1. Early life and accession to the throne

Valdemar IV's early life was marked by the turmoil of Denmark's decline, culminating in his years in exile, which undoubtedly shaped his ambition to restore the Danish monarchy. His accession to the throne was a direct response to a vacuum of power, orchestrated by key figures who sought to reclaim Denmark's sovereignty.

1.1. Childhood and exile

Valdemar was the youngest son of King Christopher II of Denmark and Euphemia of Pomerania. He belonged to the House of Estridsen. Much of his childhood and youth were spent in exile at the court of Emperor Louis IV in Bavaria. This exile was a consequence of his father's military defeats and the unfortunate fates of his two older brothers, Eric and Otto, who were either killed or imprisoned by the Holsteiners. During these formative years, Valdemar existed as a pretender, observing the political landscape and awaiting an opportunity for his return to Denmark.

1.2. Accession to the throne

The opportunity for Valdemar's return arose following the assassination of Gerhard III, Count of Holstein-Rendsburg, a powerful figure who had effectively controlled significant parts of Denmark. Niels Ebbesen, a Danish nobleman and patriot, led a national assembly, known as the Viborg Assembly (landsting), on St. John's Day, June 24, 1340. At this assembly, Valdemar was proclaimed King of Denmark. His marriage to Helvig of Schleswig, the daughter of Eric II, Duke of Schleswig, was a crucial political alliance that, along with his inheritance from his father, granted him control over approximately one-quarter of Jutland north of the Kongeå river. Unlike his father, Valdemar was not compelled to sign a royal charter upon his accession. This was likely due to Denmark having been without a king for several years, leading the powerful nobles to underestimate the young, twenty-year-old monarch, expecting him to pose no greater challenge than his father. However, Valdemar proved to be a clever and determined leader who understood that true rule of Denmark necessitated full control over its fragmented territories. Niels Ebbesen, in a separate attempt to liberate central Jutland from the Holsteiners, tragically perished with his men during the siege of Sønderborg Castle on November 2, 1340, when they were surrounded and killed by German forces.

2. Reign and reunification of Denmark

Valdemar IV's reign was characterized by relentless efforts to restore Denmark's territorial integrity and royal authority, involving shrewd financial management, military campaigns, and administrative reforms. These endeavors were set against the backdrop of the devastating Black Death and continuous internal resistance from a wary nobility.

2.1. Efforts to reclaim and unite territories

Upon his accession, Valdemar faced a Denmark that was largely bankrupt and had been extensively mortgaged in various parcels. His primary objective was to repay these debts and reclaim lost Danish lands. His first opportunity came through his wife Helvig's dowry. He then systematically paid off the mortgage on the remainder of northern Jutland using taxes collected from peasants north of the Kongeå river. In 1344, he successfully recovered North Friesland, which he immediately taxed to generate the 7,000 silver marks needed to clear the debt on southern Jutland. These continuous and heavy tax demands, however, caused considerable unrest among the peasants.

Valdemar then turned his attention to Zealand. The Bishop of Roskilde, who held control of Copenhagen Castle and the town, transferred them to Valdemar. This provided the king with a strategic and secure base from which to collect crucial taxes on trade passing through the Øresund (The Sound). This made Valdemar the first Danish king to rule from Copenhagen. He continued to acquire other castles and fortresses through capture or purchase, gradually forcing the Holsteiners out of Danish territories. When funds ran low, he resorted to military force, attempting to seize Kalundborg and Søborg Castles. During this campaign, he traveled to Estonia to negotiate with the Teutonic Knights, who controlled Danish Estonia. As Danes had never settled there in significant numbers, Valdemar decided to sell Danish Estonia for 19,000 marks, using the proceeds to pay off mortgages on more strategically vital parts of Denmark.

