1. Overview

Rikidōzan, born Kim Sin-rak (김신락Korean), was a Korean-born Japanese professional wrestler and sumo wrestler, widely recognized as The Father of Puroresu (Japanese professional wrestling). Born in Korea under Japanese rule in 1924, he rose to prominence in post-World War II Japan, embodying the spirit of a national hero who could stand up to foreign opponents. His charismatic presence and powerful performances, particularly his signature karate chop, captivated the Japanese populace and significantly contributed to the popularization of television in the country. Beyond his athletic achievements, Rikidōzan was a shrewd businessman, investing in real estate and entertainment ventures. However, his life was also marked by a volatile personality, financial controversies, and alleged ties to organized crime, which culminated in his untimely death in 1963 from complications following a stabbing incident. His legacy is complex, encompassing both his immense influence on Japanese society and culture and the enduring controversies surrounding his character and dealings.

2. Early Life and Sumo Career

Rikidōzan's early life was marked by his Korean heritage and an eventual move to Japan, where he began a career in sumo wrestling before transitioning to professional wrestling.

2.1. Birth and Background

Rikidōzan was born Kim Sin-rak (김신락Korean) on November 14, 1924, in Shinpo-ri, Hongwon-gun, Kankyōnan-dō (South Hamgyong), in what was then Korea under Japanese rule and is now part of North Korea. He was the youngest son of Kim Sok-tee, a farm owner with a Confucian tradition, and his wife Chon Gi. In his youth, Kim participated in traditional Korean wrestling known as Ssireum, achieving third place in a local competition. It is believed that his actual birth year might have been one to two years earlier, as it was common practice in Korea at the time to report births later.

2.2. Move to Japan and Adoption

After his father's death in 1939, Kim Sin-rak left Korea for Japan in 1940, despite his mother's objections. He was recruited by Minosuke Momota, the father-in-law of a Japanese policeman from Ōmura, Nagasaki, who was a supporter of the Nishonoseki sumo stable and had previously recruited other Korean boys. Upon joining the Nishonoseki stable, Kim's Korean origins were initially noted on sumo ranking sheets, leading to harassment and racial discrimination. To circumvent this, he was adopted by Minosuke Momota and took the name Mitsuhiro Momota. A fabricated story was created stating he was born in Omura, Nagasaki. Despite these efforts, he did not acquire Japanese citizenship until 1951.

2.3. Sumo Career and Retirement

Kim Sin-rak debuted in sumo in May 1940, adopting the shikona (ring name) Rikidōzan Mitsuhiro (力道山 光浩Japanese). He ascended to the top makuuchi division in November 1946. In the June 1947 tournament, his second tournament in the top division, he achieved a record of 9 wins and 1 loss as a Maegashira 8, tying with three other wrestlers including Yokozuna Haguroyama Masaji, and participated in the championship playoff where he lost to Haguroyama. He continued to rise, reaching the rank of Sekiwake in May 1949. His career record in 23 tournaments was 135 wins and 82 losses. He received one Outstanding Performance Prize and earned two Kinboshi (victories over a Yokozuna) against Terukuni Manzo and Azumafuji Kin'ichi.

Rikidōzan's sumo career ended abruptly in September 1950 when he cut his own chonmage (topknot), signaling his retirement, which was officially attributed to paragonimiasis, a lung fluke infection. However, multiple factors contributed to his decision. He faced envy from senior wrestlers due to his rapid success despite his background. Racial discrimination was also a persistent issue. The immediate catalyst for his retirement was a heated financial dispute with his stable-master, Tamanoumi Daitarō. Rikidōzan believed his significant contributions to the stable warranted more financial support, which Tamanoumi denied. After retirement, he initially worked as a black marketeer, acquiring goods from departing US soldiers for the Korean War and selling them. His petition to return to sumo was rejected, leading him to work as a construction supervisor for his former patron, Shinsaku Nitta, who had connections to both the Allied occupation forces and the criminal underworld.

