1. Overview

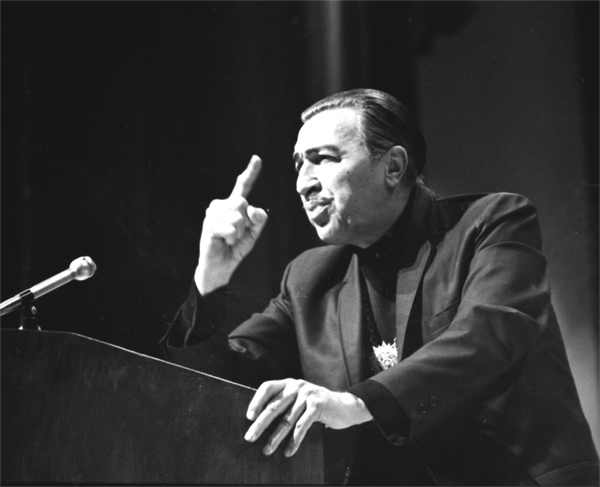

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (November 29, 1908 - April 4, 1972) was a prominent African American Baptist pastor, politician, and influential civil rights advocate. Representing the Harlem neighborhood of New York City in the United States House of Representatives from 1945 to 1971, he became the first African American elected to Congress from New York and the Northeast. Throughout his nearly three-decade tenure, Powell emerged as a powerful national figure within the Democratic Party, serving as a leading voice on civil rights and social issues. His career significantly advanced social justice and the political empowerment of African Americans, reflecting a strong commitment to progressive change. He also actively urged United States presidents to support emerging nations in Africa and Asia as they gained independence from colonialism. In 1961, Powell achieved the most powerful position held by an African American in Congress at that time, becoming chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee. In this role, he championed and oversaw the passage of crucial social and civil rights legislation under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, playing a key part in the "Great Society" initiatives. Despite his significant achievements, his later career was marked by controversies, including allegations of financial misconduct, which led to his temporary exclusion from Congress in 1967. However, he was re-elected, and the Supreme Court of the United States ultimately ruled in Powell v. McCormack (1969) that his exclusion was unconstitutional, leading to his reinstatement. He lost his seat in 1970 and subsequently retired from electoral politics.

2. Early life and education

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was born on November 29, 1908, in New Haven, Connecticut. He was the second child and only son of Adam Clayton Powell Sr. and Mattie Buster Shaffer. His parents, born into poverty in Virginia and West Virginia, respectively, were of multiracial heritage, including African and European ancestry. According to his father, his mother also had American Indian ancestry, while Powell Jr. himself stated in his autobiography Adam by Adam that his mother had partial German ancestry. Nineteenth-century censuses classified them and their ancestors as mulatto. Powell's paternal grandmother, Sally Dunning, was at least the third generation of free people of color in her family, listed as a free mulatto in the 1860 census, along with her mother, grandmother, and siblings. Sally Dunning never identified the father of Adam Clayton Powell Sr., who was born in 1865; she appeared to have named her son after her older brother, Adam Dunning. In 1867, Sally Dunning married Anthony Bush, a mulatto freedman. The family changed their surname to Powell when they moved to Kanawha County, West Virginia, as part of their new life. Adam Jr.'s mother, Mattie Buster Shaffer, was African American, with her parents having been enslaved in Virginia before being freed after the American Civil War. Powell's parents met and married in West Virginia, a destination for many freedmen seeking work in the late 19th century.

In 1908, the year of Powell Jr.'s birth, his father became the pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. Powell Sr. was a prominent Baptist minister who had worked his way out of poverty, attending Wayland Seminary, a historically black college, and pursuing postgraduate studies at Yale University and Virginia Theological Seminary. He led the Abyssinian Baptist Church through significant expansion, including fundraising and constructing an addition to accommodate the growing congregation during the Great Migration, as many African Americans moved north. The congregation eventually grew to 10,000 members.

