1. Early Life and Education

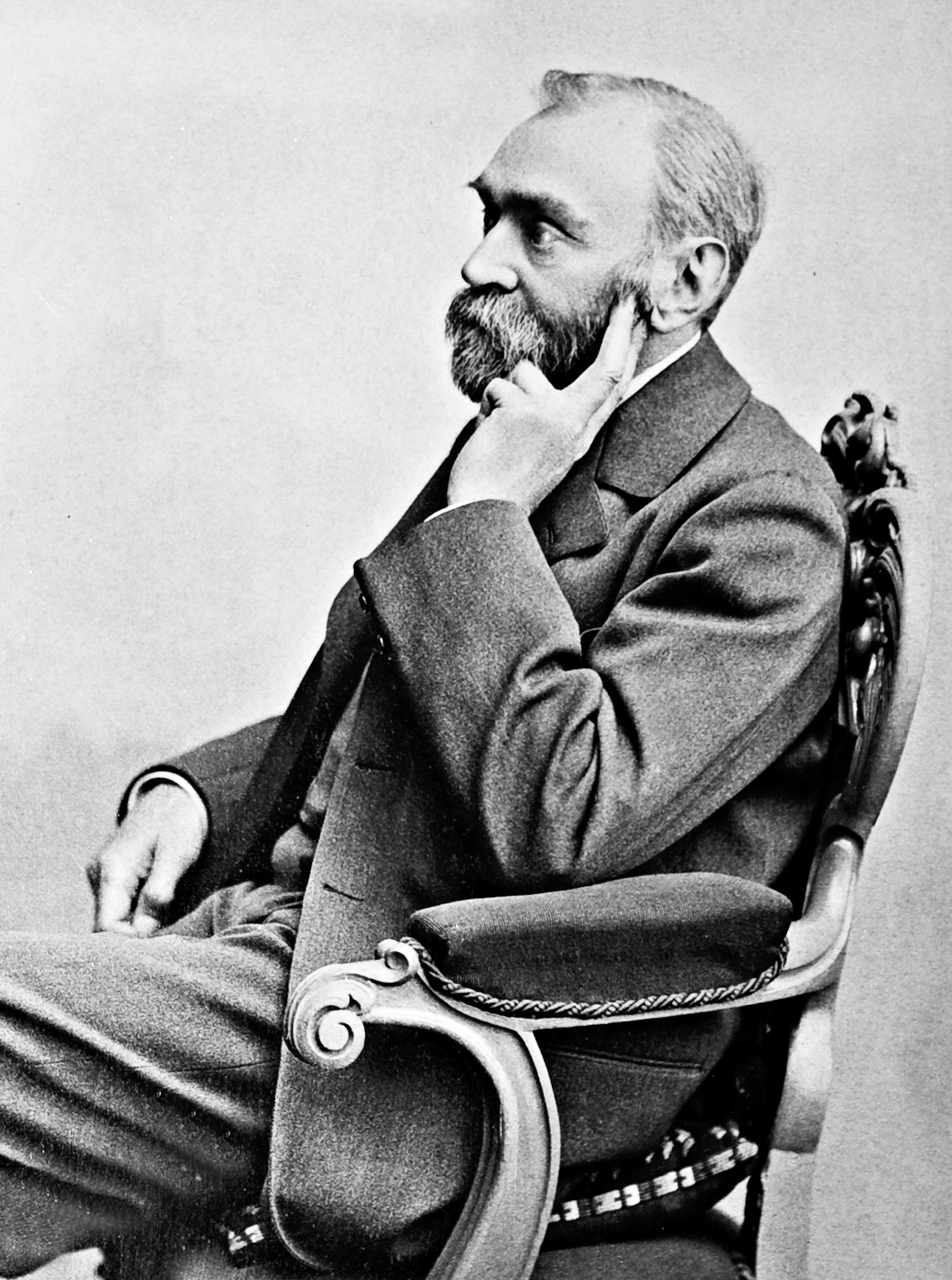

Alfred Nobel was born in Stockholm, Sweden, on 21 October 1833. He was the third son of Immanuel Nobel (1801-1872), an inventive engineer and architect, and Andriette Nobel (née Ahlsell 1805-1889). His parents, who married in 1827, had eight children, though only Alfred and his three brothers-Robert (born 1829), Ludvig (born 1831), and Emil (born 1843)-survived beyond childhood. The family was initially impoverished. His mother, Andriette Nobel, who came from a wealthy family, opened a grocery store to support the family during this period of financial hardship. Through his father, Alfred Nobel was a descendant of the notable Swedish scientist Olaus Rudbeck (1630-1702). Immanuel Nobel, an alumnus of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, encouraged Alfred's early interest in engineering and explosives, teaching him fundamental principles from a young age.

Following several business setbacks, including the loss of building material barges, Immanuel Nobel faced bankruptcy. In 1837, he moved alone to Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, where he found success as a manufacturer of machine tools and explosives. He invented the veneer lathe, which was instrumental in the production of modern plywood, and began developing naval mines. These mines proved effective in deterring the Royal Navy from attacking Saint Petersburg during the Crimean War (1853-1856). In 1842, the rest of the Nobel family joined him in Saint Petersburg. With newfound prosperity, Alfred's parents arranged for private tutors for their sons. Alfred excelled in his studies, particularly in chemistry and languages, becoming fluent in Swedish, English, French, German, Russian, and Italian. His formal schooling was limited to 18 months, from 1841 to 1842, at the Jacobs Apologistic School in Stockholm; he never attended a university.

Nobel also cultivated significant literary skills, including writing poetry in English. His prose tragedy in four acts, Nemesis, focuses on the Italian noblewoman Beatrice Cenci. This work was printed while he was on his deathbed, but its entire stock was destroyed immediately after his death, except for three copies, due to its controversial nature, being considered scandalous and blasphemous. It was eventually published in Sweden in 2003 and has since been translated into Slovenian, French, Italian, and Spanish.