2.3.1. Sumo Records and Statistics

Rikidōzan's sumo career spanned 23 tournaments, from his debut in May 1940 until his retirement in September 1950. His highest rank achieved was Sekiwake.

| Rank | Record | Debut | Highest Rank | Retirement | Yusho (Championships) | Prizes | Kinboshi (Victories over Yokozuna) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sekiwake | 135-82-15 (23 tournaments) | May 1940 | Sekiwake (May 1949) | September 1950 | 1 (Makushita), 1 (Sandanme) | Outstanding Performance (1) | 2 (Azumafuji Kin'ichi, Terukuni Manzo) |

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Not held | Maegashira 17 | ||||||||||

| 1947 | Maegashira 8 | Maegashira 3 | ||||||||||

| 1948 | Maegashira 2 | Komusubi | ||||||||||

| 1949 | Komusubi | Sekiwake | Maegashira 2 | |||||||||

| 1950 | Komusubi | Sekiwake | Sekiwake | |||||||||

- The records indicate win-loss-absent. (S) indicates a Special Prize (Shukun-sho/Outstanding Performance Prize). P indicates participation in a championship playoff. '*' indicates a Kinboshi (victory over a Yokozuna).

3. Professional Wrestling Career

Rikidōzan's professional wrestling career saw him transform from a sumo wrestler into a national icon, establishing the foundation of professional wrestling in Japan.

3.1. Transition to Professional Wrestling

Rikidōzan's entry into professional wrestling was sparked by a charity drive organized by the Tokyo-based Torii Oasis Shriners Club in July 1951, which planned a wrestling tour for disabled children. Rikidōzan expressed interest in the sport and was invited to participate by Bobby Bruns, booker for Mid-Pacific Promotions, who was in Japan for the tour. After only one month of training, Rikidōzan made his professional wrestling debut on October 28, 1951, at Ryogoku Memorial Hall, wrestling Bruns to a ten-minute time-limit draw. He found the initial tour challenging due to his lack of stamina. In February 1952, Rikidōzan traveled to America for further training and experience, beginning a five-month stint with Mid-Pacific Promotions where he was trained by Oki Shikina in Honolulu. During his training in Hawaii in 1953, he reportedly challenged Lou Thesz but was defeated by a backdrop.

3.2. Rise to Stardom and National Hero

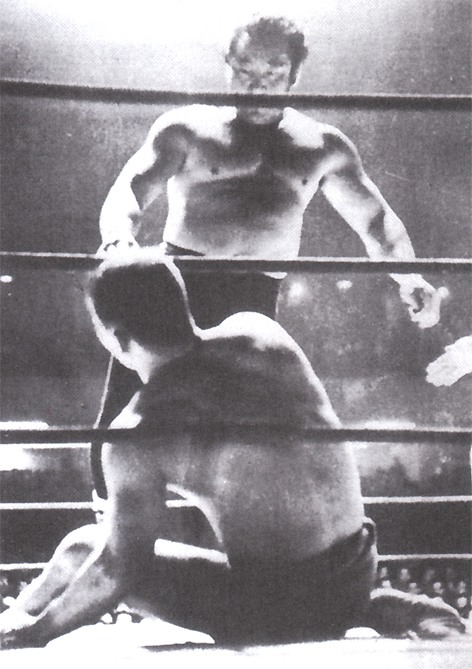

Rikidōzan's breakout performances occurred in 1954, notably when he teamed with famous judoka Masahiko Kimura against the Canadian Sharpe Brothers. This period coincided with a significant increase in television viewership in Japan. Rikidōzan further cemented his status as Japan's premier wrestling star by consistently defeating foreign wrestlers, becoming a major television sensation. In post-World War II Japan, where the nation was still recovering from defeat, Rikidōzan became an immensely popular figure. He was seen as a hero who could stand up to and defeat Americans, symbolically reclaiming pride for the Japanese people. His American opponents often played the role of villains, further enhancing Rikidōzan's heroic image. Interestingly, when he wrestled in America early in his career, he was initially booked as a villain but later became one of the first Japanese wrestlers cheered as a babyface (hero) in post-WWII America. His matches became cultural events, with two of his bouts ranking among the top ten highest-rated television programs in Japanese history. His October 6, 1957, hour-long draw with Lou Thesz for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship garnered an 87.0 rating, and his May 24, 1963, two-out-of-three falls draw with The Destroyer achieved a 67.0 rating, reaching an even larger audience as television ownership became more widespread. This made him arguably the "second most famous person in Japan after the Emperor."

