1. Overview

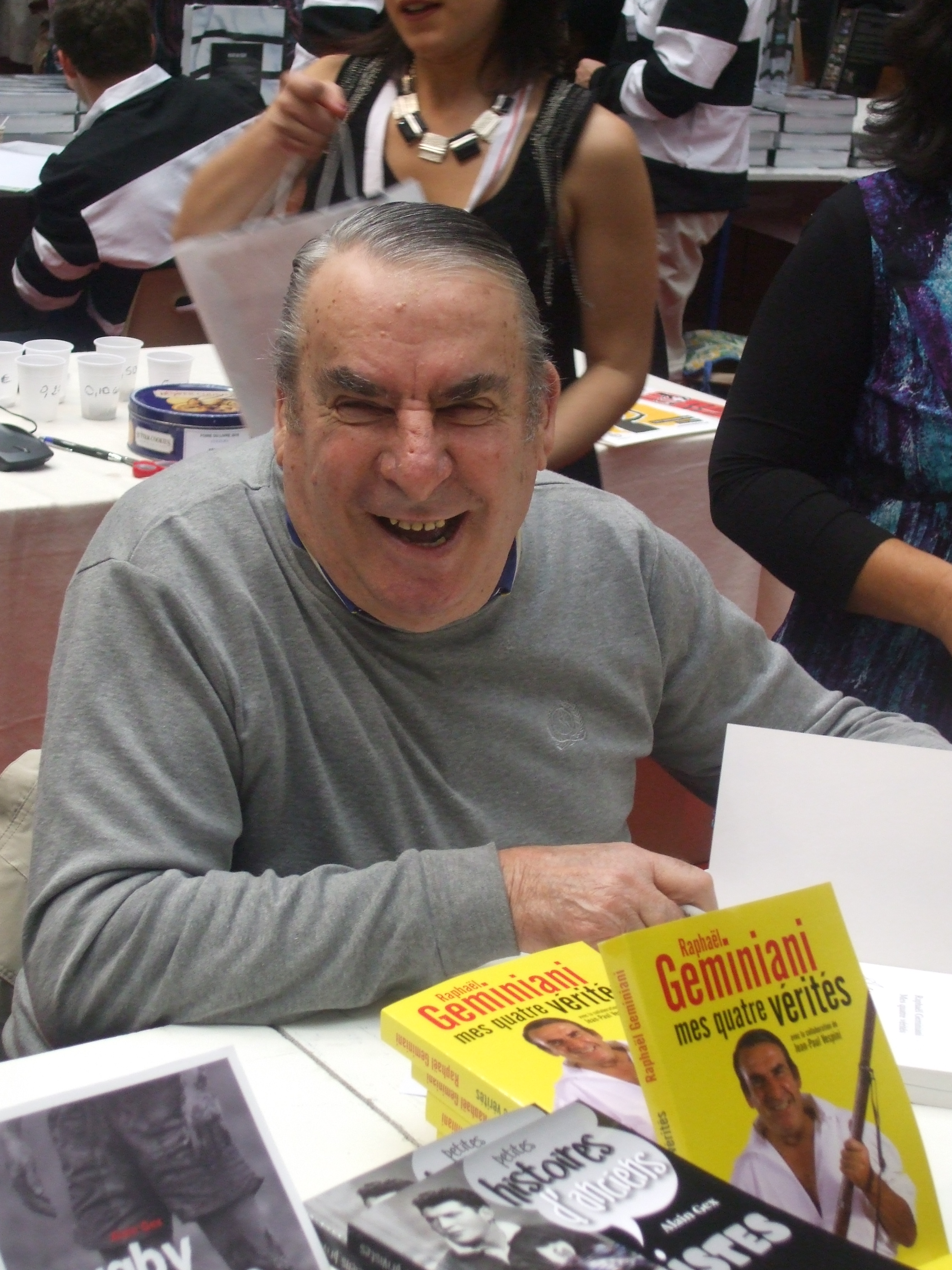

Raphaël Géminiani (1925-2024) was a prominent French road bicycle racer and later a highly influential directeur sportif. Born in Clermont-Ferrand, he was one of the most colorful and outspoken figures in professional cycling for over half a century. Known for his strong, often confrontational personality, he earned the nickname Le Grand FusilThe Big Gun or Top GunFrench. His career as a rider spanned from 1946 to 1960, during which he achieved three podium finishes in the Grand Tours, including second place in the Tour de France and third in the Vuelta a España, alongside multiple stage wins and mountains classification titles. After retiring from racing, Géminiani transitioned into management, notably guiding Jacques Anquetil to numerous victories, including four Tour de France titles. His impact on French cycling history is significant, marked by his candid views on the sport, including his controversial stance on doping, and his advocacy for traditional racing values.

2. Background and Early Life

Raphaël Géminiani was born on 12 June 1925, in Clermont-Ferrand, France. He was one of four children born to Italian immigrants. His father, Giovanni, had brought the family to France in 1920, fleeing fascism in Italy after his bicycle factory in Lugo burned down. Upon settling in Clermont-Ferrand, Giovanni established a new bicycle shop and insisted that his family speak French from then on.

Raphaël's elder brother, Angelo, was a skilled amateur rider. Raphaël himself left school at the age of 12 to work in his father's shop, where he specialized in building bicycle wheels. Initially, his father was skeptical of Raphaël's potential as a cyclist, remarking on his skinny legs and suggesting that racing was Angelo's domain. Despite this, Raphaël began racing as a boy during the German occupation of France. In 1943, at 16, he won the first round of the Premier Pas Dunlop, a youth championship, and finished third in the next heat, qualifying for the final held on 3 June 1943, in Montluçon. Following his father's advice, he launched a decisive attack on a hill 9.3 mile (15 km) from the finish, securing the win. Notably, Louison Bobet, whose destiny would later be closely linked with Géminiani's, finished sixth in the same race. After the war, Géminiani continued racing in mixed amateur-professional events, first locally and then nationally, before signing his first professional contract in 1946 with the Métropole team, managed by Romain Bellenger.

