1. Overview

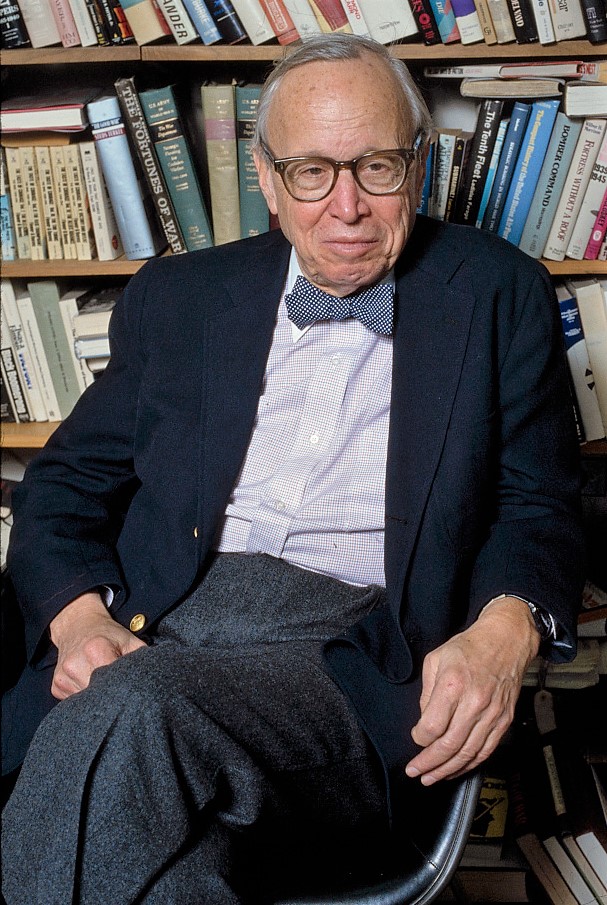

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. (born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger; October 15, 1917 - February 28, 2007) was a prominent American historian, social critic, and public intellectual. The son of influential historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr., Schlesinger Jr. was a specialist in American history, with much of his work exploring the history of 20th-century American liberalism. He extensively focused on leaders such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Robert F. Kennedy. Schlesinger served as a primary speechwriter and advisor for Democratic presidential nominees, including Adlai Stevenson II in 1952 and 1956, and John F. Kennedy in 1960. From 1961 to 1963, he served as Special Assistant to President Kennedy, gaining the moniker "court historian." He authored a detailed account of the Kennedy administration, A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, which earned him the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography in 1966.

In 1968, Schlesinger actively supported the presidential campaign of Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and later penned the popular biography Robert Kennedy and His Times. He also popularized the term "imperial presidency" during the Nixon administration with his 1973 book, The Imperial Presidency. Throughout his distinguished career, he received numerous accolades, including two Pulitzer Prizes and two National Book Awards, along with the Bancroft Prize and a special Four Freedoms Award in 2003.

2. Early Life and Education

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.'s early life was shaped by a family steeped in historical scholarship, which significantly influenced his future academic and intellectual pursuits. His education at prestigious institutions provided a rigorous foundation for his later career as a historian and public figure.

2.1. Early Life and Family

Schlesinger was born Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger on October 15, 1917, in Columbus, Ohio. His parents were Elizabeth Harriet Bancroft and Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. (1888-1965). His father was an influential social historian who taught at Ohio State University and Harvard University, where he supervised numerous PhD dissertations in American history. Schlesinger Jr. would later adopt his father's middle name, Meier, and use the signature "Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr." from his mid-teens. His paternal grandfather was a Prussian Jew who converted to Protestantism and married an Austrian Catholic. His mother, a Mayflower descendant, had German and New England ancestry and was, according to family tradition, a relative of the historian George Bancroft. Schlesinger himself practiced Unitarianism.

2.2. Education

Schlesinger attended the Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. He then pursued his undergraduate degree at Harvard College, graduating summa cum laude at the age of 20 in 1938. Following his graduation, he spent the 1938-1939 academic year at Peterhouse, Cambridge, as a Henry Fellow. In the fall of 1939, he was appointed to a three-year Junior Fellowship in the Harvard Society of Fellows. A unique requirement of the Society of Fellows was that members were not allowed to pursue advanced degrees, ensuring they remained "off the standard academic treadmill." Consequently, Schlesinger never earned a doctorate. His fellowship was interrupted by the United States' entry into World War II.

