1. Early Life and Recognition

The Panchen Lama incarnation line began in the seventeenth century after the 5th Dalai Lama gave Chokyi Gyeltsen the title, declaring him an emanation of Amitābha Buddha. Officially, he became the first Panchen Lama in the lineage, while also being the sixteenth abbot of Tashilhunpo Monastery.

The 10th Panchen Lama was born as Gonpo Tseten on 19 February 1938, in Bido, located in today's Xunhua Salar Autonomous County of Qinghai, a region historically known as Amdo. His father was also named Gonpo Tseten, and his mother was Sonam Drolma. Following the death of the Ninth Panchen Lama in 1937, two simultaneous searches for his reincarnation were initiated, leading to the identification of two different boys as potential successors. The government in Lhasa favored a boy from Xikang, while the Ninth Panchen Lama's khenpos (senior monastic officials) and associates chose Gonpo Tseten.

The Republic of China (ROC) government, then embroiled in the Chinese Civil War, officially declared its support for Gonpo Tseten on 3 June 1949.

2. Enthronement and Early Political Activities

On 11 June 1949, at twelve years of age according to the Tibetan counting system, Gonpo Tseten was formally enthroned at the significant Gelugpa monastery in Amdo, Kumbum Jampa Ling monastery, where he was given the name Lobsang Trinley Lhündrub Chökyi Gyaltsen. The ceremony was attended by prominent ROC officials, including Guan Jiyu, the head of the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission, and Ma Bufang, the Kuomintang (KMT) Governor of Qinghai.

During the ongoing Chinese Civil War, the ROC government sought to leverage Choekyi Gyaltsen to establish a broad anti-Communist base in Southwest China. The KMT formulated a plan envisioning three Tibetan Khampa divisions, with the assistance of the Panchen Lama, to oppose the Communists. When the Lhasa government denied Choekyi Gyaltsen control over the territory traditionally governed by the Panchen Lamas, he reportedly sought assistance from Ma Bufang in September 1949 to lead an army against Tibet. As the Communist victory became imminent, Ma Bufang attempted to persuade the Panchen Lama to accompany the KMT government to Taiwan. However, the Panchen Lama instead declared his support for the Communist People's Republic of China. This decision was influenced by the unstable regency of the Dalai Lama, which had experienced a civil war in 1947, a situation the KMT had exploited to expand its influence in Lhasa.

Following their meeting in 1952, the 14th Dalai Lama formally recognized the Panchen Lama Choekyi Gyaltsen.

3. Relationship with the People's Republic of China

The Panchen Lama's relationship with the People's Republic of China was complex and evolved over time. Initially, he publicly supported China's claim of sovereignty over Tibet and endorsed its reform policies for the region. Radio Beijing even broadcast his call for Tibet to be "liberated" into China, which exerted pressure on the Lhasa government to negotiate with the PRC. He supported the idea of social reform and political stability in Tibet through its integration with the PRC.

In 1951, the Panchen Lama conducted a Kalachakra initiation at Kumbum Monastery. That same year, he was invited to Beijing as the Tibetan delegation signed the 17-Point Agreement, which then telegrammed the Dalai Lama to implement the accord.

