1. Life

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's life spanned a transformative period in Europe, marked by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, which profoundly shaped his philosophical outlook. His academic career led him through various universities, culminating in his influential professorship at the University of Berlin.

1.1. Formative Years

Hegel was born on 27 August 1770 in Stuttgart, the capital of the Duchy of Württemberg in the Holy Roman Empire, now part of southwestern Germany. He was christened Georg Wilhelm Friedrich but was known as Wilhelm within his close family. His father, Georg Ludwig Hegel (1733-1799), served as a secretary in the revenue office at the court of Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg. His mother, Maria Magdalena Louisa Hegel (née Fromm, 1741-1783), was the daughter of Ludwig Albrecht Fromm, a lawyer at the High Court of Justice in the Württemberg court. Tragically, she died of bilious fever when Hegel was thirteen, a disease he and his father also contracted but narrowly survived.

Hegel had two siblings: a sister, Christiane Luise Hegel (1773-1832), and a brother, Georg Ludwig (1776-1812), who later died as an officer during Napoleon's 1812 Russian campaign. At the age of three, Hegel began attending the German School, and by five, he entered the Latin School, having already learned the first declension from his mother. In 1776, he enrolled in Stuttgart's Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium. During his adolescence, he was an avid reader, meticulously copying lengthy extracts into his diary. His readings included the poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock and prominent Enlightenment writers such as Christian Garve and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. His first biographer, Karl Rosenkranz, noted in 1844 that Hegel's education there "belonged entirely to the Enlightenment with respect to principle, and entirely to classical antiquity with respect to curriculum." He concluded his Gymnasium studies with a graduation speech titled "The abortive state of art and scholarship in Turkey."

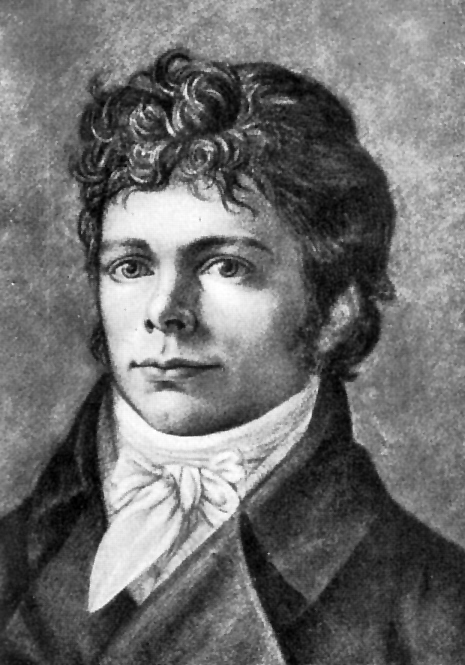

At eighteen, Hegel entered the Tübinger Stift, a Protestant seminary affiliated with the University of Tübingen. There, he shared a room with the poet and philosopher Friedrich Hölderlin and the future philosopher Friedrich Schelling.

The three young men, sharing a mutual dislike for the seminary's restrictive environment, formed a close friendship and profoundly influenced each other's intellectual development. Although Hegel "had a profound distaste for the study of orthodox theology" and never intended to become a minister, his attendance at the state-funded Stift was primarily for financial reasons. All three friends harbored a deep admiration for Hellenic civilization, with Hegel extensively engaging with the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Lessing during this period. They enthusiastically followed the unfolding French Revolution, and despite the violence of the 1793 Reign of Terror dampening his initial hopes, Hegel continued to identify with the moderate Girondin faction. He famously expressed his enduring commitment to the principles of 1789 by toasting the storming of the Bastille every fourteenth of July. While Schelling and Hölderlin delved into theoretical debates on Kantian philosophy, Hegel initially remained detached, only beginning his critical engagement with Kantianism around 1800. At this time, Hegel envisioned himself as a Popularphilosoph (a "man of letters") who would make complex philosophical ideas accessible to a broader public.

After receiving his theological certificate from the Tübingen Seminary, Hegel became a Hofmeister (house tutor) for an aristocratic family in Bern from 1793 to 1796. During this period, he wrote texts such as the Life of Jesus and the book-length manuscript "The Positivity of the Christian Religion." His relationship with his employers grew strained, leading him to accept an offer, mediated by Hölderlin, to take a similar position with a wine merchant's family in Frankfurt in 1797. In Bern, Hegel's writings had been sharply critical of orthodox Christianity, but in Frankfurt, under the influence of early Romanticism, he explored the mystical experience of love as the true essence of religion. Also in 1797, the unpublished and unsigned manuscript of "The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism" was written in Hegel's hand, though its authorship is disputed between Hegel, Schelling, and Hölderlin. While in Frankfurt, he also composed the essay "Fragments on Religion and Love" and in 1799, "The Spirit of Christianity and Its Fate," which remained unpublished during his lifetime.

1.2. Academic Career

In 1801, Hegel moved to Jena at the urging of Schelling, who was an Extraordinary Professor at the University of Jena. Hegel secured a position as a Privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer) after submitting his inaugural dissertation, De Orbitis Planetarum, where he briefly criticized mathematical arguments asserting the existence of a planet between Mars and Jupiter. Later that year, he completed his essay The Difference Between Fichte's and Schelling's System of Philosophy. He lectured on "Logic and Metaphysics" and, with Schelling, on an "Introduction to the Idea and Limits of True Philosophy," also facilitating a "philosophical disputorium." In 1802, Schelling and Hegel co-founded the Kritische Journal der Philosophie (Critical Journal of Philosophy), to which they contributed until Schelling's departure for Würzburg in 1803.

