1. Overview

Atlas (ἌτλαςÁtlāsGreek, Ancient) is a prominent Titan in Greek mythology, primarily known for his eternal punishment of holding up the heavens or sky. He is often depicted as a colossal, muscular figure bearing the weight of the celestial spheres, though a common misconception portrays him holding the terrestrial globe. Atlas is the son of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Asia or Clymene. He is also known as the brother of Prometheus, Epimetheus, and Menoetius. Some ancient accounts, notably by Hyginus, suggest a more primordial origin, identifying his parents as Aether and Gaia.

His punishment, imposed by Zeus after the Titanomachy-the war between the Titans and the Olympian gods-condemned him to stand at the extreme western edge of the Earth, perpetually bearing the heavens on his shoulders. This enduring burden has made Atlas a symbol of great strength, resilience, and responsibility.

Beyond his role in supporting the sky, Atlas features in the myths of two significant Greek heroes: Heracles and Perseus. He is also historically associated with the Atlas Mountains in Northwest Africa, where he was sometimes regarded as the first King of Mauretania (modern-day Morocco and western Algeria). In this capacity, he was credited with advanced knowledge in philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy, even being attributed with the invention of the first celestial spheres and astronomy itself. The name "Atlas" has significantly influenced cartography, being used for collections of maps since the 16th century, and is also the origin of the names "Atlantic Ocean" and the legendary island of "Atlantis".

2. Etymology

The etymology of the name Atlas is uncertain, with several theories proposed for its origin. The Roman poet Virgil often associated the name with adjectives that clarified its meaning, using durus (meaning "hard" or "enduring"). This suggests that Virgil might have connected Atlas's name to the Greek verb τλῆναι (tlênai), meaning "to endure" or "to uphold." This interpretation aligns with Atlas's mythological role as the bearer of the heavens.

Another proposed origin links the name to the Berber languages, specifically to the word ádrār, which means "mountain." This theory is supported by the fact that the Atlas Mountains, with which the Titan later became strongly identified, are located in a region historically inhabited by Berber peoples. The ancient Greek word Ἄτλας (genitive: Ἄτλαντος) has also been etymologically linked by some historical linguists to the Proto-Indo-European root `*telh₂-`, also meaning 'to uphold, support'.

However, Robert S. P. Beekes, a prominent historical linguist, argued against an Indo-European origin for the name. He suggested that it is more likely of Pre-Greek origin, noting that many words from this substratum in Greek often end in the suffix -ant, a pattern observed in Atlas's name. The Japanese translation of his name, アトラースAtlāsJapanese, is also sometimes shortened to "Atlas" in Japanese and is described as meaning "supporter," "endurer," or "defier" in Old Indo-European languages, reinforcing the enduring and defiant aspect of his mythological role.

3. Family

Atlas's familial relationships are complex and vary across ancient sources, encompassing a wide array of parents, siblings, and numerous children, primarily daughters.

3.1. Parents and Siblings

Atlas's parentage is most commonly attributed to the Titan Iapetus and an Oceanid, a sea nymph daughter of Oceanus and Tethys. According to Hesiod's Theogony, his mother was Clymene, while Apollodorus identifies his mother as Asia. These Oceanids are distinct figures, and some scholars suggest Asia became preferred to avoid confusion with other nymphs named Clymene.

He had three well-known brothers: the cunning Prometheus, the impulsive Epimetheus, and the proud Menoetius. All four brothers were sons of Iapetus, tying them directly to the generation of Titans who preceded the Olympian gods.

In some accounts, particularly that of Hyginus in his Fabulae, an older version of Atlas is presented as the son of Aether (the primordial god of the upper air and light) and Gaia (the primordial goddess of the Earth). This alternative parentage emphasizes Atlas's deep connection to the most fundamental elements of the cosmos, highlighting his ancient and foundational nature. According to the works of Eusebius and Diodorus Siculus, this Atlantean account posits Atlas's grandfather as Elium, "King of Phoenicia," who lived in Byblos, and his wife Beruth. Atlas was raised by his sister, Basilia.

3.2. Children

Atlas was the father of numerous children, predominantly daughters, through unions with various goddesses and nymphs. These offspring often played significant roles in other Greek myths.

One prominent group of his daughters were the Hesperides, the nymphs who guarded the tree of golden apples in Hera's garden. They were born from Atlas's union with Hesperis. Different sources attribute varying numbers of Hesperides, but they are consistently linked to Atlas and his western domain.