2. Scientific Career and Inventions

Nobel's scientific career was primarily defined by his groundbreaking contributions to the field of chemistry and engineering, particularly in the development of explosives.

2.1. Nitroglycerin Research

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin, then traveled to Paris in 1850 to further his studies. There, he met Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero, who had synthesized nitroglycerin three years prior. Sobrero strongly cautioned against the use of nitroglycerin, deeming it too dangerous and unpredictable, as it would explode when subjected to varying heat or pressure. However, Nobel became fascinated with finding a way to control and commercialize nitroglycerin as a usable explosive, recognizing its immense power, far exceeding that of gunpowder.

In 1851, at the age of 18, Nobel spent a year in the United States for study, working briefly under the Swedish-American inventor John Ericsson, known for designing the American Civil War ironclad, USS Monitor. Nobel filed his first patent in 1857, an English patent for a gas meter. His first Swedish patent, granted in 1863, concerned "ways to prepare gunpowder." The Nobel family factory in Russia produced armaments for the Crimean War (1853-1856). However, the business struggled to transition back to civilian production after the war concluded, leading to their bankruptcy.

In 1859, Nobel's father entrusted his factory to his second son, Ludvig Nobel, who significantly improved the business. Alfred and his parents returned to Sweden from Russia, where Alfred dedicated himself to the study of explosives, focusing on the safe manufacture and use of nitroglycerin. He invented a detonator in 1863 and designed the blasting cap in 1865. On 3 September 1864, a catastrophic explosion occurred at the family's factory in Heleneborg, Stockholm, Sweden, where nitroglycerin was being prepared. This accident killed five people, including Nobel's younger brother, Emil Oskar Nobel. Following this tragedy, Nobel was deprived of his license to produce explosives within Stockholm's city limits. Undeterred, Nobel established the company Nitroglycerin AB in Vinterviken, moving his operations to a more isolated area to continue his research.