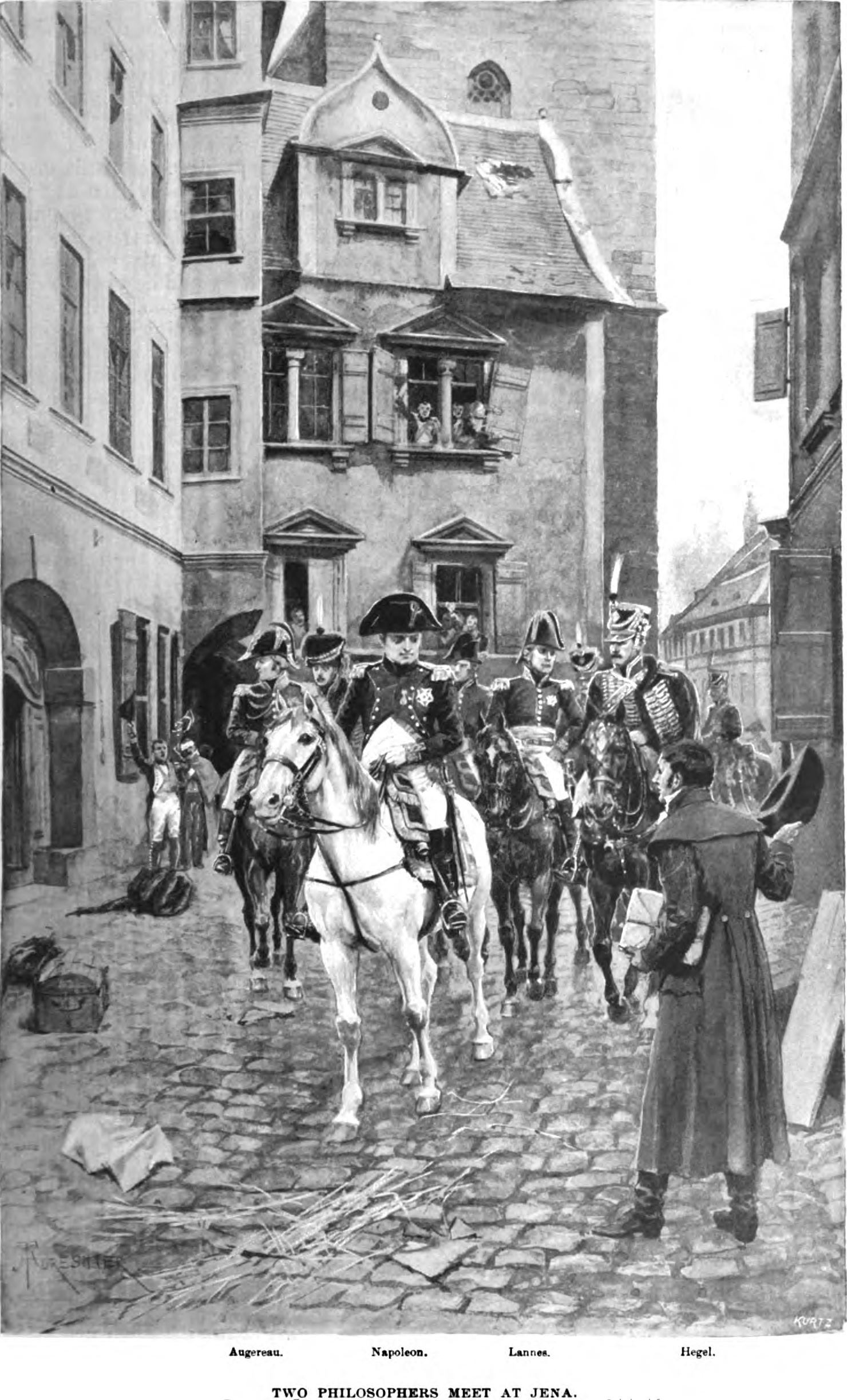

In 1805, the university promoted Hegel to the unsalaried position of extraordinary professor after he wrote to the poet and Minister of Culture Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, protesting the promotion of his philosophical adversary Jakob Friedrich Fries ahead of him. His attempt to secure a post at the renascent University of Heidelberg through the help of the poet and translator Johann Heinrich Voß failed, and Fries was, to his chagrin, appointed ordinary (salaried) professor in the same year. In February 1807, Hegel's illegitimate son, Georg Ludwig Friedrich Fischer (1807-1831), was born from an affair with his landlady, Christiana Burkhardt née Fischer. Facing severe financial strain, Hegel was under immense pressure to complete his long-promised introduction to his philosophical system, The Phenomenology of Spirit. He was putting the finishing touches on it as Napoleon's troops engaged the Prussians on 14 October 1806, in the Battle of Jena on a plateau outside the city.

On the day before the battle, Napoleon entered Jena. Hegel famously recounted his impressions in a letter to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

I saw the Emperor - this world-soul [Weltseele] - riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it.

Hegel biographer Terry Pinkard notes that Hegel's comment was "all the more striking since he had already composed the crucial section of the Phenomenology in which he remarked that the Revolution had now officially passed to another land (Germany) that would complete 'in thought' what the Revolution had only partially accomplished in practice." Although Napoleon largely spared the University of Jena from the destruction of the surrounding city, few students returned after the battle, and enrollment suffered, worsening Hegel's financial prospects. He traveled to Bamberg that winter to oversee the proofs of the Phenomenology, which was being printed there. Unable to secure another professorship, Hegel moved to Bamberg in 1807, as his savings and the payment from the Phenomenology were exhausted, and he needed to support his illegitimate son Ludwig. There, with Niethammer's help, he became the editor of the local pro-French newspaper, Bamberger ZeitungGerman. Ludwig Fischer and his mother remained in Jena.

As editor of the Bamberger ZeitungGerman, Hegel praised Napoleon and often editorialized against Prussian war accounts. He became a notable figure in Bamberg's social life, visiting local official Johann Heinrich Liebeskind and indulging in cards, fine dining, and local Bamberg beer. However, he scorned "old Bavaria," often calling it "Barbaria," fearing that local towns like Bamberg would lose autonomy under the new Bavarian state. After being investigated in September 1808 for publishing French troop movements, Hegel wrote to Niethammer, by then a high official in Munich, seeking a teaching post. With Niethammer's help, Hegel was appointed headmaster of a gymnasium in Nuremberg in November 1808, a position he held until 1816. In Nuremberg, he adapted his Phenomenology of Spirit for classroom use, teaching an "Introduction to Knowledge of the Universal Coherence of the Sciences." In 1811, Hegel married Marie Helena Susanna von Tucher (1791-1855), the eldest daughter of a Senator. This period saw the publication of his second major work, the Science of Logic (Wissenschaft der Logik; 3 vols., 1812, 1813, and 1816), and the birth of two sons, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm (1813-1901) and Immanuel Thomas Christian (1814-1891).

After receiving offers from the Universities of Erlangen, Berlin, and Heidelberg, Hegel chose Heidelberg, moving there in 1816. His illegitimate son Ludwig Fischer (then ten years old), who had been in an orphanage after his mother's death, joined the Hegel household in April 1817. In 1817, Hegel published The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline as a summary for his students. It was also in Heidelberg that he first lectured on the philosophy of art. In 1818, Hegel accepted the renewed offer of the chair of philosophy at the University of Berlin, vacant since Johann Gottlieb Fichte's death in 1814. Here, he published his Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1821). Hegel primarily focused on lecturing; his lectures on the philosophy of fine art, the philosophy of religion, the philosophy of history, and the history of philosophy were published posthumously from student notes. Despite his notoriously poor delivery, his fame grew, attracting students from across Germany and beyond. During this time, Hegel and his pupils, including Leopold von Henning and Friedrich Wilhelm Carové, faced harassment and surveillance from Prince Sayn-Wittgenstein, the Prussian interior minister, and his reactionary court circles. In his remaining career, he traveled twice to Weimar, meeting Goethe for the last time, and visited Brussels, the Northern Netherlands, Leipzig, Vienna, Prague, and Paris.

1.3. Later Life and Death

During the last decade of his life, Hegel did not publish another book but thoroughly revised the Encyclopedia (second edition, 1827; third, 1830). In his political philosophy, he criticized Karl Ludwig von Haller's reactionary work, which argued that laws were unnecessary. A number of other works on the philosophy of history, religion, aesthetics, and the history of philosophy were compiled from his students' lecture notes and published posthumously.

Hegel was appointed University Rector in October 1829, serving until September 1830. He was deeply disturbed by the riots for reform in Berlin that year. In 1831, Frederick William III decorated him with the Order of the Red Eagle, 3rd Class, for his service to the Prussian state. In August 1831, a cholera epidemic reached Berlin, prompting Hegel to leave for Kreuzberg. Already in poor health, he seldom went out. Believing the epidemic had largely subsided, Hegel returned to Berlin for the new semester in October. By November 14, Hegel was dead. Physicians declared cholera as the cause, though it is possible he succumbed to another gastrointestinal illness. His last words are said to have been, "There was only one man who ever understood me, and even he didn't understand me." He was buried on November 16, as per his wishes, in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery next to Fichte and Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand Solger.

Hegel's illegitimate son, Ludwig Fischer, had died shortly before while serving with the Dutch army in Batavia, but the news never reached his father. Early the following year, Hegel's sister Christiane committed suicide by drowning. His two remaining sons - Karl, who became a historian, and Immanuel Thomas Christian, who followed a theological path - lived long lives and safeguarded their father's manuscripts and letters, producing editions of his works.

2. Influences

Hegel's philosophical development was shaped by a rich tapestry of intellectual currents and specific thinkers, from classical antiquity to his Enlightenment contemporaries.

2.1. Ancient Philosophy

When Hegel entered the Tübingen seminary in 1788, he was a typical product of the German Enlightenment, an enthusiastic reader of Rousseau and Lessing, and acquainted with Kant. However, he was perhaps more deeply devoted to the classics than to modern thought, with the Greeks, especially Plato, being his primary focus during this early period. Although he later elevated Aristotle above Plato, Hegel never abandoned his love for ancient philosophy, and its influence is pervasive throughout his work. His concept of spirit (Geist), particularly evident in his anthropology, is an appropriation and transformation of Aristotle's self-referential concept of energeia. Similarly, in discussing the mind-body problem, Hegel utilizes and develops Aristotle's hylomorphic approach, asserting that the mind does not act on the body as a cause of effects, but rather acts on itself as an embodied living subjectivity, progressively developing a self-determined character.

