1. Early Life and College Career

Lou Boudreau's formative years involved a diverse family background and exceptional athleticism, particularly in basketball, which he pursued extensively before committing to professional baseball.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Boudreau was born on July 17, 1917, in Harvey, Illinois, to Birdie (Henry) and Louis Boudreau. His father was of French-Canadian descent, while his mother was Jewish. Both of his maternal grandparents were observant Orthodox Jews, and Boudreau fondly recalled celebrating Passover seders with them in his youth. Following his parents' divorce, he was raised in the Catholic faith by his father.

1.2. High School and Collegiate Sports

Boudreau attended Thornton Township High School in Harvey, Illinois, where he was a standout basketball player. He led his high school team, the "Flying Clouds," to three consecutive Illinois state championship games, winning titles in 1933 and finishing as runner-up in both 1934 and 1935.

He continued his athletic prowess at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he was a member of the Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity. Boudreau became a captain for both the basketball and baseball teams. In the 1936-37 academic year, he played a pivotal role in leading both the Fighting Illini basketball and baseball teams to Big Ten Conference championships. His exceptional talent in basketball earned him NCAA Men's Basketball All-American honors during the 1937-38 season.

While still enrolled at Illinois, Boudreau signed an agreement with Cleveland Indians general manager Cy Slapnicka, receiving an undisclosed sum in exchange for his commitment to play baseball for the Indians after graduation. This professional agreement, however, led to his being ruled ineligible for collegiate sports by Big Ten Conference officials. During his senior year at Illinois, he also played professional basketball for the Hammond Ciesar All-Americans in the National Basketball League. Despite commencing his professional baseball career with Cleveland, Boudreau successfully completed his education, earning a Bachelor of Science in education from the University of Illinois in 1940. He also contributed to his alma mater as the Illinois freshman basketball coach in 1939 and 1940, and later served as an assistant coach for the 1941-42 Illinois Fighting Illini men's basketball team. In this role, he was instrumental in recruiting Andy Phillip, who would later be inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

2. Professional Baseball Career

Lou Boudreau's professional baseball career was marked by his exceptional abilities as both a player and an innovative manager, leading his teams to significant achievements, most notably a World Series championship with the Cleveland Indians.

2.1. Player-Manager with the Cleveland Indians (1938-1950)

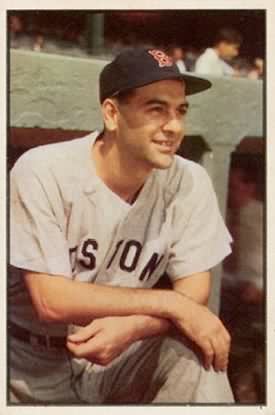

Boudreau made his Major League Baseball debut as a third baseman for the Cleveland Indians on September 9, 1938, at the age of 21. In 1939, Indian manager Ossie Vitt informed Boudreau that he would need to transition from his natural third base position to shortstop, as established slugger Ken Keltner already held the starting third base job.

In 1940, his first full season as a starter, Boudreau batted .295, hitting 46 doubles and recording 101 RBI. His performance earned him an All-Star Game selection, the first of seven consecutive seasons he would be named an All-Star (though the 1945 All-Star Game was cancelled due to wartime travel restrictions).

Boudreau was part of a historic moment in 1941 when he played a crucial role in ending Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak. In the eighth inning of a game against the New York Yankees on July 17, after two outstanding stops by Keltner at third base on hard-hit ground balls earlier in the game, Boudreau barehanded a difficult bad-hop grounder to short and initiated a double play, retiring DiMaggio at first base. Despite a modest .257 batting average that season, he led the American League with 45 doubles.

Following the 1941 season, Indians owner Alva Bradley promoted manager Roger Peckinpaugh to general manager and appointed the 25-year-old Boudreau as player-manager. This made him the youngest player-manager in MLB history. Boudreau continued to play and manage the Indians throughout World War II. His eligibility for military service was classified as 4-F due to arthritis in his ankles, a condition aggravated by his basketball career. In 1944, Boudreau set an MLB record for a player-manager by turning 134 double plays. That same year, he won the American League batting title with an average of .327.

When Bill Veeck purchased the Indians in 1947, he renewed Boudreau's player-manager agreement. Despite initial mixed feelings on both sides - Boudreau even suggesting he'd prefer to be traded than only play shortstop - public support for Boudreau was overwhelming. In 1948, Boudreau delivered a phenomenal season, hitting .355 with 18 home runs and 106 RBI. He was a central figure in the Cleveland offense, demonstrating consistent hitting and clutch performance, rarely striking out more than 57 times in a season. Boudreau's exceptional defensive skills and ability to turn double plays solidified his reputation as one of the best shortstops of his era, earning him eight defensive awards over his 15-year career. Although not a significant base-stealing threat (only 87 successful steals out of 158 attempts in his career), his aggressive play on hits led him to lead the league in doubles three times in the 1940s.