2.2. Dynamite

Nobel's persistent efforts to stabilize nitroglycerin led to his most famous invention, dynamite, in 1867. He discovered that when nitroglycerin was incorporated into an absorbent, inert substance like kieselguhr (diatomaceous earth), it became safer and more convenient to handle. This mixture, patented in the US and the UK in 1867, transformed the use of explosives. Nobel first publicly demonstrated dynamite that year at a quarry in Redhill, Surrey, England. To help restore his reputation and improve the image of his business, which had been tarnished by earlier controversies involving dangerous explosives, Nobel considered naming the powerful substance "Nobel's Safety Powder." However, he ultimately chose "Dynamite," a name derived from the Greek word δύναμιςdynamisGreek, Ancient, meaning "power."

Dynamite rapidly gained widespread adoption due to its ease of use and enhanced safety compared to pure nitroglycerin. It revolutionized industries such as mining, quarrying, and the construction of transport networks like tunnels, roads, and railways, especially when used in conjunction with new technologies like diamond-core and air drills. This invention propelled Nobel to significant financial success and made him a leading figure in the global industrial landscape.

2.3. Other Explosives

Nobel continued his research into explosives, leading to further innovations beyond dynamite. In 1875, he invented gelignite, also known as blasting gelatin. This substance was created by combining nitroglycerin with various nitrocellulose compounds, similar to collodion, and incorporating another nitrate explosive. The resulting transparent, jelly-like material was more powerful than dynamite. Gelignite, patented in 1876, was followed by a host of similar combinations, which were further modified by the addition of potassium nitrate and other substances. Gelignite proved more stable, powerful, and transportable than previous compounds, and its convenient form allowed it to be easily fitted into bored holes used in drilling and mining. It became the standard technology for mining during the "Age of Engineering," bringing Nobel substantial financial success, albeit at a cost to his health due to his strenuous work and exposure to chemicals.

An offshoot of this extensive research resulted in Nobel's invention of ballistite, patented in 1887. Ballistite was a precursor to many modern smokeless powder explosives and is still used today as a rocket propellant. It was a powerful, smokeless gunpowder, composed of equal parts of guncotton and nitroglycerin.

2.4. Patents and Business Ventures

Alfred Nobel amassed an impressive portfolio of 355 patents internationally during his lifetime. By the time of his death, his business empire had established more than 90 armaments factories worldwide, a fact that stands in stark contrast to his later reputation as a champion of peace.

Nobel was recognized for his scientific achievements, being elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1884. This institution would later be responsible for selecting laureates for two of the Nobel Prizes: physics and chemistry. In 1893, he received an honorary doctorate from Uppsala University.

His brothers, Ludvig and Robert, founded the oil company Branobel, which operated primarily in Baku, Azerbaijan, and also in Cheleken, Turkmenistan. They became immensely wealthy through their ventures in the developing oil regions. Alfred Nobel himself invested significantly in Branobel, further expanding his vast fortune. In 1894, he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, a Swedish iron and steel producer, which he then transformed into a major manufacturer of cannons and other military armaments. Beyond explosives and armaments, Nobel also experimented with creating synthetic materials, including rubber, artificial leather, and artificial silk, as well as artificial gemstones.

His involvement in arms manufacturing also led to significant controversy. In 1890, a dispute arose when an acquaintance, British inventor James Dewar, acquired a patent in England that was very similar to Nobel's ballistite patent. Despite Nobel's preference for a negotiated settlement, his company and lawyers pushed for a lawsuit. The protracted legal battle, which extended until 1895 and involved Dewar's patented smokeless powder, Cordite, ultimately resulted in Nobel's defeat. During this period, he was even accused of high treason against France for selling Ballistite to Italy, leading to his imprisonment for two months and the closure of his smokeless powder factory in France. This chain of events contributed to his decision to move from Paris to Sanremo, Italy.

3. Personal Life

Alfred Nobel led a largely solitary life, often experiencing periods of melancholy and depression. Despite his immense wealth and global reach, he never married and had no children.