2.2. Enlightenment and German Idealism

Hegel's early concern with various forms of cultural unity (Judaic, Greek, medieval, and modern) persisted throughout his career, reflecting his typical engagement with early German Romanticism. The phrase "unity of life" was central to Hegel and his generation, expressing their concept of the highest good-unity with oneself, with others, and with nature, with division (Entzweiung) or alienation (Entfremdung) being the main threats. In this context, Hegel was particularly drawn to the phenomenon of love as a "unity-in-difference," both in Plato's ancient articulation and in Christianity's doctrine of agape, which he saw as "already 'grounded on universal Reason." This interest, alongside his theological training, continued to shape his thought as it moved towards a more theoretical and metaphysical direction.

It was Kant's critical philosophy that provided what Hegel considered the definitive modern articulation of the philosophical divisions that needed to be overcome. This engagement led to his interaction with the philosophical programs of Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Schelling, as well as his attention to Spinoza and the Pantheism controversy. The concept of Spirit in Hegel's system shares connections with similar ideas in Fichte's theory of the Ego and Schelling's Absolute.

2.3. Other Key Influences

According to Glenn Alexander Magee, Hegel's thought, particularly the tripartite structure of his system, owes much to the hermetic tradition, especially the work of Jakob Böhme. The conviction that philosophy must take the form of a comprehensive system was particularly inspired by his Tübingen roommates, Schelling and Hölderlin. Hegel also read widely and was significantly influenced by Adam Smith and other theorists of political economy. However, the influence of Johann Gottfried von Herder would lead Hegel to a qualified rejection of the universality claimed by the Kantian program, favoring a more culturally, linguistically, and historically informed account of reason. Herder's emphasis on historical and cultural development contributed to Hegel's historicist approach, where reason itself is seen as having a history, its definition evolving through development rather than being fixed a priori.

3. Philosophical System

Hegel's philosophical system is a comprehensive and integrated framework designed to understand the totality of reality through the development of spirit (Geist). His system is fundamentally characterized by its systematic structure, its dialectical methodology, and its idealistic premise, asserting that the "rational is actual, and the actual is rational." This overarching system is presented in three main parts: the science of logic, the philosophy of nature, and the philosophy of spirit.

This structure, evident in drafts as early as 1805 and fully presented in the 1817 Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, is adopted from Proclus's Neoplatonic triad of 'remaining-procession-return' and from the Christian Trinity. While distinct from Neoplatonism by asserting the immanence of the originary One (to Hen) within the onto-noētic universe, Hegel's system, particularly the logical idea, is non-temporal and manifests through its physical and spiritual expressions. The logical idea aims to articulate "the identity of identity and non-identity" of nature and spirit, thereby overcoming subject-object dualism.

Philosophical historian Frederick C. Beiser argues that the relationship between logic and the real philosophy in Hegel's system is best understood through Aristotle's distinction between "the order of explanation" and "the order of being." Hegel is a holist, asserting that the universal is always primary in explanation, even if the particular is primary in being. He rejects the notion that any one of his system's three parts can be prioritized without leading to a "one-sided" or inaccurate interpretation, famously declaring, "The true is the whole." This means that philosophy, as "its own time comprehended in thoughts," unveils the logical form inherent in natural-historical phenomena.

Hegel famously articulated this concept in his Elements of the Philosophy of Right:

A further word on the subject of issuing instructions on how the world ought to be: philosophy, at any rate, always comes too late to perform this function. As the thought of the world, it appears only at a time when actuality has gone through its formative process and attained its completed state [sich fertig gemacht]. This lesson of the concept is necessarily also apparent from history, namely that it is only when actuality [Wirklichkeit] has reached maturity that the ideal appears opposite the real and reconstructs this real world, which it has grasped in its substance, in the shape of an intellectual realm. When philosophy paints its gray in gray, a shape of life has grown old, and it cannot be rejuvenated, but only recognized, by the gray in gray of philosophy; the owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the onset of dusk.

This passage, often interpreted as philosophy's impotence or a rationalization of the status quo, is nuanced by scholar Allegra de Laurentiis, who points out that the German expression "sich fertig machen" implies not only completion but also preparedness, aligning with Hegel's Aristotelian concept of actuality as "being-at-work-staying-itself" which is never definitively finished. Thus, philosophy reveals the systematically coherent logical form inherent in the dynamic, evolving material of reality.

3.1. The Phenomenology of Spirit

The Phenomenology of Spirit, published in 1807, marks the first full articulation of Hegel's distinctive philosophical approach. Despite its seminal importance, it was poorly understood by his contemporaries and remains notorious for its conceptual density, idiosyncratic terminology, and abrupt transitions. The scholar Henry Silton Harris's two-volume commentary, Hegel's Ladder, is three times the length of the original text, underscoring its complexity.

The fourth chapter of the Phenomenology introduces Hegel's influential lord-bondsman dialectic (Herrschaft und Knechtschaft), often mistakenly translated as "master-slave." This section highlights a conflict where two self-consciousnesses struggle for recognition, revealing that genuine recognition can only be reciprocal. This critique extends to the individualist worldview, asserting that human self-consciousness requires the recognition of others, and one's self-perception is shaped by external views.

Hegel described The Phenomenology as both an "introduction" to his philosophical system and its "first part," calling it the "science of the experience of consciousness." Its systematic role, however, has been consistently debated by scholars, and Hegel's own views on its place evolved. The book aims to demonstrate that even the most basic "certainties of natural consciousness" lead to the standpoint of speculative logic. This is not a Bildungsroman; rather, "we," the phenomenological observers, learn from consciousness's "path of despair" as it repeatedly finds itself in error. The self-concept of consciousness is rigorously tested in experience, and where inadequate, it "suffers this violence at its own hands, and brings to ruin its own restricted satisfaction." As Hegel noted, one cannot learn to swim without entering the water. This process is a "transcendental deduction of metaphysics," where experience, broadly construed beyond mere sense perception, validates metaphysical claims.

The Phenomenology argues that because consciousness always includes self-consciousness, there are no 'given' objects of direct awareness that are not already mediated by thought. Reciprocal recognition is essential for the social and conceptual stability of the experiential world. Failures of recognition necessitate reflection on the past to understand present requirements, ultimately leading to an interpretation of "religion as the collective reflection of the modern community on what ultimately counts for it." This historical, socially constructed philosophical account elucidates the genesis of a distinct "modern" standpoint. Influenced by Herder, Hegel's approach is historical rather than purely a priori, yet it resists relativistic consequences by asserting that reason itself has a history and evolves. The book demonstrates that seeking an externally objective criterion for truth is futile; knowledge constraints are internal to spirit. Claims to knowledge must be proven adequate through real historical experience. Despite appearing to abandon it during his Berlin years, Hegel planned to revise and republish The Phenomenology of Spirit before his death, suggesting he still valued it as a unique "science of experience."

3.2. The Science of Logic

Hegel's concept of logic differs significantly from the ordinary English usage, as it functions as "the science of things grasped in [the] thoughts that used to be taken to express the essentialities of the things." It continues Kant's logical program but diverges from Aristotelian and 20th-century formal logics, aspiring instead to be a metaphysical logic of truth. There are two main texts of Hegel's Logic: the comprehensive The Science of Logic (1812, 1813, 1816; Book I revised 1831), known as the "Greater Logic," and the abridged "Lesser Logic" found in the first volume of his Encyclopedia, intended for students.

Hegel presents logic as a presuppositionless science that investigates fundamental thought-determinations, or Kantian categories, forming the very basis of philosophy. He famously states that "logic coincides with metaphysics." For Hegel, this logic provides "an account of pure categories or ideas which are timelessly true" and constitute "the formal structure of reality itself." However, this is not a return to Leibnizian-Wolffian rationalism, which Kant criticized. Hegel rejects any metaphysics as speculation about the transcendent, adopting an immanent procedure, akin to Aristotle's concept of substantial form. He agrees with Kant's critique of dogmatism and insists that any future metaphysics must withstand criticism.

