1. Overview

Sri Aurobindo, born Aurobindo Ghose on August 15, 1872, was a prominent Indian philosopher, yogi, poet, and nationalist who played a significant role in India's struggle for independence from British colonial rule. Initially an influential leader in the nascent revolutionary movement, he later transitioned into a profound spiritual reformer. His vision centered on the concept of Integral Yoga, a spiritual practice aimed at transforming human consciousness and life itself into a divine existence on Earth. He believed in a spiritual realization that not only liberated individuals but also transformed human nature, fostering a divine life for all.

Aurobindo's early life included a Western education in England, where he prepared for the Indian Civil Service before returning to India. There, he became deeply involved in nationalist politics, advocating for India's freedom through both public non-cooperation and secret revolutionary activities. His arrest and subsequent imprisonment in connection with the Alipore Bomb Case marked a turning point, leading to profound spiritual experiences that redirected his focus from politics to spiritual pursuits.

Settling in Pondicherry, a French colony at the time, Sri Aurobindo developed his unique spiritual philosophy of Integral Yoga, which he expounded in prolific writings such as The Life Divine and The Synthesis of Yoga. He collaborated closely with Mirra Alfassa, known as "The Mother," with whom he founded the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, a community dedicated to their spiritual work. Their collective efforts extended to establishing the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education and later, Auroville, an international township envisioned as a place for human unity and spiritual evolution.

His philosophical contributions include the concept of the Supermind, an intermediary power facilitating the evolution of consciousness towards a divine existence. He engaged critically with traditional Indian philosophies like Shankara's Mayavada, advocating for a world-affirming spiritual path, and integrated ancient Indian wisdom with Western philosophical and scientific insights. Sri Aurobindo's extensive literary output, including the epic poem Savitri, reflects his deep spiritual insights and poetic genius. His legacy continues to influence spiritual thought, social reform, and various philosophical disciplines, with a global following dedicated to his teachings on human progress and spiritual transformation.

2. Biography

Sri Aurobindo's life journey was marked by significant transformations, from his early education in England to his fervent political activism in India, culminating in a profound spiritual awakening that led him to dedicate his life to philosophical and yogic pursuits in Pondicherry.

2.1. Early life and education

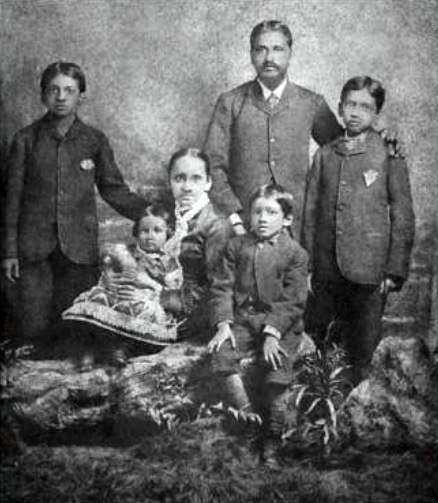

Aurobindo Ghose was born in Calcutta (now Kolkata), Bengal Presidency, India, on August 15, 1872. He hailed from a Bengali Kayastha family associated with Konnagar in the Hooghly district of present-day West Bengal. His father, Krishna Dhun Ghose, was an assistant surgeon in Rangpur District and later a civil surgeon in Khulna. A former member of the Brahmo Samaj religious reform movement, Krishna Dhun Ghose developed an interest in the concept of evolution during his medical studies in Edinburgh. Aurobindo's mother, Swarnalata Devi, was the daughter of Rajnarayan Basu, a prominent figure in the Brahmo Samaj. She had been sent to Calcutta for Aurobindo's birth due to its more salubrious environment. Aurobindo had two elder brothers, Benoybhusan and Manmohan Ghose, a younger sister, Sarojini, and a younger brother, Barindra Kumar Ghose (also known as Barin).

Young Aurobindo was raised speaking English, though he used Hindustani to communicate with servants. His father, believing in the superiority of British culture, sent Aurobindo and his two elder siblings to the English-speaking Loreto House boarding school in Darjeeling. This decision was partly to improve their language skills and partly to distance them from their mother, who had developed a mental illness after the birth of her first child. Darjeeling, a center for Anglo-Indians, and the school, run by Irish nuns, exposed the boys to Christian religious teachings and symbolism.

2.2. England (1879-1893)

Krishna Dhun Ghose desired for his sons to join the Indian Civil Service (ICS), an elite organization. To facilitate this, the entire family moved to England in 1879. Krishna Dhun Ghose soon returned to India, leaving his wife in London under the care of a physician. Barindra was born in England in January 1880. The three brothers were placed under the care of the Reverend W. H. Drewett, a minister of the Congregational church, in Manchester. Drewett and his wife taught the boys Latin, a prerequisite for admission to good English schools.

In 1881, the two elder siblings were enrolled at Manchester Grammar School. Aurobindo, deemed too young, continued his studies with the Drewetts, learning history, Latin, French, geography, and arithmetic. Despite instructions not to teach religion, the boys were exposed to Christian teachings, which Aurobindo generally found boring and sometimes repulsive. Communication with his father was minimal, but his letters indicated a growing disenchantment with the British in India, once describing the colonial government as "heartless."

In 1884, Drewett emigrated to Australia, leading the boys to move to London to live with Drewett's mother. In September of that year, Aurobindo and Manmohan joined St Paul's School. Aurobindo learned Greek and spent his last three years immersed in literature and English poetry, also gaining familiarity with German and Italian. Peter Heehs states that by the turn of the century, Aurobindo knew at least twelve languages: English, French, and Bengali (to speak, read, and write); Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit (to read and write); Gujarati, Marathi, and Hindi (to speak and read); and Italian, German, and Spanish (to read). Exposure to the evangelical environment of Drewett's mother led him to a distaste for religion; he considered himself an atheist at one point, later identifying as agnostic. A blue plaque unveiled in 2007 commemorates his residence at 49 St Stephen's Avenue in Shepherd's Bush, London, from 1884 to 1887. By 1887, the brothers lived in spartan conditions at the Liberal Club in South Kensington due to their father's financial difficulties.

