1. Early Life and Education

Maurice Bishop's formative years were marked by a blend of Caribbean and European influences, shaping his early political consciousness and dedication to social justice. His academic journey and early activism laid the groundwork for his revolutionary career.

1.1. Birth and Childhood

Maurice Rupert Bishop was born on 29 May 1944 on the island of Aruba, which was then a colony of the Netherlands, part of the Territory of Curaçao. His parents, Rupert and Alimenta Bishop, hailed from the northeast of Grenada, where Rupert had earned a meager five British pence per day. Seeking better financial prospects, Rupert and Alimenta moved to Aruba in the late 1930s so that Rupert could work in an oil refinery.

Until the age of six, Maurice was raised in Aruba alongside his two older sisters, Ann and Maureen. In 1950, his father brought the family back to Grenada, where he established a small retail shop in the capital, St. George's. Maurice initially attended the Wesleyan elementary school, but after a year, he transferred to the Roman Catholic St. George Primary and High School. Already quite tall at nine years old, he was often teased for looking much older than his age. As an only son, Maurice faced considerable pressure from his father, Rupert, who demanded perfect grades, insisting on 100% rather than 95%. His mother, despite the family owning a car, expected him to walk to school like other children.

1.2. Education and Early Activism

Bishop's educational path, both in Grenada and later in England, played a crucial role in the development of his political ideology and his commitment to activism.

1.2.1. Education in Grenada

For his secondary education, Bishop was awarded one of only four government scholarships to study at the Roman Catholic Presentation Brothers' College. During his time there, he demonstrated exceptional leadership and academic abilities, being elected president of the Student Council, the Discussion Club, and the History Study Group. He also served as the editor of the school newspaper, Student Voice, and actively participated in sports. Bishop recounted his strong interest in politics, history, and sociology during these years. He formed connections with students from the Anglican Grenada Boys' Secondary School, a rival institution. He was a fervent supporter of the West Indies Federation, established in 1958, and embraced the ideas of Caribbean nationalism. The 1959 Cuban Revolution deeply captivated him, with Bishop recalling that "it did not matter what we heard on the radio or read in the colonial press. For us, it comes down to the courage and legendary heroism of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara. Nothing could overshadow this aspect of the Cuban Revolution."

During these years, Bishop and his peers delved into the works of influential thinkers like Julius Nyerere and Frantz Fanon. Shortly before his graduation in early 1962, Bishop and Bernard Coard, a youth leader from Grenada Boys' Secondary School, co-founded the Grenada Assembly of Youth Fighting for Truth. This organization aimed to foster political awareness among the island's youth through vibrant discussions on pressing issues. Members convened on Fridays in St. George's main square, organizing open political debates among the populace. Bishop's charisma and exceptional oratorical skills, including his clever use of humor in arguments, were widely acknowledged by both allies and adversaries. In 1962, Bishop graduated with the Principal's Gold Medal for his "outstanding academic and overall ability."

1.2.2. Studies and Activism in England

The activities of the Grenada Assembly concluded the following year, as Bishop and other leaders departed for universities in Europe and the United States. In December 1963, the 19-year-old Bishop arrived in England to pursue legal studies at the University of London, enrolling at Gray's Inn where he earned a Bachelor of Law degree in 1966. Meanwhile, Coard traveled to the U.S. to study economics at Brandeis University. While in London, Bishop often took on jobs as a postman or vegetable packer to support himself. From 1963 to 1966, he served as president of the Students Association of Holborn College, and in 1967, he led the association of students of the Royal College.

During his studies, Bishop delved into Grenadian history, focusing on anti-British speeches and the life of slave revolt leader Julien Fédon, who spearheaded the 1795 uprising. In 1964, he participated in the UK's West Indian Standing Conference (WISC) and the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD). His political development was further influenced by visits to socialist countries such as Czechoslovakia and the German Democratic Republic. During this period, he deeply studied the works of prominent Marxist theorists including Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao Zedong. Bishop was particularly impressed by Julius Nyerere's Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism (published in 1968) and the Arusha Declaration of 1967.