Philosopher Béatrice Longuenesse interprets this project as an "inseparably a metaphysical and a transcendental deduction of the categories of metaphysics." This means logic's insights cannot be judged by external standards, and thought is not merely a mirror of nature; yet, these standards are neither arbitrary nor subjective. George di Giovanni also views the Logic as immanently transcendental, with its categories built into "life itself" and defining "an object in general."

The Logic is divided into three books: the doctrines of "Being" and "Essence," which together form the Objective Logic, focusing on overcoming traditional metaphysical assumptions, and the doctrine of "the Concept," which reintegrates categories of objectivity into an idealistic account of reality. Simply put, Being describes concepts as they appear; Essence explains them through opposites; and the Concept unites both via an internal teleology. Categories of Being "pass over" into one another, Essence categories "shine" into each other, and Concept categories organically "develop" from one to the next, demonstrating thought's self-referential nature.

Hegel's "concept" (Begriff), when used with the definitive article, refers to the intelligible structure of reality articulated in the Subjective Logic, not a psychological notion. His inquiry into thought systematizes its internal self-differentiation, showing how pure concepts differ in implication and interdependence. For instance, the opening dialectic of the Logic demonstrates that "being, pure being - without further determination" is indistinguishable from nothing, their "passing back and forth" forming the category of becoming. This movement is a dialectic one can only observe and describe.

The final category of the Logic is "the idea," also not a psychological concept for Hegel. Following Kant's The Critique of Pure Reason, Hegel's use harkens back to the Greek eidos, Plato's concept of form that is fully existent and universal. For Hegel, Idee attempts to fuse ontology, epistemology, and evaluation into a single set of concepts. The Logic accommodates the necessity of natural-spiritual contingency, realizing itself in nature and spirit, where it achieves its "verification." This leads to the conclusion of The Science of Logic with "the idea freely discharging [entläßt] itself" into "objectivity and external life," marking the systematic transition to the Realphilosophie.

3.3. Philosophy of Nature

The philosophy of nature systematically organizes the contingent material of the natural sciences. As part of the philosophy of the real, it does not "tell nature what it must be like." While historical criticisms have questioned Hegel's understanding of contemporary natural sciences, recent scholarship has largely refuted these claims. One of the few ways the philosophy of nature might correct natural sciences is by combating reductive explanations-for example, discrediting attempts to explain life solely in chemical terms, which are inadequate to the phenomena's complexity.

Hegel and other Naturphilosophen sought to revive a teleological understanding of nature, arguing that their strictly internal or immanent concept of teleology "is limited to the ends observable within nature itself," thus not violating the Kantian critique. They contended that Kant's restriction of teleology to a regulative status undermined his own critical project; only by acknowledging the constitutive status of organisms can one explain the "actual interaction" between subjective and objective, ideal and real.

Philosopher Dieter Wandschneider observes that contemporary philosophy of science has overlooked "the ontological issue at stake, namely, the question of an intrinsically lawful nature," advocating for a return to Hegel's philosophy of nature for guidance. Recent scholars also argue that Hegel's approach offers valuable resources for theorizing about modern environmental challenges due to its distinctive metaphysical grounding and its conception of the nature-spirit relationship.

3.4. Philosophy of Spirit

The German word Geist in Hegel's philosophy has a broad spectrum of meanings. In its most general Hegelian sense, Geist "denotes the human mind and its products, in contrast to nature and also the logical idea," encompassing both individual mind and the collective "spirit" shared by a group of people, famously expressed as "I that is We, and We that is I." It also carries the religious connotation of the Holy Spirit, which is always present in Hegel's usage. Hegel's concept of spirit is an appropriation and transformation of the self-referential Aristotelian concept of energeia, understood not as something external to nature but as "the highest organization and development" of nature's inherent powers.

According to Hegel, "the essence of spirit is freedom." The Encyclopedia Philosophy of Spirit systematically charts the progressively determinate stages of this freedom until spirit fulfills the Delphic imperative: "Know thyself." Hegel's concept of freedom transcends mere arbitrary choice; its "core notion" is that "something, especially a person, is free if and only if, it is independent and self-determining, not determined by or dependent upon something other than itself." This is primarily an account of what Isaiah Berlin would later term positive liberty, yet Hegel was also a staunch defender of negative liberty.

3.4.1. Subjective Spirit

The Philosophy of Subjective Spirit serves as the transition from nature to spirit, analyzing the foundational structures of the individual rational agent necessary for objective spirit's relations. It delineates "the fundamental nature of the biological/spiritual human individual along with the cognitive and the practical prerequisites of human social interaction."

It is important to note that this section, particularly its initial part on Anthropology, contains comments prevalent in Hegel's time that are now recognized as explicitly racist. These include unfounded claims about the "naturally" lower intellectual and emotional development of Black people, which Hegel attributed to climatic conditions rather than inherent racial characteristics. However, he believed that "race is not destiny," asserting that any group could improve its condition by migrating to more favorable climates.

Hegel divides his philosophy of subjective spirit into three parts: anthropology, phenomenology, and psychology. Anthropology deals with the "soul," conceived as spirit still immersed in nature, encompassing aspects that precede self-conscious mind or intellect. Phenomenology examines the relationship between consciousness and its object and the emergence of intersubjective rationality. Psychology covers what is now categorized as epistemology, discussing attention, memory, imagination, and judgment. Throughout this section, especially in Anthropology, Hegel utilizes and expands upon Aristotle's hylomorphism to address the mind-body problem, proposing that the mind develops itself as an embodied living subjectivity, progressively achieving a more self-determined character. The final section, "Free Spirit," develops the concept of "free will," which is foundational for Hegel's philosophy of right.

3.4.2. Objective Spirit

Hegel's philosophy of objective spirit is his social philosophy, exploring how human spirit objectifies itself through social and historical activities and productions, essentially an account of the institutionalization of freedom. Scholarship widely agrees that freedom is the most crucial concept in Hegel's political theory, serving as the foundation of right, the essence of spirit, and the telos of history.

This part of Hegel's philosophy first appeared in his 1817 Encyclopedia (revised 1827 and 1830) and was elaborated in his 1821 Elements of the Philosophy of Right, or Natural Law and Political Science in Outline, which he also lectured on extensively. Its final part, the philosophy of world history, was further developed in his lectures on the subject.

Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right has been controversial since its publication. It is not, as some have alleged, a straightforward defense of the autocratic Prussian state, but rather a defense of "Prussia as it was to have become under [proposed] reform administrations." The German term Recht in Hegel's title has no direct English equivalent, encompassing senses of 'a right, claim or title', 'justice', and 'the law'. Beiser argues that Hegel's theory aims to rehabilitate the natural law tradition while incorporating criticisms from the historical school, forming the very foundation of his social and political thought. Scholars like Adriaan T. Peperzak document Hegel's arguments against social contract theory and emphasize the metaphysical foundations of his philosophy of right.

Philosopher Kenneth R. Westphal outlines the structure of Hegel's argument in the Philosophy of Right:

- 'Abstract Right,' addresses principles governing property, its transfer, and wrongs against property.

- 'Morality,' examines the rights of moral subjects, responsibility for actions, and a priori theories of right.

- 'Ethical Life' (Sittlichkeit), analyzes the principles and institutions governing central aspects of rational social life, including the family, civil society, and the state as a whole, including the government.

Hegel describes the state of his time, a constitutional monarchy, as rationally embodying three cooperative and mutually inclusive elements: democracy (rule of the many involved in legislation), aristocracy (rule of the few who apply and execute laws), and monarchy (rule of the one who heads all power). This "mixed" form of government, akin to Aristotle's, is designed to synthesize the best of the classical forms, with a separation of powers preventing single-power domination. Hegel was particularly concerned with binding the monarch to the constitution, limiting authority to merely formal declaration of ministerial decisions.