By 1889, Manmohan decided on a literary career, and Benoybhusan proved unsuitable for ICS entry. This left Aurobindo as the sole hope for his father's aspirations, necessitating hard study for a scholarship. He secured a scholarship at King's College, Cambridge, recommended by Oscar Browning. He passed the written ICS examination within months, ranking 11th out of 250 competitors. He spent the next two years at King's College. However, Aurobindo had no interest in the ICS and intentionally arrived late for the horse-riding practical exam to disqualify himself. In 1891, Sri Aurobindo felt a period of great upheaval was approaching for his homeland, in which he was destined to play an important role. He began learning Bengali and joined a secret society called 'Lotus and Dagger,' whose members swore to work for India's freedom.

During this time, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, the Maharaja of Baroda, was traveling in England. Henry John Stedman Cotton secured a place for Aurobindo in the Baroda State Service and arranged a meeting with the prince. Aurobindo left England for India, arriving in February 1893. Tragically, Krishna Dhun Ghose, awaiting his son's arrival, received false information from his agents in Bombay (now Mumbai) that Aurobindo's ship had sunk off the coast of Portugal. His father died upon hearing this news.

2.3. Baroda and Calcutta (1893-1910)

In Baroda, Aurobindo joined the state service in 1893. He initially worked in the Survey and Settlements department, then moved to the Department of Revenue, and later to the Secretariat. His duties also included teaching grammar and assisting in writing speeches for the Maharaja of Gaekwad until 1897. In 1897, he began working as a part-time French teacher at Baroda College (now Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda), where he was later promoted to vice-principal. During his time in Baroda, Aurobindo self-studied Sanskrit and Bengali.

While in Baroda, he contributed numerous articles to Indu Prakash and served as chairman of the Baroda college board. He developed an active interest in the politics of the Indian independence movement against British colonial rule, operating behind the scenes due to his position in the Baroda state administration. He established connections with resistance groups in Bengal and Madhya Pradesh during his travels. Aurobindo also made contact with prominent nationalist leaders such as Lokmanya Tilak and Sister Nivedita.

Aurobindo frequently traveled between Baroda and Bengal, initially to reconnect with his parents' families and other Bengali relatives, including his sister Sarojini and brother Barin. Later, these travels increasingly focused on establishing resistance groups across the Presidency. He formally moved to Calcutta in 1906 following the announcement of the Partition of Bengal. In 1901, during a visit to Calcutta, he married 14-year-old Mrinalini, the daughter of Bhupal Chandra Bose, a senior government official. Aurobindo was 28 at the time. Mrinalini died seventeen years later in December 1918 during the 1918 flu pandemic.

In 1906, Aurobindo was appointed the first principal of the National College in Calcutta, founded to provide national education to Indian youth. He resigned from this position in August 1907 due to his escalating political involvement. The National College continues today as Jadavpur University, Kolkata. Aurobindo was influenced by studies of rebellions and revolutions against England in medieval France and the revolts in America and Italy. In his public activities, he advocated for Non-cooperation and Passive Resistance; privately, he engaged in secret revolutionary activities as preparation for open revolt if passive resistance failed.

In Bengal, with Barin's assistance, he established contacts and inspired revolutionaries such as Bagha Jatin (Jatin Mukherjee) and Surendranath Tagore. He helped found a series of youth clubs, including the Anushilan Samiti of Calcutta in 1902. Aurobindo attended the 1906 Indian National Congress meeting led by Dadabhai Naoroji and participated as a councilor in formulating the fourfold objectives of "Swaraj, Swadesh, Boycott, and national education." In 1907, at the Surat session of Congress, where moderates and extremists clashed significantly, he led the extremist faction alongside Bal Gangadhar Tilak. The Congress subsequently split after this session. In 1907-1908, Aurobindo traveled extensively to Pune, Bombay, and Baroda to solidify support for the nationalist cause, delivering speeches and meeting with various groups.

2.4. Political activism and imprisonment

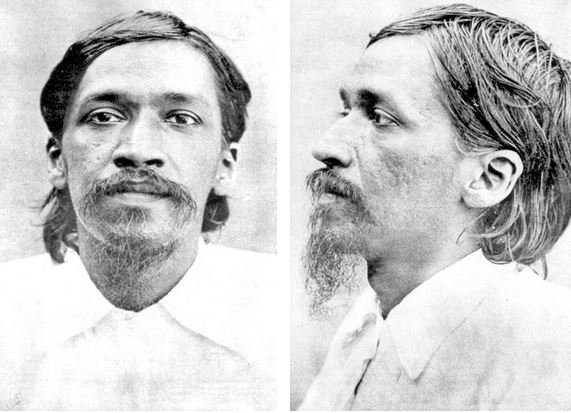

Aurobindo was arrested in May 1908 in connection with the Alipore Bomb Case. This case stemmed from the partition of Bengal in July 1905 by then Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, which ignited widespread public anger and a nationalist campaign by revolutionary groups, including Aurobindo's. In 1908, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki attempted to assassinate Magistrate Kingsford, a judge known for severe sentences against nationalists. However, their bomb missed its target, instead killing two British women, the wife and daughter of barrister Pringle Kennedy. Aurobindo was arrested on charges of planning and overseeing the attack and was imprisoned in solitary confinement in Alipore Jail.

The trial of the Alipore Bomb Case lasted for a year, involving 49 defendants and 206 witnesses, with 400 documents and 5,000 pieces of evidence, including bombs, pistols, and acid. The British judge, C.B. Beachcroft, and Aurobindo were both alumni of Cambridge University. The chief prosecutor, Ardley Norton, displayed a loaded pistol on his briefcase during the trial. Aurobindo's defense counsel was Chittaranjan Das. The trial, later known as the "1908 Alipore Bomb Case," concluded with Aurobindo's acquittal on May 6, 1909. His release followed the murder of the chief prosecution witness, Naren Goswami, within the jail premises, which caused the case against him to collapse. He was released after a year of isolated incarceration.