3.1. Political Positions and Activities

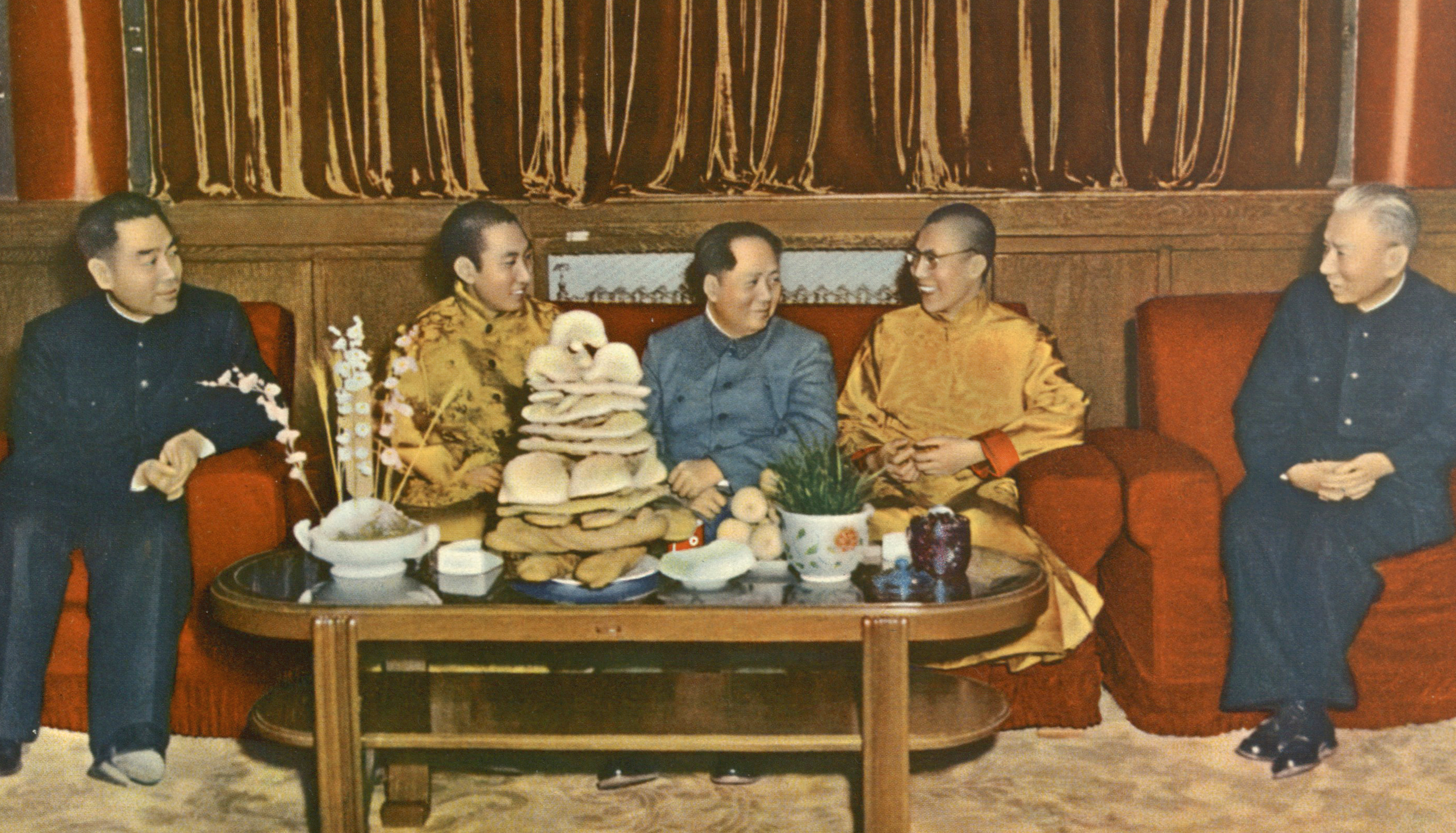

In September 1954, the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama traveled together to Beijing to attend the first session of the first National People's Congress, where they met Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders. The Panchen Lama was subsequently elected a member of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. In December 1954, he became the deputy chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. In 1956, he undertook a pilgrimage to India alongside the Dalai Lama.

When the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959 following the 1959 Tibetan uprising, the Panchen Lama publicly supported the Chinese government. The Chinese authorities then brought him to Lhasa and appointed him chairman of the Preparatory Committee for the Tibet Autonomous Region. Despite this prominent role, he was often viewed as a "puppet" by the Tibetan exile community due to his perceived alignment with the Chinese Communist Party.

3.2. Stance on Tibetan Policies

The Panchen Lama publicly endorsed the Chinese government's policies in Tibet and supported the implementation of various reform measures. He advocated for social and political stability in Tibet through its integration with the People's Republic of China. However, his position was fraught with internal conflicts and nuances, as he grappled with the practical implications and human costs of these policies on the Tibetan people.

4. Criticism of Chinese Policies and Persecution

Despite his initial cooperation with the Chinese government and his high-ranking political positions, the Panchen Lama's stance gradually shifted as he witnessed the realities of Chinese rule in Tibet. He became increasingly critical of the oppressive policies and actions of the People's Republic of China, leading to severe persecution.