The Indians clinched the American League pennant in a dramatic one-game playoff against the Boston Red Sox, with Boudreau hitting two home run in the decisive game. They then went on to defeat the Boston Braves in the 1948 World Series in six games, securing the franchise's first World Series championship in 28 years and only the second in their history. Both Veeck and Boudreau publicly acknowledged each other's vital roles in the team's success. As player-manager, Boudreau was also known for his innovative approach, notably converting former third baseman Bob Lemon into a pitcher, a move that proved highly successful as Lemon became a 20-game winner in 1948 and later a Hall of Famer. Boudreau's relentless playing style and consistent integrity earned him the respect of his teammates; for instance, in a crucial 1940 game against the Yankees, he came off the bench to deliver a game-winning hit and also supported manager Ossie Vitt when some players sought his dismissal.

2.2. Boston Red Sox and Kansas City Athletics (1951-1957)

Following the 1950 season, Boudreau was released by the Indians as both a player and manager. He then signed with the Boston Red Sox, where he played full-time in 1951. He assumed the role of player-manager for the Red Sox in 1952, eventually transitioning to managing exclusively from the bench for the 1953 and 1954 seasons. After his tenure with Boston, Boudreau became the inaugural manager for the Kansas City Athletics in 1955, following their relocation from Philadelphia. He managed the Athletics for 104 games before being fired in 1957 and replaced by Harry Craft.

2.3. Chicago Cubs (1960)

Boudreau's final managerial stint was with the Chicago Cubs during the 1960 season. After this, he officially retired from managing professional baseball teams.

2.4. Managerial Record

Lou Boudreau's overall managerial record spanned 16 seasons, accumulating 1,162 wins and 1,224 losses, resulting in a winning percentage of .487. His crowning achievement as a manager was leading the Cleveland Indians to the 1948 World Series championship. Beyond this single title, his teams achieved only two third-place finishes. However, Boudreau is highly regarded for his ability to develop talent, most notably converting Bob Lemon from a third baseman to a successful pitcher who later earned Hall of Fame induction.

| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| CLE | 1942 | 154 | 75 | 79 | .487 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1943 | 153 | 82 | 71 | .536 | 3rd in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1944 | 154 | 72 | 82 | .468 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1945 | 145 | 73 | 72 | .503 | 5th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1946 | 154 | 68 | 86 | .442 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1947 | 154 | 80 | 74 | .519 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1948 | 155 | 97 | 58 | .626 | 1st in AL | 4 | 2 | .667 | Won World Series (BSN) |

| CLE | 1949 | 154 | 89 | 65 | .578 | 3rd in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE | 1950 | 154 | 92 | 62 | .597 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| CLE total | 1377 | 728 | 649 | .529 | 4 | 2 | .667 | |||

| BOS | 1952 | 154 | 76 | 78 | .494 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BOS | 1953 | 153 | 84 | 69 | .549 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BOS | 1954 | 154 | 69 | 85 | .448 | 4th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| BOS total | 461 | 229 | 232 | .497 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| KC | 1955 | 154 | 61 | 93 | .396 | 6th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| KC | 1956 | 154 | 52 | 102 | .338 | 8th in AL | - | - | - | - |

| KC | 1957 | 103 | 36 | 67 | .350 | fired | - | - | - | - |

| KC total | 411 | 151 | 260 | .367 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| CHC | 1960 | 137 | 54 | 83 | .394 | 7th in NL | - | - | - | - |

| CHC total | 137 | 54 | 83 | .394 | 0 | 0 | - | |||

| Total | 2386 | 1162 | 1224 | .487 | 4 | 2 | .667 | |||

3. Boudreau Shift

Lou Boudreau is widely recognized for inventing the defensive strategy known as the "Boudreau shift," a tactic that significantly influenced baseball strategy. The shift was famously deployed on July 14, 1946, during the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox, specifically targeting the formidable left-handed slugger Ted Williams. Williams had hit three home runs in the first game, prompting Boudreau, who was serving as player-manager for the Cleveland Indians, to devise a countermeasure.

Against Williams, a pronounced pull hitter, Boudreau strategically moved most of his Cleveland Indian fielders to the right of second base. This left only the third baseman and left fielder positioned to the left of second base, but even they were stationed unusually close to second base and far to the right of their conventional positions. This radical alignment aimed to anticipate Williams's typical hard-pulled hits.