3.3. Major Matches and Championships

Rikidōzan's career was defined by his acquisition of prestigious titles and his memorable rivalries. He gained international recognition on August 27, 1958, when he defeated Lou Thesz for the NWA International Heavyweight Championship in Japan. This victory built mutual respect with Thesz, who willingly "put over" Rikidōzan, boosting his reputation. Rikidōzan captured several NWA titles both in Japan and overseas. In 1953, he established the Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance (JWA), Japan's first professional wrestling promotion, with the help of Shinsaku Nitta and Sadao Nagata.

His first major feud was against Masahiko Kimura, the judoka whom Rikidōzan had invited to compete in professional wrestling. The infamous match between them on December 22, 1954, dubbed the "Showdown of Showa Era" (Showa no Ganryu-jima), was originally intended as a predetermined wrestling match. However, Rikidōzan reportedly deviated from the script after Kimura delivered a low blow, escalating the match into a brutal real fight where Rikidōzan relentlessly attacked Kimura with punches and harite (slaps), knocking him unconscious and causing him to bleed profusely. This incident sparked controversy and speculation about whether it was a "shoot" (real fight) or a "work" (staged). Rikidōzan later claimed it was a predetermined draw and exposed a note from Kimura, accusing him of breaking the agreement. Despite the controversy, the two later reconciled. Other notable feuds included his clashes with Lou Thesz (1957-1958), Freddie Blassie (1962), and The Destroyer (1963). His final match was a tag team bout on December 7, 1963, in Hamamatsu, teaming with Great Togo and Michiaki Yoshimura against The Destroyer, Buddy Austin, and Ilio DiPaolo.

3.4. Training of Disciples

Rikidōzan played a pivotal role in nurturing the next generation of Japanese professional wrestling talent. His most famous disciples included Antonio Inoki, Kintarō Ōki, and Giant Baba. Along with Mammoth Suzuki, they were known as the "Four Heavenly Kings" of Japan Pro Wrestling's youth.

Rikidōzan's training methods were notoriously harsh and often volatile. He was known for verbally and physically abusing his trainees, particularly Inoki, whom he would reportedly hit with a shoehorn, use as an "experiment" for dog training, force to drink large amounts of sake, and even strike with a golf club or throw an ashtray at. Inoki himself would later recount these experiences, stating he genuinely felt his life was in danger at times. However, Rikidōzan's wife, Keiko Tanaka, offered a different perspective, suggesting that Rikidōzan treated Inoki like his own son and that the strictness was a form of tough love, a reflection of his own "spartan" approach to education. She also revealed that Rikidōzan would often call Inoki to his home to discuss business matters, subtly exposing him to the entrepreneurial side of the wrestling industry, suggesting a desire to educate him beyond the ring.

Despite his harshness, Rikidōzan showed preferential treatment to Giant Baba, who had a strong physical build and prior fame as a professional baseball player. Rikidōzan saw Baba as an immediate star candidate. He believed in specific training methods, emphasizing bench presses, sit-ups, and Hindu squats. He would instruct disciples to focus intensely on specific muscle groups for extended periods, as seen when he told Hisashi Shinma to perform only bench presses for three months, leading to significant strength gains. Rikidōzan also believed sumo training was beneficial for building mass, and just before his death, he had arranged for Inoki to temporarily join a sumo stable, a plan that was never realized.

Of all his disciples, it was rumored that Rikidōzan held the most genuine affection for Kintarō Ōki, who, like himself, was of Korean descent. Rikidōzan also had high expectations for Mammoth Suzuki as a wrestler. He even used his political connections, including then LDP Vice President Banboku Ōno, to secure Ōki's residency in Japan after Ōki had illegally entered the country from Korea in 1958, though he forbade Ōki from using his Korean name.

