1. Life and Background

Osman Batur's early life in the Altai region significantly shaped his path as a military leader and a figure of resistance.

1.1. Birth and Childhood

Osman Batur was born in 1899 with the birth name Osman Islamuly (also translated as Osman Islam). His birthplace was Öngdirkara, located in the Köktogay region of Altay, which is present-day Koktokay County, Altay Prefecture, Xinjiang, China. He was the son of Islam Bey, a middle-class farmer from the nomadic Kazakh community. The honorific "Batur," meaning "hero" or "brave," was later bestowed upon him by his allies, reflecting his leadership and courage.

1.2. Education and Early Activities

Accounts of Osman Batur's childhood suggest he was considered a skilled rider and a master hunter even before the age of 10. He reportedly received martial arts training from Böke Batur, a Kazakh leader, at the age of 12. However, some historical sources dispute the exact age of his training, suggesting that these stories may have been embellished to create a more "heroic upbringing" narrative. Böke Batur himself was later captured and beheaded by the Chinese in Tibet while attempting to reach his ancestral homeland in Turkey. By 1940, as the administration of the Republic of China began to increase its military presence and pressure in the Altai region, Osman Batur retreated to the mountains, taking up arms to begin his solitary struggle against the encroaching forces. This marked the beginning of his long and persistent fight for Kazakh autonomy.

2. Major Activities and Achievements

Osman Batur's leadership was central to numerous conflicts and movements aimed at securing the independence and autonomy of the Kazakh people in the Altai region.

2.1. Resistance Against China and the Soviet Union

Beginning in 1941, Osman Batur launched a full-scale struggle against both Chinese and Soviet forces, driven by the objective of liberating all Altai lands and East Turkestan from their control. During World War II, as both China and the Soviet Union were preoccupied with the invading Axis powers, Turkic independence movements in the region gained significant momentum. This geopolitical context provided a crucial opportunity for Osman Batur's rise. By 1943, he successfully achieved his initial goal of expelling all Chinese forces from Altai. On July 22, 1943, in a ceremony held in Bulgun, Osman Batur officially declared the Altai Khanate, a symbolic act of Kazakh self-determination. His fighting force, which numbered around 30,000 people at its peak, gradually diminished to approximately 4,000 by 1950 due to continuous conflict and attrition. The struggle also involved internal dynamics, including conflicts between Osman Batur and figures like Alibek Hakim and his comrades.

2.2. Role in the East Turkestan Republic

Osman Batur's relationship with the Second East Turkestan Republic (ETR) was complex and often contentious. In the 1930s, he was a relatively unknown gang leader, but by 1940, he emerged as one of the key leaders of the Kazakh uprising in the Altai district against Governor General Sheng Shicai. This rebellion was sparked by the authorities' decision to transfer traditional Kazakh pastures and watering places to settled peasants, primarily Dungans and Chinese. In 1943, the Altai Kazakhs rebelled again when authorities decided to relocate them to southern Xinjiang to make way for Chinese refugees on their nomadic lands.

After meeting with Khorloogiin Choibalsan, the leader of the Mongolian People's Republic (MPR), Osman Batur's rebels received weapons from the MPR. In the spring of 1944, he was forced to retreat to Mongolia, with his unit's departure covered by the air forces of both the MPR and the Soviet Union. In the fall of 1945, Osman Batur's detachment liberated the Altai District from the Kuomintang. Following this victory, the ETR government appointed Osman Batur as the Governor of the Altai District.

However, disputes between Osman Batur and the ETR government arose almost immediately. The Altai governor frequently refused to comply with the instructions of the republic's leadership, and his troops often acted independently, disobeying the army's command. For instance, when the ETR army suspended military operations against Kuomintang troops to engage in negotiations for a single coalition government in Xinjiang, Osman Batur's detachments not only ignored this directive but intensified their activities. His gangs were also known to smash and plunder Kuomintang units and villages controlled by the ETR. This behavior led Joseph Stalin to famously label Osman Batur as "a social bandit." In 1946, citing illness, Osman Batur resigned from his post as governor and reverted to his independent role as a "field commander," continuing to raid settlements within the ETR.

2.3. Relations with the Kuomintang and Other Powers

Osman Batur's strategic alliances shifted throughout his career, reflecting the volatile geopolitical landscape of Xinjiang. At the end of 1946, he formally sided with the Kuomintang authorities, receiving the post of a specially authorized representative of the Xinjiang government in the Altai District. This alliance positioned him as one of the most dangerous adversaries of both the ETR and the Mongolian People's Republic (MPR).

In early June 1947, a detachment led by Osman Batur, consisting of several hundred fighters and supported by Kuomintang army units, invaded the territory of Mongolia in the Baitag-Bogd region. Osman Batur's forces destroyed a border outpost and penetrated deep into MPR territory. On June 5, Mongolian troops, supported by Soviet aviation, successfully repelled the invaders. Subsequently, the Mongols launched a counter-invasion into Xinjiang but were defeated in the area of the Chinese outpost of Betashan. Both sides continued to exchange several raids and skirmishes until the summer of 1948. The Baitag-Bogd incident led to a diplomatic exchange of notes between Beijing and Moscow, with both sides issuing mutual accusations and protests.