From 1967 to 1969, Bishop worked on his thesis, "Constitutional Development of Grenada," but left it unfinished due to disagreements with his supervisor regarding the assessment of the 1951 disturbances and general strike in Grenada. In 1969, he received his law degree and became a co-founder of the Legal Aid Office of the West Indies community in London's Notting Hill Gate. This was volunteer work, with his primary income coming from his job as a surtax examiner in the civil service. During his time in England, Bishop maintained correspondence with Grenadian friends and devised a two-year action plan for his return, which involved temporarily stepping away from his legal duties to help establish an organization capable of assuming power on the island.

2. Formation of Political Ideology and Early Career

Upon his return to Grenada, Maurice Bishop immediately engaged in political organizing, leading to the establishment of his influential political party, the New Jewel Movement, and a series of confrontations with the then-ruling government.

2.1. Return to Grenada and Early Activities

Returning to Grenada in December 1970, Bishop quickly immersed himself in social activism. He provided legal defense for striking nurses at St. George's General Hospital, who were seeking to improve conditions for their patients. His involvement led to his arrest, along with 30 other strike supporters, but all were acquitted after a seven-month trial. In 1972, Bishop played a key role in organizing a conference in Martinique that focused on strategizing actions for liberation movements across the region. The philosophy of Julius Nyerere and his vision of Tanzanian socialism served as guiding principles for the Movement for Assemblies of the People (MAP), which Bishop helped establish after the 1972 elections. Bishop and co-founders Kenrick Radix and Jacqueline Creft were particularly keen on steering MAP towards the creation of popular institutions rooted in local villages, aiming to facilitate broad public participation in the country's affairs.

2.2. Founding and Development of the New Jewel Movement

In January 1973, MAP merged with the Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education and Liberation (JEWEL) and the Organization for Revolutionary Education and Liberation (OREL) to form the New Jewel Movement (NJM). Maurice Bishop and Unison Whiteman, the founder of JEWEL, were elected as the NJM's Joint Coordinating Secretaries. The NJM, identified as a Marxist-Leninist party, aimed to prioritize socio-economic development, education, and black liberation, setting a clear ideological path for the party's future actions.

2.3. Confrontations with the Gairy Government

The New Jewel Movement, under Bishop's leadership, soon found itself in direct conflict with the government of Prime Minister Eric Gairy, characterized by a series of violent incidents.

On 18 November 1973, an event that became known as "Bloody Sunday" occurred. Bishop and other NJM leaders were traveling in two cars from St. George's to Grenville for a meeting with local businessmen when police officers, led by Assistant Chief Constable Innocent Belmar, intercepted Bishop's motorcade. Nine individuals, including Bishop, were captured, arrested, and severely beaten "almost to the point of death" by Belmar's police aides and the paramilitary Mongoose Gang. While imprisoned, the arrested men shaved their beards, revealing Bishop's broken jaw.

On 21 January 1974, Bishop participated in a mass demonstration against Prime Minister Gairy. As Bishop's group returned to Otway House, they were attacked with stones and bottles by Gairy's security forces, who also deployed tear gas. During this chaotic scene, Maurice's father, Rupert Bishop, was leading several women and children away from the danger when he was tragically shot in the back and killed at the door of Otway House. The perpetrators were members of the Mongoose Gang, who operated under Gairy's orders and conducted "campaigns of terror... against the New JEWEL Movement and against the Bishop family in particular." This day became known in Grenada as "Bloody Monday." Following this traumatizing event, Bishop acknowledged that the NJM was "unable to lead the working class" due to the party's limited influence within city workers' unions or among rural populations loyal to Gairy. In response, Bishop and his colleagues devised a new strategy, shifting their focus from propaganda and anti-government demonstrations towards the systematic organization of party groups and cells.