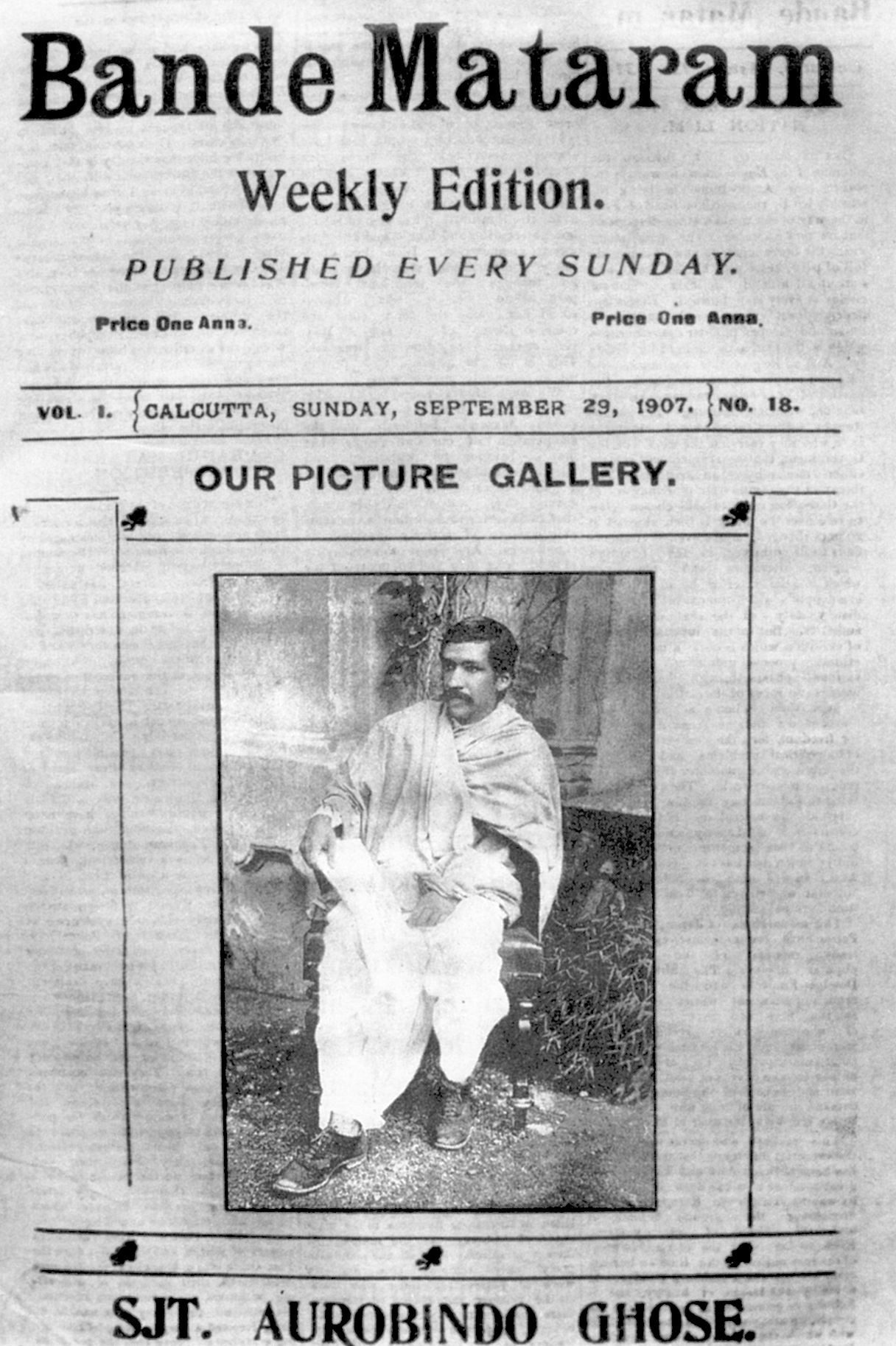

Once out of prison, he launched two new publications: Karmayogin in English and Dharma in Bengali. He also delivered the Uttarpara Speech, hinting at a shift in his focus towards spiritual matters. British colonial government repression continued due to his writings in his new journals. In April 1910, Aurobindo moved to Pondicherry, where the British colonial secret police continued to monitor his activities.

2.5. Conversion from politics to spirituality

During his imprisonment in Alipore Jail, Aurobindo's view of life underwent a radical change due to profound spiritual experiences and realizations. Consequently, his aspirations extended far beyond merely serving and liberating his country. Aurobindo stated that he was "visited" by Swami Vivekananda in Alipore Jail, hearing Vivekananda's voice constantly for a fortnight during his solitary meditation and feeling his presence.

In his autobiographical notes, Aurobindo recounted experiencing a vast sense of calmness upon his initial return to India, which he could not explain. He continued to have various such experiences periodically. At that time, he knew nothing of yoga and began his practice without a teacher, save for some rules he learned from Mr. Devadhar, a friend and disciple of Swami Brahmananda of Ganga Math, Chandod. In 1907, Barin introduced Aurobindo to Vishnu Bhaskar Lele, a Maharashtrian yogi. Aurobindo was significantly influenced by Lele's guidance, which instructed him to rely on an inner guide and that no external guru or guidance would be required.

In 1910, Aurobindo withdrew from all political activities and went into hiding at Chandannagar in the house of Motilal Roy, as the British colonial government sought to prosecute him for sedition based on a signed article titled 'To My Countrymen,' published in Karmayogin. As Aurobindo disappeared from public view, the warrant was held back, and the prosecution postponed. Aurobindo maneuvered the police into open action, and a warrant was issued on April 4, 1910. However, the warrant could not be executed because by that date, he had reached Pondicherry, then a French colony. The warrant against Aurobindo was subsequently withdrawn.

2.6. Pondicherry (1910-1950)

In Pondicherry, Sri Aurobindo dedicated himself entirely to his spiritual and philosophical pursuits. In 1914, after four years of secluded yoga, he launched a monthly philosophical magazine titled Arya. This publication continued until 1921. Many years later, he revised some of these works before their publication in book form. Several significant book series originated from this magazine, including The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, Essays on The Gita, The Secret of The Veda, Hymns to the Mystic Fire, The Upanishads, The Renaissance in India, War and Self-determination, The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, and The Future Poetry.

Initially, during his stay in Pondicherry, he had few followers, but their numbers gradually grew, leading to the establishment of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1926. From 1926 onwards, he began signing his name as Sri Aurobindo, with Sri being a commonly used honorific. For some time thereafter, his primary literary output consisted of his extensive correspondence with his disciples. His letters, most of which were written in the 1930s, numbered in the thousands. Many were brief comments made in the margins of his disciples' notebooks, responding to their questions and reports of their spiritual practice. Others extended to several pages of carefully composed explanations of practical aspects of his teachings. These letters were later compiled and published in three volumes as Letters on Yoga.

