1. Overview

Naram-Sin (𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪Narām-SînAkkadian or Naram-Suen), a name meaning "Beloved of the Moon God Sin", reigned as ruler of the Akkadian Empire from approximately circa 2254 to circa 2218 BC. He was the third successor and grandson of Sargon of Akkad, the empire's founder. Under Naram-Sin's rule, the Akkadian Empire reached its maximum territorial extent, becoming the largest Mesopotamian empire to date. He was an exceptionally powerful military leader, renowned for crushing widespread revolts and significantly expanding the empire into regions stretching from the Zagros Mountains to Turkey and Iran, and extending to the Mediterranean Sea coast.

Naram-Sin was also the first Mesopotamian king to claim divinity for himself, adopting the unprecedented title "God of Akkad." He further asserted universal sovereignty by being the first to claim the title "King of the Four Quarters" or "King of the Universe." His reign was marked by significant administrative reforms aimed at strengthening direct royal control over the vast and diverse empire. Despite his remarkable military and political successes, later Mesopotamian historiography, particularly the myth of "The Curse of Akkad," often associated his actions with the empire's eventual decline, portraying him as a figure who angered the gods. His enduring fame and powerful legacy led later rulers, such as Naram-Sin of Eshnunna and Naram-Sin of Assyria, to adopt his name, reflecting his lasting impact on ancient Mesopotamian kingship.

2. Biography

Naram-Sin's personal life is rooted deeply within the Akkadian Empire's ruling dynasty, connecting him directly to its founder, Sargon of Akkad, and extending to influential family members who held significant religious and administrative roles.

2.1. Early Life and Family

Naram-Sin was the son of Manishtushu, who was the second successor to Sargon of Akkad. This lineage made Naram-Sin the nephew of King Rimush and the grandson of both Sargon and Tashlultum. A prominent figure in his immediate family was his aunt, Enheduanna, who served as the High Priestess, holding a vital religious position within the empire. The exact order of succession among Sargon's descendants has been subject to historical debate; while most versions of the Sumerian King List show Naram-Sin following Manishtushu, the Ur III version of the list reverses the order of Rimush and Manishtushu. Linguistically, Naram-Sin's name, or Naram-Suen, is more accurately reconstructed in Old Akkadian as Naram-Suyin (or /narām-tsuyin/) or Naram-Su'in (/narām-tsu'in/).

2.2. Children

Naram-Sin had several notable children who played active roles within the Akkadian administration and religious hierarchy, demonstrating his strategy of appointing family members to key positions to strengthen central control. His most prominent son was Shar-Kali-Sharri, who succeeded him as king of the Akkadian Empire. Another son, Nabi-Ulmaš, served as the governor of Tutub. Excavations at Tell Mozan (the site of ancient Urkesh) revealed a seal impression belonging to Tar'am-Agade, a daughter of Naram-Sin previously unknown to modern scholarship, who may have been married to an unidentified endan (ruler) of Urkesh. Additionally, a recently discovered cylinder seal from Irisaĝrig indicated that Sharatigubishin, the governor of that city, was also Naram-Sin's son.

Other known children include:

- Enmenana, who was a "zirru priestess of the god Nanna," the "spouse of the god Nanna," and an "entu priestess of the god Sin at Ur."

- Šumšani, an ēntum-priestess of Shamash at Sippar.

- An unnamed son who served as governor at Marad.

- An unnamed daughter who was an ēntum-priestess at Nippur.

- Bin-kali-šarrē.

- Lipit-ilē, also a governor at Marad.

- Rigmuš-ālsu.

- Me-Ulmaš.

- Ukēn-Ulmaš.

- His granddaughter, Lipus-ia-um.

One of Naram-Sin's daughters, Tuṭṭanabšum (also known as Tudanapšum), held the highly important religious position of high priestess of Enlil at Nippur. Uniquely, she was also deified, making her the only female and only non-king known to have been declared a god in this period.

3. Reign and Achievements

During his extensive reign, Naram-Sin undertook significant military campaigns that expanded the Akkadian Empire to its greatest extent, while also implementing crucial administrative and governance reforms to solidify his authority and integrate the vast territories. A pivotal event was a widespread revolt that he brutally suppressed, leading to his unprecedented self-deification.

3.1. Empire Expansion and Integration

Naram-Sin inherited an empire that, according to some theories, had lost significant portions of its conquered territories from Sargon's time. However, he quickly reasserted Akkadian dominance and expanded its borders even further. He successfully defeated Manium, the king of Magan (likely modern-day Oman), and campaigned against various northern hill tribes residing in the Zagros Mountains, Taurus Mountains, and Amanus Mountains, extending his empire all the way to the Mediterranean Sea.

