1. Overview

Clotilde (also known as Clotilda, ChlothildeKLOHT-hil-deGerman, Chrodechildiskroh-DEH-khil-disLatin, Chlodechildiskloh-DEH-khil-disLatin, Chlothieldis, Chlotichilda, Clodechildis, Croctild, Crote-hild, Hlotild, or Rhotild), born around 474 or 475 and died in 544 or 545, was a princess of the Burgundian kingdom and the second wife of Clovis I, the first King of the Franks. Veneration as a saint by both the Roman Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church, she played a pivotal role in her husband's conversion to Catholicism, which had a profound and lasting impact on the Frankish kingdom, shaping its religious future for centuries. In her later years, she became renowned for her extensive almsgiving and charity work, establishing numerous churches and monasteries. Despite facing significant personal tragedies and political intrigue, including the murder of her parents and disputes within her own family, Clotilde remained steadfast in her faith and commitment to the welfare of others. She is the patron saint of the lame in Normandy, Les Andelys, queens, widows, brides, and exiles, and is invoked against sudden death and abusive husbands. Her feast day is traditionally celebrated on June 3.

2. Early Life and Family Background

Clotilde's early life was marked by her aristocratic lineage within the Burgundian kingdom and the turbulent political landscape of her time.

2.1. Birth and Family

Clotilde was born around 474 or 475, likely in Lyon, then part of the Burgundian kingdom. Her father was Chilperic II of Burgundy, and her mother was Caretena, who was described as "a remarkable woman" and may have converted her husband to Christianity. Clotilde's grandfather was Gondioc, who died in 473. Upon Gondioc's death, his four sons-Gundobad, Chilperic II, Gondemar, and Godegisel-divided the Burgundian inheritance among themselves. Chilperic II reportedly ruled from Lyon, Gundobad from Vienne, and Godegisel from Geneva.

The Burgundian political scene was fraught with violence. Accounts, particularly by Gregory of Tours, suggest that Gundobad murdered his brothers, including Chilperic II, in 493, and had Chilperic's wife, Caretena, drowned with a stone tied around her neck. While this narrative became a popular theme in later epic stories, some historians, including Godefroid Kurth, consider it apocryphal or a later fabrication, suggesting the original facts were materially altered over time. However, it is consistently stated across sources that Clotilde's family suffered greatly from these internal conflicts. Clotilde had a sister, Sedeleuba (also known as Chrona), who later became a nun and established the church of Saint-Victor in Geneva.

2.2. Upbringing and Education

After her parents' deaths, Clotilde and her sister were raised at the court of Gundobad. Despite Gundobad and most of the Burgundian kings adhering to Arianism-a form of Christianity considered heterodox by the Catholic Church-Clotilde received a Catholic education. She developed a strong sense of piety and compassion for the suffering from an early age, characteristics that would define her life and influence her future actions.

3. Marriage to Clovis I and Conversion to Christianity

Clotilde's marriage to Clovis I was a pivotal event that profoundly influenced the religious landscape of the Frankish kingdom, leading to its conversion to Catholicism.

3.1. Marriage to Clovis I

Clotilde married Clovis I, the first king of the Franks, in either 492 or 493, shortly after the death of her mother. Clovis, who had recently consolidated control over Northern Gaul, was reportedly impressed by Clotilde's beauty and wisdom. Their union, viewed from the 6th century onwards, became the subject of various epic narratives, which often embellished or altered the original historical facts. Clotilde's story captivated later generations as it represented "the centerpiece of a struggle between the old Catholic, Roman population against the Arianism of the Germanic tribes." While some sources suggest this struggle, there is no definitive evidence that Clovis himself was an Arian sympathizer before his marriage and eventual conversion to Catholicism.

3.2. Influence on Clovis I's Conversion

Clotilde was raised in the Catholic faith and actively encouraged Clovis to abandon his pagan beliefs or Arian leanings and embrace Catholicism. She persistently urged him to convert, although he initially resisted. She baptized their first son, Ingomir, who tragically died in infancy. Clovis reportedly blamed Ingomir's death on Clotilde's faith, which fueled his reluctance. However, when their next son, Clodomir, was also baptized and subsequently fell ill, he recovered, which seemed to lessen Clovis's skepticism.