3.1. Personality and Relationships

Biographers have noted that Nobel experienced at least three significant romantic interests throughout his life. His first love was in Russia with a girl named Alexandra, who ultimately rejected his proposal of marriage.

In 1876, the Austro-Bohemian Countess Bertha von Suttner became his secretary. However, her tenure was brief, as she soon left to marry her previous lover, Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner. Despite the short duration of their direct contact, Bertha and Alfred maintained a correspondence until his death in 1896. This ongoing exchange, particularly Bertha's active involvement in the peace movement and her authorship of the influential book Lay Down Your Arms!, is widely believed to have influenced Nobel's decision to include a Nobel Peace Prize in his will. Bertha von Suttner herself was awarded the 1905 Nobel Peace Prize for her dedicated peace activities.

Nobel's longest-lasting romantic relationship was an 18-year connection with Sofie Hess, a flower shop employee from Celje, whom he met in 1876 in Baden bei Wien. The depth of their relationship was revealed through a collection of 221 letters Nobel sent to Hess over 15 years. Nobel, then 43, and Hess, 26, maintained a relationship that was not merely platonic. It concluded when Hess became pregnant by another man, though Nobel continued to provide her financial support until she married the child's father to avoid societal ostracization.

However, the contents of these letters also revealed a darker side of Nobel's character. Hess was a Jewish Christian, and Nobel's correspondence included remarks that have been characterized as antisemitism. For instance, he wrote: "In my experience, [Jews] never do anything out of good will. They act merely out of selfishness or a desire to show off .... among selfish and inconsiderate people they are the most selfish and inconsiderate... all others exist to be fleeced." Additionally, his letters displayed characteristics of chauvinism, as evidenced by remarks such as: "You neither work, nor write, nor read, nor think" and his self-pitying remark, "I have for years now sacrificed out of purely noble motives my time, my duties, my intellectual life, my reputation."

3.2. Health and Death

Alfred Nobel reportedly suffered from various health issues throughout his life. In his letters to Sofie Hess, he described persistent pain, debilitating migraines, and "paralyzing" fatigue. Some scholars have suggested these symptoms might indicate fibromyalgia. However, his concerns were often dismissed by doctors at the time as hypochondria, which further contributed to his feelings of depression. By 1895, Nobel had developed angina pectoris, a condition characterized by chest pain due to reduced blood flow to the heart.

On 27 November 1895, he finalized his last will and testament in Paris, secretly allocating the majority of his wealth to fund the future Nobel Prize awards, a decision unknown to his family at the time.

Alfred Nobel died on 10 December 1896, at his villa in Sanremo, Italy, at the age of 63. He suffered a stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage, which first caused partial paralysis, followed by his death. He died in the presence of his servants, as his relatives were unable to reach him in time. He is buried in Norra begravningsplatsen in Stockholm, Sweden. Due to his extensive experimentation with explosives, his demanding work habits, and the decline in his health towards the end of the 1870s, some hypothesize that chronic nitroglycerin poisoning may have been a contributing factor to his anginal pains and premature death.

3.3. Residences

Nobel's extensive business interests across Europe and America meant he traveled extensively throughout his life, maintaining residences in various countries. From 1865 to 1873, he resided in Krümmel, which is now part of the municipality of Geesthacht, near Hamburg, Germany. From 1873 to 1891, his primary residence was a house on Avenue Malakoff in Paris, France.

In 1891, after being controversially accused of high treason against France for selling his explosive ballistite to Italy, Nobel moved from Paris to Sanremo, Italy. There, he acquired Villa Nobel, a property overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, where he spent his final years and ultimately died in 1896.

In 1894, upon his acquisition of the Bofors-Gullspång company, the Björkborn Manor in Karlskoga, Sweden, was included in the purchase. Nobel used this manor as his summer residence. Today, Björkborn Manor has been preserved and operates as a museum dedicated to his life and work.

4. The Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes stand as Nobel's most enduring legacy, recognizing global achievements in various fields.