Around 1346, Valdemar initiated a crusade against Lithuania. The Franciscan chronicler Detmar von Lübeck recorded that Valdemar traveled to Lübeck in 1346, then proceeded to Prussia alongside Eric II of Saxony with the intent to fight the Lithuanians. However, this crusade ultimately did not materialize. Instead, Valdemar undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem without prior Papal permission, a feat for which he was honored as a Knight of the Holy Sepulchre. This unauthorized journey, however, led to his censure by Pope Clement VI.

Upon his return, Valdemar assembled a new army. In 1346, he recaptured Vordingborg Castle, a critical stronghold of the Holsteiners. By the end of that year, Valdemar could assert his claim over all of Zealand. He established Vordingborg as his personal residence, significantly expanding the castle and constructing the distinctive Goose Tower, which remains a symbol of the town to this day. Valdemar's reputation for ruthlessness against his opponents instilled fear, making many think twice before siding against him. His stringent tax policies further oppressed the peasantry, leaving them little choice but to comply. By 1347, Valdemar had largely expelled the German forces, effectively restoring Denmark as a unified nation. With his increased income, Valdemar was able to fund a larger army. Through strategic maneuvering, including acts of treachery, he gained possession of Nyborg Castle, the eastern part of Funen Island, and other smaller islands. As Valdemar's attention began to shift towards Scania, which was then under Swedish rule, a catastrophic event swept across the entire region.

2.2. Financial and administrative policies

Valdemar IV implemented various financial and administrative policies to rebuild the state's economy and strengthen royal power. He initially focused on clearing Denmark's substantial debts by taxing peasants and using the dowry from his marriage. For instance, the mortgage on northern Jutland was paid off through peasant taxes, and the recovery of North Friesland in 1344 was immediately followed by heavy taxation to secure 7,000 silver marks for the debt on southern Jutland. While these measures were effective in debt repayment, they often led to significant discontent and unrest among the over-taxed peasantry.

His establishment of Copenhagen as a ruling base was strategically important. The transfer of Copenhagen Castle and town from the Bishop of Roskilde provided Valdemar with a secure location from which to levy taxes on the lucrative trade passing through the Øresund. This made him the first Danish king to rule directly from Copenhagen. He also made Vordingborg his personal residence, expanding its castle and constructing the iconic Goose Tower, which underscored his reasserted royal authority.

Valdemar's administrative reforms aimed at centralizing power. He expanded the king's authority, relying on his military prowess and a loyal core of nobility, which would lay the groundwork for Danish rulers until 1440. To achieve this, he appointed many foreigners as court officials and councilors, circumventing the traditional Danish nobility. The most prominent among these was the German-Slavic nobleman Henning Podebusk, who served as his drost (prime minister) from 1365 to 1388, playing a critical role in Valdemar's administration and foreign relations. His tax policies, however, were notably harsh, crushing the peasantry and often leaving them in fear, with little choice but to pay.

2.3. Impact of the Black Death

The Black Death, a devastating pandemic, reached Denmark in 1349. Tradition states that the bubonic plague arrived on a "ghost ship" that beached itself on the coast of northern Jutland. Those who boarded found the deceased with swollen, black faces but still plundered valuables, thereby introducing the disease-carrying fleas into the population. Over the next two years (1349-1350), the plague spread throughout Denmark like a wildfire, causing immense loss of life. In the diocese of Ribe, for example, twelve parishes ceased to exist. Some smaller towns were completely depopulated. Overall, the plague is estimated to have decimated between 33% and 66% of Denmark's population. City dwellers were often more severely affected than those in rural areas, leading many to abandon towns entirely.

Remarkably, Valdemar IV himself remained untouched by the plague. He astutely took advantage of the crisis, particularly the deaths of many of his enemies among the nobility and the decline in noble income, to expand his royal lands and properties. Despite the severe population decline and fewer peasants working less land, Valdemar refused to reduce taxes in the following year. This decision further burdened both the surviving peasants and the nobility, whose incomes had already shrunk. The disproportionate impact of the Black Death and Valdemar's exploitative tax policies contributed to a series of widespread uprisings that flared up in the subsequent years.

