1. Early Life and Background

Albert Göring's early life was shaped by his family's prominent connections and the unique circumstances surrounding his birth and upbringing, providing a crucial backdrop to his later humanitarian actions.

1.1. Family Background and Birth

Albert Günther Göring was born on 9 March 1895 in Friedenau, a suburb of Berlin, German Empire. He was the fifth child of Heinrich Ernst Göring, a former Reichskommissar to German South-West Africa and German Consul General to Haiti, and Franziska "Fanny" Tiefenbrunn, who hailed from a Bavarian peasant family. The Göring family had connections to several notable figures, including German Counts Zeppelin, such as aviation pioneer Ferdinand von Zeppelin; the German nationalist art historian Herman Grimm; the Swiss art and cultural historian Jacob Burckhardt; Swiss diplomat and President of the International Red Cross Carl Jacob Burckhardt; the Merck family, owners of the German pharmaceutical giant Merck KGaA; and German Catholic writer and poet Gertrud von Le Fort.

The Göring children were raised partly in the Veldenstein and Mauterndorf castles, homes of their aristocratic godfather, Hermann Epenstein Ritter von Mauternburg. Epenstein, a prominent physician, served as a surrogate father due to Heinrich Göring's frequent absences. Epenstein, who was of Jewish heritage, began an affair with Franziska Göring approximately a year before Albert's birth. A strong physical resemblance between Albert Göring and Epenstein led to speculation that Epenstein was Albert's biological father, which would have made Albert one-quarter Jewish by Nuremberg Laws standards. However, Franziska Göring had accompanied her husband to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and lived there with him between March 1893 and mid-1894, making this paternity claim highly unlikely.

1.2. Education and World War I Service

Albert Göring pursued studies in mechanical engineering. Unlike his older brother Hermann, who became deeply involved in politics and military affairs, Albert initially pursued a relatively ordinary life, engaging in the film industry for his livelihood. During World War I, Albert served in the trenches as a signal engineer with the Imperial German Army.

2. Opposition to Nazism and Humanitarian Activities

Albert Göring's deep-seated opposition to Nazism manifested in numerous acts of defiance and humanitarian assistance, leveraging his unique position to save lives during one of history's darkest periods.

2.1. Personal Opposition to Nazism

Upon the rise of the Nazi Party in 1933, Albert Göring developed a profound disdain for Nazism and its brutal ideology, particularly its anti-Jewish policies and human rights violations. He was a bon vivant by nature, a character he seemed to have inherited from his godfather, and was set for an "unremarkable life" as a filmmaker until the Nazis came to power.

His resistance to the regime is illustrated by several anecdotal stories. For instance, Albert reportedly joined a group of Jewish women who had been forced by the SS to scrub a street. An SS officer in charge, upon inspecting Albert's identification, recognized the name and ordered the scrubbing activity to cease, fearing repercussions for publicly humiliating Hermann Göring's brother.

2.2. Acts of Rescue and Assistance

Albert Göring actively used his influence to protect and assist those persecuted by the Nazi regime. He intervened to secure the release of his Jewish former boss, Oskar Pilzer, after Pilzer's arrest by the Nazis, subsequently helping Pilzer and his family escape from Germany. He extended similar assistance to numerous other German dissidents, facilitating their escape from persecution. On many occasions, he forged his brother Hermann's signature on transit documents to enable dissidents to flee the country. When caught, he would exploit his brother's immense influence to secure his own release.

2.3. Work at Škoda Works and Support for Czech Resistance

Albert Göring intensified his anti-Nazi activities when he was appointed export director at the Škoda Works in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which was the occupied part of the former Czechoslovakia. In this role, he covertly encouraged minor acts of sabotage among workers and maintained contact with the Czech resistance movement, providing them with support. He also orchestrated a daring scheme to free prisoners from Nazi concentration camps. He would send trucks to the camps under the pretext of requesting laborers. These trucks would then stop in isolated areas, allowing the prisoners-including Jewish people and Soviet prisoners of war-to escape to neutral countries like Switzerland and Monaco.