4.1. Motivation and The Will

A widely known, though historically debated, anecdote often cited as the origin of the Nobel Prize concerns a premature obituary. In 1888, following the death of his brother Ludvig, several newspapers mistakenly published obituaries for Alfred. One French newspaper, in particular, condemned him for his invention of military explosives, stating: Le marchand de la mort est mortFrench ("The merchant of death is dead"). The obituary went on to declare, "Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday." While historians question the exact existence of this specific obituary and some dismiss the story as mythical, it is widely believed that Nobel, upon reading such a condemnation, was appalled at the idea of being remembered solely as a "merchant of death." This reputational shock is often credited as the catalyst for his decision to dedicate the majority of his fortune to establishing the Nobel Prizes, aiming to leave behind a more positive legacy for humankind.

On 27 November 1895, at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, Nobel formally signed his last will and testament. In this document, he set aside the bulk of his substantial estate to establish the Nobel Prizes, stipulating that they be awarded annually "without distinction of nationality." After accounting for taxes and specific bequests to individuals, Nobel's will allocated 94% of his total assets-a staggering 31.23 M SEK (Swedish Kronor) at the time-to fund the five original Nobel Prizes. By 2022, the Nobel Foundation, responsible for managing this endowment, had approximately 6.00 B SEK in invested capital.

4.2. Prize Categories and Interpretations

Nobel's will specified five original prize categories. The first three were to be awarded for eminence in physical science, chemistry, and medical science or physiology. The fourth prize was designated for literary work "in an ideal direction" (i idealisk riktningSwedish in Swedish). The fifth prize, the Nobel Peace Prize, was to be given to the person or society that rendered the greatest service to the cause of international fraternity, in the suppression or reduction of standing armies, or in the establishment or furtherance of peace congresses.

The phrasing for the literature prize, "in an ideal direction," proved cryptic and led to considerable confusion and debate for many years. The Swedish Academy initially interpreted "ideal" as "idealistic" (idealistiskSwedish), using this interpretation as a basis to withhold the prize from important but less romantic authors, such as Henrik Ibsen and Leo Tolstoy. This interpretation has since been revised, allowing for the prize to be awarded to a broader range of authors, including those not traditionally associated with literary idealism, such as Dario Fo and José Saramago.

Furthermore, Nobel's will provided room for interpretation by the bodies he named for deciding on the physical sciences and chemistry prizes, as he had not consulted them before making his will. While his testament specified awards for discoveries or inventions in physical sciences and discoveries or improvements in chemistry, it did not explicitly define the distinction between science and technology. Since the chosen deciding bodies were primarily concerned with academic science, the prizes were more frequently awarded to scientists rather than engineers, technicians, or other inventors.

In 1968, Sweden's central bank, Sveriges Riksbank, celebrated its 300th anniversary by donating a substantial sum of money to the Nobel Foundation. This donation was designated for the establishment of a sixth prize in the field of economics, awarded "in memory of Alfred Nobel." This award, officially known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, has generated controversy over whether it is a legitimate "Nobel Prize," as it was not part of Alfred Nobel's original will. In 2001, Alfred Nobel's great-great-nephew, Peter Nobel (born 1931), publicly requested that the Bank of Sweden differentiate its economics award from the five original prizes.

5. Criticism and Controversy

Alfred Nobel's life and legacy have been subject to various criticisms, particularly concerning his involvement in the arms industry and aspects of his personal views.

5.1. Arms Manufacturing

Nobel's leading role in the manufacturing and sale of weapons and explosives, most notably through his ownership and development of Bofors into a major armaments producer, raises significant ethical questions. This involvement stands in stark contrast to his establishment of the Nobel Peace Prize, leading to ongoing debate about his motivations. Nobel himself held a paradoxical view that the creation of increasingly powerful weapons would act as a deterrent, thus preventing wars. However, the widespread availability of high-performance explosives, largely due to his inventions, arguably contributed to the intensification of modern warfare, rather than its cessation.