4.1. The 70,000 Character Petition

After an extensive tour through Tibet in 1962, the Panchen Lama compiled a detailed document addressed to Premier Zhou Enlai, which became known as the "70,000 Character Petition." This petition served as a scathing denunciation of the abusive policies and actions of the People's Republic of China in Tibet. It is considered the "most detailed and informed attack on China's policies in Tibet that would ever be written."

The petition comprised eight main points, critically examining various aspects of Chinese rule:

- Political Oppression**: The Panchen Lama criticized the excessive retaliatory punishments meted out by the Chinese government following the 1959 Tibetan uprising. He reported mass arrests, with over 10,000 people detained in each region, regardless of their innocence or guilt, stating, "This is not in accordance with any legal system existing anywhere in the world." He also highlighted that in some areas, the majority of men were imprisoned, leaving women, the elderly, and children to shoulder most of the work. The petition further detailed that relatives were executed under collective responsibility, and political prisoners were intentionally subjected to harsh conditions, leading to an extremely high rate of unnatural deaths.

- Famine**: The petition exposed the devastating impact of the Great Leap Forward in Tibet, where widespread starvation led to high mortality rates, with some areas being "wiped out." The Panchen Lama noted that Tibet had never experienced such food shortages, even during its "dark and barbaric feudal society," especially after the spread of Buddhism. He described the extreme poverty, with many people on the verge of starvation or dying from illness due to weakened resistance. He reported that Tibetans were forced to eat in public canteens, receiving only 6.3 oz (180 g) of wheat mixed with grass, leaves, and tree bark daily, which was insufficient to sustain life. He wrote, "The people could not even imagine such terrible hunger in their dreams." The famine, particularly in the Kham region, continued until 1965.

- Ethnic Extermination**: The Panchen Lama expressed deep concern about the potential disappearance of the Tibetan ethnicity. He warned that if a people's language, clothing, and customs were removed, they would vanish and transform into another ethnicity, questioning how anyone could guarantee that Tibetans would not change into another people.

- Religious Persecution**: The petition documented the widespread destruction of Buddhist monasteries, even before the Cultural Revolution. The Panchen Lama reported that out of 2,500 monasteries, only 70 remained, and 93 percent of monks and nuns had been expelled. He accused Communist Party cadres of using a small number of individuals to denounce religion, fabricating the impression that this was the opinion of the Tibetan masses, and concluding that the time had come to eradicate religion. He lamented that the Buddha's teachings, which had flourished throughout Tibet, were now being erased before their eyes, a situation he believed 90 percent of Tibetans, including himself, could not endure.

The Panchen Lama met with Zhou Enlai to discuss his petition. While the initial reaction was reportedly positive, by October 1962, PRC authorities criticized the petition. Mao Zedong himself condemned it as "... a poisoned arrow shot at the Party by reactionary feudal overlords." For decades, the contents of this report remained highly classified, known only to the highest levels of Chinese leadership, until a copy surfaced in 1996. In January 1998, an English translation by Tibet expert Robert Barnett, titled A Poisoned Arrow: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama, was published.

4.2. Arrest, Imprisonment, and Struggle Sessions

The Panchen Lama's outspoken criticisms led to severe repercussions. In 1964, during the annual Great Prayer Festival (Monlam Chemo) in Lhasa, he was ordered by the Chinese Communist Party to publicly denounce the Dalai Lama. Instead, he courageously declared to the assembled crowd, "His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the true leader of Tibet, and His Holiness will surely return to Tibet. Long live His Holiness the Dalai Lama!" This act of defiance infuriated the Communist Party.

Later in 1964, he was subjected to public humiliation at Politburo meetings, dismissed from all his positions of authority, and declared an "enemy of the Tibetan people." His personal dream journal was even confiscated and used against him. At the age of 26, he was then imprisoned. His situation worsened significantly with the onset of the Cultural Revolution. He was held in Qincheng Prison from 1968 until 25 February 1978, enduring ten years of incarceration. Even after his release from prison in October 1977, he remained under house arrest in Beijing until 1982.

5. Later Life and Rehabilitation

Following his release and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Panchen Lama entered a new phase of his life, marked by political rehabilitation and personal changes.