3.5. Signature Moves

Rikidōzan's signature moves were widely known and became iconic in Japanese professional wrestling:

- Karate Chop (空手チョップJapanese, Karate Choppu): His absolute finishing move and his most famous technique. It was derived from sumo's harite (open-hand slap) rather than traditional karate. He reportedly developed it with the input of his Korean-born friend, karateka Hideo Nakamura, whom he called "Hyung Nim" (형님Korean, older brother). Rikidōzan employed variations such as the "Kesa-giri Chop" (aimed at the carotid artery or collarbone) and the "Horizontal Chop" or "Reverse Horizontal Chop" (a horizontal swing to the opponent's chest).

- Headscissors Whip: Despite his stout build, Rikidōzan was agile and acrobatic. He would jump and scissor his opponent's head with his legs, using the momentum to throw them or transition into a headscissors submission.

- Harite (Open-hand Slap): A powerful slap originating from sumo, which he effectively used in wrestling, notably in his match against Masahiko Kimura.

- Backdrop: A move he learned from Lou Thesz. In the latter part of his career, it became another primary finishing move alongside the Karate Chop.

- Reverse Prawn Hold (Gyakuebi Gatame): Often used as a finishing move against younger or lesser opponents.

- Scooping Throw (Sukui Nage): A sumo technique he frequently used as a transitional move in his matches.

- Headlock: Leveraging his arm strength cultivated in sumo, Rikidōzan's headlock was highly effective.

- Bodyslam

- Body Press

4. Business Ventures

Beyond the wrestling ring, Rikidōzan was an ambitious and successful businessman, diversifying into various industries.

4.1. Real Estate and Entertainment Businesses

Rikidōzan leveraged his fame and wealth to acquire numerous properties and establish diverse businesses. In Akasaka, Tokyo, he owned "Riki Mansion," a luxury apartment building that also served as his residence, recognizable by the large "R" on its facade. He also owned the "Club Riki" nightclub in Akasaka. In Shibuya, Tokyo, he developed the "Riki Sports Palace," a nine-story complex that featured a permanent wrestling venue, a bowling alley, a pool hall, and a restaurant known as "Riki Restaurant," along with a Turkish-style steam bath ("Riki Turco"). He also ventured into boxing promotions.

4.2. Other Business Initiatives

Rikidōzan harbored grand plans for further expansion. Shortly before his death, he began construction on a large-scale golf course called "Lakeside Country Club" by Lake Sagami in Kanagawa Prefecture. This ambitious project was envisioned to include a car race track, a shooting range, an indoor ice-skating rink, and a motel. However, due to his untimely death, the project remained incomplete. The land was later sold and developed into Sagamiko Resort Pleasure Forest. He also purchased land in Aburatsubo, Miura Peninsula, with plans to build a marine resort for families.

Rikidōzan's businesses were largely run under his charismatic, one-man leadership. His sudden death caused significant disruption, leading to the collapse or sale of many of his ventures. The Riki Sports Palace, for instance, suffered from financial difficulties and was eventually sold in 1967. This sale also contributed to internal conflicts within Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance, leading to the departure of Masa Saito and the formation of International Pro Wrestling. Rikidōzan's financial dealings were not without controversy; he was once investigated for insurance fraud in 1949 after a fishing boat he co-owned caught fire, though he was eventually cleared. His financial situation was often precarious despite his assets, reportedly carrying significant debt, with estimates reaching 450.00 M JPY, and owing millions in unpaid taxes, including an inheritance tax on his estate upwards of 20.00 M JPY (equivalent to 96.90 M JPY or 665.00 K USD as of 2023), which led to the national confiscation of his personal estate after his death. This financial strain was partly due to the high costs of inviting top foreign wrestlers during a period of a weak Japanese yen and his lavish spending.

5. Personal Life and Character

Rikidōzan's personal life was as complex and tumultuous as his public persona, marked by multiple relationships, a volatile temperament, and controversies that often contrasted with his image as a national hero.