2.4. Relations with the nobility and internal resistance

Valdemar IV's reign was marked by a contentious relationship with the Danish nobility, who resisted his centralized rule and continuous efforts to restore royal authority at their expense. In 1354, the King and nobles convened the Danish Court (Danehof) to negotiate a peace settlement. The resulting charter stipulated that the Danehof was to meet at least once a year on St. John's Day (June 24). It also reinstated the old system established in 1282, effectively restoring the traditional rights of the nobility that had been diminished by King Christopher II's charter.

However, Valdemar soon demonstrated his disregard for the terms of this charter. He responded to continued resistance by raising an army and marching through southern Jutland, seizing more lands that German counts had previously taken from Denmark. Rebellions quickly spread, notably in Funen, where Valdemar ravaged the remaining territories held by the Holsteiners and took control of the rest of the island. The charter proved to be largely ineffective as the king consistently ignored its provisions, leading to sporadic but persistent rebellions. A severe monetary crisis in the same year further exacerbated the widespread discontent across northern Europe.

A particularly significant instance of resistance occurred in 1358 when Valdemar attempted to reconcile with Niels Bugge (c. 1300-c. 1358), a prominent Jutland leader, along with several other nobles and two bishops. The king refused to meet their demands, prompting the group to leave the meeting in disgust. As they reached the town of Middelfart to find a ship to cross to Jutland, the fishermen they hired brutally murdered them. Valdemar IV was widely blamed for these assassinations, which ignited open rebellion in Jutland once again. The rebels agreed to support each other in their fight to restore the rights that the king had repeatedly abrogated.

Throughout his reign, Valdemar's heavy-handed methods, relentless taxation, and his usurpation of rights long held by noble families fueled continuous uprisings. While his initial attempts to re-establish Denmark as a formidable power in Northern Europe were welcomed by some Danes, his centralizing policies faced bitter opposition from the great landed families, particularly in Jutland, who saw their traditional privileges eroded.

3. Foreign policy

Valdemar IV's foreign policy was largely driven by his ambition to reassert Danish dominance in the Baltic Sea region, leading to significant conflicts with powerful neighboring entities such as the Hanseatic League and involvements in Nordic succession disputes.

3.1. Conflicts with the Hanseatic League

Valdemar recognized the growing power of the Hanseatic League, which had become a dominant force in the Baltic region. Even before the conclusion of his conflict with King Magnus of Sweden, Valdemar decided to launch an attack on the Swedish island of Gotland, specifically targeting the wealthy Hanseatic city of Visby. In 1361, he raised an army, embarked them on ships, and invaded Gotland. Valdemar's forces engaged and defeated the Gotlanders in front of the city, resulting in the deaths of 1,800 men. The city of Visby subsequently surrendered. Valdemar famously tore down a section of the city wall to make his grand entry. Once in possession, he demanded an enormous ransom: three large beer barrels had to be filled with silver and gold within three days, failing which his men would be unleashed to pillage the town. To Valdemar's surprise, the barrels were filled before nightfall on the first day, with churches being stripped of their valuables to meet the demand. The riches were then loaded onto Danish ships and transported to Vordingborg, Valdemar's residence. Following this conquest, Valdemar added "King of Gotland" to his list of titles. However, this aggressive action against Visby, a prominent member of the Hanseatic League, would have severe consequences later on.

