his nickname "the Parricide" for this act. After the murder, Clovis betrayed Chlodoric, sending envoys who struck him down. Clovis then claimed Sigobert's kingdom, telling the Ripuarian Franks that he had avenged their dead king and had no involvement in his death, a claim the populace welcomed.

- Ragnachar**: Clovis also targeted his old ally, Ragnachar, king of Cambrai. After Clovis's conversion to Christianity in 508, many of his pagan retainers had defected to Ragnachar, making him a political threat. When Ragnachar denied Clovis entry into Cambrai, Clovis moved against him. He bribed Ragnachar's retainers to betray him during battle. When Ragnachar was captured and brought before Clovis, Clovis reportedly scorned him for allowing himself to be bound, then split his skull with an axe, stating that Ragnachar had disgraced their family. Ragnachar's brother, Ricchar, was also executed. The bribed warriors later discovered their "gold" armbands were merely gilded bronze. When they protested, Clovis warned them that those who betray their lord do not deserve real gold and should be grateful to have escaped execution.

- Rignomer**: Clovis also eliminated Ragnachar's brother, Rignomer, who ruled Le Mans.

By systematically removing these rival Frankish kings, Clovis ensured that the Merovingian dynasty would not be threatened by other branches of the Frankish royal families, a strategy that contributed to the dynasty's longevity for nearly three centuries.

7. Conversion to Christianity

Clovis's conversion from paganism to Nicene Christianity was a momentous event with profound political and religious implications for the nascent Frankish kingdom and for the future of Western Europe.