5.1. Marriages and Family

Rikidōzan was involved in multiple marital relationships throughout his life. It is believed he married four times. His first marriage and children were in Korea before he moved to Japan. He later had relationships with two geisha in Japan-one in Kyoto, who was the mother of his sons, and another in Nihonbashi, who raised his children. His final marriage was to Keiko Tanaka, a former Japan Airlines flight attendant, shortly before his death. This marriage lasted only ten months. Rikidōzan was reportedly deeply infatuated with Tanaka and ended his other relationships for her. His Korean heritage was largely concealed from the public during his career in Japan; however, a 1984 article in Weekly Playboy sensationally revealed his Korean origin and prior marriages, which was considered taboo at the time.

Rikidōzan had three sons and two daughters. His sons, Yoshihiro Momota and Mitsuo Momota, both became professional wrestlers (Yoshihiro transitioned from a ring announcer), and later became influential figures in the Japanese wrestling world, participating in the management of All Japan Pro Wrestling after Giant Baba established it. Both sons stated they learned of their father's Korean heritage only after his death. Rikidōzan's grandson, Chikara Momota (Mitsuo's son), also became a professional wrestler. Another grandson, Kei Tamura (his daughter's son), was a high school baseball player. Rikidōzan's son-in-law, Bak Myeong-cheol (박명철Korean), the husband of his daughter Park Young-suk, became a high-ranking official in North Korea, serving as a member of the National Defence Commission.

5.2. Personality and Controversies

Rikidōzan was known for his rough and often volatile personality, with extreme mood swings. When in a good mood, he was generous, known to leave tips of as much as 10.00 K JPY (equivalent to a university graduate's monthly salary at the time) for bar staff. However, when his mood soured, violent incidents at bars were almost a daily occurrence, often suppressed with monetary settlements. Newspaper reports from 1957 frequently featured headlines like "Rikidōzan goes wild again." He was also observed to be physically abusive, reportedly breaking glass tables and even eating thin glass cups when severely intoxicated.

His public image suffered from his heavy drinking habits and the perception that professional wrestling was staged, especially when he was seen socializing with opponents he had "fought" just hours earlier. In one instance, he confronted Cuban baseball player Roberto Barbon of the Hankyu Braves, who had publicly called professional wrestling fake, threatening violence until Barbon apologized. In his later years, Rikidōzan's physical health deteriorated, leading him to abuse painkillers and take stimulants before and after matches, which may have exacerbated his aggressive behavior.

Rikidōzan's alleged associations with Yakuza organizations were a persistent controversy. He had ties to various criminal groups through his business ventures and wrestling promotions. While he was instrumental in establishing professional wrestling in Japan, an industry that was closely intertwined with the underworld in the 1950s due to insufficient legal frameworks against such organizations, he often acted without sufficient regard for these powerful figures. This led to numerous troubles, including being nearly held captive by the Yamaguchi-gumi, being pursued by the Ando-gumi, and even reportedly throwing a Philippine mafia leader into a river, which often put his life at risk. Despite these dangers, he continued to engage in reckless behavior that many believed could have been avoided.

5.3. Hobbies and Interests

In his leisure time, Rikidōzan enjoyed hunting, possessing several legitimate hunting guns at the time of his death. His autobiography even claimed he made his wife carry a handgun. He also took an interest in Shogi, the Japanese board game, and became acquainted with professional shogi player Kusama Matsuji, who awarded him an amateur third dan certificate. However, it is said he rarely played, making his actual skill level uncertain.

6. Death

Rikidōzan's death was a highly publicized event that shocked Japan, marked by a violent altercation, medical complications, and lingering questions.

6.1. Stabbing Incident

On December 8, 1963, at approximately 10:30 PM, Rikidōzan was involved in an altercation with Katsushi Murata, a member of the ninkyō dantai (chivalrous organization) Sumiyoshi-ikka, a Yakuza syndicate, at the "New Latin Quarter" nightclub in Akasaka, Tokyo. The dispute reportedly began when Rikidōzan accused Murata of stepping on his shoe and demanded an apology. Murata denied it, leading to a heated argument. Rikidōzan then punched Murata, knocking him against a wall, and proceeded to mount him and continue punching him on the ground. Fearing for his life, Murata drew a mountaineering knife and stabbed Rikidōzan once in the lower left abdomen. Both men immediately left the scene.