3. Post-war Life and Social Reception

After the war, Albert Göring faced a new set of challenges, including interrogations by Allied forces and the social stigma associated with his infamous surname, which overshadowed his humanitarian deeds.

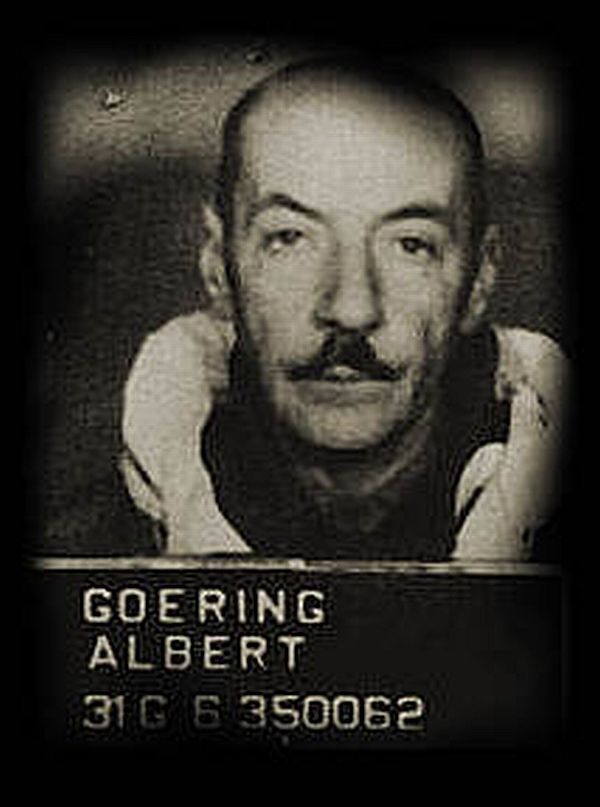

3.1. Post-war Interrogation and Trials

Following the war, Albert Göring was subjected to interrogation during the Nuremberg trials by Allied forces. Despite being the brother of one of the most prominent Nazi leaders, many individuals he had helped during the war testified in his defense, leading to his release. Shortly thereafter, he was arrested by Czechoslovak authorities. However, once the full extent of his anti-Nazi activities and humanitarian efforts became known, he was again released. During his interrogations, Albert Göring consistently maintained his anti-Nazi stance. Despite knowing that criticizing his brother Hermann could improve his own situation, he did not do so, expressing gratitude to Hermann for repeatedly protecting him from the Gestapo and helping him secure employment.

3.2. Social Stigma and Later Life

Upon his return to Germany, Albert Göring found himself shunned by society due to the widespread hatred associated with his family name. He struggled to find stable employment, managing only occasional work as a writer and translator. He lived in a modest flat, a stark contrast to the opulent, baronial splendor of his childhood. His Czech wife, Mila, divorced him, having been aware of his infidelities, and subsequently emigrated to Lima, Peru, with their daughter, Elizabeth.

Another incident occurred in 1962 in Vienna, Austria, where his 75-year-old mother was humiliated in a shop, forced to sit on a display shelf with a sign labeling her a "dirty Jew" by a German soldier. Albert intervened, showing his identification with the Göring surname, and rescued her.

In his final years, Albert Göring subsisted on a government pension. Aware that his pension payments would transfer to his wife upon his death if he were married, he married his housekeeper in 1966 as a gesture of gratitude, ensuring she would receive his pension after his passing.

3.3. Death

Albert Günther Göring died on 20 December 1966. Although he spent his last years living in Munich, Bavaria, he passed away in a hospital located in Neuenbürg, in the neighboring state of Baden-Württemberg. He died without his significant wartime anti-Nazi activities having been publicly acknowledged or widely recognized.