The turning point came in 496, during the Battle of Tolbiac against the Alamanni. With his army on the verge of defeat, Clovis desperately prayed to "Clotilde's God," vowing to convert to Christianity if granted victory. According to tradition, as Clovis began to win the battle, an angel appeared to Clotilde, bringing her three white lilies. Clovis later replaced the three frogs on his battle shield insignia with these lilies. True to his vow, Clovis entered the Catholic Church and was baptized by Saint Remigius in Reims on Christmas Day of 496, along with 3,000 of his Frankish warriors. This event marked a monumental shift, establishing the Franks as a Catholic kingdom for centuries and significantly contributing to the spread of Christianity in the Western world. Historian Sabine Baring-Gould suggests that Clovis's conversion was sincere, not merely a political maneuver, and disputes claims that Clotilde incited him to war for revenge.

3.3. Children

Clotilde and Clovis I had several children, including four sons and one daughter:

- Ingomer** (born 494): Their first son, who died in infancy shortly after baptism.

- Chlodomer** (495-524): Became King of the Franks in Orléans from 511.

- Childebert I** (496-558): Became King of the Franks in Paris from 511.

- Chlothar I** (497-561): Became King of the Franks in Soissons from 511, and eventually King of all Franks from 558.

- Clotilde** (500-531): Named after her mother, she married Amalaric, the King of the Visigothic Kingdom. Her mother reportedly tried unsuccessfully to convert him to Catholicism, and he treated her cruelly. She died on her way to Paris after her brother Childebert retaliated and rescued her from her husband.

Clovis also had an older son, Theuderic I, whose mother is debated, but he received a significant portion of the inheritance after Clovis's death.

4. Later Life and Activities

After the death of Clovis I, Clotilde largely withdrew from direct political involvement, dedicating herself to religious devotion and extensive charitable works, though her life continued to be intertwined with the tumultuous affairs of the Merovingian dynasty.

4.1. Life as a Widow and Retreat

Clovis I died in 511, and Clotilde buried him at the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Paris, which later became the Church of Sainte-Geneviève. This church, which they had begun together as a mausoleum honoring Saint Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris, was completed by Clotilde after Clovis's death. Genevieve herself may have initially suggested to Clovis that he build a church honoring Saint Peter and Saint Paul, which he constructed in deference to Clotilde's wishes.

After Clovis's death and the subsequent tragedies involving her grandchildren, Clotilde left Paris and retreated to Tours, where she spent most of her remaining years near the tomb of Saint Martin of Tours. She became closely associated with the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tours, dedicating herself to a devout life. She was said to be "totally detached from politics and power-struggles except through prayer" and devoted herself to praying, fasting, weeping, and giving all her possessions to the poor.

4.2. Charitable Activities and Foundations

Clotilde was a prolific founder of religious institutions and a dedicated philanthropist. She oversaw the construction of numerous churches, monasteries, and convents. Among her notable foundations was the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Paris, built with Clovis, which later became the Church of Sainte-Geneviève. She also founded the monastery of St. Mary of Les Audelys in Touraine and a monastery for nuns in Chelles, dedicated to Saint George. The Chelles monastery became wealthy and served for centuries as an important center of education for English princesses, descendants of Clovis and Clotilde.

Reportedly, she built churches in Rouen, Lyon, and Les Andelys. In 511, she established a convent for young noble girls in Les Andelys, where a collegiate church now stands. A popular local tradition tells of a miracle at Les Andelys during the convent's construction: when workers complained of heat and thirst, Clotilde prayed, and water from a nearby fountain miraculously "had the power and the taste of wine for the workers." This spring, now known as Saint Clotilde's Fountain, gained renown for its healing properties, particularly for skin diseases, and became a destination for pilgrims seeking cures.

4.3. Role in Family Disputes and Political Events

Despite her withdrawal from overt political life, Clotilde's presence remained significant in the "violent Merovingian world," often through her interactions with her sons. Historical accounts differ on her involvement in family conflicts.