In the late 1930s, he resumed work on a poem he had begun earlier, continuing to expand and revise it for the remainder of his life. This monumental work became perhaps his greatest literary achievement, Savitri, an epic spiritual poem in blank verse comprising approximately 24,000 lines. On August 15, 1947, Sri Aurobindo strongly opposed the partition of India, expressing his hope that "the Nation will not accept the settled fact as for ever settled, or as anything more than a temporary expedient."

Sri Aurobindo was nominated twice for the Nobel Prize, though he was not awarded it: in 1943 for the Nobel Prize in Literature and in 1950 for the Nobel Peace Prize. He passed away on December 5, 1950, due to uremia. Approximately 60,000 people attended to see his body resting peacefully. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President Rajendra Prasad praised him for his significant contributions to Yogic philosophy and the independence movement. His death was commemorated by national and international newspapers.

2.7. Mirra Alfassa (The Mother) and the development of the Ashram

Mirra Alfassa, born in Paris on February 21, 1878, to Turkish and Egyptian parents, became Sri Aurobindo's close spiritual collaborator and was widely known as The Mother. In her twenties, she studied occultism with Max Theon. Along with her husband, Paul Richard, she first visited Pondicherry on March 29, 1914, and eventually settled there permanently in 1920. Sri Aurobindo regarded her as his spiritual equal and partner.

After Sri Aurobindo retired into seclusion on November 24, 1926, he entrusted her with the responsibility of planning, building, and managing the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, the community of disciples that had gathered around them. Later, as families with children joined the ashram, she established and supervised the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, conducting innovative experiments in the field of education. This center impressed observers like Jawaharlal Nehru. After Sri Aurobindo's passing in 1950, she continued their spiritual work, directed the ashram, and guided their disciples.

In the mid-1960s, she initiated the establishment of Auroville, an international township near Pondicherry, with the support of UNESCO. Auroville was conceived as an ideal place where men and women from all countries could live in peace and progressive harmony, transcending all nationalities, political ideologies, and creeds. A commemorative ceremony in 1968 saw representatives from 121 nations and all Indian states place a handful of soil into an urn near the center of Auroville. Auroville has since grown to include approximately 1,700 people from 35 countries. The Mother also played an active role in the merger of the French colonies in India and, fulfilling Sri Aurobindo's wish, helped establish Pondicherry as a cultural exchange center between India and France. The Mother continued to reside in Pondicherry until her death on November 17, 1973. Her attempts to establish a new supreme consciousness on Earth and her efforts towards physical transformation are documented in her 13-volume work, Mother's Agenda.

3. Philosophy and Spiritual Vision

Sri Aurobindo's philosophy and spiritual vision center on the concept of Integral Yoga, aiming for a radical transformation of human consciousness and the evolution of life towards a divine existence on Earth.

3.1. Introduction to Integral Yoga

Sri Aurobindo's Integral Yoga system is primarily elaborated in his seminal works, The Synthesis of Yoga and The Life Divine. The Life Divine itself is a compilation of essays originally published serially in his philosophical magazine, Arya.

Sri Aurobindo posited that the divine Brahman manifests as empirical reality through līlā, or divine play. Crucially, he diverged from the traditional Vedantic concept of māyā (illusion), arguing that the world we experience is not merely an illusion but can evolve and give rise to new species, far surpassing the human species, just as humans evolved from animal species. Consequently, he contended that the ultimate goal of spiritual practice should not be limited to liberation from the world into Samadhi, but must also encompass the descent of the Divine into the world to transform it into a Divine existence. This transformative process constitutes the core purpose of Integral Yoga. Regarding the involution of consciousness in matter, he wrote that: "This descent, this sacrifice of the Purusha, the Divine Soul submitting itself to Force and Matter so that it may inform and illuminate them is the seed of redemption of this world of Inconscience and Ignorance."

Sri Aurobindo believed that Darwinism merely describes the phenomenon of the evolution of matter into life but fails to explain the underlying reason. He argued that life is inherently present in matter because all existence is a manifestation of Brahman. He further asserted that nature, which he interpreted as divine, has evolved life out of matter and mind out of life. According to his philosophy, all of existence is striving to manifest the level of the Supermind, indicating that evolution possesses a purpose. He acknowledged that the task of understanding the nature of reality was arduous and difficult to justify by immediate tangible results.

3.2. Integral Yoga: Principles and Practice

Integral Yoga, as conceived by Sri Aurobindo, is a comprehensive spiritual path that integrates the essence of various traditional yogic disciplines, including Karma Yoga, Jnana Yoga, and Bhakti Yoga, to achieve a holistic transformation of human nature and life. Unlike paths that seek liberation from the world, Integral Yoga aims for a descent of divine consciousness into the material realm to divinize earthly existence.

The practice involves a triple transformation:

- Psychic Transformation: This is the awakening of the Psychic Being, the soul or divine spark within, which then takes control of the outer nature (mind, vital, physical). This process brings inner harmony, purity, and devotion.

- Spiritual Transformation: This involves the ascent of consciousness to higher spiritual planes beyond the ordinary mind, leading to experiences of the universal Self, cosmic consciousness, and divine unity. This brings about a profound sense of peace, wideness, and spiritual light.

- Supramental Transformation: This is the ultimate goal, involving the descent of the Supermind into the being, transforming all parts of the nature-mind, vital, and physical-into instruments of the divine. This leads to the manifestation of a "divine life" on Earth, creating a new, "supramental race."

The principles emphasize a continuous and progressive self-perfection, not just individual liberation. It calls for an active engagement with life, transforming all activities into a conscious offering to the Divine. This path embraces the totality of existence, seeing the material world as a field for divine manifestation rather than an illusion to be escaped.

3.3. Supermind and Evolution

At the core of Sri Aurobindo's metaphysical system is the Supermind, which he described as an intermediary power existing between the unmanifested Brahman and the manifested world. Sri Aurobindo asserted that the Supermind is not entirely alien to human experience; it can be realized within ourselves, as it is always present within the mind, containing it as a potentiality. He did not present the Supermind as an original invention but believed its presence could be discerned in the Vedas, where the Vedic Gods represent powers of the Supermind.