3. Racing Career

Raphaël Géminiani's professional cycling career spanned from 1946 to 1960, marked by significant achievements, fierce rivalries, and a distinctive personality that earned him the nickname Le Grand FusilThe Big Gun or Top GunFrench.

3.1. Professional Debut and Early Tours de France

Géminiani's professional debut came in 1946. His first Tour de France in 1947 proved challenging. The initial stage from Paris to Lille was held during one of the hottest summers in decades, with roads still in poor condition from the war, often cobbled. Géminiani finished 20 minutes behind the leaders. The next day, on the stage to Brussels, he and eight other riders maintained a breakaway for 62 mile (100 km), but by the time they reached the Belgian capital, he was 30 minutes behind. The extreme heat caused many riders to drop out. The situation worsened on the stage from Brussels to Luxembourg, which was advertised as 227 mile (365 km) but was over 249 mile (400 km). Riders desperately sought drinks from wayside cafés and fought for access to drinking fountains, with firemen even spraying water on competitors as they neared Luxembourg. Géminiani finished 50 minutes down and was too exhausted to eat dinner. On the stage to Strasbourg, his face became so bloated and blistered that his vision was impaired. He recounted stopping by a farm to drink dirty water from a cattle trough, which led to him contracting foot-and-mouth disease. The following morning, feverish and nearly blind, he withdrew from the race and was hospitalized, taking two days to reach Clermont-Ferrand and another six to recover.

His selection for the Southwest-Centre team and later the national team for the 1948 Tour de France drew criticism, particularly in his home region of Auvergne, where rumors suggested his father had bribed selectors. Insults were hurled at him when he beat local favorite Jean Blanc in a race just three days before the Tour began. Despite this, Géminiani started strong, placing sixth after four days. Although he lost ground in the mountains, he managed to stay with stronger riders like Jean Robic, Louison Bobet, and Gino Bartali. He was 14th when the race reached Cannes and, despite a series of flat tires on the stage to Briançon, he finished 15th overall, having supported his teammate Guy Lapébie to third place. His performance shifted public perception in Clermont-Ferrand, where fans greeted him at the station and paraded him through the city in an open car.