6.2. Medical Complications and Passing

Rikidōzan was taken to Sannoh Hospital, where a doctor initially deemed the wound non-serious but advised surgery. The first surgery was successful, and he returned home. However, against strict doctor's orders, Rikidōzan reportedly began eating and drinking the same day, sending his assistant to buy sushi and sake. His wife, Keiko Tanaka, later denied this, stating she and nurses attended to him constantly. However, his attendant, Yonejiro Tanaka, later confirmed that Rikidōzan had asked him to buy whiskey, suggesting he consumed alcohol and possibly food secretly. This behavior worsened his condition, leading to severe complications.

On December 15, seven days after the stabbing, Rikidōzan developed Peritonitis, a serious infection of the abdominal lining, and intestinal obstruction. He underwent a second surgery at 2:30 PM. Before the operation, he reportedly told his wife, "No matter how much it costs, use any medicine. Tell the doctor to give me the best treatment. I don't want to die yet." Although the surgery was reported as successful, Rikidōzan fell into a coma and died at approximately 9:50 PM. He was 39 years old.

The official cause of death was declared as perforating pyogenic peritonitis, leading to septic shock. The operating surgeon indicated that the presence of 200-300cc of blood in the abdominal cavity from the initial stabbing, coupled with intestinal contents spilling out and bacteria introduced by the rusty knife, could not be fully sterilized. However, various doubts and theories surrounded his death. An early theory suggested medical malpractice, specifically that the anesthesiologist failed to intubate his trachea after injecting a muscle relaxant, leading to asphyxiation. This theory gained traction from a book published 30 years after his death, citing a medical student's hearsay. However, a 2019 report debunked this, stating that medical students were not involved in anesthesia in general hospitals at that time, and there were no records supporting an intubation failure. Instead, the 2019 report concluded that septic shock from the peritonitis was the most plausible cause. Additionally, Rikidōzan's attendant Mitsu Hirai later recounted seeing Rikidōzan clutching his chest in pain during golf shortly before the incident, and Rikidōzan had told him not to tell anyone, suggesting pre-existing internal issues that were corroborated by the autopsy revealing a very poor state of his internal organs.

6.3. Funeral and Aftermath

Rikidōzan's funeral was held on December 20, 1963, at Ikegami Honmonji Temple in Ōta, Tokyo. More than 10,000 people attended, including his disciples Antonio Inoki, Giant Baba, and Kintarō Ōki, as well as numerous opponents and prominent figures from various fields such as Yoshio Kodama, Matsutaro Shoriki, Banjun Bando, and Hibari Misora. A bust of Rikidōzan stands at his grave in Honmonji Temple, with a portion of his ashes also interred at his adopted family's grave in Chōanji Temple in Omura, Nagasaki.

Katsushi Murata was found guilty of Manslaughter in October 1964 and served eight years in prison before being released in 1972. After his release, Murata reportedly visited Rikidōzan's grave every year on December 15, the anniversary of his death, and yearly called Rikidōzan's sons to apologize. Murata eventually rose to a high rank within the yakuza before his death from natural causes (diabetes) on April 9, 2013, at the age of 74.

7. Legacy and Reception

Rikidōzan's legacy is immense, shaping the cultural and sporting landscape of post-war Japan, though it is also tempered by criticism and controversies surrounding his personal conduct and associations.

7.1. Influence on Japanese Society and Culture

Rikidōzan emerged as a colossal figure in post-war Japan, serving as a powerful cultural icon who significantly uplifted national morale. In a country grappling with the psychological scars of defeat, his victories over foreign (especially American) wrestlers resonated deeply, symbolizing a reclaiming of Japanese pride and strength. He was so popular that it was famously said, "Even if you don't know the Prime Minister's name, you know Rikidōzan's." An anecdote from 1959 illustrates this perfectly: when then-Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi arrived at Gifu Station for a political campaign, a large crowd of listeners immediately abandoned him upon seeing Rikidōzan disembark from a train on the opposite platform.

His matches, broadcast live, played a crucial role in the widespread adoption of television in Japan. Families and communities would gather around street televisions to watch him fight, making him a catalyst for the new medium's popularity. His influence extended even to the criminal underworld, with the Tosei-kai, a yakuza group, reportedly amassing significant wealth through his wrestling promotions, as detailed in Robert Whiting's "Tokyo Underworld."