One epic narrative about the Franks claims that Clotilde incited her son Chlodomer to wage war against his cousin, Sigismund of Burgundy, as a means of avenging the murder of her parents by Sigismund's father, Gundobad. In 523, her sons indeed went to war against Sigismund, leading to his deposition, imprisonment, and subsequent murder the following year, his body thrown into a well as symbolic revenge. While Gregory of Tours' writings support Clotilde's instigation, historians like Godefroid Kurth cast doubt on this story, considering it a defamation against Clotilde and suggesting it is unconvincing or apocryphal. They argue that Clotilde had previously arranged a truce between Clovis and Gundobad, which contradicts such vengeful actions, and that later sources have "vindicated the queen from charges of ferocity and vindictiveness, little in keeping with her saintly character."

Further tragedy struck when Chlodomer himself was killed in a subsequent Burgundian campaign by Godomar, Sigismund's heir. Clotilde adopted Chlodomer's three young sons, attempting to protect their rights, but was reportedly induced to send them to her other surviving sons, Childebert and Chlothar, who ruthlessly killed the two oldest for territorial gain. Only the youngest boy, Clodoald, was saved, escaping to become a monk in Paris at a monastery in Nogent-sur-Marne, which was later renamed in his honor. Clotilde's efforts to prevent civil strife among her sons ultimately failed.

Her daughter, also named Clotilde, suffered cruel treatment from her Visigothic husband, Amalaric. After receiving a blood-stained veil from her daughter, Clotilde's son Childebert retaliated against Amalaric, pillaging his towns and rescuing his sister. However, the younger Clotilde died on the way back to Paris. Despite these trials and the failure to prevent conflicts, Gregory of Tours also recorded that Clotilde's prayers were believed to have miraculously delayed a war between her two surviving sons, causing a tempest that forced armies to abandon operations.

5. Death

Clotilde died in Tours on June 3, 545, after living as a widow for 34 years. Some sources indicate her death occurred in 544 or 545. She was buried alongside Clovis and her older children at the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Paris, which is now known as the Church of Sainte-Geneviève. Her daughter also died around the same time.

6. Legacy and Veneration

Saint Clotilde's life and actions left a significant and enduring legacy, influencing Christianization, religious patronage, and artistic representation for centuries.

6.1. Veneration and Patronages

Clotilde is venerated as a saint by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church, with her feast day celebrated annually on June 3. Her cult transformed her into a patroness for various groups. She is recognized as the patron saint of queens, widows, brides, and exiles. Particularly in Normandy, she is invoked as the patron saint of the lame, those who have suffered a tragic death, and women tormented by ill-tempered or abusive husbands. Her significance is also tied to specific locations, notably Les Andelys, where her miraculous fountain is believed to have healing powers.