His military prowess is famously depicted on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, which commemorates his triumph over Satuni, the chief of the Lullubi people in the Zagros Mountains. The Sumerian King List notes his reign length as 56 years, and at least 20 of his year-names, used to label each year of his reign, provide further evidence of his extensive military actions. These records mention campaigns against important cities and regions such as Uruk and Subartu. One specific year-name refers to his victory over Simurrum in Kirasheniwe, during which he captured Baba, the governor of Simurrum, and Dubul, the ensi of Arame.

The conquest of Armanum (whose exact location is unknown but proposed as Tall Bazi) and Ebla (located about 34 mile (55 km) southwest of modern Aleppo) was a significant achievement, as Ebla had also been subdued by his grandfather Sargon. Inscriptions on a marble lamp, a stone plaque, and a copper bowl explicitly declare Naram-Sin "the mighty, king of the four quarters, conqueror of Armanum and Ebla." A newly discovered stele fragment (IM 221139) from Tulul al-Baqarat (thought to be ancient Kesh) also describes this campaign. It states that "no king whosoever had destroyed Armanum and Ebla" before Naram-Sin, and that the gods Nergal and Dagan granted him these victories, along with the Amanus, the Cedar Mountain, and the Upper Sea (likely the Mediterranean). His empire also saw trade relations with Meluhha (the Indus Valley Civilisation) and controlled significant parts of the Persian Gulf. He established administrative centers at key locations like Nagar (Tell Brak) and Nineveh, further solidifying Akkadian control.

3.2. Administrative and Governance Reforms

To manage the vast and expanding Akkadian Empire, Naram-Sin implemented significant administrative reforms, moving towards a more centralized and direct royal control over the formerly independent city-states. A key strategy was the appointment of his numerous sons to crucial provincial governorships and his daughters to influential high priestess positions throughout the empire. This ensured loyalty and direct supervision from the royal family.

While many local rulers were replaced, some loyal governors retained their positions. These included Meskigal, who served as the governor of the city-state of Adab, and Karsum, the governor of the unlocated city of Niqqum. Another notable loyalist was Lugal-ushumgal of Lagash. Several inscriptions from Lugal-ushumgal, including seal impressions, refer to him as the governor of Lagash and a "servant" (𒀵aradAkkadian) of Naram-Sin, indicating his vassal status. Lugal-ushumgal continued to serve Naram-Sin's successor, Shar-Kali-Sharri. Naram-Sin also reformed the scribal system, likely to improve record-keeping and communication across his extensive domain. The construction of new fortresses and communication networks was also part of this effort, enabling better military and administrative control over the expanded territories. Year names of Naram-Sin also refer to his construction work on temples in Akkad, Nippur, and Zabala.

3.3. The Great Revolt and Self-Deification

The most pivotal internal event of Naram-Sin's reign was a widespread and formidable revolt that challenged the very foundations of the Akkadian Empire. This empire, largely built by his grandfather Sargon, stretched from Syria (including cities like Tell Brak and Tell Leilan) in the west, across Elam and its associated polities in the east, into southern Anatolia in the north, and encompassing all traditional Sumerian powers in the south, such as Uruk, Ur, and Lagash. Many of these regions had long histories as independent entities and frequently reasserted their autonomy throughout the Akkadian period.

At an unspecified point during his rule, a massive uprising occurred, fueled by a large coalition of city-states. The rebellion was led by Iphur-Kis of Kish and Amar-Girid of Uruk, and they were joined by Enlil-nizu of Nippur. Other participating city-states included Kutha, TiWA, Sippar, Kazallu, Kiritab, Apiak, and Borsippa, along with "Amorite highlanders." This extensive network of rebels forced Naram-Sin to engage in intense military campaigns. Historical records, including several Old Babylonian copies of earlier inscriptions and one contemporary Old Akkadian document, shed light on these events.

A crucial source is the Bassetki Statue, discovered in 1974, which served as the base for a life-sized copper statue of Naram-Sin. Its inscription recounts:

"Naram-Sin, the mighty, king of Agade, when the four quarters together revolted against him, through the love which the goddess Astar showed him, he was victorious in nine battles in one in 1 year, and the kings whom they (the rebels?) had raised (against him), he captured. In view of the fact that he protected the foundations of his city from danger, (the citizens of his city requested from Astar in Eanna, Enlil in Nippur, Dagan in Tuttul, Ninhursag in Kes, Ea in Eridu, Sin in Ur, Samas in Sippar, (and) Nergal in Kutha, that (Naram-Sin) be (made) the god of their city, and they built within Agade a temple (dedicated) to him. As for the one who removes this inscription, may the gods Samas, Astar, Nergal, the bailiff of the king, namely all those gods (mentioned above) tear out his foundations and destroy his progeny."