Osman Batur continued to support the Kuomintang government, receiving reinforcements in terms of personnel, weapons, and ammunition. In the fall of 1947, he engaged in further battles with ETR troops in the Altai District and even managed to temporarily capture the capital of Shara-Sume County. The ETR authorities were forced to carry out additional mobilization efforts to counter his advances. However, Osman Batur was eventually defeated and compelled to flee eastward.

2.4. Pursuit of Altai Autonomy and Independence

A central and consistent theme throughout Osman Batur's activities was his unwavering pursuit of Kazakh self-determination and the establishment of an autonomous or independent Altai. His declaration of the Altai Khanate in Bulgun on July 22, 1943, was a powerful expression of this ambition. He harbored long-term plans to create an Altai Khanate that would be entirely independent of both the ETR and China. In this endeavor, he hoped for support from Mongolia, a prospect that caused considerable concern in Moscow. The head of the NKVD, Lavrentiy Beria, even approached Vyacheslav Molotov with a request to coordinate actions against this "Kazakh Robin Hood" with Marshal Choibalsan of the MPR. Despite attempts by the ETR army command, Soviet representatives, and Choibalsan himself to reason with the rebellious commander, Osman Batur remained committed to his vision of an independent Altai, often acting outside the established political frameworks.

3. Ideology and National Aspirations

Osman Batur's actions were deeply rooted in his commitment to Kazakh national identity and the aspiration for self-determination.

3.1. Kazakh National Identity and Self-determination

Osman Batur's core beliefs centered on the liberation and autonomy of the Kazakh people in the Altai region. His initial struggle, beginning in 1941, aimed to expel both Chinese and Russian influences from all Altai lands and East Turkestan. He saw the increasing military presence and administrative decisions of the Chinese government, such as the transfer of traditional Kazakh pastures and the forced relocation of nomadic communities, as direct threats to the Kazakh way of life and national identity. His declaration of the Altai Khanate in 1943 was a direct manifestation of his ideological commitment to Kazakh self-rule, reflecting a strong desire for an independent state free from external domination. He viewed the broader Turkic independence movements during World War II as an opportunity to realize these aspirations, solidifying his role as a champion for Kazakh national rights and freedom.

4. Personal Life

Beyond his military and political endeavors, Osman Batur's personal life was marked by profound tragedy amidst the turbulent conflicts he navigated.

4.1. Family Circumstances

Osman Batur's family endured immense suffering as a consequence of his protracted struggle. Following his capture and the Communist takeover of Xinjiang, his children were apprehended by Chinese forces. They were subjected to torture and subsequently killed. The tragic fate of her children led his wife to lose her sanity, and in a state of despair, she reportedly threw herself into a swiftly flowing river, where she drowned. These personal losses underscore the devastating human cost of the conflicts in which Osman Batur was embroiled.

5. Death

Osman Batur's long struggle for Kazakh autonomy concluded with his capture and execution, marking a decisive moment in the region's history.

