1. Overview

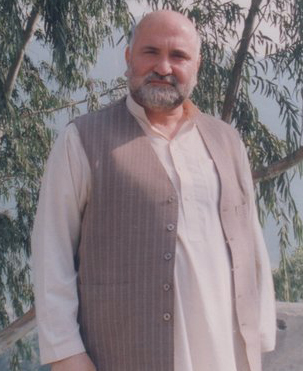

Abdul Haq (born Humayoun ArsalaHumayoun ArsalaPushto; April 23, 1958 - October 26, 2001) was a prominent Afghan mujahideen commander and politician who played a crucial role in the Soviet-Afghan War against the Soviet-backed People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Known for his effective leadership in the Kabul region, he gained significant influence across Afghanistan. Following the Soviet withdrawal, he briefly served as Interior Minister in the post-communist government but resigned due to disagreements over power-sharing and the conduct of some field commanders. Later, he became a United Nations Peace Mediator, dedicating himself to fostering reconciliation. Abdul Haq was a strong advocate for a broad-based, inclusive government in Afghanistan, actively working to unite diverse ethnic groups against the Taliban regime. In October 2001, he attempted to incite a popular uprising against the Taliban but was captured and executed, becoming a martyr for his cause. His legacy is marked by his unwavering commitment to Afghan self-determination and his vision for a unified, democratic Afghanistan, though his later efforts were met with both praise for his unifying potential and criticism regarding his effectiveness by some external actors.

2. Early life and background

Abdul Haq was born as Humayoun Arsala in Seydan, a small village in Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan. His early life was marked by a move with his family to Helmand Province, where his father, Mohammed Aman, worked as a representative for a Nangarhar construction company, making the family relatively wealthy by Afghan standards.

2.1. Childhood and education

Haq began school at the early age of five, reportedly an unruly child who once hit a sleeping teacher. A year later, his 51-year-old father died of kidney disease, leading his older brother, Haji Din Mohammad, to assume family leadership and prompting their return to their extended family in Nangarhar. Back in Fatehabad, Haq attended a madrasah under local mullahs before studying at the Lycée from the age of eight. It was during this period that he began to challenge the Communist ideology espoused by some of his teachers. He was fluent in PashtoPushto, DariDariPersian, and English.

2.2. Family and lineage

Haq's family was well-connected, belonging to the Arsala Khel family, a part of the Jabar Khel, which is a subtribe of the land-owning Ahmadzai tribe, all of whom are Pashtuns. His paternal great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Afghanistan's foreign minister in 1869, actively engaging in policies concerning Britain and Russia. His cousin, Hedayat Arsala, was a World Bank director in Washington, D.C. who later became Vice President of Afghanistan in Hamid Karzai's administration (December 2001 - December 2004). Abdul Haq had two older brothers, Haji Din Mohammad and Abdul Qadir, and a younger brother, Nasrullah Baryalai Arsalai. Abdul Qadir, an early supporter of Hamid Karzai, was appointed to a cabinet position before his assassination in 2002. Haji Din Mohammad is the leader of the Hezb-e Islami Khalis party.

3. Mujahideen years

Abdul Haq's involvement in the armed struggle against the Soviet-backed Afghan government began in 1978, initially without external support. He quickly rose through the ranks, becoming one of the most renowned and influential field commanders operating in Kabul Province.

3.1. Soviet-Afghan War participation

Haq joined the Hezb-e Islami Khalis faction led by Mohammad Yunus Khalis, distinguishing it from the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin faction of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. During the Soviet-Afghan War, he coordinated Mujahideen activities in the province of Kabul, earning a reputation for his battlefield prowess and leadership. He was dispatched abroad several times as a diplomat, and it is said that President Ronald Reagan's decision to provide large-scale military aid to the Mujahideen was due to his persuasion. He defended the use of long-range rockets against Kabul, despite civilian casualties, stating, "I have to free my country. My advice to people is not to stay close to the government. If you do, it's your fault. We use poor rockets; we cannot control them. They sometimes miss. I don't care about people who live close to the Soviet Embassy, I feel sorry for them, but what can [I] do?"

