1. Early Life and Background

Philip Francis Rizzuto's journey into baseball began in the bustling streets of Brooklyn, New York, where his family instilled values that shaped his remarkable career.

1.1. Birth and Childhood

Philip Francis Rizzuto was born on September 25, 1917, in Brooklyn, New York City, New York. He was the son of a streetcar motorman and his wife, both of whom were originally from Calabria, Italy. His birth name was originally Fiero. There has been some confusion surrounding his birth year, with early reports sometimes listing 1918, a discrepancy Rizzuto himself reportedly encouraged early in his professional career on the advice of teammates. Later reference sources revised the year to 1917, confirming his age at the time of his death as 89. Official records from the New York City Department of Health also confirm his birth certificate is dated 1917. Rizzuto spent his childhood in Glendale, Queens. Despite his modest stature, typically listed as 5 in and around 150 lb (150 lb) to 160 lb (160 lb) (though he rarely reached the lower figure), he showed early athletic promise. His nickname, "the Scooter," was reportedly given to him by a minor league teammate, Billy Hitchcock, who observed Rizzuto's distinctive running style on the bases.

1.2. Education and Early Career Development

Rizzuto attended Richmond Hill High School in Queens, where he excelled in both baseball and American football. In 1935, while still in high school, he had a tryout with his favorite team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, but was rejected due to his small size, a detail he often recalled and was noted on his baseball cards. Despite this initial setback, Rizzuto's talent was recognized, and he signed with the New York Yankees as an amateur free agent in 1937, marking the beginning of his professional baseball career within the Yankees organization.

2. Playing Career

Philip Francis Rizzuto spent his entire 13-year Major League Baseball playing career as the shortstop for the New York Yankees, becoming a cornerstone of their dynasty and a beloved figure in the sport.

2.1. Major League Debut and Early Success

After an impressive minor league stint, where he received The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year Award in 1940 while playing with the Kansas City Blues, Rizzuto made his Major League debut on April 14, 1941. He quickly took over the starting shortstop position from the popular Frank Crosetti, whose batting average had declined, and immediately established himself as a vital part of the Yankees' lineup. Rizzuto's defensive prowess quickly made him a fan favorite, and he formed an outstanding middle infield combination with second baseman Joe Gordon. Grantland Rice, a prominent syndicated columnist, praised the duo, favorably comparing them to the Brooklyn Dodgers' middle infield of Billy Herman and Pee Wee Reese. Rizzuto's rookie season culminated in a World Series victory over the Dodgers. Although his batting was modest in that series, he played a crucial role in the team's success. In the 1942 World Series, Rizzuto showcased his offensive capabilities, leading all hitters with a .381 batting average and 8 hits, including a home run, despite hitting only four during the regular season.