3. World War II Service

Schlesinger contributed to the American war effort during World War II in intelligence and information roles. After failing his military medical examination, he joined the Office of War Information in 1942, serving there until 1943. From 1943 to 1945, he served as an intelligence analyst in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was the precursor to the CIA. His service in the OSS provided him with the time to complete his first Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Age of Jackson, which was published in 1945.

4. Academic Career

Following his wartime service and the publication of his acclaimed first book, Schlesinger embarked on a distinguished academic career, primarily at Harvard University and later at the CUNY Graduate Center. From 1946 to 1954, he served as an Associate Professor at Harvard University, where his father had also taught. He was promoted to a full Professor in 1954, holding that position until 1962. In 1966, he was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. Later that year, he returned to teaching as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center. He taught there until his retirement in 1994, after which he remained an active member of the Graduate Center community as an emeritus professor until his death.

5. Political Activities and Advocacy

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.'s political engagement extended far beyond academia, encompassing the founding of significant organizations, advising presidential campaigns, and serving in the White House. He was a lifelong voice for American liberalism, critically assessing political developments throughout his career.

5.1. Founding of Americans for Democratic Action (ADA)

In 1947, Schlesinger played a pivotal role in the founding of Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), a political organization dedicated to advocating for progressive policies. He co-founded the organization alongside influential figures such as former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Minneapolis Mayor (and future Senator and Vice President) Hubert Humphrey, economist and close friend John Kenneth Galbraith, and Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Schlesinger's commitment to the ADA was further solidified when he served as its national chairman from 1953 to 1954, championing the organization's liberal and democratic ideals.

5.2. Presidential Campaigns

Schlesinger's expertise and commitment to the Democratic Party were sought by multiple presidential candidates. After President Harry S. Truman announced he would not seek re-election in 1952, Schlesinger became a primary speechwriter and ardent supporter for Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson II. He continued in this crucial role for Stevenson's 1956 presidential campaign, working alongside a 30-year-old Robert F. Kennedy. Schlesinger advocated for the nomination of Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy as Stevenson's vice-presidential running mate in 1956, though Kennedy ultimately lost the balloting to Senator Estes Kefauver.

Schlesinger had known John F. Kennedy since their time at Harvard and became increasingly close with Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, during the 1950s. In 1954, when The Boston Post publisher John Fox Jr. planned to label several Harvard figures, including Schlesinger, as "reds", Kennedy intervened on Schlesinger's behalf, an event Schlesinger later recounted in A Thousand Days. During the 1960 presidential campaign, Schlesinger supported Kennedy, which caused some friction with Stevenson loyalists. After Kennedy secured the nomination, Schlesinger assisted the campaign as a speechwriter, speaker, and active member of the ADA. He also authored the book Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference?, in which he praised Kennedy's abilities while criticizing Vice President Richard M. Nixon, stating that Nixon had "no ideas, only methods.... He cares about winning." Schlesinger continued his involvement in presidential politics, serving as a speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 campaign and George McGovern's 1972 campaign. He also remained active in the presidential campaign of Senator Ted Kennedy in 1980.

5.3. Kennedy Administration

After John F. Kennedy's election, Schlesinger was offered an ambassadorship and the position of Assistant Secretary of State for Cultural Relations. However, he accepted Robert Kennedy's proposal to serve as a "sort of roving reporter and troubleshooter." On January 30, 1961, he resigned from Harvard and was appointed Special Assistant to the President. During his tenure in the White House, he primarily worked on Latin American affairs and as a speechwriter.

In February 1961, Schlesinger was first informed of the "Cuba operation," which ultimately became the Bay of Pigs Invasion. He strongly opposed the plan, conveying his concerns in a memorandum to the president, asserting that "at one stroke you would dissipate all the extraordinary good will which has been rising toward the new Administration through the world. It would fix a malevolent image of the new Administration in the minds of millions." However, he also proposed a controversial alternative, suggesting, "Would it not be possible to induce Castro to take offensive action first? He has already launched expeditions against Panama and against the Dominican Republic. One can conceive a black operation in, say, Haiti which might in time lure Castro into sending a few boatloads of men on to a Haitian beach in what could be portrayed as an effort to overthrow the Haitian regime. If only Castro could be induced to commit an offensive act, then the moral issue would be butted, and the anti-US campaign would be hobbled from the start."