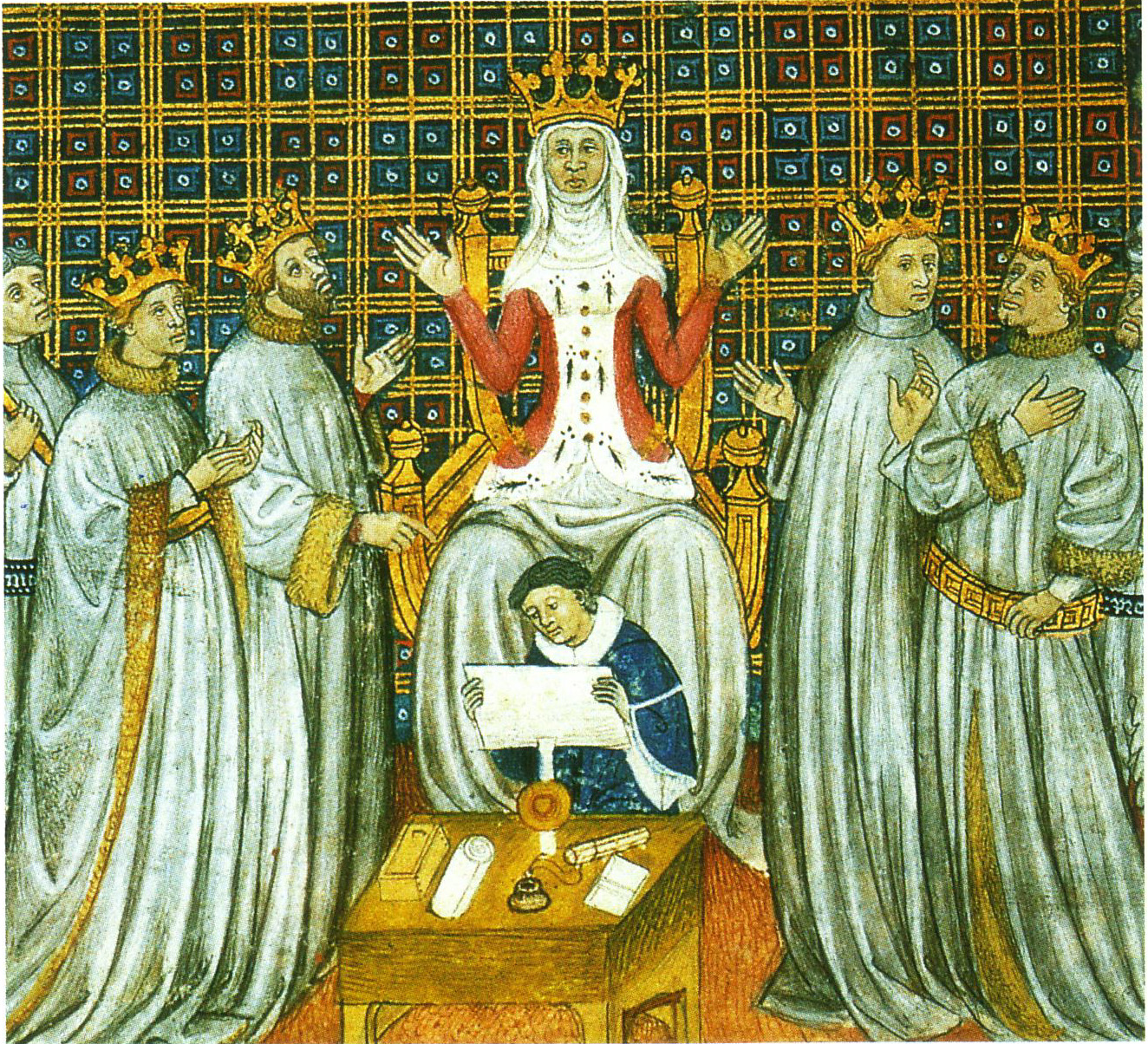

7.1. Influence of Queen Clotilde

Clovis was born a pagan. His wife, Clotilde, a Burgundian princess, was a devout Nicene Christian, despite the prevalence of Arianism at her own court. She persistently advocated for Clovis's conversion, though he initially resisted. Clotilde secretly had their first son baptized without Clovis's knowledge, but the child died shortly after, which only strengthened Clovis's reluctance. She then had their second son baptized, again without his permission, and this son also fell ill and nearly died after his baptism. Despite these setbacks, Clotilde's unwavering faith and influence ultimately played a decisive role in Clovis's decision to convert.

7.2. Adoption of Nicene Christianity

Clovis's conversion was to Nicene Christianity (Catholicism), rather than the Arian form of Christianity adopted by most other Germanic tribes, such as the Visigoths and the Vandals. Arianism held that Jesus was a distinct and separate being from God the Father, subordinate to and created by Him, a theological stance declared a heresy at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In contrast, Nicene Christianity, as championed by the Catholic Church, affirmed the consubstantiality of God the Father, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit as three persons of one being.

While the missionary work of Bishop Ulfilas had converted a significant portion of the pagan Gothic Arians to Arian Christianity in the 4th century, making Gothic Arians dominant in Christian Gaul by Clovis's time, his embrace of Catholicism offered significant advantages. It distinguished his rule from that of other Germanic kings and garnered him the crucial support of the Catholic Gallo-Roman aristocracy and clergy, which proved invaluable in his campaigns, particularly against the Visigoths. Although Clovis was not the first Germanic king to convert to Nicene Christianity (that distinction belongs to Rechiar, the Suevic king of Gallaecia, whose conversion predates Clovis's by half a century), his conversion was immensely significant due to the vast territorial expansion of his dominion over Gaul.

7.3. Significance of the Baptism

Clovis was baptized on Christmas Day, likely in 508, in a small church near the site of the later Abbey of Saint-Remi in Reims. A statue depicting his baptism by Saint Remigius can still be seen there. The details of this event were recorded by Gregory of Tours many years later in the 6th century.

The king's Nicene baptism had immense importance for the subsequent history of Western and Central Europe. It led to widespread conversion among the Franks and eventually to religious unification across what is now modern-day France, the Low Countries, and Germany. This alliance between the Franks and Catholicism eventually culminated in Charlemagne's crowning by the Pope as emperor in 800, and the subsequent birth of the early Holy Roman Empire in the middle of the 10th century.

Some historians, like Bernard Bachrach, have argued that Clovis's conversion from Frankish paganism initially alienated many of the other Frankish sub-kings and temporarily weakened his military position. Gregory of Tours, in his `interpretatio romana`, equated the Germanic gods abandoned by Clovis with Roman deities like Jupiter and Mercury. Other scholars, like William Daly, have critically assessed Clovis's allegedly barbaric and pagan origins, relying on earlier, scarcer sources such as a 6th-century `vita` of Saint Genevieve and letters from bishops and Theodoric concerning Clovis.

Clovis and his wife, Clotilde, were eventually buried in the Abbey of St Genevieve (originally the Church of the Holy Apostles) in Paris.

8. Administration and Law

Clovis's reign not only saw significant territorial expansion but also the establishment of foundational administrative and legal structures that helped solidify the Frankish kingdom and integrate its diverse populations.

8.1. Establishment of the Frankish Kingdom

Following his military successes, particularly the Battle of Vouillé, Clovis is credited with founding the unified Frankish kingdom. He chose Paris as his capital around 508, giving the city symbolic weight as the fixed center of the dynasty. He also established an abbey dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul on the south bank of the Seine, which was later renamed Sainte-Geneviève Abbey in honor of the patron saint of Paris. This act contributed to the formation of a new political entity in Gaul, distinct from the fragmented tribal leaderships that preceded it.