The relationship of Hegel's philosophy of right to modern liberalism is complex. He viewed liberalism as a valuable expression of the modern world but prone to self-destruction if not balanced by a "larger objective and collective good," thus limiting the scope of moral values. Although he is a major proponent of positive liberty, he was equally "unwavering and unequivocal" in his defense of negative liberty. While his ideal sovereign was weaker than typical monarchs of his era, his democratic element was also less expansive than in modern democracies. He insisted on public participation but severely limited suffrage, following the English bicameral model where only members of the lower house (commoners and bourgeoisie) were elected, with nobles inheriting their positions.

The final part of the Philosophy of Objective Spirit is "World History." Here, Hegel argues that the immanent principle of the Stoic logos "produces with logical inevitability an expansion of the species' capacities for self determination ('freedom') and a deepening of its self understanding ('self-knowing')." In his own words, "World history is progress in the consciousness of freedom - a progress that we must comprehend conceptually."

3.4.3. Absolute Spirit

Hegel's use of the term "absolute" (from Latin absolutus) signifies something "not dependent on, conditional on, relative to or restricted by anything else; self-contained, perfect, complete." For Hegel, absolute knowing denotes "an 'absolute relation' in which the ground of experience and the experiencing agent are one and the same: the object known is explicitly the subject who knows." This means that only that which is entirely self-conditioned is truly absolute, occurring when spirit takes itself as its own object. The final section of his Philosophy of Spirit presents the three modes of such absolute knowing: art, religion, and philosophy.

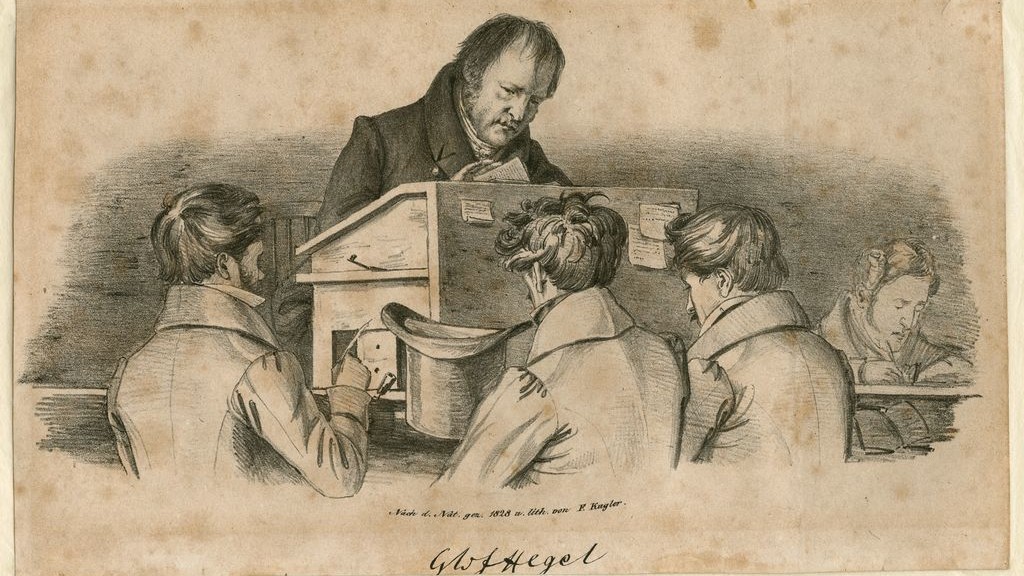

(1828 sketch by F. T. Kugler)

Hegel distinguishes these three modes of absolute knowing by reference to different modalities of consciousness: intuition, representation, and comprehending thinking. Frederick Beiser summarizes: "art, religion and philosophy all have the same object, the absolute or truth itself; but they consist in different forms of knowledge of it. Art presents the absolute in the form of immediate intuition (Anschauung); religion presents it in the form of representation (Vorstellung); and philosophy presents it in the form of concepts (Begriffe)." Philosopher Rüdiger Bubner clarifies that the systematic ordering of these spheres by increasing conceptual transparency is not hierarchical in an evaluative sense. While Hegel's discussion of absolute spirit in the Encyclopedia is brief, he extensively develops this account in his lectures on the philosophy of fine art, the philosophy of religion, and the history of philosophy.

3.5. Philosophy of Art

Hegel's philosophy of art, primarily articulated in his lectures on the philosophy of fine art, develops from an initial treatment in The Phenomenology of Spirit as "Art-Religion" of the ancient Greeks, into an explicitly autonomous domain from 1818 onwards. Hegel explicitly stated that his subject was not merely "the spacious realm of the beautiful" but "art, or, rather, fine art," distinguishing his project from broader "aesthetics" as pursued by Christian Wolff and Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten.

Contrary to the canonical attribution by critics like Benedetto Croce, Hegel never claimed that art is "dead." Instead, his assertion that "art no longer serves our highest aims" was considered radical precisely for suggesting that it ever did. Hegel's detailed and systematic treatment of various art forms has led art historian Ernst Gombrich to recognize him as "the father of art history." For much of their history, Hegel's Lectures were largely overlooked by philosophers but garnered significant attention from literary critics and art historians. The specific conceptual aim of his philosophy of art is to articulate and defend "the autonomy of art, making possible an account of the special individuality distinguishing works of aesthetic worth."

According to Hegel, "artistic beauty reveals absolute truth through perception," meaning the best art conveys metaphysical knowledge by sensually disclosing what is unconditionally true or "absolute" within his metaphysical theory. While art is ennobled for its capacity to convey metaphysical knowledge, Hegel tempers this assessment by acknowledging that art's sensory media can never fully convey what transcends the contingency of sensation. This limitation is why, for Hegel, art is but one of three mutually complementary modes of absolute spirit, alongside religion and philosophy.

3.6. Philosophy of Religion

Although his understanding of Christianity evolved over time, Hegel consistently identified as a Lutheran throughout his life. A constant in his thought was his profound appreciation for the Christian insight into the intrinsic worth and freedom of every individual.

Hegel's earliest writings on Christianity, from 1783 to 1800, were fragmentary and unfinished drafts. During this period, he expressed dissatisfaction with the dogmatism and "positivity" (referring to non-essential, historically derived, and often authoritarian aspects) of Christianity, contrasting it with the spontaneous religion of the Greeks. In The Spirit of Christianity, he proposed a resolution by aligning the universality of Kantian moral philosophy with the universality of Jesus' teachings, paraphrasing that "The moral principle of the Gospel is charity, or love, and love is the beauty of the heart, a spiritual beauty which combines the Greek Soul and Kant's Moral Reason." Although he did not return to this Romantic formulation, the unification of Greek and Christian thought remained a lifelong preoccupation.

Religion is a major theme throughout the 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit, particularly in its depiction of the metaphysical "unhappiness" of the Augustinian consciousness and the struggle between the Church of the Faithful and Enlightenment philosophes. Hegel's main account of Christianity appears in the penultimate "The Revelatory Religion" chapter. Through a philosophical exposition of Christian doctrines like Incarnation and Resurrection, Hegel aimed to demonstrate the conceptual truth of Christianity, making explicit what had only been obscurely "revealed." The core of his interpretation lies in the Trinity: God the Father gives Himself existence as the finite human Son, whose death discloses His essential being as Spirit. Hegel argued that his own philosophical concept of spirit rendered transparent what was only obscurely represented in the Christian concept of the Trinity, thus revealing the philosophical truth of religion as fully "known."

In contrast to Kant's rational faith, Hegel's rational religion posits that religion's modern role is to express and nurture spirit in its most individual forms, rather than explaining reality. For Hegel, there is no place for faith in opposition to knowledge; instead, faith takes forms such as trust in close individuals or in one's time and place. According to his philosophical interpretation, Christianity does not demand faith in any doctrine not fully justifiable by reason, leaving a religious community free to minister to individual needs and celebrate the absolute freedom of spirit.

Hegel's Berlin Lectures (1821, 1824, 1827, 1831) offer his most extensive presentation of Christianity, which he termed the "consummate," "absolute," or "revelatory" religion. Transcripts show him continuously refining his exposition, deepening the interpretation of Christianity first presented in the Phenomenology.