Despite the obvious tactical advantage presented by the empty left side of the field, Williams, known for his stubborn pride, famously refused to follow the advice of his teammates to hit or bunt towards left field. While the shift did not drastically diminish his hitting prowess, Boudreau later revealed in his autobiography, Player-Manager, that the primary intention behind the shift was more psychological than tactical. He stated, "I always considered the Boudreau shift a psychological, rather than a tactical" ploy, aiming to get inside Williams's head rather than purely to defend against his hits. The Boudreau Shift proved to be influential, inspiring similar strategies like the "王シフトŌ ShiftJapanese" used in Japanese baseball against slugger Sadaharu Oh. Williams occasionally attempted to bunt or hit to the unoccupied left side, but he was reportedly booed by fans, leading him to revert to his preferred pull-hitting approach.

4. Broadcasting Career

After concluding his managerial career, Lou Boudreau embarked on a long and successful career as a radio announcer. He began doing play-by-play for Chicago Cubs games in 1958-59. In 1960, he briefly returned to managing the Cubs, swapping roles with "Jolly Cholly" Charlie Grimm. However, after just one season as the Cubs' manager, Boudreau returned to the radio booth and remained a fixture there until 1987.

In addition to his baseball commentary, Boudreau expanded his broadcasting roles to other sports. He provided radio play-by-play for the Chicago Bulls from 1966 to 1968 and also worked on Chicago Blackhawks games for WGN radio and television.

Boudreau's deep understanding of baseball rules proved invaluable during his broadcasting career. A notable incident occurred on June 23, 1976, during the second game of a doubleheader between the Cubs and the Pittsburgh Pirates at Wrigley Field. The Cubs were trailing by two runs in the fourth inning when the umpires called the game due to darkness (Wrigley Field did not have lights until 1988) and announced that it would be resumed the following day at the exact point of stoppage, as was standard procedure for suspended games at the time. However, Boudreau recognized that the game had not yet progressed to five innings (or four and a half with the home team leading), which meant it had not become an "official game." According to the rules, an unofficial game could not be suspended and had to be replayed entirely from the first pitch (the rule for rain-outs at that time). Boudreau quickly went to the clubhouse and explained the rule to the umpires. After consulting the National League office, the umpires confirmed Boudreau's interpretation, resulting in the game being replayed from the start and effectively nullifying the Cubs' two-run deficit.

5. Later Life, Honors, and Legacy

Lou Boudreau's later life was filled with significant recognition and tributes, solidifying his enduring legacy as one of baseball's most respected figures.

5.1. National Baseball Hall of Fame Induction

In honor of his remarkable career and contributions to the sport, Lou Boudreau was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1970. He garnered 77.33% of the vote on his tenth ballot, recognizing his impact as both a player and manager.

5.2. Retired Number and Other Tributes

In the same year as his Hall of Fame induction, 1970, his uniform number 5 was officially retired by the Cleveland Indians. While he wore number 5 with the Indians, he notably wore number 4 during his tenure with the Boston Red Sox. His legacy is further cemented by geographical tributes; in 1973, the city of Cleveland renamed a street adjacent to Cleveland Municipal Stadium in his honor. Additionally, Boudreau Drive in Urbana, Illinois, where he attended college, is also named after him.

In 1990, the Cleveland Indians established The Lou Boudreau Award, which is presented annually to the organization's Minor League Player of the Year, recognizing outstanding young talent within their system. In 1992, his number 5 jersey was also retired by the Illinois Fighting Illini baseball program, a rare honor. Boudreau is one of only three Illinois Fighting Illini athletes to have their number retired across all sports, joining football legends Red Grange and Dick Butkus, underscoring his exceptional status in the university's athletic history.

6. Personal Life and Death

Lou Boudreau's personal life revolved around his family, and he maintained a residence in Illinois for many years until his passing.

6.1. Family

In 1938, Boudreau married Della DeRuiter, and their marriage produced four children. Their daughter, Sharyn, later married Denny McLain, a former star pitcher for the Detroit Tigers. McLain notably achieved the rare feat of winning 30 games in a single major league season (31-6) for the 1968 World Series champion Detroit Tigers, making him the last pitcher to reach that milestone.

6.2. Death

Lou Boudreau resided in Frankfort, Illinois, for many years. He died on August 10, 2001, at the age of 84, due to cardiac arrest at St. James Medical Center in Olympia Fields, Illinois. His funeral was held according to Catholic rites, and he was interred in the Pleasant Hill Cemetery.