In the aftermath of successfully quelling this monumental revolt, Naram-Sin took the unprecedented step of deifying himself. He also posthumously deified his grandfather Sargon and his father Manishtushu, though notably not his uncle Rimush. This act marked a significant shift in Mesopotamian kingship, establishing a precedent for divine rulers. The impact and memory of this revolt resonated deeply in later Sumerian literary compositions, which include titles such as "Great Revolt against Naram-Sin," "Naram-Sin and the Enemy Hordes," and "Gula-AN and the Seventeen Kings against Naram-Sin." These texts indicate the lasting historical and cultural significance of this rebellion.

3.4. Control of Elam and Foreign Relations

The region of Elam had been under Akkadian domination since the time of Sargon of Akkad, but it remained a restive territory. Sargon's successor, Rimush, campaigned there, adding "conqueror of Elam and Parahsum" to his royal titles. Manishtushu, the third ruler, further solidified control by conquering the cities of Anshan and Pashime in Elam, where he subsequently installed imperial governors.

Naram-Sin continued this policy of asserting Akkadian authority over Elam. He extended his royal titulary to include "commander of all the land of Elam, as far as Parahsum." Under his rule, Akkadian military governors (known as shakkanakkus), such as Ili-ishmani and Epirmupi, were appointed in Elam, suggesting direct administration by the Akkadian Empire. Naram-Sin also exerted considerable influence over Susa, where he funded the construction of temples and set up inscriptions in his own name. Furthermore, he mandated the use of the Akkadian language in official documents, replacing Elamite.

A unique peace treaty, written in the Old Elamite language using an Old Akkadian script, was signed between Naram-Sin (who is not deified in the treaty text) and an unknown Elamite king, sometimes speculated to be Khita. The treaty's crucial clause stated: "The enemy of Naram-Sin is my enemy, the friend of Naram-Sin is my friend." This formal agreement, which mentions about twenty gods (a mix of Elamite, Sumerian, and Akkadian deities, including Inshushinak, Humban, Nahiti, Simut, and Pinikir), is believed to have been a strategic move by Naram-Sin to secure peace on his eastern borders. This allowed him to more effectively address the growing threat posed by the Gutians from the Zagros Mountains, who would later play a significant role in the downfall of the Akkadian Empire.

3.5. Royal Titles and Symbols

Naram-Sin made profound changes to traditional Mesopotamian kingship by adopting unprecedented royal titles that underscored his elevated status and imperial ambitions. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have explicitly claimed divinity for himself, a radical departure from previous rulers who merely acted as intermediaries between gods and humans. This claim was formalized through his adoption of the title "God of Akkad."

Furthermore, Naram-Sin was the first ruler to claim the expansive title "King of the Four Quarters" or "King of the Four Regions" (𒈗 𒆠𒅁𒊏𒁴 𒅈𒁀𒅎lugal ki-ibratim arbaimAkkadian). This title superseded the earlier "King of the World" (Lugal kiš kiLugal kiš kiAkkadian) used by his predecessors, including Sargon. The new title reflected the significantly expanded territorial reach of his empire, which indeed covered a vast area encompassing what was considered the "four quarters" of the known world at that time.

Following his successful suppression of the Great Revolt, Naram-Sin began to include a divine determinative, the silent honorific "dingir" ({{lang|akk|𒀭|}}) before his name in inscriptions and documents. This symbolic addition further cemented his claim to divinity and influenced subsequent Mesopotamian monarchs, establishing a new paradigm for royal self-perception and authority.

4. Legacy and Historical Assessment

Naram-Sin remains one of the most famous kings of the Akkadian Empire, often mentioned in conjunction with his grandfather, Sargon. His reign marked the empire's territorial peak, but it also became associated, in later Mesopotamian tradition, with the empire's eventual decline. This complex legacy is reflected in various historical and cultural narratives that emerged centuries after his rule.

4.1. The Curse of Akkad Legend

A significant aspect of Naram-Sin's legacy is the Mesopotamian historiographic poem titled "The curse of Akkad: the Ekur avenged." This myth, composed hundreds of years after Naram-Sin's death, serves as a theological explanation for the collapse of the Akkadian Empire and the destruction of its capital, Akkad. The poem posits that Naram-Sin's impious actions brought about divine retribution.

According to the narrative, Naram-Sin angered the chief god Enlil by plundering the Ekur, Enlil's sacred temple in Nippur. In response to this sacrilege, Enlil unleashed the Gutians-a mountain tribe from the hills east of the Tigris River-upon Mesopotamia. Their invasion brought widespread plague, famine, and death. The poem dramatically illustrates the severity of the famine by describing vastly inflated food prices: for example, one lamb could only purchase half a sila (approximately 26 in3 (425 ml)) of grain, half a sila of oil, or half a mina (approximately 8.8 oz (250 g)) of wool.