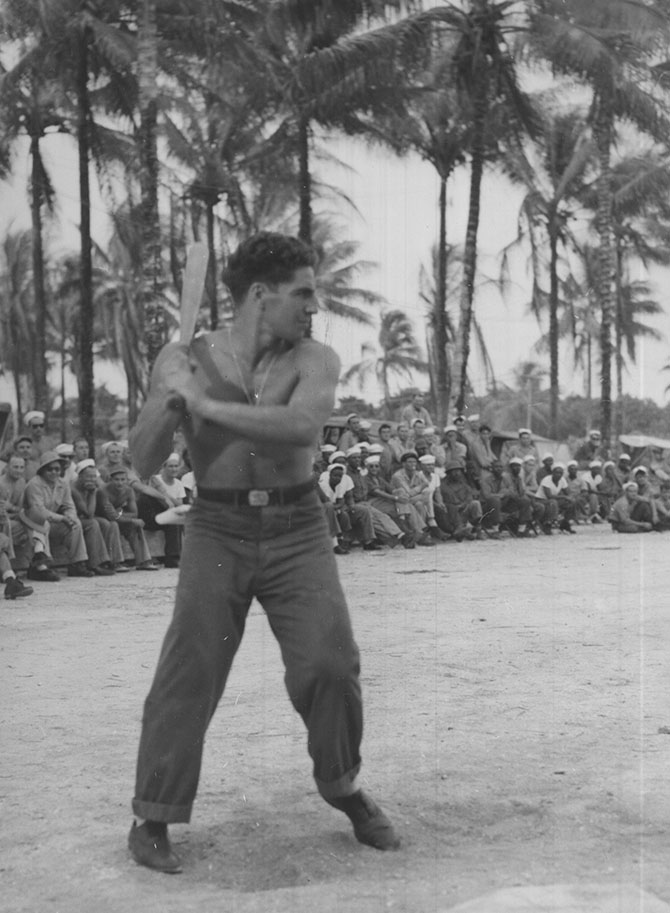

2.2. Military Service during World War II

Like many talented baseball players of his era, Rizzuto's burgeoning career was interrupted by military service during World War II. From 1943 through 1945, he served in the United States Navy. During this period, he continued to play baseball as part of a Navy team, where he reunited with Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese; their team was managed by Yankees catcher Bill Dickey. His service years were a significant interruption to his prime playing years, a factor later considered in discussions about his Hall of Fame induction.

2.3. Peak Performance and Achievements

Upon his return to the Yankees for the 1946 season, Rizzuto encountered Larry MacPhail, the new Yankees general manager. MacPhail, a volatile and innovative executive, became entangled in a dispute with the Mexican League and its owner, Jorge Pasquel, who was recruiting Major League players. Rizzuto himself was rumored to be considering a substantial contract offer from the Mexican League. The situation escalated to lawsuits, with MacPhail even attempting a restraining order against sportswriter Rud Rennie, whom he suspected of encouraging players to defect. This contentious period, perhaps partially due to the off-field distractions, saw Rizzuto's batting average dip in 1946, and the Yankees finished third. However, by 1947, the situation resolved, and Rizzuto's value to the team became increasingly evident. He set a new team record for shortstops with a .969 fielding percentage in 1947, surpassing Frank Crosetti's 1939 mark, and further improved it to .973 in 1948.

Rizzuto's absolute peak as a player occurred in 1949-1950, when he was moved into the leadoff spot in the batting order. In 1950, his MVP season, he hit .324 with 200 hits and 92 walks, scoring 125 runs. Defensively, he led the league in fielding percentage and set a single-season record for shortstops by handling 238 consecutive chances without an error. From September 18, 1949, through June 7, 1950, he played 58 error-free games at shortstop, breaking the AL record of 46 set by Eddie Joost. This record stood for 22 years until Ed Brinkman surpassed it in 1972. In 1950, Rizzuto also recorded 123 double plays, a Yankees franchise record that still stands. His .9817 fielding percentage that year led the league and was less than a point shy of Lou Boudreau's AL record, holding as a Yankees franchise record until 1976 when Fred Stanley posted .983.

Rizzuto was voted the American League's Most Valuable Player by a wide margin in 1950, having been the runner-up to Ted Williams in 1949. Notably, he remains the only MVP in history to have led the league in sacrifice bunts. He was selected to five All-Star Games (1942, and every year from 1950 to 1953). In 1950, he also won the Hickok Belt, awarded to the top professional athlete of the year, and was named Major League Player of the Year by The Sporting News, which also voted him the top major league shortstop for four consecutive years (1949-1952).

In the 1951 World Series, Rizzuto batted .320, earning him the Babe Ruth Award from the New York chapter of the BBWAA as the Series' top player. Decades later, he still expressed resentment over an incident in that series where pugnacious Giants second baseman Eddie Stanky kicked the ball out of his glove on a tag play. Legendary player Ty Cobb praised Rizzuto, naming him and Stan Musial as "two of the few modern ball players who could hold their own among old timers." Even his former tryout manager, Casey Stengel, who had infamously told Rizzuto to "go get a shoeshine box" in 1935, ended up managing Rizzuto through five consecutive championship seasons with the Yankees and later declared, "He is the greatest shortstop I have ever seen in my entire baseball career." Yankees pitcher Vic Raschi famously stated, "My best pitch is anything the batter grounds, lines or pops in the direction of Rizzuto." Long after his retirement, teammate Joe DiMaggio captured Rizzuto's enduring appeal to fans: "People loved watching me play baseball. Scooter, they just loved."

Rizzuto was particularly noted for his "small ball" contributions, which included strong defense and clutch hitting, essential to the Yankees' seven World Series titles. He was regarded as one of the best bunters of his era, leading the AL in sacrifice hits every season from 1949 to 1952. In retirement, he often tutored players on bunting during spring training and would discuss the nuances of different bunt types during his broadcasts, lamenting the decline of bunting as an art in baseball. He also ranked among the AL's top five players in stolen bases seven times. Defensively, Rizzuto led the league three times each in double plays and total chances per game, twice each in fielding and putouts, and once in assists. He holds numerous World Series records for shortstops, including the most career games played, singles, walks, times on base, stolen bases, at-bats, putouts, assists, and double plays. Notably, in the three World Series that went to Game Seven (1947, 1952, 1955), Rizzuto batted an impressive .455.