3.2. Grand Tour Performances

Géminiani was a consistent performer in the Grand Tours, achieving notable overall placings and demonstrating his endurance across multiple major races. He secured three podium finishes throughout his career. In the 1951 Tour de France, he achieved his best overall result, finishing second behind Hugo Koblet. He also secured third place in the 1955 Vuelta a España. In the Tour de France, besides his second place in 1951, he finished fourth in 1950 and third in 1958. He also placed sixth in 1955 and ninth in 1953. In the Giro d'Italia, he finished fourth in 1955, fifth in 1957, eighth in 1958, and ninth in 1952. He also achieved fifth place in the 1957 Vuelta a España. A remarkable feat in 1955 saw Géminiani finish in the top 10 of all three Grand Tours (Tour de France, Giro d'Italia, and Vuelta a España), a rare achievement only equaled by Gastone Nencini in 1957 and not since.

3.3. Key Victories and Classifications

Géminiani's career was marked by significant individual victories and classification successes. He won the mountains classification in the Tour de France in 1951, and the mountains classification in the Giro d'Italia in both 1951 and 1957. In 1953, he became the French National Road Race Champion.

He secured seven individual stage victories in the Tour de France between 1949 and 1955:

- 1949: Stage 19

- 1950: Stages 17 and 19

- 1951: Stage 9

- 1952: Stages 8 and 17

- 1955: Stage 9

He also wore the yellow jersey as the leader of the general classification for four days during his Tour de France participations. Beyond the Grand Tours, Géminiani's notable wins include:

- 1943: National Junior Road Championships

- 1946: Ambert

- 1949: Circuit des villes d'eaux d'Auvergne, Tour de Corrèze

- 1950: GP de Marmignolles, Polymultipliée

- 1951: Overall Grand Prix du Midi Libre, Polymultipliée

- 1956: Abidjan, Bol d'Or des Monédières Chaumeil

- 1957: Bol d'Or des Monédières Chaumeil, Quilan, Tulle

- 1958: Bol d'Or des Monédières Chaumeil, Thiviers, Tulle

- 1959: GP d'Alger, and two team time trial stages (1a and 13) in the 1959 Vuelta a España.

3.4. Personality and On-the-Bike Incidents

Géminiani's strong, often confrontational personality was a defining characteristic of his racing career, earning him the nickname Le Grand FusilThe Big Gun or Top GunFrench. His quick temper led to several memorable incidents.

In the 1953 Tour de France, a heated argument erupted between Géminiani and Louison Bobet during dinner. The French national team had attacked rival Jean Robic on the stage from Albi to Béziers. The battling continued all day, culminating in a sprint won by Nello Lauredi, with Géminiani finishing second. This denied Bobet a time bonus that would have helped him win the stage. Bobet's accusations infuriated Géminiani, who, according to legend, emptied his plate onto Bobet's head. Bobet, known for his emotional nature, reportedly burst into tears and left the table.

Another incident showcasing his temper occurred during the 1952 Tour de France after a stage to Namur. Jean Robic held an impromptu press conference in his bath, where he boasted about "playing dead" to avoid work and having better chances than Géminiani. Overhearing this, Géminiani pushed through journalists and held Robic's head underwater three times. The commotion drew Marcel Bidot and Raymond Le Bert, who separated them, with Le Bert urging them to work together. This confrontation, surprisingly, led to a rapprochement between Géminiani and Bobet, who shared facing bedrooms. Géminiani subsequently became a mentor to Bobet, guiding him through races and helping him devise battle plans, notably assisting him in his three Tour de France victories.

Géminiani's fiery nature extended to spectators. In the 1957 Giro d'Italia, while climbing, he reported that some spectators were pushing him while others were punching him in the back. In response, he took off his pump and struck one of them, causing the person to lose five teeth.

A famous anecdote involves his warning to Ferdi Kubler on Mont Ventoux during the 1955 Tour de France. On a scorching day with temperatures reaching 104 °F (40 °C), Kubler launched a powerful attack. Géminiani cautioned him, "Steady, Ferdi! The Ventoux isn't like other climbs." Kubler, in shaky French, retorted, "Ferdi also not champion like others." Kubler later denied this exchange, calling Géminiani a "gossip" and "the telephone" in the peloton, though he acknowledged they were good friends.

The 1958 Tour de France became known as the "Judas Tour" due to a bitter dispute involving Géminiani. He was leading the race when Charly Gaul of Luxembourg, a formidable climber, attacked alone in a rainstorm on the 21st stage, overcoming a 15 minutes deficit to displace Géminiani. Géminiani accused the French national team, particularly Bobet, of betrayal (a biblical reference to Judas Iscariot) for failing to support him. The rivalry was intensified because Bobet rode for the national team while Géminiani rode for Centre-Midi, yet Géminiani believed French riders should support each other against foreign competitors. Géminiani was also bitter about being excluded from Bobet's team due to selection politics, stating he had always honored the French jersey. At the start of the race, a fan in Brussels gave him a donkey, which Géminiani famously named Marcel, after the French selector Marcel Bidot who had kept him off the national team.

4. Managerial Career

After retiring as a rider in 1960, Raphaël Géminiani seamlessly transitioned into a highly successful career as a directeur sportif and team manager, leaving a lasting mark on the sport through his leadership and strategic acumen. He continued to be active in management until 1986.

4.1. Team Management and Sponsorship

Géminiani's foray into team management began by sponsoring himself and other riders to promote bicycles made under his own name, "R. Géminiani." However, upon signing Jacques Anquetil, he realized the need for greater financial backing than the traditional cycle industry could provide. This led him to seek "extra-sportif" sponsors, a controversial move at the time.

In 1962, Géminiani sold his team to the St-Raphaël apéritif company, coinciding with the Tour de France's decision to open to commercial teams. This move was met with strong opposition from Tour organizers Jacques Goddet and Félix Lévitan, who feared powerful rivals and a reduction in advertising revenue for their newspaper, L'Équipe. Géminiani faced threats of suspension. He attempted to argue that "Raphaël" in the team name referred to himself, not the company. The dispute escalated to the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI). According to Géminiani, UCI president Achille Joinard, who favored commercial sponsorship and had his own disagreements with Lévitan, advised him to appear at the start in an ordinary jersey, then switch to the St-Raphaël kit just before the race began. Joinard reportedly promised to send a telegram forbidding his start, but ensured it would arrive only after the race had commenced.

After St-Raphaël withdrew its sponsorship at the end of 1964, Géminiani sold his team to the French division of Ford, the car manufacturer. In 1969, he transitioned the team's sponsorship to Bic, the cigarette lighter and ballpoint pen company, founded by Marcel Bich. The Bic team, under Géminiani's management, featured prominent riders such as Anquetil, Lucien Aimar, Julio Jiménez, Jean Stablinski, Rolf Wolfshohl, Joaquim Agostinho, and later, Luis Ocaña. Ocaña notably won the 1973 Tour de France while riding for Bic. However, the team's seven-year run ended when Baron Bich discovered that Ocaña had complained about not being paid, with the money reportedly held in a company account managed by Géminiani. The Baron, known for his strict principles, immediately withdrew sponsorship.

In 1985, Géminiani became the directeur sportif for the La Redoute team, guiding Stephen Roche to a third-place finish in the 1985 Tour de France. He specifically advised Roche to attack on the 18th stage after reviewing the route. When La Redoute retired from the sport at the end of that year, Roche brought Géminiani with him to his new team. In 1986, Géminiani served as the manager for Café de Colombia.

4.2. Mentoring and Coaching Key Riders

Géminiani's managerial career reached its zenith through his partnership with Jacques Anquetil, primarily with the St-Raphaël and Ford-France teams. Together, they achieved remarkable success, including four Tour de France victories, two Giro d'Italia titles, the Dauphiné-Libéré, and the monumental Bordeaux-Paris race.