3.2. Factions and alliances

Haq's primary affiliation was with the Hezb-e Islami Khalis faction, under Mohammad Yunus Khalis. His strategic command and success in various battles elevated his standing, making him a leading figure across Afghanistan.

3.3. Role in Kabul and combat experience

His operational activities were particularly focused on the Kabul region. Abdul Haq was injured multiple times during combat, reportedly sustaining twelve injuries, including losing part of his right heel. Due to his injuries, he often fought battles against the Soviets on horseback. He also traveled to Japan for treatment for his war wounds.

3.4. Relations with the CIA and ISI

Abdul Haq was one of the CIA's earliest Afghan contacts during the initial years of the Soviet-Afghan War, becoming a crucial guide for CIA official Howard Hart in the anti-Soviet conflict. However, as the 1980s progressed, he grew critical of Pakistan's ISI and, later, the CIA, after his relationship with them deteriorated. The CIA internally labeled him "Hollywood Haq," a moniker that suggested a perception of him being more performative than effective in their eyes.

4. Post-war activities

Following the withdrawal of Soviet forces and the collapse of the communist regime, Abdul Haq transitioned from a wartime commander to a political figure, engaging in efforts to stabilize Afghanistan and later pursuing peace initiatives from exile.

4.1. Government service and resignation

In the late 1980s, he advised the US State Department during the Geneva negotiations on Soviet troop withdrawal. After the fall of the communist Najibullah regime in April 1992, Abdul Haq was appointed as the cabinet minister for internal security in the Islamic State of Afghanistan, which was established through the Peshawar Accord, a peace and power-sharing agreement. However, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who had been offered the position of prime minister, refused to share power and initiated a massive bombardment campaign against the capital, Kabul, leading to a prolonged conflict. Abdul Haq resigned as Interior Minister after only four days, criticizing some field commanders for their conduct and strongly opposing cooperation with former communist figures like Abdul Rashid Dostum.

4.2. Life in exile and business

Shortly after his resignation, Abdul Haq left Afghanistan and settled in Dubai, where he reportedly became a successful merchant.

4.3. United Nations Peace Mediator

In 1998, Abdul Haq took on a new role as a United Nations Peace Mediator, demonstrating his continued commitment to finding a resolution for the ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan.

4.4. Family tragedy

In January 1999, a tragic incident occurred at his home in Hayatabad in Peshawar, Pakistan. Unknown assailants killed his watchman, entered his residence, and murdered his wife and son. Another of Haq's sons survived the attack.

5. Anti-Taliban efforts and alliances

Abdul Haq was deeply committed to opposing the Taliban regime and dedicated his efforts to forging a unified front against their rule, emphasizing the need for broad Afghan consensus across ethnic lines.

5.1. Efforts to unite anti-Taliban forces

From 1999 onwards, Abdul Haq, alongside Ahmad Shah Massoud, initiated a process to unite various ethnic groups against the Taliban regime. While Massoud focused on uniting Tajiks, Hazara, and Uzbeks, Haq concentrated on building support among Pashtun tribal leaders. He became a key point of reference for Pashtuns, and an increasing number of Pashtun Taliban members secretly approached him, indicating a growing disillusionment with the Taliban even among their own ethnic base. Some commanders within the Taliban military apparatus agreed to their plan to topple the regime. The goal was to establish a new order, potentially with the involvement of the Haqqani network and senior Taliban figures.

5.2. Collaboration with the Northern Alliance

Senior diplomat and Afghanistan expert Peter Tomsen envisioned Abdul Haq, known as the "Lion of Kabul," and Ahmad Shah Massoud, the "Lion of Panjshir," forming a formidable anti-Taliban team if they combined forces. Tomsen believed that Haq, Massoud, and Hamid Karzai, whom he considered Afghanistan's three leading moderates, could bridge the Pashtun-non-Pashtun, north-south divide. Senior Hazara and Uzbek leaders, along with Hamid Karzai, actively participated in this unification process, agreeing to work under the banner of the exiled Afghan King, Mohammed Zahir Shah, who resided in Rome, Italy.