One of his most legendary plays, as recounted in The New York Times obituary, occurred on September 17, 1951. With the Yankees and Cleveland Indians tied for first place with only 12 games left, Rizzuto was at bat in the bottom of the ninth inning, score tied 1-1, with DiMaggio on third. After arguing a called strike, Rizzuto subtly gave the signal for a squeeze play. DiMaggio broke early, startling Rizzuto. Indians pitcher Bob Lemon, seeing the play unfold, threw high to avoid a bunt, aiming behind Rizzuto. However, with DiMaggio charging, Rizzuto instinctively got his bat up and laid down a bunt. "If I didn't bunt, the pitch would've hit me right in the head," Rizzuto recalled. "I bunted it with both feet off the ground, but I got it off toward first base." DiMaggio scored the winning run, and Stengel hailed it as "the greatest play I ever saw." Lemon, frustrated, threw both the ball and his glove into the stands.

2.4. Later Career and Retirement from Playing

Rizzuto's performance began to decline after 1953, with his batting average dropping to .195 in 1954. His playing time decreased significantly, from 155 games in 1950 to 81 in 1955 and just 31 in 1956. He was officially released by the Yankees on August 25, 1956. Rizzuto frequently recounted the unusual circumstances of his release. Late in the 1956 season, the Yankees re-acquired Enos Slaughter, and Rizzuto was asked to meet with the front office to discuss postseason roster adjustments. He was then asked to suggest players who might be cut to make room for Slaughter. As Rizzuto named players, a reason was given for why each needed to be kept. Finally, Rizzuto realized that the expendable name was his own. He consulted his former teammate George Stirnweiss, who advised him not to "blast" the Yankees, as it might jeopardize future non-playing opportunities. Rizzuto often stated that following Stirnweiss's advice was likely the best decision he ever made.

Upon his retirement, Rizzuto's 1,217 career double plays ranked second in major league history, trailing only Luke Appling's 1,424. His .968 career fielding average was second among AL shortstops, only behind Lou Boudreau's .973. He also ranked fifth in AL history in games played at shortstop (1,647), eighth in putouts (3,219) and total chances (8,148), and ninth in assists (4,666). At the time of his last game, he had appeared in the most World Series games ever (52), a record soon surpassed by five of his Yankees teammates. However, Rizzuto still holds numerous World Series records for shortstops, including career games played, singles, walks, times on base, stolen bases, at-bats, putouts, assists, and double plays.

3. Broadcasting Career

After his illustrious playing career, Philip Francis Rizzuto embarked on a long and influential second act as a radio and television sports announcer for the New York Yankees, becoming a beloved voice for generations of fans.

3.1. Transition to Broadcasting

Following his release by the Yankees in 1956, Rizzuto had several offers to continue playing, including a Major League contract from the St. Louis Cardinals and a minor league offer from the Los Angeles Dodgers. However, he opted to pursue a career in broadcasting. He had received positive reviews when he filled in for the New York Giants' wraparound host Frankie Frisch in September 1956 after Frisch suffered a heart attack. Rizzuto submitted an audition tape to the Baltimore Orioles. Recognizing his potential and popularity, the Yankees' sponsor, Ballantine Beer, insisted that the team hire Rizzuto as an announcer for the 1957 season. This forced General Manager George Weiss to dismiss Jim Woods, who had only been with the Yankees for four years. Weiss reportedly told Woods it was the first time he had to fire someone without a reason.

3.2. Broadcast Style and Memorable Moments

Rizzuto broadcast Yankee games on radio and television for an remarkable 40 years. His popular catchphrase "Holy cow!" became instantly recognizable, along with "Unbelievable!" or "Did you see that?" to describe great plays. He would also affectionately call someone a "huckleberry" if he disapproved of their actions. Rizzuto's broadcasting style was highly idiosyncratic and conversational. He frequently broke from traditional play-by-play to wish listeners happy birthdays or anniversaries, send get-well wishes to fans in hospitals, praise restaurants he liked, or comment on the cannoli he ate between innings. This tendency for off-topic chatter sometimes led him to coin the unique scoring notation "WW" for his scorecard, meaning "Wasn't Watching."

He often joked about leaving games early, saying to his wife, "I'll be home soon, Cora!" and "I gotta get over that bridge," referring to the often-congested George Washington Bridge he used to commute back to his home in Hillside, New Jersey. In later years, Rizzuto would announce only the first six innings of Yankee games; occasionally, the TV director would humorously show a shot of the bridge (visible from the top of Yankee Stadium) after his departure. Rizzuto was also known for his severe fear of lightning and would sometimes leave the booth following violent thunderclaps.

Rizzuto began his broadcasting career working alongside legendary announcers Mel Allen and Red Barber in 1957. Over the course of his career, he formed memorable partnerships, most notably with Frank Messer (1968-1985) and Bill White (1971-1988). This trio, Rizzuto, Messer, and White, presided over a significant era for the Yankees, spanning the non-winning CBS years through championship seasons and the tumultuous Steinbrenner era. Their television broadcast team remained unchanged from 1972 to 1982. Rizzuto was assigned to broadcast two World Series for NBC-TV: the 1964 World Series with Joe Garagiola Sr. and the 1976 World Series with Garagiola and Tony Kubek. The 1976 series was notable as the last to feature a local announcer from each participating team as a guest. He typically referred to his broadcast partners by their last names, a habit he also maintained with teammates during his playing days. Rizzuto earned a reputation as a "homer," sometimes openly rooting for the Yankees. In 1978, upon hearing the news of Pope Paul VI's death after a Yankee win, he famously remarked, "Well, that kind of puts the damper on even a Yankee win," a comment Esquire magazine dubbed the "Holiest Cow of 1978."

Rizzuto's most iconic broadcasting moments included his call of Roger Maris's new single-season home run record on October 1, 1961, which he delivered on WCBS radio:

"Here's the windup, fastball, hit deep to right, this could be it! Way back there! Holy cow, he did it! Sixty-one for Maris! And look at the fight for that ball out there! Holy cow, what a shot! Another standing ovation for Maris, and they're still fighting for that ball out there, climbing over each other's backs. One of the greatest sights I've ever seen here at Yankee Stadium!"

He also famously called the pennant-winning home run hit by Chris Chambliss in the 1976 American League Championship Series on October 14, 1976, on WPIX-TV:

"He hits one deep to right-center! That ball is out of here! The Yankees win the pennant! Holy cow, Chris Chambliss on one swing! And the Yankees win the American League pennant. Unbelievable, what a finish! As dramatic a finish as you'd ever want to see! With all that delay, we told you Mark Littell had to be a little upset. And holy cow, Chambliss hits one over the fence, he is being mobbed by the fans, and this field will never be the same, but the Yankees have won it in the bottom of the 9th, 7 to 6!"

Rizzuto was also on the microphone for the 1978 American League East tie-breaker game that decided the dramatic 1978 AL East race between the Yankees and the Boston Red Sox, the Pine Tar Incident involving George Brett in 1983, and Phil Niekro's 300th career win in 1985.

3.3. Final Years in Broadcasting

On August 15, 1995, the evening of former teammate Mickey Mantle's funeral, Rizzuto was scheduled to broadcast a road game against the Boston Red Sox. His announcing partner, Bobby Murcer, had already left to attend the funeral. Rizzuto, however, was not initially permitted to leave, as the team needed him for color commentary. After five innings, Rizzuto abruptly left the booth, stating he could not continue. He announced his retirement from announcing soon after, a decision attributed to this incident. He was eventually persuaded to return for one more season in 1996, during which he called the first career home run of another Yankees shortstop protégé, Derek Jeter. Rizzuto retired for good at the end of that season. Apart from his military service, he had spent the first 60 years of his adult life within the Yankee organization, first as a minor league player (1937-1940), then a major league player (1941-1942, 1946-1956), and finally as a broadcaster (1957-1996). Although Mel Allen is widely known as the "Voice of the Yankees," Rizzuto holds the distinction of being the longest-serving broadcaster in Yankees history, with 40 years compared to Allen's 30 years across two stints.

4. Personal Life and Other Activities

Beyond the baseball diamond and broadcast booth, Philip Francis Rizzuto's personal life was marked by a strong family foundation, significant charitable contributions, and a few notable forays into popular culture.