In The Integral Yoga, he defined the Supermind as "the full Truth-Consciousness of the Divine Nature in which there can be no place for the principle of division and ignorance; it is always a full light and knowledge superior to all mental substance or mental movement." The Supermind acts as a crucial bridge between Sachchidananda (Existence-Consciousness-Bliss, the ultimate reality of Brahman) and the lower manifestation of the cosmos. It is exclusively through the supramental power that the mind, life, and body can undergo spiritual transformation, a process distinct from direct realization through Sachchidananda. The descent of the Supermind, according to Aurobindo, would lead to the creation of a supramental race, marking the next stage in the evolution of consciousness on Earth.

This evolution, in Aurobindo's view, involves a progression through distinct stages: from matter (as seen in minerals) to life (as in animals) and then to mind (as in humans). These stages represent advancing levels of consciousness development. Consciousness, in this context, is the capacity to grasp truth, and as it ascends through these stages, it progressively draws closer to the ultimate truth of Brahman. The Supermind is the driving force behind this teleological evolution, guiding all existence towards manifesting divine consciousness.

3.4. Metaphysics and Cosmology

According to Sri Aurobindo, the world originates from the process of Brahman's Involution. This concept describes a descent or internalization of the divine consciousness into matter, which then allows the world to manifest. Within this manifested world, the soul becomes internalized, setting the stage for a gradual spiritual evolution.

The Supermind is the fundamental principle that orchestrates this Involution. Sri Aurobindo considered it the fourth principle of Sachchidananda (Existence-Consciousness-Force-Bliss), which he identified as the very nature of Brahman. The Supermind possesses the unique function of limiting the infinite Brahman without actually imposing any limitation upon it. This seemingly contradictory principle operates according to a "logic of the infinite," which transcends finite human reason.

In the process of Involution, the Supermind facilitates the descent of Brahman-or Sachchidananda-into the various levels of our world: matter, life, and the soul. The Supermind itself also descends as spirit. This descent is executed without contradiction, meaning that the Supermind acts as a transcendent mediator between the absolute, unchanging nature of Brahman and the relative, dynamic nature of our manifested world. It is through this mediatory role that the divine potential within creation can gradually unfold and evolve.

3.5. Critique of Traditional Indian Philosophy

Sri Aurobindo critically engaged with aspects of traditional Indian thought, particularly the Mayavada (illusionism) of Advaita Vedanta, as expounded by Adi Shankara. He challenged the notion that the world is merely an illusion (maya), endlessly repeating cycles of destruction and rebirth, and fundamentally distant from the absolute nature of Brahman. Aurobindo argued against this world-negating philosophy, asserting that both the world and humanity within it are capable of attaining absoluteness and divine transformation.

He sought to transcend the conventional Indian philosophical stance that often views the world as an illusory obstacle to be renounced, advocating for renunciation as the sole path to moksha (liberation). Instead, Aurobindo proposed that his Integral Yoga, or Purna Yoga, allows practitioners to embrace and enjoy the world while simultaneously undergoing spiritual enlightenment. He believed that through the integral path, the divine can manifest and transform earthly existence, rather than merely being escaped from. This perspective marked a significant departure from philosophies that emphasized withdrawal from the material world.

3.6. Affinity with Western Philosophy

Sri Aurobindo was well-versed in various European philosophical traditions, referring to several Western philosophers in his writings, talks, and letters. He commented on their ideas and explored potential affinities with his own thought. For instance, he wrote a substantial essay on the Greek philosopher Heraclitus and expressed particular interest in thinkers like Plato, Plotinus, Nietzsche, and Henri Bergson due to their more intuitive approaches to reality. Conversely, he felt little attraction to the philosophies of Kant or Hegel.

Despite his familiarity, Sri Aurobindo generally denied direct influence from Western philosophy on his own writings. However, several scholarly studies have noted a remarkable closeness between his evolutionary thought and that of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whom Aurobindo did not know. Teilhard de Chardin, upon reading chapters of The Life Divine late in his life, reportedly remarked that Sri Aurobindo's vision of evolution was essentially the same as his own, albeit articulated for Asian readers.

Scholars have also identified significant similarities between Sri Aurobindo's thought and that of Hegel. Steve Odin, in a comprehensive comparative study, argued that Sri Aurobindo "has appropriated Hegel's notion of an Absolute Spirit and employed it to radically restructure the architectonic framework of the ancient Hindu Vedanta system in contemporary terms." Odin concluded that both philosophers "similarly envision world creation as the progressive self-manifestation and evolutionary ascent of a universal consciousness in its journey toward Self-realization." However, Odin also highlighted a key difference: while Hegel's dialectic unfolds deterministically, Sri Aurobindo advocated for a "creative, emergent mode of evolution." Odin ultimately suggested that Sri Aurobindo transcended the ahistorical worldview of traditional Hinduism, presenting a concept that allows for genuine progress and novelty.

3.7. Importance of the Upanishads and Vedas

While Sri Aurobindo was deeply familiar with the most significant currents of Western philosophy, he maintained that his own writings were not directly influenced by them. He stated that his philosophy "was formed first by the study of the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita... They were the basis of my first practice of Yoga." He emphasized that his philosophical system was founded on actual spiritual experience, which he pursued with the aid of his readings, rather than on abstract ideas alone.

He believed that the ancient seers of the Upanishads shared a similar experiential approach. In The Renaissance of India, he elaborated on his vision of the past, stating that "The Upanishads have been the acknowledged source of numerous profound philosophies and religions." He even suggested that Buddhism, with all its developments, was merely a "restatement" from a new perspective and with fresh terminology. Furthermore, he noted that the ideas of the Upanishads "can be rediscovered in much of the thought of Pythagoras and Plato and form the profound part of Neo-platonism and Gnosticism..." He concluded that a large portion of German metaphysics "is little more in substance than an intellectual development of great realities more spiritually seen in this ancient teaching." When asked by a disciple if Plato's ideas originated from Indian texts, Aurobindo responded that while some Indian philosophy might have reached Plato through Pythagoras and others, he assumed Plato primarily derived his ideas from intuition.

Sri Aurobindo's profound indebtedness to the Indian tradition is further evident in his practice of prefacing chapters of The Life Divine with numerous quotations from the Rig Veda, the Upanishads, and the Bhagavadgita, thereby explicitly demonstrating the deep connection of his own thought to Veda and Vedanta.

The Isha Upanishad is considered one of Sri Aurobindo's most important and accessible writings. Before publishing his final translation and analysis, he produced ten incomplete commentaries on it. In a pivotal passage, he highlighted that the Brahman, or Absolute, is both the Stable and the Moving, emphasizing that "We must see it in eternal and immutable Spirit and in all the changing manifestations of universe and relativity." His biographer, K.R.S. Iyengar, quoted R.S. Mugali, who suggested that Sri Aurobindo might have found the foundational "thought-seed" for The Life Divine within this particular Upanishad.

3.8. Synthesis and Integration of Thought

Sisir Kumar Maitra, a leading exponent of Sri Aurobindo's philosophy, addressed the question of external influences, noting that while Sri Aurobindo did not explicitly name Western philosophers, "as one reads his books one cannot fail to notice how thorough is his grasp of the great Western philosophers of the present age..." Maitra emphasized that despite being Indian, one should not "underrate the influence of Western thought upon him. This influence is there, very clearly visible, but Sri Aurobindo... has not allowed himself to be dominated by it. He has made full use of Western thought, but he has made use of it for the purpose of building up his own system..." Thus, Maitra, like Steve Odin, viewed Sri Aurobindo not only within the tradition and context of Indian philosophy but also Western philosophy, suggesting he may have adopted elements from the latter for his grand synthesis.

R. Puligandla supported this viewpoint in his book Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy, describing Sri Aurobindo's philosophy as "an original synthesis of the Indian and Western traditions." He stated that Aurobindo "integrates in a unique fashion the great social, political and scientific achievements of the modern West with the ancient and profound spiritual insights of Hinduism. The vision that powers the life divine of Aurobindo is none other than the Upanishadic vision of the unity of all existence."

Puligandla also discussed Sri Aurobindo's critical stance towards Adi Shankara and his thesis that Shankara's Vedanta represents a world-negating philosophy, teaching that the world is unreal and illusory. Puligandla suggested that this might be a misrepresentation of Shankara's position, possibly influenced by Sri Aurobindo's endeavor to synthesize Hindu and Western modes of thought, leading him to identify Shankara's Mayavada with the subjective idealism of George Berkeley.

However, Sri Aurobindo's critique of Shankara is supported by U. C. Dubey in his paper Integralism: The Distinctive Feature of Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy. Dubey highlighted that Sri Aurobindo's system presents an integral view of Reality where there is no opposition between the Absolute and its creative force, as they are fundamentally one. He further referred to Sri Aurobindo's conception of the Supermind as the mediatory principle between the Absolute and the finite world, quoting S.K. Maitra who stated that this conception "is the pivot round which the whole of Sri Aurobindo's philosophy moves." Dubey argued that the Shankarites' approach employs an inadequate form of logic that fails to adequately address the problem of the Absolute, which cannot be comprehended by finite reason. He explained that with finite reason, "we are bound to determine the nature of reality as one or many, being or becoming. But Sri Aurobindo's Integral Advaitism reconciles all apparently different aspects of Existence in an all-embracing unity of the Absolute." Dubey concluded by explaining that for Sri Aurobindo, there exists a higher reason, the "logic of the infinite," which forms the foundation of his integralism.

4. Writings and Literature

Sri Aurobindo's literary output was vast and diverse, encompassing philosophical treatises, poetry, and critical analyses, all contributing to the exposition of his unique spiritual vision.

4.1. Major Works

Sri Aurobindo's most significant books include:

- The Life Divine: This monumental philosophical work, originally serialized in his magazine Arya, delves into the philosophical aspects of Integral Yoga. It articulates his vision of the divine manifestation in the material world and the possibility of human evolution into a divine life on Earth.

- The Synthesis of Yoga: This treatise systematically explores the principles and methods of Integral Yoga, demonstrating how various traditional yogic paths can be integrated into a comprehensive system for spiritual transformation.

- Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol: Considered his magnum opus, this epic spiritual poem, composed in blank verse, spans approximately 24,000 lines. It retells the ancient Indian legend of Savitri and Satyavan as a symbolic narrative of the soul's journey, the conquest of death, and the manifestation of divine consciousness on Earth.

- The Mother: Published in 1928, this concise book serves as a guide for the practice of Integral Yoga. It describes the Divine Mother, the supreme divine consciousness and power, and her four great aspects or primary forces and qualities that guide the universe and interact with earthly play. It also outlines the conditions a yogi must meet to receive the Divine Mother's grace.

- Essays on The Gita: A series of essays offering his profound spiritual interpretation of the Bhagavad Gita, revealing its deeper psychological and yogic insights.

- The Secret of The Veda: In this work, Sri Aurobindo provides an esoteric interpretation of the ancient Vedas, particularly the Rig Veda, uncovering their hidden spiritual and psychological meanings beyond conventional ritualistic or historical interpretations.

- The Upanishads: His translations and commentaries on several principal Upanishads, including the Isha Upanishad, which he considered highly significant for understanding the unity of Spirit and Matter.

- Letters on Yoga: A voluminous collection of thousands of letters written primarily in the 1930s to his disciples. These letters offer practical guidance on various aspects of Integral Yoga, addressing questions and providing explanations of his teachings.

Many of his works, including Hymns to the Mystic Fire, The Renaissance in India, War and Self-determination, The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, and The Future Poetry, were initially published in Arya magazine.

4.2. Publication Editions (Indian)

Sri Aurobindo's collected works have been published in several comprehensive editions in India:

- Sri Aurobindo Birth Centenary Library (SABCL): A first collected edition, published in 1972, comprising 30 volumes. This edition was released by the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, to commemorate his birth centenary.

- Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo (CWSA): A newer, more comprehensive edition that began publication in 1995. As of its ongoing release, 36 out of 37 planned volumes have been published by the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry.