5.1. Release and Political Rehabilitation

After his release from prison in October 1977 and subsequent house arrest, the Panchen Lama was gradually politically rehabilitated by the Chinese government. By 1982, he was fully rehabilitated and resumed public life and political activities. He was appointed Vice Chairman of the National People's Congress and other political posts, signifying a restoration of his official standing.

5.2. Marriage and Family

In 1978, after renouncing his vows as an ordained monk, the Panchen Lama began traveling around China, seeking a wife to start a family. He eventually began courting Li Jie, a Han Chinese woman and the uterine granddaughter of Dong Qiwu, a general in the People's Liberation Army (PLA) who had commanded an army in the Korean War. At the time, the Panchen Lama had no personal wealth and was still blacklisted by the Communist Party. However, the wife of Deng Xiaoping and the widow of Zhou Enlai recognized the symbolic significance of a marriage between a Tibetan Lama and a Han woman. They personally intervened to facilitate the union, and the couple was wed in a large ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in 1979.

This marriage, a departure from the traditional monastic vows of a Gelug school monk, caused considerable shock within the Tibetan community. While some speculate that the marriage was coerced by the Chinese Communist Party to undermine the Panchen Lama's authority after he refused to remain a mere puppet, others suggest it was his own desire, perhaps a response to the loneliness endured during his prolonged imprisonment.

In 1983, Li Jie gave birth to their daughter, named Yabshi Pan Rinzinwangmo (ཡབ་གཞིས་པན་རིག་འཛིན་དབང་མོ་yab gzhis pan rig 'dzin dbang moTibetan). Popularly known as the "Princess of Tibet," she holds significant importance in both Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan-Chinese politics, as she is the only known offspring in the over 620-year history of either the Panchen Lama or Dalai Lama reincarnation lineages. Regarding her father's death, Rinzinwangmo reportedly attributed it to his generally poor health, morbid obesity, and chronic sleep deprivation. Following the 10th Panchen Lama's death, a six-year dispute arose over his assets, amounting to 20.00 M USD, between his wife and daughter and Tashilhunpo Monastery.

5.3. Return to Tibet and Public Activities

After his rehabilitation, the Panchen Lama made several significant journeys to Tibet from Beijing, beginning in 1980. These visits allowed him to reconnect with the Tibetan people and engage in important religious and cultural activities.

In 1980, while touring eastern Tibet, the Panchen Lama visited the renowned Nyingma school master Khenchen Jigme Phuntsok at Larung Gar. In 1987, the Panchen Lama met Khenchen Jigme Phuntsok again in Beijing, where he bestowed the teaching of the "Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva." He also blessed and endorsed Larung Gar, formally conferring its name as Serta Larung Ngarik Nangten Lobling (གསེར་རྟ་བླ་རུང་ལྔ་རིག་ནང་བསྟན་བློ་བསྒྲུབ་གླིང་gser rta bla rung lnga rig nang bstan blob glingTibetan), commonly translated as Serta Larung Five Science Buddhist Academy.

In 1988, at the Panchen Lama's invitation, Khenchen Jigme Phuntsok joined him for a consecration ritual in central Tibet. This became a monumental pilgrimage to various sacred Buddhist sites across Tibet, including the Potala Palace, the Norbulingka, Nechung Monastery, Sakya Monastery, Tashilhunpo Monastery, and Samye Monastery. During these journeys, thousands of Tibetans would walk for days to line up and receive a blessing from him, demonstrating his enduring spiritual authority and the deep reverence he commanded among the populace.

Also in 1987, the Panchen Lama established a business called the Tibet Gang-gyen Development Corporation. This initiative was envisioned for the future of Tibet, aiming to empower Tibetans to take the lead in their own modernization and development. Plans to rebuild sacred Buddhist sites that had been destroyed in Tibet during and after 1959 were included in this endeavor. Gyara Tsering Samdrup, who worked with this corporation, was later arrested in May 1995 following the recognition of the 11th Panchen Lama Gedhun Choekyi Nyima.

Early in 1989, the 10th Panchen Lama returned to Tibet once more to rebury recovered bones from the graves of previous Panchen Lamas. These graves had been desecrated and destroyed at Tashilhunpo Monastery in 1959 by the Red Guards. The recovered bones were consecrated and placed in a specially built chorten (stupa) as a receptacle.