During the Cabinet deliberations, Schlesinger chose to "shrank into a chair at the far end of the table and listened in silence" as the Joint Chiefs of Staff and CIA representatives argued for the invasion. Despite sending several memos opposing the strike with his friend, Senator William Fulbright, Schlesinger held back his opinion during the meetings, reluctant to undermine the President's desire for a unanimous decision. Following the invasion's failure, Schlesinger expressed deep regret, stating, "In the months after the Bay of Pigs, I bitterly reproached myself for having kept so silent during those crucial discussions in the cabinet room. ... I can only explain my failure to do more than raise a few timid questions by reporting that one's impulse to blow the whistle on this nonsense was simply undone by the circumstances of the discussion." President Kennedy, after the initial furor subsided, light-heartedly remarked that Schlesinger "wrote me a memorandum that will look pretty good when he gets around to writing his book on my administration. Only he better not publish that memorandum while I'm still alive!"

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, Schlesinger was not a member of the executive committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM), but he assisted UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson II in drafting his presentation of the crisis to the UN Security Council. In the same month, Schlesinger expressed concern about a potential "tremendous advantage" that "all-out Soviet commitment to cybernetics" could provide the Soviets. He warned that "by 1970 the USSR may have a radically new production technology, involving total enterprises or complexes of industries, managed by closed-loop, feedback control employing self-teaching computers." This concern was based on the Soviet scientists' vision of an algorithmic governance of the economy through an internet-like computer network, particularly proposed by Alexander Kharkevich.

After President Kennedy's assassination on November 22, 1963, Schlesinger resigned from his position in January 1964. He subsequently wrote his acclaimed memoir/history of the Kennedy administration, A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, which earned him his second Pulitzer Prize in 1966.

5.4. Later Political Stances

Following his service in the Kennedy administration, Schlesinger remained a steadfast Kennedy loyalist throughout his life. He actively campaigned for Robert F. Kennedy's tragic 1968 presidential campaign and later supported Senator Edward M. Kennedy in 1980. At the request of Robert Kennedy's widow, Ethel Kennedy, he authored the biography Robert Kennedy and His Times, published in 1978.

Schlesinger was a vocal critic of Richard Nixon both as a candidate and during his presidency. His prominent status as a liberal Democrat and his outspoken disdain for Nixon led to his inclusion on Nixon's infamous master list of political opponents. Ironically, Nixon would become his next-door neighbor in the years following the Watergate scandal.

Even after retiring from teaching in 1994, Schlesinger continued his involvement in politics through his writings and public speaking. He was critical of the Clinton Administration, particularly resisting President Clinton's appropriation of his "Vital Center" concept in an article for Slate in 1997. Schlesinger was also a strong opponent of the 2003 Iraq War, which he deemed a "misadventure." He specifically criticized the media for failing to adequately cover reasoned arguments against the war.

6. Major Writings and Intellectual Contributions

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. was a prolific writer whose works profoundly influenced the understanding of American history and political thought. His intellectual contributions spanned historical interpretation, social criticism, and the articulation of a distinctive liberal philosophy.

6.1. Key Books and Themes

Schlesinger's literary output included numerous influential books, each exploring significant periods or concepts in American history and politics:

- Orestes A. Brownson: A Pilgrim's Progress (1939)

- The Age of Jackson (1945): This book, which covered the intellectual environment of Jacksonian democracy, earned him his first Pulitzer Prize for History in 1946.

- The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (1949): In this work, Schlesinger presented a strong case for the New Deal policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was a foundational text for postwar liberalism, sharply criticizing both unregulated capitalism and those liberals, such as Henry A. Wallace, who advocated for coexistence with communism.