5.3. Planning for a post-Taliban government

In November 2000, leaders from all ethnic groups, traveling from various parts of Afghanistan, Europe, the United States, Pakistan, and India, convened at Massoud's headquarters in northern Afghanistan. The discussions focused on convening a Loya Jirga (grand assembly) to resolve Afghanistan's problems and establish a post-Taliban government. By September 2001, an international official who met with representatives of this alliance noted, "It's crazy that you have this today... Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Hazara... They were all ready to buy in to the process," highlighting the broad consensus achieved among diverse Afghan factions for a new, inclusive political order.

6. Death

Abdul Haq's final mission in October 2001 was a daring attempt to spark an internal uprising against the Taliban, which ultimately led to his capture and execution.

6.1. Infiltration and capture

Following the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, Abdul Haq entered Nangarhar Province from Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, intending to implement his resistance plan against the Taliban. While some sources speculated about CIA support for this initiative, his family members and other witnesses denied this, asserting that CIA officials, acting on the recommendation of Bud McFarlane, had actually urged him not to enter Afghanistan after assessing his capabilities. After a pursuit, Abdul Haq and nineteen companions were captured by the Taliban between the towns of Hisarak and Azro in Nangarhar province.

6.2. Execution by the Taliban

Abdul Haq was killed by the Taliban on October 26, 2001. His capture and execution were considered a significant victory by the Taliban.

6.3. Controversies and criticisms surrounding his death

The circumstances of Abdul Haq's death sparked considerable controversy and criticism. Some reports speculated that his capture was due to betrayal by double agents. Soon after his death, the CIA faced accusations of siding too closely with Pakistan's ISI, which was perceived as not wanting to see Afghans united across ethnic lines, and for failing to intervene to rescue him from his Taliban captors. This narrative was reinforced by reports of tension between Haq and American agents, particularly after an interview in which he stated, "we cannot be [America's] puppet." He was among several Afghan rebel leaders who expressed reservations about the U.S. intervention and its potential impact on Afghan self-determination.

7. Legacy and assessment

Abdul Haq's legacy in Afghan history is complex, marked by his courageous leadership during the Soviet-Afghan War and his later efforts to unite Afghanistan against the Taliban, reflecting a commitment to a broad-based, democratic future for his country.

7.1. Positive assessments of his leadership and contributions

Abdul Haq is remembered as an astute leader who played a pivotal role in the Afghan resistance against the Soviet Union. His ability to coordinate Mujahideen activities in the crucial Kabul region earned him widespread recognition. Later in his life, particularly during his anti-Taliban efforts, he was seen as a unifying figure. An obituary in The Guardian described him as "one of the few leaders capable of leading a pan-ethnic Loya Jirga" for Afghanistan, highlighting his vision for a national consensus government that transcended tribal and ethnic divides. This perspective emphasizes his commitment to Afghan self-determination and his efforts to build a truly representative post-Taliban government.

7.2. Criticisms and controversies

Despite his significant contributions, Abdul Haq's career was not without its criticisms and controversies, particularly concerning his later activities and interactions with foreign intelligence agencies.

7.2.1. "Hollywood Haq" criticism

Within the CIA, particularly among agents involved in Afghan operations after the September 11 attacks, Abdul Haq was sometimes derisively referred to as "Hollywood Haq." According to Gary Schroen, a former CIA Near East Division officer involved in Afghan operations, this moniker reflected a perception that in his later years, Haq tended to be more vocal and performative than actively engaged in on-the-ground operations. This criticism suggested that he was perceived as more interested in public image or grand pronouncements than in effective, practical action, contrasting with his earlier reputation as a formidable field commander.