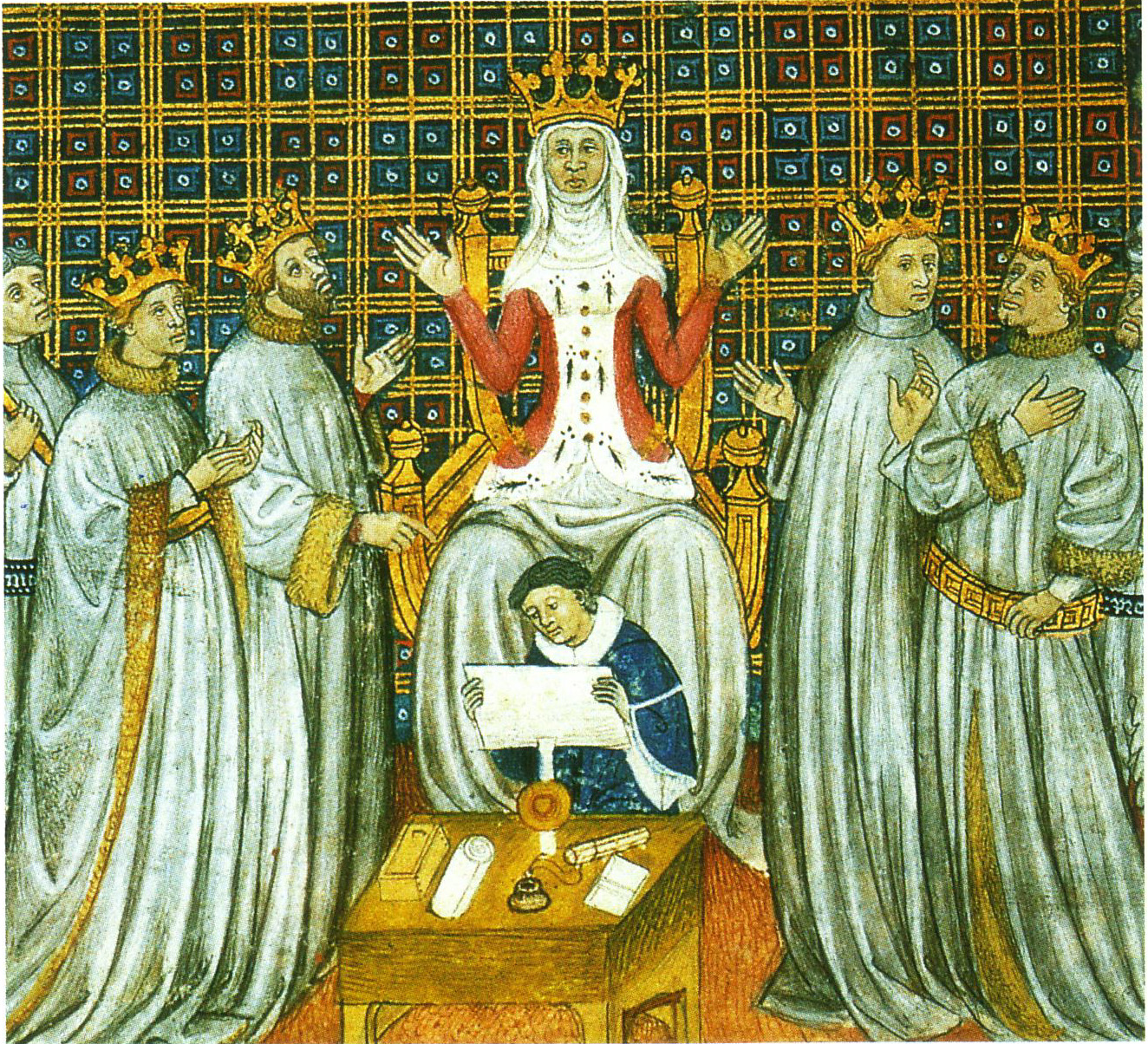

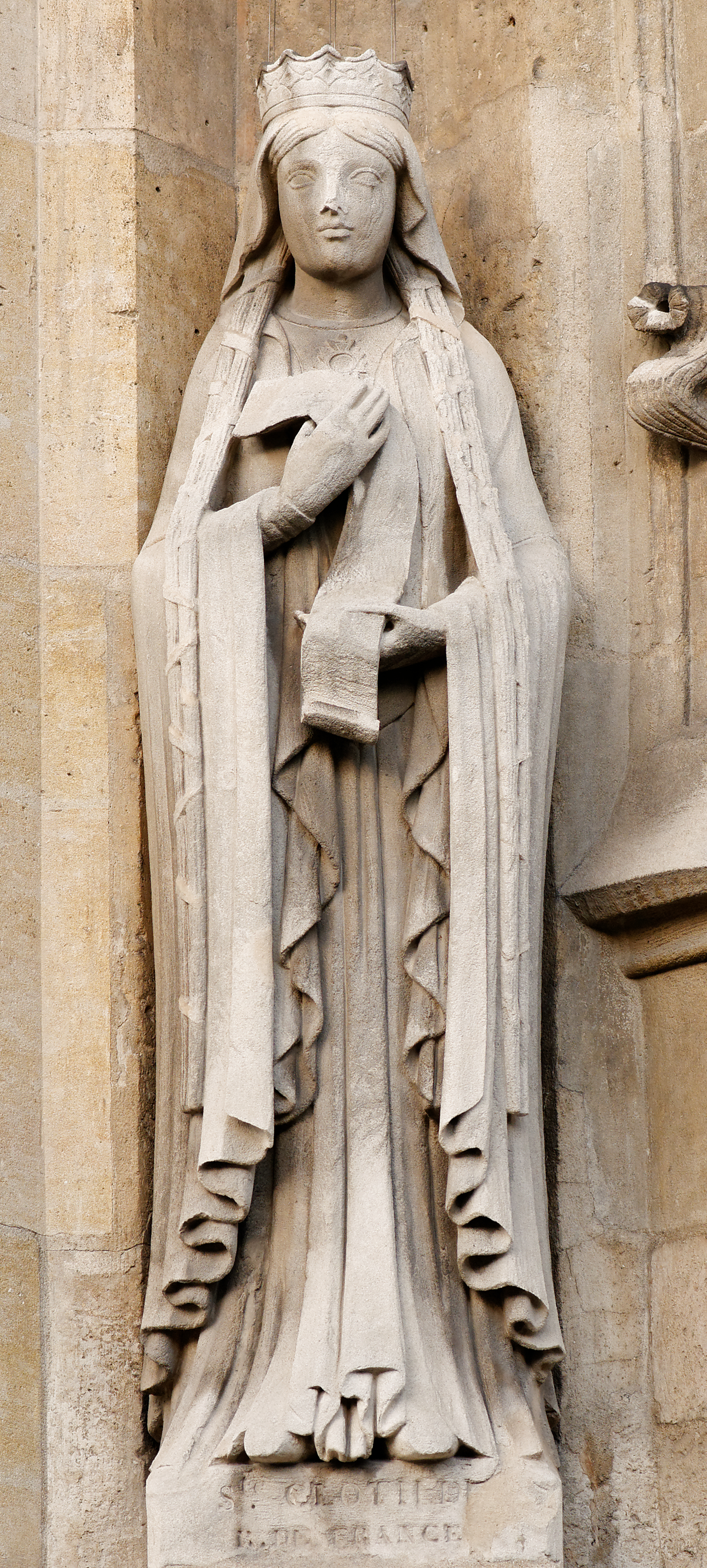

6.2. Artistic Depictions

Saint Clotilde has been a recurring figure in art throughout history, depicted in various forms and contexts. She is often portrayed as a praying queen, sometimes with a crown on or beside her, or as a nun. Common artistic themes include her presiding over the baptism of Clovis, highlighting her pivotal role in his conversion, or appearing as a suppliant at Saint Martin of Tours' shrine, reflecting her deep devotion.

Notable artistic representations include a fine 16th-century stained-glass window dedicated to her life in the church at Les Andelys. A painting of Clotilde in the Bedford Missal, possibly by Jan van Eyck, beautifully depicts the granting of the lilies to Clovis. Sculptures of Saint Clotilde can be found in various churches, such as the one in Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois in Paris, and a statue by Eugène Guillaume and Alexandre-Dominique Denuelle. Her relics survived the French Revolution and, as of 1997, were housed at the Church of Saint Louis of France in Paris. In 1857, a grand new church was founded in her honor in Paris, further cementing her enduring veneration.

6.3. Historical Evaluation

Clotilde's historical evaluation underscores her profound impact on early Frankish history and the trajectory of Christianity in Western Europe. Her role in converting Clovis I is consistently highlighted as a monumental achievement, establishing the Franks as a Catholic power and thereby influencing the religious landscape for centuries. Historians note her dedication to her faith and her tireless efforts in establishing churches, monasteries, and charitable foundations, which contributed significantly to the spiritual and social development of the era.

While some historical accounts, particularly those from earlier hagiographers like Gregory of Tours, presented a more vindictive image of Clotilde, later scholarship, notably by historians such as Godefroid Kurth, has questioned these narratives, often viewing them as later embellishments or defaming portrayals inconsistent with her saintly character. These re-evaluations have largely vindicated her from charges of inciting violence for revenge, emphasizing her piety and devotion instead. Despite the internal family strife and political turmoil she endured, Clotilde is widely assessed as a figure of immense religious and cultural significance, celebrated for her unwavering faith, charitable works, and enduring legacy as the "saintly ancestor of the French kings."