1. Overview

Hürrem Sultan, born Aleksandra or Anastazja Lisowska around 1504 in Ruthenia (modern-day Ukraine), rose from enslavement to become the chief consort and legal wife of Suleiman the Magnificent, the longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Captured by Crimean Tatars and brought to Constantinople, her intelligence, charm, and striking red hair quickly earned her Suleiman's favor within the Ottoman Imperial Harem. Breaking centuries of Ottoman tradition, Suleiman not only married Hürrem, freeing her from slavery, but also created the unique title of "Haseki Sultan" for her, elevating her status significantly above previous consorts.

Her unprecedented influence extended beyond the harem into the political sphere, where she served as a trusted advisor to Suleiman on state affairs and engaged in diplomatic correspondence with foreign rulers like Sigismund II Augustus of Poland. Hürrem's rise marked the beginning of the "Sultanate of Women", an era where imperial consorts wielded considerable political power. Despite controversies surrounding her alleged involvement in the downfall of rivals like Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha and Şehzade Mustafa, Hürrem also dedicated herself to extensive philanthropic endeavors, commissioning major architectural complexes, hospitals, and soup kitchens in Constantinople, Jerusalem, and Mecca. She died in 1558 and was interred in a mausoleum adjacent to Suleiman's at the Süleymaniye Mosque complex, leaving a complex and enduring legacy as one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history.

2. Early Life and Origin

Hürrem Sultan's early life began in Ruthenia, a region then part of the Polish Crown, specifically in the town of Rohatyn, located 42 mile (68 km) southeast of Lviv (formerly Lwów), a major city in the Ruthenian Voivodeship. Born into a Ruthenian Orthodox family, her native language was the precursor to modern Ukrainian. While her birth name is widely believed to be either Aleksandra or Anastazja Lisowska, sources from the late 16th and early 17th centuries, including the Polish poet Samuel Twardowski, suggest her father was an Orthodox priest named Hawrylo Lisovski, and her mother was Leksandra.

2.1. Name and Etymology

Within the Ottoman Empire, she was primarily known as Haseki Hürrem Sultan or Hürrem Haseki Sultan. The name `خرمHürremPersian`, derived from Persian, means "the joyful one" or "the cheerful one". Some interpretations also link it to the Arabic word `كريمةKarimaArabic`, meaning "noble".

In Europe, she became widely known as Roxelana, a nickname that was not her birth name. This name originates from `RoksolanesRoksolanesLatin`, a generic term used by Ottomans to describe girls from Podolia and Galicia who were captured during slave raids. Thus, "Roxelana" literally translates to "Ruthenian woman" or "the Ruthenian one," referring to her alleged Ruthenian origins. European variations of this name included Roxolena, Roxolana, Roxelane, Rossa, and Ružica.

2.2. Enslavement and Journey to Constantinople

Hürrem's life took a dramatic turn when she was captured by Crimean Tatars during one of their slave raids into Eastern Europe. This occurred sometime between 1512 and 1520, during the reign of Selim I, Suleiman's father. She was likely first transported to Kaffa (modern-day Feodosiya) in Crimea, a major hub of the Ottoman slave trade, before being taken to Constantinople, the Ottoman capital.

Upon her arrival in Constantinople, Hürrem entered the Ottoman Imperial Harem. Accounts vary regarding who introduced her to Sultan Suleiman. One version suggests that Hafsa Sultan, Suleiman's mother, selected Hürrem as a gift for her son. Another claims that it was Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha, Suleiman's confidant and future Grand Vizier, who brought her into the harem. A third account from Shaykh Qutb al-Din al-Nahrawali, a Meccan religious figure who visited Constantinople in 1558, noted that Hürrem had been a servant in the household of Hançerli Hanzade Fatma Zeynep Sultan, a daughter of Şehzade Mahmud (one of Sultan Bayezid II's sons), who then gifted her to Suleiman when he ascended to the throne. Regardless of the exact circumstances, Hürrem began her life in the Ottoman court as a slave, a precarious status from which she would remarkably rise.

3. Rise within the Harem

Hürrem Sultan's entry into the Ottoman Imperial Harem marked the beginning of her extraordinary ascent, culminating in her becoming the favored consort of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

3.1. Entry into the Harem and Gaining Favor

Hürrem likely entered the harem around the age of sixteen. While the precise year of her entry is unknown, it is believed she became Suleiman's concubine around 1520, the year he became sultan, as their first child was born in 1521. Her intelligence, pleasant personality, and striking good looks, particularly her red hair, quickly drew the Sultan's attention. She also shared Suleiman's love for poetry, which further endeared her to him.