4.1. Family Life

Rizzuto married Cora Anne Ellenborn on June 23, 1943. They had first met the previous year when Rizzuto filled in for Joe DiMaggio as a speaker at a communion breakfast in Newark. Rizzuto famously recalled falling "in love so hard I didn't go home," renting a nearby hotel room for a month to be near her. The Rizzutos moved to Hillside, New Jersey, in 1949, initially residing in an apartment in Monroe Gardens. With later financial successes, they moved to a Tudor home on Westminster Avenue, where they lived for many years. Philip and Cora had four children: daughters Cindy, Patricia, and Penny, and a son, Phil Jr.

Rizzuto was known for his intense fear of snakes. Opposing players, aware of this, would sometimes play practical jokes on him by placing rubber snakes in his baseball glove. Whenever this occurred, Rizzuto refused to approach his glove until he was assured the snake was artificial.

4.2. Charity Work and Public Appearances

Rizzuto dedicated significant time and effort to charitable endeavors, particularly supporting St. Joseph's School for the Blind in Jersey City, New Jersey. He first met Ed Lucas, a young boy who had lost his sight after being struck by a baseball, at a charity event in New Jersey in 1951. Rizzuto developed a keen interest in Lucas and his school. Until his death, Rizzuto tirelessly raised millions of dollars for St. Joseph's by donating profits from his commercials and books, and by hosting the Annual Phil Rizzuto Celebrity Golf Classic and "Scooter" Awards. Rizzuto and Lucas maintained a close friendship, and it was through Rizzuto's influence that Lucas's 2006 wedding was the only one ever conducted at Yankee Stadium. Lucas was one of Rizzuto's last visitors at his nursing home, just days before his passing.

Beyond baseball, Rizzuto made various television appearances, including on Goodson-Todman Productions game show What's My Line? (as the first mystery guest in 1950, and later as a guest panelist and mystery guest), CBS's The Ed Sullivan Show, To Tell The Truth, and The Phil Silvers Show. Alongside his Yankees broadcasts, Rizzuto hosted It's Sports Time with Phil Rizzuto, a five-minute weekday evening sports show on the CBS Radio Network from 1957 to 1977. He also served as the longtime celebrity spokesman in TV advertisements for The Money Store for nearly 20 years, from the 1970s into the 1990s.

In a unique collaboration, Rizzuto provided play-by-play commentary during the extended spoken bridge in Meat Loaf's 1977 song "Paradise by the Dashboard Light." Ostensibly an account of a baseball sequence, the commentary famously (and metaphorically) describes a man's efforts to engage in coitus. When Rizzuto recorded his contribution, he was reportedly unaware of the song's suggestive context. He later recalled his parish priest calling him in shock once the song became popular. However, Meat Loaf stated, "Phil was no dummy. He knew exactly what was going on, and he told me such. He was just getting some heat from a priest and felt like he had to do something." Rizzuto would later jokingly retell the story, claiming he was "snookered" by Meat Loaf but maintaining a good attitude about it. He was flattered when Meat Loaf asked him to tour but declined, quipping that Cora would "kill him." Rizzuto was awarded a gold record for the album.

5. Honors and Legacy

Philip Francis Rizzuto received numerous accolades and recognitions throughout and after his life, cementing his enduring influence on baseball and the New York Yankees.