Due to his father's achievements, Powell Jr. grew up in a wealthy household in New York City. He was born with light skin, hazel eyes, and blond hair, which allowed him to "pass" as white, although he did not exploit this racial ambiguity until college. He attended Townsend Harris High School and then studied at City College of New York before enrolling at Colgate University as a freshman. At Colgate, he briefly passed as white to avoid racial restrictions, a decision that dismayed the four other African American students there, all of whom were athletes. Encouraged by his father to become a minister, Powell became more serious about his studies at Colgate, earning his bachelor's degree in 1930. After returning to New York, he pursued graduate work and received an M.A. in religious education from Columbia University in 1931. He also became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first African-American, intercollegiate Greek-lettered fraternity. Later in life, seemingly to reinforce his black identity, Powell would sometimes state that his paternal grandparents had been born into slavery, despite his paternal grandmother having been born free.

In Harlem, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. resided on Sugar Hill at The Garrison Apartments, 435 Convent Avenue, Apartment 3, which had also been his father's home until his death in 1953.

3. Early activities and pastoral career

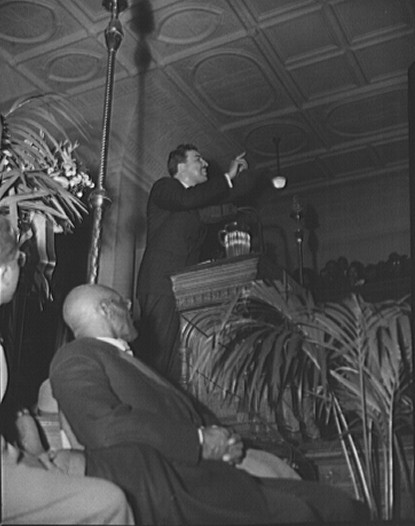

After his ordination, Powell began assisting his father with charitable services at the Abyssinian Baptist Church and as a preacher. He significantly increased the volume of meals and clothing provided to the needy, gaining a deeper understanding of the lives of the working class and poor in Harlem.

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, Powell, known for his charismatic presence, emerged as a prominent civil rights leader in Harlem. He recounted these experiences in a 1964 interview for the book Who Speaks for the Negro? He built a formidable public following by crusading for jobs and affordable housing. As chairman of the Coordinating Committee for Employment, Powell utilized various methods of community organizing to exert political pressure on major businesses, including utilities and Harlem Hospital, to open professional-level positions to black employees, rather than restricting them to the lowest-skilled jobs due to informal discrimination. He organized mass meetings, rent strikes, and public campaigns. For example, during the 1939 New York World's Fair, Powell organized a picket line at the Fair's offices in the Empire State Building, which resulted in the Fair increasing its black employees from approximately 200 to 732. In 1941, he led a successful bus boycott in Harlem, where black residents constituted the majority of passengers but held few jobs; this action compelled the New York City Transit Authority to hire 200 black workers and set a precedent for further hiring. Powell also led efforts to ensure that drugstores operating in Harlem hired black pharmacists, encouraging local residents to patronize only businesses that employed black workers. He famously stated, "Mass action is the most powerful force on earth. As long as it is within the law, it's not wrong; if the law is wrong, change the law."

On November 1, 1937, Powell succeeded his father as pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, a position he held until 1972. During his early tenure as pastor, he significantly increased the size of the congregation through sustained community outreach and inspiring sermons, while continuing his activism.

In 1942, he founded People's Voice, a newspaper aimed at a progressive African American audience. It educated readers on local events, U.S. civil rights issues, and the political and economic struggles of African peoples. Notable contributors included Powell himself, his sister-in-law and actress Fredi Washington, and journalist Marvel Cooke. The newspaper also served as a platform for his views. After his election to Congress in 1944, others took over its leadership, but it ceased publication in 1948 after facing accusations of communist connections.

4. Political career

Adam Clayton Powell Jr.'s political career began at the local level in New York City, where he quickly established himself as a voice for civil rights, before ascending to national representation in the United States Congress.

4.1. New York City Council

In 1941, Powell was elected to the New York City Council as the city's first black Council member, aided by New York City's use of the single transferable vote system. He secured 65,736 votes, achieving the third-best total among the six successful Council candidates. He served on the City Council for three years, during which he continued to advocate for the rights of African Americans.