By Pleione (or in some accounts, Aethra), Atlas fathered several groups of celestial nymphs and a son:

- The Hyades: Five daughters who, after the death of their brother Hyas, were transformed into a star cluster associated with rain.

- Hyas: Atlas's only known son from this union, whose premature death led to his sisters' grief and transformation.

- The Pleiades: Seven beautiful nymph sisters who were transformed into the star cluster known as the Pleiades. Their names were Maia, Taygete, Sterope, Merope, Celaeno, Alcyone, and Electra. Maia, the eldest, famously became the mother of Hermes by Zeus.

Additionally, Atlas had other daughters whose mothers are often unspecified in mythological texts:

- Calypso: A nymph who famously detained Odysseus on her island of Ogygia for several years. Some accounts, such as those found in Japanese sources, state her mother was Tethys, an Oceanid.

- Dione: While often associated with Zeus as the mother of Aphrodite in some traditions, she is also listed as a daughter of Atlas.

- Maera: A nymph connected to the realm of the afterlife in certain traditions.

4. Mythology

Atlas's role in Greek mythology is deeply intertwined with the cosmic order, divine punishment, and encounters with renowned heroes, reflecting themes of enduring burden and the clash between generations of gods.

4.1. The Titanomachy and Punishment

Atlas played a significant role in the Titanomachy, the epic war between the elder generation of gods, the Titans, and the younger Olympian gods led by Zeus. Atlas, alongside his brother Menoetius, sided with the Titans against the Olympians. When the Titans were ultimately defeated after a fierce and tumultuous conflict, many of them, including Menoetius, were imprisoned in the deep abyss of Tartarus. However, Zeus decreed a unique and eternal punishment for Atlas. Instead of being confined to Tartarus, Atlas was condemned to stand at the extreme western edge of the Earth, specifically at the ends of the earth near the realm of the Hesperides, and eternally bear the weight of the heavens or sky on his shoulders. This arduous task was a constant, agonizing burden, marking him as "Atlas Telamon," meaning "enduring Atlas." He also became associated with Coeus, the embodiment of the celestial axis around which the heavens revolve, reflecting his central role in maintaining the cosmic order.

A common modern misconception, particularly in popular culture, is that Atlas was forced to hold the Earth or the terrestrial globe on his shoulders. However, classical art, including the famous Farnese Atlas, consistently depicts him holding the celestial spheres (the cosmos), not the terrestrial globe. This distinction emphasizes his cosmic burden rather than a physical one on Earth. The visual representation of a solid marble globe in artworks like the Farnese Atlas may have contributed to this conflation, which was further reinforced in the 16th century by the emerging use of the term "atlas" to describe collections of terrestrial maps.

4.2. Encounters with Heroes

Atlas's solitary existence at the edge of the world was interrupted by significant encounters with two of Greece's most famous heroes, Perseus and Heracles, both of whom were sons of Zeus.

4.2.1. Perseus

The Greek poet Polyidus, around 398 BC, recounted a tale where Atlas, then a shepherd, encountered Perseus and was transformed into stone by the hero. A more detailed and widely known account comes from Ovid's Metamorphoses, which combines this incident with elements of the Heracles myth. In Ovid's narrative, Atlas is not a shepherd but a formidable king. Perseus, claiming to be a son of Zeus, arrived in Atlas's kingdom seeking shelter. Atlas, however, refused hospitality. He harbored fear of an ancient prophecy that warned of a son of Zeus who would one day steal the golden apples from his orchard. This prophecy, though misinterpreted by Atlas, actually referred to Heracles, another son of Zeus and Perseus's great-grandson.

In his rage or to escape the perpetual burden, Atlas either requested Perseus to turn him to stone to end his suffering, or Perseus, angered by the refusal of hospitality, used the severed head of Medusa, which he carried, to petrify Atlas. The sight of Medusa's Gorgon head instantly turned Atlas into a massive mountain range. According to Ovid, Atlas's head became the towering peak of the mountain, his shoulders formed broad ridges, and his hair transformed into the vast forests that covered them. This myth provides an etiological explanation for the formation of the Atlas Mountains in North Africa.

4.2.2. Heracles

One of the Twelve Labours assigned to the hero Heracles by King Eurystheus was to obtain some of the precious golden apples from Hera's garden. This garden was tended by Atlas's daughters, the Hesperides (also known as the Atlantides), and fiercely guarded by the dragon Ladon. Heracles, seeking assistance, traveled to Atlas at the western edge of the world.

Upon meeting Atlas, Heracles proposed a deal: he would temporarily hold up the heavens, relieving Atlas of his crushing burden, if Atlas would fetch the golden apples from his daughters' garden. Atlas, eager for a moment of respite from his eternal task, agreed to the proposition. He laid down the sky, and Heracles, with a padded cloak, took on the immense weight. Atlas then went to collect the apples.

However, upon his return with the golden apples, Atlas, realizing the temporary freedom from his burden, attempted to trick Heracles. He offered to personally deliver the apples to Mycenae, implying that Heracles should continue holding the sky permanently. Heracles, suspecting Atlas's deceitful intent, pretended to agree. He cunningly asked Atlas to take the sky back for just a few moments so he could rearrange his cloak to provide better padding on his shoulders. Atlas, falling for the ruse, set down the apples and resumed his cosmic burden. At that precise moment, Heracles quickly grabbed the apples and, without hesitation, departed for Mycenae, leaving Atlas to his eternal punishment once more.

In some alternative versions of the myth, Heracles does not trick Atlas. Instead, after obtaining the apples, Heracles constructs the two great Pillars of Hercules (traditionally identified with the Strait of Gibraltar) to hold the sky away from the earth, thereby liberating Atlas from his burden, much as he had previously freed Prometheus.

4.3. Other Figures Named Atlas

The name Atlas appears in various other mythological or legendary contexts, referring to figures distinct from the Titan condemned to bear the sky.

4.3.1. King of Atlantis

According to Plato's dialogues, particularly Critias, the first king of the legendary island of Atlantis was also named Atlas. This Atlas, however, was a son of the sea god Poseidon and a mortal woman named Cleito, making him a different lineage from the Titan. Plato describes how Poseidon fell in love with Cleito and built a magnificent city on a hill where she lived, raising five pairs of twin sons, with Atlas being the eldest. He inherited the largest and central part of Atlantis, and the surrounding ocean was named after him.

In other ancient accounts, such as those found in the works of Eusebius and Diodorus Siculus, another Atlantean narrative describes an Atlas whose father was Uranus (the primordial sky god) and his mother was Gaia (the Earth goddess). This version aligns him more closely with the primordial deities, though his story diverges from that of the Titan Atlas. This Atlas was said to have been raised by his sister, Basilia, and his grandfather was Elium, who was described as the "King of Phoenicia" and lived in Byblos. These accounts from Eusebius are noted to have been derived from ancient Phoenician texts, potentially predating the Trojan War.

4.3.2. King of Mauretania

Another legendary figure named Atlas was a king of Mauretania, an ancient region in Northwest Africa that roughly corresponds to modern-day Morocco and western Algeria. This King Atlas was celebrated for his profound wisdom in philosophy, mathematics, and especially astronomy. He was often credited with inventing the first celestial spheres and, in some texts, even the entire science of astronomy itself. The myth held that the heavens were supported on his shoulders metaphorically due to his discovery and description of the sphere.

Over time, Atlas became strongly associated with Northwest Africa. This connection was partly due to his mythological links with the Hesperides, who were said to reside beyond the Ocean in the extreme west of the world since Hesiod's Theogony. The Gorgons were also said to live in this region. Diodorus Siculus and Palaephatus mentioned the Gorgons living in the Gorgades, islands in the Aethiopian Sea, which some modern arguments suggest may correspond to the Cape Verde islands. By the time of the Roman Empire, the tradition of associating Atlas's home with the chain of mountains known as the Atlas Mountains, located near Mauretania and Numidia, was firmly established. The 16th-century cartographer Gerardus Mercator notably dedicated his groundbreaking collection of maps, which he titled "Atlas," to this learned King of Mauretania.

4.3.3. In Etruscan Mythology

In Etruscan mythology, a figure identified as 'Aril' is associated with Atlas. This name is inscribed on two 5th-century BC Etruscan bronze artifacts: a mirror found in Vulci and a ring from an unknown site. Both of these objects depict an encounter between Aril and Hercle, the Etruscan equivalent of Heracles, who is identified by inscription. These depictions are rare instances where a figure from Greek mythology was incorporated into Etruscan mythology, but without adopting the Greek name directly. The Etruscan name 'Aril' is considered etymologically independent of 'Atlas'. Scholars have investigated its possible meaning, suggesting it might relate to a Phoenician etymon signifying "guarantor in a commercial transaction" or "mediator."

5. Cultural Significance

The myth of Atlas has exerted a profound and enduring influence across various cultural domains, extending from cartography and literature to psychology and popular culture, often serving as a powerful metaphor for bearing immense weight or responsibility.

5.1. In Cartography

The most enduring cultural legacy of Atlas is undoubtedly in the field of cartography. The term "atlas" to describe a collection of maps has been in use since the 16th century. The first publisher to feature a depiction of the Titan Atlas on the engraved title page of his map collections was the Italian print-seller Antonio Lafreri in 1572. His work, Tavole Moderne di Geografia de la Maggior parte do Mondo di Diversi Autori, although not bearing the title "Atlas," visually associated the Titan with geographical compilations.

However, it was the renowned Flemish geographer Gerardus Mercator who popularized the term. In 1585, he published his seminal work, Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati, which is widely recognized as the first collection of maps explicitly titled "Atlas." Mercator chose this name not primarily to honor the mythological Titan bearing the heavens, but rather to honor the legendary King of Mauretania named Atlas, who was renowned as a learned philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer. Mercator's initial 1595 edition of the Atlas indeed depicted this scholarly King Atlas on its cover. It was only from the 1636 edition onwards that the cover art shifted to feature the mythological Titan Atlas, holding the celestial spheres, solidifying the association of the name "atlas" with maps in popular imagination.

The influence of Atlas extends beyond just map collections. The "Atlantic Ocean" derives its name from "Sea of Atlas," and the legendary island of "Atlantis", as mentioned in Plato's Timaeus dialogue, comes from "Atlantis nesos" (Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσοςAtlantis nesos, literally "Atlas's Island"Greek, Ancient), literally meaning "Atlas's Island," with some myths even referring to the Titan as a king of Atlantis.

5.2. Modern Interpretations and References

The myth of Atlas continues to resonate in modern contexts, serving as a powerful metaphor for burdens, responsibility, and the foundations of knowledge.

In **psychology**, the term "Atlas personality" is used to describe individuals whose childhoods were characterized by excessive responsibilities, often taking on roles typically handled by adults. Such individuals metaphorically carry the weight of their family or circumstances on their shoulders.

In **literature**, the Atlas myth is famously referenced in Ayn Rand's 1957 political dystopian novel, Atlas Shrugged. The novel's title and central metaphor compare the capitalist and intellectual classes to "modern Atlases" who bear the weight of the world's economy and innovation, implying that if they were to "shrug," the world would collapse. This references the popular misconception of Atlas holding up the entire world.

The name "Atlas" has also been adopted in **space technology**. The Atlas rockets were a series of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) developed by the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s. These powerful rockets were later adapted for space exploration, serving as launchers for numerous satellites and even for manned missions during the Mercury program, signifying their role in literally launching things into the heavens.

Beyond these, the name appears in various other fields. In **zoology**, the Atlas beetle (Chalcosoma atlas), a genus of rhinoceros beetles, is named after the Titan due to its impressive size and strength. The name has also been used for **vehicle models**, such as those produced by Volkswagen and Nissan, evoking strength and reliability. In **music**, the German composer Franz Schubert included a song titled "Der Atlas" ("The Atlas") in his posthumously published song cycle Schwanengesang (Swan Song), based on a poem by Heinrich Heine. The poem powerfully depicts the immense, crushing burden of the world that the speaker feels, echoing Atlas's predicament.

6. Genealogy

Atlas's lineage and offspring form a complex web within Greek mythology. He is primarily recognized as the son of the Titan Iapetus. His mother is identified either as Clymene (an Oceanid and daughter of Oceanus and Tethys) by Hesiod, or as Asia (another Oceanid) by Apollodorus. Atlas had three well-known brothers: Prometheus, Epimetheus, and Menoetius. Some ancient sources, such as Hyginus, provide an alternative, more primordial parentage for an older Atlas, identifying him as the son of Aether (the sky god) and Gaia (the Earth goddess).

Atlas fathered numerous children, mostly daughters, through various divine mothers:

- With Hesperis, Atlas was the father of the Hesperides, the nymphs who tended the golden apples.

- With Pleione (or, in some accounts, Aethra), he had several children, including:

- The Hyades, five daughters who were transformed into a star cluster.

- A son, Hyas.

- The Pleiades, seven prominent daughters who became a star cluster: Maia, Taygete, Sterope, Merope, Celaeno, Alcyone, and Electra.

- From unions with other unspecified goddesses, Atlas also fathered:

- Calypso, a nymph famous for detaining Odysseus. Some sources suggest her mother was Tethys.

- Dione, a goddess who appears in various myths.

- Maera, a nymph.

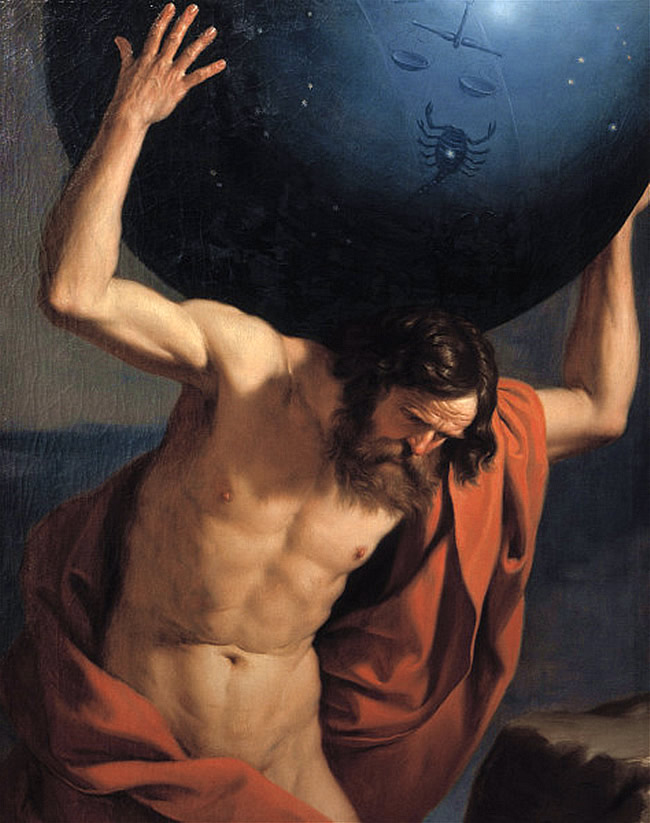

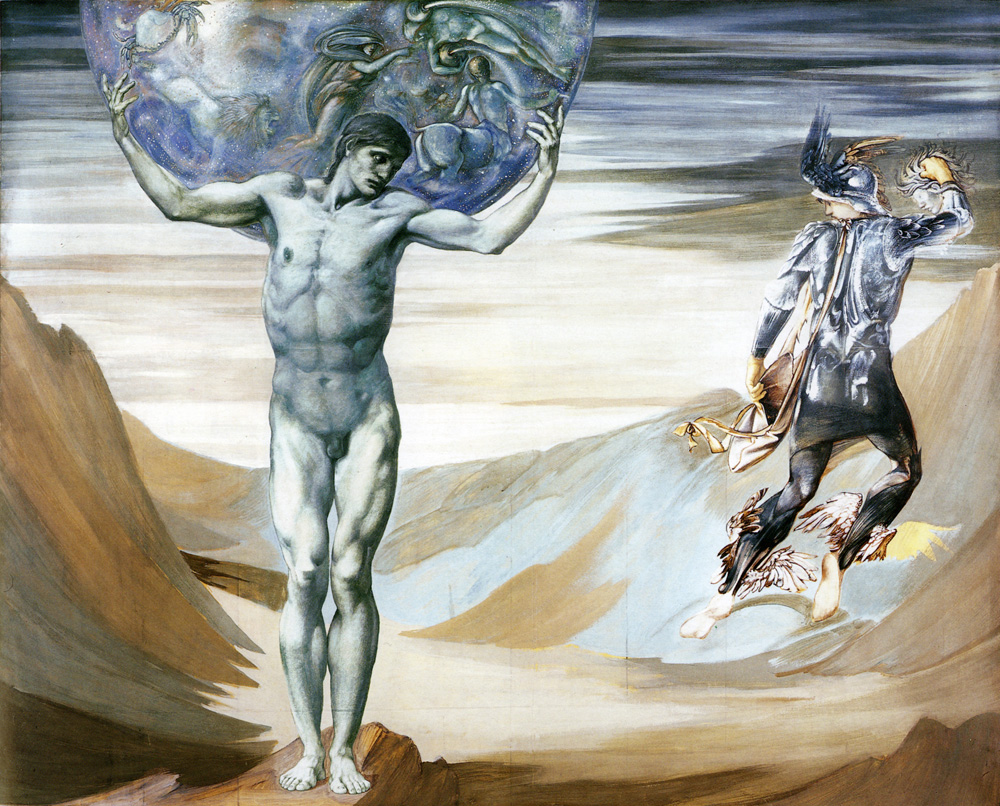

7. Gallery

8. See also

- Atlas (architecture)

- Atlas (statue)

- Atlas beetle

- Atlas Shrugged

- Axis mundi

- Bahamut, a rough analogue from Arabian mythology, and other world-bearing animals

- Farnese Atlas

- Pillars of Hercules

- Schwanengesang, which includes the song "Der Atlas"

- Upelluri