Géminiani was a staunch defender of Anquetil, who often faced public criticism for being perceived as cold or a "calculator." Géminiani vehemently countered these views, stating that Anquetil was "a monster of courage" who suffered immensely in the mountains despite not being a natural climber, but used "bluffing" and "guts" to overcome his rivals. He recalled seeing Anquetil crying in his hotel room after enduring spitting and insults from spectators.

In 1965, to silence critics who gave more credit to Raymond Poulidor for dropping Anquetil on the Puy-de-Dôme the previous year than to Anquetil for winning the entire Tour, Géminiani persuaded Anquetil to attempt the unprecedented "double": winning the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré and, the very next day, the 346 mile (557 km) Bordeaux-Paris race. Anquetil won the Dauphiné at 3 PM despite bad weather. After two hours of interviews, he flew from Nîmes to Bordeaux at 6:30 PM on a private plane. At midnight, he ate his pre-race meal and then headed to the start. During the night, Anquetil suffered from stomach cramps and was on the verge of retiring. Géminiani, known for his provocative methods, swore at Anquetil and called him "a great poof" to offend his pride and motivate him to continue. Anquetil felt better as morning approached and responded to an attack by Tom Simpson, followed by his own teammate Jean Stablinski. Anquetil and Stablinski alternately attacked Simpson, exhausting him, and Anquetil ultimately won at the Parc des Princes, with Stablinski finishing 57 seconds later, just ahead of Simpson. There were rumors that the private jet used to transport Anquetil to Bordeaux was provided through state funds on the orders of Charles de Gaulle, though Géminiani mentioned this in his biography without confirming or denying it.

Beyond Anquetil, Géminiani also played a crucial role in mentoring and guiding Louison Bobet. Despite their earlier clashes, Géminiani warmed to Bobet and became instrumental in his three Tour de France victories, "tele-commanding his victories and drawing up his battle plans."

5. Relationships and Personal Life

Raphaël Géminiani's long career in cycling was deeply intertwined with significant personal relationships and rivalries that shaped the sport's landscape during his era.

5.1. Friendship with Fausto Coppi

Géminiani shared a close bond with Italian cycling legend Fausto Coppi. In December 1959, both were invited to Burkina Faso (then the French colony of Haute Volta) by President Maurice Yaméogo to participate in a race against local riders and then go hunting. Géminiani recalled sharing a mosquito-infested room with Coppi. Despite Géminiani's advice to cover himself, Coppi, unaccustomed to the insects, spent the night swatting them. Tragically, both contracted malaria.

Upon their return, Géminiani's temperature soared to 106.88000000000001 °F (41.6 °C). He became delirious, experiencing hallucinations and losing recognition of those around him. He was initially treated for hepatitis, then yellow fever, and finally typhoid. The priest at Chamalières reportedly administered the last rites, and his obituary was even circulated to newspapers. He was eventually diagnosed by the Institut Pasteur with Plasmodium falciparum, the most severe form of malaria. While Géminiani recovered, Coppi died, as his doctors mistakenly treated him for a bronchial complaint. Géminiani, who had ridden for Coppi in the Bianchi team in 1953, often spoke of Coppi as "my master," stating that "he taught me everything" and "invented everything: diet, training, technique, he was 15 years ahead of everyone." Géminiani frequently reflected on Coppi's legacy, stating that not a day passed without him thinking of Coppi.

A tangible symbol of their friendship was the Bianchi bicycle (model 231560) that Coppi rode to win the 1950 Paris-Roubaix. Two years later, Coppi gifted this bike to Géminiani, his new teammate. The bike's provenance is well-documented, making it a rare and certain artifact from Coppi's career. It was restored in the early 1990s and returned to Géminiani in November 1995 in a ceremony attended by Gino Bartali. In 2002, Géminiani donated the bicycle to the Vel' d'Auvergne club, where he served as president, and it was later auctioned to raise funds for training young riders.

5.2. Rivalries and Collaborations

Géminiani's career was marked by complex relationships with other prominent figures in cycling, oscillating between intense rivalry and strategic cooperation.