- What About Communism? (1950)

- The General and the President, and the Future of American Foreign Policy (1951)

- The Age of Roosevelt series:

- The Crisis of the Old Order: 1919-1933 (1957)

- The Coming of the New Deal: 1933-1935 (1958)

- The Politics of Upheaval: 1935-1936 (1960)

- Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference? (1960)

- The Politics of Hope (1962): In this book, Schlesinger characterized conservatives as the "party of the past" and liberals as the "party of hope," advocating for overcoming the divisions between them.

- Paths of American Thought (1963), edited with Morton White

- A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House (1965): This detailed account of the Kennedy administration won him his second Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography in 1966.

- The MacArthur Controversy and American Foreign Policy (1965)

- The Bitter Heritage: Vietnam and American Democracy, 1941-1966 (1967)

- Congress and the Presidency: Their Role in Modern Times (1967)

- Violence: America in the Sixties (1968)

- The Crisis of Confidence: Ideas, Power, and Violence in America (1969)

- The Origins of the Cold War (1970)

- The Imperial Presidency (1973): This significant work, reissued with a 79-page epilogue in 1989 and a new 16-page introduction in 2004, analyzed the expansion of presidential power, especially during the Nixon era.

- Robert Kennedy and His Times (1978): A popular biography of Robert F. Kennedy, later adapted into a 1985 TV miniseries.

- Creativity in Statecraft (1983)

- The Almanac of American History (1983), revised in 2004

- The Cycles of American History (1986): A collection of essays and articles, it included "The Cycles of American Politics," an early work on the topic that was influenced by his father's historical studies on cycles.

- JFK Remembered (1988)

- War and the Constitution: Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt (1988)

- Cleopatra (1988), with Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, featuring an introductory essay by Schlesinger

- Is the Cold War Over? (1990)

- The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society (1991): In this book, he articulated his leading opposition to multiculturalism in the 1980s.

- 20th Century Day by Day: 100 Years Of News From January 1, 1900, to December 31, 1999 (2000)

- A Life in the 20th Century, Innocent Beginnings, 1917-1950 (2000): His autobiography, Volume 1.

- War and the American Presidency (2004)

- Journals 1952-2000 (2007): Published posthumously, this 894-page book was a distillation of 6,000 pages of his diaries, edited by his sons Andrew and Stephen Schlesinger.

- Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life With John F Kennedy (2011): Featuring Mrs. Kennedy's interview shortly after her husband's assassination.

Schlesinger also wrote a foreword to a book on Vladimir Putin in 2003, published by Chelsea House Publishers. His papers are preserved and available at the New York Public Library.

6.2. Liberalism, Social Criticism, and Historical Interpretation

Schlesinger's core philosophical contributions revolved around his concept of the "Vital Center" and his interpretation of American liberalism. He championed a pragmatic and moderate liberalism, as exemplified by the New Deal, positioning it against the extremes of both unregulated capitalism and communism. In The Vital Center, he argued for a democratic and anti-totalitarian left that was committed to individual liberty and social justice, distinguishing it from those on the left who were seen as too accommodating to communism.

He viewed American history through the lens of cyclical patterns, influenced by his father's work, suggesting a recurring oscillation between periods of public purpose and private interest. As a social critic, he applied this framework to contemporary issues, such as the perceived overreach of presidential power, which led to his influential work The Imperial Presidency. He criticized the concentration of power in the executive branch, asserting that it undermined the constitutional balance of powers.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Schlesinger became a prominent critic of multiculturalism, particularly in education. In The Disuniting of America, he expressed concerns that an excessive emphasis on group identity could lead to fragmentation rather than unity within American society. His works consistently reflected a belief in a shared national identity and the importance of common American ideals.

7. Personal Life

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. was initially named Arthur Bancroft Schlesinger at birth, but he adopted the signature "Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr." from his mid-teens. He was married twice. His first marriage was to author and artist Marian Cannon Schlesinger, with whom he had four children. His second marriage was to Alexandra Emmet, also an artist, and he gained a son and a stepson from this union. His children include:

- Stephen Schlesinger (born 1942), a notable author of books on foreign affairs and former director of the World Policy Institute.

- Katharine Kinderman (1942-2004), an author and producer.

- Christina Schlesinger (born 1946), a prominent artist and muralist.

- Andrew Schlesinger, a writer and editor.

- Robert Schlesinger, a writer and editor.