Individual books published in India include:

- Early Cultural Writings

- Collected Poems

- Collected Plays and Stories

- Karmayogin

- Records of Yoga

- Vedic and Philological Studies

- The Secrets of the Veda

- Hymns to the Mystic Fire

- Isha Upanishad

- Kena and Other Upanishads

- Essays on the Gita

- The Renaissance of India with a Defence of Indian Culture

- The Life Divine

- The Synthesis of Yoga

- The Human Cycle - The Ideal of Human Unity - War and Self-Determination

- The Future Poetry

- Letters on Poetry and Art

- Letters on Yoga

- The Mother

- Savitri - A Legend and a Symbol

- Letters on Himself and the Ashram

- Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest

4.3. Publication Editions (American)

Major American editions and publications of Sri Aurobindo's works are primarily released by Lotus Press in Twin Lakes, Wisconsin.

Main works include:

- Sri Aurobindo Primary Works Set 12 vol. US Edition

- Sri Aurobindo Selected Writings Software CD-ROM

- The Life Divine

- Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol

- The Synthesis of Yoga

- Essays on the Gita

- The Ideal of Human Unity

- The Human Cycle: The Psychology of Social Development

- The Human Cycle, Ideal of Human Unity, War and Self Determination

- The Upanishads

- Secret of the Veda

- Hymns to the Mystic Fire

- The Mother

Compilations and secondary literature include:

- The Integral Yoga: Sri Aurobindo's Teaching and Method of Practice

- The Future Evolution of Man

- The Essential Aurobindo - Writings of Sri Aurobindo

- Bhagavad Gita and Its Message

- The Mind of Light

- Rebirth and Karma

- Hour of God

- Dictionary of Sri Aurobindo's Yoga (compiled by M. P. Pandit)

- Vedic Symbolism

- The Powers Within

- Reading Sri Aurobindo

While most of his major works were written in English, they have been extensively translated into various Indian languages, including Hindi, Bengali, Oriya, Gujarati, Marathi, Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam. His works have also been translated into numerous international languages such as French, German, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, Chinese, Portuguese, Slovenian, and Russian, with a substantial volume of his Russian translations available online.

4.4. Comparative Studies

Several scholarly works have analyzed and compared Sri Aurobindo's philosophy and writings with other thinkers and traditions:

- Hemsell, Rod:** His works include The Philosophy of Evolution (Oct. 2014), Sri Aurobindo and the Logic of the Infinite: Essays for the New Millennium (Dec. 2014), and The Philosophy of Consciousness: Hegel and Sri Aurobindo (2017). These studies often explore the unique aspects of Aurobindo's evolutionary thought and its relation to Western philosophical concepts.

- Huchzermeyer, Wilfried:** In Sri Aurobindo's Commentaries on Krishna, Buddha, Christ and Ramakrishna. Their Role in the Evolution of Humanity (Oct. 2018), Huchzermeyer examines Aurobindo's interpretations of major religious figures and their significance for human evolution.

- Johnston, David T.:** His books, Jung's Global Vision: Western Psyche, Eastern Mind, With References to Sri Aurobindo, Integral Yoga, The Mother (Nov. 2016) and Prophets in Our Midst: Jung, Tolkien, Gebser, Sri Aurobindo and the Mother (Dec. 2016), explore the connections between Aurobindo's thought and Western psychological and spiritual traditions.

- Singh, Satya Prakash:** His comparative studies include Nature of God. A Comparative Study in Sri Aurobindo and Whitehead (2013) and Sri Aurobindo, Jung and Vedic Yoga (2005), which delve into the parallels and divergences between Aurobindo's philosophy and other significant intellectual frameworks.

- Weiss, Eric M.:** His 2003 dissertation, The Doctrine of the Subtle Worlds. Sri Aurobindo's Cosmology, Modern Science and the Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, provides an in-depth analysis of Aurobindo's cosmological views in relation to modern science and the metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead.

5. Legacy and Influence

Sri Aurobindo was a notable Indian nationalist, but he is most widely recognized for his profound philosophy on human evolution and Integral Yoga.

5.1. Influence

His influence has been extensive and multifaceted. In India, scholars such as S. K. Maitra, Anilbaran Roy, and D. P. Chattopadhyaya have commented extensively on Sri Aurobindo's work. Within the fields of esotericism and traditional wisdom, figures like Mircea Eliade, Paul Brunton, and René Guénon regarded him as an authentic representative of the Indian spiritual tradition. However, René Guénon also expressed concerns that some of Sri Aurobindo's followers might have distorted his thoughts and that certain works published under his name were not authentic or traditional.

Haridas Chaudhuri and Frederic Spiegelberg were among those deeply inspired by Aurobindo. They contributed to the newly formed American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco. Subsequently, Chaudhuri and his wife, Bina, established the Cultural Integration Fellowship, which later evolved into the California Institute of Integral Studies.

Sri Aurobindo's vision also influenced political leaders. Subhash Chandra Bose was inspired by Aurobindo to dedicate himself full-time to the Indian National Movement, stating, "The illustrious example of Arabindo Ghosh looms large before my vision. I feel that I am ready to make the sacrifice which that example demands of me."

His impact extended to the arts and academia. The German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was profoundly inspired by Satprem's writings about Sri Aurobindo during a personal crisis in May 1968, finding Aurobindo's philosophies highly relevant to his feelings. Following this experience, Stockhausen's music took a completely new direction, focusing on mysticism, a theme that continued throughout the rest of his career. The Swiss philosopher Jean Gebser acknowledged Sri Aurobindo's influence on his work, referring to him multiple times in his writings. In The Invisible Origin, Gebser quoted a long passage from The Synthesis of Yoga and believed he was "in some way brought into the extremely powerful spiritual field of force radiating through Sri Aurobindo." In his book Asia Smiles Differently, Gebser recounted his visit to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram and his meeting with The Mother, whom he described as an "exceptionally gifted person."

The Danish author and artist Johannes Hohlenberg, after meeting Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry in 1915, published one of the first Yoga titles in Europe. He later wrote two essays on Sri Aurobindo and published extracts from The Life Divine in Danish translation. The Chilean Nobel Prize laureate Gabriela Mistral lauded Sri Aurobindo as "a unique synthesis of a scholar, a theologian and one who is enlightened." She further praised his "gift of Civil Leadership, the gift of Spiritual Guidance, the gift of Beautiful Expression: this is the trinity, the three lances of light with which Sri Aurobindo has reached the great number of Indians..."