Regarding interpretation, Walter Jaeschke questions whether Martin Luther would have recognized Hegel's claim to Protestantism. While Hegel embraced the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers with his concept of spirit, he rejected core Lutheran doctrines like sola gratia and sola scriptura. He affirmed Protestantism's "fundamental principle" as "the obstinacy that does honor to mankind, to refuse to recognize in conviction anything not ratified by thought," leading Frederick Beiser to describe Hegel's theology as effectively "the very opposite of Luther's." Despite his sincere profession of Lutheranism, Hegel's concept of God, which differs from both theistic and deistic views and aligns with St. Anselm's classical definition of God as "that of which nothing greater can be conceived," can only be articulated through the philosophical terms of spirit and his unique logical vocabulary. This distinctive articulation of Christianity remained a subject of intense debate during and after his lifetime.

3.7. Philosophy of History

For Hegel, "history is central to his conception of philosophy." He believed philosophy is only possible if it is historical, requiring the philosopher to be aware of the origins, context, and development of doctrines. This marked a "revolution in the history of philosophy." Although some categorize him as a historicist, Beiser excludes Hegel from the German historicist tradition because Hegel prioritized the philosophy of history over the epistemological justification of history as a science. Against the relativistic implications of narrowly construed historicism, Hegel's metaphysics of spirit provides an internal telos to history: the self-consciousness of freedom, which allows for measuring and assessing progress. The more this awareness permeates a culture, the more advanced Hegel deemed it to be.

Because freedom is the essence of spirit, its developing self-awareness is a progression in both truth and political life. Thinking necessitates an "instinctive belief" in truth, and the history of philosophy, as Hegel describes it, is a progressive sequence of "system-identifying" concepts of truth. Whether Hegel is a historicist depends on definition, but history's importance in his philosophy is undeniable.

German has two words for "history": Historie (narrative organization of empirical material) and Geschichte (underlying developmental logic of deeds and events). Hegel adopted the latter for his historical writings, aiming for a properly universal or philosophical history. He contended that humans are uniquely historical creatures because they not only exist in time but also internalize temporal events, making them integral to human self-understanding and self-knowledge. This is why the history of philosophy is crucial to philosophy itself; later philosophers, building on their predecessors, can think thoughts impossible for earlier ones. For example, the concept of personhood now implies universality, rendering contradictory any interpretation that applies it only to some individuals.

In the introduction to his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, Hegel simplifies human history into three epochs:

- In the "Oriental" world, one person (the pharaoh or emperor) was free.

- In the Greco-Roman world, some people (moneyed citizens) were free.

- In the "Germanic" world (i.e., European Christendom), all persons are free.

In his discussion of the ancient world, Hegel offered a heavily qualified defense of slavery as a "transitional phase between the natural human existence and the truly ethical condition," where "the wrong is valid, so that the position it occupies is a necessary one." However, Hegel was clear that there is an unconditional moral demand to reject slavery, viewing it as incompatible with the rational state and the essential freedom of every individual.

Some commentators, notably Alexandre Kojève and Francis Fukuyama, have interpreted Hegel as claiming that history concludes once a fully universal concept of freedom is achieved. However, this is challenged by arguments that freedom can still expand in both scope and content. Since Hegel's time, the scope of freedom has broadened to include women, formerly enslaved or colonized peoples, the mentally ill, and LGBTQ+ individuals, among others. The International Bill of Human Rights further extends the concept of freedom beyond Hegel's original articulation. Additionally, while Hegel consistently presented philosophical histories as East-to-West narratives, scholars like J. M. Fritzman argue that this geographical bias is incidental to Hegel's core philosophy, suggesting that the movement of freedom may now be returning to the East, evidenced by developments in countries like India and South Africa.

4. Methodology: Dialectics, Speculation, Idealism

Hegel's philosophical approach is deeply rooted in his distinctive methodology, which he primarily characterized as "speculative" rather than solely "dialectical," although both terms are often associated with him. This methodology is intertwined with his idealism, asserting the primacy of Spirit or Mind in constituting reality and underpinning his famous dictum, "the rational is actual, and the actual is rational."

4.1. The Dialectical Method

While Hegel is widely credited with employing a "dialectical method," he himself primarily described his philosophy as "speculative" (spekulativ), using the term "dialectical" (Dialektik) "quite rarely" and typically to refer to the "self-negation of the determinations of the understanding (Verstand), when they are thought through in their fixedness and opposition." For Hegel, correct thinking involves a methodical interplay of three moments:

- (a) abstract and intellectual (verständig),

- (b) dialectical or negatively rational (negativvernünftig), and

- (c) speculative or positively rational (positivvernünftig).

For example, self-consciousness is a speculative concept because it involves the mind's self-contradictory role as both subject and object of the same act of cognition, simultaneously.

According to Beiser, if Hegel has any methodology, it is an "anti-methodology," designed to "suspend all methods." Hegel's concept of dialectic must be understood as referring to the concept of the object under investigation, emphasizing the "self-organization" and "inner necessity" of the subject matter, rather than an external method applied to it. Hegel's speculative procedure often makes his positions difficult to characterize because he frequently recasts disputes by demonstrating that their underlying dichotomies are false, thereby integrating elements from apparently opposing theories. This process, which Hegel calls "sublation" (aufheben), preserves what is true from contradictions, leading to their speculative overcoming.

The German verb aufheben carries three main senses:

- 'to raise, to hold, lift up';

- 'to annul, abolish, destroy, cancel, suspend'; and,

- 'to keep, save, preserve.'

Hegel typically uses the term in all three senses, particularly emphasizing the second and third, where apparent contradictions are speculatively resolved. He refers to what is sublated as a "moment" (das Moment), denoting "an essential feature or aspect of a whole conceived as a static system, and an essential phase in a whole conceived as a dialectical movement or process." When Hegel describes something as "contradictory," he means it is not independently self-sustaining and can only be comprehended as a moment of a larger whole.

4.2. Speculative Thinking

Hegel's speculative thinking aims to grasp the unity of opposites and the totality of reality. Unlike purely analytical or intellectual methods that fix terms and distinctions, speculative thought integrates understanding, dialectics, and positive reason into a single complex process. It goes beyond the mere identification of contradictions (the dialectical moment) to a deeper comprehension that reconciles and preserves opposing elements within a higher unity. This positive reason, or speculative moment, understands that contradictions are inherent to existence and drive its development. Thus, for Hegel, reason is ultimately "speculative," as it moves beyond finite determinations to grasp the infinite, unified truth.

4.3. Idealism

For Hegel, to conceive of the finite as a moment of the whole, rather than an independently self-determined entity, is to grasp it as idealized (das Ideelle). His idealism asserts that "finite entities are ideal (ideell): they depend not on themselves for their existence but on some larger self-sustaining entity [i.e., the whole] that underlies or embraces them." The terms "moment," "sublate," and "idealize" are characteristic of Hegel's account of idealism, representing stages of thought where the object becomes conceptually present, progressing from mere adumbration to full self-standing.

This phenomenological and conceptual analysis distinguishes Hegel's idealism from Kant's transcendental idealism and Berkeley's mentalistic idealism. In contrast to these positions, Hegel's idealism is compatible with realism and non-mechanistic naturalism. It rejects empiricism as an a priori account of knowledge but is not opposed to the philosophical legitimacy of empirical knowledge. Hegel's idealistic contention, which he claims to demonstrate, is that being itself is rational. While "absolute idealism" is often used to describe his philosophy, Hegel himself rarely used this moniker, which was more commonly associated with Schelling at the time. Hegel famously declared, "every philosophy is essentially idealism," based on the assumption that conceptualization is present at all cognitive levels. To deny this would undermine trust in the conceptual capacities necessary for objective knowledge, leading to total skepticism. Thus, according to Robert Stern, Hegel's idealism "amounts to a form of conceptual realism, understood as 'the belief that concepts are part of the structure of reality."