His pursuit of explosive innovation also led to personal and legal difficulties. In 1890, a dispute arose over a patent in England, where an acquaintance reportedly acquired a patent very similar to Nobel's ballistite. Although Nobel favored a peaceful resolution, his company and legal team insisted on a lawsuit. The protracted legal battle, which lasted until 1895, ultimately resulted in a loss for Nobel. Furthermore, he faced accusations of high treason against France for selling ballistite to Italy, leading to a two-month imprisonment and the closure of his smokeless powder factory in France. These events significantly impacted him, contributing to his decision to relocate to Sanremo, Italy.

5.2. Personal Views

Criticism has also been directed at Alfred Nobel for displaying antisemitic and chauvinistic sentiments, as revealed in his private correspondence with Sofie Hess. In his letters, he wrote about Jewish people: "In my experience, [Jews] never do anything out of good will. They act merely out of selfishness or a desire to show off .... among selfish and inconsiderate people they are the most selfish and inconsiderate... all others exist to be fleeced." His letters also exhibited chauvinistic attitudes towards women, as seen in his comments to Hess, such as "You neither work, nor write, nor read, nor think," and his self-pitying remark, "I have for years now sacrificed out of purely noble motives my time, my duties, my intellectual life, my reputation."

5.3. Legacy and Reputation

The debate surrounding Nobel's motivations for establishing the prizes persists, with some suggesting they were intended to cleanse his reputation as a "merchant of death." His life is often characterized by paradox and contradiction: he was a brilliant, wealthy industrialist who developed tools of mass destruction, yet also a solitary and melancholic individual who established the world's most prestigious awards for peace and human progress. The ultimate interpretation of his legacy balances his role as an inventor of destructive substances with his visionary philanthropic endeavor.

6. Legacy and Memorials

Alfred Nobel's lasting impact is multifaceted, encompassing the transformative power of his inventions and the enduring influence of the prizes that bear his name, ensuring his remembrance across the globe.

6.1. Impact of Inventions

The invention of dynamite and other explosives by Alfred Nobel had a profound and transformative effect on industrial development worldwide. These powerful substances revolutionized mining operations, significantly improving efficiency and safety in extracting minerals and resources. They also played a critical role in large-scale infrastructure projects, enabling the efficient construction of tunnels through mountains, the blasting of rock for railway lines, and the excavation of canals, dramatically accelerating industrial progress and reshaping landscapes. While primarily intended for civilian applications, Nobel's explosives also found uses in warfare, ironically intensifying conflict despite his personal aspirations for peace.

6.2. The Nobel Prizes' Enduring Influence

The Nobel Prizes, established through Alfred Nobel's will, continue to hold immense global significance. Annually recognizing outstanding achievements in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, and Peace, as well as Economics, the prizes serve to promote human progress and inspire individuals and organizations to strive for excellence and contribute to the betterment of humankind. The awards are presented at ceremonies held in Stockholm, Sweden (for Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, and Literature), and Oslo, Norway (for Peace).

6.3. Honors and Memorials

Alfred Nobel's legacy is commemorated in various ways globally. The synthetic element with atomic number 102, nobelium, was named in his honor. His name also lives on in companies such as Dynamit Nobel and AkzoNobel, which are descended from mergers involving companies he founded.

Several sites associated with his life have been preserved as memorials. Björkborn Manor in Karlskoga, Sweden, which served as his last Swedish residence and summer home, is now a museum dedicated to his life. The Nobel Museum in the Old Town of Stockholm celebrates his life, the history of the Nobel Prize, and the achievements of Nobel laureates.

Another memorial is a monument to Alfred Bernhard Nobel located in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Australia. Additionally, a Japanese confectionery company, Nobel Seika, bears his name, though it has no direct connection to Alfred Nobel himself. It was named after the Nobel Prize in 1949, following the recognition of Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa with the Nobel Prize in Physics, due to a friendship between the company's founder and Yukawa.