8. Awards and Honors

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. received numerous prestigious awards and honors throughout his distinguished career, recognizing his significant contributions to history, literature, and public life.

- 1946**: Pulitzer Prize for History for The Age of Jackson.

- 1955**: Elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- 1958**: Bancroft Prize for The Crisis of the Old Order: 1919-1933.

- 1958**: Francis Parkman Prize for The Crisis of the Old Order: 1919-1933.

- 1966**: National Book Award in History and Biography for A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House.

- 1966**: Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography for A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House.

- 1978**: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.

- 1979**: National Book Award in Biography for Robert Kennedy and His Times.

- 1987**: Elected member of the American Philosophical Society.

- 1998**: National Humanities Medal.

- 2003**: Special Four Freedoms Award.

- 2006**: Paul Peck Award.

- 2006**: Niebuhr Medal, awarded by Elmhurst College to individuals exemplifying the ideals of Reinhold Niebuhr and H. Richard Niebuhr. Schlesinger was greatly influenced by Reinhold Niebuhr's cautious realism and advocacy for greater humility in American foreign policy.

9. Assessment and Legacy

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.'s impact on historical scholarship and public life was substantial, making him one of the most prominent intellectuals of his era. His legacy is characterized by his influential contributions to the understanding of American liberalism, alongside critical perspectives on his work.

9.1. Contributions to Historical Scholarship and Liberalism

Schlesinger significantly shaped the field of American history, particularly the historiography of 20th-century American liberalism. His multi-volume The Age of Roosevelt series provided a foundational narrative of the New Deal, while A Thousand Days offered an insider's perspective on the Kennedy administration, blending historical analysis with personal memoir. These works were celebrated for their narrative power, meticulous detail, and engagement with major political figures and decisions.

He was a leading voice for liberalism and democratic ideals, particularly through his concept of the "Vital Center". This idea provided an intellectual framework for postwar liberalism, arguing for a robust defense of democratic principles against totalitarianism and unchecked capitalism. His role as a "court historian" within the Kennedy White House cemented his unique position as both an academic and an active participant in historical events. His ability to articulate complex political and historical ideas to a broad public made him a highly influential public intellectual. He was seen as a defender of the common person and a proponent of social progress through his advocacy for progressive policies and his critical views on oppressive regimes or actions that undermined democracy.

9.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his accolades, Schlesinger's work and political stances drew criticisms from various scholars and commentators. Some historians, like Richard Aldous, labeled him an "imperial historian" for his perceived willingness to undertake public relations for the American empire, suggesting his historical accounts sometimes served to legitimize political power rather than critically examine it. Conversely, others, such as Sean Wilentz, argued that Schlesinger was, in fact, an "anti-imperial historian," challenging the notion that his work uncritically supported American foreign policy.

Critics from the political right, such as Hilton Kramer, often took issue with his liberal leanings and interpretations of American history. From the left, figures like Noam Chomsky critiqued intellectuals, including Schlesinger, for what they perceived as a failure to sufficiently challenge state power and official narratives, particularly regarding foreign policy. His opposition to multiculturalism in his later career also generated significant debate, with some arguing that his stance overlooked the importance of diverse cultural identities within American society. Furthermore, his inclusion on Richard Nixon's infamous "enemies list" highlights the highly polarized political landscape in which he operated and his willingness to take strong positions that provoked his adversaries.

10. Death

On February 28, 2007, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. suffered a heart attack while dining with his family at a steakhouse in Manhattan. He was transported to New York Downtown Hospital, where he died at the age of 89. His obituary in The New York Times described him as a "historian of power." He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

11. External links

- [http://archives.nypl.org/mss/17775 Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. papers 1922-2007] at the New York Public Library

- [http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/Schl In Depth interview with Schlesinger, December 3, 2000] (from C-SPAN)

- [http://www.washingtonian.com/blogarticles/people/capitalcomment/6749.html Arthur Schlesinger Dishes Dirt] (from Washingtonian)

- [https://web.archive.org/web/20081218181450/http://www.geocities.com/billyspencer2000/schlesinger.htm An incredible writer and a proud Liberal all his life.]

- [http://www.cceia.org/people/data/arthur_m__schlesinger.html Resources by Arthur Schlesinger] at the Carnegie Council