1. Early Life and Education

Adrian Boult's formative years were shaped by a supportive family environment and a comprehensive musical education that laid the foundation for his distinguished career.

1.1. Early Life and Family Background

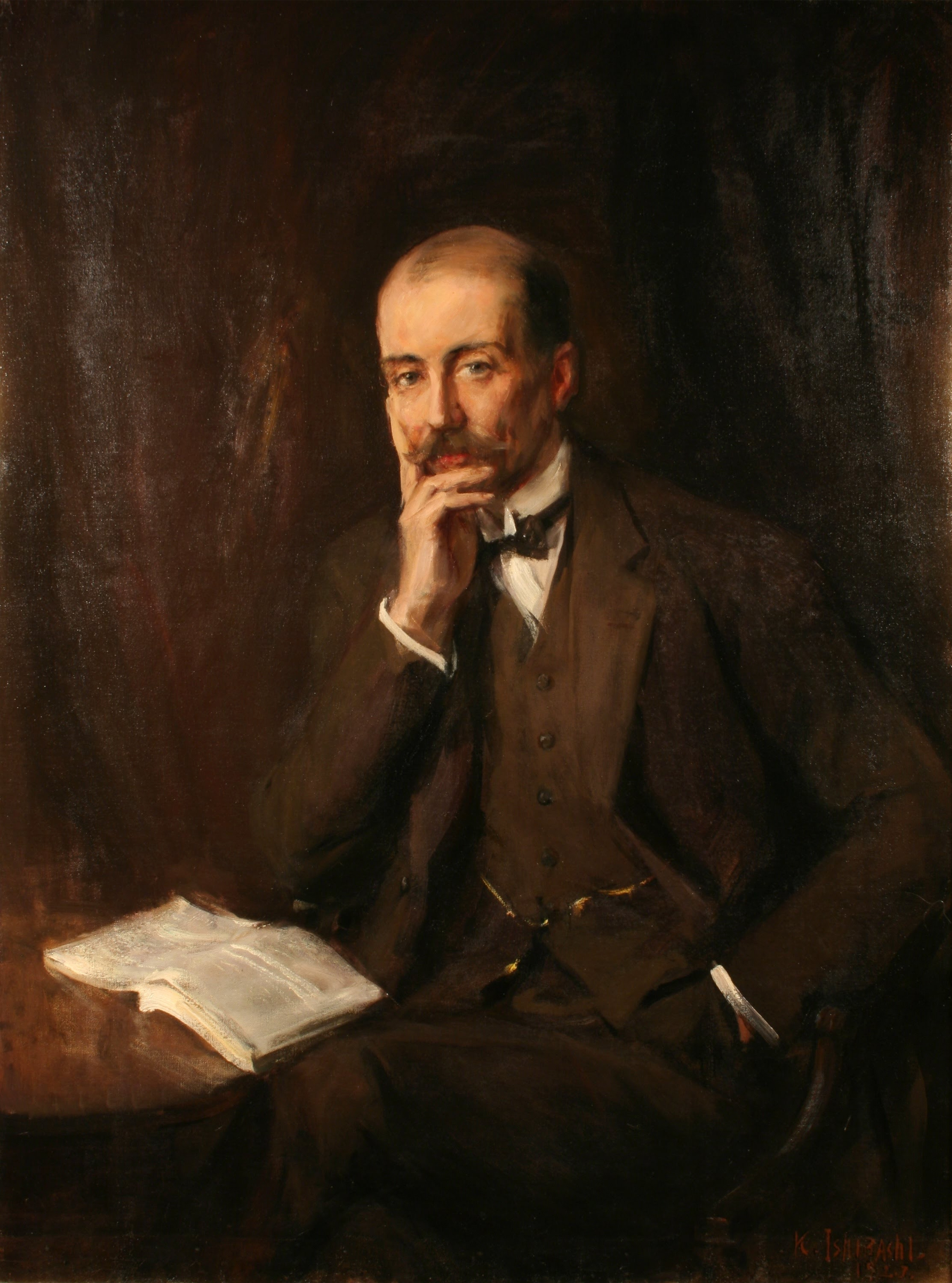

Boult was born in Chester, Cheshire, on 8 April 1889, as the second child and only son of Cedric Randal Boult (1853-1950) and Katharine Florence Barman (died 1927). His father, Cedric Boult, was a successful businessman involved in Liverpool shipping and the oil trade, and also served as a Justice of the Peace. The Boult family held a "Liberal Unitarian outlook on public affairs" and had a history of philanthropy, contributing to a nurturing environment. When Boult was two years old, his family relocated to Blundellsands, where he received a musical upbringing. From an early age, he regularly attended concerts in Liverpool, many of which were conducted by the renowned Hans Richter, fostering his early appreciation for orchestral music.

1.2. Education and Early Influences

Boult's education began at Westminster School in London. During his time there, he frequently attended concerts, witnessing performances by eminent conductors and composers such as Sir Henry Wood, Claude Debussy, Arthur Nikisch, Fritz Steinbach, and Richard Strauss. These experiences provided him with an invaluable early exposure to a wide array of musical interpretations and styles. While still a schoolboy, Boult had the opportunity to meet the composer Edward Elgar through a family friend, Leo Frank Schuster.

In 1908, Boult enrolled at Christ Church college at Oxford University, initially studying history before transitioning to music. His primary mentor in music at Oxford was the academic and conductor Hugh Allen. It was also at Oxford that he formed a lifelong friendship with Ralph Vaughan Williams. In 1909, Boult presented a paper titled Some Notes on Performance to the Oriana Society, an Oxford musical group. In this paper, he articulated three fundamental principles for an ideal musical performance: strict adherence to the composer's wishes, achieving clarity through emphasis on balance and structure, and creating music that appeared effortless. These principles remained central to his conducting philosophy throughout his career. He served as president of the University Musical Club in 1910. Beyond music, Boult was also an avid rower, stroking his college boat at Henley Royal Regatta and remaining a member of the Leander Club throughout his life.

After graduating from Oxford in 1912, Boult continued his musical studies at the Leipzig Conservatory from 1912 to 1913. While Hans Sitt led the conducting class, the most significant influence on Boult during this period was Arthur Nikisch. Boult attended all of Nikisch's rehearsals and concerts at the Gewandhaus, noting Nikisch's "astonishing baton technique and great command of the orchestra: everything was indicated with absolute precision." Boult particularly admired Nikisch for his ability to convey his intentions with minimal verbal instruction, a style that resonated with Boult's own belief that conductors should remain unobtrusive, allowing the music to speak for itself. Later, in 1913, Boult joined the musical staff of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, where he assisted with the first British production of Richard Wagner's Parsifal and observed Nikisch conducting the Ring cycle.

2. Early Conducting Career

Boult's initial foray into the professional music world saw him quickly establish himself through significant debuts, important premieres, and foundational work in music education.

2.1. Debut and Early Engagements

Boult made his professional conducting debut on 27 February 1914, at West Kirby Public Hall, leading members of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. His inaugural program showcased a diverse range of orchestral works by composers such as Bach, George Butterworth, Mozart, Schumann, Wagner, and Hugo Wolf, interspersed with arias sung by Agnes Nicholls.

During the First World War, Boult was medically deemed unfit for active service. He served as an orderly officer in a reserve unit until 1916 and was later recruited by the War Office as a translator due to his proficiency in French, German, and Italian. In his spare time, he dedicated himself to organizing and conducting concerts, some of which were financially supported by his father. His aim was to provide employment for orchestral musicians and to make music accessible to a broader audience during wartime.

In 1919, Boult succeeded Ernest Ansermet as the musical director for Sergei Diaghilev's renowned ballet company. Despite having no prior familiarity with the company's repertoire of fourteen ballets, Boult was required to quickly master complex scores such as Stravinsky's Petrushka and The Firebird, Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, and Rossini/Respighi's La Boutique fantasque. In 1921, he also conducted the British Symphony Orchestra for Vladimir Rosing's Opera Week at Aeolian Hall.

2.2. Premieres and Key Early Performances

Boult's early career was marked by several significant premieres and revivals that had a lasting impact on British music. In 1918, he conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in a series of concerts featuring important new British works. Among these was the premiere of a revised version of Vaughan Williams's A London Symphony, a performance that was famously "rather spoilt by a Zeppelin raid".

His most celebrated premiere from this period was Gustav Holst's monumental suite The Planets. Boult conducted the first performance on 29 September 1918 for an invited audience of approximately 250 people. Holst, deeply appreciative of Boult's efforts, inscribed on his own copy of the score, "This copy is the property of Adrian Boult who first caused The Planets to shine in public and thereby earned the gratitude of Gustav Holst."

Edward Elgar was another composer who expressed profound gratitude to Boult. Elgar's Second Symphony had received few performances since its premiere nine years prior. When Boult conducted it at the Queen's Hall in March 1920, the performance was met with "great applause" and "frantic enthusiasm". Elgar himself wrote to Boult, stating, "With the sounds ringing in my ears I send a word of thanks for your splendid conducting of the Sym... I feel that my reputation in the future is safe in your hands." The violinist W. H. Reed, a friend and biographer of Elgar, credited Boult's performance with bringing "the grandeur and nobility of the work" to wider public attention.

Boult also took over the British Symphony Orchestra after its founder, Raymond Roze, died in March 1920. He conducted the orchestra, composed of professional musicians who had served in the Army during the First World War, in a series of concerts at the Kingsway Hall. He also led the orchestra in concerts at the People's Palace in Mile End Road, London, in 1921 and 1922, aiming to decentralize music access. His final appearance with the orchestra was at the 1923 Aberystwyth Festival.

2.3. Academic and Organizational Work

Beyond the podium, Boult made significant contributions to music education and organization. In 1921, he conducted the first season of the Robert Mayer concerts for children, although his participation in subsequent seasons was limited by other commitments.

A particularly notable contribution was his academic role at the Royal College of Music. When Hugh Allen became principal of the college, he invited Boult to establish a conducting class, modeled on the methods Boult had observed in Leipzig. This initiative, which Boult ran from 1919 to 1930, was the first such class in England and laid the groundwork for all subsequent formal training for conductors across Britain. In 1921, he was awarded a Doctorate of Music. From 1928 to 1931, he also served as conductor of The Bach Choir in London, succeeding his friend Vaughan Williams.

3. Birmingham and BBC Symphony Orchestra

Boult's career reached new heights with his appointments in Birmingham and, most notably, with the BBC, where he played a foundational role in establishing a world-class orchestra.

3.1. Birmingham City Symphony Orchestra

In 1924, Boult was appointed conductor of the Birmingham Festival Choral Society, which soon led to his becoming the musical director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO). He remained in this position for six years, gaining widespread recognition for his adventurous programming. This period marked the first time in his life that Boult had his own orchestra and, uniquely, sole control over its programming.

However, his tenure in Birmingham was not without challenges. The orchestra faced inadequate funding, and the available venues, including the Town Hall, were unsatisfactory. Furthermore, the local music critic, A. J. Symons of the Birmingham Post, was a constant source of criticism, and the concert-going public in Birmingham generally held conservative tastes. Despite this conservatism, Boult made a concerted effort to program innovative music, including works by Mahler, Stravinsky, and Bruckner. Such departures from the expected repertoire sometimes led to reduced box-office takings, necessitating subsidies from private benefactors, including Boult's own family. While in Birmingham, Boult also had the opportunity to conduct several operas, primarily with the British National Opera Company, including Die Walküre and Otello, as well as works by Purcell, Mozart, and Vaughan Williams.

3.2. BBC Symphony Orchestra

The relatively poor standards of London orchestras in the late 1920s, highlighted by visits from the Hallé Orchestra and the Berlin Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler, spurred a desire to establish a first-class symphony orchestra in Britain. Sir Thomas Beecham and Sir John Reith, the director general of the BBC, initially planned a joint venture. However, negotiations failed, and Beecham eventually formed the rival London Philharmonic Orchestra.

In 1930, Boult returned to London to succeed Percy Pitt as the BBC's director of music. Upon assuming the role, Boult and his department meticulously recruited musicians, expanding the new BBC Symphony Orchestra to 114 players. A significant portion of these musicians performed at the 1930 Promenade Concerts under Sir Henry Wood. The full BBC Symphony Orchestra gave its inaugural concert on 22 October 1930, conducted by Boult at the Queen's Hall, featuring music by Wagner, Brahms, Saint-Saëns, and Ravel. Boult conducted nine of the 21 programs in the orchestra's first season.

The new orchestra received enthusiastic reviews. The Times praised its "virtuosity" and Boult's "superb" conducting, while The Musical Times noted the "exhilaration" of the playing and confirmed the BBC's success in assembling a first-class orchestra. The Observer lauded the "altogether magnificent" playing and stated that Boult "deserves an instrument of this fine calibre to work on, and the orchestra deserves a conductor of his efficiency and insight." Following these initial successes, Reith's advisers recommended Boult as the best conductor for the orchestra. Reith offered him the chief conductorship, and Boult chose to hold both posts simultaneously, a decision he later admitted was rash but made possible by the efforts of his dedicated staff, including Edward Clark, Julian Herbage, and Kenneth Wright.

Throughout the 1930s, the BBC Symphony Orchestra gained renown for its exceptional standard of playing and Boult's adept performances of both new and unfamiliar music. Boult, much like Henry Wood before him, considered it his duty to deliver the best possible performances across a wide range of composers, even those whose works were not personally appealing to him. His biographer, Michael Kennedy, noted that there was a very short list of composers whose works Boult refused to conduct, making it difficult to discern his personal preferences from his programming.

Boult's pioneering work with the BBC included an early performance of Schoenberg's Variations, Op. 31, and British premieres such as Alban Berg's opera Wozzeck and Three Movements from the Lyric Suite. He also conducted world premieres, including Vaughan Williams's Symphony No. 4 in F minor and Bartók's Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra. He introduced Mahler's Ninth Symphony to London in 1934 and Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra in 1946. Boult also invited Anton Webern to conduct eight BBC concerts between 1931 and 1936.

The excellence of Boult's orchestra attracted leading international conductors. In its second season, guest conductors included Richard Strauss, Felix Weingartner, and Bruno Walter. Subsequent seasons featured Serge Koussevitzky, Beecham, and Willem Mengelberg. Arturo Toscanini, widely regarded as the world's foremost conductor at the time, conducted the BBC orchestra in 1935 and declared it the finest he had ever directed. Toscanini returned to conduct the orchestra in 1937, 1938, and 1939.

During this period, Boult also accepted international guest conductorships, appearing with the Vienna Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, and New York Philharmonic orchestras. In 1936 and 1937, he led successful European tours with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, performing in Brussels, Paris, Zurich, Budapest, and Vienna, where they were particularly well received. Boult also maintained contact with the world of opera, with his performances of Die Walküre at Covent Garden in 1931 and Fidelio at Sadler's Wells Theatre in 1930 being considered outstanding.

In 1933, Boult married Ann Wilson, the former wife of tenor Steuart Wilson. This marriage, which lasted for the rest of his life and saw him become a beloved stepfather to her four children, provoked lasting enmity from Steuart Wilson. Despite the social stigma attached to divorce in Britain at the time, Boult's career remained unaffected. He was invited to conduct the orchestra at Westminster Abbey for the coronation of George VI in 1937.

During the Second World War, the BBC Symphony Orchestra was evacuated, first to Bristol, where it suffered from bombing, and later to Bedford. Boult diligently worked to maintain the orchestra's standards and morale despite losing key players, with forty musicians leaving for active service or other activities between 1939 and the end of the war. In 1942, Boult resigned as the BBC's director of music, a move made to provide a suitable wartime position for the composer Arthur Bliss, though he remained chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra. This decision later contributed to his departure from the BBC. During the war, he made notable recordings of Elgar's Second Symphony, Holst's The Planets, and Vaughan Williams's Job, A Masque for Dancing. After the war, Boult found a changed attitude towards the orchestra within the BBC's upper echelons, and without Reith's support, he had to strive to restore the orchestra to its pre-war glory.

On 29 September 1946, Boult conducted Britten's new Festival Overture to inaugurate the BBC Third Programme. For this innovative cultural channel, Boult was involved in pioneering ventures, including the British premiere of Mahler's Third Symphony. The Times later commented that "The Third Programme could not possibly have had the scope which made it world-famous musically without Boult."

However, Boult's time at the BBC was drawing to a close. Despite an informal promise from Reith in 1930 that he would be exempt from the BBC's mandatory retirement age of 60, Reith's departure in 1938 meant this promise held no weight with his successors. In 1948, Steuart Wilson, Boult's former brother-in-law, was appointed head of music at the BBC. Wilson, driven by past animosity, insisted on Boult's enforced retirement as chief conductor. The director general of the BBC at the time, Sir William Haley, later acknowledged that he "had listened to ill-judged advice in retiring him." By the time of his retirement from the BBC in 1950, Boult had conducted an impressive 1,536 broadcasts.

4. London Philharmonic Orchestra

After his departure from the BBC, Boult embarked on a significant and revitalizing association with the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

4.1. Rebuilding the London Philharmonic Orchestra

When it became clear that Boult would have to leave the BBC, Thomas Russell, the managing director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO), offered him the position of principal conductor, succeeding Eduard van Beinum. The LPO, which had flourished in the 1930s, had struggled financially and artistically since Beecham's departure in 1940. Boult was already familiar with the orchestra, having been among the musicians who helped support it in 1940 by conducting fundraising concerts. He took over as chief conductor of the LPO in June 1950, immediately after leaving the BBC, and dedicated himself to its rebuilding.

In the early years of his conductorship, the LPO's finances were precarious, and Boult personally subsidized the orchestra from his own funds for some time. The pressing need for income compelled the orchestra to perform significantly more concerts than its rivals; in the 1949-50 season, the LPO gave 248 concerts, a stark contrast to the 55 by the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Although Boult had extensively worked in the studio for the BBC, he had only recorded a portion of his vast repertoire for commercial release up to this point. With the LPO, he embarked on a series of commercial recordings that continued throughout the rest of his active career. Their first joint recordings included Elgar's Falstaff, Mahler's Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with mezzo-soprano Blanche Thebom, and Beethoven's First Symphony. Reviewers widely praised the work of the new team. The Gramophone commented on the Elgar recording, "I have heard no other conductor approach [Boult's] performance... His newly adopted orchestra responds admirably." Neville Cardus in The Manchester Guardian added, "Nobody is better able than Sir Adrian Boult to expound the subtly mingled contents of this master work."

In January 1951, Boult and the LPO undertook a demanding tour of Germany, performing 12 concerts on 12 successive days. Their repertoire included symphonies by Beethoven, Haydn (the London Symphony), Brahms, Schumann, and Schubert (the Great C major), alongside other works by Elgar, Holst, Richard Strauss, and Stravinsky.

In 1952, the LPO secured a favorable five-year contract with Decca Records, which included a 10 percent commission on most sales, an unusually rewarding arrangement for the orchestra. Additionally, Boult consistently contributed his share of the recording fees to the orchestra's funds. That same year, the LPO faced a crisis when Thomas Russell, its managing director, was dismissed due to his membership in the Communist Party of Great Britain. While Boult initially supported Russell, he eventually withdrew his protection, leading to Russell's forced departure. It is speculated that Boult made this difficult decision to safeguard the orchestra's financial stability and enhance its chances of becoming the resident orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall.

In 1953, Boult once again conducted orchestral music for a coronation, leading an ensemble drawn from various UK orchestras at the coronation of Elizabeth II. During the ceremony, he conducted the first performances of Bliss's Processional and Walton's march Orb and Sceptre. He also returned to the Proms that year, conducting the LPO. The reviews were mixed, with The Times finding a Brahms symphony "rather colourless, imprecise and uninspiring" but praising the performance of The Planets. The orchestra celebrated its 21st birthday that year with a series of concerts featuring guest conductors such as Paul Kletzki, Jean Martinon, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt, Georg Solti, Walter Susskind, and Vaughan Williams.

In 1956, Boult and the LPO embarked on a tour of Russia. Boult was initially reluctant due to the discomfort of flying and long land journeys, but the Soviet authorities insisted on his leadership, compelling him to go. The LPO performed nine concerts in Moscow and four in Leningrad, with Anatole Fistoulari and George Hurst assisting as conductors. Boult's Moscow programs included Vaughan Williams's Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, Holst's The Planets, Walton's Violin Concerto (with Alfredo Campoli as soloist), and Schubert's Great C major Symphony. While in Moscow, Boult and his wife visited the Bolshoi Opera and attended composer Dmitri Shostakovich's 50th birthday party.

4.2. Later Association and Presidency

Following the Russian tour, Boult informed the LPO of his desire to step down from the principal conductorship. He continued to serve as the orchestra's main conductor until his successor, William Steinberg, assumed the post in 1959. After the sudden resignation of Andrzej Panufnik from the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO), Boult briefly returned as principal conductor of the CBSO for the 1959-60 season, which marked his last chief conductorship. However, he maintained a close association with the LPO, serving as its president and a frequent guest conductor until his retirement.