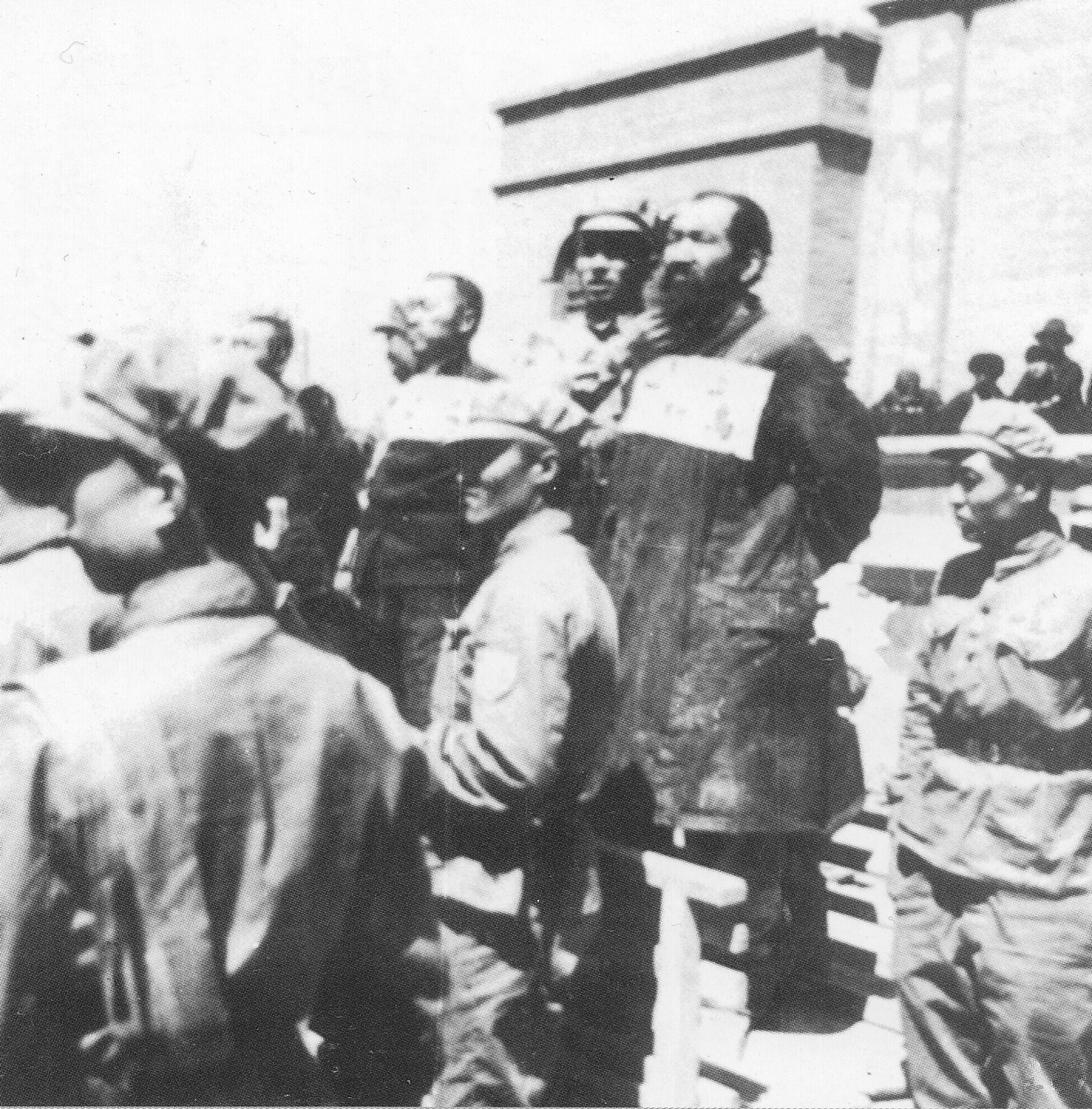

5.1. Capture and Execution

In 1949, the Kuomintang government in China was defeated, and the Communists successfully occupied Xinjiang. Osman Batur, true to his rebellious spirit, immediately rose in revolt against the new Communist government. His resistance, however, was ultimately suppressed. He was captured in Hami, located in Eastern Xinjiang. Following his apprehension, he was brought to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang. There, he was publicly displayed, or "circulated," before being executed on April 29, 1951. His death marked the end of a significant chapter in the Kazakh struggle for independence in the Altai region.

6. Evaluation and Legacy

Osman Batur's historical significance is complex, encompassing both his heroic contributions to Kazakh self-determination and the criticisms leveled against his methods and alliances.

6.1. Positive Contributions

Osman Batur is widely regarded as a powerful symbol of resistance for the Kazakh people. His relentless efforts to expel Chinese and Soviet forces from the Altai region and his declaration of the Altai Khanate underscore his commitment to protecting Kazakh autonomy and their traditional nomadic way of life. He mobilized his fellow Kazakhs against external domination, providing a rallying point for those who sought self-determination. His struggle, though ultimately unsuccessful in achieving full independence, instilled a sense of national identity and resilience among the Kazakh community, particularly in Xinjiang. For many, he remains a heroic figure who bravely fought for his people's freedom against overwhelming odds.

6.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Despite his heroic image, Osman Batur's actions also drew criticism and controversy. Joseph Stalin famously labeled him a "social bandit," a term that highlighted his propensity for independent action, his refusal to fully submit to the authority of the East Turkestan Republic, and reports of his forces engaging in plundering activities against both Kuomintang units and ETR-controlled villages. Furthermore, some historical accounts suggest that stories of his early life, such as his martial arts training at a very young age, may have been embellished to create a more "heroic upbringing" narrative. These criticisms point to the complex nature of his leadership, which, while driven by national aspirations, sometimes involved methods that were disruptive or opportunistic within the broader political landscape.

7. Impact on the Kazakh Community

Osman Batur's life and ultimate fate had a profound and lasting impact on the Kazakh people, particularly those residing in Xinjiang.

7.1. The Kazakh Exodus from Xinjiang

Following Osman Batur's execution in 1951, many of his devoted followers and their families faced severe repression from the new Communist government. This led to a significant and arduous migration, known as the Kazakh exodus from Xinjiang. Thousands of Kazakhs, fearing persecution, embarked on a perilous journey over the Himalayas to seek refuge. This mass movement of people, driven by the desire to escape political and cultural oppression, eventually led to their resettlement in Turkey. The Turkish government facilitated their relocation, providing a new home for these displaced communities. This exodus not only marked a tragic chapter in Kazakh history but also contributed significantly to the formation of the Kazakh diaspora, with a substantial community establishing itself in Turkey, preserving their cultural heritage and the memory of their struggle for freedom.