4.2. United States House of Representatives

In 1944, Powell launched a successful campaign for the United States House of Representatives, adopting a progressive civil rights platform that focused on "fair employment practices and a ban on poll taxes and lynching." Poll taxes, along with other discriminatory practices, were used by southern states to disenfranchise most black citizens and many poor white citizens from politics, a system maintained until the 1960s. Although primarily associated with the former Confederate States of America, poll taxes were also present in some northern and western states, including California, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

Powell was elected as a Democrat, defeating Republican candidate Sara Pelham Speaks to represent the Congressional District that included Harlem. He made history as the first black Congressman elected from New York State. As historian Charles V. Hamilton noted in his 1992 political biography of Powell, he was a crucial figure in the 1940s and 1950s, often being the sole voice to "speak out" against segregation and racial injustice in Congress. Hamilton highlighted that if Powell did not raise an issue, it might not have been addressed at all. For instance, only Powell "could (or would dare to) challenge Congressman Rankin of Mississippi on the House floor in the 1940s for using the word 'nigger'." While this did not change Rankin's behavior, it provided "solace to millions who longed for a little retaliatory defiance."

Powell faced direct consequences for his outspokenness. He was banned from the White House after criticizing President Truman's wife, Bess Truman, calling her the "Last Lady of the Land." This remark came after she attended a reception for the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), an organization that had refused to allow black pianist Hazel Scott, Powell's wife at the time, to perform at the DAR Constitution Hall. Truman's attendance was perceived by Powell as an endorsement of this racist policy.

As one of only two black Congressmen until 1955 (the other being William Levi Dawson), Powell actively challenged the informal ban on black representatives using Capitol facilities previously reserved for white members. He deliberately brought black constituents to dine with him in the "Whites Only" House restaurant, often clashing with the many segregationists from the South within his own party.

Powell worked closely with Clarence Mitchell Jr., the Washington, D.C. representative of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to advocate for justice in federal programs. Biographer Hamilton described the NAACP as "the quarterback that threw the ball to Powell, who, to his credit, was more than happy to catch and run with it." Powell developed a legislative strategy known as the "Powell Amendments." This involved offering "our customary amendment" on numerous bills proposing federal expenditures, which required that federal funds be denied to any jurisdiction maintaining segregation. This tactic embarrassed liberals and angered Southern politicians. The principle of the Powell Amendments was later integrated into Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Powell also demonstrated his willingness to act independently of party lines. In 1956, he broke ranks with the Democratic Party to support President Dwight D. Eisenhower for re-election, arguing that the civil rights plank in the Democratic platform was too weak. In 1958, he successfully fended off a determined effort by the Tammany Hall Democratic Party machine in New York to remove him in the primary election. However, in 1960, Powell engaged in a controversial action when he threatened to publicly accuse Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. of having a homosexual relationship with Bayard Rustin unless planned civil rights marches at the Democratic Convention were canceled. Rustin, one of King's political advisers, was an openly gay man. King agreed to cancel the events, and Rustin subsequently resigned from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

5. Major activities and legislation

Powell's tenure in Congress was marked by significant legislative achievements and policy initiatives, particularly those aimed at advancing civil rights, social welfare, and economic justice.

5.1. Chairman of the Education and Labor Committee

In 1961, after 15 years in Congress, Powell became chairman of the powerful United States House Committee on Education and Labor. This was the most influential position held by an African American in Congress up to that point. As chairman, he presided over the passage of numerous federal social programs. His committee expanded the minimum wage to include retail workers and advocated for equal pay for women. He supported legislation for education and training for the deaf, nursing education, and vocational training. Furthermore, he led initiatives for standards concerning wages and work hours, as well as for aid to elementary and secondary education and school libraries. Powell's committee was exceptionally effective in enacting major components of President Kennedy's "New Frontier" and President Johnson's "Great Society" social programs and the War on Poverty. President Johnson, in a letter congratulating Powell on the fifth anniversary of his chairmanship on May 18, 1966, noted that the committee had successfully reported "49 pieces of bedrock legislation" to Congress.

6. International activities

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. also extended his focus to international affairs, particularly to the issues faced by developing nations in Africa and Asia, undertaking numerous trips overseas. He strongly urged presidential policymakers to pay attention to nations seeking independence from colonial powers and to provide them with aid. During the Cold War, many of these newly independent nations sought neutrality between the United States and the Soviet Union. Powell frequently delivered speeches on the House Floor to commemorate the anniversaries of the independence of countries such as Ghana, Indonesia, and Sierra Leone, highlighting their significance on the global stage.