His relationship with Louison Bobet was particularly dynamic. While Géminiani was considered stronger in longer events, Bobet excelled in one-day races. Their clashes were legendary, such as the 1953 Tour de France incident where Géminiani famously emptied his plate on Bobet's head during a team dinner. However, despite their volatile temperaments, their relationship evolved. After a heated exchange with Jean Robic in the 1952 Tour, Géminiani and Bobet, prompted by their soigneur, began to collaborate. Géminiani became a crucial guide for Bobet, "tele-commanding his victories and drawing up his battle plans," and was by Bobet's side during his three Tour de France triumphs. Yet, their rivalry resurfaced in the 1958 Tour de France, where Géminiani, feeling betrayed by the French national team's lack of support against Charly Gaul, publicly accused Bobet and others of being "Judas."

Géminiani also had a notable, albeit brief, physical altercation with Jean Robic during the 1952 Tour, holding him underwater in a bath after Robic made disparaging remarks.

His managerial career saw him navigate the intense rivalry between his protégé, Jacques Anquetil, and the popular Raymond Poulidor. Géminiani was a fierce defender of Anquetil, who, despite his numerous victories, often received less public affection than Poulidor. In 1965, Géminiani orchestrated Anquetil's famous Dauphiné-Bordeaux-Paris double as a direct challenge to Poulidor's perceived popularity, aiming to unequivocally establish Anquetil's athletic superiority.

6. Views and Opinions

Raphaël Géminiani was known for his outspoken and often critical perspectives on various aspects of professional cycling, reflecting a deep passion for the sport and a traditionalist viewpoint.

6.1. Stance on Doping

Géminiani was remarkably candid about doping in cycling, particularly regarding his own generation. In 1962, he stated that he preferred the term "stimulants" to "doping," arguing that it was "normal that a rider takes stimulants" and that "doctors who recommend them." He believed that certain products, far from being dangerous, could "re-establish the body's equilibrium." Géminiani openly admitted to using stimulants during his 12 Tours de France and numerous other races, always "with the guidance of a doctor, naturally." He asserted that "All the riders of my generation doped themselves." In 1977, he controversially labeled doping checks the "cancer of cycling."

Following the tragic death of Tom Simpson during the 1967 Tour de France, where drugs were found in Simpson's body and jersey pockets, Géminiani criticized the Tour de France doctor, Pierre Dumas. Géminiani contended that Dumas was responsible for Simpson's death, arguing that Simpson died of a heart attack and that Dumas's actions-laying Simpson on rocks with his head raised, using an oxygen mask, and helicoptering him to hospital instead of immobilizing him and administering adrenaline-were incorrect. Géminiani's view was contradicted by Dumas's successor, Dr. Miserez, who acknowledged Simpson died of a heart attack but attributed its irreversibility to doping products.

6.2. Critique of Modern Cycling

Géminiani was a vocal critic of contemporary professional cycling, lamenting what he perceived as a decline in its spirit and integrity. He strongly advocated for the return of national teams in the Tour de France, a format used from 1930 to the early 1960s and again in 1967 and 1968. He argued that riders in national jerseys would face greater public and media scrutiny if caught doping, unlike those in commercial team jerseys who could simply change teams six months later. He believed that sponsors would not lose from this change, as they could back riders across multiple national teams, thereby increasing the commercial benefits and media impact of the race. He cited the example of the media attention given to the French women's handball team, which garnered three times more TV spectators than a mountain stage of the Tour de France.

He also criticized the motivations of modern riders, suggesting that many participated with the sole ambition of appearing on television. He famously remarked that they "would be better off taking part in Star Academy!" (a French TV show for aspiring entertainers). He recounted hearing riders in the peloton boast about fulfilling their contracts by getting 10 minutes of TV time with a sports reporter, lamenting that this was "not the Tour de France!" For Géminiani, fulfilling a contract meant "to ride across a col in the Pyrenees at least once alone and at the head of the race. It's to attack on Mont Ventoux as though your life depended on it."