7.2. Contribution to Professional Wrestling

Rikidōzan is universally acknowledged as the foundational figure in establishing and shaping professional wrestling in Japan, earning him the title of "The Father of Puroresu." His vision led to the creation of the Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance (JWA) in 1953, the nation's first major wrestling promotion. He not only dominated the ring but also dedicated himself to training the next generation of Japanese wrestling stars, including legends like Giant Baba, Antonio Inoki, and Kintarō Ōki. His star power and charisma were unparalleled, laying the groundwork for the enduring popularity of professional wrestling in Japan for decades to come.

7.3. Honors and Awards

Rikidōzan's significant contributions to professional wrestling have been widely recognized through numerous posthumous honors:

- He was inducted into the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame as one of its first members in 1996.

- In 2006, he was inducted into the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum.

- The WWE Hall of Fame included him in its "Legacy Wing" class of 2017.

- In 2011, he was inducted into the NWA Hall of Fame.

- In 2021, he was inducted into the International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame.

- In 2002, wrestling journalist John M. Molinaro, with input from Dave Meltzer and Jeff Marek, ranked Rikidōzan as the 3rd greatest professional wrestler of all time in the magazine article "100 Wrestlers of All Time," placing him behind Ric Flair and his rival Lou Thesz.

- In 2024, Maple Leaf Pro Wrestling established the PWA Champion's Grail, merging the lineage of a 1962 trophy won by Rikidōzan and Toyonobori with a more modern championship.

7.4. Criticism and Controversies

Despite his heroic public image, Rikidōzan's career and personal life were not without significant criticism and controversy. His volatile and often violent personality, particularly when drunk, was a constant source of trouble, leading to frequent altercations and public disputes that often required financial settlements to avoid legal repercussions. While his rough conduct might be partially attributed to the stimulants he took later in his career, it also contributed to public skepticism about the legitimacy of professional wrestling, especially when he was seen socializing with his in-ring opponents shortly after a "fight."

His alleged ties to organized crime were a major point of contention. While he was integral to an industry that often operated within the underworld's sphere of influence in post-war Japan, his repeated disregard for prominent yakuza figures led to life-threatening situations, including conflicts with the Yamaguchi-gumi, Ando-gumi, and even the Philippine mafia. Critics argue that many of these troubles could have been avoided had Rikidōzan exercised more discretion.

Financially, Rikidōzan's business acumen was double-edged. While he built an empire, he also incurred massive debts, reportedly 450.00 M JPY, due to lavish spending, expensive foreign talent bookings, and alleged "pinhane" (extortion) by yakuza groups in Kansai and Kyushu. His 1949 insurance fraud investigation, though he was cleared, left a lasting negative mark on his reputation. Furthermore, there were reports of financial disputes with his top disciple, Giant Baba, regarding earnings, which, combined with alleged jealousy from Rikidōzan over Baba's rising talent, led Baba to privately describe Rikidōzan as a person "with no good qualities as a human being." These aspects present a more complex and critical view of the national hero, highlighting the darker side of his immense influence and character.

8. Family

Rikidōzan's family included several individuals who made their own marks, some with ties to the professional wrestling world and even North Korean politics.

His eldest son, Yoshihiro Momota, and second son, Mitsuo Momota, both followed him into professional wrestling. Mitsuo began his career in 1970 and wrestled until 2021, although he never achieved the same level of fame as his father, despite holding the World Junior Heavyweight Championship in 1989. Yoshihiro initially served as a ring announcer before becoming a wrestler. After Rikidōzan's death, his sons discovered their father's Korean heritage. Both Mitsuo and Yoshihiro became respected figures in the wrestling industry, serving as executives in All Japan Pro Wrestling after its founding by Giant Baba.

Rikidōzan's grandson, Chikara Momota (Mitsuo's son), made his in-ring debut in 2013, continuing the wrestling legacy. Another grandson, Kei Tamura, the son of Rikidōzan's daughter with Keiko Tanaka, became a high school baseball player for Keio Senior High School, earning recognition for his performance in the Koshien Tournament.