To avert complete destruction of Sumer, eight other gods-namely Inanna, Enki, Sin, Ninurta, Utu, Adad, Nusku, and Nidaba-intervened. They decreed that only the city of Akkad should be destroyed to spare the rest of Sumer, and subsequently cursed it. The poem concludes with a powerful description of Akkad's desolation, echoing the gods' curse:

"Its chariot roads grew nothing but the 'wailing plant,'

Moreover, on its canalboat towpaths and landings,

No human being walks because of the wild goats, vermin, snakes, and mountain scorpions,

The plains where grew the heart-soothing plants, grew nothing but the 'reed of tears,'

Akkad, instead of its sweet-flowing water, there flowed bitter water,

Who said 'I would dwell in that' found not a good dwelling place,

Who said 'I would lie down in Akkad' found not a good sleeping place.'"

This legend, while not a factual historical account, reflects a later Mesopotamian attempt to rationalize the end of the powerful Akkadian Empire and the subsequent period of Gutian dominance. It portrays Naram-Sin as a figure whose hubris and disregard for traditional religious norms led to catastrophic consequences for his dynasty and people. Historically, the Gutians did invade Akkad after Naram-Sin's death, seizing control of the region by approximately circa 2124 BC and remaining there for about 125 years before being expelled by the Neo-Sumerian Empire.