7. Bicycle Brand "R. Géminiani"

Following the tradition of other prominent cyclists, Raphaël Géminiani licensed his name for a range of bicycles, effectively becoming a sponsor for his own teams. There is some uncertainty regarding the manufacturers of these frames, with both Mercier and Cizeron, a company based in Saint-Étienne, being cited as possibilities. It is plausible that both companies produced frames under his brand.

Bicycle mechanic Sheldon Brown described "R. Géminiani" bikes as a significant part of the "French glory years." While many models were considered "unexciting," high-end examples from the early 1960s, particularly those featuring "French component exotica" and in good condition, could be quite valuable. Pedestrian models, however, were generally worth only a few hundred dollars. Brown noted that French bikes from the 1950s and 1960s are complex to understand and price due to their varied quality and components.

8. Major Career Achievements Summary

Raphaël Géminiani's extensive career as a professional cyclist yielded numerous victories and high placings:

- 1943**

- National Junior Road Championships

- 1946**

- 1st Ambert

- 1949**

- 1st Circuit des villes d'eaux d'Auvergne

- 1st Tour de Corrèze

- 1st Stage 19 Tour de France

- 1950**

- 1st GP de Marmignolles

- 1st Polymultipliée

- 4th Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stages 17 & 19

- 1951**

- 1st Overall Grand Prix du Midi Libre

- 1st Polymultipliée

- 2nd Overall Tour de France

- Mountains classification

- 1st Stage 9

- 1952**

- Tour de France

- 1st Stages 8 & 17

- 9th Overall Giro d'Italia

- Mountains classification

- Tour de France

- 1953**

- Road race, National Road Championships

- 9th Overall Tour de France

- 1955**

- 3rd Overall Vuelta a España

- 4th Overall Giro d'Italia

- 6th Overall Tour de France

- 1st Stage 9

- 1956**

- 1st Abidjan

- 1st Bol d'Or des Monédières Chaumeil

- 1957**

- 1st Bol d'Or des Monédières Chaumeil

- 1st Quilan

- 1st Tulle

- 5th Overall Giro d'Italia

- Mountains classification

- 5th Overall Vuelta a España

- 1958**

- 1st Bol d'Or des Monédières Chaumeil

- 1st Thiviers

- 1st Tulle

- 3rd Overall Tour de France

- 8th Overall Giro d'Italia

- 1959**

- 1st GP d'Alger

- Vuelta a España

- 1st Stages 1a (TTT) & 13 (TTT)

9. Death

Raphaël Géminiani died on the morning of 5 July 2024, at the age of 99. He passed away in a hospital in Pont-du-Château, near his hometown of Clermont-Ferrand, and his death was also reported in Pérignat-sur-Allier. His passing marked the end of a long and impactful career in the world of cycling.

10. Legacy and Evaluation

Raphaël Géminiani's legacy in cycling is multifaceted, defined by his accomplishments as both a formidable rider and a pioneering manager, all underpinned by his distinctive and unyielding personality. Remembered as Le Grand FusilThe Big Gun or Top GunFrench, he embodied a fiercely competitive spirit on the bike and an equally passionate, often confrontational, approach off it.

As a rider, his consistent top finishes in all three Grand Tours, including podiums in the Tour de France and Vuelta a España, and his multiple mountains classification titles, cemented his status as one of the strongest French cyclists of his generation. His willingness to attack and his resilience in challenging conditions earned him respect, even from rivals.

His transition to a directeur sportif marked a new era of influence. Géminiani was instrumental in the careers of legends like Jacques Anquetil, guiding him to numerous Grand Tour victories and fiercely defending him against public criticism. His innovative approach to sponsorship, pushing for commercial teams in a sport resistant to change, helped shape modern professional cycling. Despite controversies, his strategic acumen and unwavering support for his riders were undeniable.

Géminiani remained an outspoken voice throughout his life, offering candid, sometimes provocative, opinions on doping, the commercialization of cycling, and the changing motivations of riders. His critiques often reflected a deep nostalgia for a more traditional, perhaps purer, form of the sport, emphasizing courage and genuine competition over media exposure. His strong personality, dedication, and enduring presence made him a beloved and memorable figure, ensuring his place as a significant character in cycling history.