In 1955, defying the advice of the State Department, Powell attended the Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, as an observer. His public addresses at the conference made a positive international impression, as he skillfully balanced his concerns about his own nation's race relations problems with a spirited defense of the United States against Communist criticisms. Upon his return to the United States, Powell received a warm bipartisan reception for his performance, and he was invited to meet with President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Leveraging this influence, Powell suggested to the State Department that the prevailing method of competing with the Soviet Union in the realm of fine arts, such as sponsoring international tours of symphony orchestras and ballet companies, was ineffective. Instead, he advised that the United States should concentrate on popular arts, specifically sponsoring international tours of leading jazz musicians. He argued that this approach would draw attention to an indigenous American art form and feature musicians who often performed in mixed-race bands. The State Department approved his idea, and the first such tour, featuring Dizzy Gillespie, proved to be an outstanding success abroad, prompting similarly popular tours with other musicians for many years thereafter.

7. Political controversy and legal disputes

By the mid-1960s, Adam Clayton Powell Jr.'s career became increasingly overshadowed by criticism regarding his conduct, leading to significant political and legal challenges. He faced accusations of mismanaging his committee's budget, taking trips abroad at public expense, and frequently missing committee meetings. When scrutinized by the press and fellow members of Congress for his personal conduct-including taking two young women on overseas travel at government expense-he defiantly responded, "I wish to state very emphatically... that I will always do just what every other Congressman and committee chairman has done and is doing and will do." Opponents in his district intensified their criticism, especially due to his refusal to pay a slander judgment of 150.00 K USD from 1963, which made him subject to arrest. He also spent increasing amounts of time at his retreat in Florida.

7.1. Exclusion from Congress and reinstatement

In January 1967, the House Democratic Caucus stripped Powell of his chairmanship of the Education and Labor Committee. This action followed a series of hearings on Powell's alleged misconduct held by the 89th Congress in December 1966, which produced evidence cited by the Caucus. Upon the reconvening of the 90th Congress, a Select House Committee was established by the Speaker of the House to further investigate Powell's misconduct and determine if he should be allowed to take his seat. Chaired by Emanuel Celler of New York, the committee's inquiry focused on three main issues: Powell's age, citizenship, and residency; the status of legal proceedings against him in New York State and Puerto Rico, particularly instances where he had been held in contempt of court; and allegations of official misconduct since January 3, 1961.

Hearings of the Select House Committee took place over three days in February 1967. Powell attended only on the first day, February 8. Neither he nor his legal counsel requested that the committee summon any witnesses, maintaining the official position that "the Committee had no authority to consider the misconduct charges." The select committee concluded that Powell met the constitutional residency requirements for Congressional representatives. However, it found that Powell had asserted an unconstitutional immunity from earlier rulings against him in criminal cases in the New York State Supreme Court. The committee also discovered numerous acts of financial misconduct, including the appropriation of Congressional funds for his personal use, the use of funds designated for the House Education and Labor Committee to pay the salary of a housekeeper at his property on Bimini in The Bahamas, purchasing airline tickets for himself, family, and friends with committee funds, and submitting false reports on expenditures of foreign currency while leading the committee.

The members of the Select Committee held differing opinions on the fate of Powell's seat. While Claude Pepper strongly advocated for recommending that Powell not be seated at all, John Conyers, the sole African American Representative on the committee, believed that any punishment beyond severe censure was inappropriate. Conyers argued in the committee's official report that Powell's conduct during the investigations was not contrary to the dignity of the House of Representatives and suggested that cases of misconduct brought before the House should never exceed censure. Ultimately, the Select House Committee recommended that Powell be seated but stripped of his seniority and compelled to pay a fine of 40.00 K USD. This recommendation cited Article I, Section 5, Clause 2 of the Constitution, which grants each house of Congress the authority to punish members for improper conduct.

Despite the Select Committee's recommendation, the full House initially refused to seat him until the investigation was complete. Powell urged his supporters to "keep the faith, baby" during this period. On March 1, the House voted 307 to 116 to exclude him. Powell reacted by stating, "On this day, the day of March, in my opinion, is the end of the United States of America as the land of the free and the home of the brave."