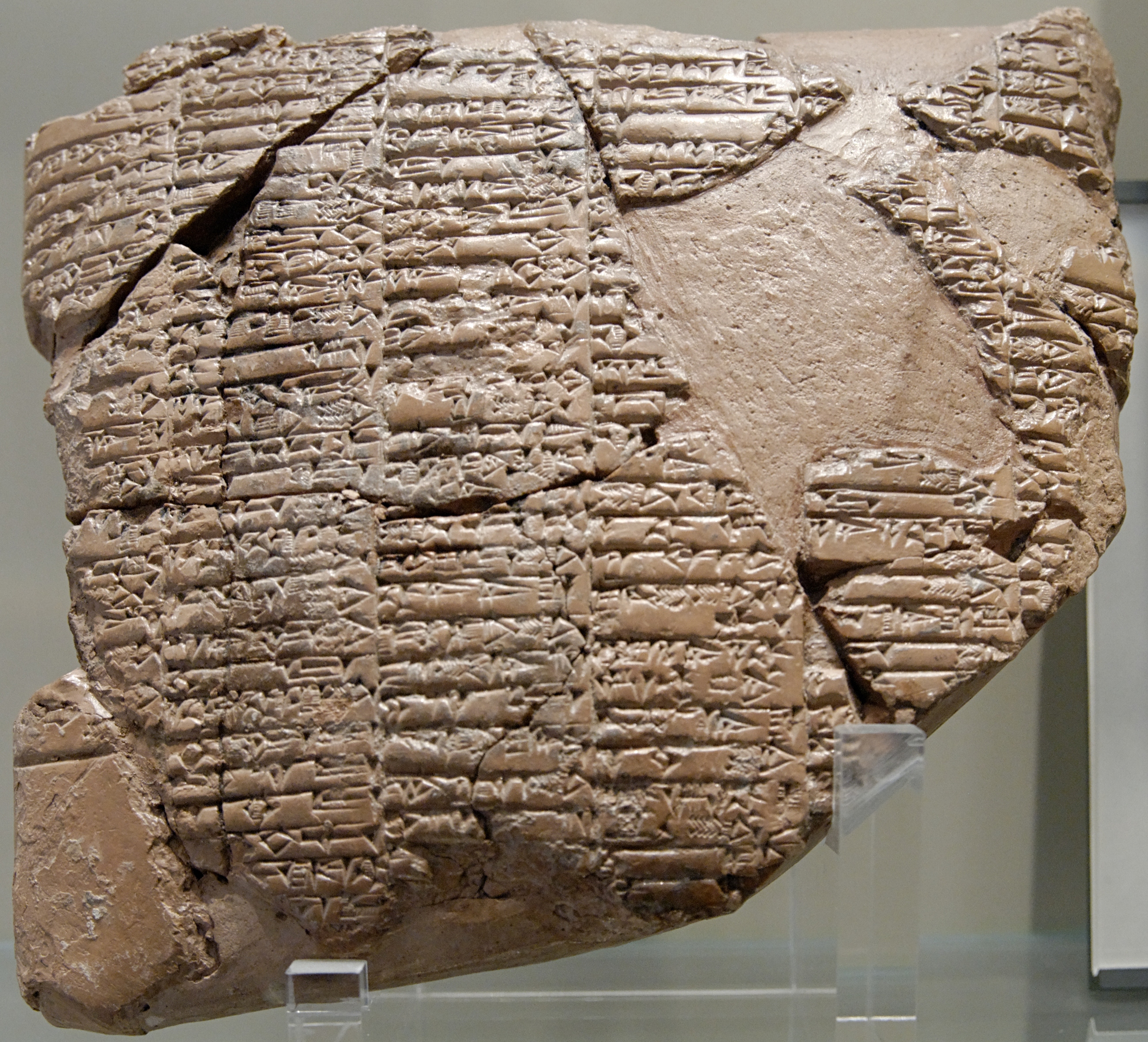

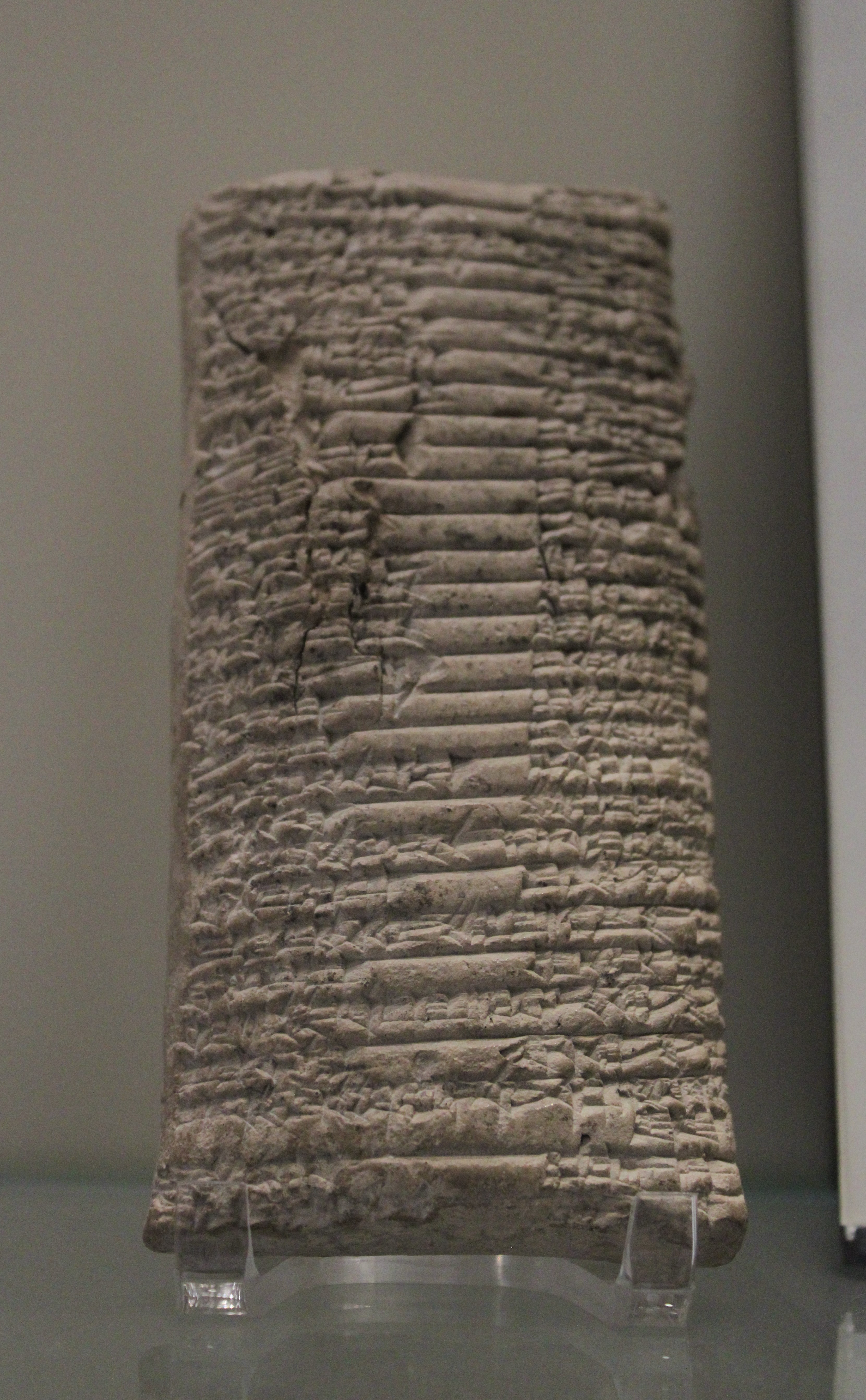

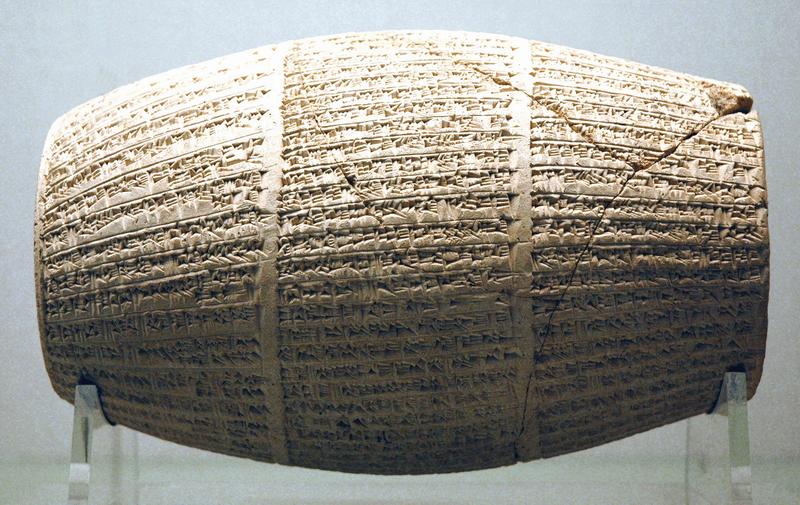

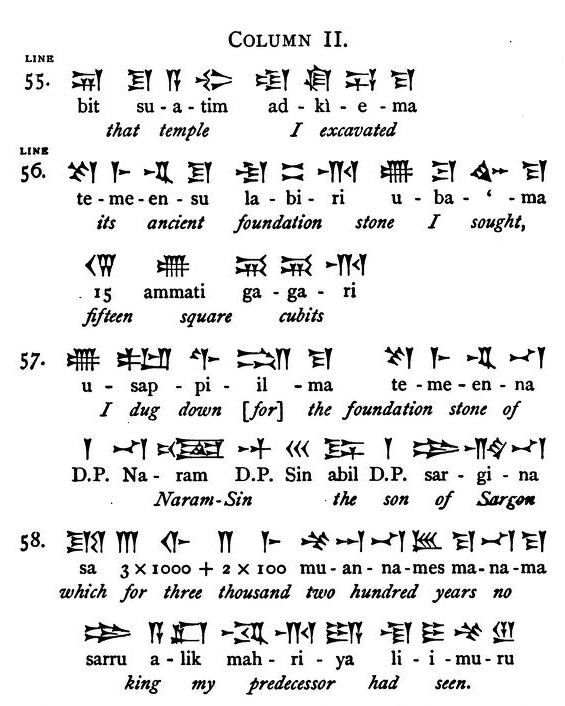

4.2. Nabonidus' Excavations

Centuries after Naram-Sin's reign, in the Neo-Babylonian period, King Nabonidus (who ruled around circa 550 BC) undertook significant archaeological activities related to Naram-Sin. Nabonidus is sometimes characterized as the "first archaeologist" due to his pioneering efforts in excavating and attempting to date ancient artifacts and structures.

He initiated excavations that led to the discovery and analysis of a foundation deposit belonging to Naram-Sin. His work involved unearthing foundation deposits of various temples, including those dedicated to Šamaš, the sun god, and Anunitu, the warrior goddess, both located in Sippar. He also found and restored the sanctuary that Naram-Sin had built for the moon god in Harran. Notably, Nabonidus was also the first known individual to attempt to scientifically date an archaeological artifact, specifically Naram-Sin's temple. Despite his groundbreaking efforts, his estimate of the temple's age was significantly inaccurate, by approximately 1,500 years.

4.3. In Popular Culture

Naram-Sin's historical significance and legendary status have led to his depiction in modern popular culture.