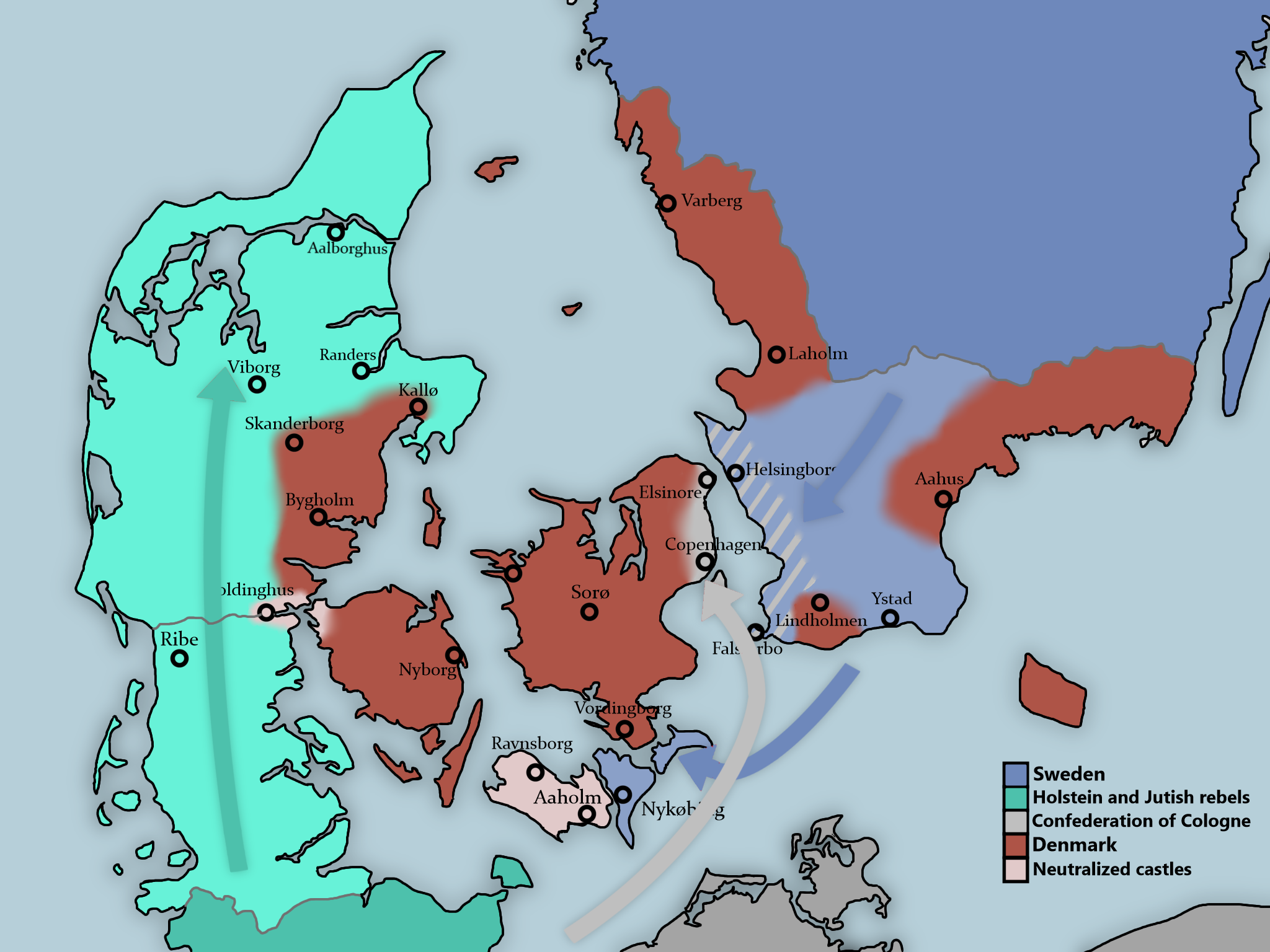

Valdemar's actions, particularly his attempts to control the lucrative herring trade in the Øresund and to assert Danish dominance over Baltic Sea trade, provoked strong reactions from the Hansa states. In 1362, the Hanseatic League, alongside Sweden and Norway, formed a powerful alliance against Valdemar, seeking retribution for his perceived threats to their economic interests. The Hanseatic fleet launched a devastating attack, ravaging the coasts of Denmark, successfully capturing and pillaging Copenhagen and parts of Scania. This foreign invasion, combined with the ongoing rebellions of nobles in Jutland, forced Valdemar to flee Denmark at Easter in 1368.