4.4. Thesis-antithesis-synthesis

The terminology of "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis" is often used to describe Hegel's dialectical method, but this characterization is largely inaccurate and has been broadly discredited by scholars. This three-step formula, primarily developed by Fichte, was popularized by Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus in accounts of Hegel's philosophy. However, as Walter Kaufmann famously noted, Hegel himself "never once used these three terms together to designate three stages in an argument or account in any of his books," and their application "impede any open-minded comprehension of what he does by forcing it into a scheme which was available to him and which he deliberately spurned."

More accurately, this account is a "partial comprehension that requires correction." While it correctly identifies that "truth emerges from error" through historical development, implying a "holism in which partial truths are progressively corrected so that their one-sidedness is overcome," it distorts the process by suggesting a rigid, external method. The "thesis" and "antithesis" are not "alien" to one another, and the so-called "dialectical method" is not an external procedure that can be "applied" to a subject matter. Rather, as Stephen Houlgate argues, any "method" in Hegel's philosophy is strictly immanent, emerging from a thoughtful immersion in the subject matter itself. If this leads to dialectics, it is because a contradiction exists within the object itself, not because of an imposed methodological framework.

5. Legacy and Influence

Hegel's philosophy has had an immense and varied impact on subsequent intellectual history, shaping numerous philosophical movements and influencing a wide array of thinkers across different traditions.

5.1. Schools of Thought

Hegel's early influence in Germanic philosophy is sometimes presented as a division into two opposing camps: the Right Hegelians and the Left Hegelians. The Right Hegelians, allegedly direct disciples at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, advocated for Protestant orthodoxy and the political conservatism of the post-Napoleon Restoration. However, this interpretation has been questioned by recent studies. The Left Hegelians, or Young Hegelians, interpreted Hegel in a revolutionary sense, leading to advocacy for atheism in religion and liberal democracy in politics. While the Right Hegelians were "quickly forgotten," the Left Hegelians, including influential thinkers like Feuerbach, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels, "remained exceedingly influential," primarily through the Marxist tradition.

The primary thrust of the Young Hegelians' criticism is concisely expressed in the eleventh of Marx's "Theses on Feuerbach" (1845): "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it." In the twentieth century, a Hegelian-inflected interpretation of Marx was further developed by critical theorists of the Frankfurt School. This resurgence of interest in Hegel among Marxists was driven by the rediscovery of Hegel as a philosophical progenitor of Marxism, a renewed appreciation for his historical perspective, and an increasing recognition of his dialectical method. György Lukács's History and Class Consciousness (1923) played a significant role in reintroducing Hegel into the Marxist canon.

Hegel's influence extended beyond Germany. In late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century England, British idealism, a school propounding a version of absolute idealism, engaged directly with his texts, with prominent members including J. M. E. McTaggart, R. G. Collingwood, and G. R. G. Mure.

5.2. Influence on Specific Thinkers

Hegel's direct and indirect influence can be seen in a diverse array of prominent philosophers and thinkers. Beyond Marxists, philosophers such as John Dewey, Jacques Derrida, Adorno, and Gadamer selectively developed Hegelian ideas into their own philosophical programs. In contrast, others, including Arthur Schopenhauer, Søren Kierkegaard, Bertrand Russell, G. E. Moore, and Michel Foucault, developed their positions in explicit opposition to Hegel's system. In theology, Hegel's thought notably impacted the work of Karl Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. These figures represent only a small sample of the many who engaged deeply with Hegel's philosophy.

5.3. Influence on Political and Social Thought

Hegel's contributions to political philosophy, particularly his views on the state, freedom, and civil society, have profoundly influenced subsequent political and social theories. His philosophy of objective spirit, which conceptualizes the state as the "institutionalization of freedom," argues for a rational state that balances individual liberty with a larger collective good. He critiqued radical individualism and the perceived limitations of pure civil society, advocating for the state as a higher ethical unity that integrates its citizens.

Hegel's complex views on the state and historical progress have led to varied interpretations. While some critics argue his work lends itself to authoritarian or conservative readings, others, such as Herbert Marcuse, contend that Hegel was not an apologist for any state simply because it existed, but rather insisted that the state must always be rational. His emphasis on historical development and the unfolding of reason has influenced various political theories, from Marxism's historical materialism to later concepts of progress and social change.

5.4. Reception in Different Countries

The reception of Hegel's philosophy varied significantly across different countries. In France, "French Hegel" became largely identified with the influential lectures of Alexandre Kojève (1933-1939), which emphasized the lord-bondsman dialectic (mistranslated by Kojève as "master-slave") and Hegel's philosophy of history. This perspective, focusing on The Phenomenology of Spirit, reacted against earlier French interpretations that identified Hegelianism with the more systematic Encyclopedia. After 1945, this "dramatic" Hegelianism, centered on historical becoming through conflict, was seen as compatible with existentialism and Marxism. By confining the dialectic to history, thinkers like Jean Wahl, Kojève, and Jean Hyppolite effectively presented Hegel as offering "a philosophical anthropology instead of a general metaphysics," with desire becoming a central point of intervention. This reading shaped the thought of Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan, and Georges Bataille. Kojève's interpretation of the "master-slave dialectic" also influenced the feminism of Simone de Beauvoir and the anti-racist and anti-colonial work of Frantz Fanon.

In the United States, the influence of Hegel on American Pragmatism unfolded in three main periods, as documented by Richard J. Bernstein. The first appeared in early issues of The Journal of Speculative Philosophy (founded 1867). The second is evident in the acknowledged influence on major figures such as John Dewey, Charles Sanders Peirce, and William James. John Dewey, for example, found in Hegel's thought a powerful "demand for unification" that "only an intellectualized subject-matter could satisfy," though he rejected Hegel's concept of absolute knowing.

The third period of influence is represented by John McDowell and Robert Brandom, sometimes referred to as the "Pittsburgh Hegelians." While they openly acknowledge Hegel's influence, they do not claim to explicate his views according to his own self-understanding, and are also influenced by Wilfrid Sellars. McDowell focuses on dispelling the "myth of the given" (the dichotomy between concept and intuition), while Brandom develops Hegel's social account of reason-giving and normative implication. These appropriations are examples of "non-metaphysical" readings of Hegel.

6. Criticism and Debate

Hegel's philosophy, methodology, and historical interpretations have been subject to extensive criticism and ongoing debate throughout history, from his contemporaries to modern philosophers.

6.1. Critiques of Methodology and System

Hegel's philosophy is often criticized for its complexity, perceived obscurity, and idiosyncratic terminology, making it notoriously difficult to understand. This difficulty was recognized even in his own day and persists into the 21st century. While Hegel himself was aware of his "obscurantism," he saw it as a necessary aspect of philosophical thinking that transcends the limitations of everyday thought and concepts. He argued that it is the "man on the street" who thinks abstractly by using concepts as fixed, unchangeable givens, whereas the philosopher thinks concretely by understanding concepts within their broader context, which can make philosophical language seem mysterious.

A major point of contention centers on Hegel's dialectical method. As noted, the popular "Thesis, antithesis, synthesis" formulation is a misrepresentation, originally attributed to Fichte and popularized by Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus, rather than Hegel. Critics argue that this misinterpretation simplifies and distorts the nuanced self-movement of concepts in Hegel's thought.

Arthur Schopenhauer, a contemporary and rival of Hegel at the University of Berlin, was one of his most vehement detractors. Schopenhauer despised Hegel's alleged historicism and decried his work as "obscurantism" and "pseudo-philosophy," famously calling it "the height of audacity in serving up pure nonsense, in stringing together senseless and extravagant mazes of words... a monument to German stupidity." This judgment stemmed from Hegel's rejection of traditional laws of thought in his Science of Logic, which Schopenhauer believed undermined rational discourse.

Søren Kierkegaard, an early critic of Hegel, challenged his concept of "absolute knowledge," deeming it arrogant for a human to claim such a unity. Kierkegaard argued that Hegel's system negated the importance of the individual in favor of the whole, writing that it "fantastically dissipates the concept existence" and abolishes being an individual man, leading speculative philosophers to confuse themselves with humanity at large, thereby becoming "something infinitely great, and at the same time nothing at all."

