1. Overview

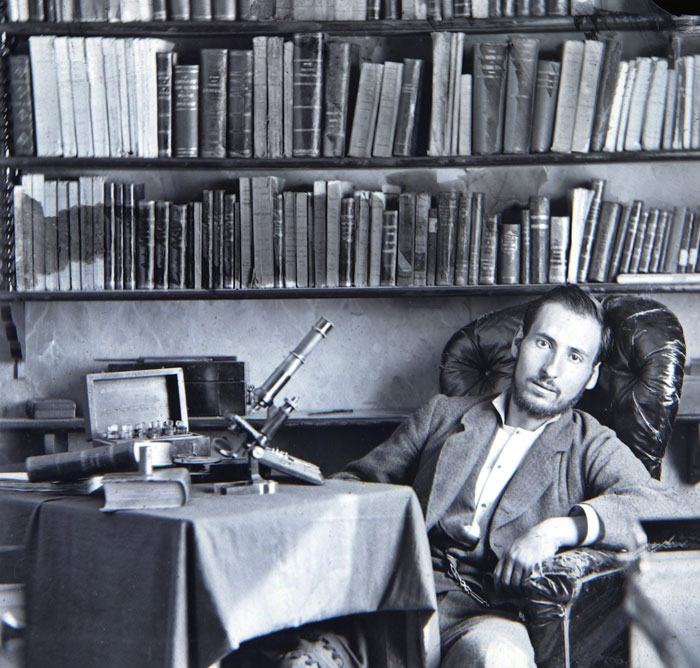

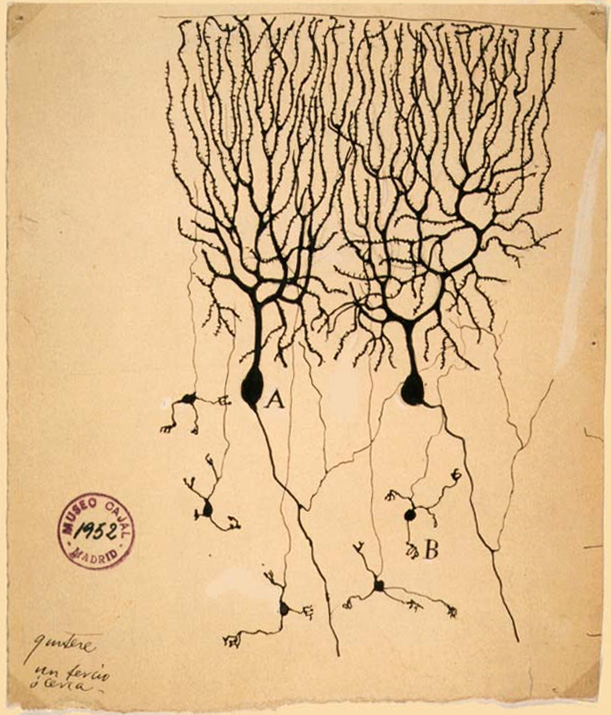

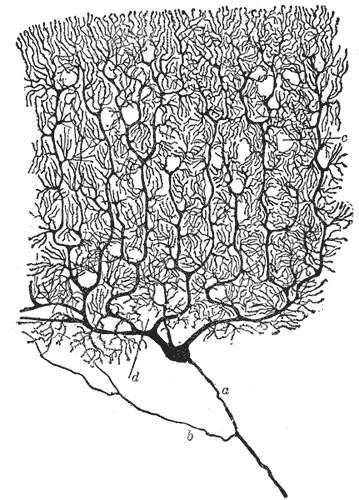

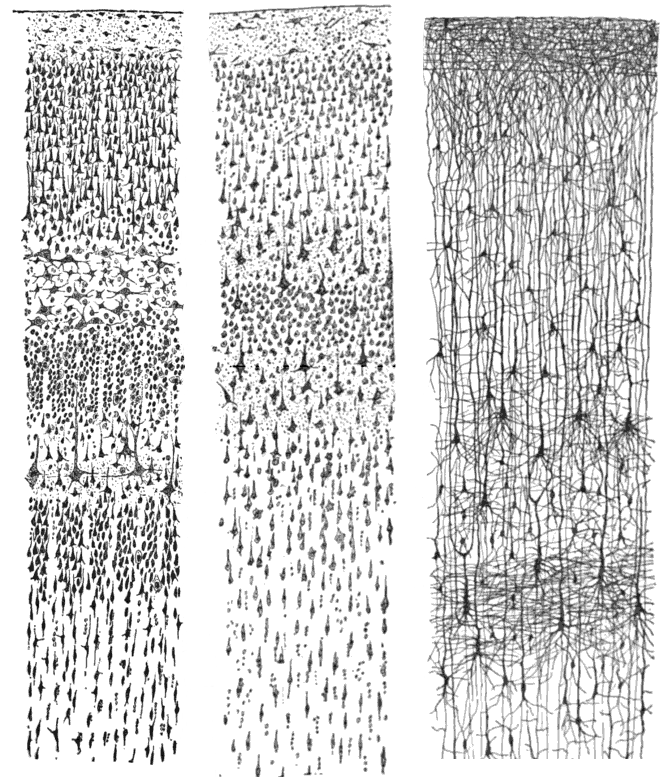

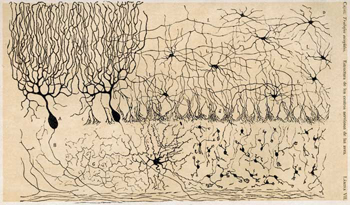

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Santiago Ramón y Cajalsanˈtjaɣo raˈmon i kaˈxalSpanish; May 1, 1852 - October 17, 1934) was a pioneering Spanish neuroscientist, pathologist, and histologist who specialized in neuroanatomy and the central nervous system. Often regarded as the father of modern neuroscience, he was the first Spaniard to receive a scientific Nobel Prize. He was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 with Camillo Golgi for their groundbreaking work on the structure of the nervous system. Ramón y Cajal's original investigations into the microscopic structure of the brain laid the foundational concepts of modern neuroscience. His hundreds of meticulously detailed drawings illustrating the intricate arborization (tree-like growth) of brain cells are celebrated for their artistic quality and remain widely used for educational and training purposes in neuroscience to this day.

2. Biography

Santiago Ramón y Cajal's life journey was marked by early rebelliousness, a strong artistic inclination, and a relentless pursuit of scientific understanding that ultimately revolutionized the field of neuroscience.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was born on May 1, 1852, in Petilla de Aragón, a town in Navarre, Spain. His parents were Justo Ramón and Antonia Cajal. As a child, he frequently changed schools due to his rebellious and anti-authoritarian behavior. An notable example of his precociousness and defiance occurred at the age of eleven in 1863, when he was imprisoned for destroying a neighbor's yard gate with a homemade cannon. Despite his father's disapproval and lack of encouragement, Ramón y Cajal was a keen painter, artist, and gymnast. These artistic talents, though initially unappreciated by his father, would later prove crucial to his success as a scientific illustrator. His father, seeking to instill discipline and stability, apprenticed him to a shoemaker and a barber. However, Ramón y Cajal's interest in medicine was sparked in the summer of 1868 when his father took him to graveyards to find human remains for anatomical study. His early sketches of bones solidified his decision to pursue medical studies. He subsequently attended the medical school of the University of Zaragoza, where his father served as an anatomy teacher, and he graduated in 1873 at the age of 21.

2.2. Military Service

Following his graduation, Ramón y Cajal served as a medical officer in the Spanish Army. In 1874-1875, he participated in an expedition to Cuba during the Ten Years' War. During his service in the Cuban jungles, he contracted severe illnesses, including malaria and tuberculosis. To aid his recovery, he spent time recuperating in the spa-town of Panticosa in the Pyrenees mountain range after returning to Spain in June 1875.

2.3. Early Career and Professorships

Ramón y Cajal obtained his doctorate in medicine in Madrid in 1877. Two years later, in 1879, he was appointed director of the Anatomical Museum at the University of Zaragoza. He worked at the University of Zaragoza until 1883, when he was awarded the position of anatomy professor at the University of Valencia. His initial research at these universities focused on the pathology of inflammation, the microbiology of cholera, and the structure of epithelial cells and tissues.

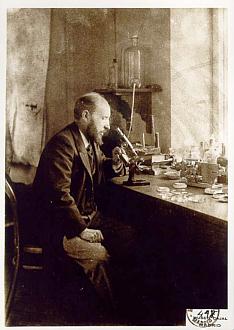

In 1887, Ramón y Cajal moved to Barcelona to take up a professorship. It was there that he first encountered Golgi's method, a revolutionary cell staining technique developed by Camillo Golgi. This method, which uses potassium dichromate and silver nitrate, selectively stains a small number of neurons a dark black, leaving surrounding cells transparent. Ramón y Cajal significantly improved upon this technique, making it central to his subsequent research. It allowed him to focus his attention on the densely intertwined neurons of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), which had previously been nearly impossible to inspect using standard microscopic methods. During this period, he produced extensive and highly detailed drawings of neural material from various species and most major regions of the brain.

In 1892, he became a professor at Madrid. His academic career continued to advance, and in 1899, he was appointed director of the Instituto Nacional de Higiene (National Institute of Hygiene). In 1922, he founded the Laboratorio de Investigaciones BiológicasSpanish (Laboratory of Biological Investigations), which was later renamed the Cajal Institute (Instituto CajalSpanish).

2.4. Marriage and Family

In 1879, Santiago Ramón y Cajal married Silveria Fañanás García. Together, they had twelve children: seven daughters and five sons.

2.5. Death

Santiago Ramón y Cajal died in Madrid on October 17, 1934, at the age of 82. He remained dedicated to his scientific work, continuing his investigations even on his deathbed.

3. Political and Religious Views

Ramón y Cajal held distinct personal philosophies that encompassed his political leanings and the evolution of his religious beliefs throughout his life.

3.1. Political Ideology

In 1877, at the age of 25, Ramón y Cajal joined a Masonic lodge, reflecting his early liberal political inclinations. He is considered a regenerationist, a movement that sought to revitalize Spain, and was a staunch Spanish nationalist and centralist. In this context, he viewed non-Spanish nationalisms, such as Catalan nationalism and Basque nationalism, as separatist movements.

Despite his centralist views, he accepted the Statute of Núria and acknowledged that classes could be taught in the Catalan language at the university level, though he reportedly felt uncomfortable with this arrangement. In 1937, amidst the Spanish Civil War, he implicitly positioned himself with the national-Catholic rebels against the Second Spanish Republic. In a statement published in the Gaceta de Melilla, he echoed the need for an "iron surgeon" to impose the moral unity of the Peninsula, suggesting a forceful solution to merge what he saw as "dissonances and spiritual stridor" into a "grandiose symphony" for the homeland.

3.2. Religious Beliefs

Ramón y Cajal's spiritual journey evolved over time. He was initially described as an agnostic in his early career. However, he later expressed regret for having left organized religion and ultimately became convinced of a belief in God as a creator. He openly stated this belief during his first lecture before the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences. Despite his agnostic phase, he used the term "soul" in his scientific discussions "without any shame," indicating a nuanced view that integrated scientific inquiry with a broader sense of human experience. He believed that science could reveal the "incomparable beauty of the work of God and the eternal laws established by Him," seeing the study of nature as a profound form of reverence for the divine.

4. Scientific Contributions and Theories

Ramón y Cajal's scientific work was revolutionary, fundamentally changing the understanding of the nervous system and laying the groundwork for modern neuroscience. His contributions were characterized by meticulous observation, innovative techniques, and exceptional artistic skill.

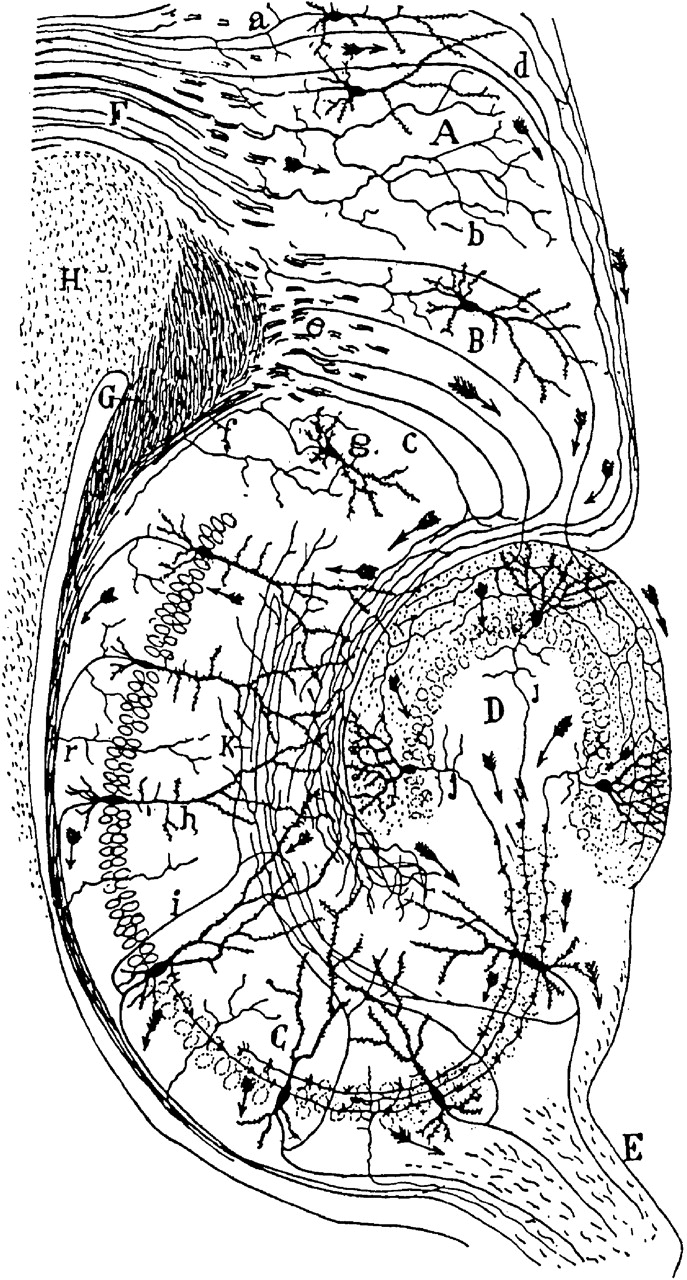

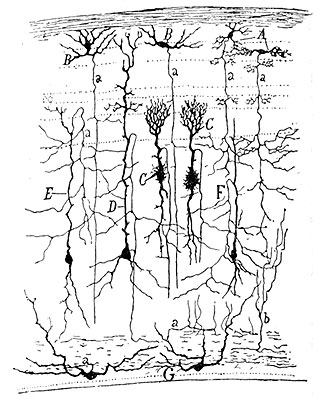

4.1. Neuroscience and the Neuron Doctrine

Ramón y Cajal made several major contributions to neuroanatomy. His interest in the insect visual nervous system, spurred by the discoveries of Frederick C. Kenyon, led him to explore the vast variety of neuron types. His most significant contribution was the formulation of the neuron doctrine. This theory proposed that the nervous system is composed of billions of discrete, individual cells called neurons, which communicate with each other at specialized junctions later termed synapses by Charles Sherrington in 1897. Each neuron, according to Cajal, possesses a cell body, dendrites, and an axon, exhibiting a distinct cell polarity.

This concept directly challenged the prevailing reticular theory, championed by his contemporary and Nobel co-recipient, Camillo Golgi. Golgi believed that nerve cells formed a continuous, interconnected network or reticulum, a single system without gaps. Ramón y Cajal's extensive use and improvement of Golgi's staining method, which randomly stained only a few neurons, allowed him to observe the intricate structures of individual neurons with unprecedented clarity. Through these observations, he provided definitive experimental evidence that the relationship between nerve cells was not continuous but rather contiguous, meaning there were distinct gaps between them. This finding provided crucial support for what Heinrich Wilhelm Gottfried von Waldeyer-Hartz would name the "neuron theory," now universally accepted as the foundation of modern neuroscience. Ramón y Cajal is considered by some to be the first "neuroscientist," having stated in 1894 to the Royal Society of London that "The ability of neurons to grow in an adult and their power to create new connections can explain learning," a statement considered the origin of the synaptic theory of memory. Later, the advent of electron microscopy conclusively demonstrated the independent cell membranes of individual neurons, fully supporting Ramón y Cajal's theory and refuting Golgi's reticular theory.

4.2. Key Discoveries

Beyond the neuron doctrine, Ramón y Cajal made several other significant discoveries:

- Axonal Growth Cone:** He discovered the axonal growth cone, the motile tip of a growing axon, and experimentally demonstrated that axons grow through this cone. He understood that nerve cells could detect chemical signals, a process known as chemotaxis, which guided their growth direction.

- Dendritic Spines:** He was an advocate for the existence of dendritic spines, small protrusions on dendrites that significantly increase the surface area available for synaptic contacts. Although he did not fully recognize them as the primary sites of contact from presynaptic cells, his observations were foundational. His student, Rafael Lorente de Nó, furthered this work, studying input-output systems and contributing to cable theory and early circuit analysis of neural structures.

- Interstitial Cell of Cajal (ICC):** He discovered a new type of cell, subsequently named the interstitial cell of Cajal (ICC). These cells are found interspersed among neurons within the smooth muscles lining the gut. They function as the generator and pacemaker of the slow waves of contraction that propel material along the gastrointestinal tract, and they mediate neurotransmission from motor neurons to smooth muscle cells.

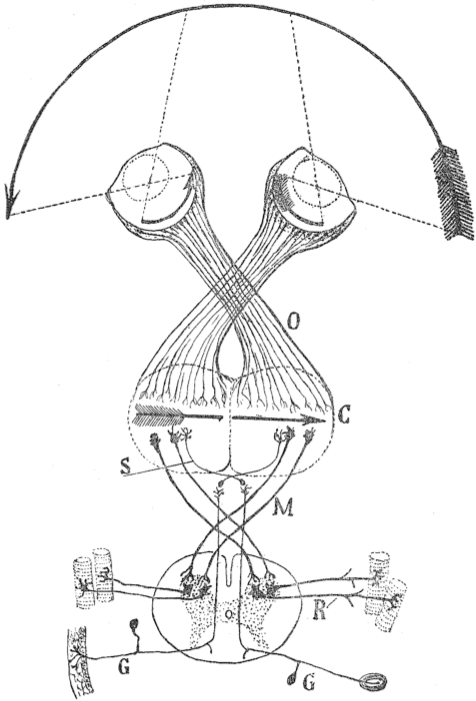

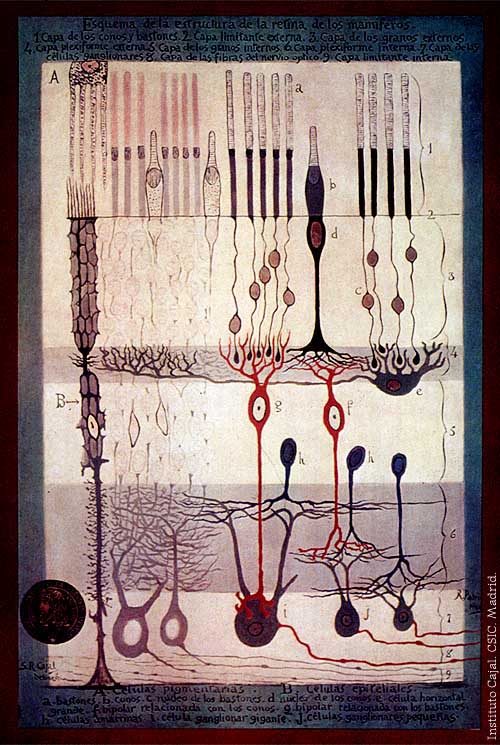

- Visual Map Theory:** In his 1898 work, Ramón y Cajal developed a visual map-based theory that offered an evolutionary explanation for the decussation of nerve fibers and the optic chiasm. This theory explained how visual information from each eye crosses over to the opposite side of the brain.

- Cortical Pyramidal Cells:** In his 1894 Croonian Lecture, Ramón y Cajal used an extended metaphor to suggest that cortical pyramidal cells may become more elaborate over time, much like a tree grows and extends its branches, implying neural plasticity.

- Psychological Phenomena:** He also studied psychological phenomena, including hypnotic suggestion for pain alleviation, which he used to assist his wife during labor. Unfortunately, a book he had written on these topics was lost during the Spanish Civil War.

4.3. Artistic Approach to Science

Ramón y Cajal's early artistic talents, though initially discouraged by his father, became an indispensable asset in his scientific career. He was a keen painter and artist, and this inclination contributed significantly to his success as a morphologist and anatomist. He produced extensive, detailed drawings of neural structures and their connectivity, covering many species and most major regions of the brain. These hundreds of drawings, illustrating the fine arborization of brain cells, are celebrated for their scientific accuracy and artistic quality. They played a crucial role in advancing the understanding and teaching of neuroscience and are still used for educational and training purposes today. The synergy between his artistic talent and scientific inquiry allowed him to visualize and depict the complex architecture of the nervous system with unparalleled clarity.

5. Awards and Honors

Santiago Ramón y Cajal received numerous significant recognitions and accolades throughout his distinguished scientific career, reflecting the profound impact of his work.

5.1. Nobel Prize

The most renowned distinction awarded to Ramón y Cajal was the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906. He shared this prestigious award with the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system." However, the joint award caused some controversy because Golgi, a staunch proponent of the reticular theory, fundamentally disagreed with Ramón y Cajal's view of the neuron doctrine. Their differing scientific interpretations were even highlighted during their respective Nobel lectures. It is also noted that Ramón y Cajal did not cite the earlier work of Norwegian scientist Fridtjof Nansen, who had established the contiguous nature of nerve cells in his studies of certain marine life.

5.2. Academic Honors and Memberships

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Ramón y Cajal received a multitude of academic honors. He was awarded honorary doctorates in medicine from prestigious institutions such as Cambridge University and Würzburg University. He also received an honorary Doctor of Philosophy degree from Clark University. He was recognized internationally as an International Member of both the United States National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society. His other notable awards include the Croonian Medal from the Royal Society in 1894 and the Helmholtz Medal in 1904.

6. Impact and Legacy

Santiago Ramón y Cajal's work left a profound and lasting influence on the fields of neuroscience, medicine, and even culture and art, establishing him as one of the most significant figures in the history of science.

6.1. Impact on Neuroscience and Medicine

Ramón y Cajal's foundational discoveries, particularly the neuron doctrine, irrevocably shaped modern neuroscience and medicine. His meticulous anatomical descriptions and theories provided the conceptual framework for understanding the brain's cellular organization, which remains central to neuroscientific research today. His legacy is actively maintained through institutions like the Cajal Institute (Instituto CajalSpanish), which he founded as the Laboratorio de Investigaciones BiológicasSpanish. Furthermore, the Spanish Ministry of Science continues to honor his memory by awarding over two hundred postdoctoral scholarships annually, known as "Ayudas a contratos Ramón y Cajal" (Ramón y Cajal contracts), to mid-career scholars across various fields of knowledge since 2001.

6.2. Cultural and Artistic Recognition

Ramón y Cajal's life and work have been widely commemorated through various cultural and artistic initiatives:

- Portraits and Statues:** In 1906, Joaquín Sorolla painted Cajal's official portrait to celebrate his Nobel Prize win. A statue created by sculptor Mariano Benlliure was installed in 1924 in the Paraninfo building at the School of Medicine of the University of Zaragoza. In 1931, a 9.8 ft (3 m) high full-body statue on a narrow pedestal, created by Chilean medical student Lorenzo Domínguez, was unveiled in Madrid, Spain.

- Exhibitions:**

- The first major exhibition of Cajal's scientific drawings opened in Madrid, Spain, in 2003. Titled Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852-2003) Ciencia y Arte, it featured hundreds of restored original drawings, micrographic slides, and personal photographs.

- Since 2014, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, USA, has hosted an ongoing exhibition of original Ramón y Cajal drawings in the John Porter Neuroscience Research Center. This exhibition, a collaboration with the Cajal Institute, also features contemporary artwork inspired by Cajal's drawings by artists Rebecca Kamen and Dawn Hunter, which are on permanent display.

- A selection of Cajal's scientific drawings, personal photos, oil paintings, and pastel drawings were curated into the 14th Istanbul Biennial, Saltwater, held in Istanbul, Turkey, in 2015.

- The exhibition Fisiología de los Sueños. Cajal, Tanguy, Lorca, Dalí... (Physiology of Dreams. Cajal, Tanguy, Lorca, Dalí...) at the University of Zaragoza (2015-2016) centered on Cajal's work, exploring the influence of histological drawings on Surrealism.

- In 2016, Cajal's work was featured in the inaugural exhibition, Architecture of Life, for the re-opening of the University of California's Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

- The NIH and the CSIC (Cajal Institute) held collaborative symposiums honoring Cajal in 2015 and 2017. The 2015 symposium, Bridging the Legacy of Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a symposium honoring the father of modern neuroscience, featured Dr. Rafael Yuste as keynote speaker. The 2017 symposium, New Opportunities for NIH-CSIC Collaboration, hosted Dawn Hunter's "Cajal Inventory" art project, which recreated Cajal's drawings and surreal portraits.

- A major exhibition titled The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal toured North America from 2017 to 2019, visiting institutions like the Weisman Art Museum (Minneapolis), the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery (Vancouver), the Grey Art Museum (New York City), the MIT Museum (Cambridge), and the Ackland Art Museum (Chapel Hill). An accompanying book, The Beautiful Brain, was published by Abrams.

- In 2019, the University of Zaragoza hosted another exhibition, Santiago Ramón y Cajal. 150 years at the University of Zaragoza.

- From November 2020 to December 2021, the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (National Museum of Natural Sciences) in Madrid, Spain, displayed an exhibition featuring Cajal's scientific drawings, photographs, scientific equipment, and personal objects from the Legado Cajal (Cajal Legacy).

- Other Commemorations:**

- The asteroid 117413 Ramonycajal was named after him by Juan Lacruz in 2005.

- In 2007, sculptures of Severo Ochoa and Santiago Ramón y Cajal, created by Víctor Ochoa, were unveiled at the Spanish National Research Council central headquarters in Madrid.

- The Santiago Ramón y Cajal Museum opened in 2013 in Ayerbe, Huesca, Spain, located in his childhood home where he lived for ten years.

- In 2020, The Cajal Embroidery Project, involving over 75 volunteers across six countries, created 81 hand-stitched panels of Ramón y Cajal's images, which were showcased by The Lancet Neurology.

- In 2017, UNESCO recognized Cajal's Legacy, which had been preserved in a museum from 1945 to 1989, as a World Heritage treasure. There has been a call for a dedicated museum to commemorate and celebrate his discoveries.

- Project Encephalon organized "Cajal Week" from May 1 to May 7, 2021, to celebrate his 169th birth anniversary.

- Media and Literature:**

- A Spanish TV mini-series titled Ramón y Cajal: Historia de una voluntad (Ramón y Cajal: History of a Will) was created in 1982.

- A short documentary about him by REDES is available on YouTube.

- An English-language biography, The Brain In Search Of Itself, was published in 2022.

7. Publications

Santiago Ramón y Cajal was a prolific writer, publishing more than 100 scientific works and articles in Spanish, French, and German. His extensive written contributions laid the foundational texts for modern neuroscience.

7.1. Scientific Works

His major scientific books and articles include:

- Rules and advice on scientific investigation

- Histology

- Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system

- Manual of normal histology and micrographic technique

- Elements of histology

- Manual de Anatomia Patológica General (Handbook of general Anatomical Pathology), 1890 (fourth edition 1905)

- Die Retina der Wirbelthiere: Untersuchungen mit der Golgi-cajal'schen Chromsilbermethode und der ehrlich'schen Methylenblaufärbung (Retina of vertebrates), 1894

- Les nouvelles idées sur la structure du système nerveux chez l'homme et chez les vertébrés (New ideas on the fine anatomy of the nerve centres), 1894

- Beitrag zum Studium der Medulla Oblongata: Des Kleinhirns und des Ursprungs der Gehirnnerven, 1896

- Estructura del quiasma óptico y teoría general de los entrecruzamientos de las vías nerviosas (Structure of the Chiasma opticum and general theory of the crossing of nerve tracks), 1898

- Comparative study of the sensory areas of the human cortex, 1899

- Textura del sistema nervioso del hombre y los vertebrados (Textbook on the nervous system of man and the vertebrates), 1899-1904 (translated to French as Histologie du système nerveux de l'homme & des vertébrés in 1909, and English as Texture of the Nervous System of Man and the Vertebrates in 2002)

- Studien über die Hirnrinde des Menschen v.5 (Studies about the meninges of man), 1906

- Advice for a Young Investigator, 1897 (translated to English in 1999)

- Contribución al conocimiento de los centros nerviosos de los insectos, 1915

- Recuerdos de mi Vida (Memories of my Life), his autobiography, 1917 (published 1937)

7.2. Other Writings

In addition to his scientific output, Ramón y Cajal also ventured into other literary forms. In 1905, he published five science fiction stories under the pseudonym "Dr. Bacteria," collectively titled "Vacation Stories."