8.2. Codification of Salic Law

Under Clovis's rule, the first codification of the Salian Frankish law took place, resulting in the `Lex Salica` or Salic Law. This legal code was developed with the assistance of Gallo-Romans, reflecting an integration of traditional Salian Frankish customs with elements of Roman legal traditions and Christian principles. The Salic Law meticulously listed various crimes and their corresponding fines, providing a standardized legal framework for the kingdom.

8.3. Relations with the Gallo-Roman Elite and the Church

Clovis pursued a policy of integrating the existing Gallo-Roman aristocracy and clergy into his administration. His conversion to Catholicism was a key factor in fostering cooperation with the Church, which held significant influence over the Gallo-Roman population. This alliance provided him with administrative support and legitimacy among the Romanized inhabitants of Gaul.

Shortly before his death, in 511, Clovis convened the First Council of Orléans. This synod of Gallic bishops aimed to reform the Church and forge a strong link between the Frankish Crown and the Catholic episcopate. Thirty-three bishops attended, passing 31 decrees concerning individual duties and obligations, the right of sanctuary, and ecclesiastical discipline. These decrees, applicable to both Franks and Romans, marked a significant step towards establishing equality between the conquerors and the conquered, and reinforced the king's authority over the Church within his realm.

8.4. Imperial Titles and Recognition

As a testament to his growing power and strategic diplomacy, Clovis received honorary titles from the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius I. Following the Battle of Vouillé, the Emperor bestowed upon him the titles of patrician and honorary consul. This imperial recognition, which involved a formal ceremony in Tours where Clovis wore imperial purple robes and a crown, served to legitimize his rule in the eyes of the Roman world and provided a powerful symbolic endorsement of his authority. While some contemporary inscriptions suggest that the Ostrogothic king Theodoric also received the title of "Augustus," Clovis's recognition, though perhaps less prestigious than a full imperial title, nonetheless affirmed his standing within the post-Roman European order.

9. Death and Succession

Clovis I's death in 511 marked the end of an era of unprecedented Frankish expansion and unification, but also initiated a pattern of kingdom division that would characterize much of the Merovingian period.

9.1. Death

Clovis I is traditionally said to have died on 27 November 511. This date is found in medieval calendars and missals from the Abbey of Saint Genevieve, which Clovis himself founded. However, other obituaries from the abbeys of Saint Genevieve and Saint Denis indicate alternative dates, such as 29 November and 3 January, respectively. The 3 January date might be a confusion with the feast day of Genevieve. Gregory of Tours states that Clovis died in the fifth year after the Battle of Vouillé, which, using inclusive counting, would place his death in 511. He is last attested in an official document dated 11 July 511, relating to the First Council of Orléans, and it is generally accepted that he died shortly thereafter.

Clovis was initially laid to rest in the Abbey of St Genevieve (also known as the Church of the Holy Apostles) in Paris. His remains were later relocated to the Saint Denis Basilica in the mid to late 18th century.

9.2. Partition of the Kingdom

Upon Clovis's death, his vast kingdom was partitioned among his four surviving sons: Theuderic, Chlodomer, Childebert, and Clotaire. This division was carried out according to traditional Frankish custom, particularly the Salic Law, which dictated the equal inheritance of property among male heirs.

This partition created new political units, effectively establishing the Kingdoms of Rheims, Orléans, Paris, and Soissons. While Clovis had ruled as a king with no fixed capital and a relatively centralized administration, his decision to be interred in Paris gave the city significant symbolic weight. Fifty years after his death, when his grandchildren again divided royal power, Paris was retained as a joint property and a permanent symbol of the dynasty.

However, this precedent of dividing the kingdom among sons led to significant internal discord and disunity, a pattern that persisted throughout the Merovingian dynasty until its end in 751. This fragmentation continued under the Carolingians as well, until a brief period of unity under Charlemagne. Ultimately, the Franks splintered into distinct spheres of cultural influence, coalescing around Eastern and Western centers of royal power, which later evolved into the Kingdom of France, the various German States, and the semi-autonomous kingdoms of Burgundy and Lotharingia.

10. Legacy and Assessment

Clovis I's reign left an indelible mark on the course of European history, establishing the foundations of the Frankish kingdom and profoundly influencing the political and religious landscape of the early Middle Ages.

10.1. Founder of the Frankish Kingdom and France

Clovis's most enduring legacy is his role as the unifier of the Franks. He transformed a collection of disparate Frankish tribes and petty kingdoms into a single, cohesive political entity that encompassed most of Roman Gaul and parts of western Germany. This unified Frankish kingdom, established under his rule, is widely regarded by many French people as the foundational precursor to the modern French state. His strategic conquests and the consolidation of power laid the essential groundwork for the future development of France as a distinct nation.