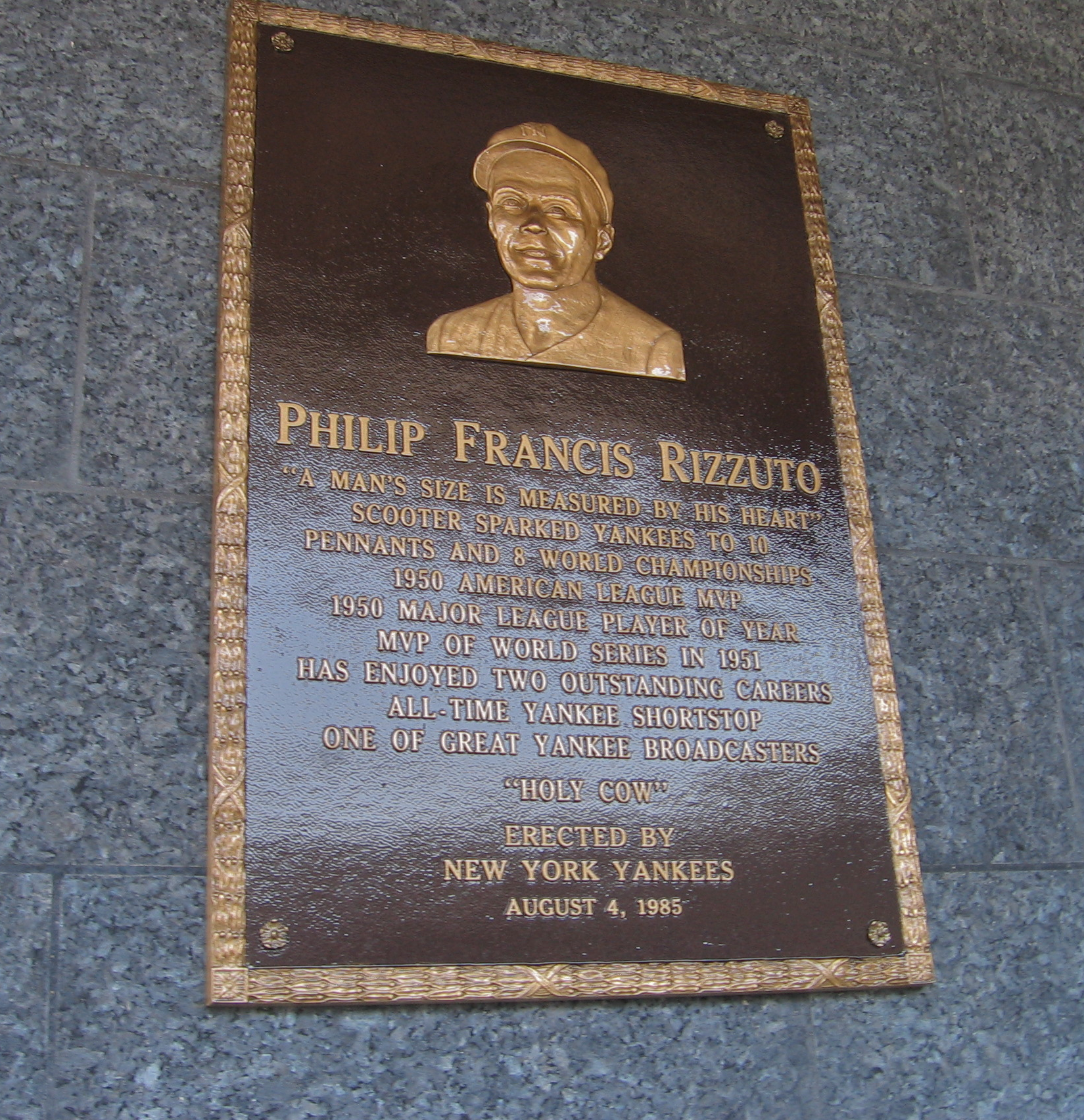

5.1. Number Retirement and Stadium Tributes

The New York Yankees officially retired Rizzuto's uniform number 10 in a ceremony at Yankee Stadium on August 4, 1985. During the same ceremony, a commemorative plaque honoring him was dedicated and placed in the stadium's Monument Park. The plaque acknowledges that he "has enjoyed two outstanding careers, all-time Yankee shortstop, one of the great Yankee broadcasters." A memorable moment from the ceremony occurred when Rizzuto was accidentally bumped to the ground by a live cow wearing a halo, symbolizing his famous "holy cow!" catchphrase; both Rizzuto and the cow were unhurt. He later described the encounter humorously: "That big thing stepped right on my shoe and pushed me backwards, like a karate move." Coincidentally, on the same day, future broadcast partner Tom Seaver recorded his 300th career victory.

Most baseball observers, including Rizzuto himself, came to believe that Derek Jeter had surpassed him as the greatest shortstop in Yankees history. Rizzuto paid tribute to his heir apparent during the 2001 postseason at Yankee Stadium, playfully imitating Jeter's celebrated game-saving backhand throw to home plate, which had just occurred during the Yankees' 2001 American League Division Series triumph. A photograph of Jeter and Rizzuto taken that evening is reportedly one of Jeter's most cherished possessions.

5.2. Baseball Hall of Fame Induction

Despite his impressive career, Rizzuto's election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame was a long and arduous process. In spring 1957, following Rizzuto's release from the Yankees, Baltimore Orioles manager Paul Richards asserted, "Among those shortstops whom I have had the good fortune to see in action, it's got to be Rizzuto on top for career achievement." Sportswriter Dan Daniel also believed Rizzuto would eventually be elected to the Hall of Fame. However, it would take over 35 years for this assessment to come to fruition.

Rizzuto was finally elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1994, alongside Leo Durocher (who was selected posthumously). His induction followed a lengthy and passionate campaign by Yankee fans, who had become frustrated by his continued exclusion. Many of Rizzuto's peers, including Boston Red Sox legend Ted Williams, supported his candidacy. Williams famously claimed that his Red Sox team would have won most of the Yankees' 1940s and 1950s pennants if they had had Rizzuto at shortstop. However, Rizzuto remained characteristically modest about his achievements, stating, "My stats don't shout. They kind of whisper." The push for his induction intensified, particularly after 1984, when the Veterans Committee elected Pee Wee Reese, the similarly regarded shortstop of the crosstown Brooklyn Dodgers, who also had a long broadcasting career and was comparable in stature and impact.

Baseball statistician Bill James extensively discussed Rizzuto's long candidacy in his book Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?, analyzing his career statistics and comparing him to other players. While James noted that Rizzuto's career statistics were statistically below typical Hall of Fame standards, he acknowledged the impact of the years missed due to World War II. Despite calling Rizzuto a great defensive player and a good hitter, James initially did not endorse his candidacy due to the existence of many similar players with comparable accomplishments. However, James's book later noted Rizzuto's election in 1994 and, in 2001, he ranked Rizzuto as the 16th greatest shortstop of all time, placing him ahead of eight other Hall of Fame shortstops. Rizzuto himself consistently expressed humility about the honor, saying, "I never thought I deserved to be in the Hall of Fame. The Hall of Fame is for the big guys, pitchers with 100 mph fastballs and hitters who sock homers and drive in a lot of runs. That's the way it always has been, and the way it should be."

His induction speech in Cooperstown was famously meandering and discombobulated, characterized by his repeated complaints about buzzing flies. The New York Times columnist Ira Berkow humorously mimicked Rizzuto's "inimitable and wondrous digressions and ramblings," including a moment where Rizzuto asked his former broadcast partner, Bill White, what a certain food that "looks like oatmeal" was called, to which White replied, "Grits."

5.3. Other Recognition and Influence

In 1999, the minor league Staten Island Yankees named their mascot "Scooter the Holy Cow" in Rizzuto's honor. He was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2009. A park in Elizabeth, New Jersey, directly across from Kean University, is also named after him. In 2013, the Bob Feller Act of Valor Award recognized Rizzuto as one of 37 Baseball Hall of Fame members for his service in the United States Navy during World War II.

6. Death

Philip Francis Rizzuto's final years saw a decline in his health, leading to his passing in 2007, an event that deeply resonated with the New York Yankees and the wider baseball community.

6.1. Health Decline

Concerns about Rizzuto's health began to surface when he did not attend the annual Cooperstown reunion in 2005 and the annual New York Yankees Old Timers Day in 2006. His last public appearance was in early 2006, where he appeared visibly frail and announced that he was putting much of his memorabilia on the market for charity. In September 2006, his 1950 MVP plaque fetched 175.00 K USD, three of his World Series rings sold for 84.83 K USD, and a Yankee cap with chewing gum on it sold for 8.19 K USD. The majority of these proceeds went to St. Joseph's School for the Blind in Jersey City, his longtime charity of choice. In September 2006, the New York Post reported that Rizzuto was in a "private rehab facility, trying to overcome muscle atrophy and problems with his esophagus." In his last extensive interview, on WFAN radio in late 2005, Rizzuto revealed he had undergone an operation where much of his stomach was removed and was being treated with medical steroids, a topic he lightly joked about in light of baseball's performance-enhancing drugs scandal.

6.2. Passing and Commemoration

Philip Francis Rizzuto died in his sleep on August 13, 2007, from pneumonia. He passed away three days shy of the 51st anniversary of his last game as a Yankee, exactly twelve years after the death of his former teammate Mickey Mantle, and just over a month before his 90th birthday. He had been in declining health for several years and had been living at a nursing home in West Orange, New Jersey, during the final months of his life. At the time of his death, at age 89, Rizzuto was the oldest living member of the Baseball Hall of Fame. He was survived by his wife, Cora (who died in 2010), their daughters Cindy, Patricia, and Penny, their son Phil Jr., and two granddaughters. The day after his passing, the Yankees paid tribute to Rizzuto during their game against the Baltimore Orioles by flying the flag at half-mast at Yankee Stadium. For the remainder of the season, the Yankees wore a black armband with his number 10 on their uniforms as a sign of mourning and respect.