3.2. Interventions in Sweden and Norway

Valdemar IV actively sought to influence the succession in Sweden and maintain Danish influence in Nordic affairs. He intervened by capturing Countess Elizabeth of Holstein, who was betrothed to Crown Prince Håkon of Sweden. Valdemar coerced Elizabeth into a nunnery, thereby breaking the engagement. He then convinced King Magnus IV of Sweden (Håkon's father) that Håkon should marry Valdemar's own daughter, Margrethe. While King Magnus agreed to this marriage alliance, the Swedish nobles vehemently opposed it and ultimately forced Magnus to abdicate.

In Magnus's place, the nobles elected Albrecht of Mecklenburg as King of Sweden. Albrecht, a sworn enemy of Valdemar, immediately set out to thwart Valdemar's ambitions. He successfully persuaded the Hanseatic states to align with him, emphasizing Valdemar's threat to their access through the Sound and to the lucrative herring trade.

Valdemar's involvement in Sweden also stemmed from earlier events. In 1355, Prince Eric XII had rebelled against his father, King Magnus IV, seizing Scania and other parts of Sweden. King Magnus then turned to Valdemar, entering into an agreement for assistance against his rebellious son. However, Prince Eric unexpectedly died in 1359. Valdemar seized this opportunity, crossing the Sound with an army and compelling Magnus to relinquish Helsingborg in 1360. By taking Helsingborg, Valdemar effectively regained control over Scania. Since Magnus was no longer strong enough to hold Scania, it reverted to Danish control. Valdemar further expanded his territory, capturing Halland and Blekinge in addition to Scania.

Valdemar also formed strategic alliances with Poland against the Teutonic Knights, renewing this alliance in both 1350 and 1363, indicating his broader engagement in eastern Baltic politics.

3.3. Treaty of Stralsund

Following his forced exile from Denmark in 1368, Valdemar IV appointed his trusted friend and advisor, Henning Podebusk, to negotiate with the powerful Hanseatic League on his behalf. The negotiations resulted in a truce, contingent on Valdemar acknowledging the Hanseatic League's fundamental right to free trade and fishing in the strategically important Øresund Sound. As part of the agreement, the Hanseatic League gained control over several towns on the coast of Scania, along with the crucial fortress at Helsingborg, for a period of 15 years. Furthermore, they compelled the king to grant the Hanseatic League a significant say in Denmark's succession after Valdemar's death, a highly unusual and impactful concession.

Valdemar was ultimately compelled to sign the Treaty of Stralsund in 1370. This treaty formalized the acknowledgement of the Hanseatic League's rights to participate in the lucrative herring trade and granted their trading fleet extensive tax exemptions. Despite these significant concessions, the treaty allowed Valdemar to return to Denmark after an absence of four years. Crucially, even in this position of defeat, Valdemar managed to salvage something for himself and Denmark by regaining full sovereignty over Gotland, which had been a key point of contention and a source of conflict with the Hanseatic League.

4. Personal life

Beyond his political and military endeavors, Valdemar IV's personal life played a role in shaping his reign and subsequent historical narratives.

4.1. Marriage and family

In the 1330s, Valdemar IV formed an alliance with Valdemar III of Denmark, then Duke of Schleswig, against their mutual uncle, Gerhard III, Count of Holstein-Rendsburg. This alliance led to the arrangement of a marriage between Valdemar IV and Valdemar III's sister, Helvig of Schleswig. Helvig was the daughter of Eric II, Duke of Schleswig and Adelaide of Holstein-Rendsburg. The wedding took place at Sønderborg Castle in 1340. As part of the marriage agreement, Helvig brought the pawned province of Nørrejylland, representing one-quarter of Jutland's territory, as her dowry. Following the wedding, the couple traveled to Viborg, where they were officially greeted as the King and Queen of Denmark.