On 6 February 1974, the day before Grenada was officially proclaimed an independent state, Bishop was arrested on charges of plotting an armed anti-government conspiracy. He was taken to Fort George prison, with police claiming to have found weapons, ammunition, equipment, uniforms, a plan to assassinate Eric Gairy in a nightclub, and a scheme for establishing guerrilla camps during a search of his house. Two days later, Bishop was released on a 125 USD bail and briefly fled to North America, visiting Guyana on 29 March 1974 to participate in a meeting of the Regional Steering Committee of the Pan-African Congress. He also continued his law practice, notably defending Desmond "Ras Kabinda" Trotter and Roy Mason in October 1974, who were accused of murdering an American tourist.

2.4. Leader of the Opposition

In 1976, Maurice Bishop was elected to represent St. George's South-East in the Grenadian Parliament. From 1976 to 1979, he held the significant position of Leader of the Opposition in the House of Representatives of Grenada. In this role, he consistently challenged the government of Prime Minister Gairy and his Grenada United Labour Party (GULP), which critics asserted maintained power through threats, intimidation, and fraudulent elections, particularly the 1976 Grenadian general election. In May 1977, Bishop, accompanied by Unison Whiteman, made his first visit to Cuba, traveling as guests of the Cuban Institute of Friendship with People (ICAP), further solidifying the connections that would later become central to his government's foreign policy.

3. Premiership of the People's Revolutionary Government

Maurice Bishop's leadership as Prime Minister saw the implementation of significant domestic and foreign policies, aiming to transform Grenadian society according to his socialist ideals.

3.1. 1979 Revolution and Assumption of Power

In 1979, Bishop's party orchestrated a revolutionary coup that successfully deposed Eric Gairy, who was out of the country addressing the United Nations at the time. Following the overthrow of Gairy's government, Maurice Bishop immediately declared himself Prime Minister of Grenada and suspended the existing constitution. His ascent to power was popular and widely applauded by many Grenadians and international observers, as Gairy's rule had been characterized by increasing corruption and authoritarianism, leading to high expectations for the new People's Revolutionary Government (PRG).

3.2. Domestic Policies and Achievements

After assuming power, Bishop established a strong partnership with Cuba, which became a significant ally for his government. He initiated numerous projects in Grenada, most notably the construction of a new international airport on the island's southern tip, later renamed Maurice Bishop International Airport in his memory in May 2009. While financing and labor for the airport's construction came primarily from Cuba, much of its infrastructure was designed by European and North American consultants. This project, however, drew criticism from the United States, with President Ronald Reagan accusing Grenada of intending to use the airport's long airstrip as a waypoint for Soviet military aircraft.

Among Bishop's core principles were the advancement of workers' rights, women's rights, and a firm stance against racism and apartheid. Under his leadership, the National Women's Organization was formed, actively participating in policy decisions alongside other social groups. Women were granted equal pay and paid maternity leave, and sex discrimination was outlawed. The government also established vital organizations dedicated to education, such as the Centre for Popular Education, health care, and youth affairs, including the National Youth Organization. These reforms aimed to address social inequalities and uplift vulnerable populations. Significant achievements under Bishop's government included the introduction of free public healthcare, a substantial decrease in illiteracy rates from 35% to 5%, and a notable reduction in unemployment from 50% to 14%.

The People's Revolutionary Army (PRA) was also established during Bishop's administration. Critics contended that the army constituted a waste of resources and lodged complaints that the PRA was utilized as a tool for human rights abuses, such as the detention of political dissidents.

3.3. Economic Policies

The People's Revolutionary Government under Bishop implemented various economic policies, including the nationalization of industries and the introduction of collective farms. Despite these efforts, the economic reforms did not fully achieve their intended success, and the nation's economic growth largely stagnated.

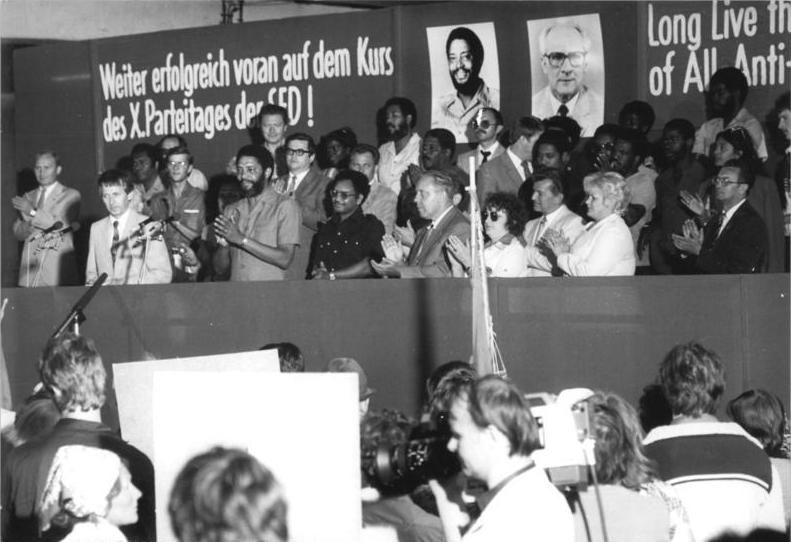

3.4. Foreign Relations

As Prime Minister, Bishop traveled extensively to cultivate international relations and to inform the world about the Grenada Revolution. He sought to forge closer ties with socialist nations. In August 1983, he delivered an impassioned speech to an enthusiastic audience at Hunter College in Brooklyn, New York. In his address, he staunchly defended Grenada's revolution, drawing parallels to the American Revolution and the Emancipation Proclamation. He also spoke critically about "the continued economic subservience of the developing world," the overthrow of Salvador Allende's government in Chile, and the brutal Contra interventions against the Sandinistas. A U.S. State Department report from that period reflected significant concern regarding Bishop and the NJM, stating that "The revolution in Grenada, it said, was in some ways even worse than the Cuban Revolution that had rocked the region a quarter of a century earlier: the vast majority of Grenadians were black, and therefore their struggle could resonate with thirty million black Americans; and the Grenadian revolutionary leaders spoke English, and so could communicate their message with ease to an American audience." Bishop's government maintained close relations with Cuba, the Soviet Union, and other countries within the Eastern Bloc.

3.5. Governance and Approach to Democracy

Bishop's government adopted a unique approach to governance, characterized by the suspension of elections and a strong emphasis on grassroots democracy. While critics pointed to the stifling of the free press and political opposition as anti-democratic measures, the PRG argued that elections were unnecessary due to the establishment of voluntary mass organizations for women, farmers, youth, workers, and militia, which were intended to ensure broad participation. Furthermore, there was a belief that traditional elections could be easily manipulated by large sums of money from foreign interests.

Bishop eloquently articulated his vision of democracy, stating:

"There are those... who believe that you cannot have a democracy unless there is a situation where every five years... people are allowed to put an 'X' next to some candidate's name, and... they return to being non-people without the right to say anything to their government, without any right to be involved in running their country.... Elections could be important, but for us the question is one of timing.... We would much rather see elections come when the economy is more stable, when the Revolution is more consolidated. When more people have in fact had benefits brought to them. When more people are literate... The right of freedom of expression can really only be relevant if people are not too hungry, or too tired to be able to express themselves. It can only be relevant if appropriate grassroots mechanisms rooted in the people exist, through which the people can effectively participate.... We talk about the human rights that the majority has never been able to enjoy,... a job, to decent housing, to a good meal.... These human rights have been the human rights for a small minority over the years in the Caribbean and the time has come for the majority of the people to begin to receive those human rights for the first time."