10.2. Impact on Western Europe and Christianity

Clovis's conquests significantly reshaped the geopolitical map of Western Europe. By defeating the last Roman ruler in Gaul, the Alamanni, and the Visigoths, he secured Frankish dominance over a vast territory. Equally, if not more, impactful was his conversion to Nicene Christianity. This decision, in contrast to the Arian faith of most other Germanic rulers, forged a powerful and lasting alliance between the Frankish monarchy and the Catholic Church. This alliance provided the Franks with immense legitimacy and support from the Gallo-Roman population and clergy, facilitating the integration of Roman and Germanic elements within his kingdom. His conversion fostered widespread religious unification, contributing to the Christianization of Western Europe and setting the stage for the close relationship between the papacy and future Frankish rulers, most notably Charlemagne, whose crowning by the Pope symbolized the emergence of a new Christian empire in the West.

10.3. Veneration as a Saint

In later centuries, Clovis was venerated as a saint in France, despite lacking official canonization by papal authority. His sainthood was primarily recognized through popular acclaim and local cults. Shrines dedicated to Saint Clovis existed in significant religious centers, including the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Denis (where he was buried) and the Abbey of Saint Genevieve in Paris. The veneration of Saint Clovis was particularly strong in southern France, with monasteries like Moissac Abbey claiming to be founded by him and many others named in his honor. Abbot Aymeric de Peyrat (d. 1406), author of the History of Moissac Abbey, not only referred to Clovis as a saint but also prayed for his intercession. Shrines were also known in Église Sainte-Marthe de Tarascon and Saint-Pierre-du-Dorât.

The reasons for the promotion of Clovis's veneration are debated. Some suggest it was a state-sponsored effort to establish a "border cult" in the south, encouraging Occitans to venerate the northern-led French state by honoring its founder. Others propose that Clovis served as a more suitable foundational figure for the House of Valois compared to Charlemagne, whose veneration was already widely recognized. Conversely, some argue that Occitans used the cult of Saint Clovis to assert their autonomy against the northern concept of monarchy.

As a saint, Clovis represented a more militarized royal figure compared to the pious Louis IX of France. He symbolized the spiritual birth of the nation and provided a chivalrous and ascetic model for French political leaders. His veneration extended beyond France, with depictions of "St. Chlodoveus" in works by Holy Roman woodcut designers like Leonhard Beck for the Habsburg monarchy, in St. Boniface's Abbey in Munich, and in paintings by Florentine Baroque artist Carlo Dolci for the Uffizi Gallery.

Despite his popular veneration, Clovis was never officially canonized or beatified. His feast day in France was observed on 27 November. French monarchs, starting in the 14th century, repeatedly attempted to formally canonize Clovis, notably King Louis XI during a conflict with the Burgundians. In the 17th century, the Jesuits renewed efforts for his formal canonization, providing a `vita` (hagiography) and accounts of posthumous miracles, in opposition to Calvinist pastor Jean de Serres who portrayed Clovis as cruel and bloodthirsty. This period saw a resurgence of Clovis's cultus, emphasizing his dual role as a deeply sinful man who achieved sainthood through submission to God's will and as the founder of the Gallican Church. Protestant Gallicans viewed Clovis as a symbol of the monarchy's role in governing the Church without papal authority, while Catholic writers expanded on his miracles, though some later minimized their miraculous elements. The Spanish Monarchy's use of the title "Catholic Monarchs" also spurred French monarchs to attribute this title to Clovis, seeking to usurp its prestige.

10.4. Historical Evaluation and Controversies

Clovis's legacy, a Frankish kingdom encompassing most of Roman Gaul and parts of western Germany, endured long after his death. To many French people, he is considered the founder of the modern French state.

However, his reign is not without controversy. While recognized for his unifying achievements, criticisms often focus on his ruthless methods of consolidating power, including the systematic elimination of rival Frankish kings through cunning and violence. Historians like Gregory of Tours, writing about a century after Clovis, often portrayed him as a second Constantine the Great, emphasizing his conversion and its benefits for the Church. However, modern scholarship acknowledges the challenges in relying solely on Gregory's chronology, which is often inconsistent and may have been fabricated to present a particular narrative.

The division of his kingdom among his sons, motivated by the Frankish custom of equal inheritance, also detracted from his legacy. This partition, not based on national or geographical lines, led to significant internal discord and set a precedent for future fragmentation, ultimately contributing to the decline of the Merovingian dynasty. Nevertheless, Clovis bequeathed to his heirs the crucial support of both the people and the Church, a foundation that proved vital for the subsequent development of the Frankish realm and its eventual transformation into the Kingdom of France.