4. Relationship with Hermann Göring

The relationship between Albert and his notorious brother, Hermann Göring, was complex and marked by profound ideological differences, yet it also involved instances where Albert relied on Hermann's influence for protection.

The brothers were fundamentally opposite in personality and political views. While Hermann was deeply interested in politics and military affairs, Albert was apolitical. Hermann described Albert as always appearing "10 years older" than himself, perhaps due to Albert's tendency to take things too seriously. Hermann noted that they never truly had a good relationship, and their differing attitudes toward the Nazi Party led to a 12-year period of estrangement where they did not speak. Despite this, Hermann stated that they were not angry with each other, but rather grew distant due to the circumstances. He characterized Albert as quiet, preferring solitude, melancholic, and pessimistic, in contrast to his own sociable and optimistic nature. However, Hermann also acknowledged that Albert was "not a bad guy."

Despite their stark political opposition, Albert occasionally leveraged Hermann's powerful position within the Nazi regime. When Albert was arrested by the Gestapo for his anti-Nazi statements, Hermann consistently intervened to secure his release. As Edda Göring, Hermann's daughter, noted, Albert could help people financially and through his personal influence, but when higher authority or officials were involved, he relied on her father's support, which he always received. This reliance on Hermann's protection allowed Albert to continue his humanitarian efforts without facing the full wrath of the Nazi state. Before Hermann's suicide at the Nuremberg trials, Albert was granted a final visit, during which Hermann asked him to look after their family. Albert was reportedly deeply saddened by his brother's death.

5. Legacy and Public Recognition

For many decades after his death, Albert Göring's story of humanitarianism and resistance remained largely unknown to the public, overshadowed by the infamy of his brother. However, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, his contributions began to receive significant attention through various media.

5.1. Evaluation of Humanitarian Efforts

For over three decades following his death, Albert Göring received scant attention, while his brother Hermann was the subject of numerous publications. An early exception was a brief article by writer Ernst Neubach in the German weekly magazine aktuell in the early 1960s, while Göring was still alive.

Towards the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century, Albert Göring's life and work became the subject of several books and documentaries, which in turn spurred a greater number of new publications and public interest. Notable books include James Wyllie's 2006 double biography The Warlord and the Renegade, and Arno Lustiger's 2011 book RettungswiderstandGerman (Resistance to Save). William Hastings Burke's 2009 book Thirty Four detailed Göring's humanitarian efforts. A review of Burke's book in The Jewish Chronicle called for Albert Göring to be honored at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel.

However, Yad Vashem subsequently announced that Albert Göring would not be listed as Righteous Among the Nations. While acknowledging "indications that Albert Goering had a positive attitude to Jews and that he helped some people," Yad Vashem stated that there was "not sufficient proof, i.e., primary sources, showing that he took extraordinary risks to save Jews from danger of deportation and death."

5.2. Portrayal in Mass Media

Albert Göring's life has been depicted in several film documentaries and docudramas, contributing to a broader public understanding of his unique role during the Nazi era.

The first and most extensive documentary was The Real Albert Goering, produced by 3BM TV and broadcast in the United Kingdom in 1998. This documentary was later distributed internationally by the History Channel, reaching countries such as the United States in the early 2000s. Roughly a decade later, William Hastings Burke produced a documentary based on his book, further disseminating Albert's story. In 2014, Véronique Lhorme's Le Dossier Albert GöringFrench was broadcast on French television.

In January 2016, the German TV channel Das Erste aired the docudrama Der gute GöringGerman (The Good Göring), starring Barnaby Metschurat as Albert Göring and Francis Fulton-Smith as his brother Hermann. In 2018, Emmanuel Amara directed La liste GoringFrench ("Göring's List") for Toute L'HistoireFrench. Additionally, a BBC Radio 4 documentary titled The Good Göring, broadcast in January 2016, featured an investigation into Albert Göring's life by British journalist and broadcaster Gavin Esler.