Modern analytic and positivistic philosophers have often targeted Hegel for what they consider the obscurity of his philosophy. Some, like Bertrand Russell, described him as the single most difficult philosopher to understand.

6.2. Critiques of Political and Social Views

Hegel's political and social philosophy has drawn significant criticism, particularly concerning his views on the state, freedom, and historical progress. Some critics allege that his work, particularly Elements of the Philosophy of Right, serves as an apologia for the existing power structures, specifically the Prussian state of his time, and contains potentially authoritarian or conservative interpretations.

George Santayana criticized Hegel for what he perceived as a "worship of power," suggesting that Hegel equated dominance with goodness, a system that "qualified its veneration for success by attributing success, in the future at least, to what could really inspire veneration."

Karl Popper, in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945), accused Hegel's system of being a thinly veiled justification for the rule of Frederick William III, arguing that Hegel saw the Prussian state of the 1830s as the ultimate goal of historical progress. Popper contended that Hegel's philosophy was a precursor to 20th-century totalitarianism, seeing his dialectics as a tool to legitimize any belief. However, this view has been criticized by scholars like Herbert Marcuse (in Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory), Walter Kaufmann, and Shlomo Avineri, who argue that Hegel did not advocate for any state simply because it existed, but rather for a state that was rational and embodied freedom. Joachim Ritter's Hegel and the French Revolution also offered a strong counter-argument to Popper's claims. Isaiah Berlin included Hegel among six "architects" of modern totalitarianism, alongside figures like Rousseau and Joseph de Maistre.

6.3. Critiques of Religious and Aesthetic Views

Hegel's interpretations of religion and art have also faced criticism. His philosophical reinterpretation of Christianity, for instance, which sought to make its doctrines transparently rational and emphasized the community's role in celebrating the absolute freedom of spirit, was seen by some, like Lutheran scholars, as fundamentally departing from traditional Christian theology.

Regarding his aesthetics, while Hegel asserted that "artistic beauty reveals absolute truth through perception," his view that art's sensory media could never fully convey transcendent truths led to the misinterpretation by figures like Benedetto Croce that Hegel believed art was "dead."

The psychologist Carl G. Jung offered one of the harshest criticisms, seemingly accusing Hegel of mental illness, writing that "A philosophy like Hegel's is a self-revelation of the psychic background and, philosophically, a presumption. Psychologically it amounts to an invasion by the Unconscious. The peculiar, high-flown language Hegel uses bears out this view -- it is reminiscent of the megalomaniac language of schizophrenics, who use terrific, spellbinding words to reduce the transcendent to subjective form, to give banalities the charm of novelty, or pass off commonplaces as searching wisdom. So bombastic a terminology is a symptom of weakness, ineptitude, and lack of substance."

Despite persistent criticisms, Hegel's philosophy experienced a significant renaissance in the latter half of the 20th century. This was driven by renewed interest in his historical perspective and dialectical method, particularly among philosophically oriented Marxists, as well as a new wave of scholarship (e.g., from the Hegel Society of America and German scholars like Otto Pöggeler and Walter Jaeschke) that sought to read Hegel's works without prior preconceptions, leading to diverse and ongoing re-evaluations.

7. Publications

Hegel published four major works during his lifetime, which laid the foundation for his expansive philosophical system. Additionally, many of his significant contributions, particularly his detailed explorations of art, religion, and history, were compiled and published posthumously from his students' lecture notes.

7.1. Major Published Works

- The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807): His first major work, outlining the evolution of consciousness from sense-perception to absolute knowing.

- The Science of Logic (Wissenschaft der LogikGerman, 3 vols., 1812, 1813, and 1816; Book I revised 1831): Sometimes called the "Greater Logic," this work forms the logical and metaphysical core of his philosophy.

- Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften im GrundrisseGerman, 1817; revised 1827 and 1830): A summary of his entire philosophical system, often referred to as the "Lesser Logic" in its first volume.

- Elements of the Philosophy of Right (Grundlinien der Philosophie des RechtsGerman, 1821): His political philosophy, also known as Philosophy of Right.

7.2. Lecture Series and Unpublished Manuscripts

Throughout his career, Hegel delivered numerous lecture series, which, though not formally published by him, were meticulously compiled by his students and released posthumously. These provide extensive insights into various aspects of his philosophy.

- Early Unpublished Manuscripts (Bern, 1793-96; Frankfurt am Main, 1797-1800; Jena, 1801-07):**

- Nuremberg (1808-16):**

- Heidelberg (1816-18):**

- Berlin Lecture Series (1818-31):**

8. Related Entries

- Absolute idealism

- Aristotle

- British idealism

- Dialectics

- Elements of the Philosophy of Right

- Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

- Geist

- German idealism

- German Romanticism

- History of philosophy

- Immanuel Kant

- Jakob Böhme

- Johann Gottlieb Fichte

- Karl Marx

- Lectures on Aesthetics

- Lectures on the Philosophy of History

- Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion

- Lord-bondsman dialectic

- Philosophy of history

- Political philosophy

- The Phenomenology of Spirit

- The Science of Logic

- Young Hegelians

- Wilhelm Ludwig Sayn-Wittgenstein

- Karl Ludwig von Haller

- August von Kotzebue

- Kierkegaard

- Arthur Schopenhauer

- John Dewey

- Robert Brandom

- John McDowell

- Francis Fukuyama

- Alexandre Kojève

- Frederick C. Beiser

- Robert Stern (philosopher)

- Terry Pinkard

- Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus

- Walter Kaufmann (philosopher)

- Isaiah Berlin

- Karl Popper

- Herbert Marcuse

- Giovanni Gentile

- History

- State

- Freedom

- Civil society

- Family

- Religion

- Art

- Philosophy

- Logic

- Metaphysics

- Epistemology

- Idealism

- Romanticism

- Enlightenment

- French Revolution

- Napoleonic Wars

- Constitutional monarchy

- Absolute monarchy

- Democracy

- Aristocracy

- Hylomorphism

- Positive liberty

- Negative liberty

- Human rights

- Atheism

- Lutheranism

- Protestantism

- Dialectics

- Teleology

- Immanence

- Skepticism

- A priori and a posteriori

- Mind-body problem

- Existentialism

- Marxism

- Frankfurt School

- Pragmatism

- Feuerbach

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Jacques Derrida

- Theodor W. Adorno

- Hans-Georg Gadamer

- Sartre

- Michel Foucault

- Karl Barth

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer

- Benedetto Croce

- Johann Gottlieb Fichte

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

- Baruch Spinoza

- Adam Smith

- Johann Gottfried von Herder

- Sittlichkeit

- Weltseele

- Aufheben

- Recht

- Bildungsroman

- Transcendental deduction

- Conceptual realism

- American Pragmatism

- Transcendental idealism

- Christian Wolff (philosopher)

- Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten

- Ernst Gombrich

- Incarnation

- Resurrection

- Trinity

- Sola gratia

- Sola scriptura

- Priesthood of all believers

- The Open Society and Its Enemies

- Reason and Revolution

- Giovanni Gentile

- Jacques Lacan

- Simone de Beauvoir

- Frantz Fanon

- Mind

- Spirit

- Self-consciousness

- Freedom

- Justice

- Moral philosophy

- Ethics

- Law

- Consciousness

- Psychology

- Anthropology

- Sociology

- Family

- Civil society

- State

- Nation-state

- Constitutionalism

- Revolution

- War

- Imperialism

- Colonialism

- Racism

- Slavery

- Haitian Revolution

- Human rights

- International Bill of Human Rights

- Progress

- World history

- Epoch

- Unity

- Contradiction

- Totality

- Self-determination

- Absolute knowing

- Art

- Religion

- Philosophy

- Aesthetics

- Theology

- Monism

- Pantheism

- Atheism

- Mysticism

- Dogmatism

- Truth

- Knowledge

- Experience

- Intuition

- Representation

- Concept

- Idea

- Being

- Essence

- World spirit