Rikidōzan's son-in-law, Bak Myeong-cheol (박명철Korean), who married his daughter Park Young-suk (born from his first marriage in Korea), rose to prominence in North Korea. As of early 2009, Bak Myeong-cheol served as a member of the National Defence Commission of North Korea, and his younger sister, Park Myong-son, was the vice secretary of the Light Industry Division of the Workers' Party of Korea. This connection highlights Rikidōzan's continuing ties to his Korean origins even after his death.

9. In Popular Culture

Rikidōzan's larger-than-life persona and cultural impact led to his frequent portrayal and reference in various forms of media.

He appeared in at least 29 films, often playing himself. Notable appearances include:

- Otsukisama ni wa warui kedo (1954)

- Yagate Aozora (1955)

- Rikidōzan monogatari dotō no otoko (Rikidōzan Story: Man of Billowing Waves, 1955)

- Ikare! Rikidōzan (Rage! Rikidōzan, 1956), a film that controversially depicted him being stabbed in a nightclub fight with yakuza, a scenario eerily similar to his actual death years later.

- Junjo Butai (1957)

- Gekito (Fierce Battle, 1959), which was his last film appearance before his death.

He was also the subject of several works:

- The documentary film Pro Wrestling W League: Chinurareta Ōja (Pro Wrestling W League: Blood-stained King, 1968).

- The documentary film The Rikidōzan (1983) directed by Tomoyasu Takahashi.

- The 2004 South Korean-Japanese co-production film Rikidōzan, starring Sol Kyung-gu as Rikidōzan.

- Documentary films about him have also been produced in North Korea.

- A 2022 NHK documentary titled Another Stories: Rikidōzan's Unknown Truth explored various aspects of his life.

In music, Southern All Stars released a song titled "Yuke!! Rikidōzan" (Go!! Rikidōzan) as a B-side in 1993. His image was also used in commercials, including for Ono Pharmaceutical's "Riki Hormo" (around 1962) and later for Rohto Pharmaceutical's "Pansiron" (around 1990), featuring archival footage of his matches.

His trademark black tights were rumored to conceal an old injury from a severe hazing incident during his sumo days, when his younger disciple Wakanohana Kanji I bit his thigh. The custom of eating raw horse meat (basashi) with spicy miso in Aizu-Wakamatsu, Fukushima Prefecture, is said to have originated from Rikidōzan ordering and eating raw horse meat with chili miso at a local butcher shop during a wrestling tour in 1955.

10. Championships and Accomplishments

Rikidōzan accumulated numerous championships and accolades throughout his professional wrestling career.

| Championship/Awarding Body | Championship/Award | Times Won | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance | All Asia Heavyweight Championship | 1 | 1955 |

| All Asia Tag Team Championship | 4 | With Toyonobori (4) | |

| JWA All Japan Tag Team Championship | 1 | With Toyonobori | |

| NWA International Heavyweight Championship | 1 | 1958 | |

| Japanese Heavyweight Championship | 1 | 1954 | |

| World Big League (Tournament) | 5 | 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963 | |

| International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame | Induction | Class of 2021 | 2021 |

| Maple Leaf Pro Wrestling | PWA Champion's Grail | 1 | 1962 (revived 2024) |

| Mid-Pacific Promotions | NWA Hawaii Tag Team Championship | 3 | With Bobby Bruns (1), Azumafuji Kin'ichi (1), Koukichi Endoh (1) |

| National Wrestling Alliance | NWA Hall of Fame | Class of 2011 | 2011 |

| NWA San Francisco | NWA Pacific Coast Tag Team Championship (San Francisco version) | 1 | With Dennis Clary |

| NWA World Tag Team Championship (San Francisco version) | 1 | With Koukichi Endoh | |

| North American Wrestling Alliance / Worldwide Wrestling Associates / NWA Hollywood Wrestling | WWA World Heavyweight Championship | 1 | 1962 |

| Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum | Induction | Class of 2006 | 2006 |

| Wrestling Observer Newsletter | Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame | Class of 1996 | 1996 |

| WWE | WWE Hall of Fame | Class of 2017 (Legacy Wing) | 2017 |