1. Overview

Robert Broom was a prominent Scottish-South African medical doctor and palaeontologist who made groundbreaking contributions to the fields of therapsid research and palaeoanthropology. Born in Paisley, Scotland, in 1866, Broom initially pursued a career in medicine, specializing in obstetrics at the University of Glasgow. His early travels and medical practice in Australia and later in South Africa laid the foundation for his deep interest in mammalian evolution and vertebrate palaeontology.

Broom's career in South Africa began with an academic post at Victoria College, where his fervent advocacy for evolutionary theory led to his eventual departure. He then established a medical practice in the Karoo region, a rich source of therapsid fossils, allowing him to continue his palaeontological studies. His significant work on therapsids, ancient mammal-like reptiles, earned him recognition as a leading figure in the field. Following Raymond Dart's discovery of the Taung Child, Broom shifted his focus to early human ancestors, dedicating the latter part of his life to palaeoanthropology. His most notable discoveries include the nearly complete skull of an Australopithecus africanus, famously nicknamed Mrs. Ples, and the definition of the robust hominin genus Paranthropus with the discovery of Paranthropus robustus. These finds provided crucial evidence for understanding hominin evolution and the development of bipedalism.

Beyond his scientific endeavors, Broom held unconventional philosophical and spiritual views, critiquing Darwinism and materialism while advocating for a concept of "spiritual evolution" guided by non-material forces. His later anthropological research on the Khoisan peoples, however, is viewed critically today due to his methods of collecting human remains and his use of now-discredited typological racial classifications, reflecting the problematic scientific practices of the early 20th century. Despite these controversies, Broom received numerous accolades, including fellowships from the Royal Society and prestigious scientific medals, solidifying his legacy as a pivotal figure in the study of human origins. He passed away in 1951, leaving behind an extensive body of published work that continues to influence the understanding of our evolutionary past.

2. Early Life and Education

Robert Broom was born on November 30, 1866, at 66 Back Sneddon Street in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland. He came from a modest background; his father, John Broom, was a designer of calico prints and Paisley shawls, and his mother was Agnes Hunter Shearer.

Broom pursued his higher education at the University of Glasgow, where he specialized in obstetrics during his medical studies. He graduated in 1895, earning his medical degree. In 1905, he received his DSc from the same university. During his time as a student, he traveled extensively around the world as an assistant to a professor, which broadened his horizons. In 1893, he married Mary Baird Baillie, his childhood sweetheart.

After graduating, Broom traveled to Australia in 1892, where he supported himself by practicing medicine. His observations of Australia's unique wildlife sparked an early interest in the origins of mammals.

3. Career in South Africa

Broom settled in South Africa in 1897, just before the outbreak of the South African War. His career in the country saw him transition from medical practice to academia and, eventually, to dedicated palaeontological research, often facing challenges due to his scientific views.

3.1. Medical Activities

Upon his arrival in South Africa, Broom established a medical practice, initially in the Karoo region. This area was particularly significant as it was rich in therapsid fossils, which allowed him to pursue his growing interest in palaeontology alongside his medical duties. He supported himself and his family through his medical work, which also involved engaging with local communities and providing patient care.

3.2. Academic Activities and Education

From 1903 to 1910, Broom held a professorship in Zoology and Geology at Victoria College in Stellenbosch, which later became Stellenbosch University. During his tenure, he was a strong advocate for evolutionary theory, a stance that was controversial at the time. His promotion of evolutionary beliefs eventually led to him being forced out of his academic position.

Despite this setback, Broom's dedication to science remained unwavering. He continued his studies on therapsid fossils and mammalian anatomy, which led to his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1920. In 1934, after Raymond Dart appealed to Jan Smuts regarding Broom's financial difficulties and his potential contributions, Smuts intervened, securing Broom a position as an Assistant in Palaeontology with the staff of the Transvaal Museum in Pretoria. He also served as the keeper of vertebrate palaeontology at the South African Museum in Cape Town.