William Irwin Thompson traveled to Auroville in 1972, where he met The Mother. Thompson characterized Sri Aurobindo's teaching on spirituality as "radical anarchism" and a "post-religious approach," viewing their work as having "...reached back into the Goddess culture of prehistory, and, in Marshall McLuhan's terms, 'culturally retrieved' the archetypes of the shaman and la sage femme..." Thompson also reported experiencing Shakti, or psychic power, emanating from The Mother on the night of her death in 1973.

Sri Aurobindo's ideas concerning the further evolution of human capabilities significantly influenced the thinking of Michael Murphy, and indirectly, the human potential movement, through Murphy's writings. The American philosopher Ken Wilber has referred to Sri Aurobindo as "India's greatest modern philosopher sage" and has incorporated some of his ideas into his own philosophical framework. However, Wilber's interpretation of Aurobindo has faced criticism from scholars like Rod Hemsell. New Age writer Andrew Harvey also regards Sri Aurobindo as a major source of inspiration.

5.2. Followers

Numerous authors, disciples, and organizations trace their intellectual heritage to, or have been significantly influenced by, Sri Aurobindo and The Mother.

- Nolini Kanta Gupta (1889-1983) was one of Sri Aurobindo's senior disciples. He wrote extensively on philosophy, mysticism, and spiritual evolution, basing his works on the teachings of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother.

- Nirodbaran (1903-2006) was a medical doctor who obtained his degree from Edinburgh. His long and voluminous correspondence with Sri Aurobindo elucidates many aspects of Integral Yoga, and his meticulous records of conversations provide insights into Sri Aurobindo's thoughts on numerous subjects.

- M. P. Pandit (1918-1993) served as secretary to The Mother and the ashram. His copious writings and lectures cover a wide range of topics, including Yoga, the Vedas, Tantra, and Sri Aurobindo's epic Savitri.

- Sri Chinmoy (1931-2007) joined the ashram in 1944. He later wrote a play about Sri Aurobindo's life, Sri Aurobindo: Descent of the Blue, and a book titled Infinite: Sri Aurobindo. He was also known for organizing public events focused on inner peace and world harmony, such as concerts, meditations, and races.

- Pavitra (1894-1969), born Philippe Barbier Saint-Hilaire in Paris, was one of their early disciples. His interesting memoirs of conversations with Sri Aurobindo and The Mother in 1925 and 1926 were published as Conversations avec Pavitra.

- Dilipkumar Roy (1897-1980) was an Indian Bengali musician, musicologist, novelist, poet, and essayist, significantly influenced by Aurobindo.

- T.V. Kapali Sastry (1886-1953) was an eminent author and Sanskrit scholar. He joined the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in 1929 and wrote books and articles in four languages, particularly exploring Sri Aurobindo's Vedic interpretations.

- Satprem (1923-2007) was a French author and an important disciple of The Mother. He is known for publishing Mother's Agenda (1982) and authoring works such as Sri Aurobindo or the Adventure of Consciousness (2000) and On the Way to Supermanhood (2002).

- Indra Sen (1903-1994) was another disciple of Sri Aurobindo. Although less known in the West, he was the first to articulate integral psychology and integral philosophy in the 1940s and 1950s. A compilation of his papers was published under the title Integral Psychology in 1986.

- K. D. Sethna (1904-2011) was an Indian poet, scholar, writer, cultural critic, and a disciple of Sri Aurobindo. For several decades, he served as the editor of the Ashram journal Mother India.

- Margaret Woodrow Wilson (1886-1944), known as Nistha, was the daughter of US President Woodrow Wilson. She came to the ashram in 1938 and remained there until her death. She assisted in preparing a revised edition of The Life Divine.

- Xu Fancheng (1909-2000), also known as Hsu Hu, was a Chinese Sanskrit scholar. He arrived at the Ashram in 1951 and became a devotee of Sri Aurobindo and a follower of The Mother. For 27 years (1951-1978), he lived in Pondicherry and dedicated himself to translating the complete works of Sri Aurobindo under The Mother's guidance.

5.3. Critics

Despite his widespread influence, Sri Aurobindo's philosophy and actions have also drawn critical perspectives:

- Adi Da, an American spiritual teacher, argued that Sri Aurobindo's contributions were primarily literary and cultural, and that he had extended his political motivations into the realms of spirituality and human evolution.

- N. R. Malkani, an Indian philosopher, found Sri Aurobindo's theory of creation to be flawed. He contended that the theory describes experiences and visions beyond normal human perception, suggesting it is an intellectual response to a difficult problem. Malkani criticized Sri Aurobindo for using unpredictability in theorizing and discussing matters not based on the truth of existence, asserting that awareness is already a reality and thus, there would be no need to examine creative activity subjected to awareness.

- Ken Wilber's interpretation of Sri Aurobindo's philosophy diverged from Aurobindo's proposed levels of reality (matter, life, mind, overmind, supermind) in The Life Divine. Wilber instead termed these as higher- or lower-nested holons and posited a fourfold reality system of his own creation.

- Rajneesh (Osho), another Indian spiritual teacher, in response to his devotees suggesting that "Sri Aurobindo says there is something more than the enlightenment of Gautam Buddha," famously stated that Sri Aurobindo "knows everything about enlightenment, but he is not enlightened."

6. In Popular Culture

Sri Aurobindo's life and work have been depicted and referenced in various forms of popular culture:

- The 1970 Indian Bengali-language biographical drama film Mahabiplabi Aurobindo, directed by Dipak Gupta, brought Sri Aurobindo's life to the screen.

- On the 72nd Republic Day of India, the Ministry of Culture presented a tableau depicting his life and works, celebrating his 150th birth anniversary.

- A short animation film titled Sri Aurobindo: A New Dawn was released on August 15, 2023, further illustrating his life and teachings.

7. Death

Sri Aurobindo passed away on December 5, 1950, due to uremia. His body lay in state at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, and approximately 60,000 people attended to see him, filing past in absolute silence. Following his death, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President Rajendra Prasad publicly praised him for his profound contributions to Yogic philosophy and his significant role in the Indian independence movement. His passing was widely noted and commemorated by major national and international newspapers, including those in London, Paris, and New York. A writer in the Manchester Guardian called him "the most massive philosophical thinker that modern India has produced."