On 23 January 1989, the Panchen Lama delivered a powerful and candid speech in Tibet. In it, he stated: "Since liberation, there has certainly been development, but the price paid for this development has been greater than the gains." He openly criticized the excesses of the Cultural Revolution in Tibet and, while praising the reform and opening up policies of the 1980s, his overall message highlighted the immense suffering and destruction inflicted upon Tibet under Chinese rule.

6. Death

The 10th Panchen Lama died five days after his critical speech, on 28 January 1989, in Shigatse, at the age of 50. His death sparked widespread suspicion and various theories among Tibetans and international observers.

6.1. Circumstances and Suspicions

The official cause of death was stated to be a heart attack. However, many Tibetans and others harbored strong suspicions of foul play, believing that his death was not natural and that he may have been poisoned by his own medical staff. This belief was shared by the 14th Dalai Lama.

Several theories and legends circulated among Tibetans regarding the Panchen Lama's death. One story claimed he foresaw his own death, conveying a message to his wife during their last meeting. Another recounted a rainbow appearing in the sky shortly before his passing. The suspicions of poisoning were fueled by the critical remarks the Panchen Lama had made on 23 January to high-ranking officials, which were subsequently published in the People's Daily and the China Daily.

In 2011, Chinese dissident Yuan Hongbing publicly declared that Hu Jintao, who was then the Communist Party Secretary of Tibet and Political Commissar of the PLA's Tibet units, had masterminded the death of the 10th Panchen Lama.

In August 1993, his body was moved to Tashilhunpo Monastery. It was initially placed in a sandalwood bier, then transferred to a specially made safety cabinet, and finally enshrined within the Precious Bottle in the stupa of the monastery, where it remains preserved. The state-run People's Daily reported that the Buddhist Association of China invited the Dalai Lama to attend the Panchen Lama's funeral, offering him an opportunity to connect with Tibet's religious communities. However, the Dalai Lama was unable to attend the funeral.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

The 10th Panchen Lama's life and actions present a complex and often contradictory legacy, reflecting the immense pressures faced by Tibetan religious leaders under Chinese rule. He remains a figure of profound significance in Tibetan Buddhism and society.

7.1. Evaluation within Tibet

Within Tibet, the Panchen Lama is largely perceived as a courageous leader who, despite being forced into a difficult political position, ultimately championed the rights and welfare of his people. His initial cooperation with the Chinese government was often seen as a pragmatic attempt to navigate a perilous political landscape and maintain a presence within Tibet. However, his later outspoken criticisms, particularly the "70,000 Character Petition" and his defiant speech at Monlam Chemo, solidified his image as a defender of Tibetan identity, culture, and human rights.

Tibetans widely respected his efforts to preserve and restore Buddhist institutions, especially the Tashilhunpo Monastery, which had been devastated during the Cultural Revolution. His personal suffering-including long years of imprisonment and public humiliation-further endeared him to the Tibetan populace, who saw him as a martyr for their cause. His sincerity and resilience transformed the perception of him from a potential "puppet" to a symbol of resistance and hope, bridging the gap between Tibetan aspirations and the realities of Chinese governance. His final speech, acknowledging the immense "price paid" for development, resonated deeply with the Tibetan experience of suffering under Chinese rule.

7.2. Critical Perspectives

Critical perspectives on the Panchen Lama's life often focus on the compromises he made and his political alignment with the Chinese Communist Party, especially in his early years. Some critics, particularly within the Tibetan exile community, initially viewed his public support for Chinese policies and his acceptance of high-ranking political posts as a betrayal or a sign of collaboration. His marriage to a Han Chinese woman and the renunciation of his monastic vows were also points of contention for some, seen as a departure from traditional Buddhist principles.

However, a more nuanced assessment acknowledges the impossible situation he faced. Trapped between the demands of the Chinese state and the loyalty to his people and faith, his actions can be interpreted as a strategic attempt to protect Tibetan Buddhism and culture from within the system. His eventual and increasingly vocal criticisms, which led to his persecution, demonstrate his ultimate commitment to the Tibetan cause, even at great personal risk. These later actions often mitigate earlier criticisms, portraying him as a tragic figure who, despite difficult choices, ultimately stood firm against oppression. His life serves as a powerful illustration of the profound challenges faced by religious and cultural leaders in regions under authoritarian control.