4. Palaeontological and Palaeoanthropological Contributions

Broom's scientific career was marked by extensive research in both palaeontology, particularly on therapsids, and a pivotal shift to palaeoanthropology, which led to some of the most significant discoveries in the study of human origins.

4.1. Therapsid Research

Broom initially gained prominence for his extensive work on therapsids, a group of mammal-like reptiles that are crucial to understanding the evolutionary transition to mammals. He is recognized as one of the foremost palaeontologists to study the rich fossil deposits of the Karoo region in South Africa. Throughout his lifetime, Broom described a remarkable 369 therapsid holotypes, which he initially attributed to 168 new genera. His contributions significantly advanced the understanding of mammalian origins. However, Broom also developed a reputation as a "splitter" in taxonomy, meaning he tended to create many new species and genera based on minor differences. As a result, as of 2003, only approximately 57% of the holotypes he described are still considered taxonomically valid. His seminal work, The mammal-like reptiles of South Africa and the origin of mammals, published in 1932, summarized much of his research in this area.

4.2. Transition to Palaeoanthropology

Broom's interest in palaeoanthropology was profoundly sparked by Raymond Dart's announcement in 1925 of the discovery of the Taung Child, an infant Australopithecus africanus. Broom was highly impressed by Dart's findings and developed a strong interest in the Australopithecus genus. Despite being 70 years old, Broom began his own research into Australopithecines in 1936. His move to the Transvaal Museum in 1934, after retiring from medical practice, allowed him to join a team dedicated to the excavation of early hominin fossils, marking a significant shift in his research focus.

4.3. Major Fossil Discoveries

Working primarily in the dolomite caves northwest of Johannesburg, particularly at sites like Sterkfontein, Kromdraai, and Swartkrans (now part of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site), Broom and his colleagues, notably John T. Robinson, made a series of spectacular discoveries of hominin and hominid fossils. Broom employed a unique method to locate fossil-rich areas, paying local boys one shilling for each fossil tooth they brought him, and then using their information to find the discovery sites.

4.3.1. Mrs Ples (Australopithecus africanus)

One of Broom's most famous discoveries occurred in 1947 at the Sterkfontein site. This was the finding of a nearly complete female skull of an Australopithecus africanus, popularly nicknamed "Mrs. Ples". Although initially named Plesianthropus transvaalensis by Broom and Robinson, it was later reclassified as an adult Australopithecus africanus. The discovery of Mrs. Ples, along with a partial skeleton that included ribs and part of a femur found in the same year, provided crucial evidence suggesting that australopithecines walked upright, a key development in hominin evolution.

4.3.2. Paranthropus robustus

In 1937, Broom made another pivotal discovery at Kromdraai by defining a new robust hominin genus, Paranthropus, with the finding of Paranthropus robustus. This discovery was highly significant as it helped to corroborate Dart's earlier claims regarding the Taung Child and demonstrated the diversity among early hominins, distinguishing the more robust, large-jawed Paranthropus from the more gracile Australopithecus.

4.3.3. Other Early Hominin Fossils

Beyond Mrs. Ples and Paranthropus robustus, Broom and his team unearthed other notable hominin fossils. In 1948, at Swartkrans, they discovered fossils that were distinct from the Australopithecus genus, which were later identified as belonging to Homo erectus. These various finds, including those indicating bipedalism in australopithecines, significantly expanded the fossil record of early human ancestors.

4.4. Contributions to Early Hominin Evolution Research

Broom's extensive fossil discoveries, particularly those from the South African cave sites, provided crucial evidence that profoundly shaped the understanding of hominin evolution. His work, alongside that of Raymond Dart, helped to solidify the scientific community's acceptance of Australopithecus as a genuine early human ancestor. The fossils he unearthed offered insights into the development of bipedalism, the diversification of early human lineages, and the complex evolutionary pathways that led to modern humans. His volume, The South Africa Fossil Ape-Men, The Australopithecinae, published in 1946, in which he proposed the Australopithecinae subfamily, was a landmark publication that synthesized his findings and was recognized with the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences. The remainder of Broom's career was dedicated to the exploration of these sites and the interpretation of the many early hominin remains discovered there, continually contributing to the field until his death.

5. Philosophical and Spiritual Views

Robert Broom held a unique and often unconventional set of beliefs that extended beyond his scientific work. He was a nonconformist and showed a deep interest in the paranormal and spiritualism. He was a vocal critic of both Darwinism and materialism, arguing against purely mechanistic explanations for life's complexity and evolution.

5.1. Spiritual Evolution

Broom was a firm believer in what he termed "spiritual evolution." In his 1933 book, The Coming of Man: Was it Accident or Design?, he posited that "spiritual agencies" had guided the evolutionary process. He argued that the intricate complexity of animals and plants could not have arisen by mere chance, suggesting an underlying design. According to Broom, there were at least two distinct kinds of spiritual forces, which he believed psychics were capable of perceiving. His conviction in these guiding spiritual forces was so strong that, after discovering the skull of Mrs. Ples, he reportedly told a colleague that spirits had explicitly guided him to his discoveries.

5.2. Views on Evolution

Broom's perspective on evolution diverged significantly from the prevailing materialistic views of his time. He saw evolution as a purposeful process, ultimately leading to the emergence of humanity. He famously stated, "Much of evolution looks as if it had been planned to result in man, and in other animals and plants to make the world a suitable place for him to dwell in." This teleological view of evolution, where humanity is the ultimate goal, underpinned his criticisms of purely materialistic explanations for the development of life, which he felt failed to account for the apparent design and direction he observed in the natural world.

6. Research on the Khoisan Peoples

Robert Broom's anthropological research on the Khoisan peoples represents a controversial aspect of his career, reflecting the problematic scientific and social attitudes prevalent in the early 20th century. Broom developed a significant interest in the Khoisan, which unfortunately led him to engage in methods of collecting human remains that are now widely condemned.

Starting in 1897, shortly after his move to South Africa, Broom began collecting modern human remains. In that year, following a drought around Port Nolloth, he collected the remains of three elderly "Hottentot" individuals who had recently died. Broom himself described his methods, stating that he "cut their heads off and boiled them in paraffin tins on the kitchen stove." These skulls, along with a 7-month-old fetus from which Broom had separately preserved the brain, were later sent to the medical school of the University of Edinburgh.

Broom also obtained remains of deceased prisoners, expressing a disregard for regulations in his pursuit of specimens: "If a prisoner dies and you want his skeleton, probably two or three regulations stand in the way, but the enthusiast does not worry about such regulations." He even admitted to burying several corpses in his garden, allowing them to decay before retrieving their bones. Among these were the remains of two men imprisoned in Douglas jail: Andreas Links, an 18-year-old !Ora man (catalogued as MMK 264), as well an unnamed 18-year-old "bushman" from Langeberg (catalogued as MMK 283), who was photographed while alive at Broom's request, despite it being against policy. The skeletons of both men were added to the collections of the McGregor Museum in 1921.

In his 1907 writings, Broom described the Khoisan peoples as a "degenerate" and "degraded race." He speculated that they were descendants of "the race which built the Pyramids" and "Mongoloids," but had "degenerated" due to South Africa's hot climate. In his later works, he further divided the Khoisan into three distinct "races"-the Bushmen, Hottentot, and Korana-based on supposed typological differences. The skeleton of Andreas Links, for instance, was designated as the type specimen for the Korana race. However, other contemporary anthropologists questioned this classification scheme, particularly the existence of a distinct Korana race. Broom himself later conceded that he had "invented the Korana." Today, all such typological racial classification schemes are discredited, as they are recognized as being based on vague and arbitrary criteria, leading to rigid and ultimately unscientific categorizations. Anatomist Goran Štrkalj critically noted that "It is obvious that Broom's anthropological work was ... influenced by the racist stereotypes and prejudices of the day."

7. Awards and Recognition

Robert Broom received numerous significant honors and recognitions throughout his career, acknowledging his profound contributions to palaeontology and palaeoanthropology.

7.1. Fellowship

His standing in the international scientific community was recognized through his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1920. He was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE). These fellowships are among the highest distinctions for scientists, reflecting the significant impact and quality of his research.

7.2. Major Scientific Medals

Broom was awarded several prestigious scientific medals for his groundbreaking work:

- The Crunian Medal in 1913.

- The Royal Medal in 1928, awarded by the Royal Society for "the most important contributions to the advancement of Natural Knowledge."

- The Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 1946, specifically for his volume The South Africa Fossil Ape-Men, The Australopithecinae, in which he proposed the Australopithecinae subfamily.

- The Wollaston Medal in 1949, the highest award given by the Geological Society of London, recognizing his exceptional contributions to geology and palaeontology.

8. Publications

Robert Broom was a prolific writer, contributing hundreds of articles to scientific journals and authoring several influential books that shaped the fields of palaeontology and palaeoanthropology.

His most important articles include:

- "Fossil Reptiles of South Africa" in Science in South Africa (1905)

- "Reptiles of Karroo Formation" in Geology of Cape Colony (1909)

- "Development and Morphology of the Marsupial Shoulder Girdle" in Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1899)

- "Comparison of Permian Reptiles of North America with Those of South Africa" in Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (1910)

- "Structure of Skull in Cynodont Reptiles" in Proceedings of the Zoölogical Society (1911)

His major books include:

- The origin of the human skeleton: an introduction to human osteology (1930)

- The mammal-like reptiles of South Africa and the origin of mammals (1932)

- The coming of man: was it accident or design? (1933)

- The South African fossil ape-man: the Australopithecinae (1946)

- Sterkfontein ape-man Plesianthropus (1949)

- Finding the missing link (1950)

9. Personal Life and Personality

Robert Broom's personal life was characterized by his marriage and a distinctive, often eccentric, personality coupled with an unwavering dedication to his scientific pursuits. He married Mary Baird Baillie, his childhood sweetheart, in 1893.

Broom was known for his idiosyncratic habits, such as consistently appearing at fossil excavation sites dressed in a full suit, regardless of the rugged conditions. His colleagues and the public often found him to be a peculiar figure. Despite his eccentricities, his relentless drive and passion for discovery were widely admired. He continued to work tirelessly, making global scientific breakthroughs even past the age of 70, a testament to his enduring commitment to his field.

10. Death

Robert Broom died on April 6, 1951, in Pretoria, South Africa. His dedication to his work continued literally until his final moments. Shortly before his death, he completed a comprehensive monograph on the Australopithecines. Upon finishing this significant work, he reportedly remarked to his nephew, "Now that's finished ... and so am I," encapsulating his lifelong devotion to science.

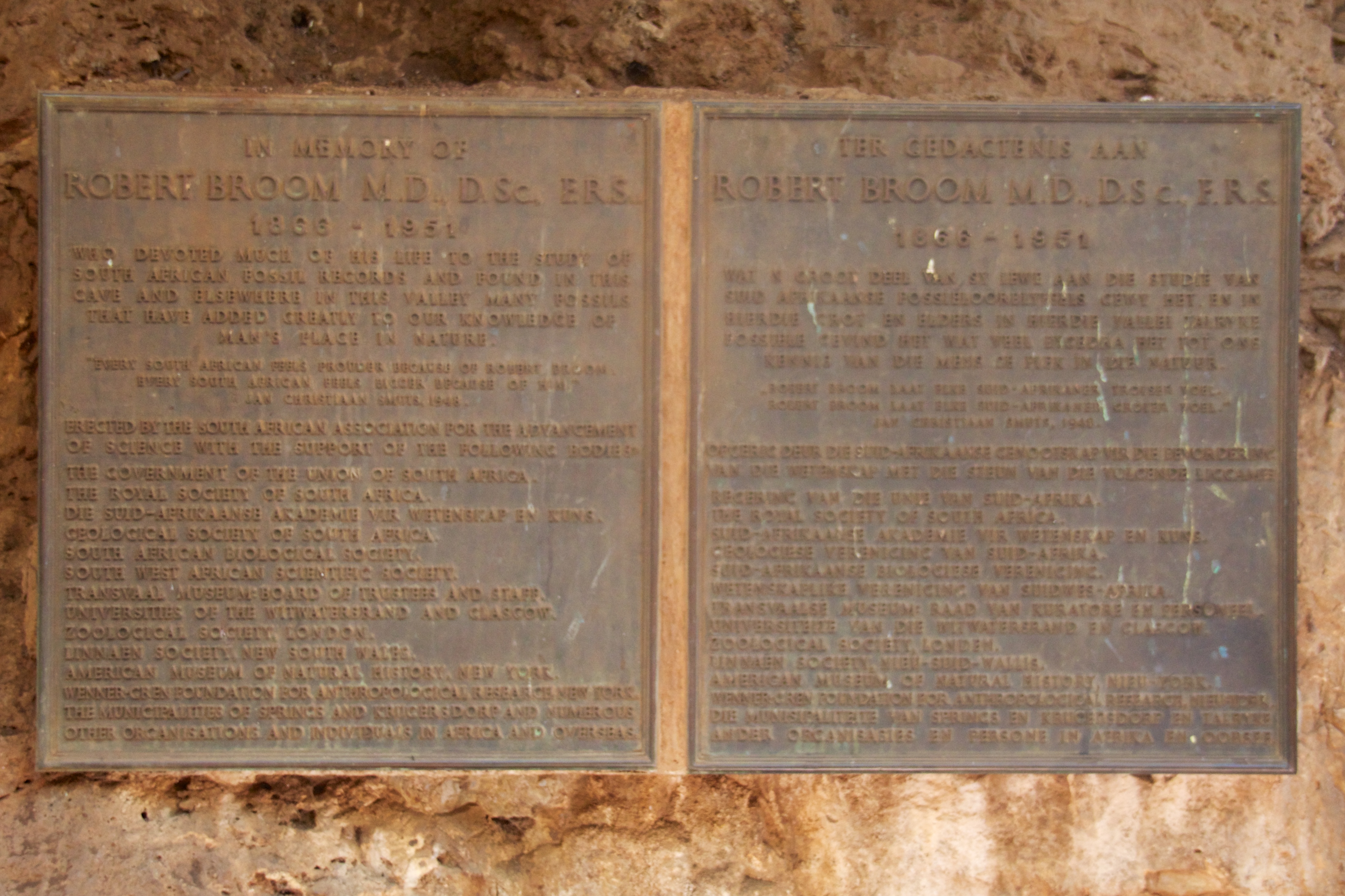

11. Legacy

Robert Broom's legacy is profound and enduring, particularly in the fields of palaeontology and palaeoanthropology. His extensive fossil discoveries, especially those related to early hominins in South Africa, provided critical evidence that significantly advanced the understanding of human evolution. He played a pivotal role in establishing the importance of the South African fossil sites, now recognized as the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site.

His contributions are commemorated through the naming of several species and geological formations in his honor, a testament to his lasting impact on scientific nomenclature:

- The Australian blind snake, Anilios broomi.

- The Triassic archosauromorph reptile, Prolacerta broomi.

- The rhinesuchid amphibian, Broomistega.

- The Permian dicynodont, Robertia broomiana.

- The millerettid, Broomia.

- The aloe plant species, Aloe broomii.

Broom's work continues to be a cornerstone in the study of human origins, and his discoveries remain fundamental to the understanding of our evolutionary past.