Valdemar IV and Queen Helvig of Schleswig had several children, though not all survived to adulthood:

| Name | Birth | Death | Spouse and Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christopher of Denmark, Duke of Lolland | 1341 | June 11, 1363 | No marriage recorded. |

| Margaret of Denmark | 1345 | 1350 | Betrothed to Henry III, Duke of Mecklenburg; died young. |

| Ingeborg of Denmark, Duchess of Mecklenburg | 1347 | 1370 | Married Henry III, Duke of Mecklenburg in 1362. They had four children: Albert IV, Euphemia, Maria, and Ingeborg (Abbess of the Poor Clares monastery in Ribnitz-Damgarten). Ingeborg was the maternal grandmother of King Eric VII of Denmark. |

| Catherine of Denmark | 1349 | 1349 | Died young. |

| Valdemar of Denmark | 1350 | June 11, 1363 | Died young. |

| Margaret I of Denmark | March 15, 1353 | October 28, 1412 | Married Haakon VI of Norway on April 9, 1363. She became Queen of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, and was the mother of Olaf II. |

There is also some evidence of an illegitimate son named Erik Sjællandsfar, who was reportedly born at Orebygård on Zealand and buried with a crown in Roskilde Cathedral. However, other historical evidence suggests that Erik Sjællandsfar may have been a son of King Eric VI of Denmark instead.

4.2. Cultural references and legends

Valdemar IV has been the subject of numerous stories, ballads, and poems, reflecting his significant place in Danish cultural memory. A famous poem, written by Jens Peter Jacobsen and included in his work Gurresange, tells the tragic tale of Valdemar's mistress, Tove, who was said to have been killed on the orders of Queen Helvig. While this particular legend is strongly associated with Valdemar IV, its origin might actually be connected to his ancestor, Valdemar I of Denmark. The legend gained broader recognition when it was set to music by the renowned composer Arnold Schoenberg from 1900 to 1903 (with additions in 1910) as his monumental cantata, Gurre-Lieder.

Valdemar IV's image underwent a significant transformation in the 19th century. During the mid-19th century Schleswig Wars, when Denmark was engaged in conflicts with Germany over its traditional southern Jutland region, Valdemar was "reinvented" and celebrated as one of Denmark's heroic kings. This reimagining served to bolster national pride and resolve during a period of intense national struggle, cementing his legendary status as a king who brought Denmark "day again" after a dark period.

5. Death

In the final years of his reign, Valdemar IV continued to exert his efforts to consolidate royal power and territorial control. Even while engaged in complex negotiations and conflicts with the Hanseatic League, he was actively working to suppress rebellious nobles across Denmark. These nobles persistently attempted to reassert the rights that Valdemar's father, Christopher II, had been forced to concede. Simultaneously, Valdemar continued to contend with the Swedes and Norwegians, who opposed his expansionist policies. He was in the process of gradually bringing southern Jutland under his firm control when he fell ill.

In an attempt to quell the internal unrest, Valdemar sought the assistance of Pope Gregory XI, who agreed to excommunicate the rebellious Danes. However, before these excommunications could be fully enacted, Valdemar IV died at Gurre Castle in North Zealand on October 24, 1375. His body was interred at Sorø Abbey. Notably, his trusted advisor and prime minister, Henning Podebusk, was later buried next to Valdemar at Sorø Abbey, a testament to their close working relationship.

6. Legacy

Valdemar IV's reign stands as a watershed moment in Danish history, marked by his profound impact on the kingdom's territorial integrity and the re-establishment of royal power, yet also by the enduring criticisms of his methods and the resulting internal strife.