Powell subsequently won the Special Election held to fill the vacancy caused by his exclusion, securing 86% of the vote. However, he did not take his seat immediately, as he was pursuing a separate lawsuit. He sued in Powell v. McCormack to retain his seat. In November 1968, Powell was re-elected. On January 3, 1969, he was seated as a member of the 91st Congress, but he was fined 25.00 K USD and denied seniority. In June 1969, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Powell v. McCormack that the House had acted unconstitutionally when it excluded Powell, as he had been duly elected by his constituents.

Despite his legal victory, Powell's increasing absenteeism was noted by his constituents. This contributed to his defeat in the Democratic primary for re-election in June 1970, when he was challenged and ultimately surpassed by Charles B. Rangel. Powell failed to gather enough signatures to appear on the November ballot as an Independent, and Rangel went on to win that general election and subsequent ones. In the fall of 1970, Powell moved to his retreat on Bimini in The Bahamas, and also resigned as minister at the Abyssinian Baptist Church.

8. Personal life and family

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was married three times. In 1933, he married Isabel Washington (1908-2007), an African American singer and nightclub entertainer and the sister of actress Fredi Washington. Powell adopted Washington's son, Preston, from her first marriage.

After their divorce, Powell married the renowned jazz pianist and singer Hazel Scott in 1945. They had one son, Adam Clayton Powell III, born in 1946. In the early 21st century, Adam Clayton Powell III became Vice Provost for Globalization at the University of Southern California.

Powell divorced again, and in 1960, he married Yvette Flores Diago from Puerto Rico. They had a son, whom they named Adam Clayton Powell Diago, incorporating his mother's surname as a second surname in accordance with Hispanic tradition. In 1980, this son changed his name to Adam Clayton Powell IV, dropping "Diago" from his name when he moved to the mainland United States from Puerto Rico to attend Howard University. Adam Clayton Powell IV, also known as A. C. Powell IV, followed in his father's footsteps, being elected to the New York City Council in 1991 in a special election, serving two terms. He also served as a New York state Assemblyman for East Harlem for three terms and had a son named Adam Clayton Powell V. In both 1994 and 2010, Adam Clayton Powell IV unsuccessfully challenged incumbent Rep. Charles B. Rangel for the Democratic nomination in his father's former congressional district.

8.1. Family scandal

In 1967, a U.S. Congressional committee subpoenaed Yvette Diago, Powell Jr.'s former third wife and the mother of Adam Clayton Powell IV, as part of an investigation into potential "theft of state funds." The inquiry focused on allegations that she had been on Powell Jr.'s Congressional payroll without performing any work. Yvette Diago admitted to the committee that she had been on her former husband's Congressional payroll from 1961 until 1967, despite having moved back to Puerto Rico in 1961. As reported by Time magazine, Yvette Diago continued to live in Puerto Rico and "performed no work at all," yet remained on the payroll. Her salary was increased to 20.58 K USD, and she was paid until January 1967, when the situation was exposed, and she was subsequently fired.

9. Death

In April 1972, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. became gravely ill and was flown to a Miami hospital from his home in Bimini. He died there on April 4, 1972, at the age of 63. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, the cause of death was acute prostatitis. His funeral was held at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Following the service, his son, Adam Clayton Powell III, scattered his ashes from a plane over the waters of Bimini, fulfilling his father's wishes.

10. Legacy and assessment

Adam Clayton Powell Jr.'s legacy is complex, marked by both groundbreaking achievements in civil rights and political controversies. He is remembered as a pioneering figure who significantly advanced the cause of social justice and the political empowerment of African Americans, while also facing criticism for his conduct and financial dealings.

10.1. Positive assessment

Powell's pioneering role in the civil rights movement and his advocacy for the marginalized are widely recognized. His lasting contributions to social justice and the political empowerment of African Americans are evident in several ways. Seventh Avenue north of Central Park through Harlem has been renamed as Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard in his honor. A prominent landmark along this street is the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building, which was named for Powell in 1983. Additionally, two New York City schools were named after him: PS 153, located at 1750 Amsterdam Ave., and a middle school, IS 172 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. School of Social Justice, at 509 W. 129th St., though the latter closed in 2009. In 2011, the new Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Paideia Academy opened in Chicago's South Shore neighborhood, further cementing his name in educational institutions.