5. Later Years and Retirement

The final phase of Boult's conducting career, often referred to as his "Indian Summer," saw a remarkable resurgence of his artistic activities and widespread recognition.

5.1. "Indian Summer" and Final Recordings

After stepping down from the chief conductorship of the LPO, Boult experienced a period of reduced demand in the recording studio and concert hall for a few years. Nevertheless, he received invitations to conduct in Vienna, Amsterdam, and Boston. In 1964, he made no recordings, but the following year, 1965, marked the beginning of a significant association with Lyrita records, an independent label specializing in British music. Concurrently, he resumed recording for EMI after a six-year hiatus.

Celebrations for his eightieth birthday in 1969 further elevated his profile in the musical world. Following the death of his esteemed colleague Sir John Barbirolli in 1970, Boult was increasingly viewed as "the sole survivor of a great generation" and a living link to composers like Elgar, Vaughan Williams, and Holst. As The Guardian observed, "it was when he reached his late seventies that the final and most glorious period of his career developed." He ceased accepting overseas invitations but conducted extensively in major British cities, including the Festival and Albert Halls, commencing what is widely known as his "Indian Summer" in both the concert hall and recording studio. In 1971, he was featured in the film The Point of the Stick, where he demonstrated his conducting technique with musical examples.

During a spare recording session in August 1970, Boult recorded Brahms's Third Symphony. This recording was well received and led to a series of acclaimed recordings of works by Brahms, Wagner, Schubert, Mozart, and Beethoven. While his discography primarily highlights his British repertoire, Boult's actual repertoire was much broader. He conducted seven of Mahler's nine symphonies long before the Mahler revival of the 1960s, and he programmed Ravel's complete ballet Daphnis et Chloé and Busoni's rarely staged opera Doktor Faust in the late 1940s, and he regarded Berg's Wozzeck as a masterpiece. He expressed disappointment at rarely being invited to conduct in the opera house, and he particularly relished the opportunity to record extensive excerpts from Wagner's operas in the 1970s.

Having conducted several ballets at Covent Garden during the 1970s, Boult gave his last public performance conducting Elgar's ballet The Sanguine Fan for the London Festival Ballet at the London Coliseum on 24 June 1978. His final recording, completed in December 1978, featured music by Hubert Parry.

5.2. Retirement

Sir Adrian Boult formally retired from conducting in 1981. He passed away in London on 22 February 1983, at the age of 93, leaving his body to medical science.

6. Musicianship and Conducting Style

Boult's approach to music was characterized by a profound respect for the composer's intentions, a meticulous attention to clarity and balance, and an understated yet highly effective conducting technique.

6.1. Core Principles and Philosophy

From his earliest concerts, Boult was noted for his thorough knowledge of the works he conducted, allowing the music to "speak for itself" without resorting to showmanship. He had an "immaculate stick technique," which he had acquired early in his career, and held a quiet disdain for conductors who used excessive physical gestures to convey their artistic requirements. In an profession often marked by inflated egos and theatricality, Boult brought a rare integrity to every endeavor.

His biographer, Michael Kennedy, summarized Boult's artistry: "In the music he admired most, Boult was often a great conductor; in the rest, an extremely conscientious one." While he might have appeared unexciting or unemotional from behind, his orchestral players observed the animation in his face, and he was capable of stern outbursts of temper during rehearsals. Tall and upright, with a somewhat military bearing, he embodied the image of an English gentleman, though his sharp wit and occasional sarcasm revealed a more complex personality. Grove's Dictionary described him as the least sensational but not the least remarkable among leading British conductors of his time, emphasizing his unwavering loyalty to the composer, selflessness, and ability to grasp the music as a cohesive whole.

6.2. Repertoire and Championing British Music

Boult was widely recognized for his extensive championing of British music. He conducted the premieres of significant works such as Holst's The Planets and revised versions of Vaughan Williams's A London Symphony. He also played a crucial role in the revival and re-evaluation of Elgar's Second Symphony. His repertoire included works by Bliss, Britten, Delius, Rootham, Tippett, and Walton. While he was a staunch advocate for British composers, he was known to have a musical aversion to Delius and reportedly avoided Britten's works after Britten criticized his conducting.

Beyond British music, Boult was also a significant interpreter of core European repertoire and modern works. During his BBC years, he introduced British audiences to works by foreign composers such as Bartók, Berg, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Webern. He was particularly highly regarded for his performances of German composers like Beethoven, Brahms, and Wagner. A notable achievement was his 1966 professional orchestra premiere of Havergal Brian's monumental Symphony No. 1 "Gothic" with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, a performance that was recorded and later officially released.

Boult felt equally comfortable in the recording studio as on the concert platform, a trait that set him apart from many contemporaries who found recording without an audience uninspiring. He consistently stated that his approach remained "completely unchanged" in the studio environment.

6.3. Orchestral Balance and Sound

A hallmark of Boult's musicianship was his meticulous attention to orchestral balance. He preferred the traditional orchestral layout, with first violins positioned on the conductor's left and second violins on the right. He argued against the modern layout, which places all violins on the left, stating that while it might be "easier for the conductor and the second violins," he firmly believed that "the second violins themselves sound far better on the right." He noted that conductors like Richter, Weingartner, Walter, and Toscanini maintained this traditional balance.

Orchestral players who worked with Boult consistently commented on his insistence that every important part of the score should be clearly audible. A BBC principal violist in 1938 noted that "If a woodwind player has to complain that he has already been blowing 'fit to burst' there is trouble for somebody." Decades later, trombonist Raymond Premru echoed this, praising Boult's ability to "reduce the dynamic level - 'No, no, pianissimo, strings, let the soloist through, less from everyone else.' That is the old idea of balance."

6.4. Educational Influence

Boult's influence extended significantly into music education, impacting several generations of musicians. He established and ran the first conducting class in Britain at the Royal College of Music in London from 1919 to 1930, creating its curriculum from his own extensive experience. This class became the foundation for all subsequent formal training for conductors across Britain. In the 1930s, he also hosted a series of "conferences for conductors" at his country house near Guildford, sometimes assisted by Vaughan Williams, who lived nearby. He returned to teach at the Royal College of Music from 1962 to 1966. In his later years, he generously dedicated time to young conductors seeking his advice. Among those who studied with or were significantly influenced by Boult were Sir Colin Davis, James Loughran, Richard Hickox, and Vernon Handley, the latter of whom was not only a pupil but also served as Boult's musical assistant on numerous occasions. Other conductors who studied with him include Roger Norrington, Douglas Bostock, and Kirk Trevor.

7. Recording Career

Boult's extensive recording career spanned from the acoustic era to the dawn of digital sound, leaving behind a vast and influential discography.

7.1. Early Recordings (1920s-1940s)

In the first phase of his recording career, from 1920 to the late 1940s, Boult recorded almost exclusively for HMV/EMI. These early recordings captured his interpretations of a wide range of works, reflecting his diverse concert repertoire.

7.2. Mid-Career Recordings (1950s-early 1960s)

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Boult was less in demand by the major record labels. Although he made a substantial number of discs for Decca Records, he primarily recorded for smaller labels, most notably Pye Nixa. This period saw him continue to build his discography, albeit with less prominent labels.

7.3. Later Recordings ("Indian Summer")

His final and most prolific recording period, often referred to as his "Indian Summer," began in the mid-1960s and was once again primarily with HMV/EMI. Working regularly with producer Christopher Bishop and engineer Christopher Parker, Boult made over sixty recordings. During this time, he re-recorded much of his key repertoire in stereo, ensuring his definitive interpretations were preserved with modern sound quality. He also expanded his discography by recording many works he had not committed to disc before.

Of the British composers, Boult extensively recorded, and often re-recorded, major works by Elgar and Vaughan Williams. He recorded all eight then-existing symphonies by Vaughan Williams for Decca Records in the 1950s with the LPO, with the composer present and approving of Boult's interpretations. Vaughan Williams was scheduled to attend the first recording of his Ninth Symphony for Everest Records in 1958 but passed away the night before the session; Boult recorded a short introduction as a memorial tribute. All these recordings have been reissued on CD. In the 1960s, Boult re-recorded the nine symphonies for EMI. Other British composers prominently featured in Boult's discography include Holst, Ireland, Parry, and Walton.

Despite his reputation as a pioneer in Britain for works by the Second Viennese School and other avant-garde composers, record companies remained cautious about recording him in this repertoire. Consequently, only a single recording of a Berg piece represents this important aspect of Boult's work. In the core continental orchestral repertoire, Boult's recordings of the four symphonies of Brahms and Schubert's Great C major Symphony were celebrated during his lifetime and have remained in catalogues for decades after his death. Late in his recording career, he recorded four discs of excerpts from Wagner's operas, which received significant critical acclaim. The exceptional breadth of Boult's repertoire also resulted in well-regarded recordings of works not immediately associated with him, such as Berlioz's Ouvertures (1956), Franck's Symphony (1959), Dvořák's Cello Concerto with Mstislav Rostropovich (1958), and a pioneering live recording of Mahler's Third Symphony from 1947.

8. Honours and Memorials

Sir Adrian Boult received numerous accolades and lasting tributes throughout his distinguished career and posthumously.

8.1. Honours and Awards

Boult was knighted as a Knight Bachelor in 1937, granting him the title "Sir." In 1969, he was appointed a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH), a special award for service of national importance. He received the gold medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1944 and the Harvard Glee Club medal (jointly with Vaughan Williams) in 1956. His academic achievements were recognized with honorary degrees and fellowships from 13 universities and conservatoires. In 1951, he was invited to be the first president of the Elgar Society, and in 1959, he was made president of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music. In June 2013, Gramophone magazine inducted Boult into its Hall of Fame, acknowledging his lasting impact on recorded classical music.

8.2. Memorials

A small memorial stone to Sir Adrian Boult was unveiled in the north choir aisle of Westminster Abbey on 8 April 1984, commemorating his contributions. His old school, Westminster School, honored him by naming its music centre after him. The Royal Birmingham Conservatoire also included the Adrian Boult Hall within its home building, which was used for classical concerts, other musical performances, and conferences. However, this hall was demolished in June 2016 as part of a redevelopment project.

9. Legacy and Influence

Sir Adrian Boult's legacy extends far beyond his performances and recordings, profoundly shaping the landscape of classical music, particularly in Britain.

9.1. Influence on Future Generations of Conductors

Boult's impact on subsequent generations of conductors was significant. His pioneering conducting class at the Royal College of Music, the first of its kind in Britain, established a formal curriculum that influenced all later conductor training in the country. He also hosted "conferences for conductors" and continued to mentor young artists throughout his later life. Among those who studied with him or were deeply influenced by his principles were prominent figures such as Sir Colin Davis, James Loughran, Richard Hickox, and Vernon Handley. Handley, in particular, was not only a pupil but also served as Boult's musical assistant on many occasions, carrying forward his musical traditions. Other notable conductors who studied under Boult include Roger Norrington, Douglas Bostock, and Kirk Trevor.

9.2. Contribution to British Music

Boult's most enduring contribution to classical music was his crucial role in promoting and preserving the legacy of British composers. He was an unwavering champion of works by his friends and colleagues, including Elgar, Vaughan Williams, and Holst, ensuring their compositions reached wider audiences and gained international recognition. His commitment to premiering and reviving British works was instrumental in establishing a distinct and respected British musical identity on the world stage.

9.3. Music Education

Boult's dedication to music education was a cornerstone of his career. Through his teaching at the Royal College of Music and his mentorship of aspiring conductors, he played a vital role in nurturing new talent and fostering a deeper understanding of musical principles. His emphasis on clarity, balance, and fidelity to the composer's intentions provided a foundational approach for countless musicians, ensuring that his meticulous standards and profound musical insights continued to influence the art of conducting.

10. Writings

Beyond his conducting, Boult was also a thoughtful author and commentator on musical matters, contributing to both academic journals and publishing several books.

10.1. Books and Articles

Boult wrote numerous articles on a wide range of musical topics. These include an obituary for Nikisch published in Music and Letters (1922), an article on "Casals as Conductor" (1923), a piece on "Rosé and the Vienna Philharmonic" (1951), and an obituary for Toscanini in The Musical Times (1957).

Throughout his career, Boult also authored several books about music, though none were in print as of April 2010. His published works include:

- A Handbook on the Technique of Conducting (first published 1920, 7th edition 1951)

- The St. Matthew Passion: its preparation and performance (1949, with Walter Emery)

- Thoughts on Conducting (1963)

- My Own Trumpet (1973), his autobiography

- Boult on Music: Words from a Lifetime's Communication (1983)