- In the 2021 video game The Dark Pictures Anthology: House of Ashes, Naram-Sin appears as a character. The game's main plot unfolds within his personal temple. In this portrayal, he is the self-proclaimed "God King" of Akkad, engaged in a war with the Gutians after incurring the wrath of the god Enlil for sacking his temple. Naram-Sin's character was voiced and motion-captured by Sami Karim.

- In the 2021 mobile gacha game Blue Archive, the innermost chamber of the large floating quantum supercomputer known as the "Ark of Atra-Hasis" (a reference to the Akkadian myth of the same name) is designated as the "Throne of Naram-Sin."

5. Artifacts

Naram-Sin's reign is well-documented through a variety of significant archaeological artifacts that provide invaluable insights into Akkadian art, royal inscriptions, and material culture. These objects not only commemorate his achievements but also illustrate the artistic and administrative sophistication of the Akkadian Empire.

5.1. Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

Naram-Sin's most renowned and artistically significant monument is the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin. This monument is carved from pinkish limestone, stands 79 in (200 cm) (6 feet 7 inches) tall, and is 41 in (105 cm) wide. It depicts Naram-Sin as a triumphant god-king, symbolized by his distinctive horned helmet, ascending a mountain. Below him, his soldiers are shown, while his defeated enemies, the Lullubi led by their king Satuni, are trampled and impaled, with Satuni imploring Naram-Sin for mercy. Naram-Sin himself is depicted at twice the size of his soldiers, emphasizing his superhuman status.