Hürrem's rapid rise from a harem slave to Suleiman's most prominent consort, surpassing Gülbahar Mahidevran Hatun, the mother of Suleiman's eldest son, generated considerable jealousy and disapproval within the harem and among the general populace. Her unprecedented status challenged the existing harem dynamics, which traditionally limited a concubine's influence and the number of sons she could bear.

3.2. Marriage and the Haseki Sultan Title

Breaking a centuries-old Ottoman tradition that sultans only married foreign freeborn noblewomen, Suleiman married Hürrem in a magnificent formal ceremony around 1533 or 1534. This act was astonishing to observers both within the palace and throughout the city, as it elevated a former slave to the status of the Sultan's lawful spouse. Before the marriage, Suleiman legally freed Hürrem from slavery, a necessary step for her to become his wife.

Following their marriage, Hürrem became the first imperial consort to receive the newly created title of "Haseki Sultan". This title, which added "Sultan" to a woman's name or title to indicate her dynastic status, reflected the immense power and elevated status of imperial consorts in the Ottoman court, placing them even higher than Ottoman princesses. Hürrem's daily salary of 2,000 akçe made her one of the highest-paid women in the empire. Her marriage to Suleiman not only broke old customs but also initiated a new tradition for future Ottoman sultans, allowing their consorts to marry formally and exert significant influence, particularly in matters of succession. The marriage also led to rumors that the Sultan had limited his autonomy and was under his wife's domination.

4. Relationship with Suleiman the Magnificent

Hürrem's relationship with Sultan Suleiman was characterized by a deep personal connection and a significant departure from established Ottoman traditions regarding imperial consorts.

4.1. Personal Life and Family

Hürrem and Suleiman shared a remarkably close and monogamous relationship. Their personal bond is evident in the numerous love letters they exchanged when Suleiman was away on campaigns. Hürrem's letters expressed intense longing and devotion, while Suleiman, writing under his pen name Muhibbi, composed heartfelt poems for her, referring to her as "Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight" and "My one and only love."

Hürrem bore Suleiman six children: five sons and one daughter. Their children were:

- Şehzade Mehmed (1521-1543): Hürrem's firstborn, he became the sanjak-bey of Manisa and was considered a presumptive heir until his death from smallpox.

- Mihrimah Sultan (1522-1578): Hürrem's only daughter, she later married Rüstem Pasha, who became the Grand Vizier.

- Selim II (1524-1574): He succeeded Suleiman as Sultan on September 7, 1566.

- Şehzade Abdullah (c. 1525-c. 1528): Died at a young age.

- Şehzade Bayezid (1527-1561): Governor of various provinces, he later rebelled against his father and was executed.

- Şehzade Cihangir (1531-1553): Born with kyphosis (also described as rickets) and in poor health, he was deemed unfit for succession and died shortly after his half-brother Mustafa's execution, possibly from grief.

Hürrem's ability to bear multiple sons to the Sultan was a stark violation of the traditional imperial harem principle of "one concubine mother - one son." This old custom was designed to prevent excessive maternal influence over the Sultan and to minimize feuds among half-brothers vying for the throne. Hürrem not only bore more than one son but was also the mother of all of Suleiman's children born after her entry into the harem at the beginning of his reign, effectively securing the future of the Ottoman dynasty through her lineage.

4.2. Influence on Court Life

Hürrem's prolonged presence in the Sultan's court, even after her sons came of age, marked another significant departure from Ottoman imperial family tradition. The custom of Sancak Beyliği dictated that a sultan's consort would accompany her son to a faraway province once he reached maturity (around 16 or 17) to govern, and she would not return to Constantinople unless her son ascended to the throne. Hürrem defied this age-old practice, remaining in the harem in Constantinople even after her sons were sent to govern remote provinces.

Furthermore, Hürrem moved permanently from the Old Palace (Eski Saray) to the Topkapı Palace, where the government affairs were conducted. This move, whether prompted by a fire that destroyed the old harem or as a direct consequence of her marriage to Suleiman, was a revolutionary act. Mehmed the Conqueror had previously issued a decree forbidding women from residing in the same building as the government. After Hürrem took residence there, Topkapı became known as the New Palace (saray-ı jedid), symbolizing her consolidated influence within the imperial household. She also became Suleiman's most trusted source of news, informing him about matters such as the plague in the capital.

5. Political Influence and State Affairs

Hürrem Sultan's active engagement in Ottoman politics and state affairs was a defining aspect of her life, establishing her as a formidable figure and initiating a new era of female influence.

5.1. Advisory Role and Diplomacy

Hürrem was one of the most educated women of her time and played a crucial role in the political life of the Ottoman Empire. Initially, Suleiman relied on correspondence with his mother rather than Hürrem due to her limited command of the language. However, as her linguistic skills improved, she corresponded regularly with her husband when he was away on campaigns, conveying greetings from statesmen and the Sheikh-ul-Islam of Istanbul, and discussing pressing issues in the capital. She took a keen interest in the problems faced by statesmen and offered her insights and ideas to Suleiman in her letters.

Her influence extended to foreign policy and international politics. She freely communicated with European ambassadors, corresponded with the rulers of Venice and Persia, and stood by Suleiman at receptions and banquets. She even imprinted her own seal on documents and observed council meetings through a wire mesh window, a revolutionary act for a consort. For the first time in Ottoman history, Hürrem began using the title of Shah, meaning queen, after she became a legitimate wife, with her signature often appearing as Hürrem Shah. This expression is seen in the records of the Haseki Hospital and in the inscription of the soup kitchen and hospital in Jerusalem, affirming her elevated status.

Two of her letters to Sigismund II Augustus, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (reigned 1548-1572), have survived, highlighting her direct engagement in diplomacy. In her first letter, she expressed joy and congratulations on his accession to the Polish throne, urging him to trust her envoy. Her second letter, in response to his, conveyed her happiness at his good health and his assurances of friendship towards Suleiman. She quoted Suleiman as saying, "with the old king we were like brothers, and if it pleases the All-Merciful God, with this king we will be as father and son." This suggests a special bond between the two states during her lifetime, with the Ottoman Empire generally maintaining peaceful relations with Poland. Hürrem also sent gifts to Sigismund II, including linen shirts, pants, belts, and handkerchiefs. Notably, Hürrem was the first and only female sultan in the Ottoman Empire to exchange letters personally with a king, setting a precedent that even her successors, Nurbanu Sultan and Safiye Sultan, only replicated with queens.

5.2. The Sultanate of Women

Hürrem's revolutionary actions, such as her marriage to the Sultan, her continued presence in the capital, and her direct involvement in state affairs, ushered in an era known as the "Sultanate of Women" (Kadınlar SaltanatıTurkish). This period, which lasted for over a century, saw imperial consorts, many of whom were former slaves, gain unprecedented political influence within the Ottoman court. Hürrem's power as Haseki Sultan became comparable to that of the valide sultan (Sultan's mother), traditionally the most powerful woman in the Imperial Harem. By legally marrying the Sultan, Hürrem uniquely combined the roles and powers of both Haseki Sultan and Valide Sultan, making her a pivotal figure in this transformation of Ottoman governance. Her significant influence over Suleiman was so widely recognized that rumors circulated within the court that the Sultan had been bewitched.

6. Rivalries and Controversies

Hürrem Sultan's rise to power was not without significant conflicts and controversies, particularly her intense rivalries within the harem and her alleged involvement in political intrigues that led to the downfall of prominent figures.

6.1. Rivalry with Mahidevran

An intense rivalry existed between Hürrem and Mahidevran, the mother of Suleiman's eldest son, Şehzade Mustafa. Traditionally, the mother of the eldest son held a privileged position as the potential future Valide Sultan. However, Hürrem's rapid ascent challenged Mahidevran's status. The conflict between the two women was so bitter that, according to one report by Venetian ambassador Bernardo Navagero, a physical altercation occurred where Mahidevran beat Hürrem. This incident reportedly angered Suleiman, contributing to Mahidevran's eventual loss of favor and her subsequent departure from the palace. After the death of Suleiman's mother, Hafsa Sultan, in 1534, Hürrem's influence in the palace further increased, and she assumed control over the management of the harem.

6.2. Succession Disputes and Political Intrigue

Hürrem's ambition to secure the throne for one of her own sons led to her alleged involvement in the succession struggles among Suleiman's children. The Ottoman Empire, until the reign of Ahmed I, lacked a formal system for nominating a successor, often resulting in fierce competition and the elimination of rival princes to prevent civil unrest. Hürrem and Mahidevran had given birth to six şehzades (Ottoman princes) for Suleiman: Mustafa, Mehmed, Selim, Abdullah, Bayezid, and Cihangir. Mustafa, Mahidevran's son, was the eldest and thus the primary heir. To avoid the traditional practice of kardeş katliamı (fraternal massacring) that would likely befall her sons if Mustafa ascended, Hürrem is often accused of using her influence to eliminate those who supported Mustafa's claim.

Her alliance with her daughter, Mihrimah Sultan, and her son-in-law, Rüstem Pasha, who became Grand Vizier, is believed to have been instrumental in these machinations. Scholars have speculated that this alliance helped secure the throne for one of Hürrem's sons.

6.3. Allegations Regarding Executions

Hürrem is widely alleged to have influenced the downfall and execution of several prominent figures, most notably Grand Vizier Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha and Şehzade Mustafa.

Ibrahim Pasha, a skilled commander and Suleiman's Grand Vizier since 1523, fell from grace after an imprudence during a campaign against the Persian Safavid empire, where he awarded himself a title that included the word "Sultan." Conflicts with his former mentor, İskender Çelebi, also contributed to his decline. These incidents culminated in his execution in 1536 by Suleiman's order. While direct evidence is scarce, it is widely believed that Hürrem's influence contributed to Suleiman's decision. After three other grand viziers in eight years, Suleiman appointed Hürrem's son-in-law, Rüstem Pasha, as Grand Vizier, further solidifying her faction's power.

Years later, towards the end of Suleiman's reign, the rivalry between his sons intensified. Şehzade Mustafa, who was highly popular with the army, particularly the Janissaries, was accused of causing unrest. During the campaign against Safavid Persia in 1553, Suleiman, fearing rebellion, ordered Mustafa's execution. His guilt for treason remains unproven. Rumors persist that Hürrem Sultan conspired against Mustafa with the help of Mihrimah and Rüstem Pasha. It is alleged that Rüstem Pasha forged Mustafa's seal to send a letter to Shah Tahmasb I of Iran, and then presented the Shah's response to Suleiman, framing Mustafa as a traitor secretly contacting a foreign power. After Mustafa's death, Mahidevran lost her status and moved to Bursa, though she was later granted a generous salary by Hürrem's son, Selim II, after Hürrem's death. Hürrem's youngest child, Şehzade Cihangir, is said to have died of grief a few months after his half-brother's murder. Another figure whose execution Hürrem is sometimes linked to is Kara Ahmed Pasha, who briefly served as Grand Vizier after Rüstem Pasha's first dismissal.

It is important to note that while stories about Hürrem's role in these executions are popular, none are based on first-hand sources. Contemporary Ottoman historians, European diplomats, and travelers largely relied on hearsay, rumors circulating in Constantinople, or the testimony of servants and courtiers, as they were not permitted into the inner circle of the imperial harem. Even the reports of Venetian ambassadors, considered the most extensive Western sources, often contained their own interpretations of harem gossip. Therefore, depictions of Hürrem as a cunning, manipulative, and stony-hearted woman who would eliminate anyone in her path are largely speculative.

7. Charitable Works and Patronage

Beyond her political influence, Hürrem Sultan was renowned for her extensive philanthropic activities and patronage of public works, demonstrating a deep commitment to social welfare. She modeled some of her charitable foundations after figures like Zubaida, the consort of Caliph Harun al-Rashid.

7.1. Architectural Projects

Hürrem commissioned numerous significant public works from Mecca to Jerusalem. Among her earliest and most notable foundations in Constantinople was the Haseki Sultan Complex, designed by Mimar Sinan in his new role as chief imperial architect. This complex included a mosque, two Quranic schools (madrasas), a fountain, and a women's hospital near the women's slave market (Avret Pazary). The mosque was completed in 1538-39, the madrasa in 1539-40, and the soup kitchen in 1540-41, with the hospital following in 1550-51. Its size, being the third largest building in the capital after the Fatih Mosque and Süleymaniye Mosque, underscored Hürrem's high status.

She also commissioned mosque complexes in Adrianopole and Ankara. In 1556, she commissioned the Hürrem Sultan Bathhouse (Haseki Hürrem Sultan HamamıTurkish), also designed by Mimar Sinan, to serve the community of worshippers at the nearby Hagia Sophia. This 246 ft (75 m)-long structure featured two separate, symmetrical sections for men and women, a novel design in Turkish bath architecture. Its income was dedicated to financially supporting the Hagia Sophia.

In Jerusalem, Hürrem established the Haseki Sultan Imaret in 1552, a public soup kitchen designed to feed the poor. This facility was said to have provided two meals a day to at least 500 people. The endowment for this imaret included extensive assets, such as land in Palestine and Tripoli, as well as shops, public bathhouses, soap factories, and flourmills. The endowment deed itself listed 195 toponyms and 32 estates, primarily along the road between Jaffa and Jerusalem. The Haseki Sultan Imaret not only fulfilled religious obligations of charity but also reinforced social order and projected an image of Ottoman power and generosity. She also established a public soup kitchen in Mecca.

7.2. Social Welfare and Philanthropy

Hürrem's philanthropic endeavors extended beyond grand architectural projects to direct social welfare initiatives. Her foundation charters from 1540 and 1551 documented donations for the long-term maintenance of these public works, as well as for existing dervish convents in various Istanbul districts. These charters, signed by a judge (Qādī) and witnesses, ensured the sustainability of her charitable contributions. She also employed a Kira, a Jewish woman who served as her secretary and intermediary for various affairs, including her charitable works.

8. Personality and Contemporary Views

Hürrem Sultan's personality was a subject of fascination and contrasting interpretations among her contemporaries and later historians. She was widely described as a woman of striking beauty, often noted for her distinctive red hair. Beyond her physical appearance, she was recognized for her intelligence, charm, and a generally pleasant disposition. Her deep love for poetry is often cited as a significant factor in her strong favor with Sultan Suleiman, who himself was a great admirer of the art.

While her extensive philanthropy, which included building numerous mosques, madrasahs, hammams, and resting places for pilgrims, demonstrated a profound generosity towards the poor, historical accounts also present a more critical view. Some believed Hürrem to be cunning, manipulative, and even stony-hearted, willing to eliminate anyone who stood in her way to achieve her goals. However, her charitable works stand in stark contrast to this negative perception, highlighting her genuine concern for the welfare of the populace.

Prominent Ukrainian writer Pavlo Zahrebelny offered a particularly positive portrayal, describing Hürrem as "an intelligent, kind, understanding, openhearted, candid, talented, generous, emotional and grateful woman who cares about the soul rather than the body; who is not carried away with ordinary glimmers such as money, prone to science and art; in short, a perfect woman." Venetian ambassadors also provided mixed reports; while some noted her pleasant and cheerful nature, others described her as "cunning." These diverse perspectives underscore the complex and multifaceted nature of Hürrem Sultan's personality as perceived by those around her and by later generations.

9. Death and Burial

Hürrem Sultan died on April 15, 1558, at the age of approximately 54, after a period of poor health due to an unknown illness. During her final years, her health significantly deteriorated. It is said that Sultan Suleiman, deeply devoted to her, ordered all musical instruments in the palace to be burned to ensure his wife's peace during her illness. He remained by her bedside until her last day. The farewell dedications written by the Sultan to Hürrem after her death, which have been preserved, attest to the profound love and grief he felt for her.

She was buried in a domed mausoleum (türbe) located within the courtyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque complex in Fatih, Istanbul. Her mausoleum is exquisitely decorated with Iznik tiles depicting the garden of paradise, a design perhaps chosen to symbolize her joyful and smiling nature. This tomb is situated adjacent to Suleiman's own mausoleum, a more somber domed structure, signifying their enduring bond even in death. The architectural design of their octagonal, domed mausoleums, with their complex arrangements, notably differed from the traditional single-domed, simple polygonal structures of the time.

10. Legacy and Cultural Impact

Hürrem Sultan's lasting legacy is profound, influencing Ottoman history and inspiring countless artistic and literary works across various cultures and centuries.

10.1. Depictions in Art and Literature

Hürrem Sultan has been widely represented in art, literature, and popular culture. In 1561, just three years after her death, the French author Gabriel Bounin wrote a tragedy titled La Soltane, which is notable as the first time Ottomans were introduced on stage in France.

She has inspired numerous paintings, including an 18th-century portrait kept at Topkapı Palace and a 17th-century portrait in the British Royal Collection. The Venetian painter Titian is reputed to have painted Hürrem in 1550, though he never visited Constantinople, relying on imagination or sketches. His portrait of Hürrem bears a resemblance to his painting of her daughter, Mihrimah Sultan. Other European artists like Melchior Lorck and Sebald Beham also contributed to her visual representation, often emphasizing her beauty and wealth with elaborate headwear, despite these being largely imagined depictions.

In music, she inspired Joseph Haydn's Symphony No. 63, subtitled "La Roxelane." Her story has also been adapted into operas, ballets, and plays. Numerous novels have been written about her, primarily in Russian and Ukrainian, but also in English, French, German, Polish, Serbo-Croatian, and Turkish. Notable examples include P.J. Parker's Roxelana and Suleyman, Barbara Chase Riboud's Valide, and Pavlo Zahrebelny's Ukrainian novel. In early modern Spain, she appears or is alluded to in works by Francisco de Quevedo and in several plays by Lope de Vega, such as The Holy League, where Titian displays his painting of Sultana Rossa or Roxelana.

In popular culture, Hürrem has been portrayed in various television series and films. She was played by Turkish actress and singer Gülben Ergen in the 2003 TV miniseries Hürrem Sultan. In the highly popular 2011-2014 Turkish TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl (Muhteşem YüzyılTurkish, The Magnificent Century), she was portrayed by Turkish-German actress Meryem Uzerli for the first three seasons and by Turkish actress Vahide Perçin for the final season. Australian actress Megan Gale also portrayed her in the 2022 movie Three Thousand Years of Longing. In 2013, Croatian singer Severina released a song titled "Hurem" following the TV series' success in Croatia.

10.2. Historical Re-evaluation

Hürrem Sultan's life and actions have been subject to ongoing historical re-evaluation, offering a nuanced perspective on her complex legacy. Her rise from enslavement to the pinnacle of Ottoman power is often highlighted as a testament to her extraordinary intelligence, ambition, and political acumen. She is recognized for her philanthropic endeavors, which greatly benefited the populace and left a lasting architectural mark on the empire.

However, her legacy is also intertwined with controversies, particularly the allegations surrounding her involvement in the executions of Şehzade Mustafa and Ibrahim Pasha. While these stories are deeply embedded in popular narratives, historical scholars emphasize the lack of definitive first-hand sources, suggesting that many accounts are based on rumors and speculation from a period when direct access to the imperial harem was restricted. This critical perspective encourages a balanced understanding, acknowledging her influence and the political realities of the time without definitively attributing all intrigues to her.

In 2007, Muslims in Mariupol, Ukraine, opened a mosque to honor Roxelana, reflecting her continued significance in her homeland. In 2019, a reference to Hürrem's "Russian origin" was removed from a visitor panel near her tomb at the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul at the request of the Ukrainian embassy in Turkey, underscoring the contemporary efforts to accurately represent her national identity. Hürrem's life continues to be a subject of fascination and debate, symbolizing both the opportunities and the ruthless power struggles within the Ottoman court. After Suleiman's death, his successor Selim II, often called "Sarı Selim" (Drunkard Selim), largely left state affairs to his officials and spent his days indulging in wine and women at the "Bab-us-Saade" (Gate of Felicity) palace. This marked a shift where Ottoman state administration became increasingly dominated by officials rather than the Sultan.

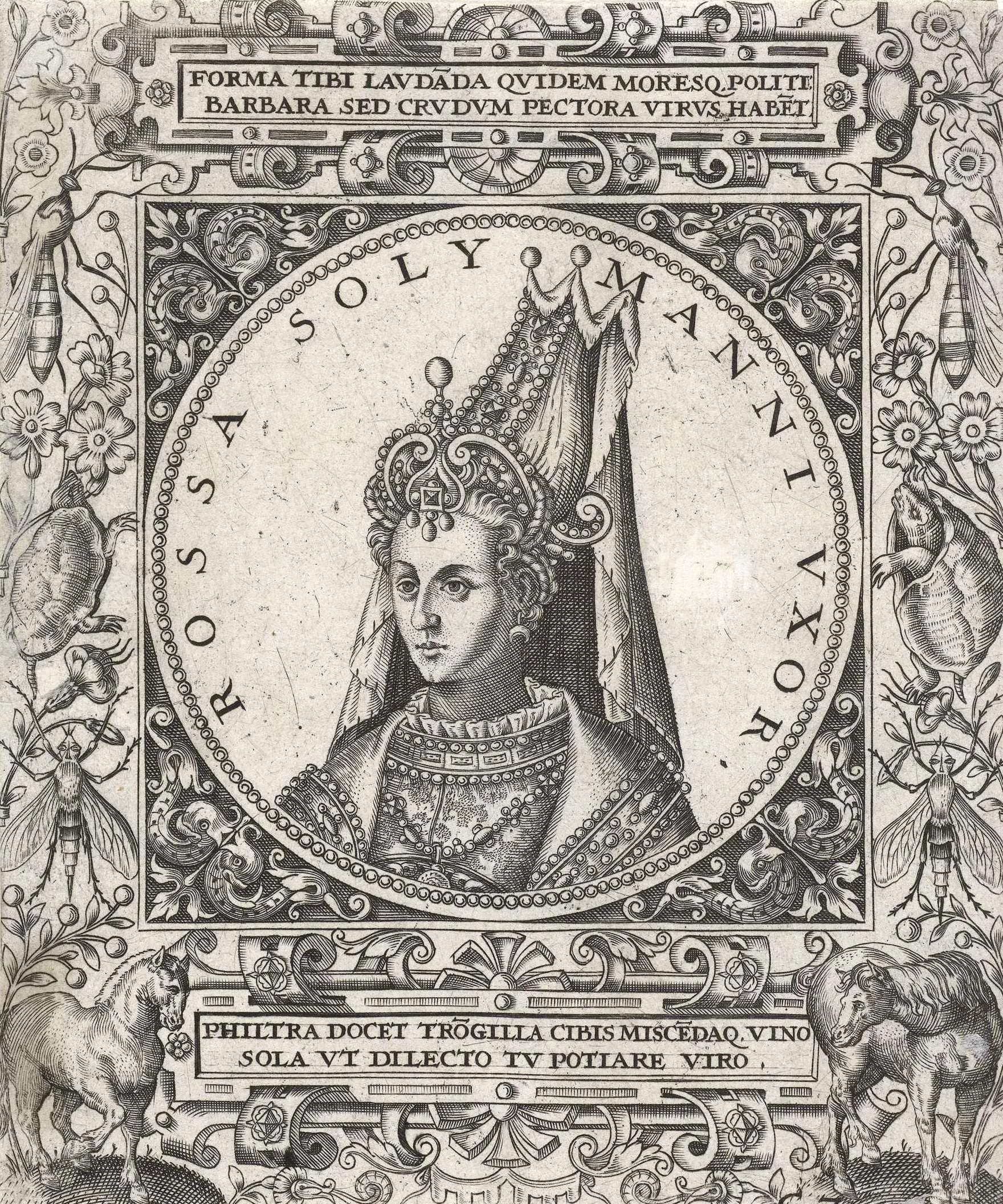

11. Visual Representations

Despite the fact that male European artists were denied direct access to Hürrem within the confines of the harem, a significant number of Renaissance paintings depicting the famous sultana exist. Scholars generally agree that these European artists largely created an imagined visual identity for Ottoman women, relying on secondhand accounts, sketches, or their own artistic interpretations rather than direct observation.

Images of Hürrem often emphasized her beauty and wealth, and she is almost invariably depicted with elaborate headwear. The Venetian painter Titian is widely credited with painting Hürrem in 1550. Although he never visited Constantinople, he either imagined her appearance or worked from a preliminary sketch. In a letter to Philip II of Spain, Titian claimed to have sent him a copy of this "Queen of Persia" in 1552. The Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida, acquired an original or copy around 1930. Notably, Titian's painting of Hürrem bears a strong resemblance to his portrait of her daughter, Mihrimah Sultan.

Other influential artists in creating visual representations of Hürrem included Melchior Lorck and Sebald Beham. These portraits, though often speculative, played a crucial role in shaping her image and identity in the Western world, contributing to her mystique and enduring fame.

Her visual legacy also includes various depictions from the 16th century.

Another notable 16th-century work is an oil on wood painting.