This perspective highlights his government's focus on social and economic rights as fundamental components of true democracy, prioritizing the well-being and participation of the majority over formal electoral processes.

4. Internal Conflict and Execution

Maurice Bishop's leadership of the People's Revolutionary Government was tragically cut short by escalating internal power struggles within the party, culminating in his arrest and execution, which had profound and immediate consequences for Grenada.

4.1. Deepening Internal Tensions

By September 1983, the simmering tensions within the PRG leadership reached a critical point. A significant faction within the party, led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard, sought to alter the power structure, proposing that Bishop either step down from his role or agree to a power-sharing arrangement. Bishop considered this proposal for several weeks but ultimately rejected it, leading to a direct confrontation with the Coard faction.

4.2. Arrest and Mass Protests

In response to Bishop's rejection, the Coard faction, in conjunction with the People's Revolutionary Army (PRA), placed Bishop under house arrest on 13 October. This act sparked widespread outrage among the Grenadian populace, leading to large-scale public demonstrations demanding Bishop's release and his return to power. The protests were immense for the island's size, with as many as 30,000 people demonstrating on an island with a population of approximately 100,000 people. Even some of Bishop's own guards joined the protests, reflecting the broad support he still commanded. Despite this considerable public backing, Bishop recognized the determined resolve of the Coard faction, confiding to a journalist: "I am a dead man."

4.3. Execution and its Immediate Aftermath

On 19 October, a large crowd of protesters succeeded in freeing Bishop from his house arrest. He made his way, initially by truck and then by car, to the army headquarters at Fort Rupert (now known as Fort George), which he and his supporters managed to seize control of. In response, Coard dispatched a military force from Fort Frederick to retake Fort Rupert. Bishop and seven other individuals, including several of his cabinet ministers and close aides, were captured. A four-man PRA firing squad executed Bishop and the others by machine-gunning them in the Fort Rupert courtyard. After he was dead, a gunman slit his throat and cut off his finger to steal his ring. The bodies were then transported to a military camp on the peninsula of Calivigny and partially burned in a pit. The precise location of their remains remains unknown to this day.

Bishop's murder had immediate and far-reaching political repercussions. Partly as a direct result of his assassination, the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) along with the nations of Barbados and Jamaica formally appealed to the United States for assistance. Sir Paul Scoon, the Governor-General of Grenada, also independently made such an appeal. Within days of the executions, U.S. President Ronald Reagan launched a U.S.-led invasion aimed at overthrowing the People's Revolutionary Government. During this invasion, Coard, Hudson Austin (who had taken power as head of the Revolutionary Military Council), and other individuals involved in Bishop's murder were arrested and subsequently tried in Britain. In 1986, Coard and Austin received death sentences, which were later commuted to life imprisonment. Their sentences were further reduced in a 2007 retrial, leading to their release from prison in 2008 and 2009 respectively.

5. Personal Life

Maurice Bishop's personal life included two significant relationships and three children. In 1966, he married Angela Redhead, a nurse. They had two children together: a son named John, born in 1967, and a daughter named Nadia, born in 1969. In 1981, while Maurice was still serving as Prime Minister, Angela emigrated to Toronto, Canada, taking both children with her.

Bishop also had a long-term relationship with Jacqueline Creft, who served as Grenada's Minister of Education in his government. With Jacqueline, he fathered a son named Vladimir Lenin Creft-Bishop, born in 1978. Tragically, Jacqueline Creft was killed alongside Maurice Bishop by the firing squad at Fort Rupert on 19 October 1983. After the deaths of his parents, Vladimir joined his half-siblings in Canada, but he too met a tragic end, being stabbed to death in a Toronto nightclub at the age of 16 in 1994.

6. Legacy and Reception

Maurice Bishop's leadership continues to be a subject of varied historical assessment, and his influence is commemorated in several ways in Grenada.

6.1. Historical Evaluation

The historical evaluation of Maurice Bishop and his People's Revolutionary Government presents a complex picture. His supporters commend his profound dedication to social equity, highlighting the significant advancements made under his leadership in areas such as public healthcare, education, and women's rights, which profoundly benefited the previously marginalized majority. The dramatic drops in illiteracy and unemployment rates are frequently cited as testaments to the positive impact of his policies on the quality of life for ordinary Grenadians. His commitment to anti-racism and anti-apartheid movements also garners praise.

However, critics and some historians also point to the controversial aspects of his governance. The suspension of elections, the stifling of the free press, and the suppression of political opposition are seen as significant departures from conventional democratic norms. While Bishop articulated a vision of "grassroots democracy" and argued that traditional elections could be manipulated by foreign interests, these actions are frequently criticized as moves towards an authoritarian single-party state. The allegations of human rights abuses, particularly the detention of political dissidents by the People's Revolutionary Army (PRA), also weigh heavily in historical assessments. Furthermore, while social reforms were impactful, the economic policies, including nationalization and collective farms, are noted as having struggled, with economic growth stagnating during his premiership.

Ultimately, Bishop's legacy is viewed through a lens that acknowledges his revolutionary zeal and genuine efforts to improve the lives of Grenadians, while also critically examining the authoritarian tendencies and internal conflicts that led to his downfall and the tragic end of the Grenada Revolution.

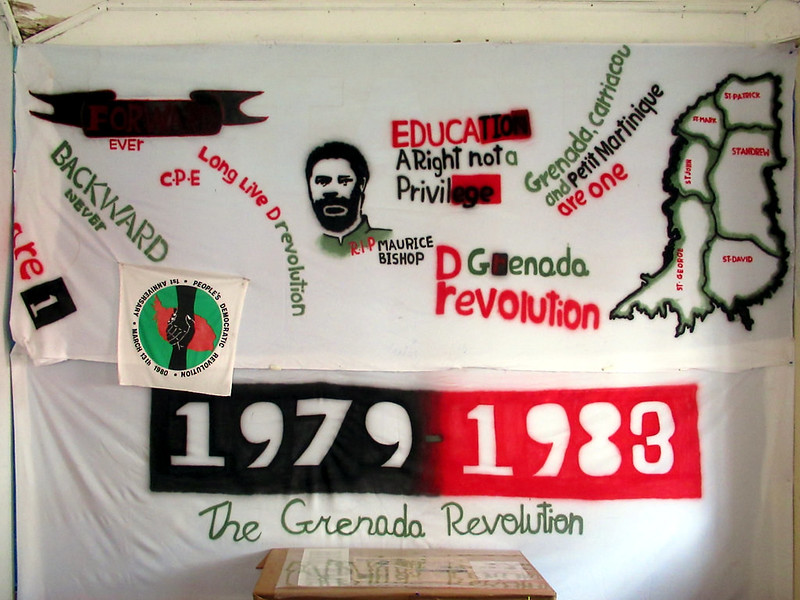

6.2. Memorials and Influence

Maurice Bishop's lasting impact is recognized through various memorials and his continued influence on Grenadian and Caribbean political discourse. On 29 May 2009, Grenada's international airport, formerly known as Point Salines International Airport, was officially renamed Maurice Bishop International Airport in his honor. Speaking at the renaming ceremony, Ralph Gonsalves, the Prime Minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, remarked, "This belated honour to an outstanding Caribbean son will bring closure to a chapter of denial in Grenada's history." This renaming signified a broader acceptance and acknowledgment of Bishop's role and contributions within Grenada. Additionally, a banner commemorating the Grenada Revolution is displayed at the Grenada National Museum, serving as a tangible reminder of the era and Bishop's central role in it. Bishop's ideas, particularly his emphasis on social justice, self-determination, and a broader definition of human rights, continue to resonate with those advocating for similar causes in the Caribbean and beyond.