6.1. Achievements and historical significance

King Valdemar IV is widely regarded as a pivotal figure in Danish history, often cited as one of the most important of all medieval Danish kings. His core achievement was the gradual reacquisition of the lost territories that had been fragmented and mortgaged away over the preceding centuries, thereby reunifying Denmark as a cohesive nation. He successfully leveraged his military prowess and the loyalty of a new class of nobility to expand the powers of the king, laying a foundation for Danish rulers that persisted until 1440.

His policies demonstrated a remarkable talent for both politics and economy. Valdemar was adept at strategic financial management, such as selling Danish Estonia to fund the repurchase of more vital Danish lands. He also actively appointed foreign officials and councilors to his court, circumventing traditional noble power structures. The most notable example is Henning Podebusk, a German-Slavic nobleman who served as his drost (prime minister) from 1365 to 1388, playing a critical role in strengthening the centralized administration. Contemporary and historical sources alike portray him as an intelligent, cynical, reckless, and clever ruler, capable of both shrewd political maneuvering and effective economic management. He is celebrated for restoring Denmark's national power, achieving financial reconstruction, and strengthening the military, ultimately leading to a significant advancement of the Danish state.

6.2. Criticisms and controversies

Despite his significant achievements, Valdemar IV's reign was not without substantial criticism and controversy. His methods were often described as heavy-handed and ruthless, particularly his relentless and seemingly endless taxation. These policies, coupled with his systematic usurpation of rights long held by the noble families, triggered widespread uprisings throughout his reign. While his initial ambition to recreate Denmark as a powerful entity in northern Europe was met with some initial support from Danes, his policies ultimately faced bitter opposition from the great landed families, especially those in Jutland. These powerful families resented his centralizing tendencies and the erosion of their traditional privileges, leading to continuous rebellions among both the peasantry and the aristocracy.

6.3. "Atterdag" epithet and public image

Valdemar IV's epithet, "Atterdag," holds significant cultural and historical meaning. It is most commonly interpreted as "day again" or "Return of the Day" in Danish, symbolizing the new hope and brighter era he brought to Denmark after a dark period of weak kingship and national fragmentation.

However, alternative interpretations exist. Some scholars suggest that the epithet might be a misinterpretation of the Middle Low German phrase "ter tage," which translates to "these days" and could be understood as an exclamation like "what times we live in!" Historian Fletcher Pratt, in his biography of Valdemar, proposed it meant "another day," implying a resilient mindset: "whatever happened today, good or bad, tomorrow would be another day."

Beyond scholarly interpretations, Valdemar IV's public image has evolved over time. Many stories, ballads, and poems have been created about him, contributing to his legendary status. He was notably "reinvented" as a Danish hero king during the mid-19th century, especially during the First Schleswig War and Second Schleswig War, when Denmark was fighting Germany over its traditional southern Jutland region. This re-evaluation served a nationalistic purpose, casting him as a symbol of Danish strength and resilience, effectively cementing his legacy as a key figure in the nation's struggle for sovereignty.

7. Descendants

Valdemar IV's failure to leave a surviving male heir directly complicated the succession, making his descendants, particularly his daughters, crucial to the future of the Danish monarchy. His eldest surviving daughter, Ingeborg, married Henry III, Duke of Mecklenburg. Their son, Albert, was unsuccessfully put forward as Valdemar's successor by his grandfather, Albert II, Duke of Mecklenburg.

However, the succession ultimately fell to Valdemar's grandson, Olaf II, the son of his youngest daughter, Margaret I of Denmark, and Haakon VI of Norway. Margaret I (1353-1412) was a remarkably skilled politician and became Queen of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Her strategic marriage to King Haakon VI of Norway was instrumental, as it was through her son, Olaf II, that the succession to the Danish and Norwegian thrones was secured. Following Olaf's premature death, Margaret skillfully navigated the political landscape to ensure her continued influence and eventually laid the groundwork for the Kalmar Union in 1397, uniting the crowns of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under a single monarch. Her actions ensured Valdemar IV's lineage continued to shape Nordic history for centuries.