Artistically, the stele marked a departure from traditional Mesopotamian relief carving by employing successive diagonal tiers to convey the narrative, though some smaller broken fragments suggest that more traditional horizontal registers might have been used elsewhere on the monument. It has also been suggested that the stele contains some of the earliest known depictions of battle standards and plate armor.

The stele was originally located in Sippar but was broken at the top when it was carried away as spoils of war by the Elamite forces of King Shutruk-Nakhunte in the 12th century BC, along with other monuments. It was later discovered by Jacques de Morgan at Susa (modern Iran) and is now a prized possession of the Louvre Museum in Paris (inventory number Sb 4).

The inscription above the king's head, written in the Akkadian language, is highly fragmentary but indicates a dedication related to his victory over the Lullubum highlanders:

"[Nar]am-Sin, the mighty,

Additionally, Shutruk-Nahhunte added his own inscription in Middle Elamite to the stele, stating:

"I am Shutruk-Nahhunte, son of Hallutush-Inshushinak, beloved servant of the god Inshushinak, king of Anshan and Susa, who has enlarged the kingdom, who takes care of the lands of Elam, the lord of the land of Elam. When the god Inshusinak gave me the order, I defeated Sippar. I took the stele of Naram-Sin and carried it off, bringing it to the land of Elam. For Inshushinak, my god, I set it as an offering." This secondary inscription confirms the stele's capture and relocation.

A similar stele fragment (ES 1027), measuring 22 in (57 cm) high by 17 in (42 cm) wide by 7.9 in (20 cm) deep, also depicting Naram-Sin, was discovered in a well at Pir Hüseyin, a few miles northeast of Diarbekr (though this was not its original context). It is believed to have been first found in Miyafarkin, a village about 47 mile (75 km) northeast of Diarbekr.

Fragments of an alabaster stele showing captives being led by Akkadian soldiers are sometimes attributed to Naram-Sin, or possibly Rimush or Manishtushu, based on stylistic similarities. This stele is considered graphically more sophisticated than those of Sargon, Rimush, or Manishtushu. Two fragments (IM 55639 and IM 59205) are housed in the National Museum of Iraq, and one (MFA 66.89) is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These fragments were reportedly excavated in either Wasit (al-Hay district, Wasit Governorate) or Nasiriyah, both in Iraq. It is speculated that this stele might represent the outcome of Naram-Sin's campaigns in Cilicia or Anatolia, a theory supported by the distinctive metal vessel carried by a soldier, which is more characteristic of contemporary Anatolian designs than Mesopotamian ones.

5.2. Other Notable Artifacts

Beyond his famous Victory Stele, numerous other artifacts from Naram-Sin's reign provide further archaeological and historical insights:

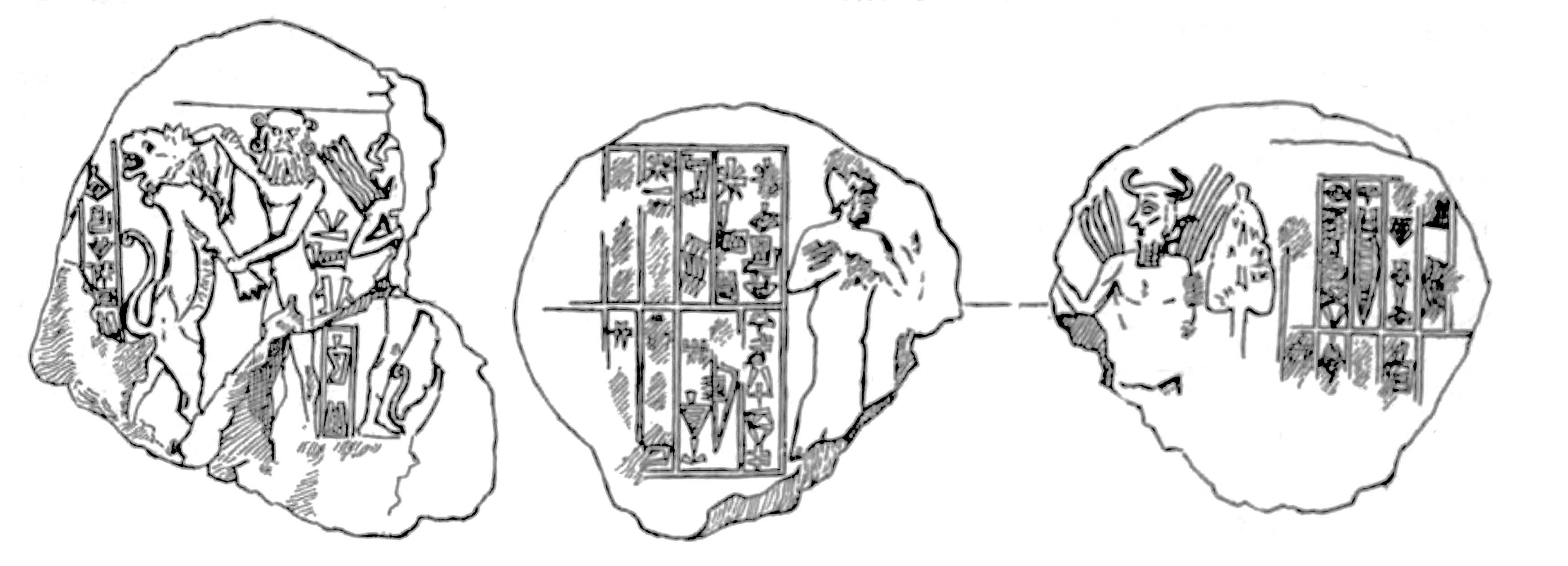

- Seals**: Several cylinder seals bearing Naram-Sin's name or depicting scenes from his era are known, offering glimpses into Akkadian artistic conventions and administrative practices.

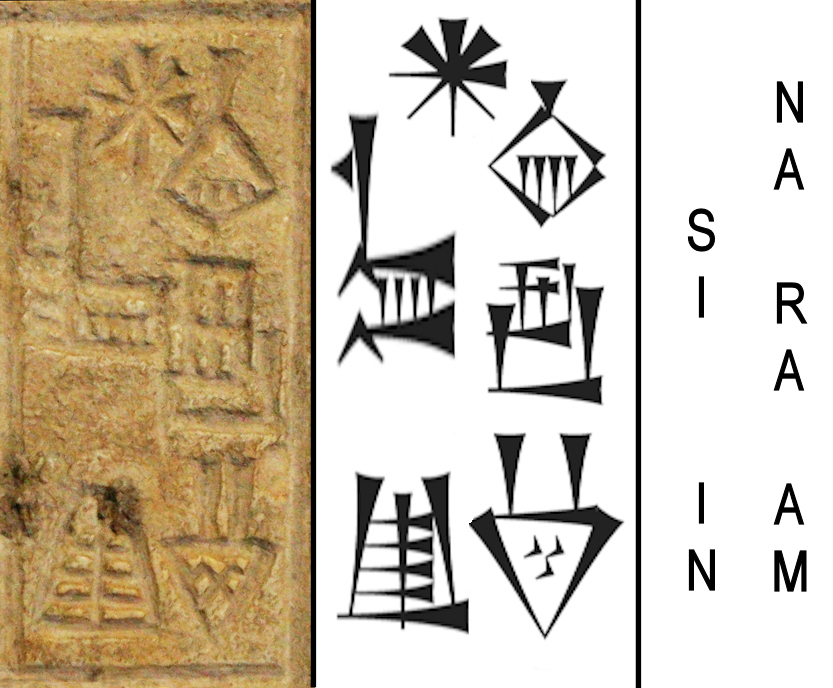

- Vases and Bowls**: An alabaster vase (Louvre Museum AO 74) is inscribed with "Naram-Sin, King of the four regions" (𒀭𒈾𒊏𒄠𒀭𒂗𒍪 𒈗 𒆠𒅁𒊏𒁴 𒅈𒁀𒅎DNa-ra-am DSîn lugal ki-ibratim arbaimAkkadian), emphasizing his key royal title. A fragment of a stone bowl from Ur (British Museum BM 118553) features an inscription of Naram-Sin, with a second inscription by Shulgi (upside down), indicating later reuse.

- Mace Heads**: A mace head (Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago) bears the inscription "Naram-Sin, king of the four quarters, dedicated (this mace) to the goddess Ishtar at Nippur", illustrating his religious piety and patronage.

- Statues and Fragments**: A bronze head, often attributed to Sargon of Akkad, is now believed by some scholars to depict Naram-Sin due to stylistic considerations. Fragments of diorite statue bases and a statue fragment (Louvre Museum Sb 53) bearing Naram-Sin's name further attest to the creation of royal effigies during his reign. A terracotta stamp for mudbricks also carries his cuneiform name.

- Inscribed Fragments**: Various other inscribed fragments, including a copy of an inscription (Louvre Museum AO 5475) and a piece of gold foil, feature his name in cuneiform. The cuneiform for "Naram-Sin" often includes the silent honorific star symbol ({{lang|akk|𒀭|}}) for "Divine" and the special writing "EN-ZU" ({{lang|akk|𒂗𒍪|}}) for the moon god Sîn.

- Rock Reliefs**: A rock relief image at Darband-i-Gawr was initially thought to depict Naram-Sin, although its attribution has since been disputed by scholars.

6. See also

- Akkadian Empire

- Sargon of Akkad

- Shar-Kali-Sharri

- Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

- Sumerian King List

- History of Mesopotamia

- Bassetki Statue

- The Dark Pictures Anthology: House of Ashes

- List of kings of Akkad

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties