1. Early Life and Background

Mary Jane Seacole was born Mary Jane Grant on 23 November 1805 in Kingston, Jamaica, then part of the Colony of Jamaica. Her father, James Grant, was a Scottish Lieutenant in the British Army. Her mother, known as Mrs. Grant or "The Doctress," was a skilled healer who utilized traditional Caribbean and African herbal medicines and ran Blundell Hall, a boarding house at 7 East Street in Kingston. The term 'Creole' was commonly used to refer to individuals of mixed European and African or Indigenous American ancestry, and Seacole proudly identified as such, stating in her autobiography, "I am a Creole, and have good Scots blood coursing through my veins. My father was a soldier of an old Scottish family." She also expressed pride in her Black ancestry, writing, "I have a few shades of deeper brown upon my skin which shows me related - and I am proud of the relationship - to those poor mortals whom you once held enslaved, and whose bodies America still owns."

Growing up in Blundell Hall, which also served as a convalescent home for military and naval staff recovering from illnesses like cholera and yellow fever, Seacole acquired her foundational nursing skills. She learned traditional West African remedies and hygienic practices from her mother, who, like other Jamaican doctresses of the 18th and early 19th centuries, possessed a vast knowledge of tropical diseases and general practitioner skills. These doctresses, including Cubah Cornwallis, Sarah Adams, and Grace Donne, practiced hygiene decades before it became a key reform in modern nursing. Seacole's autobiography recounts her early experiments in medicine on dolls and pets before assisting her mother with human patients. Her family's close ties with the army allowed her to observe military doctors, combining their knowledge with her mother's traditional remedies. She notably boasted of never losing a mother or child in neonatal care, attributing this success to her traditional West African herbal remedies and hygienic practices.

Seacole spent some years in the household of an elderly woman she called her "kind patroness," receiving a good education before returning to her mother. As the educated daughter of a Scottish officer and a free Black businesswoman, she held a high position in Jamaican society. Around 1821, Seacole visited London for a year, staying with her merchant relatives, the Henriques family. She observed racial taunting directed at a darker-skinned West Indian companion, though she herself was described as "only a little brown" or "nearly white" by some biographers. She returned to London about a year later to sell West Indian pickles and preserves. Her subsequent travels were notably independent, undertaken without a chaperone or sponsor, which was unusual for women of her era who had limited rights.

2. Caribbean and Central American Activities

Upon returning to Jamaica, Mary Seacole cared for her "old indulgent patroness" during an illness before settling back into the family home at Blundell Hall after her patroness's death. She worked alongside her mother, occasionally providing nursing assistance at the British Army hospital at Up-Park Camp. Her travels extended across the Caribbean, including visits to the British colony of New Providence in the Bahamas, the Spanish colony of Cuba, and the new Republic of Haiti. While she documented these journeys, she notably omitted mention of significant contemporary events such as the 1831 Christmas Rebellion in Jamaica or the abolition of slavery in 1833 and "apprenticeship" in 1838.

On 10 November 1836, she married Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole in Kingston. Edwin, a merchant, reportedly had a poor constitution. Family legend, though unsubstantiated by historical records, suggested Edwin was an illegitimate son of Lord Nelson and Emma Hamilton, adopted by a local "surgeon, apothecary and man midwife." The couple moved to Black River and opened a provisions store, which ultimately failed. They returned to Blundell Hall in the early 1840s.

Between 1843 and 1844, Seacole endured a series of personal tragedies. Blundell Hall was largely destroyed in a fire in Kingston on 29 August 1843, though it was rebuilt as New Blundell Hall, which she described as "better than before." Her husband died in October 1844, followed shortly by her mother. After a period of profound grief, Seacole resolved to "turn a bold front to fortune" and took over the management of her mother's hotel. She attributed her rapid recovery from grief to her "hot Creole blood," believing it allowed her to blunt the "sharp edge of [her] grief" more quickly than Europeans. She immersed herself in work, declining numerous marriage proposals.

Seacole became well-known to European military visitors who frequently stayed at Blundell Hall. In 1850, she provided nursing care during a severe cholera epidemic that claimed the lives of some 32,000 Jamaicans. Her boarding house was filled with sufferers, and she witnessed many deaths.

In 1850, Seacole's half-brother Edward moved to Cruces, Panama, then part of the Republic of New Granada. He established the Independent Hotel to accommodate the influx of travelers crossing between the eastern and western coasts of the United States due to the 1849 California Gold Rush. Cruces, located about 45 mile up the Chagres River, was the limit of river navigability during the rainy season. Travelers would journey 20 mile by donkey from Panama City to Cruces, then 45 mile downriver to the Atlantic at Chagres, or vice versa. Most of these settlements are now submerged by Gatun Lake, part of the Panama Canal.

Seacole visited her brother in Cruces in 1851. Shortly after her arrival, the town was struck by a cholera outbreak. Seacole's prompt and successful treatment of the first victim established her reputation, leading to a continuous stream of patients as the infection spread. She treated the wealthy for a fee and the poor for free. While many succumbed to the disease, Seacole's treatments, which included mustard rubs, poultices, calomel, sugars of lead, and rehydration with water boiled with cinnamon, were believed to have moderate success. She faced little competition, with the only other treatments coming from an inexperienced doctor sent by the Panamanian government and the Catholic Church. She performed an autopsy on an orphan child she had cared for, gaining "decidedly useful" new knowledge. Seacole herself contracted cholera but recovered after several weeks of rest, noting the sympathy shown by the residents of Cruces towards their "yellow doctress." Cholera returned in July 1852, affecting a military party led by Ulysses S. Grant, where a third of his 120 men died.

Despite the challenges of disease and climate, Panama remained a favored route. Seacole seized the business opportunity, opening the British Hotel, which functioned as a restaurant rather than a lodging establishment. She described it as a "tumble down hut" with two rooms, quickly adding barber services. As the wet season ended in early 1852, Seacole moved her business to Gorgona. She recounted an incident where a white American at a leaving dinner wished that "God bless the best yaller woman he ever made" and hoped she could be "bleached" to be "acceptable in any company." Seacole firmly replied that she did not "appreciate your friend's kind wishes with respect to my complexion. If it had been as dark as any nigger's, I should have been just as happy and just as useful, and as much respected by those whose respect I value." She declined the "bleaching" offer and drank "to you and the general reformation of American manners." She also noted the positions of responsibility held by escaped African-American slaves in Panama, including in the priesthood, army, and public offices, remarking on how "freedom and equality elevate men." She also observed an antipathy between Panamanians and Americans, partly attributing it to the former having been slaves of the latter.

In Gorgona, Seacole briefly operated a females-only hotel. In late 1852, she returned to Jamaica, encountering racial discrimination when attempting to book passage on an American ship, forcing her to wait for a British vessel. Soon after arriving home in 1853, Jamaican medical authorities requested her assistance in nursing victims of a severe yellow fever outbreak. Despite her best efforts, she found she could do little due to the epidemic's severity, with her own boarding house filled with sufferers. In Cuba, she was fondly remembered by those she nursed back to health, earning the moniker "the Yellow Woman from Jamaica with the cholera medicine."

Seacole returned to Panama in early 1854 to finalize her business affairs, then moved to the New Granada Mining Gold Company establishment at Fort Bowen Mine, some 70 mile away near Escribanos. She had read newspaper reports of the outbreak of war against Russia before leaving Jamaica, and news of the escalating Crimean War reached her in Panama. She resolved to travel to England to volunteer as a nurse, bringing her herbal healing skills to experience the "pomp, pride and circumstance of glorious war." A significant part of her motivation was her personal connection to some of the soldiers deployed there, having cared for and nursed men from the 97th and 48th regiments who were being shipped back to England for the Crimean Peninsula fighting.

3. Crimean War

The Crimean War, lasting from October 1853 to 1 April 1856, involved the Russian Empire against an alliance of the United Kingdom, France, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire. The conflict primarily unfolded on the Crimean Peninsula in the Black Sea and Turkey. Thousands of troops from all participating nations were deployed, and disease, particularly cholera, quickly became rampant, claiming more lives than battle. Hospitals were poorly staffed, unsanitary, and overcrowded. In Britain, a critical letter in The Times on 14 October 1854 prompted Sidney Herbert, the Secretary of State for War, to approach Florence Nightingale to organize a contingent of nurses. Nightingale departed for Turkey on 21 October.

Seacole traveled from Navy Bay in Panama to England, initially to manage her gold-mining investments. She then sought to join the second contingent of nurses bound for Crimea. She applied to the War Office and other government departments, presenting "ample testimony" of her nursing experience, though officially only one testimonial from a former medical officer was cited. In her autobiography, she expressed understanding of the authorities' initial skepticism towards a "motherly yellow woman" offering to nurse soldiers, noting that in Jamaica, where her skills were known, the response would have been different. She questioned whether racial prejudice played a role in her rejections, writing, "Was it possible that American prejudices against colour had some root here? Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?" An attempt to join Nightingale's contingent was also rebuffed, with Seacole noting that she "read in her face the fact, that had there been a vacancy, I should not have been chosen to fill it." She also approached Elizabeth Herbert, the Secretary-at-War's wife, who confirmed that the full complement of nurses had been secured.

Undeterred, Seacole resolved to travel to Crimea using her own resources and establish the British Hotel. Business cards were printed announcing her intention to open an establishment near Balaclava, offering "a mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers." Shortly thereafter, her Caribbean acquaintance, Thomas Day, unexpectedly arrived in London, and they formed a partnership. They gathered supplies, and Seacole embarked on the Dutch screw-steamer Hollander on 27 January 1855, bound for Constantinople. During a stop in Malta, she met a doctor who had recently left Scutari, who provided her with a letter of introduction to Nightingale.

Seacole visited Nightingale at the Barrack Hospital in Scutari, requesting a bed for the night. She recounted a friendly meeting, with Nightingale asking if she needed assistance. Seacole explained her intention to travel to Balaclava to join her business partner. A bed was provided, and breakfast was sent to her in the morning. A footnote in her memoir states that Seacole later "saw much of Miss Nightingale at Balaclava," though no further specific meetings are detailed in the text. However, Nightingale's private correspondence, such as a letter from 5 August 1870, indicated her reluctance for her nurses to associate with Seacole, alleging that Seacole's establishment fostered "much drunkenness and improper conduct."

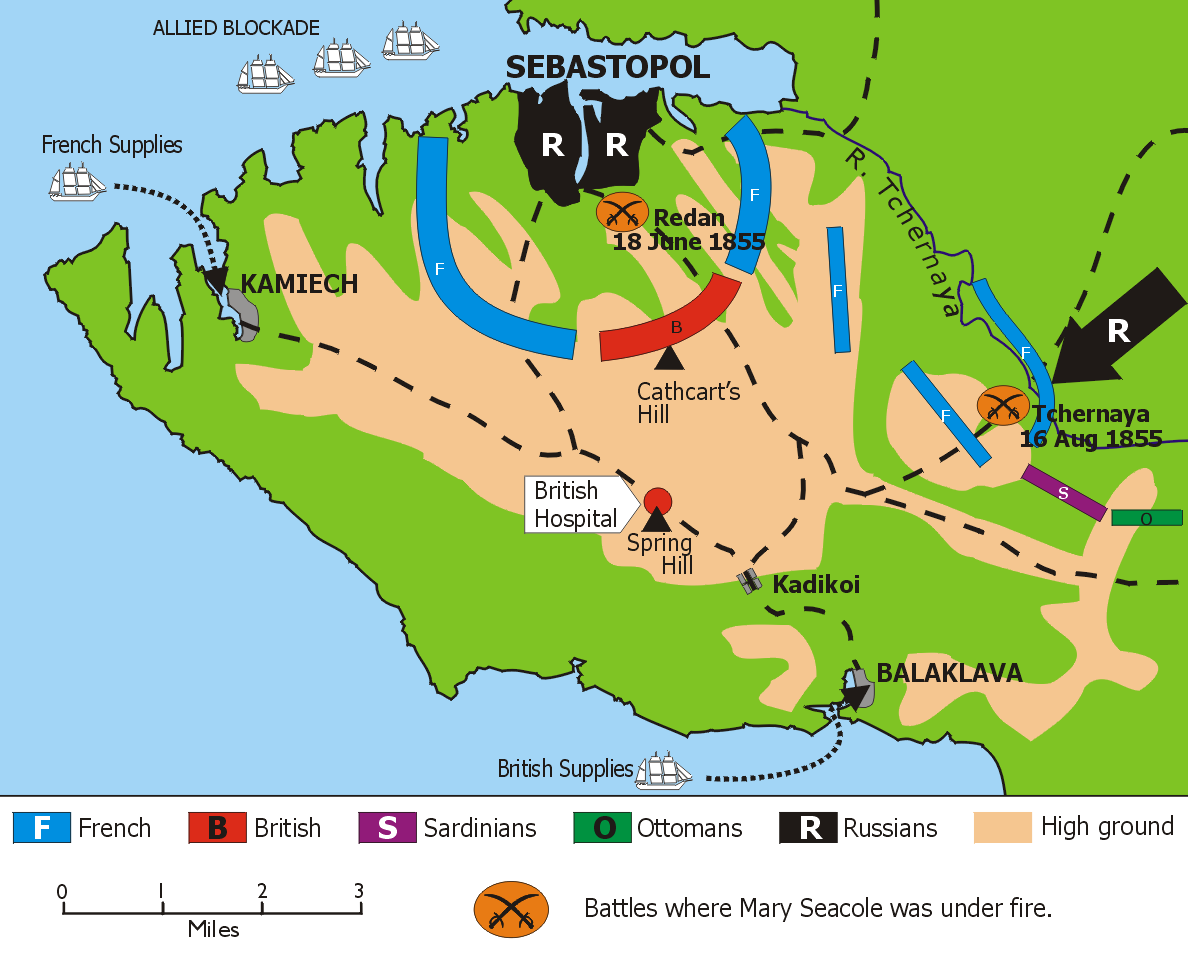

After transferring her provisions to transport ships, Seacole embarked on the four-day voyage to the British bridgehead in Crimea at Balaclava. Lacking proper building materials, she collected abandoned metal and wood to construct her hotel. She found a site at Spring Hill, near Kadikoi, approximately 3.5 mile along the main British supply road from Balaclava to the British camp near Sevastopol, and within a mile of the British headquarters.

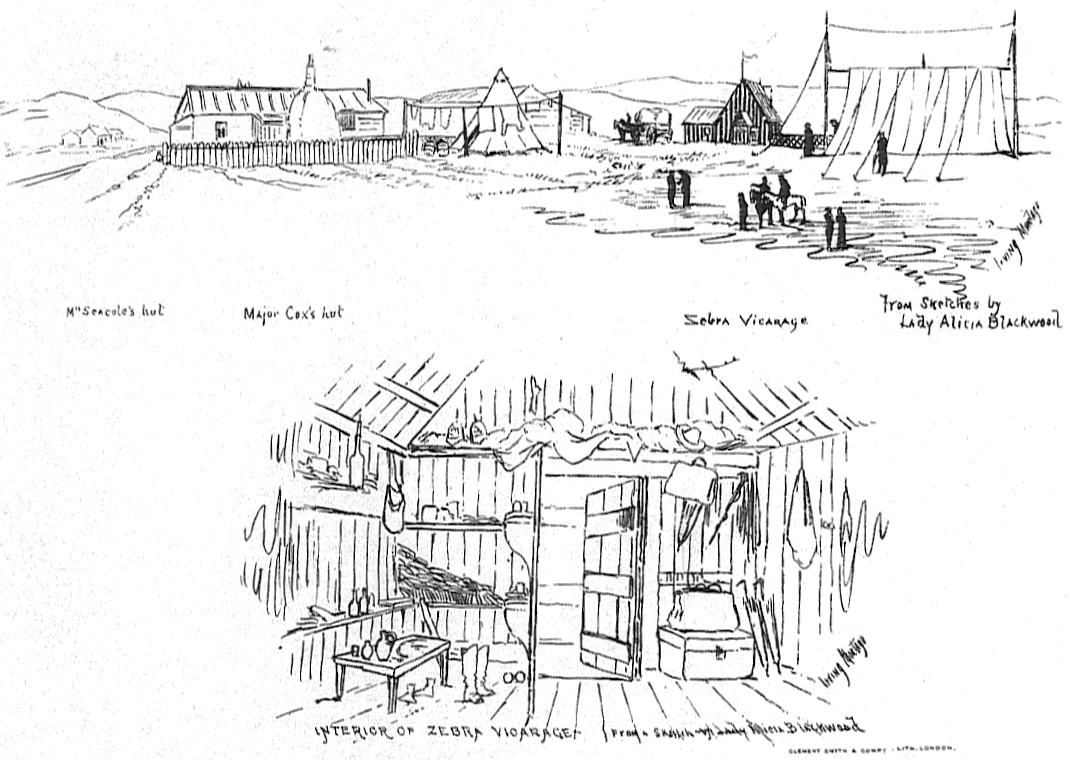

The British Hotel was constructed from salvaged driftwood, packing cases, iron sheets, and architectural items like glass doors and window-frames from the village of Kamara, using hired local labor. It opened in March 1855. An early visitor was Alexis Soyer, a renowned French chef who had traveled to Crimea to improve British soldiers' diets. Soyer described Seacole as "an old dame of a jovial appearance, but a few shades darker than the white lily" and advised her to focus on food and beverage service rather than offering overnight accommodation.

The hotel was completed in July at a total cost of 800 GBP. It featured an iron building with a main room, counters, shelves, storage, an attached kitchen, two wooden sleeping huts, outhouses, and an enclosed stable-yard. Stocked with provisions from London and Constantinople, as well as local purchases, Seacole sold a wide array of goods-"from a needle to an anchor"-to army officers and sightseers. Meals, prepared by two Black cooks, were served at the hotel, which also offered outside catering. Despite constant thefts, particularly of livestock, Seacole's establishment thrived. She often did some of the cooking herself, stating, "Whenever I had a few leisure moments, I used to wash my hands, roll up my sleeves, and roll out pastry." She also "dispensed medications" when called upon. Soyer frequently visited and praised her offerings, noting that she offered him champagne on his first visit.

Seacole frequently ventured out to the troops as a sutler, selling provisions near the British camp at Kadikoi and nursing casualties from the trenches around Sevastopol or the Tchernaya valley. She became widely known to the British Army as "Mother Seacole." She made a point of wearing brightly colored, highly conspicuous clothing, often bright blue or yellow with contrasting ribbons. While attending wounded troops under fire, she dislocated her right thumb, an injury that never fully healed. William Howard Russell, the special correspondent for The Times, praised her in a dispatch on 14 September 1855, calling her a "warm and successful physician, who doctors and cures all manner of men with extraordinary success." He noted her constant presence near the battlefield to aid the wounded and that she had "earned many a poor fellow's blessing," adding that she "redeemed the name of sutler" and was "both a Miss Nightingale and a [chef]." Lady Alicia Blackwood later recalled that Seacole "...personally spared no pains and no exertion to visit the field of woe, and minister with her own hands such things as could comfort or alleviate the suffering of those around her; freely giving to such as could not pay..."

British medical officers, initially wary, soon recognized Seacole's vital role in both medical assistance and morale. One officer described her as a "celebrated person" who "out of the goodness of her heart and at her own expense, supplied hot tea to the poor sufferers [wounded men being transported to Scutari]." He noted her tireless dedication, stating, "In rain and snow, in storm and tempest, day after day she was at her self-chosen post with her stove and kettle, in any shelter she could find, brewing tea for all who wanted it, and they were many." Beyond providing tea, she often carried bags of lint, bandages, needles, and thread to tend to soldiers' wounds.

In late August 1855, Seacole was en route to Cathcart's Hill for the final assault on Sevastopol on 7 September. After the city fell, she fulfilled a bet, becoming the first British woman to enter Sevastopol. With a pass, she toured the devastated city, offering refreshments and visiting the crowded hospital filled with thousands of dead and dying Russians. Her foreign appearance led to her being stopped by French looters, but she was rescued by a passing officer. She also acquired some items from the city, including a church bell, an altar candle, and a 9.8 ft (3 m) long painting of the Madonna.

After the fall of Sevastopol, hostilities continued desultorily. Seacole and Day's business prospered during this interim period, with officers enjoying the quieter days. Seacole provided catering for theatrical performances and horse-racing events. A 14-year-old girl named Sarah, also known as Sally, joined Seacole. Soyer described her as "the Egyptian beauty, Mrs Seacole's daughter Sarah," with blue eyes and dark hair. While Florence Nightingale reportedly alleged Sarah was the illegitimate offspring of Seacole and Colonel Henry Bunbury, there is no evidence Bunbury ever met Seacole or visited Jamaica during her husband's illness. Biographer Ron Ramdin speculates that Thomas Day might have been Sarah's father, citing their unlikely meetings in Panama and England and their unusual business partnership in Crimea.

Peace talks began in Paris in early 1856, leading to friendly relations between the Allies and the Russians, with active trade across the River Tchernaya. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 30 March 1856, after which soldiers began to leave Crimea. Seacole faced a difficult financial situation, with her business full of unsaleable provisions and new goods arriving daily while creditors demanded payment. She tried to sell as much as possible before the soldiers departed but was forced to auction many expensive goods at lower-than-expected prices to Russians returning home. The Allied armies' evacuation from Balaclava was formally completed on 9 July 1856, with Seacole "conspicuous in the foreground... dressed in a plaid riding-habit." She was among the last to leave Crimea, returning to England "poorer than [she] left it." Despite her financial losses, her impact on the soldiers was invaluable, transforming their perceptions of her. The Illustrated London News noted, "Perhaps at first the authorities looked askant at the woman-volunteer; but they soon found her worth and utility; and from that time until the British army left the Crimea, Mother Seacole was a household word in the camp... In her store on Spring Hill she attended many patients, cared for many sick, and earned the good will and gratitude of hundreds."

4. Autobiography and Literary Work

In July 1857, a 200-page autobiographical account of Mary Seacole's travels, titled Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, was published by James Blackwood. This marked the first autobiography written by a Black woman in Britain. Priced at one shilling and six pence (1/6), the book's cover featured a portrait of Seacole in red, yellow, and black ink. It is speculated that she dictated the work to an editor, identified only as W.J.S., who refined her grammar and orthography.

The book dedicates a single, brief chapter to the first 39 years of her life. It then expands into six chapters detailing her experiences in Panama, followed by twelve chapters recounting her exploits in Crimea. Seacole deliberately omits the names of her parents and her precise date of birth. Within the narrative, she describes how her medical practice began by treating animals like cats and dogs, which often contracted diseases from their owners, using her homemade remedies. She also discusses her financial struggles upon returning from the Crimean War, contrasting her poverty with the wealth others in similar positions acquired. Seacole emphasizes the deep respect she earned from the soldiers during the Crimean War, who affectionately referred to her as "mother" and personally guarded her on the battlefield to ensure her safety.

A short concluding section addresses her return to England and lists prominent supporters of her fundraising efforts, including Major General Lord Rokeby, Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar, the Duke of Wellington, the Duke of Newcastle, and the war correspondent William Russell, among other distinguished military figures. In this conclusion, Seacole expresses pride and pleasure in all her career adventures during the Crimean War. The book was dedicated to Major-General Lord Rokeby, commander of the First Division. In a brief preface, The Times correspondent William Howard Russell lauded her, writing, "I have witnessed her devotion and her courage... and I trust that England will never forget one who has nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead."

The Illustrated London News reviewed the autobiography favorably, echoing the sentiments of the preface: "If singleness of heart, true charity and Christian works - of trials and sufferings, dangers and perils, encountered boldly by a helpless women on her errand of mercy in the camp and in the battlefield can excite sympathy or move curiosity, Mary Seacole will have many friends and many readers." In 2017, Robert McCrum selected it as one of the 100 best nonfiction books, describing it as "gloriously entertaining."

5. Later Life and Death

After the Crimean War, Mary Seacole returned to England in August 1856, destitute and in poor health. Her autobiography mentions visiting "yet other lands" on her return journey, which biographer Jane Robinson attributes to her financial hardship necessitating a roundabout trip. She opened a canteen with Thomas Day at Aldershot, but the venture failed due to a lack of funds. On 25 August 1856, she attended a celebratory dinner for 2,000 soldiers at Royal Surrey Gardens in Kennington, where Florence Nightingale was the chief guest. Reports in The Times and News of the World indicated that Seacole was also celebrated by the large crowds, with two "burly" sergeants protecting her from the throng. However, creditors who had supplied her firm in Crimea pursued her, forcing her to move to 1 Tavistock Street, Covent Garden, in increasingly dire financial straits. The Bankruptcy Court in Basinghall Street declared her bankrupt on 7 November 1856. Robinson speculates that her business problems may have been partly caused by her partner, Day, who was involved in horse trading and possibly operated as an unofficial bank.

Around this time, Seacole began wearing military medals. A bust by George Kelly, based on an original by Count Gleichen from around 1871, depicts her wearing four medals: the British Crimea Medal, the French Légion d'honneur, the Turkish Order of the Medjidie, and "apparently" a Sardinian award. While her obituary in the Jamaican Daily Gleaner on 9 June 1881 stated she also received a Russian medal, no formal notice of these awards exists in the London Gazette. It is believed she may have purchased miniature or "dress" medals to display her support and affection for the Army.

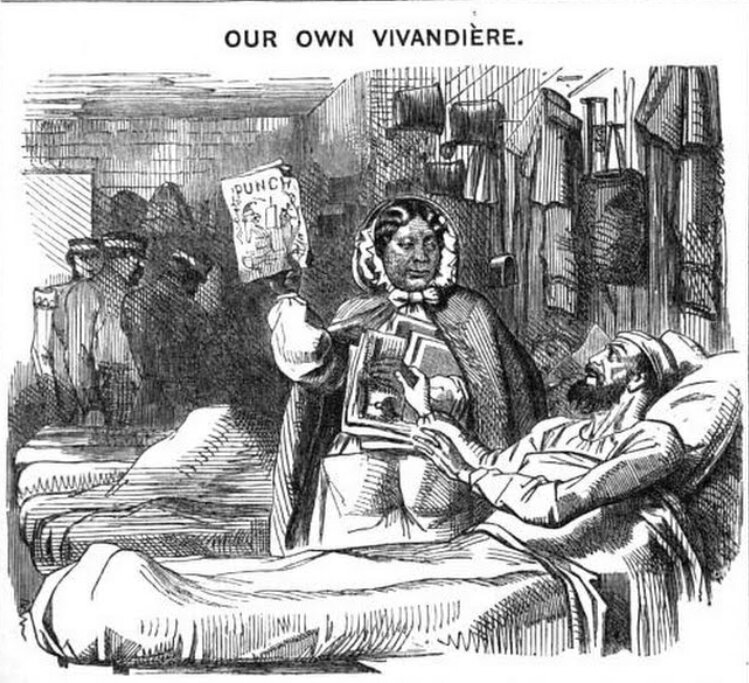

Seacole's financial plight was highlighted in the British press, leading to the establishment of a fund supported by many prominent individuals. On 30 January 1857, she and Day were discharged from bankruptcy. Day departed for the Antipodes, but Seacole's funds remained low. She moved to cheaper lodgings at 14 Soho Square in early 1857, prompting a plea for subscriptions from Punch on 2 May. However, in its 30 May edition, Punch heavily criticized her for a letter requesting donations, satirizing her as "Our Own Vivandière" and observing that she had "sunk much lower in the world, and is also in danger of rising much higher in it, than is consistent with the honour of the British army, and the generosity of the British public." Despite urging public donations, the commentary's tone was ironic.

Mark Bostridge, in researching his biography of Florence Nightingale, discovered a letter in Nightingale's sister's archive that showed Nightingale had contributed to Seacole's fund, indicating that Nightingale recognized the value of Seacole's work in Crimea at that time.

Further fundraising efforts and literary mentions kept Seacole in the public eye. In May 1857, she expressed a desire to travel to India to assist the wounded in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, but she was dissuaded by both the new Secretary of War, Lord Panmure, and her ongoing financial difficulties. Fundraising activities included the "Seacole Fund Grand Military Festival," held at the Royal Surrey Gardens from 27 to 30 July 1857. This successful event was supported by many military figures, including Major General Lord Rokeby and Lord George Paget. Over 1,000 artists performed, including 11 military bands and an orchestra conducted by Louis Antoine Jullien, attracting approximately 40,000 attendees. Despite the high entrance fees, production costs were substantial, and the Royal Surrey Gardens Company became insolvent immediately after the festival, resulting in Seacole receiving only 57 GBP, a quarter of the profits. By the time the company's financial affairs were resolved in March 1858, the Indian Mutiny had ended. In his 1859 account of his journey to the West Indies, British novelist Anthony Trollope described visiting Mrs. Seacole's sister's hotel in Kingston, noting the servants' pride and the hostess's endearing insistence on serving traditional English fare.

Seacole joined the Catholic Church around 1860 and returned to Jamaica, which was facing an economic downturn. She became a prominent figure in the country. However, by 1867, she again faced financial difficulties, prompting the revival of the Seacole fund in London. New patrons included the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Edinburgh, the Duke of Cambridge, and many other senior military officers. The fund flourished, enabling Seacole to purchase land on Duke Street in Kingston, near New Blundell Hall, where she built a bungalow as her new home and a larger property for rent.

By 1870, Seacole was back in London, residing at 40 Upper Berkeley Street, St. Marylebone. It is speculated that she returned with the intention of offering medical assistance during the Franco-Prussian War. She likely approached Sir Harry Verney, a Member of Parliament and husband of Florence Nightingale's sister, Parthenope, who was deeply involved with the British National Society for the Relief of the Sick and Wounded. It was during this period that Nightingale wrote her letter to Verney, insinuating that Seacole had maintained a "bad house" in Crimea and was responsible for "much drunkenness and improper conduct."

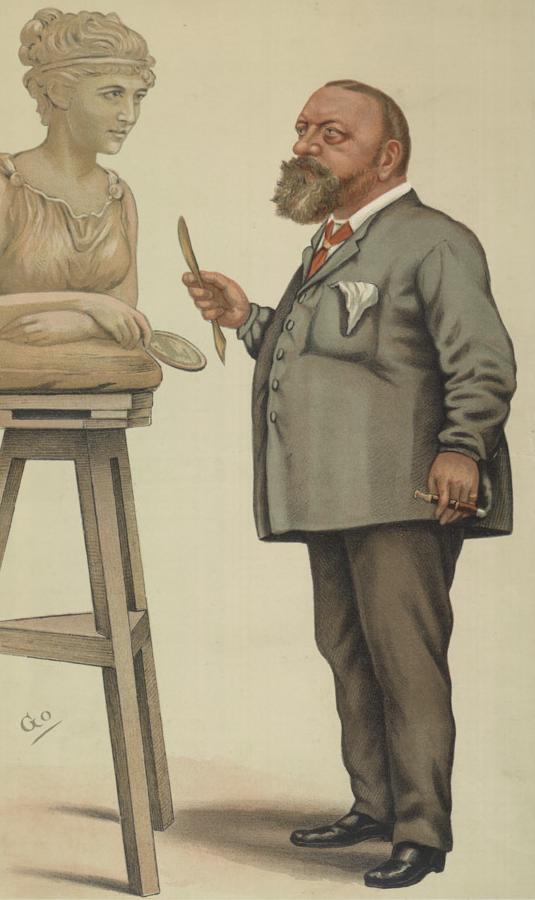

In London, Seacole entered the periphery of the royal circle. Prince Victor, a nephew of Queen Victoria and a former customer of Seacole's in Crimea, carved a marble bust of her in 1871, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1872. Seacole also became a personal masseuse to the Princess of Wales, who suffered from white leg and rheumatism.

In the census of 3 April 1881, Seacole was listed as a boarder at 3 Cambridge Street, Paddington. Mary Seacole died on 14 May 1881 at her home, 3 Cambridge Street (later renamed Kendal Street) in Paddington, London. Her cause of death was recorded as "apoplexy" (likely a stroke). She left an estate valued at over 2.50 K GBP. After several specific legacies, many of exactly 19 guineas, the primary beneficiary of her will was her sister, (Eliza) Louisa. Lord Rokeby, Colonel Hussey Fane Keane, and Count Gleichen, three trustees of her fund, each received 50 GBP. Count Gleichen also received a diamond ring, said to have been given to Seacole's late husband by Lord Nelson. A short obituary was published in The Times on 21 May 1881. She was buried in St. Mary's Catholic Cemetery, Harrow Road, Kensal Green, London.

6. Legacy and Recognition

While well-known at the end of her life, Mary Seacole's public memory in Britain rapidly faded. However, she was better remembered in Jamaica, where significant buildings were named in her honor in the 1950s. The headquarters of the Jamaican General Trained Nurses' Association was christened "Mary Seacole House" in 1954, followed swiftly by the naming of a hall of residence at the University of the West Indies in Mona, Jamaica, and a ward at Kingston Public Hospital. More than a century after her death, Seacole was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1990.

Her grave in London was rediscovered in 1973, leading to a service of reconsecration on 20 November 1973. Her gravestone was also restored by the British Commonwealth Nurses' War Memorial Fund and the Lignum Vitae Club. Despite this, she was notably absent from scholarly and popular works about the Black British presence in Britain during the 1970s. The centenary of her death was marked by a memorial service on 14 May 1981, and her grave is maintained by the Mary Seacole Memorial Association, an organization founded in 1980 by Jamaican-British Auxiliary Territorial Service corporal, Connie Mark.

By the 21st century, Seacole's prominence significantly increased. In 2005, British politician Boris Johnson reflected on learning about Seacole from his daughter's school pageant, speculating that his own education might have been "blinkered" compared to the more faithful account of heroism his children were receiving. In 2007, Seacole was introduced into the National Curriculum in England, and her life story is now taught in many primary schools alongside that of Florence Nightingale. In 2004, she was voted the greatest black Briton in an online poll conducted by the black heritage website Every Generation. A portrait identified as Seacole in 2005 was featured on one of ten first-class stamps commemorating the 150th anniversary of the National Portrait Gallery.

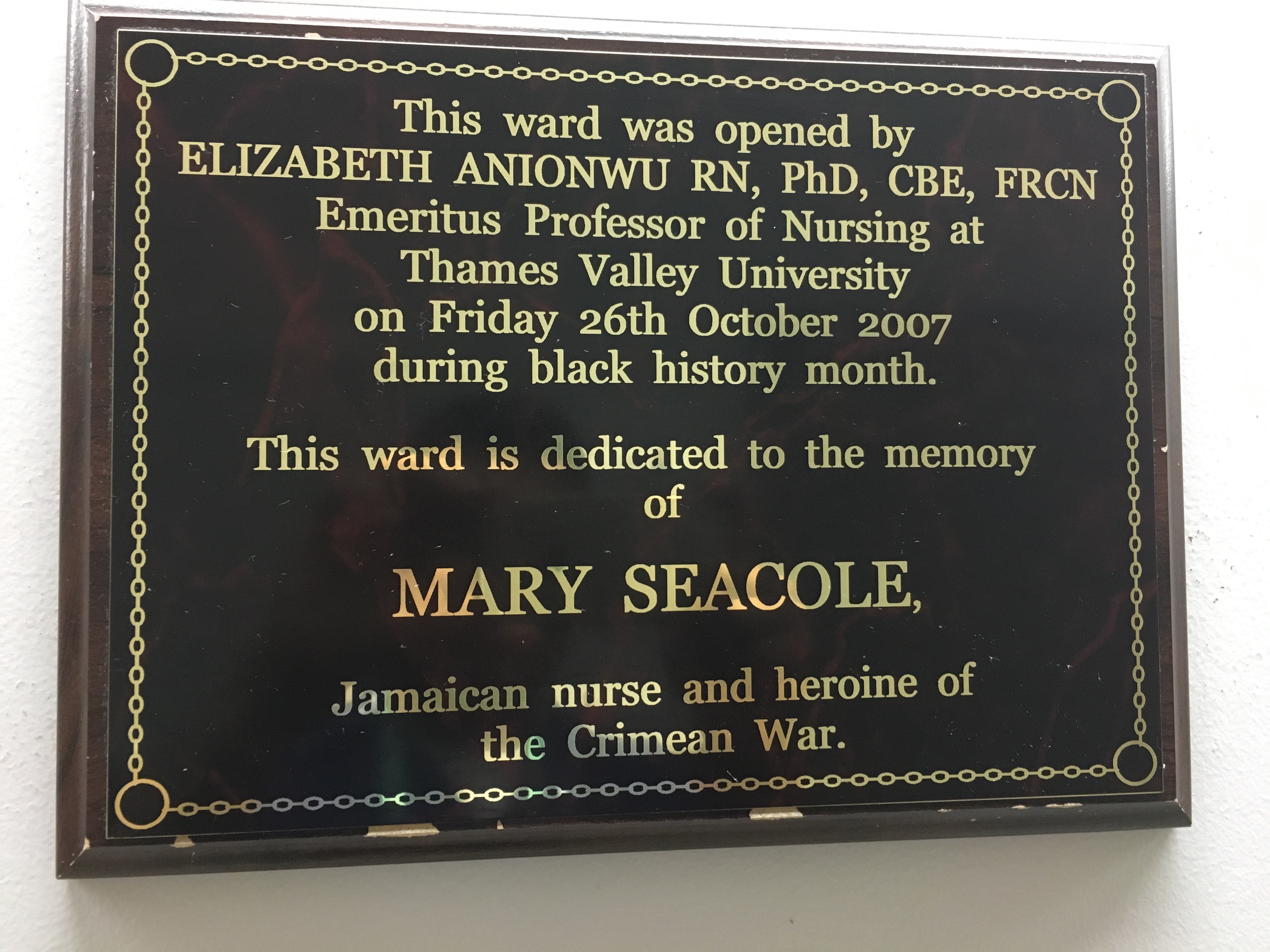

Numerous British buildings and organizations, particularly those connected with healthcare, have been named in her honor. These include the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at Thames Valley University, which established the NHS Specialist Library for Ethnicity and Health; the Mary Seacole Research Centre at De Montfort University in Leicester; a problem-based learning room at St George's, University of London; the Mary Seacole Building housing the School of Health Sciences and Social Care at Brunel University; new buildings at the University of Salford and Birmingham City University; and a part of the new headquarters of the Home Office at 2 Marsham Street. Additionally, there is a Mary Seacole ward in the Douglas Bader Centre in Roehampton, two wards named after her in Whittington Hospital in North London, and the Mary Seacole Nursing Home in Shoreditch. The Royal South Hants Hospital in Southampton named its outpatients' wing "The Mary Seacole Wing" in 2010. The NHS Seacole Centre in Surrey, opened on 4 May 2020 following a campaign led by Patrick Vernon, serves as a community hospital initially providing rehabilitation for COVID-19 patients.

An annual prize to recognize and develop leadership in nurses, midwives, and health visitors within the National Health Service was named the Seacole Award, acknowledging her achievements. The NHS Leadership Academy also developed a six-month leadership course called the Mary Seacole Programme for first-time leaders in healthcare. An exhibition celebrating the bicentenary of her birth opened at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London in March 2005, proving so popular it was extended until March 2007.

A campaign to erect a statue of Seacole in London was launched on 24 November 2003, chaired by Clive Soley, Baron Soley. The design for the sculpture by Martin Jennings was unveiled on 18 June 2009. Despite significant opposition to its placement at the entrance of St Thomas' Hospital, it was unveiled on 30 June 2016. The words written by William Howard Russell in The Times in 1857 are etched onto the statue: "I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them, and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead." The making of the Jennings statue was documented in the ITV documentary David Harewood: In the Shadow of Mary Seacole (2016), which also explored her life story.

In popular culture, a biopic of her life starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw was proposed in 2019. A short animation titled Mother Seacole was adapted from a 2005 book for her bicentenary. Seacole has been portrayed by Dominique Moore in BBC's Horrible Histories, though a sketch about her and Nightingale led to viewer complaints and a BBC Trust finding of "materially inaccurate" portrayal of racial issues. A two-dimensional sculpture of Seacole was erected in Paddington in 2013, and on 14 October 2016, Google honored her with a Google Doodle. The 2019 biodrama "Marys Seacole" by Jackie Sibblies Drury explores her life and imagines her in contemporary settings. Greg Jenner's 2020 book Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver Screen briefly discusses Seacole and draws comparisons with Florence Nightingale.

6.1. Commemoration and Remembrance

Mary Seacole has been honored in numerous ways, reflecting a growing appreciation for her pioneering life and work. In Jamaica, her memory was preserved through the naming of significant healthcare-related buildings in the 1950s, including "Mary Seacole House" for the General Trained Nurses' Association, a hall of residence at the University of the West Indies, and a ward at Kingston Public Hospital. She was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit in 1990.

In London, her grave was rediscovered in 1973, leading to a reconsecration service and restoration of her gravestone. The Mary Seacole Memorial Association, founded in 1980, continues to maintain her grave. A blue plaque was initially erected at her residence in 157 George Street, Westminster, in 1985, though it was later removed and re-erected at 14 Soho Square, where she lived in 1857. A "green plaque" was unveiled at the 157 George Street site in 2005.

Her name has been given to various modern institutions and initiatives, particularly in healthcare. These include the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at Thames Valley University, the Mary Seacole Research Centre at De Montfort University, and dedicated spaces in other universities and hospitals across the UK, such as Brunel University, the University of Salford, Birmingham City University, Whittington Hospital, and the Royal South Hants Hospital. The NHS Seacole Centre in Surrey, a community hospital, was opened in 2020.

Seacole's contributions are also recognized through awards and educational programs. The NHS offers the annual Seacole Award for leadership in nursing, and the NHS Leadership Academy developed the Mary Seacole Programme, a six-month leadership course. Her life story was integrated into the National Curriculum in England in 2007, taught alongside Florence Nightingale's. She was voted the greatest Black Briton in a 2004 online poll and featured on a first-class stamp commemorating the National Portrait Gallery's 150th anniversary.

The campaign for a statue of Seacole in London culminated in the unveiling of a sculpture by Martin Jennings at St Thomas' Hospital in 2016, bearing a tribute from William Howard Russell. Her story has also been adapted into various forms of popular culture, including proposed biopics, animated shorts, television appearances in Horrible Histories, a two-dimensional sculpture in Paddington, and a Google Doodle.

6.2. Criticism and Controversy

Mary Seacole's recognition has been met with controversy, primarily from members of the Nightingale Society, an organization founded by sociology professor Lynn McDonald in 2012 to promote Florence Nightingale's legacy. McDonald argues that Seacole has been promoted at Nightingale's expense and that support for Seacole has been used to undermine Nightingale's reputation as a pioneer in public health and nursing. Critics have opposed the siting of Seacole's statue at St Thomas' Hospital, asserting she had no connection to the institution, unlike Nightingale. Sean Lang has stated that Seacole "does not qualify as a mainstream figure in the history of nursing." A letter to The Times from the Florence Nightingale Society, signed by historians and biographers, claimed that Seacole's "battlefield excursions... took place post-battle, after selling wine and sandwiches to spectators," and that she "was a kind and generous businesswoman, but was not a frequenter of the battlefield 'under fire' or a pioneer of nursing." McDonald further argued in The Times Literary Supplement that Seacole's "tea and lemonade did not save lives, pioneer nursing or advance health care."

However, historians and commentators have countered these criticisms. Many argue that dismissing Seacole's work as merely "tea and lemonade" disregards the tradition of Jamaican "doctresses," such as Seacole's mother, Cubah Cornwallis, Sarah Adams, and Grace Donne. These practitioners, long before Nightingale, utilized herbal remedies and hygienic practices derived from West African healing traditions, often achieving greater success than European-trained doctors of the time. Social historian Jane Robinson asserts that Seacole was a "huge success," known and loved by individuals from common soldiers to the royal family. Mark Bostridge pointed out that Seacole's experience, which included preparing medicines, diagnosis, and minor surgery, "far outstripped Nightingale's." William Howard Russell, the war correspondent, highly praised Seacole's skill as a healer, writing, "A more tender or skilful hand about a wound or a broken limb could not be found among our best surgeons."

Some scholars, including the sculptor Martin Jennings and American academic Gretchen Gerzina, suggest that racial bias plays a part in the resistance to Seacole's recognition. One criticism leveled by Nightingale's supporters is that Seacole was not trained at an accredited medical institution. However, proponents argue that Jamaican women like Seacole's mother developed their nursing skills from West African healing traditions (sometimes known as obeah in Jamaica), which involved hygiene decades before Nightingale adopted it as a key reform in her 1859 book Notes on Nursing.

The debate surrounding Seacole's place in the National Curriculum also highlights these tensions. In late 2012, reports emerged that Mary Seacole was to be removed from the curriculum. Greg Jenner, historical consultant for Horrible Histories, argued against her removal, stating that while her medical achievements might have been exaggerated, her inclusion was important. Susan Sheridan contended that the proposed removal was part of a broader shift away from social history towards a focus solely on large-scale political and military history. Many commentators do not accept the view that Seacole's accomplishments were exaggerated. British social commentator Patrick Vernon has opined that claims of exaggeration often originate from an establishment seeking to suppress and conceal the contributions of Black people to British history. Helen Seaton suggested that Nightingale fit the Victorian ideal of a heroine more than Seacole, and that Seacole's ability to overcome racial prejudice makes her "a fitting role model for both blacks and non-blacks." Cathy Newman argued that proposed curriculum changes could mean that children would only learn about queens when studying women in history. In January 2013, Operation Black Vote launched a petition, supported by figures like Rev. Jesse Jackson, to keep Seacole and Olaudah Equiano in the National Curriculum. This campaign proved successful, and the Department for Education opted to retain Seacole in the curriculum on 8 February 2013.

6.3. Impact

Mary Seacole's broader influence extends beyond her direct medical contributions. Her pioneering status as a Black woman who achieved prominence in Victorian society, despite pervasive racial prejudice and social barriers, makes her an enduring symbol of resilience. Her self-funded journey to the Crimean War and the establishment of her "British Hotel" demonstrated remarkable independence and entrepreneurial spirit at a time when women, particularly women of color, had limited opportunities.

Her work on the front lines, providing comfort, food, and medical care to soldiers of all ranks and nationalities, showcased a compassionate and inclusive approach to humanitarian aid. The affectionate title "Mother Seacole" bestowed upon her by the soldiers underscores the profound personal impact she had on their lives and morale. Her autobiography, the first by a Black woman in Britain, provided a unique voice and perspective, challenging prevailing stereotypes and offering a firsthand account of her extraordinary experiences.

The posthumous recognition she has received, including national honors, the naming of institutions, and her inclusion in educational curricula, reflects a growing societal acknowledgment of her historical significance. While debates persist regarding the exact nature and scope of her nursing contributions compared to Florence Nightingale, Seacole's legacy is increasingly celebrated for her courage, her defiance of racial and gender norms, and her embodiment of a spirit of service that transcended conventional boundaries. She continues to inspire as a role model for overcoming adversity and contributing to the welfare of others.