7. Awards and Achievements

Philip Francis Rizzuto accumulated numerous awards and set several significant records during his playing career with the New York Yankees.

Major Awards and Honors:

- American League Most Valuable Player: 1950

- Babe Ruth Award (World Series top player): 1951

- Major League Baseball All-Star: 1942, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953

- Hickok Belt (Top Professional Athlete of the Year): 1950

- The Sporting News Major League Player of the Year: 1950

- The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year: 1940

- The Sporting News Top Major League Shortstop: 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952

- New York Yankees Retired Number: No. 10 (1985)

- National Baseball Hall of Fame Inductee: 1994

- New Jersey Hall of Fame Inductee: 2009

- Bob Feller Act of Valor Award: 2013

Career Batting Statistics:

| Year | Age | Team | League | Games | Plate Appearances | At-Bats | Runs | Hits | Doubles | Triples | Home Runs | RBI | Stolen Bases | Walks | Strikeouts | Batting Average | On-Base Percentage | Slugging Percentage | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 23 | NYY | AL | 133 | 548 | 515 | 65 | 158 | 20 | 9 | 3 | 46 | 14 | 27 | 36 | 0.307 | 0.343 | 0.398 | 0.741 |

| 1942 | 24 | NYY | AL | 144 | 613 | 553 | 79 | 157 | 24 | 7 | 4 | 68 | 22 | 44 | 40 | 0.284 | 0.343 | 0.374 | 0.718 |

| 1946 | 28 | NYY | AL | 126 | 518 | 471 | 53 | 121 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 38 | 14 | 34 | 39 | 0.257 | 0.315 | 0.310 | 0.625 |

| 1947 | 29 | NYY | AL | 153 | 623 | 549 | 78 | 150 | 26 | 9 | 2 | 60 | 11 | 57 | 31 | 0.273 | 0.350 | 0.364 | 0.714 |

| 1948 | 30 | NYY | AL | 128 | 539 | 464 | 65 | 117 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 50 | 6 | 60 | 24 | 0.252 | 0.340 | 0.328 | 0.668 |

| 1949 | 31 | NYY | AL | 153 | 712 | 614 | 110 | 169 | 22 | 7 | 5 | 65 | 18 | 72 | 34 | 0.275 | 0.352 | 0.358 | 0.711 |

| 1950 | 32 | NYY | AL | 155 | 735 | 617 | 125 | 200 | 36 | 7 | 7 | 66 | 12 | 92 | 39 | 0.324 | 0.418 | 0.439 | 0.857 |

| 1951 | 33 | NYY | AL | 144 | 629 | 540 | 87 | 148 | 21 | 6 | 2 | 43 | 18 | 58 | 27 | 0.274 | 0.350 | 0.346 | 0.696 |

| 1952 | 34 | NYY | AL | 152 | 673 | 578 | 89 | 147 | 24 | 10 | 2 | 43 | 17 | 67 | 42 | 0.254 | 0.337 | 0.341 | 0.678 |

| 1953 | 35 | NYY | AL | 134 | 506 | 413 | 54 | 112 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 54 | 4 | 71 | 39 | 0.271 | 0.383 | 0.351 | 0.734 |

| 1954 | 36 | NYY | AL | 127 | 369 | 307 | 47 | 60 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 3 | 41 | 23 | 0.195 | 0.291 | 0.251 | 0.541 |

| 1955 | 37 | NYY | AL | 81 | 181 | 143 | 19 | 37 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 7 | 22 | 18 | 0.259 | 0.369 | 0.322 | 0.691 |

| 1956 | 38 | NYY | AL | 31 | 65 | 52 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 0.231 | 0.310 | 0.231 | 0.541 |

| Career Totals (13 seasons) | 1,661 | 6,711 | 5,816 | 877 | 1,588 | 239 | 62 | 38 | 563 | 149 | 651 | 398 | 0.273 | 0.351 | 0.355 | 0.706 | |||