10.2. Criticism and controversy

Despite his significant achievements, Powell's career was not without criticism and controversy, particularly concerning his conduct, financial dealings, and personal life. The investigations into his alleged misconduct have been cited as a key impetus for the establishment of a permanent ethics committee in the United States House of Representatives and the development of a permanent code of conduct for House Members and their staff. These controversies highlight the challenges and ethical questions that arose during his public career, offering an objective view of the complexities associated with his legacy.

11. Representation in other media

The life and career of Adam Clayton Powell Jr. have been depicted and analyzed in various forms of media:

- He was the subject of the 2002 cable television film Keep the Faith, Baby, starring Harry Lennix as Powell and Vanessa Williams as his second wife, jazz pianist Hazel Scott. The film debuted on February 17, 2002, on the premium cable network Showtime. It received three NAACP Image Award nominations for Outstanding Television Movie, Outstanding Actor in a Television Movie (Lennix), and Outstanding Actress in a TV Movie (Williams). It also won two National Association of Minorities in Cable (NAMIC) Vision Awards for Best Drama and Best Actor in a Television Film (Lennix), the International Press Association's Best Actress in a Television Film Award (Williams), and Reel.com's Best Actor in a Television Film (Lennix). The film was produced by Geoffrey L. Garfield, Monty Ross, Adam Clayton Powell III, and Harry J. Ufland, and was written by Art Washington and directed by Doug McHenry.

- Powell is portrayed by Giancarlo Esposito in the 2019 Epix cable series Godfather of Harlem.

- He is featured in Paul Deo's 2017 Harlem mural Planet Harlem.

- Jeffrey Wright portrayed Powell in the 2023 Netflix film Rustin. In the film, the Powell character gradually develops a more positive view of the controversial Bayard Rustin character, who is initially portrayed as a rival during the planning of the March on Washington.

- Powell is referenced in the Vic Chesnutt song Woodrow Wilson.

12. Works

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was also an author, contributing several notable works:

- (1945) Marching Blacks, An Interpretive History of the Rise of the Black Common Man

- (1962) The New Image in Education: A Prospectus for the Future by the Chairman of the Committee on Education and Labor

- (1967) Keep the Faith, Baby!

- (1971) Adam by Adam: The Autobiography of Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

13. Electoral history

| Election Year | Position | Term | Party | Vote Percentage | Votes | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | City Councilman (Manhattan large constituency) | 165th | Democratic | 10.33% | 45,568 | 3rd | Won |

| 1944 | U.S. Representative (New York's 22nd congressional district) | 79th | Democratic | 100.00% | 83,140 | 1st | Won |

| 1946 | U.S. Representative (New York's 22nd congressional district) | 80th | Democratic | 62.54% | 32,573 | 1st | Won |

| 1948 | U.S. Representative (New York's 22nd congressional district) | 81st | Democratic | 76.43% | 63,523 | 1st | Won |

| 1950 | U.S. Representative (New York's 22nd congressional district) | 82nd | Democratic | 63.49% | 35,233 | 1st | Won |

| 1952 | U.S. Representative (New York's 16th congressional district) | 83rd | Democratic | 74.69% | 75,562 | 1st | Won |

| 1954 | U.S. Representative (New York's 16th congressional district) | 84th | Democratic | 77.55% | 43,545 | 1st | Won |

| 1956 | U.S. Representative (New York's 16th congressional district) | 85th | Democratic | 69.73% | 59,339 | 1st | Won |

| 1958 | U.S. Representative (New York's 16th congressional district) | 86th | Democratic | 90.81% | 56,383 | 1st | Won |

| 1960 | U.S. Representative (New York's 16th congressional district) | 87th | Democratic | 71.59% | 59,957 | 1st | Won |

| 1962 | U.S. Representative (New York's 18th congressional district) | 88th | Democratic | 69.65% | 59,125 | 1st | Won |

| 1964 | U.S. Representative (New York's 18th congressional district) | 89th | Democratic | 84.63% | 94,222 | 1st | Won |

| 1966 | U.S. Representative (New York's 18th congressional district) | 90th | Democratic | 74.05% | 45,308 | 1st | Won |

| 1967 | U.S. Representative (New York's 18th congressional district) | 90th | Democratic | 86.34% | 27,963 | 1st | Won |

| 1968 | U.S. Representative (New York's 18th congressional district) | 91st | Democratic | 80.77% | 37,146 | 1st | Won |